FDI Spillovers and High-Quality Development of Enterprises—Evidence from Chinese Service Enterprises

Abstract

:1. Introduction

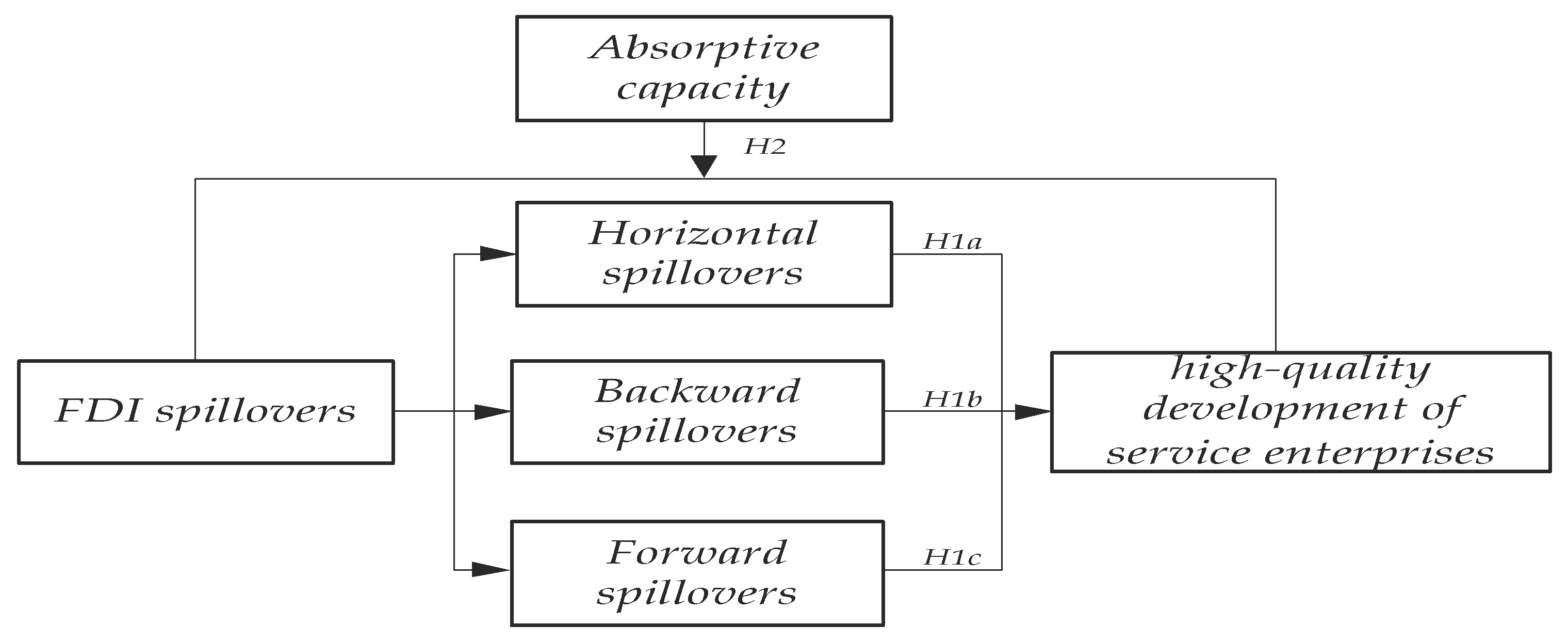

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. FDI Spillovers and the High-Quality Development of Service Enterprises

2.2. Threshold Effect of Enterprise Absorptive Capacity

3. Study Design

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Selection of Variables

3.2.1. Explained Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

- Horizontal spillovers (hs)

- 2.

