Walkable and Sustainable City Centre Greenway Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Mechanism

2.1. Codes and Norms

2.2. Vitality and Vibrancy

2.3. Riverfront Greenways

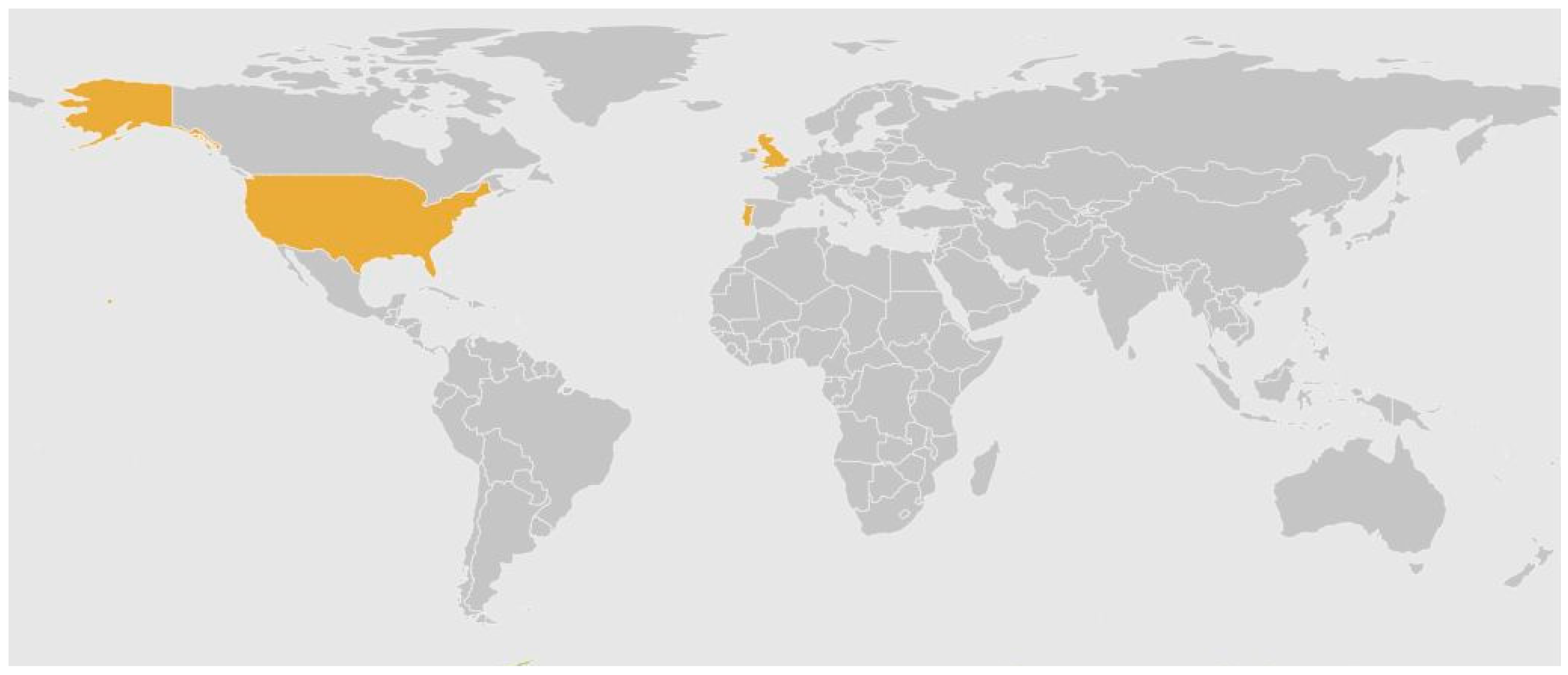

3. Materials and Methods

4. Case Studies

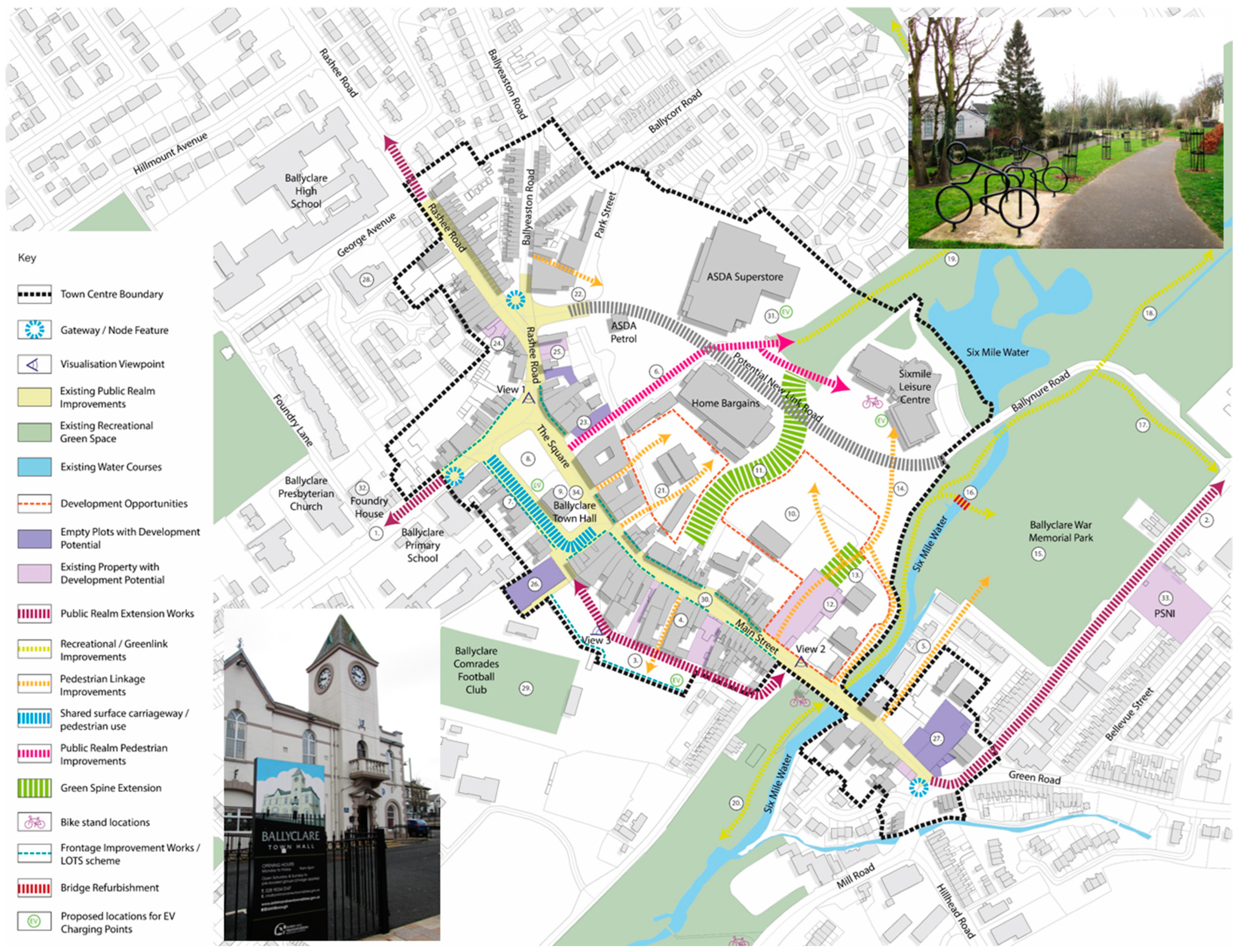

4.1. Ballyclare, Northern Ireland, U.K.

4.2. Leiria, Portugal

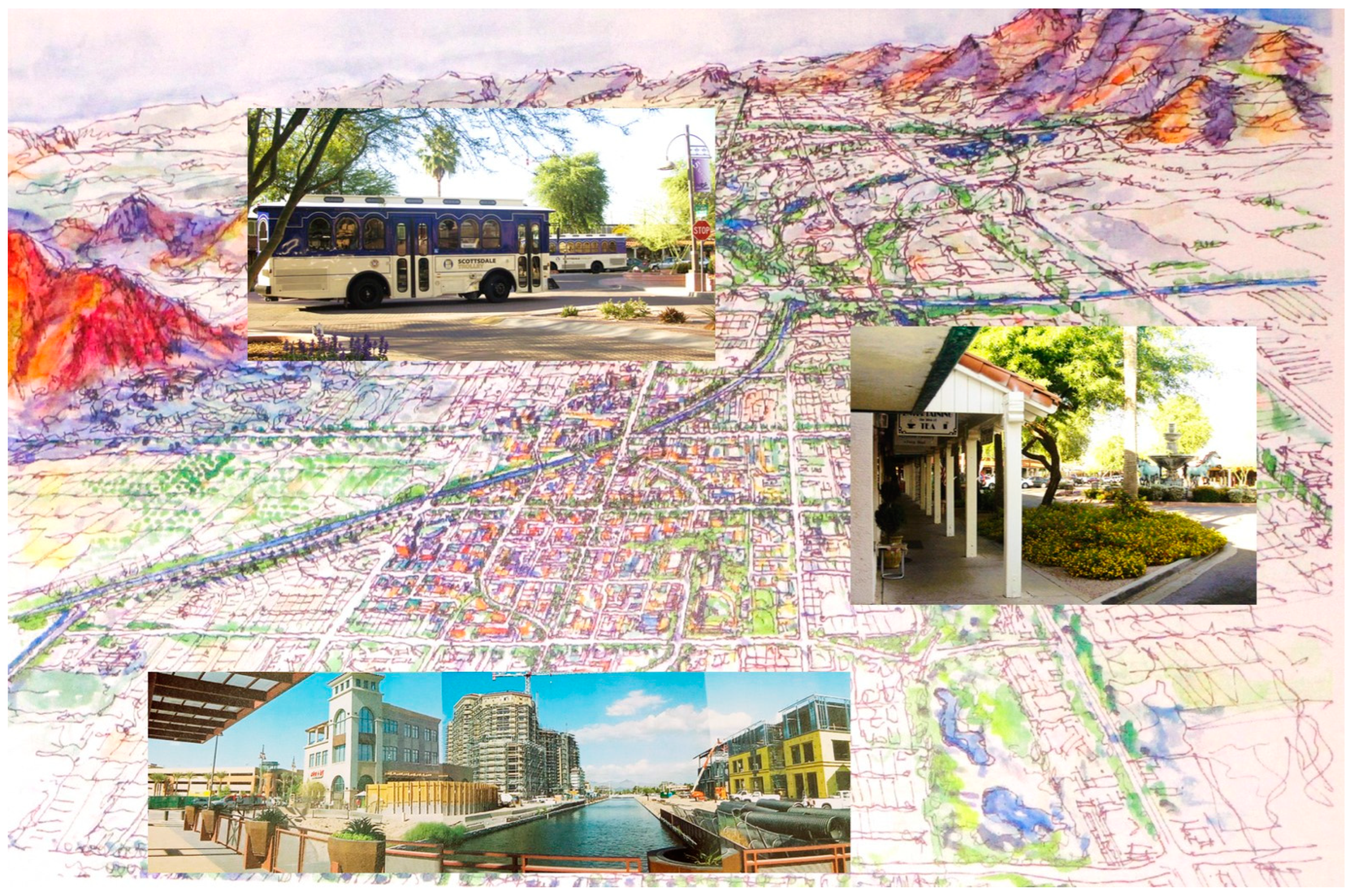

4.3. Scottsdale, AZ, U.S.

5. Comparative Analysis and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Shlomo, A. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Prytherch, D. Law, Engineering, and the American Right-of-Way: Imagining a More Just Street; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Kryazheva, Y.; Rudd, A.; Salingaros, N.A. A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions: Places, Networks, Processes; Sustasis: Portland, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mundigo, A.I.; Crouch, D.P. The city planning ordinances of the laws of the indies revisited: Part I: Their philosophy and implications. Town Plann. Rev. 1977, 48, 247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rossa, W. A Urbe e o Traço: Uma Década de Estudos Sobre o Urbanismo Português; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- American Planning Association. Planning and Urban Design Standards; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T. Cool walkability planning: Providing pedestrian thermal comfort in hot climate cities. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2023, 9, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dyason, D.; Fieger, P.; Rice, J. Greened shopping spaces and pedestrian shopping interactions: The case of Christchurch. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plann. Ass. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; Pafka, E. What is walkability? The urban DMA. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. International methods and local factors of Walkability: A bibliometric analysis and review. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2022, 148, 03122003. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C. Sustainable Urbanism: Riverfront greenway planning from tradition to innovation. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci Res. 2024, 37, 561–581. [Google Scholar]

