Predictors of Intention to Quit Among Urban Bus Drivers in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Model

2.1. Related Studies of Turnover Intention

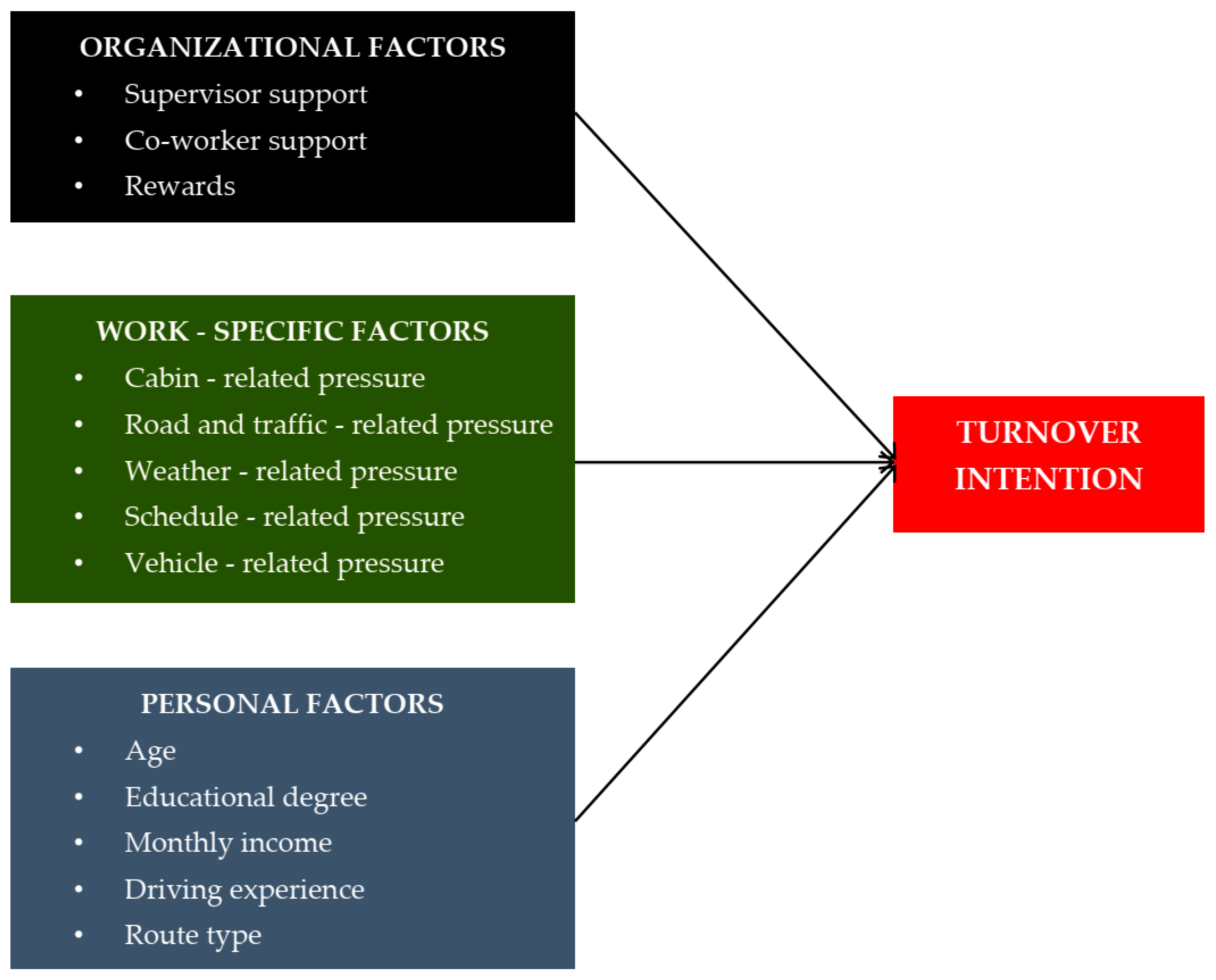

2.2. Research Model Formulation

2.2.1. Organizational Factors

2.2.2. Work-Specific Factors

2.2.3. Personal Factors (Employee-Related Factors)

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Research Setting

- 100% district coverage: 30 out of 30 districts, counties, and towns (100%);