- Vertical spillovers

3.2.3. Threshold Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Data Source and Descriptive Statistics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.2. Robustness Test

4.2.1. Replace the Explained Variable

4.2.2. Change the Sample Size

4.2.3. Endogenous Analysis

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Analysis Based on Different Geographical Locations

4.3.2. Analysis Based on Different Intensity of Factor Inputs

4.3.3. Analysis Based on Different Size

4.3.4. Analysis Based on Different Ownership

4.3.5. Analysis Based on Different Industry Classification

4.4. Test of Threshold Effect

5. Research Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, H.J.; Li, N.K.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, J.X. Informal board hierarchy and high-quality corporate development: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Han, Z.X.; Guo, M.W. FDI, new development philosophy and China’s high-quality economic development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 25227–25255. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.J.; Xiao, H.J.; Wang, X. Study on high-quality development of the state-owned enterprises. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 10, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.J.; Wen, J.Y.; Wang, X.H. Digital finance and high-quality development of state-owned enterprises—A financing constraints perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.L.; Xiao, F. Has climate change promoted the high-quality development of financial enterprises? Evidence from China. Front. Enviromental Sci. 2024, 12, 1332748. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.W.; Wang, D.Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, J. Equity reform and high-quality development of state-owned enterprises: Evidence from China in the new era. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 913672. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Yang, J.X.; Zhang, W.Q.; Zhou, Z.; Cong, J.H. Does high-speed railway promote high-quality development of enterprises ? Evidence from China’s listed companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, X. Productivity spillovers from R&D, exports and FDI in China’s manufacturing sector. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 544–557. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Liu, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.F. Do Chinese domestic firms benefit from FDI inflow? Evidence of horizontal and vertical spillovers. China Econ. Rev. 2009, 20, 677–691. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.P.; Sheng, Y. Productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment: Firm-level evidence from China. World Dev. 2012, 40, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Hou, K.Q. FDI technology spillovers in Chinese supplier-customer networks. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 94, 103285. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Tao, Z.G.; Zhu, L.M. Identifying FDI spillovers. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 107, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.; Park, B.I.; Ghauri, P.N. Foreign direct investment spillover effects in China: Are they different across industries with different technological levels? China Econ. Rev. 2013, 26, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Doytch, N.; Uctum, M. Spillovers from foreign direct investment in services: Evidence at sub-sectoral level for the Asia-Pacific. J. Asian Econ. 2019, 60, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.Y.; Liu, H. The spillover effect of foreign direct investment on independent innovation in China’s service industry: A threshold test based on the level of absorption. J. Commer. Econ. 2023, 16, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, H.; Read, R.; Elkomy, S. Aggregate and heterogeneous sectoral growth effects of foreign direct investment in Egypt. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2020, 24, 1511–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiharti, L.; Yasin, M.Z.; Purwono, R.; Esquivias, M.A.; Pane, D. The FDI spillover effect on the efficiency and productivity of manufacturing firms: Its implication on open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, V.T.C.; Holmes, M.J.; Hassan, G. Does foreign investment improve domestic firm productivity? Evidence from a developing country. J. Asia Pacific Econ. 2021, 28, 527–557. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Chen, Y.M.; Sun, B.S. The influence of international knowledge spillover on innovation output of Chinese industrial enterprises: Regulatory role of FDI channel, import trade channel, and absorption capacity. West Forum 2020, 30, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda, F.; Pérez-Hernández, F. Absorptive capacity and geographical distance two mediating factors of FDI spillovers: A threshold regression analysis for Spanish firms. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2017, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Paola, C.; Rajneesh, N. A novel approach to national technological accumulation and absorptive capacity: Aggregating Cohen and Levinthal. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2008, 20, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.N.; Wang, T.C. The impact of digital economy on the high quality development of agricultural enterprises: Evidence from listed agricultural enterprises in China. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241257358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Si, F.J.; Lei, P.F. Research on the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise high-quality development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, H.H.; Luo, R.Y.; Yu, Y.B. How digital transformation helps enterprises achieve high-quality development? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 2753–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.Z. Digitalization, green transformation, and the high-quality development of Chinese tourism enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Xiao, X.; Li, Z.Z.; Dai, Q.H. Does ESG performance promote high-quality development of enterprises in China? The mediating role of innovation input. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannek, M.; Zhang, Z.L.; Yanick, O.A.R.; Paulin, B. Entrepreneurship and high-quality development of enterprises—Empirical research based on Chinese listed companies. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 20718–20744. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Jiang, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y. Corporate social responsibility and high-quality development: Do green innovation, environmental investment and corporate governance matter? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 3191–3214. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.X.; Hu, H.Q.; Xue, M. Corporate risk-taking, innovation efficiency, and high-quality development: Evidence from Chinese firms. Systems 2024, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Lu, Y.L.; Huang, R.T. Whether foreign direct investment can promote high-quality economic development under environmental regulation: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21674–21683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N.; Merih, U. Does the worldwide shift of FDI from manufacturing to services accelerate economic growth? A GMM estimation study. J. Int. Money Financ. 2011, 30, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, X.Y. China’s import structure of services intermediate input and industrial growth effect. Econ. Surv. 2017, 34, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.H.; Lu, C.H. Service liberalization promotes transformation of trade modes—Firm-level theory and evidence from China. China Ind. Econ. 2020, 7, 156–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jude, C. Technology spillovers from FDI. Evidence on the intensity of different spillover channels. World Econ. 2015, 39, 1947–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, P.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, K.M. FDI spillover effect on the green productivity of Vietnam manufacturing firms: The role of absorptive capacity. J. Appl. Econ. 2024, 27, 2382653. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.C.; Vonortas, N.S. TFP, ICT and absorptive capacities: Micro-level evidence from Colombia. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 1287–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Smith, R.B.W.; Wu, L. ping. The impacts of foreign direct investment on total factor productivity: An empirical study of agricultural enterprises. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2024, 16, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, V.H.; Vinh, T.P. Spillover effects of Japanese firms and the role of absorptive capacity in Vietnam. Asia. Pac. Econ. Lit. 2024, 38, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, H.D. The threshold of absorptive capacity: The case of Vietnamese manufacturing firms. Int. Econ. 2020, 163, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Girma, S. Absorptive capacity and productivity spillovers from FDI: A threshold regression analysis. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2005, 67, 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Moralles, H.F.; Moreno, R. FDI productivity spillovers and absorptive capacity in Brazilian firms: A threshold regression analysis. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 70, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Ning, L.; Chen, K. How do human capital and R&D structure facilitate FDI knowledge spillovers to local firm innovation? A panel threshold approach. J. Technol. Transf. 2022, 47, 1921–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Orlic, E.; Hashi, I.; Hisarciklilar, M. Cross sectoral FDI spillovers and their impact on manufacturing productivity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Levinsohn, J.; Petrin, A. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demena, B.A.; Murshed, S.M. Transmission channels matter: Identifying spillovers from FDI. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2018, 27, 701–728. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.X.; Zhu, G.L. A Study on absorptive capacity’s meditative effect in the innovation process—Based on empirical evidence of South China. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2009, 30, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L.M.; Tang, Q.Q. The effect of technology acquisition on corporate performance and its intermediary factors—An empirical study based on China’s listed companies. Manag. Rev. 2010, 22, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marcin, K. How does FDI inflow affect productivity of domestic firms? The role of horizontal and vertical spillovers, absorptive capacity and competition. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2008, 17, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, V.; Holmes, M.J.; Hassan, G. Does foreign investment benefit the exporting activities of Vietnamese firms? World Econ. 2020, 43, 1619–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Miozzo, M.; Grimshaw, D. Service multinationals and forward linkages with client firms: The case of IT outsourcing in Argentina and Brazil. Int. Bus. Rev. 2008, 17, 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Javorcik, B.S. Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 605–627. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.L.; Xie, J.G.; Zhang, E.Z. FDI intensity and the competitiveness of local firms—An empirical research from the unit labor cost perspective. J. Int. Trade 2020, 2, 103293. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.H.; Yu, F.; Wang, X.Y. Could the Chinese service firms promote their innovation performance from the FDI in service industry?—Empirical evidence from survey data of service firms in 2008 and patent micro-data. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. Sci. 2018, 3, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.P.; Chen, H.B. The multiplier effect of foreign capital introduction on the employment of producer services. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2018, 39, 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Z.; Liu, J. FDI knowledge spillover, absorptive capacity and innovation output of high-tech industries—An empirical analysis based on threshold effect model. Technol. Innov. Manag. 2022, 43, 649–660. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, K.J.; Li, X.J.; Cui, X. Productive input imports and total factor productivity: Horizontal effect and vertical spillover. J. Int. Trade 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Q.L.; Xu, J.Y. How does foreign entry affect domestic value-added of local firms’ exports? China Econ. Q. 2018, 17, 1453–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Qian, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.H. Promotion effect of FDI on enterprise survival in host country—A discussion on industry safety and market access of foreign investment. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 7, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