- Fahimi, A.; Majedi, H.; Zabihi, H. Place as an output of codes: Importance of being place-character base of form-based codes. Int. J. Appl. Arts Stud. 2020, 5, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, S.; Clifton, K. Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel. Transportation 2001, 28, 317–346. [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll, C.; Crowley, F.; Doran, J.; McCarthy, N. Retail sprawl and CO2 emissions: Retail centres in Irish cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 102, 103376. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J. How codes shaped development in the United States, and why they should be changed. In Urban Coding and Planning; Marshall, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, S. (Ed.) Urban Coding and Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Joseph, E. Future of standards and rules in shaping place: Beyond the urban genetic code. J. Urb. Plann. Dev. 2004, 130, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Joseph, E. The Code of the City: Standards and the Hidden Language of Place Making; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.; Ulmer, J.; Appleyard, B.; Bigazzi, A. Complete and healthy streets. In The New Companion to Urban Design; Banerjee, T., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 448–463. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Ntounis, N.; Millington, S.; Quin, S.; Castillo-Villar, F.R. Improving the vitality and viability of the U.K. High Street by 2020: Identifying priorities and a framework for action. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 310–348. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Gong, C. Exploring the creation of ecological historic district through comparing and analyzing four typical revitalized historic districts. Energy Procedia 2017, 115, 308–320. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C. Exciting walk-only precincts in Asia, Europe and North-America. Cities 2021, 112, 103129. [Google Scholar]

