1. Introduction

Transforming post-airport areas, though infrequent, always presents significant challenges—design, social, and political [

1]. The design challenges stem from the vast area (often larger than many small towns), whose planned development brings both opportunities and risks. The opportunities are evident and enticing to many investors, planners, and designers. There is great scope for implementing bold urban and architectural ideas, guided by potentially accurate investor directives and constrained by local building and spatial regulations [

2].

The risks include losing the main idea and clarity of the layout (due to excessive fragmentation of investment and design units, resulting from diverse land ownership), and the risk of creating monotonous, large-scale uniformity in architecture and urban planning when entrusted to a single creator or team—appealing from a bird’s-eye view but not necessarily from a pedestrian’s perspective. Additionally, the typically long process of developing abandoned areas can lead to outdated social needs and design trends, though it may result in more diverse architecture better suited to user expectations.

Social challenges involve making significant decisions that anticipate changing social needs (e.g., housing quality and style) and development directions (not only for the city or region but also for the entire country). These decisions must include functional solutions that recognize and meet the needs, expectations, and aspirations of both local communities and newcomers, including people, companies, and corporations. The quality of urban and architectural solutions is crucial, as it can enhance the quality of life and business attractiveness of the developed area.

Political challenges involve difficulties in achieving consensus among governing groups at both national and local levels regarding the project’s justification, scope, implementation, and financing. Gaining social acceptance is challenging—referendums do not always yield satisfactory resolutions, and the growing diversification of European societies complicates or even excludes arbitrary decisions. Property disputes arise from the efforts of those controlling different parts of the land to secure their investment interests, typically between state ownership (State Treasury) and local ownership (Municipal Government). There is also a risk of local disputes over land use becoming entangled in broader political conflicts between competing factions.

In summary, the challenges include the vast area of the planned project, the absolute change of function, the need for coordination and monitoring of the investment process at various decision-making levels, and environmental and ecological conditions. This leads to the goal of this article: to build a theoretical foundation for urban transformations of post-airport areas. Practically, considering that such projects have been, are, and will likely be undertaken (albeit sporadically) in other locations, presenting the path to their realization may be useful for those facing similar challenges in the future.

1.1. State of Knowledge

Unlike the topic of airport urbanism [

3], the issue of large-scale transformations of post-airport areas, especially in contemporary times, has not yet been extensively reflected in the literature. Available resources include only brief descriptions and/or more detailed articles presenting specific aspects of individual projects [

4,

5].

A valuable comprehensive work is “Airport Landscapes” by Sonja Dümpelmann and Charles Waldheim [

6], illustrating existing, future, and hypothetical transformations of these areas from a landscape and even artistic perspective. However, urban planning issues are less addressed, and the process itself is not considered.

Among works describing individual examples with a broad social context, “Berlin Tempelhof, aus den Archives” [

7] is noteworthy, containing rich archival material that helps us understand the turbulent history of the failed transformation. The Tempelhof case has generally quite a broad range of literature as it embraces various disciplines [

8].

The literature on the Vienna Aspern housing estate is also quite extensive, as this example has gained popularity as a model housing estate. However, the airport aspect is generally not explored.

Regarding new transformations, only superficial press notes are generally available, highlighting one selected aspect. In contrast, the knowledge about the general scope of brownfield transformations is vast. A novel literature review is offered by He et al. [

9].

Transformations of post-airport areas into new urban districts are rare [

10] and there is no established theory for such transformations. Preliminary remarks on the context require formulating hypotheses that need verification, which this article aims to contribute to. The primary reason is the relatively small number of airports compared to the number of cities worldwide. Significant urban transformations of post-airport areas can occur when most of the following conditions are met:

The closed airport is large enough that its area and impact zone constitute a significant resource for the developing city.

The city is growing dynamically, creating substantial pressure on undeveloped land, and this growth organically includes the airport area.

The restrictions imposed by the city on the airport’s operation are significant enough to hinder its optimal functioning.

There is a need and pressure to expand the airport, which cannot be met due to the proximity of urban fabric.

The airport infrastructure is depreciated and outdated, making it relatively easy to decommission.

There are plans to build a new airport to replace the existing one.

In European locations, where this paper puts major emphasis, due to the spatial density of development, there are often cases of urban pressure on airport areas and related spatial conflicts. However, due to an “early start”, spatial transformations largely occurred around the mid-20th century, and the geography of airports is now roughly stabilized, though not entirely [

11]. In non-European locations, initial airport sites were generally further from city centers, providing a larger development buffer for the future. Additionally, in developing countries, new airport locations are relatively recent, meaning they have not yet worn out or depreciated. These caveats do not mean such cases did not occur.