| 1st-Level Indicators | 2nd-Level Indicators | 3rd-Level Indicators | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorptive capacity of the enterprise | Acquisition capacity | Degree of diversification | Herfindahl index |

| Degree of services concentration in the province where the enterprise is located | Employment in the service sector in the province where the enterprise is located/national employment in the service sector | ||

| Assimilation capacity | Level of human capital | Average employee salary | |

| Internal management efficiency | The ratio of administrative expenses to operating revenue | ||

| Transformation and integration capacity | Technological gap | TFP of the enterprise/maximum TFP of enterprises in the sector | |

| R&D level | The proportion of intangible assets in the total assets of the enterprise |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | High-quality development of enterprises | TFP | The logarithm of total factor productivity calculated by the LP method |

| Explanatory Variables | Horizontal spillovers | hs | The proportion of the main business revenue of MNC to the total main business revenue of the industry |

| Forward spillovers | fs | The proportion of the input purchased from upstream foreign firms to the total input of the sector | |

| Backward spillovers | bs | The proportion of the output sold to downstream foreign firms to the total output of the sector | |

| Threshold Variable | Absorptive capacity of the enterprise | absorb | See Table 1 |

| Control variables | Enterprise age | age | ln(year of observation-year of establishment + 1) |

| Enterprise capital intensity | kl | net book value of fixed assets/the number of employees | |

| Return on assets | roa | Net profit/total assets | |

| Enterprise profitability | profit | Net profit/total operating revenue | |

| Asset-to-liability ratio | debt | Total liabilities/total assets | |

| Degree of market competition | hhi | Herfindahl index of the two-digit industry |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | 4280 | 9.3284 | 1.2793 | 4.4579 | 13.5152 |

| hs | 4280 | 0.0480 | 0.0455 | 0.0002 | 0.2021 |

| fs | 4280 | 0.0280 | 0.0167 | 0.0050 | 0.0749 |

| bs | 4280 | 0.0167 | 0.0140 | 3.88 × 10−6 | 0.0706 |

| age | 4280 | 2.9742 | 0.2919 | 1.0986 | 3.9890 |

| absorb | 4280 | 1.01× 10−10 | 0.5816 | −1.6190 | 7.8580 |

| kl | 4280 | 0.0090 | 0.0825 | 0.00003 | 3.0448 |

| roa | 4280 | 0.0383 | 0.0721 | −0.5637 | 1.8525 |

| profit | 4280 | 0.1310 | 2.2924 | −15.7422 | 109.7486 |

| debt | 4280 | 0.4613 | 0.2491 | 0.0103 | 8.2564 |

| hhi | 4280 | 0.1716 | 0.1981 | 0 | 1 |

| Variables | (1) TFP | (2) TFP |

|---|---|---|

| hs | 0.8668 *** (2.83) | 0.9026 *** (2.94) |

| bs | 5.4052 *** (2.93) | 5.3563 *** (2.98) |

| fs | −4.8030 *** (−3.33) | −4.9436 *** (−3.51) |

| age | 0.7056 *** (3.00) | |

| roa | 1.3529 *** (4.55) | |

| kl | 0.4926 *** (5.30) | |

| profit | −0.0322 *** (−4.09) | |

| hhi | −0.0523 (−0.38) | |

| debt | 0.4617 (1.28) | |

| Constant | 9.3309 *** (256.98) | 6.9792 *** (10.96) |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Observations | 4280 | 4280 |