- Rudlin, D.; Payne, V.; Montague, L. High Street: How Our Town Centres Can Bounce Back from the Retail Crisis; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Torrens, P. Smart and sentient retail high streets. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1670–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, L.; Gray, B.; Rodgers, D. Living Streets: Strategies for Crafting Public Space; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonzo, M. To walk or not to walk? The hierarchy of walking needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, I.; Feehan, C. Active transport and the journey to work in Northern Ireland: A longitudinal perspective 1991–2011. Econ. Themes 2023, 61, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marques da Costa, N.; Louro, A.; Marques da Costa, E. Transporte e Cidades Saudáveis: Realidades, políticas e intervenções em Portugal. In Cidade e Campo: Olhares de Brasil e Portugal; Marafon, G., Marques da Costa, E., Eds.; ED-UERJ: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Beske, J.; Dixon, D. (Eds.) Suburban Remix: Creating the Next Generation of Urban Places; Island Press: Washinton, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cabau, B.; Hernández-Lamas, P.; Woltjer, J. Regent’s Canal cityscape: From hidden waterway to identifying landmark. Lond. J. 2022, 47, 282–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifácio, A. The role of bluespaces for well-being and mental health in rivers as catalysts for the quality of urban life. In Urban and Metropolitan Rivers: Current Processes, Trends and Challenges; Cantos, J., Pérez, J., Riu, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, M.; Karbowiński, L. Why the riverside is an attractive urban corridor for bicycle transport and recreation. Cities 2023, 143, 104611. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanek, A.; Zingoni de Baro, M.; Newman, P. Biophilic streets: A design framework for creating multiple urban benefits. Sust. Earth 2020, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zawawi, A.; Porter, N.; Ives, C. Influences on greenways usage for active transportation: A systematic review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, E.; Joibari, S.S.; Salmanmahiny, A.; Hansen, R. Urban greenway planning: Identifying optimal locations for active travel corridors through individual mobility assessment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 101, 128464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kosonen, L.; Kenworthy, J. Theory of urban fabrics: Planning the walking, transit/public transport and automobile/motor car cities for reduced car dependency. Town Plann. Rev. 2016, 87, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Dovey, K.; Pafka, E. Towards a genealogy of urban shopping–Types, adaptations and resilience. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Melo Cartaxo, T. Resilience justice and adaptive law in European cities. In Urban Climate Resilience: The Role of Law; van der Berg, A., Verschuuren, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Glos, UK, 2022; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Louro, A.; Marques da Costa, N.; Marques da Costa, E. From livable communities to livable metropolis: Challenges for urban mobility in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Portugal). Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, A. ‘Every turn of the wheel is a revolution’: Towards the development of a cross-border greenways and cycle-route network in the Irish border region. Borderl. J. Spat. Plann. Irel. 2016, 5, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, R.; Dallat, M.; Tully, M.; Heron, L.; O’Neill, C.; Kee, F. Social return on investment analysis of an urban greenway. Cities Health 2022, 6, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Fabos, J.; Lindhult, M. Continuing a planning tradition: The New England greenway vision plan. Landsc. J. 2002, 21, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searns, R. Beyond Greenways: The Next Step for City Trails and Walking Routes; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buckman, S. Canal oriented development as waterfront place-making: An analysis of the built form. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAslan, D.; Buckman, S. Water and Asphalt: The impact of canals and streets on the development of Phoenix, Arizona, and the erosion of modernist planning. J. Southw. 2019, 61, 658–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, C.; Blair, N. Revitalising border towns and villages: Assets and potentiality in the Irish Border Region. J. Cross Bord. Stud. Irel. 2016, 11, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Haack, S. The art of scientific metaphors. Rev. Port. Filos. 2019, 75, 2049–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, J.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Blair, N. Weekly activity-travel behaviour in rural Northern Ireland: Differences by context and socio-demographic. Transportation 2012, 39, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, M.; Lee, J. The origin and development of markets: A business history perspective. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2011, 85, 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A. Ballyclare May Fair Through the Victorian Magic Lantern; CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AECOM. Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council Integrated Masterplan–Draft for Engagement. Available online: https://consultations.antrimandnewtownabbey.gov.uk/economic-development/antrim-and-newtownabbey-borough-council-masterplan/supporting_documents/ANIDF%20%20Report%20FINAL%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- mobilidadept. Plano Estratégico de Mobilidade e Transportes Município de Leiria–Fase I–Estudo de Caracterização e Diagnóstico 2015. Available online: https://www.pemtleiria.mobilidadept.com/gallery/pemt_leiria_fase_i.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Ministério do Ambiente e Ordenamento do Território. Programa Polis: Viver as Cidades; Programa Polis, M.A.O.T.D.R.: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cachinho, H. O centro da cidade de Leiria: Da glória do passado às incertezas do futuro. In A Nova Vida do Velho Centro nas Cidades Portuguesas e Brasileiras; Fernandes, J., Sposito, M., Eds.; CEGOT: Porto, Portugal, 2013; pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, I.; Condessa, B.; Patrício, M.; Bernardo, F. Urban regeneration projects in the eyes of the stakeholders: POLIS intervention in the city of Leiria (Portugal). In Proceeding Landscapes of Everyday Life Intersecting Perspectives on Research and Action; CEMAGREF & MEDDTL: Perpignan, France; Girona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.; Monteiro, D.; Matos, R.; Jacinto, M.; Antunes, R.; Gomes, P.; Amaro, N. Physical fitness of the older adult community living in Leiria, Portugal. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, A.C. Desert Vernacular: Green building and ecological design in Scottsdale, Arizona. In Design with the Desert: Conservation and Sustainable Development; Malloy, R., Brock, J., Floyd, A., Livingston, M., Webb, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, M. The old west of Old Town: Understanding visual simulacra as a means of staged authenticity. Cult. Stud. Crit. Methodol. 2014, 14, 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C. Redesigning the downtown of an expansive Sunbelt city: The Phoenix case. Plann. Pract. Res. 2020, 35, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- City of Scottsdale. Scottsdale Town Hall Workbook; City of Scottsdale and Arizona Town Hall: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaika, M. City of Flows: Modernity, Nature, and the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kodmany, K. New Suburbanism: Sustainable spatial patterns of tall buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, D. Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| City, Street(s), Population, [Creation Date] | Location of the Street(s), Environmental Amenities, and Main Reasons for Their Creation | Proportion of the Pedestrian Precincts and Green Open Spaces in Relation to the Cities’ Other Centres and Subcentres (Design, Length, Width, Layout, n. Blocks, n. Green Open Spaces) | Relationships Between the Streets and the Surrounding Areas and Activities, Including Greenways (Land Use, Urban Fabric, Type and Extension of Greenways) | Accessibility to the Pedestrian Precincts and Movement in the Streets and Through Greenways and Along Waterways (Access Points, Parking, Public Transport Hubs, Stops, Service Delivery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballyclare, N.I. (U.K.) Main Broad Street; 19 thousand inhabitants; 17th century (pedestrian improvements were conducted in mid-2010s onwards). | Main thoroughfare through the town centre; compact development; improvements to Lower Main Street and junctions with Ballynure Road and Mill Road, repaving of footpaths and kerbs in natural stone materials, undergrounding of unsightly utility cables. | Narrow 2-lane street with sidewalks on both sides, limited on-street parking, and bus stops; two large retail stores are adjacent to the town centre; no other competing sub-centres to speak of. | The town centre is surrounded by residential neighbourhoods, service functions are interspersed throughout town, and industrial areas are mostly on the edges of town; urban fabric mostly 1 and 2 story high; the Six Mile Water greenway transverses Main Street and provides leisure and recreational opportunities to residents and visitors; Ballyclare War Memorial Park located north of Main Street. | On- and off-street delivery to local establishments; car parking located adjacent to Town Hall and off Main Street with pedestrian alleyway linkages to the shops on Main Street; surface parking lots near the greenway with pedestrian bridges to the multi-use trails and playgrounds; interregional transit station withing walking distance of the main shopping district. |