- 88.4% commune coverage: 512 out of 579 communes, wards, and townships (an increase of two communes compared to 2021);

- 87% hospital coverage: 65 out of 75 hospitals;

- 67% education coverage: 192 out of 286 universities, colleges, and high schools;

- 100% industrial zone coverage: 27 out of 27 major industrial zones;

- 89.2% urban area coverage: 33 out of 37 urban areas;

- 95.8% craft village coverage: 23 out of 24 craft villages;

- 92% cultural and tourism site coverage: 23 out of 25 historical and cultural relic sites and tourist areas.

3.2. Data Collection

- Part 1 offered the survey’s purpose and scope. Drivers were instructed that they should take part in the survey once and were requested to give signed consent before entering the next sections;

- Part 2 comprised questions related to the drivers’ age, educational degree, monthly income, driving experience, and the types of routes on which respondents were working;

- Part 3 included 25 attitudinal statements regarding drivers’ perceptions (i.e., cabin-related pressure, road- and traffic-related pressure, weather-related pressure, schedule-related pressure, vehicle-related pressure, supervisor support, co-worker support, rewards, and turnover intention) measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Table 2).

3.3. Analytical Methods

- -

- Dependent variable: Turnover intention extracted from items using the EFA technique and treated as a continuous variable. The use of other logit methods such as logit regression was impossible, as there was no sound way of converting items of intention measurement into a binary one;

- -

- Independent variables: Observable variables treated as nominal ones and latent variables extracted from items using the EFA technique and treated as continuous variables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis

- (1)

- Pressure of cabin and vehicle;

- (2)

- Pressure of schedule;

- (3)

- Pressure of road and traffic;

- (4)

- Pressure of weather;

- (5)

- Organizational support;

- (6)

- Rewards.

4.2. Factors Associated with Turnover Intention Among Bus Drivers

4.3. Discussion

4.4. Policy Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| TRANSERCO | Hanoi Transportation Corporation |

| DOT | Department of Hanoi Transportation |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| VND | Vietnam dong |