| R-squared | 0.8652 | 0.8709 |

| Variables | Replace the Explained Variable | Change the Sample Size | IV1 | IV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TFP(ACF) | (2) TFP | (3) TFP | (4) TFP | |

| hs | 0.7913 *** (2.77) | 0.7558 ** (1.99) | 2.0416 ** (2.12) | 1.3300 *** (3.58) |

| bs | 4.4478 *** (2.59) | 5.8330 *** (2.60) | 8.6059 *** (4.33) | 6.3762 *** (3.51) |

| fs | −3.6115 *** (−2.67) | −4.8928 *** (−2.81) | −3.7550 *** (−3.95) | −3.0570 *** (−3.18) |

| age | 0.5715 *** (2.78) | 0.8038 *** (2.95) | 1.9414 *** (11.42) | 2.0322 *** (24.64) |

| roa | 1.1129 *** (4.46) | 1.2821 *** (3.74) | 1.8292 *** (7.41) | 1.3890 *** (4.65) |

| kl | 0.9923 *** (4.82) | 0.4308 *** (4.34) | 0.4547 *** (5.16) | 0.5489 *** (5.37) |

| profit | −0.0286 *** (−4.00) | −0.0300 *** (−3.92) | −0.0281 *** (−4.44) | −0.0332 *** (−4.16) |

| hhi | 0.1763 (1.32) | −0.1762 (−1.03) | −0.1828 (−1.35) | −0.0530 (−0.38) |

| debt | 0.4728 * (1.70) | 0.3592 (1.04) | 1.3024 *** (8.08) | 0.4307 (1.26) |

| Constant | 5.8186 *** (10.16) | 6.6727 *** (8.73) | ||

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 4280 | 3056 | 3745 | 4280 |

| LM statistic | 514.987 [0.00] | 193.551 [0.00] | ||

| Wald F statistic | 270.298 [16.38] | 881.962 [16.38] | ||

| R-squared | 0.8669 | 0.8564 | 0.2828 | 0.2701 |

| Variables | Eastern Region | Central and Western Regions | Capital-Intensive | Labor-Intensive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TFP | (2) TFP | (3) TFP | (4) TFP | |

| hs | 1.0645 *** (3.25) | −0.1972 (−0.28) | 0.9670 ** (2.23) | 0.0949 (0.24) |

| bs | 3.5982 *** (2.01) | 14.1987 ** (2.38) | 3.7037 * (1.72) | 2.5709 (1.06) |

| fs | −4.9552 *** (−3.21) | −5.8049 * (−1.72) | −4.0623 ** (−2.44) | −2.4709 (−1.12) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 6.0470 *** (7.65) | 8.2521 *** (8.28) | 8.4925 *** (10.44) | 6.9246 *** (7.23) |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 3264 | 1016 | 2140 | 2140 |

| R-squared | 0.8791 | 0.8611 | 0.9140 | 0.8996 |

| Variables | Large-Scale | SMEs | SOEs | Non-SOEs | Producer Services | Consumer Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TFP | (2) TFP | (3) TFP | (4) TFP | (5) TFP | (6) TFP | |

| hs | −0.1501 (−0.41) | 1.0320 *** (2.58) | −0.2919 (−0.67) | 0.0149 (0.04) | 0.9039 *** (2.76) | 1.0893 (0.33) |

| bs | 2.3768 (1.27) | 4.7424 **(2.08) | 3.9298 (1.57) | 4.4539 * (1.77) | 6.0792 *** (3.20) | −3.3653 (−0.32) |

| fs | −1.6855 (−1.12) | −5.7320 *** (−2.83) | −3.1428 * (−1.73) | −3.8143 (−1.57) | −5.3794 *** (−3.41) | −8.6322 (−0.68) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 10.2158 *** (14.90) | 4.7316 *** (5.93) | 8.8284 *** (14.37) | 6.9907 *** (6.22) | 7.1798 *** (10.45) | 7.0510 *** (5.13) |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2140 | 2140 | 2040 | 2240 | 3808 | 472 |