| Leiria, (Portugal) More than 15 pedestrian streets in the historic district, including these main public spaces: Pr. Rodrigues Lobo; Pr. Goa Damião Dili; Lr. 5 Outubro; Jr. Luis Camões; R. D. Dinis; 129,000 pop. mun, (2021); c. 800 pop. historic centre (2011); pedestrianized in 1980s. | Most pedestrian streets located in the historic district, the main plazas, and the public garden provide accessibility to the urban fabric while functioning as interfaces between the historic district and the newly regenerated open spaces along the Lis River; multi-use trails, playgrounds, sports fields; outdoor cafes, skateboard park, physical exercise areas with gymnastic machines; the reasons for their creation were pedestrian safety, comfort, health, and pleasantness. | Most pedestrian streets in the city centre radiate out from the city’s main square Praça Rodrigues Lobo; 4 main other open spaces, 1 with a water feature; cobblestones with artistic designs; right of way for vehicles designed in the pavement; dropped kerbs for mobility impaired individuals; modern street furniture; public benches; landscaping. | Centuries-old urban fabric in the historic district; more modern built environment in the expanded city centre; higher building volumes near the city centre and greater distances between the built environment and the riverfront greenway farther away from the city centre; complementarity between opportunities for physical exercise near the city’s new stadium and swimming pools; 7-kilometre regenerated riverfront and multi-use trail. | Narrow streets in the historic district are difficult to access by emergency vehicles; extremely limited parking in the historic district; regular conflicts between circulating vehicles and parked cars and motorcycles; pedestrian tunnel under an arterial road adjacent to the Lis River; 11 pedestrian and 5 vehicular bridges over the Lis River throughout the city centre; local and regional bus station and taxicab main stop extremely well located in the city centre. |

| Scottsdale, A.Z. (U.S.) Civic Mall; East Main Street; Old Town Scottsdale; 2007 Downtown Scottsdale Pedestrian Mobility Study; 242,753 city-wide inhabitants in 2021 (7527 inhabitants downtown in 2006). | Orthogonal street grid-iron pattern with on-street parallel and angled parking in front of business establishments, and in the rear of buildings; continued building arcades to provide shade during hot summer months; Civic Mall is a pedestrian oasis of meandering walk-only paths, landscaped areas, trees, fountains; the pedestrian mobility study was conducted to create a physical inventory of 22 elements of the built environment (e.g., sidewalk with, surface/texture, clearance, obstructions, kerbs, alleys, amenities, shade, parking, etc.). | Most street space is still dedicated to moving and parked vehicles; sidewalks range in width, but some are more ample under the building-covered arcades; crossing arterial streets are two-lanes in each direction with a turn-lane in the middle; local streets are usually one lane in each direction; streetscaping typically comprises Xeriscaping with desert species (e.g., cacti, succulents, and palm trees) | The Old Town, the Main Street Arts District, and the Fifth Avenue districts are the most walkable areas. These districts also have the highest concentration of independent businesses; anchor destinations such as the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art and Scottsdale’s Museum of the West tend to be less walkable; planting strips provide buffers between sidewalks and parked cars; access to the Indian Bend Wash from downtown is done via alleyways and pedestrian passageways. | Two pedestrian bridges (South Bridge, Soleri Bridge) enable access to the Arizona Canal and the South Canal Plaza; many visitors access the downtown districts with automobiles; given the clusters of similar activities (i.e., Western and Native American souvenir shops; art galleries; museums; bars, restaurants, night clubs) they are likely to walk to visit key attractions; the downtown edges are less dense and have more surface parking lots; transit station is located on the southwest corner; trolley services provides convenient mobility options; deliveries are done from the street and via the rear of buildings. |