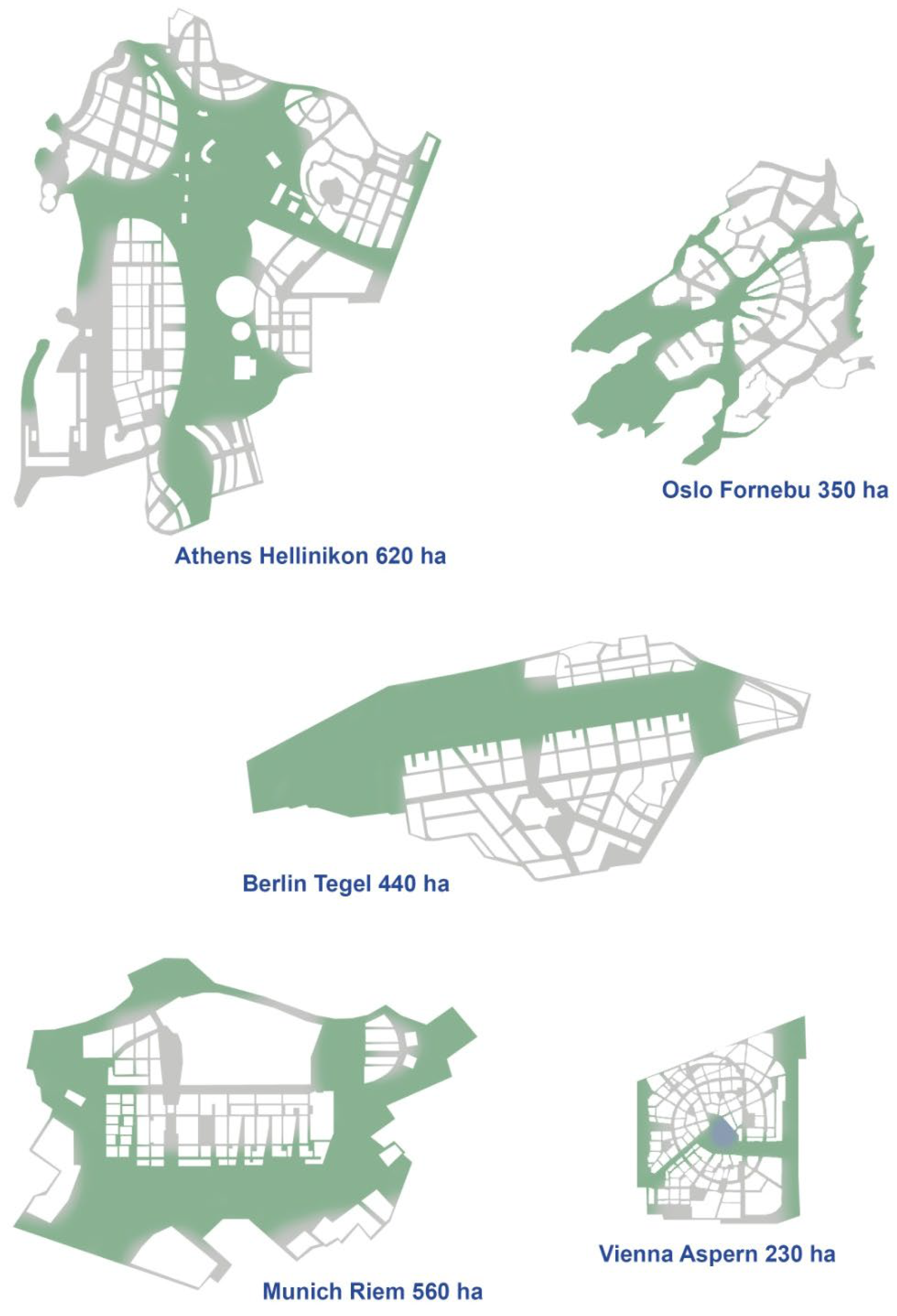

In Europe, Munich-Riem Airport operated from 1939 to 1992, playing a significant role in WWII and post-war aviation. Its closure led to the development of Messestadt Riem, a model of urban planning with residential, commercial, and recreational spaces, completed in the late 1990s. The Wien Aspern district, covering over 240 hectares, originally a military airport established in 1912, has transformed into a modern urban area. Ceasing operations in 1977, the site was redeveloped with residential units, commercial spaces, and an industrial park. This transformation integrates green spaces and advanced infrastructure to create a livable, eco-friendly environment. Ellinikon Airport in Athens, closed in 2001, became Ellinikon Metropolitan Park, a major urban regeneration project with extensive green spaces and sustainable development, which nevertheless raised some social concerns [

12]. (

Figure 1). Apart from Norway’s Fornebu, which is the subject of the current paper, Bodø Airport’s relocation led to a new, sustainable city district. On the other hand, Berlin Tempelhof Airport closed in 2008, and after a complex social and political process, was transformed into Tempelhofer Feld, one of the world’s largest urban parks, but without even minimally built-up areas allowed

Several other cases in Europe are currently in the design process or planning stages. This includes another Berlin airport—Tegel, and Warsaw’s Okęcie (Chopin Airport). In Lisbon, decisions to build a new airport were made in spring, 2024, and work is in the preliminary preparation stage (the purpose of the freed-up airport land has not yet been determined). In Budapest, after re-privatization in 2024, the decision to expand the existing airport was only recently made.

Globally, in Hong Kong, Kai Tak Airport (1925–1998) was redeveloped into the Kai Tak Development, encompassing over 320 hectares with residential, commercial, and recreational areas, including the Kai Tak Cruise Terminal and Kai Tak River, focusing on connectivity and walkability. In America, Floyd Bennett Field in NYC transitioned from a municipal airport to a recreational area within the Gateway National Recreation Area, promoting outdoor activities and environmental education. Toronto’s Downsview Airport was transformed into “City Nature”, focusing on green, high-density living and the “15-Minute City” concept, featuring 50,000 housing units and extensive parks.

