ESG Performance of Chinese Listed Enterprises Participating in the Belt and Road Initiative

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Interaction Between the BRI and ESG

2.2. Multiple Mechanisms of the BRI

2.3. Different Characteristics of Enterprises

3. Data

3.1. Data Sources and Filtering

- It is the only ESG ratings system in China with data traced back to before 2013 (namely, before the BRI was proposed);

- It covers all A-share listed enterprises and therefore avoids self-selection bias and has strong representativeness;

- Instead of relying on self-reported data from enterprises, it proactively collects over 300 indicators for ratings, avoiding greenwashing behaviour;

- It takes into account industry heterogeneity in ratings, making it unnecessary to consider industry factors in this paper.

- Remove samples with missing or incomplete data;

- Remove samples from the financial industry;

- Remove samples with special treatment (ST and *ST stocks) in the risk alert board.

3.2. Variables

4. Methodology

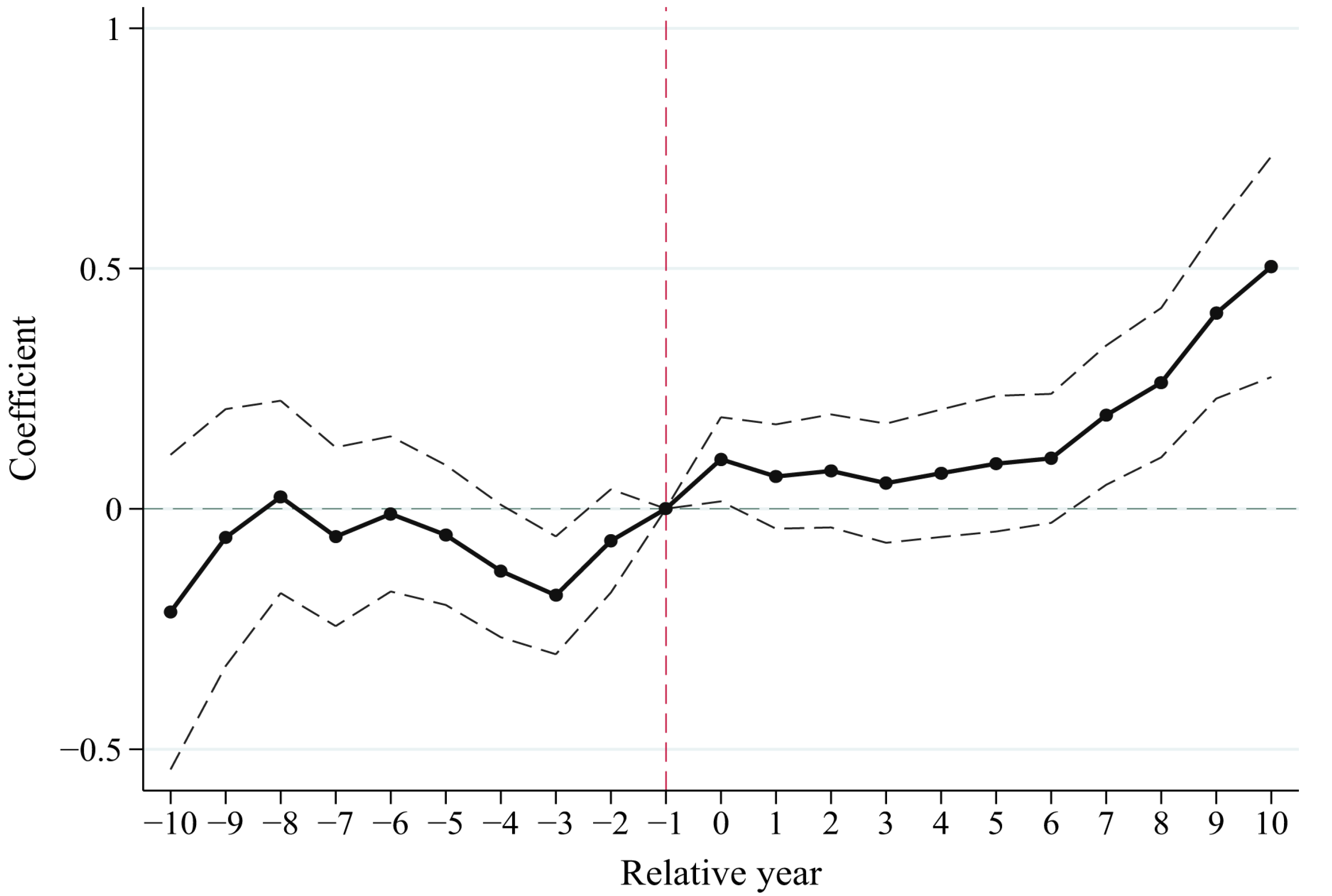

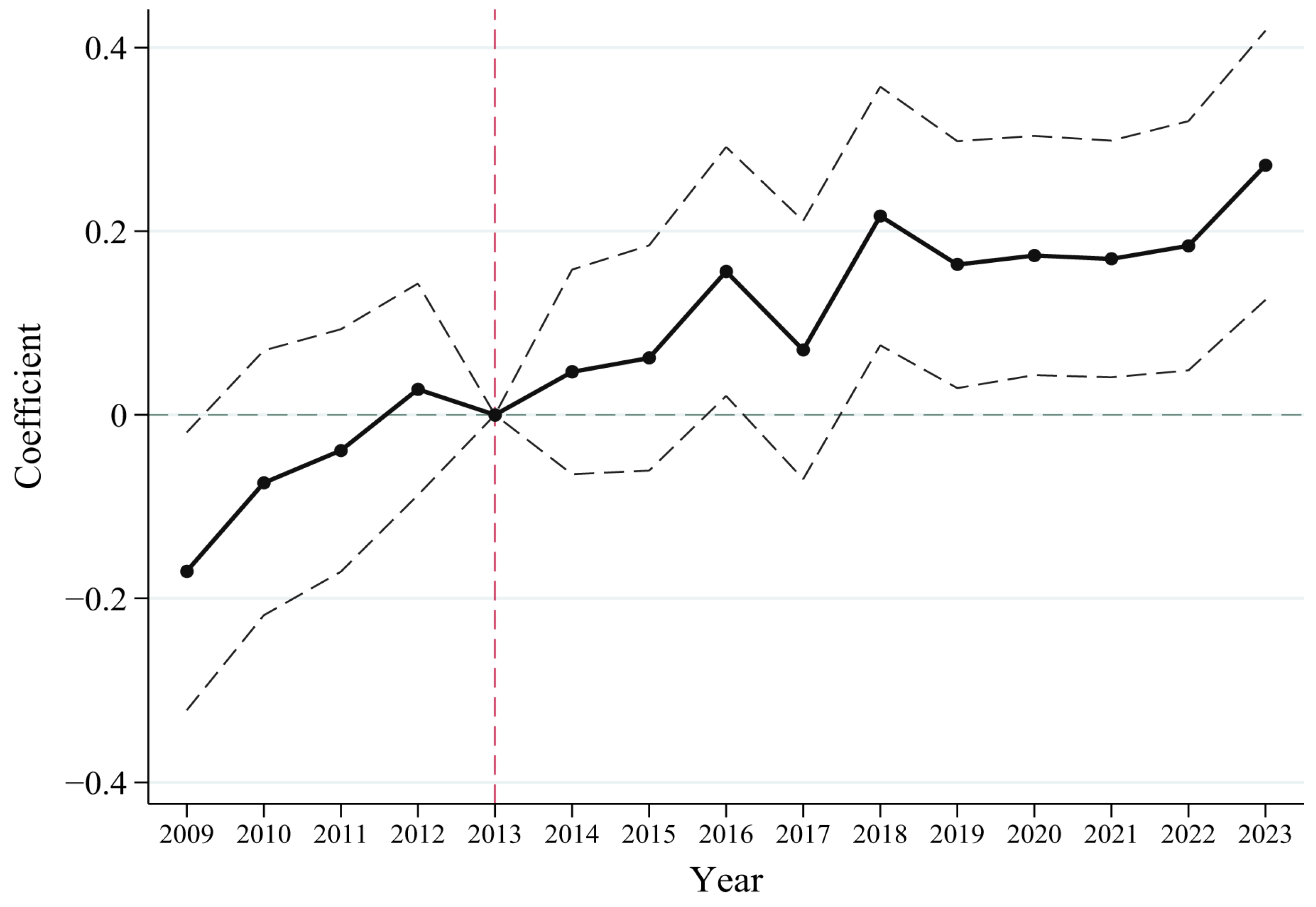

4.1. Standard DID Model

4.2. Time-Varying DID Model

4.3. Triple-Difference Model

5. Results

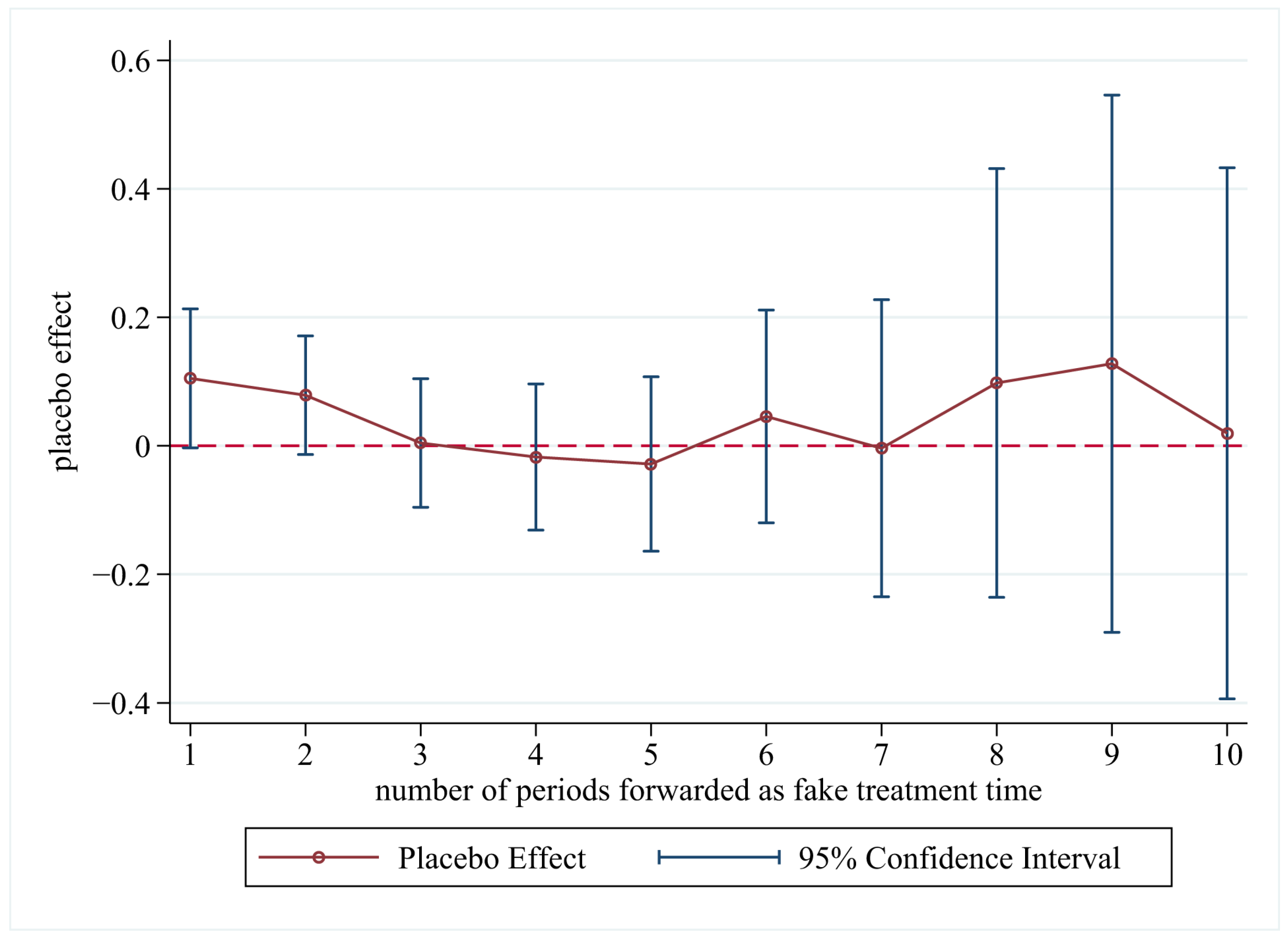

5.1. Principal Results

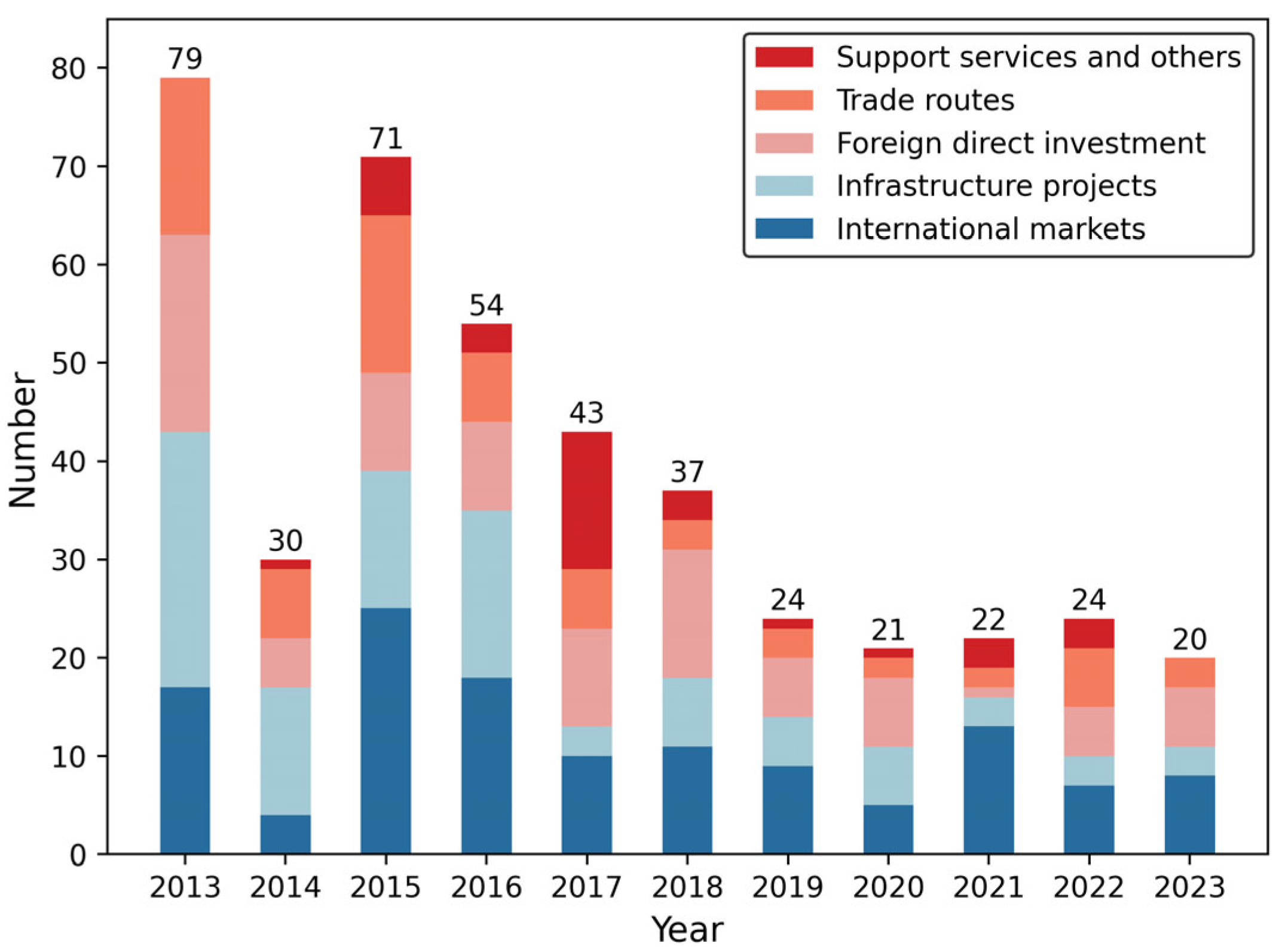

5.2. Mechanism Analysis

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| BRI | Belt and Road Initiative |

| SOEs | State-owned enterprises |

| DID | Difference in differences |

| DDD | Triple difference |

| OFDI | Outward foreign direct investment |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| PTA | Parallel trends assumption |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time ≥ 2013 | Time ≥ 2014 | Time ≥ 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Treat × Time | 0.216 *** (0.048) | 0.192 *** (0.048) | 0.216 *** (0.045) | 0.194 *** (0.045) | 0.212 *** (0.043) | 0.189 *** (0.042) |

| Constant | 4.123 *** (0.004) | 0.067 (0.433) | 4.124 *** (0.003) | 0.069 (0.433) | 4.126 *** (0.003) | 0.071 (0.433) |