References

- Alkahtani, A.H. Investigating Factors That Influence Employees’ Turnover Intention: A Review of Existing Empirical Works. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Nguyen Thi, B. What If Delivery Riders Quit? Challenges to Last-Mile Logistics during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 47, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heavey, A.L.; Holwerda, J.A.; Hausknecht, J.P. Causes and Consequences of Collective Turnover: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 412–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigliardi, B.; Petroni, A.; Ivo Dormio, A. Organizational Socialization, Career Aspirations and Turnover Intentions among Design Engineers. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hand, H.H.; Meglino, B.M. Review and Conceptual Analysis of the Employee Turnover Process. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Blake, R.S.; Goodman, D. Does Turnover Intention Matter? Evaluating the Usefulness of Turnover Intention Rate as a Predictor of Actual Turnover Rate. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 240–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intention, and Turnover: Path Analyses Based on Meta-Analytic Findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, G.R.; Abrams, D.; Retter, C.; Gunnarsdottir, S.; Ando, K. Identification as an Organizational Anchor: How Identification and Job Satisfaction Combine to Predict Turnover Intention. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.F.; Estelami, H. An Exploratory Study of Employee Turnover Indicators as Predictors of Customer Satisfaction. J. Serv. Mark. 2007, 21, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, B.C.; Burch, T.C. A Model of Turnover-Based Disruption in Customer Services. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yao, M. What Promotes Teachers’ Turnover Intention? Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, F.; Gumussoy, C.A.; Iskin, I. Factors Affecting Intention to Quit among IT Professionals in Turkey. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Weisberg, J. Exploring Turnover Intentions among Three Professional Groups of Employees. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2006, 9, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Lewis, G.B. Turnover Intention and Turnover Behavior: Implications for Retaining Federal Employees. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 32, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Min, H. (Kelly) Turnover Intention in the Hospitality Industry: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, K.; Pietarinen, J.; Pyhältö, K.; Soini, T.; Väisänen, P. Why Leave the Teaching Profession? A Longitudinal Approach to the Prevalence and Persistence of Teacher Turnover Intentions. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 837–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seston, E.; Hassell, K.; Ferguson, J.; Hann, M. Exploring the Relationship between Pharmacists’ Job Satisfaction, Intention to Quit the Profession, and Actual Quitting. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2009, 5, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Rafiq, M.; Chin, T. Employee Well-Being and Turnover Intention: Evidence from a Developing Country with Muslim Culture. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Nikkhah, A.; Farrokhi, P. Factors Influencing Healthcare Workers’ Intention to Leave during COVID-19: A Systematic Review in Middle- and Low-Income Countries. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D.E.; Macdonald, J.R.; Crum, M.R. The Influence of Workplace Justice Perceptions on Commercial Driver Turnover Intentions. J. Bus. Logist. 2011, 32, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.-D. Pandemic and Teacher Retention: Empirical Evidence from Expat Teachers in Southeast Asia during COVID-19. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 1141–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, M. A Concept Analysis of Turnover Intention: Implications for Nursing Management. Collegian 2010, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, H.-M. The Influence of Nurses’ Working Motivation and Job Satisfaction on Intention to Quit: An Empirical Investigation in Taiwan. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlove, E.E.; Guzell, J.R. Intention to Leave, Anticipated Reasons for Leaving, and 12-Month Turnover of Child Care Center Staff. Early Child. Res. Q. 1997, 12, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Rodwell, J.; Shacklock, K.; Farr-Wharton, R.; Demir, D. The Impact of Individual and Organizational Resources on Nurse Outcomes and Intent to Quit. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masum, A.K.M.; Azad, M.A.K.; Hoque, K.E.; Beh, L.-S.; Wanke, P.; Arslan, Ö. Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit: An Empirical Analysis of Nurses in Turkey. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMay, S.; Keller, S.B. Fifty Years inside the Minds of Truck Drivers. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Fournier, P.; Lamontagne, S. Relationships between Commitments to the Organization, the Superior and the Colleagues, and the Intention to Leave among Truckers. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2011, 19, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, S.M.; Douglas, M.A.; Roberts, M.D.; Overstreet, R.E. Leavin’ on My Mind: Influence of Safety Climate on Truck Drivers’ Job Attitudes and Intentions to Leave. Transp. J. 2017, 56, 184–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMay, S.A.; Johnson, L.; Williams, Z.; Garver, M. The Causes of Truck Driver Intent-to-quit: A Best-fit Regression Model. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2013, 23, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, S.A.; Taylor, G.S.; Turner, G.B. Driver Turnover and Management Policy: A Survey of Truckload Irregular Route Motor Carriers. Transp. J. 1993, 33, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bujold, A.; Parent-Rocheleau, X.; Gaudet, M.-C. Opacity behind the Wheel: The Relationship between Transparency of Algorithmic Management, Justice Perception, and Intention to Quit among Truck Drivers. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 8, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanning, T.; Tanning, L. The Turnover of Transportation Companies in the European Countries of the Former Eastern Bloc before and after the Economic Crisis. TEM J. 2013, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoo, S.; Verhofstadt, E. What Drives the Drivers? Predicting Turnover Intentions in the Belgian Bus and Coach Industry. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2016, 91, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Hsu, Y.-C. Taking a Closer Look at Bus Driver Emotional Exhaustion and Well-Being: Evidence from Taiwanese Urban Bus Drivers. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwei, R.J.; Hetzel, S.; Kim, K.; Mahoney, J.; DeYoung, K.; Frumer, J.; Lanzafame, R.P.; Madlof, J.; Simpson, A.; Zambrano-Morales, E.; et al. Peer-to-Peer Support and Changes in Health and Well-Being in Older Adults Over Time. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Moon, C.W.; Shin, J. Linkages between Empowering Leadership and Subjective Well-Being and Work Performance via Perceived Organizational and Co-Worker Support. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Z.; Younis, M.W.; Yasir, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Dilawar, M.; Yasin, M.; Hamza, M.; Shahzad, S.; Ali, M.S.; Jamil, A.; et al. Effects of Safety Pattern, Cabin Ergonomics, and Sleep on Work-Related Stress and Burnout of City and Transit Bus Drivers in Lahore, Pakistan. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallia, L.; Lazuras, L.; Violani, C.; Lucidi, F. Crash Risk and Aberrant Driving Behaviors among Bus Drivers: The Role of Personality and Attitudes towards Traffic Safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 79, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.L.M.; Flin, R.; Mearns, K. Bus Driver Well-Being Review: 50 Years of Research. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Huy, V.; Hoang-Tung, N.; Kubota, H. Effects of Mixed Traffic Flow and Time Pressure on Violated Driving Behaviors of Bus Drivers. Ergonomics 2024, 67, 1958–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Useche, S.A.; Gómez, V.; Cendales, B.; Alonso, F. Working Conditions, Job Strain, and Traffic Safety among Three Groups of Public Transport Drivers. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- af Wåhlberg, A.E. Characteristics of Low Speed Accidents with Buses in Public Transport. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2002, 34, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Li, Z.; Ci, Y.; Zhang, G. Risk Factors Affecting Fatal Bus Accident Severity: Their Impact on Different Types of Bus Drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 86, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompier, M.A.J.; Di Martino, V. Review of Bus Drivers’ Occupational Stress and Stress Prevention. Stress Med. 1995, 11, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu Thi, H.; Nguyen Thanh, C.; Vu Trong, T. Analysis of Factors Affecting Vehicle Choice Behavior in Hanoi City. Tạp chí Khoa học Giao thông vận tải 2024, 75, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakunmoju, S.; Woodruff, K.; Kim, H.H.; LeFevre, A.; Hong, M. Intention to Leave a Job: The Role of Individual Factors, Job Tension, and Supervisory Support. Adm. Soc. Work 2010, 34, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, C.M.; Deery-Schmitt, D.M. Factors Affecting Turnover among Family Child Care Providers: A Longitudinal Study. Early Child. Res. Q. 1996, 11, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Ha, T.T.; Tu, S.S.; Nguyen, T.C. Impediments to the Bus Rapid Transit Implementation in Developing Countries—A Typical Evidence from Hanoi. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2019, 4, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport. Restructuring the Hanoi Bus Network During the Period Between 2023–2030 and the Vision Towards 2045; Department of Transport: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024.