Broadening the topic of post-airport area transformations, it is impossible not to notice the commonalities and differences with other “brownfield” transformations. Common elements include the secondary use of land and adaptable post-infrastructure facilities, as well as existing favorable transport solutions. Additionally, there is an opportunity to integrate the local community with new “tenants” of the area. A common challenge is the need for significant demolitions and remediation work.

The differences include the relatively small scale of building substance and the size of the area to be developed, necessitating the presence of not only large private investors but also state involvement. Social connotations differ from industrial areas, as post-airport areas are generally associated with prestige and modernity.

1.2. Article Structure

The article describing the process of transforming Fornebu Airport is divided into five chapters. The first is an introduction discussing the basics and assumptions of the study; the second describes the project’s chronological course (including the division into transformation stages); the third presents legal and organizational issues related to the investment; the fourth discusses the spatial and technical solutions applied; and the final chapter summarizes the discussed issues with conclusions. Chapters three and four also highlight issues corresponding to various aspects of the investment process.

1.3. Characteristics and Basic Data of the Project Background

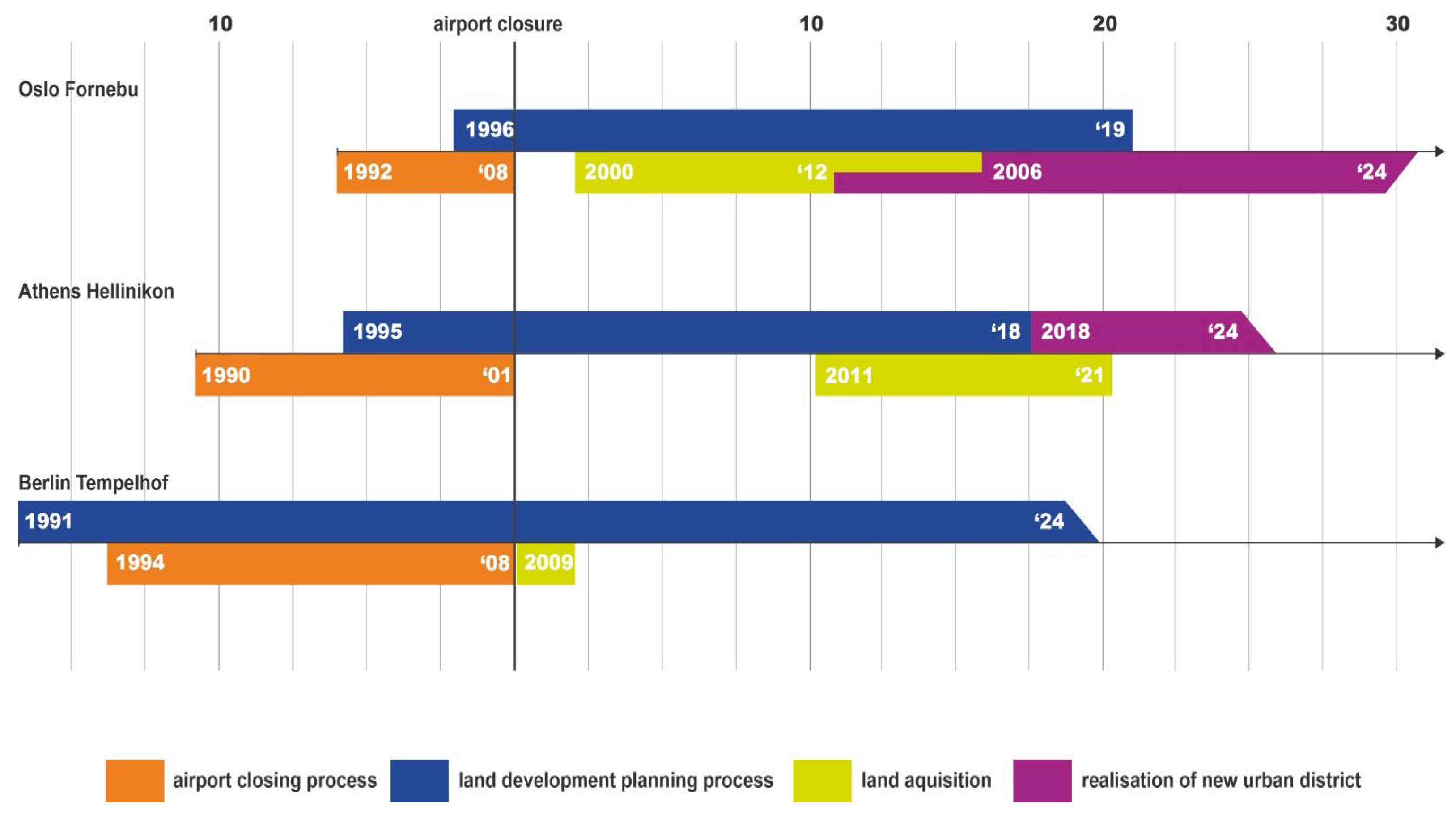

To understand the scale of the project, the following characteristic figures are provided (

Figure 2):

Date of land release–airport relocation: 1998 (decision to relocate in 1992)

Area to be developed: approximately 340 hectares

Ownership status: originally state-owned; currently state-owned for developer use and municipal ownership

Start of planning and design: 2001

Start of land division and sale: 2004

Start of construction works: 2007

Current investment status: approximately 88%

Planned completion date: 2030

Figure 2.