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 43,484 | 43,484 | 43,484 | 43,484 | 43,484 | 43,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.3883 | 0.4071 | 0.3884 | 0.4073 | 0.3885 | 0.4073 |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time-Varying PSM-DID | Standard PSM-DID | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥2013 | ≥2014 | ≥2015 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| BRI | 0.179 *** (0.040) | |||

| Treat × Time | 0.185 *** (0.048) | 0.184 *** (0.045) | 0.179 *** (0.043) | |

| Constant | 0.030 (0.438) | 0.032 (0.438) | 0.030 (0.438) | 0.030 (0.438) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 42,494 | 42,494 | 42,494 | 42,494 |

| Adj R2 | 0.4086 | 0.4084 | 0.4085 | 0.4086 |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time-Varying DID | Standard DID | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted to 2010–2023 (Avoiding Disruptions from an Ex-Ante Trend in 2009) | Restricted to 2010–2018 (Further Avoiding Disruptions from COVID-19) | Restricted to 2010–2023 (Time ≥ 2013) | Placebo Test (Time = 0 if 2010–2011; Time = 1 if 2012–2013) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| BRI | 0.165 *** (0.040) | 0.197 *** (0.050) | ||

| Treat×Time | 0.164 *** (0.049) | 0.072 (0.051) | ||

| Constant | −0.071 (0.452) | 1.588 ** (0.674) | −0.078 (0.452) | −0.283 (1.398) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 42,117 | 21,303 | 42,117 | 7906 |