| City, Street(s), Population, [Creation Date] | Conciliation Between the Needs of Different Street and Greenway Users (Pavement Materials, Amenities, Landscaping, Stalls, Signage, Uniform Design Features) | Strategies to Respond to the Competition from New and Emerging Centres and Greenways Elsewhere (Uses of Public Spaces, Permitted Activities, Organized Events) | Funding of Improvements and Continued Management and Maintenance Activities (Organizations, Stakeholders, Funding Sources, Budgets) | Perpetuation of Success and Avoidance of Decline via Programming of Open Spaces and Greenways (Unique Features of Each Street and Open Spaces) |

| Ballyclare, N.I. (U.K.) | Pedestrians are protected by bollards and chains, street furniture, murals on walls at key locations, garden benches, trout sanctuary area (catch and release); elevated wooden nature observation decks; limited display of goods for sale on the sidewalk. | Monocentric urban development; proposed removal of railings around Town Hall; Ballyclare’s May Fair annual event; parades; open air free market; live music; etc. | GBP 437,000 in 2016 worth of improvements from N.I. Department for Social Development and Antrim and Newtownabbey Council; marketing efforts assisted by the local chamber of trade. | Regular maintenance of public spaces; improvements to green open spaces; augmenting accessibility to key services; Main Street’s beautification activities; permeability with adjacent spaces; Shop Frontage improvements; Live over Shop program; continuation of the May Fair. |

| Leiria, (Portugal) | Cobblestones with artistic designs; street furniture; dropped kerbs, and at level shared public spaces with motorized traffic; landscaping and shade trees in the main public open spaces; wayfinding signage. | Memorials, public art, sculptures, landscaping, wayfinding signage, fountains, benches; right of way for vehicles designed in the pavement; outdoor seating and cafés; multiple stairs and elevator to the castle; bollards to preclude abusive parking on sidewalks; modern recycling and solid waste bins. | Retail modernization and upgrading of public spaces and streets in the historic district defrayed by E.U., national, and municipal partnership funds; POLIS program utilized for the environmental and urban regeneration of the riverine environment; local chamber of commerce and individual retailers’ contributions to marketing the improvements and to attract additional visitors; conversion of a former public market (Mercado de Santana) into an arts and culture centre. | Four-kilometre pedestrian route through the historic district and along the riverfront; regular festivals, recreational and sports events, and celebration of local authors’ contributions to national literature (e.g., culinary festival; Rota do Crime; Writers’ Square). |

| Scottsdale, A.Z. (U.S.) | Shade is extremely important for pedestrians during the hot desert months; building arcades, spray mists, and shade trees provide relief from inclement weather; traffic calming devices (bulb outs, marked crosswalks, landscaped-medians, mini-circles, protected left-turn lanes, etc.) guarantee some safety to pedestrians; wayfinding signage; Western-style architecture (adobe construction, front porches); back alleys enable delivery to main buildings. | Cluster development; traffic calming; public art (sculptures, Western motifs, Xeriscaping); complementary land uses (e.g., entertainment and hotels; services, education, and health services); regular art walks, annual culinary festivals; various parades; building of mixed-use developments (retail and other auxiliary services on ground floor, and office and housing above). | More than an estimated USD 2 billion in investment in recent years; infill development and retrofitting of existing vacant lots, especially in more central locations; private developers, corporate investment, independent retailers and business entrepreneurs; partnerships with the local chamber of commerce. | To augment downtown’s endogenous features (indigenous, Native American, and Western sensibilities); strengthen its character and identity; grow the various clusters already present in the downtown area; utilize placemaking characteristics; employ biophilia and other urban and environmental urban design and regeneration strategies; consider the safety, comfort and pleasurability of the walking experience; reduce any potential vehicular-pedestrian conflicts; capitalize on the area’s natural (e.g., greenbelt) and man-made environments (irrigation canal). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balsas, C.J.L.; Blair, N. Walkable and Sustainable City Centre Greenway Planning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072897

Balsas CJL, Blair N. Walkable and Sustainable City Centre Greenway Planning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072897

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalsas, Carlos J. L., and Neale Blair. 2025. "Walkable and Sustainable City Centre Greenway Planning" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072897

APA StyleBalsas, C. J. L., & Blair, N. (2025). Walkable and Sustainable City Centre Greenway Planning. Sustainability, 17(7), 2897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072897