Participatory Flood Risk Management and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Communication Engagement, Severity Beliefs, Mitigation Barriers, and Social Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background Literature and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Flood Information, Risk Severity, Mitigation Barriers, Information Seeking, and Risk Communication

2.2. Threat Appraisal, Risk Communication, and Efficacy Beliefs

2.3. Mitigation Barriers, Efficacy Beliefs, and Participatory Planning

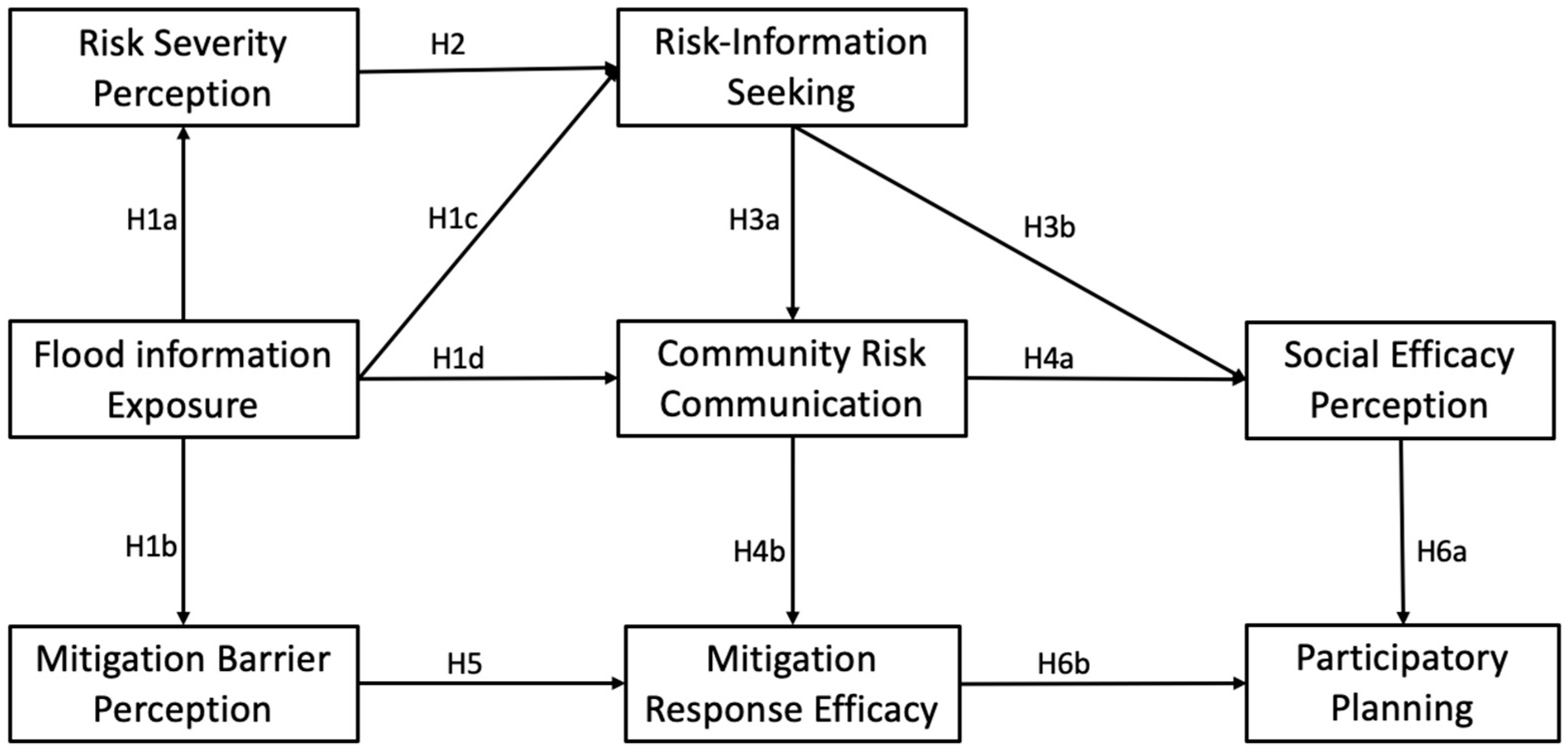

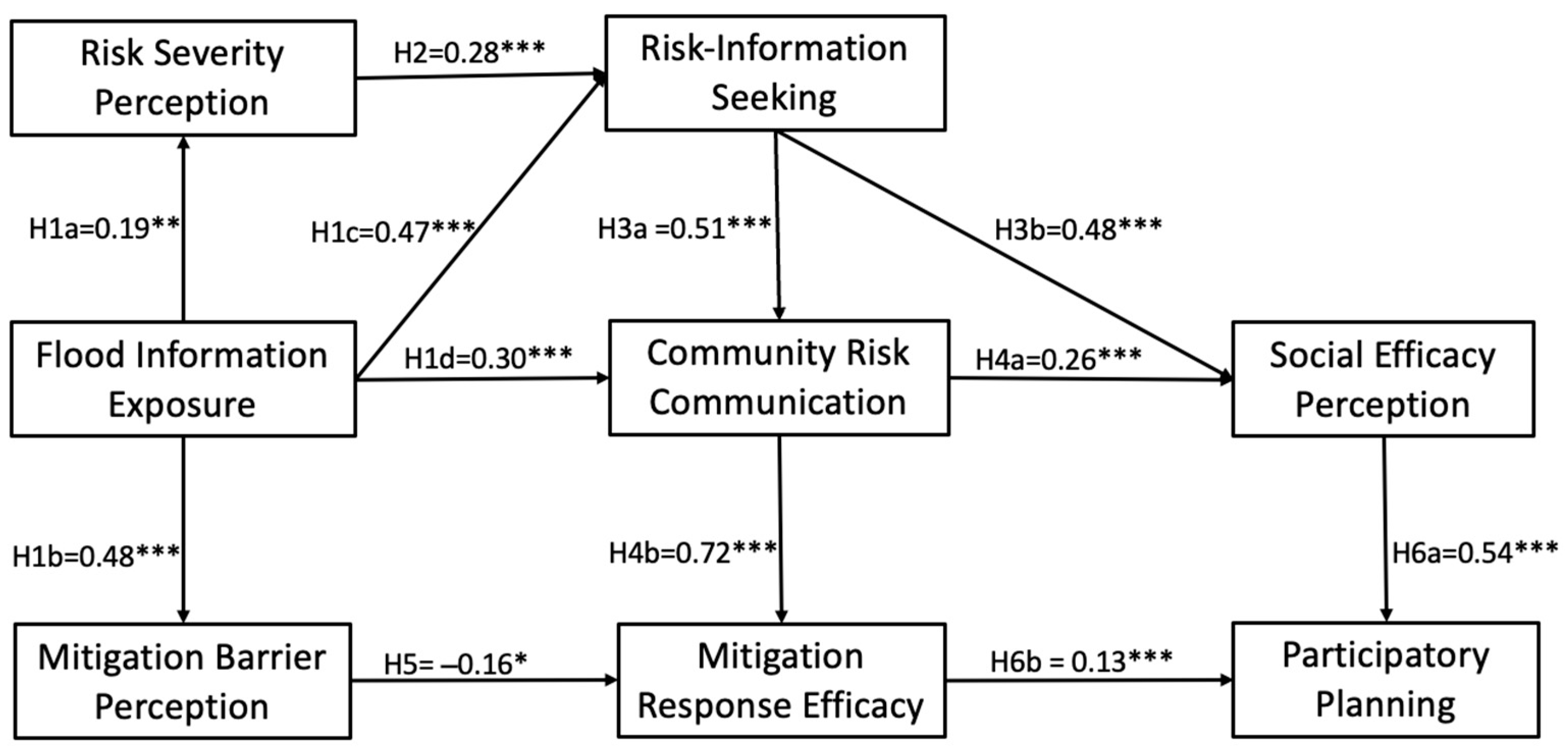

3. Proposed Conceptual Model

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Procedure

4.2. Data Analysis

4.3. Definitions

5. Results

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayo, T.L.; Lin, N. Climate Change Impacts to the Coastal Flood Hazard in the Northeastern United States. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 36, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelo, J.; Mayo, T. The Lasting Impacts of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale on Storm Surge Risk Communication: The Need for Multidisciplinary Research in Addressing a Multidisciplinary Challenge. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 33, 100335. [Google Scholar]