A comparison of a timeline of few post-airport developments in Europe aligned to the moment of closure. Source: authors.

Figure 2.

A comparison of a timeline of few post-airport developments in Europe aligned to the moment of closure. Source: authors.

The main entities involved in the process are as follows:

Avinor: A state-owned company under the Ministry of Transport and Communications, managing 43 state airports.

Baerum Kommune: The local municipality responsible for planning.

KLP Eiendom: A real estate development and management company owned by Kommunal Landspensjonskasse (KLP), which belongs to the municipalities and employers providing state employee pensions. It is the owner of several areas in Fornebu, including the Fornebu S shopping center.

OBOS: A special type of development company (with cooperative elements) that Norwegian citizens can join by paying fees, becoming shareholders, which comes with various benefits, such as priority in purchasing apartments (based on the length of fee payment). OBOS is the residential investor for most of the Fornebu areas covered by the master plan.

Statsbygg: A state-owned company responsible for managing and investing in public lands. In this case, it did not build independently but participated indirectly in land operations.

2. Method and Materials

This article is a case study examining the process of urban transformations and their current performance. It is informed by theoretical discourse but focuses primarily on practical experiences. The main elements studied are the historical transformation of Fornebu Airport into a multifunctional urban district and the current state of this district observed from various aspects.

The description of the past process is partly based on written sources. However, these sources, due to the recent nature of the events, are neither numerous nor exhaustive. Therefore, these sources were supplemented by field research through direct interviews with individuals and institutions involved in the process. These interviews are particularly interesting and valuable as they contain multiple viewpoints and involve people who remember the process from direct participation. It seems that now (2024) is the “last moment” to conduct such interviews, as the personnel who remember events from a quarter-century ago are becoming increasingly scarce, and many facts are being lost.

The description of the existing state also relies on direct interviews with individuals involved in the past and currently working for the Fornebu district. However, this description also uses written sources, particularly official publications on the subject—both official (more numerous) and research-based (less numerous due to the scarcity of material). The picture is completed by individual observation and assessment of the situation by the authorial team.

A key element of the research was a study site visit conducted in August and September 2023. This visit was part of a research pathway concerning non-operational airports in Europe, led by a Polish state-owned company responsible for constructing a new aviation hub. The key points of the program include the following:

Meeting with the representatives of Baerum municipality (where Fornebu Peninsula is located) responsible for spatial planning.

Meeting with Avinor, the state-owned company managing Norwegian airports, responsible for the relocation process and the launch of the new Gardermoen Airport.

Meeting with OBOS, the largest developer in Norway (operating under specific principles), the main residential investor in Fornebu (over the large-scale model of the entire development).

Meeting with KLM, another significant developer, responsible for the construction and management of the largest commercial facility in central Fornebu.

Visit to the construction site of the metro line and stations reaching Fornebu, combined with a meeting with the general contractor.

Meeting with representatives of the urban-architectural studio Rodeo Architekter, responsible for the Fornebu Sur project, a flagship investment of the revised transformation plan.

Tour of the eastern, office part of Fornebu, particularly the iconic Equinor building (headquarters of the state oil company) with the main designer from A-LAB studio.

Tour of the reference contemporary office part of central Oslo with the master plan designer for this area.

The site visit and interviews were conducted simultaneously, so visual reception accompanied personal reflections and explanations and guidance from the guides—local project participants (investors, designers, and builders).

Formulating conclusions required conducting an assessment. The problem lies in defining the criteria for the project’s success. It cannot be measured by urban parameters alone, as the number of square meters does not determine success (especially considering ecosystem needs). On the other hand, technical parameters (e.g., energy efficiency) are very limiting, as urban planning involves a wide variety of parameters. Social aspects, although extremely important, are difficult to measure at this stage. Economic evaluation is equally flawed. Over time, the financial efficiency of the transformation process loses significance compared to the quality of development achieved, which is much more durable than the budgets of individual units over several years.

This leads to the conclusion that the most appropriate criterion will be the quality of the built environment. This assessment will inevitably be subjective but can include not only the author’s opinion but also those identified during direct interviews with stakeholders during the study. It is also possible to compare this issue with similar processes, particularly in Europe.

4. Project Development and Planning Changes

4.1. Initial Planning/Master Plan 1

Planning for a new city district on the former airport site began before its closure in 1998. The first master plan (KDP-1), completed in 1996, formed the basis for an open urban planning competition. A participatory process involving local stakeholders and international planning experts preceded it, establishing broad guidelines for the competition. These included ground conditions, nature reserves, historic buildings, hazardous waste sites, contaminated areas, and development goals for Baerum municipality, Oslo, and the state of Norway. The concept envisioned housing for 20,000 people and 20,000 jobs at Fornebu. Oslo’s land (central peninsula) was designated for residential use, while the state-owned land (eastern coast, operated by the public company Statsbygg) was for office and commercial functions. The first master plan constituted a base for an urban design competition.

4.2. Competition and Master Plan 2

The aim of the international planning competition held in 1998 was to find the best feasible plan to be used as the basis of master planning [

13]. The initial material provided to participants for consideration included the following: the qualities of the ground, surrounding nature, listed buildings, history of the visibility of the airport, sustainable development areas of polluted ground, traffic, and the conflicting growth objectives of the three landowners (Baerum, Oslo, and the Kingdom of Norway).