| R-squared | 0.9066 | 0.8374 | 0.8766 | 0. 8653 | 0.8748 | 0.7926 |

| Key Explanatory Variables | Model | F-Value | p-Value | Critical Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | ||||

| hs | Single threshold | 425.53 | 0.0000 | 34.6619 | 25.4778 | 21.4294 |

| Double threshold | 97.13 | 0.0000 | 26.7032 | 21.3751 | 18.7991 | |

| Triple threshold | 60.95 | 0.5533 | 136.0193 | 113.9588 | 103.6602 | |

| bs | Single threshold | 499.16 | 0.0000 | 26.2645 | 17.8501 | 15.2914 |

| Double threshold | 156.09 | 0.0000 | 23.5636 | 16.5947 | 14.5885 | |

| Triple threshold | 129.10 | 0.5100 | 213.0167 | 183.5319 | 168.3923 | |

| fs | Single threshold | 578.28 | 0.0000 | 20.1771 | 15.3502 | 13.4104 |

| Double threshold | 189.62 | 0.0000 | 23.7336 | 16.1647 | 13.6488 | |

| Triple threshold | 115.45 | 0.5233 | 207.9393 | 176.2673 | 159.5902 | |

| Key Explanatory Variables | Model | Threshold Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| hs | Single threshold | −0.6449 | [−0.6666, −0.6135] |

| Double threshold | −0.3659 | [−0.3815, −0.3469] | |

| −0.2976 | [−0.3198, −0.2512] | ||

| bs | Single threshold | −0.4371 | [−0.4979, −0.4252] |

| Double threshold | −0.4371 | [−0.4542, −0.4252] | |

| −0.0742 | [−0.0846, −0.0639] | ||

| fs | Single threshold | −0.5127 | [−0.5342, −0.4979] |

| Double threshold | −0.4371 | [−0.4542, −0.4252] | |

| −0.0639 | [−0.0914, −0.0535] |

| Variables | (1) TFP | (2) TFP | (3) TFP |

|---|---|---|---|

| hs | 1.1188 *** (3.10) | 1.0024 *** (2.81) | |

| bs | 4.5777 *** (3.81) | 7.0427 *** (4.28) | |

| fs | −2.3747 *** (−3.75) | −2.8002 *** (−3.44) | |

| age | 1.8830 *** (15.48) | 1.8159 *** (15.48) | 1.8074 *** (15.92) |

| roa | 1.1775 *** (4.67) | 1.1667 *** (4.81) | 1.0889 *** (4.63) |

| kl | 0.5829 *** (11.91) | 0.5017 *** (9.12) | 0.5302 *** (11.38) |

| profit | −0.0275 *** (−3.15) | −0.0293 *** (−4.92) | −0.0271 *** (−5.66) |

| hhi | −0.0252 (−0.12) | −0.1367 (−0.66) | −0.0399 (−0.20) |

| debt | 0.4126 (1.18) | 0.3964 (1.18) | 0.3882 (1.22) |

| constant | 3.4222 *** (9.02) | 3.6652 *** (10.05) | 3.6991 *** (10.43) |

| −6.1414 *** (−6.64) | −17.6126 *** (−6.41) | −24.0107 *** (−10.83) | |

| −1.3181 ** (−2.48) | 2.6094 (1.36) | −6.8863 *** (−6.22) | |

| 4.0548 *** (9.02) | 15.2902 *** (7.02) | 2.9882 *** (3.14) | |

| R-squared | 0.1559 | 0.1960 | 0.2155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, P.; Xu, H. FDI Spillovers and High-Quality Development of Enterprises—Evidence from Chinese Service Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072806

Meng P, Xu H. FDI Spillovers and High-Quality Development of Enterprises—Evidence from Chinese Service Enterprises. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072806

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Pei, and Hongyi Xu. 2025. "FDI Spillovers and High-Quality Development of Enterprises—Evidence from Chinese Service Enterprises" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072806

APA StyleMeng, P., & Xu, H. (2025). FDI Spillovers and High-Quality Development of Enterprises—Evidence from Chinese Service Enterprises. Sustainability, 17(7), 2806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072806