- Thiem, H. Extreme Rainfall Brings Catastrophic Flooding to the Northeast in August 2024. Climate.gov, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 30 August 2024. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/extreme-rainfall-brings-catastrophic-flooding-northeast-august-2024 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Tyler, J.; Sadiq, A.A.; Noonan, D.S.; Entress, R.M. Decision Making for Managing Community Flood Risks: Perspectives of United States Floodplain Managers. Intern. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 12, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.D.; Gunn, J.; Peacock, W.; Highfield, W.E. Examining the Influence of Development Patterns on Flood Damages Along the Gulf of Mexico. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, W.; Zaalberg, R.; De Maeyer, P. The Informed Society: An Analysis of the Public’s Information Seeking Behavior Regarding Coastal Flood Risks. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bubeck, P.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Laudan, J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Thieken, A.H. Insights into Flood-Coping Appraisals of Protection Motivation Theory: Empirical evidence from Germany and France. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social Learning Theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, R.; Vassileva, J.; Mandryk, R. Towards an Effective Health Interventions Design: An Extension of The Health Belief Model. Online J. Public Health Inform. 2012, 4, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. National Risk Index and Risk Communication, Fact Sheet. Federal Emergency Management Agency. March 2023. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_national-risk-index_risk-comms-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- NOAA. Risk Communication and Behavior: Best Practices and Research Finding, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2016. Available online: https://www.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-08/Natural_Hazard_Risk_Communication_Best_Practices.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Botzen, W.J.W.; Kunreuther, H.; Czajkowski, J.; de Moel, H. Adoption of Individual Flood Damage Mitigation Measures in New York City: An Extension of Protection Motivation Theory. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 2143–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, E.; Khanna, S.; Darychuk, A.; Copes, R.; Schwartz, B. Evidence Synthesis—Evaluating Risk Communication During Extreme Weather and Climate Change: A Scoping review. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2019, 39, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Babcicky, P.; Seebauer, A. Unpacking protection motivation theory: Evidence for a separate protective and non-protective route in private flood mitigation behavior. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 1503–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahieh, N.; Gilbert, M.; Sutton, J.; Shackelford, R. Deadly Storm Sends Water Levels Skyrocketing on Northeast Rivers and at The Coast, Forcing Evacuations. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/10/weather/winter-storm-snow-blizzard-forecast-wednesday/index.html (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- NOAA. Intense Storms in the Northeast Cause Catastrophic Flooding, National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 14 July 2024. Available online: https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news/intense-storms-the-northeast-cause-catastrophic-flooding (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Carpenter, C.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Health Belief Model Variables in Predicting Behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby-Straker, R.; Straker, L. The Effect of Experiencing Disaster Losses on Risk Perceptions and Preparedness Behaviors (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 8). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. 2023. Available online: https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/the-effect-of-experiencing-disaster-losses-on-risk-perceptions-and-preparedness-behaviors (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Morris, S.A.; Tippett, J. Perceptions and Practice in Natural Flood Management: Unpacking Differences in Community and Practitioner Perspectives. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 67, 2528–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikes, J.; Henstra, D.; Thistlethwaite, J. Public Attitudes Toward Policy Instruments for Flood Risk Management. Environ. Manag. 2023, 72, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, W.; Terpstra, T.; De Maeyer, P. Perception and Communication of Flood Risks: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.A. Developing Location-Based Communication and Public Engagement Strategies to Build Resilient Coastal Communities. 2019. Available online: https://circa.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1618/2019/10/Carolyn-Lin_CIRCA-Project-Report.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Seebauer, S.; Ortner, S.; Babcicky, P.; Thaler, T. Bottom-up Citizen Initiatives as Emergent Actors in Flood Risk Management: Mapping Roles, Relations and Limitations. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 12, e12468. [Google Scholar]