Finally, the jury selected a proposal by Finnish designers Helin and Siitonen. The main idea was to restore significant parts of the area to nature. Landscape solutions were derived from the spatial structure. A central park was created, connected by seven linear green areas to the coast and fjords (the “octopus plan”). At its center is a lake, serving recreational purposes and as a retention reservoir. Emphasis was put on balancing privacy and community in residential and work areas. External block areas were divided into public, semi-public, and private zones. This concept was adapted for further planning at Fornebu.

The second master plan (Municipal Master Plan—KDP-2) emerged in 1999, proposing 6300 new homes, office spaces, extensive recreational areas, a bird reserve, commercial spaces (shopping center), services, and social infrastructure (including six schools). Parking spaces were limited, with stricter regulations than other Baerum areas. Both state and local regulations were tightened to introduce more energy-efficient and ecological solutions. The spatial layout, following the competition proposal, centered around a central park with radial extensions to the coasts, between which dispersed residential areas were located. The eastern coast was designated for commercial functions. The master plan proposed the rail public transport to Fornebu, initially without specifying whether it would be a metro or monorail (

Figure 3).

4.3. Early Development

Once the “mature” planning documents (KDP-2) were ready, actual development could be initiated, preceded by land operations. In 2000, the central, municipal portion of land was sold to Fornebu Boligspar, which then sold it to Scandinavian Property Development in 2007. Norway’s largest developer, OBOS, acquired the land in 2012 by purchasing Scandinavian Property Development. Subsequent transactions saw land sold entirely or in large parts.

4.4. Commercial and Residential Development

The first phase of spatial transformations involved the eastern part of the area, owned by the state company Statsbygg. This followed a strategic vision to create a major European technology hub modeled after America’s Silicon Valley. The first developed blocks included the headquarters of Telenor, with companies like Evry, Statoil (Equinor), and HP also establishing themselves there. The main goals were to create an international environment for IT development and innovation, establish interactions between research and capital (IT Fornebu was to host 4000 scientists), and create a national center for lifelong learning to make Norway a European leader in online education. The Norwegian parliament even approved a relaxation of migration policies to attract international researchers.

A significant and iconic building for these plans was the IT Fornebu Portal, an extension of the requalified old airport terminal (opened in 1964, designed by Odd Nansen, son of the famous polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen). It housed a business and incubation center for IT companies. The building, covering about 28,000 m2, was programmed by IT-Fornebu Eiendom and designed by A-lab Architects. The project aimed to reflect the vision of Fornebu’s new business center and set the standard of sustainability for the whole district. The facility consists of four glass office buildings and an externally accessible Hub covered with mandarin-red aluminum panels, intended to be a station for the planned monorail.

IT Fornebu, a state-owned company, was established to manage the area’s development. During the dynamic growth of the digital industry at the turn of the 21st century, this ambitious plan seemed realistic and attractive. However, the global IT market crash (IT bubble) significantly impacted the project’s implementation. For IT Fornebu, this meant a slowdown and gradual transformation into a regular office district.

Residential development followed the abovementioned commercial function. Initially, it involved limited areas on the south. The first residential estates began to develop in the early 2000s. The initial development was quite extensive, generally 2–4 stories high, with loose layouts. Over time, denser residential estates began to emerge, but still far from an urban character. The culmination of this phase was the construction of a shopping mall in central Fornebu.

The transport within the district and to the Oslo center was provided by a bus with numerous stops throughout the peninsula.

4.5. Master Plan 3 and Densification

In the second decade of the 21st century, Norway’s socio-economic development remained dynamic, particularly in the Oslo metropolitan area [

14]. With limited expansion possibilities due to natural constraints (fjords and forests), the city began to intensively seek new areas among those already developed, including Fornebu. Between 2014 and 2016, efforts to increase building density led to the redefinition of the 1999 master plan. Beyond demographic needs, this was driven by the development of urban culture in Norway, where a dynamic and young middle class began to appreciate the “downtown” lifestyle over suburban “peace and quiet”. These issues were explored in a workshop process involving current and potential residents. The main goal for renewed planning was to create a compact city instead of buildings scattered in the landscape. The number of planned housing units increased significantly from 6300 to 11,000.

This quantitative leap required efficient public transport to Oslo’s center. The metro was chosen as the primary mode of transport, both a cause and condition for Fornebu’s densification. The metro line was planned to have three stations closely linked to planned urban centers. With already-developed central and western zones, densification was planned for the central-eastern strip. This structurally shifted the project’s focus from the central park (extensively built) to a new development strip along the metro.

The rigid functional zoning (residential, office, and work-related) was also corrected.

In architectural typology, the third master plan moves away from green-buffered estates towards more urban development, with higher density and buildings closer to streets. Instead of rigid parameters, more flexible rules (e.g., average height) were introduced, along with a rich mix of functions in residential areas. Diversity in building types, forms, colors, and heights was emphasized. The third master plan (Municipal Area Plan—KDP-3) was completed in 2019 after a long process of considerations and negotiations. Its implementation is currently ongoing (2024) (

Figure 4).