- Nguyen, T.C.; Nguyen, M.H.; Armoogum, J.; Ha, T.T. Bus Crash Severity in Hanoi, Vietnam. Safety 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. Why Are Hanoi Students Giving up on Bus Ridership? Transportation 2022, 50, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. Can Electric Buses Entice More Public Transport Use? Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 13, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. COVID-19 Need Not Spell the Death of Public Transport: Learning from Hanoi’s Safety Measures. J. Transp. Health 2021, 23, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. Chapter Two—Why Do Some BRT Systems in the Global South Fail to Perform or Expand? In Preparing for the New Era of Transport Policies: Learning from Experience; Shiftan, Y., Kamargianni, M., Eds.; Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H. Evaluating the Service Quality of the First Bus Rapid Transit Corridor in Hanoi City and Policy Implications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovations for Sustainable and Responsible Mining, Hanoi, Vietnam, 15–17 October 2020; Tien Bui, D., Tran, H.T., Bui, X.-N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. The Effect of Fuel Price Fluctuations on Utilitarian Cycling Rates: A Survey of Cyclists in Vietnam. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 115, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q. The Future of Personal Electric Mobility in Emerging Economies: A Survey of e-Moto Users in Vietnam. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 57, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.L.M.; Flin, R.; Mearns, K. Facets of Job Effort in Bus Driver Health: Deconstructing “Effort” in the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Xu, H. Analysis of Risky Driving Behaviors among Bus Drivers in China: The Role of Enterprise Management, External Environment and Attitudes towards Traffic Safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 168, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quy Nguyen-Phuoc, D.; Ngoc Thi Nguyen, L.; Ngoc Su, D.; Nguyen, M.H.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Deadly Meals: The Influence of Personal and Job Factors on Burnout and Risky Riding Behaviours of Food Delivery Motorcyclists. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, J.; Kline, T. The Relationships between Organizational and Individual Variables to On-the-Job Driver Accidents and Accident-Free Kilometres. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 1598–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.-L. Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model to Reduce the Aberrant Behavior of Bus Drivers: Let Them Play a Good Social Role. J. Transp. Health 2023, 33, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, T. Job Burnout, Effort-Reward Imbalance and Time Pressure as Predictors of Safety among Military Truck Drivers. J. Transp. Health 2022, 24, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczo, R.M.; Hanisch, K.A. An Examination of Behavioral Families of Organizational Withdrawal in Volunteer Workers and Paid Employees. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Nissly, J.A.; Levin, A. Antecedents to Retention and Turnover among Child Welfare, Social Work, and Other Human Service Employees: What Can We Learn from Past Research? A Review and Metanalysis. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2001, 75, 625–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H. Factors Influencing Home-Based Telework in Hanoi (Vietnam) during and after the COVID-19 Era. Transportation 2021, 48, 3207–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Armoogum, J. Perception and Preference for Home-Based Telework in the COVID-19 Era: A Gender-Based Analysis in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Five-Step Guide for Novices. Australas. J. Paramed. 2010, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudeck, R. 10—Exploratory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Tinsley, H.E.A., Brown, S.D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 265–296. ISBN 978-0-12-691360-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-107-09264-8. [Google Scholar]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Kilic, H. Relationships of Supervisor Support and Conflicts in the Work–Family Interface with the Selected Job Outcomes of Frontline Employees. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinko, V.; Cheberyachko, S.; Deryugin, O.; Tretyak, O.; Dusmatova, O. Assessment of the Risks of Occupational Diseases of the Passenger Bus Drivers. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkleby, M.A.; Ragland, D.R.; Fisher, J.M.; Syme, S.L. Excess Risk of Sickness and Disease in Bus Drivers: A Review and Synthesis of Epidemiological Studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1988, 17, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L.; Kottorp, A.; Winblad, B.; Nygård, L. Perceived Difficulty in Everyday Technology Use among Older Adults with or without Cognitive Deficits. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, L. Effects of Altruism and Burnout on Driving Behavior of Bus Drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 102, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlotan, O.; Drewry, H. Factors That Influence the Mental Health of Bus Drivers: A Systematic Review. Ment. Health Prev. 2024, 35, 200355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Mai, N.X.; Ho-Mai, N.T.; Nguyen, M.H.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What Factors Contribute to In-Role and Extra-Role Safety Behavior among Food Delivery Riders? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 102, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Non-Fatal Traffic Crashes among Food Delivery Riders in Vietnam: What Is the Problem? Traffic Inj. Prev. 2023, 24, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerl, H.; Stolz, E.; Großschädl, F.; Rásky, É.; Freidl, W. The Moderating Role of Personal Resources in the Relationship between Psychosocial Job Demands and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.L.; Pojani, D.; Nguyen, T.C.; Ha, T.T.; Nguyen, M.H. Why Is Vietnam a Motorcycle Nation? A Transport Psychology Study. Eur. Transp./Trasp. Eur. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, N.M.; Phuong, H.L.H.; Manh, N.D.; Duong, K.A.; Tung, T.T.; Hao, H.V.; Hieu, N.M. Exploring continuance intention to use electric motorcycles among students in Hanoi using expectation confirmation theory. Transp. Commun. Sci. J. 2023, 74, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.T.; Nguyen, M.H. Factors associated with bus subsidy in Hanoi—Using data of the whole network from 2011 to 2019. Transp. Commun. Sci. J. 2021, 72, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Number of Bus Routes | Number of Buses | Ridership (Million Passengers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 70 | 1189 | 458.8 |