- Bohensky, E.L.; Leitch, A.M. Framing the Flood: A Media Analysis of Themes of Resilience in the 2011 Brisbane Flood. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, D.; Contreras, S.; Karlin, B.; Basolo, V.; Matthew, R.; Sanders, B.; Houston, D.; Cheung, W.; Goodrich, K.; Reyes, A.; et al. Communicating Flood Risk: Looking Back and Forward at Traditional and Social Media Outlets. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 15, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Jin, Y.; Austin, L.L. The Tendency to Tell: Understanding Publics’ Communicative Responses to Crisis Information form and Source. J. Public Relat. Res. 2013, 25, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, S.; Schultz, F.; Glocka, S. Crisis Communication Online: How Medium, Crisis Type and Emotions Affected Public Reactions in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster. Public Relat. Rev. 2013, 39, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Landwehr, P.M.; Wei, W.; Kowalchuck, M.; Carley, K.M. Using Tweets to Support Disaster Planning, Warning and Response. Saf. Sci. 2016, 90, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardi, S. Peer Coordination and Communication Following Disaster Warnings: An Experimental Framework. Saf. Sci. 2016, 90, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Box, P.; Bird, D.; Haynes, K.; King, D. Shared Responsibility and Social Vulnerability in the 2011 Brisbane Flood. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 1549–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Haer, T.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Aerts, J.C.H.H. The Effectiveness of Flood Risk Communication Strategies and The Influence of Social Networks—Insights from An Agent-Based Model. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 60, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebauer, S.; Babcicky, P. Trust and The Communication of Flood Risks: Comparing the Roles of Local Governments, Volunteers in Emergency Services, and Neighbours. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Brito, R.P.; de Souza Miguel, P.L.; Pereira, S.C.F. Climate Risk Perception and Media Framing. RAUSP Manag. J. 2020, 55, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B. Information Seeking in a Flood. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2013, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Altinay, Z.; Rittmeyer, E.; Morris, L.L.; Remas, M.A. Public Risk Salience of Sea Level Rise in Louisiana, United States. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M. Information Seeking and Sharing During a Flood: A Content Analysis of a Local Government’s Facebook Page. In European Conference on Social Media (ECSM 2014); Rospigliosi, A., Greener, S., Eds.; Academic Conferences Limited: Reading, UK, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Eachus, J.D.; Keim, B.D. A Survey for Weather Communicators: Twitter and Information Channel Preferences. Weather Clim. Soc. 2019, 11, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCarlo, M.F.; Berglund, E.Z. Use of Social Media to Seek and Provide Help in Hurricanes Florence and Michael. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1187–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, P.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Kreibich, H.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Detailed Insights into The Influence of Flood-Coping Appraisals on Mitigation Behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, R.; Wreford, A.; Butler, A.; Moran, D. The Impact of Flood Action Groups on the Uptake of Flood Management Measures. Clim. Change 2016, 138, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. The Role of Social Norms in Climate Adaptation: Mediating Risk Perception and Flood Insurance Purchase. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.; Skinner, C.S. The Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior and Health Education, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Inal, E.; Doganm, N. Improvement of General Disaster Preparedness Belief Scale Based on Health Belief Model. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2018, 33, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.; O’Malley, K.; Hynds, O.; O’Neill, E.; O’Dwyer, J. Assessment of Two Behavioural Models (HBM and RANAS) for Predicting Health Behaviours in Response to Environmental Threats: Surface Water Flooding as a Source of Groundwater Contamination and Subsequent Waterborne Infection in The Republic of Ireland. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laily, N.; Wulandari, A.; Anggraini, L.; IlhamMuddin, F. The Health Belief Model (HBM) Implementation to Flood Preparedness. Adv. Res. J. Multidiscip. Discov. 2021, 66, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhd Noor, M.T.; Kadir Shahar, H.; Baharudin, M.R.; Syed Ismail, S.N.; Abdul Manaf, R.; Md Said, S.; Ahmad, J.; Muthiah, S.G. Facing flood disaster: A cluster randomized trial assessing communities’ knowledge, skills and preparedness utilizing a health model intervention. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejeta, L.T.; Ardalan, A.; Paton, D. Application of Behavioral Theories to Disaster and Emergency Health Preparedness: A Systematic Review. PLoS Curr. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.J. Social Amplification of Risk in the Internet Environment. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karanikola, P.; Panagopoulos, T.; Tampakis, S.; Karantoni, M.I.; Tsantopoulos, G. Facing and Managing Natural Disasters in the Sporades Islands, Greece. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 14, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, D.; Ling, M.; Haynes, K. Flooding Facebook—The Use of Social Media During the Queensland and Victorian Floods. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2012, 27, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rainear, A.; Lin, C.A. Communication Factors Influencing Flood-Risk Mitigation, Motivation, And Intention Among College Students. Weather Clim. Soc. 2021, 13, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.A. Flood Risk Management via Risk Communication, Cognitive Appraisal, Collective Efficacy, and Community Action. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huurne, E.T.; Gutteling, J. Information Needs and Risk Perception as Predictors of Risk Information Seeking. J. Risk Res. 2008, 11, 847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra, T.; Zaalberg, R.; de Boer, J.; Botzen, W.J.W. You Have Been Framed! How Antecedents of Information Need Mediate the Effects of Risk Communication Messages. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B.; Srinivasan, S.; Villegas, J.; Matyas, C.; Kiousis, S. Predicting Information Seeking Regarding Hurricane Evacuation in the Destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.D.; Madison, T.P. Public Risk Perception Attitude and Information-Seeking Efficacy on Floods: A Formative Study for Disaster Preparation Campaigns and Policies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 592–601. [Google Scholar]