5. Conclusions—Key Challenges and Controversies

5.1. Assessment and Lessons Learned

Drawing conclusions from such a multifaceted and extended process requires a meta-level assessment, which, as indicated in the methodological section, will be somewhat imperfect but acceptable given the article’s general nature.

Overall, the transformation of Fornebu’s post-airport areas can be considered a success. The primary criterion is the completion of the transformation itself, which objectively contributed to the effective use of the post-airport land. Despite some flaws, these transformations are generally viewed positively and are widely regarded as successful. Fornebu Peninsula is an attractive residential location in the Oslo region and is recommended for tourism on various websites. Unlike similar projects in Berlin [

15] and Athens, this location does not appear in the context of social conflicts.

A detailed assessment of Fornebu’s urban transformations would require separate studies focused on environmental, social, and economic factors, as well as more time. This is not the direct aim of this text.

It is possible, however, to highlight the most problematic issues, controversies, and key points, which hold both theoretical and practical significance. The former arises from the previously mentioned underdeveloped theory regarding the redevelopment of post-airport areas and the pressing need to expand knowledge in this field. The latter pertains to the clear applicability of these lessons for future analogous transformations.

Each selected point will be discussed not only in the context of the specific case of the redevelopment but also with consideration of comparative examples and theoretical frameworks.

5.2. Public Land Ownership

Land ownership stands out as a distinctive issue when transforming post-airport areas, distinguishing it from other large-scale urban projects. While post-industrial brownfields often involve predominantly private ownership, with some public entities involved, former airport areas are typically entirely public. Within this category, it is crucial to differentiate between municipal and state ownership, as these two types, despite their superficial similarities, have significantly different characteristics.

The financial and strategic goals of local governments and state treasuries are often vastly different, and these entities are frequently aligned with opposing political sides. Their planning tools also differ depending on the national governance system.

The closure of Fornebu Airport, managed by a state operator, raised debates over land use and ownership. This issue became more pronounced with the planned functional division: state-owned offices in the eastern part, and municipal residential and service zones in the central area. Initially, the land was to be transferred to the Norwegian State Treasury; however, citing pre-airport ownership, Oslo municipality claimed it. After legal proceedings, a significant portion of the land was returned to Oslo, although it is within Baerum’s administrative borders.

The eventual division resulted in equal-sized areas with markedly different characteristics. It is difficult to determine to what extent the current form of these two regions stems from design decisions during the competition and master planning stages or from the nature of the original owners. Notably, the state-controlled eastern area was dominated by large-scale office developments, including state-owned company headquarters, while the municipal central and western areas were primarily allocated for residential use. Each entity acted in line with its interests and focus.

Ultimately, the original development proposals for each sub-area became somewhat insular and functionally limited. Despite the establishment of a unified master plan to enforce a cohesive spatial and functional structure, the two areas became overly independent. This lack of coordination may result less from the inherent diversity of stakeholders and more from their excessive influence. The following question arises: is a significant entity like the State Treasury too rigid to adapt to locally crafted regulations? Moreover, the most urbanistically mature area—both spatially and functionally—appears to be the boundary zone between these two ownership sub-areas.

Local-level transactions in land development play a critical role in shaping the entire process in large-scale urban transformations, such as redeveloping post-airport areas. Variables in this process include the nature and role of initial public operators, the selection of eligible buyers, transaction modes and criteria, the division of land into subplots, and the timing of transactions. These elements can, to varying degrees, be incorporated into the master plan.

At Fornebu, unlike at Aspern in Vienna (considered a model for master planning and implementation), early land operations seemed only marginally planned. While the master plan largely determined the spatial aspects of urban transformation, operational guidelines were secondary. Selling extensive land parcels to a single entity, while convenient, reduces public oversight and raises questions about maximizing returns.

Additionally, land transactions caused some controversy due to their lack of transparency. Some sales occurred just before the introduction of developer fees for transport and social infrastructure, allowing sellers to obtain favorable prices without informing buyers that future investment returns might be lower due to public investment contributions.

It seems that planning the entire transformation process should more rigorously regulate the principles of land sale operations and the associated phasing of investment implementation. This approach was not only applied in Aspern but also in the analogous post-airport case of Hellenikon in Athens.

5.3. Developer Contribution

The financial contribution of entities responsible for development toward necessary infrastructure and public spaces is another critical and challenging issue. Approaches range from full responsibility (including financial) of developers, to entrusting this entirely to public entities, assuming that commercial entities contribute through the sale of land at appropriately high prices.

The first approach suits projects where a single strong entity oversees investments and derives long-term profits. For instance, in Athens, a dominant developer not only executes projects but also manages local areas and maintains public parks. The second approach is applicable to projects under strong public control, implemented by numerous and fragmented entities, as seen in Aspern. Both paths have unique advantages and disadvantages, requiring distinct tools (legislative, financial, organizational, and planning) and merit separate comparative analyses.

At Fornebu, an intermediate path was adopted. Most initial investments were made by a public entity, covering land remediation and preparation, infrastructure development, and the creation of a central park.

Maintenance is managed through an association, with each parcel contributing to operating costs. Some obligations are universally outlined in planning documents, while others result from specific agreements between developers and Baerum municipality responsible for infrastructure provision. However, the scale of specialized legislative solutions is insufficient to establish a distinct regulatory framework for this estate.