| 2014 | 72 | 1206 | 463.5 |

| 2015 | 72 | 1208 | 431.7 |

| 2016 | 79 | 1291 | 394.9 |

| 2017 | 91 | 1497 | 392.3 |

| 2018 | 100 | 1599 | 404.4 |

| 2019 | 104 | 1663 | 430.1 |

| 2020 | 104 | 1678 | 343.4 |

| 2021 | 121 | 1879 | 194.2 |

| 2022 | 132 | 2033 | 333.9 |

| 2023 | 132 | 2024 | 365.1 |

| Code | Items | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CrP | Cabin-related pressure | [38,59] |

| CrP_1 | The passengers on the bus are often noisy, which makes me uncomfortable. | |

| CrP_2 | Passengers often do not follow or listen to the instructions of the staff while traveling on the bus, which makes me feel irritated. | |

| RrP | Road- and traffic-related pressure | [60] |

| RrP_1 | Buses have to share the road with other vehicles, which makes my job more stressful and exhausting. | |

| RrP_2 | Many routes have narrow widths and frequent congestion, which increases the pressure of my job. | |

| RrP_3 | Traffic in Hanoi has kept increasing, making my job more stressful. | |

| WrP | Weather-related pressure | [59] |

| WrP_1 | The summer weather in Hanoi is harsh with high temperatures, which adds more pressure to my job. | |

| WrP_2 | The winter weather in Hanoi is harsh with deep temperature drops, which also increases the pressure on my job. | |

| SrP | Schedule-related pressure | [41,59] |

| SrP_1 | The working hours each day are currently too long. | |

| SrP_2 | The resting time between trips is too short. | |

| SrP_3 | I often have to constantly switch shifts. | |

| SrP_4 | During my shift, I rarely have enough time to go to the restroom. | |

| SrP_5 | I’m always worried about the possibility of being fined for arriving at the terminals late. | |

| VrP | Vehicle-related pressure | [59] |

| VrP_1 | The bus I drive deteriorates quickly because it operates frequently, and the quality of maintenance and repairs is not good enough. | |

| VrP_2 | The bus I drive does not have all the necessary features to support safe and smooth passenger pick-up, drop-off, and running. | |

| SS | Supervisor support | [61,62] |

| SS_1 | My bus company is willing to invest money and effort to improve working conditions for bus drivers. | |

| SS_2 | My bus company seems to care about my health. | |

| SS_3 | My bus company seems to care about my safety. | |

| CS | Co-worker support | [61,63] |

| CS_1 | Bus drivers who I know expect me to work well. | |

| CS_2 | Bus drivers who I know are willing to listen to my working problems. | |

| CS_3 | I frequently get help and support from my co-workers. | |

| R | Rewards | [61,64] |

| R_1 | My performance is rewarded properly. | |

| R_2 | I receive the recognition I deserve for my the work I’ve done. | |

| TI | Turnover intention | [2,65,66] |

| TI_1 | I have a plan to stop my bus-driving occupation in a short time. | |

| TI_2 | I am currently thinking of stopping this occpupation. | |

| TI_3 | I have frequently thought about leaving this job for the last three months. |

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | ||

| Under 26 years old | 128 | 29.91% | |

| 26–45 years old | 227 | 53.04% | |

| Above 45 years old | 73 | 17.06% | |

| 2 | Educational degree | ||

| Not holding a university degree | 339 | 79.21% | |

| Holding a university degree | 89 | 20.79% | |

| 3 | Monthly income (million VND per month) | ||

| Below 15 | 281 | 65.65% | |

| At least 15 | 147 | 34.35% | |

| 4 | Driving experience | ||

| Below 2 years | 97 | 22.66% | |

| 2–5 years | 156 | 36.45% | |

| Above 5 years | 175 | 40.89% | |

| 5 | Route type | ||

| Urban route | 112 | 26.17% | |

| Non-urban route | 316 | 73.83% |

| Code | Pressure of Cabin and Vehicle | Pressure of Schedule | Pressure of Road and Traffic | Pressure of Weather | Organizational Support | Rewards | Turnover Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First run of EFA: For latent independent variables | |||||||