- Kievik, M.; Gutteling, J.M. Yes, we can: Motivate Dutch citizens to Engage in Self-Protective Behavior with Regard to Flood Risks. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A.M.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Relationships between Climate Change Perceptions and Climate Adaptation Actions: Policy Support, Information Seeking, and Behaviour. Clim. Change 2022, 171, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstra, D.; McIlroy-Young, B. Communicating Flood Risk: Best Practices and Recommendations for the Lake Champlain-Richelieu River Basin International Lake Champlain—Richelieu River Study. A White Paper to the International Joint Commission. March 2022. Available online: https://ijc.org/sites/default/files/WP_2_Flood-Risk-Communication_EN_031722.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Edelenbos, J.; Van Buuren, A.; Roth, D.; Winnubst, M. Stakeholder Initiatives in Flood Risk Management: Exploring the Role and Impact of Bottom-Up Initiatives in Three ‘Room for the River’ Projects in the Netherlands. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 60, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Babcicky, P.; Seebauer, S. Collective Efficacy and Natural Hazards: Differing Roles of Social Cohesion and Task-Specific Efficacy in Shaping Risk and Coping Beliefs. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, A.; Falcone, R. Flood Risk and Preventive Choices: A Framework for Studying Human Behaviors. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L.; Han, A. The Driving Effect of Experience: How Perceived Frequency of Floods and Feeling of Loss of Control Are Linked to Household-Level Adaptation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 112, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, W.; Roberts, T.; Brewer, G. Conceptualising Risk Communication Barriers to Household Flood Preparedness. Urban Gov. 2023, 3, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskrey, S.A.; Mount, N.J.; Thorne, C.R.; Dryden, I.L. Participatory modelling for stakeholder involvement in the development of flood risk management intervention options. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 82, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, K.; Filatova, T.; Need, A.; Bin, Q. Avoiding or Mitigating fFooding: Bottom-Up Drivers of Urban Resilience to Climate Change in the USA. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 59, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A. Evaluating the Usability and Usefulness of a Storm Preparedness and Risk Assessment Mobile App. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, K.; Bruggeman, A.; Giannakis, E.; Zoumides, C. Improving Public Participation Processes for the Floods Directive and Flood Awareness: Evidence from Cyprus. Water 2018, 10, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaalberg, R.; Midden, C.; Meijnders, A.; McCalley, T. Prevention, adaptation, and threat denial: Flooding protecexperiences in the Netherlands. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.R.; Grant, S.; Thomas, R.E. Testing the public’s response to receiving severe flood warnings using simulated cell broadcast. Nat. Hazards 2022, 112, 1611–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L. The Psychology of Self-Defense: Self-Affirmation Theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 38, 183–242. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, O.; Agrawal, M.; Rao, H.R. Community Intelligence and Social Media Services: A Rumor Theoretic Analysis of Tweets During Social Crisis. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 407–426. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Flood Information Exposure | -- | |||||||