Although significant problems were ultimately avoided, this issue appears once again to have been insufficiently addressed within the master plan.

5.4. Functional Program

Functional program guidelines are a critical aspect of large-scale urban transformations. For public land, such as post-airport sites, potential land uses extend beyond merely profitable functions to include “strategic” purposes aligned with local or state interests. This flexibility can sometimes challenge the necessity of any development, as was seen with Berlin’s Tempelhof.

Broadly speaking, functional program elements can be categorized as regular—primarily residential, with additional office, commercial, and hotel uses—and special, serving supra-local needs. The latter may include sports facilities, exhibition centers, entertainment and recreation complexes, or themed developments aimed at fulfilling a specific developmental vision.

At Fornebu, the predominant focus was on regular uses, yet a significant stage during planning involved the ambitious Fornebu IT project. This vision aimed to create an educational, technological, and business cluster but ultimately fell far short of expectations. The eastern part of Fornebu now functions as a typical office cluster, lacking the educational, exhibition, or community-oriented functions initially envisioned. This calls into question the feasibility of such initiatives.

A safer route seems to be the realization of regular urban functions, particularly residential uses, which consistently meet demand and contribute to creating a livable city. In contrast, bold plans for “creativity clusters”, despite infrastructure and funding, tend to be somewhat utopian. It is worth questioning whether concepts like creativity or innovation can be effectively “built”. This serves as a cautionary note, particularly for the redevelopment of Berlin Tegel Airport, where the vision similarly focuses on a modern technology hub.

That said, “innovative” narratives play a significant role in place branding, fostering local identity, and contributing to the urban and financial success of spatial transformations.

5.5. Spatial Structure

Another critical aspect is the urban structure, analyzed both at the macro scale—its functional and spatial layout—and the micro scale—focusing on relationships between built and open spaces. At the most general scale the layout is based on the concept of green fingers, often associated with Copenhagen planning [

16] but also promoted by numerous urban theorists, such as Christopher Alexander [

17].

The functional program for Fornebu’s development evolved over time, from the early, schematic assumptions of the first master plan. Between the adoption of the second (1999) and third (2019) master plans, significant changes in urban trends and economic and technological shifts required planning changes. The dominant urban model of the 1990s, rooted in modernist ideas, shifted towards more intensive and functionally diverse models.

The legacy of the first and second master plans is primarily the basic division into two monofunctional mega-areas (office and residential). Within the residential cluster, the modernist roots of the original plan are evident in the green buffers between collector roads and buildings, residential ground floors, and the concentration of commercial functions in a central mall. Currently, under the third master plan, these assumptions have been challenged, favoring mixed-use development with significant small-scale retail and services in active ground floors.

New residential areas have a more varied morphological character, ranging from single-family villas, small multi-family houses, to large multi-family buildings organized in clear block structures. In Fornebu Sør, a typically central development with high-rise buildings, urban squares, and a main street with ground-floor services is emerging.

The principle of average height has been introduced, to be maintained within each block. Individual buildings can deviate by a permitted number of floors up or down, ensuring overall balance.

The shift from a modernist city paradigm to a more traditional-based urban form is a widely recognized issue, extending beyond large-scale urban transformations. However, this transition becomes particularly evident in such cases due to the high concentration of new developments over a short period, which highlights shifting trends. This change is, to some extent, both natural and inevitable. Yet, it is crucial to remember that architectural elements, especially buildings, have long-lasting impacts. Their typological features significantly influence the surrounding area’s use for many years. Key aspects include ground-floor residential units, particularly those with private front gardens, window placements on facades, access from public spaces to building complexes, and building heights, which affect not only views but also the shading of surrounding areas.

Given the availability of substantial land for development, it appears reasonable to designate zones not based on their functional profile but rather on varying typological characteristics. This approach would not only encompass a spectrum from less to more intensive uses but also introduce qualitative variations, such as combining compact, low-rise structures with taller, dispersed ones, while maintaining comparable overall densities.

5.6. Transport Solutions

Among the aspects related to spatial development, transportation planning is one of the more objective, technical subfields. It is the subject of an engineering process, albeit a complex one, but is easier to measure than the multifaceted issues of urban design, which touch upon social sciences and even art.

Therefore, the transportation planning process for the newly developed Fornebu district can be evaluated in terms of providing efficient and convenient public and private transportation.

Undoubtedly, it constitutes one of the weakest points of the entire Fornebu transformation. The failure to provide rapid and efficient public transportation to a newly developed district of such size and importance is a mistake from the perspective of theories like transit-oriented development and, more generally, rational urban development. It is particularly surprising because the lack of efficient access was one of the fundamental drawbacks of the former airport location, which contributed to its closure. The observation that the new development of the former airport grounds would equally require rapid access to the city center was not made.

Secondary design decisions, such as minimizing parking spaces within the district, developing a network of bicycle routes, and providing numerous bus stops, were not able to effectively connect the district with the center of Oslo, making it still appear distant in the eyes of residents and users.

This situation required concrete plans for improving public transport access. In 2015–2016, the plan for the underground Fornebu Line metro was approved, connecting the new district to Majorstuen and the existing Oslo network. The line will be 7.7 km long with six new stops, taking 12 min to travel. Three stops will be in the Fornebu district, each linked to one of the three new local centers. Completion is planned for 2025.