| CrP_1 | 0.7689 | ||||||

| CrP_2 | 0.7853 | ||||||

| RrP_1 | 0.8938 | ||||||

| RrP_2 | 0.8721 | ||||||

| RrP_3 | 0.8582 | ||||||

| WrP_1 | 0.7485 | ||||||

| WrP_2 | 0.8192 | ||||||

| SrP_1 | 0.9012 | ||||||

| SrP_2 | 0.8839 | ||||||

| SrP_3 | 0.8742 | ||||||

| SrP_4 | 0.9168 | ||||||

| SrP_5 | 0.8674 | ||||||

| VrP_1 | 0.8343 | ||||||

| VrP_2 | 0.7924 | ||||||

| SS_1 | 0.7382 | ||||||

| SS_2 | 0.8372 | ||||||

| SS_3 | 0.8213 | ||||||

| CS_1 | 0.7849 | ||||||

| CS_2 | 0.8138 | ||||||

| CS_3 | 0.8452 | ||||||

| R_1 | 0.9213 | ||||||

| R_2 | 0.9058 | ||||||

| Model parameters: Sample size: 428; Bartlett’s test of sphericity: p-value (0.000); Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy: 0.7654; method: principal component factors with eigenvalue > 1; rotation: orthogonal oblimin (Kaiser on); number of extracted factors: 4; variance explained: 0.6469 | |||||||

| Second run of EFA: For latent dependent variable (i.e., turnover intention) | |||||||

| TI_1 | 0.8927 | ||||||

| TI_2 | 0.8863 | ||||||

| TI_3 | 0.8659 | ||||||

| Model parameters: Sample size: 428; Bartlett’s test of sphericity: p-value (0.000); Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy: 0.8154; method: principal component factors with eigenvalue > 1; rotation: orthogonal oblimin (Kaiser on); number of extracted factors: 1; variance explained: 0.7142. | |||||||

| Factors | β | Std. Err. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | |||

| Under 26 years old (reference) | ||||

| 26–45 years old | Not significant | |||

| Above 45 years old | 0.337 | 0.089 | 0.000 | |

| 2 | Educational degree | |||

| Not holding a university degree (reference) | ||||

| Holding a university degree | Not significant | |||

| 3 | Monthly income (million VND permonth) | |||

| Below 15 (reference) | ||||

| At least 15 | Not significant | |||

| 4 | Driving experience | |||

| Below 2 years (reference) | ||||

| 2–5 years | Not significant | |||

| Above 5 years | 0.122 | 0.073 | 0.034 | |

| 5 | Route type | |||

| Urban route (reference) | ||||

| Non-urban route | −0.155 | 0.100 | 0.085 | |

| 5 | Pressure of cabin and vehicle | 0.189 | 0.031 | 0.004 |

| 6 | Pressure of schedule | 0.368 | 0.031 | 0.000 |

| 7 | Pressure of road and traffic | 0.329 | 0.032 | 0.000 |

| 8 | Pressure of weather | 0.147 | 0.032 | 0.010 |

| 9 | Organizational support | −0.125 | 0.031 | 0.009 |

| 10 | Rewards | −0.153 | 0.031 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ha, T.T. Predictors of Intention to Quit Among Urban Bus Drivers in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072850

Ha TT. Predictors of Intention to Quit Among Urban Bus Drivers in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Vietnam. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072850

Chicago/Turabian StyleHa, Thanh Tung. 2025. "Predictors of Intention to Quit Among Urban Bus Drivers in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Vietnam" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072850

APA StyleHa, T. T. (2025). Predictors of Intention to Quit Among Urban Bus Drivers in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Vietnam. Sustainability, 17(7), 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072850