| 2. Perceived Flood Risk Severity | 0.18 * | |||||||

| 3. Perceived Barriers for Flood Mitigation | 0.45 ** | 0.36 ** | ||||||

| 4. Flood Risk Information Seeking | 0.54 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.34 ** | |||||

| 5. Community-Engaged Risk Communication | 0.56 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.70 ** | ||||

| 6. Perceived Social Efficacy | 0.42 ** | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.41 ** | 0.47 ** | |||

| 7. Perceived Flood RiskMitigation Efficacy | 0.47 ** | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.37 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.54 ** | ||

| 8. Participatory Flood Risk Management | 0.40 ** | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.41 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.47 ** | -- |

| M | 3.43 | 3.30 | 3.39 | 3.43 | 3.41 | 3.63 | 3.89 | 3.46 |

| SD | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.70 |

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | β | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Flood Information Exposure | Flood risk Severity Perception | 0.19 | 2.98 | 0.03 |

| H1b | Flood Information Exposure | Mitigation Barrier Perception | 0.48 | 8.26 | <0.001 |

| H1c | Flood Information Exposure | Risk Information Seeking | 0.47 | 8.46 | <0.001 |

| H1d | Flood Information Exposure | Community Risk Communication | 0.30 | 5.42 | <0.001 |

| H2 | Flood Risk Severity Perception | Flood Risk Information Seeking | 0.28 | 5.37 | <0.001 |

| H3a | Flood Risk Information Seeking | Community Risk Communication | 0.51 | 9.72 | <0.001 |

| H3b | Flood Risk Information Seeking | Social Efficacy Perception | 0.48 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| H4a | Community Risk Communication | Social Efficacy Perception | 0.26 | 3.44 | <0.001 |

| H4b | Community Risk Communication | Perceived Mitigation Response Efficacy | 0.72 | 6.79 | <0.001 |

| H5 | Mitigation Barrier Perception | Perceived Mitigation Response Efficacy | −0.16 | −2.22 | 0.026 |

| H6a | Social Efficacy Perception | Participatory Flood Rsk Management | 0.54 | 9.57 | <0.001 |

| H6b | Perceived Mitigation Response Efficacy | Participatory Flood Risk Management | 0.14 | 2.05 | 0.041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.A. Participatory Flood Risk Management and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Communication Engagement, Severity Beliefs, Mitigation Barriers, and Social Efficacy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072844

Lin CA. Participatory Flood Risk Management and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Communication Engagement, Severity Beliefs, Mitigation Barriers, and Social Efficacy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072844

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Carolyn A. 2025. "Participatory Flood Risk Management and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Communication Engagement, Severity Beliefs, Mitigation Barriers, and Social Efficacy" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072844

APA StyleLin, C. A. (2025). Participatory Flood Risk Management and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Communication Engagement, Severity Beliefs, Mitigation Barriers, and Social Efficacy. Sustainability, 17(7), 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072844