Interestingly, the accelerated decision and implementation of the metro line coincided with a significant increase in allowed building density and target population. Only the promise of increased land value profits for developers allowed them to contribute more significantly to the metro line’s implementation (contribution estimated at 30%). It is reasonable to question whether the initial population assumptions were underestimated and whether it was necessary to pursue the rail connection from the outset.

Another issue is access to the district by car. Former airport grounds are usually conveniently connected due to their original function. However, the nature of airport access, which is fairly evenly distributed throughout the day, is different from access to a residential and office district, where traffic occurs in distinct morning and afternoon peaks. In this case, access based on an multi-lane [

18] arterial road is less reliable than a more diverse network of multiple connections.

5.7. Landscape and Open Space Design

The role of urban greenery is multifaceted, ranging from habitat functions for various species to blue-green infrastructure that promotes water retention, social, esthetic, and cultural benefits.

The landscape solutions are derived from the spatial structure proposed in the winning competition entry, reflected in the second master plan. A central park was created, connected by seven linear green areas to the coast and fjords (the “octopus plan”). At its center is a lake, serving recreational purposes and as a retention reservoir. To manage water flow, natural wetlands, biological sand filters, mechanical filters, and pumps were created to purify and aerate the water, ensuring good quality [

19]. The park’s design merges landscape solutions that highlight the local natural environment [

20] with recreational functions, particularly sports areas.

In practice, the natural aspects of this solution seem to be more successful than the social and cultural ones. This is particularly surprising, as the ecosystem value of urban green areas has only recently gained popularity in urban policies. Against this backdrop, the case of the early adoption of sustainable solutions in urban design stands out as an exceptional example.

On the other hand, the urban plan, which places extensive green areas as the main public spaces, fails to achieve the desired urbanity and vibrant city life. Ultimately, in the third master plan, the design of public spaces, in addition to the previously provided natural areas, is enriched with typical urban solutions, such as boulevards, commercial streets, and plazas, located near new metro stations. This empirically demonstrates that, despite being attractive and conducive to creating a sustainable living environment, green areas cannot adequately fulfill the functions of primary public spaces with social and cultural roles. In some cases, green areas actively hinder the creation of a compact city. This includes wide, poorly developed green buffers, remnants of the 1990s plans, separating buildings from the main streets, now seen as a design flaw for a compact city.

5.8. Pro-Ecological Solutions

Fornebu aims to achieve zero emissions, necessitating significant efforts to implement various technological and spatial solutions. New residential and office buildings are designed with energy efficiency in mind, incorporating advanced insulation, ventilation, and heating systems based on renewable energy from marine heat exchangers and two heating plants, as well as efficient lighting technologies.

Fornebu boasts the first passive-standard kindergarten and the Fornebu S shopping center, which is the only facility worldwide with a BREEAM “outstanding” certification. Innovative stormwater management solutions have been applied in the post-airport area, including delayed drainage, water retention, and rainwater irrigation techniques.

Despite these achievements, the ultimate assessment of the district’s sustainability remains challenging, particularly considering the inflation of the term’s significance. Paradoxically, it appears that the overall quality of the living environment may have a more significant impact on sustainability than strictly technological indicators and measured energy consumption.

5.9. Heritage Elements

The visibility of the district’s airport past in its current identity is debatable. Shortly after the airport’s closure, most of the infrastructure elements were removed, erasing the former character of the area. The few remaining testimonies include the terminal building and the control tower. The new spatial structure does not refer to the old runways in any way. This cannot be considered a flaw in itself, as airport infrastructure does not hold significant value for the daily life of the new district. However, in the context of creating a new part of the city that is still finding its identity, preserving more traces of the past could have been helpful. Instead, the focus was placed on emphasizing a new identity and seeking new narratives, such as a center for new technologies.

5.10. “Soft” Factors

Beyond these key factors for success, there are also other, often less tangible and sometimes even unconscious factors. Based on direct interviews with participants in this process, it can be stated that the specific “time-space moment” influenced the rapid development process: the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries was a very dynamic period in Europe and the world. During this development, urban planning and architecture held a prominent place, leading to the realization of numerous bold spatial visions on a scale not seen after the 2008 crisis [

21,

22]. Against this background, Norway’s development accelerated from a peripheral, moderately wealthy, and culturally passive country to a dynamic, very wealthy, and active player on the world stage [

23,

24], favoring ambitious development goals [

25]. Paradoxically, the lack of experience in such investments (unawareness of potential problems) also played a role.

Several factors support this interpretation, particularly related to the Fornebu IT/Technopolis campus. The belief in replicating Silicon Valley’s success by creating a physical environment may seem naive today (after the IT bubble), but the determination with which it was pursued provided significant momentum for investment activities. Some outcomes now appear controversial, such as the isolated monorail station reminiscent of amusement park solutions. However, as Rem Koolhaas’s classic “Delirious New York” shows, amusement park solutions have inspired new urban and architectural typologies.

An interesting thread in conversations is the reference to the “national character” of Norwegians (raised in interviews held during the research), combining adventurous courage with a certain nonchalance, exemplified by Thor Heyerdahl’s solo Pacific expedition on the Kon-Tiki raft.

These considerations suggest that such direct and unpretentious post-airport transformations might not be possible in the current historical moment.