| Adj R2 | 0.4119 | 0.5031 | 0.4117 | 0.5376 |

Appendix C

References

- State Council of China. The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future. Available online: http://english.scio.gov.cn/whitepapers/2023-10/10/content_116735061.htm (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- United Nations. Progress Report on the Belt and Road Initiative in Support of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/progress_report_bri-sdgs_english-final.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Maliszewska, M.; van der Mensbrugghe, D. The Belt and Road Initiative: Economic, Poverty and Environmental Impacts; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8814; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, P.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Qin, M. The Belt and Road Initiative, public health expenditure and economic growth: Evidence from quasi-natural experiments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Chen, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Does the BRI contribute to poverty reduction in countries along the Belt and Road? A DID-based empirical test. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.; Hussain, M.N.; Ilyas, M. An impact evaluation of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) on environmental degradation. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221078836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Cai, X.; Liu, B. The Belt and Road Initiative and ESG performance of the enterprises. Int. Econ. Trade Res. 2024, 40, 58–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Sun, J.; Huang, G.; Su, C.Y. Environmental, social and governance performance of Chinese multinationals: A comparison of state-and non-state-owned enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Xu, A.; Wang, S.; Jia, X.; Liao, Z.; Tan, R.R.; Sun, H.; Su, F. Progress towards sustainable development goals in the Belt and Road Initiative countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.J.; Yang, X.; Moise, D.; Roddy, S.J. Dynamic synergies between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the UN’s sustainable development goals. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2021, 4, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Fan, X.; Shuai, C.; Yu, X.; Tan, Y. Impacts and pathways of the Belt and Road Initiative on sustainable development goals of the involved countries. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2976–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydyrbek, F.; Hor, K.W.C.; Baikushikova, G.; Kukeyeva, F.; Augan, M. Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative and SDG 7 from an international relations perspective: The case of Kazakhstan. China WTO Rev. 2024, 10, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Senadjki, A.; Bashir, M.J.; AuYong, H.N.; Awal, I.M.; Chan, J.H. Pathways to sustainability: How China’s Belt and Road Initiative is shaping responsible production and consumption in Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 1468–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnett, E.; Coulibaly, A.; Hulse, D.; Hoctor, T.; Ahmad, B.; An, L.; Lewison, R. Corporate responsibility and biodiversity conservation: Challenges and opportunities for companies participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 49, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Noronha, C.; Guan, J. CSR Reporting and the Belt and Road Initiative: Implementation by Chinese Multinational Enterprises, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, L. Home-country institutions and corporate social responsibility of emerging economy multinational enterprises: The Belt and Road Initiative as an example. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2022, 39, 927–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S.; Ying, R. Peer effects, environmental regulation and environmental financial integration—Empirical evidence from listed companies in heavily polluting industries. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 82, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Sun, M. Government subsidies and corporate environmental, social and governance performance: Evidence from companies of China. Int. Stud. Econ. 2024, 19, 374–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Han, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W. ESG performance, institutional investors’ preference and financing constraints: Empirical evidence from China. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.L.; Desroziers, A.; Caccioli, F.; Aste, T. ESG reputation risk matters: An event study based on social media data. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, Z. Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on enterprise green transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. The impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on green innovation and innovation modes: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1323888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Feng, G.F.; Chang, C.P. How does ESG performance promote corporate green innovation? Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 2889–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ivashkovskaya, I.; Besstremyannaya, G.; Liu, C. Unlocking green innovation potential amidst digital transformation challenges—The evidence from ESG transformation in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, T.T. Chinese firms ‘going global’: Recent OFDI trends, policy support and international implications. Int. Politics 2015, 52, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Shen, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Lee, C.C. What is the rationale behind China’s infrastructure investment under the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Econ. Surv. 2022, 36, 605–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, C. Does “Going Global” help to restrain enterprises’ financialization: The Belt and Road initiative as a quasi-natural experiment. China Econ. Q. Int. 2024, 4, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jigeer, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H. China-Russia cooperation in the Northern Sea Route development. Int. Organ. Res. J. 2025, 20, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.S. The current status and challenges of China Railway Express (CRE) as a key sustainability policy component of the Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görg, H.; Mao, H. Does the Belt and Road Initiative stimulate Chinese exports? Evidence from micro data. World Econ. 2022, 45, 2084–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, J. Beyond ports, roads and railways: Chinese economic statecraft, the Belt and Road Initiative and the politics of financial infrastructures. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2023, 29, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wu, W. Environment, social, and governance performance and corporate financing constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Tam, C.M. From voluntarism to regulation: A study on ownership, economic performance and corporate environmental information disclosure in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Hao, X.; Zhang, X. The ESG rating, spillover of ESG ratings, and stock return: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 80, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.E.; Pentescu, A.; Shivarov, A. Sustainability, ESG ratings and corporate performance in the manufacturing sector: A research review. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 15, 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, H. Manufacturing enterprises move towards sustainable development: ESG performance, market-based environmental regulation, and green technological innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Cheng, X. Can ESG indices improve the enterprises’ stock market performance?—An empirical study from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Luo, L.; Sun, H.; Zhong, Q. Does going abroad lead to going green? Firm outward foreign direct investment and domestic environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.F. Discovering the evolution of Pollution Haven Hypothesis: A literature review and future research agenda. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48210–48232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y.H.; Chen, X.Z. ESG performance and business risk—Empirical evidence from China’s listed companies. Innov. Green Dev. 2024, 3, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Bae, J.; Kim, H. The effect of corporate social responsibility and corporate social irresponsibility: Why company size matters based on consumers’ need for self-expression. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sino-Securities Index Information Service (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Sino-Securities Index ESG Ratings Methodology (Version 2.1). Available online: https://www.chindices.com/esg-ratings.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Chen, Q. Advanced Econometrics and Stata Application, 2nd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kotyrlo, E. Simple and complex difference-in-differences approach. Appl. Econom. 2024, 73, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Chen, F. Unveiling the impact of Belt and Road Initiative on green innovation: Empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88213–88232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, A.; Møen, J. The triple difference estimator. Econom. J. 2022, 25, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Lin, D. Mandatory disclosure and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China’s “explanation for nondisclosure” requirement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J. Pretest with caution: Event-study estimates after testing for parallel trends. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2022, 4, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E.; Plümper, T. Robustness Tests for Quantitative Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Kopeinig, S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J. Econ. Surv. 2008, 22, 31–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qi, J.; Yan, G. Placebo tests for difference-in-differences: A practical guide. J. Manag. World 2025, 41, 181–203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Winsorisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | Huazheng ESG rating | 4.140 | 0.902 | 1 | 8 | No, dependent variable |

| Treat | The enterprise participated in the BRI | 0.102 | 0.303 | 0 | 1 | No, independent variables (dummy) for standard DID |

| Time | The BRI existed in the year (2013 and later) | 0.837 | 0.369 | 0 | 1 | |

| BRI | The enterprise has participated in the BRI in the year | 0.063 | 0.242 | 0 | 1 | No, independent variable (dummy) for time-varying DID |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | ln(establishment age) | 2.852 | 0.374 | 1.609 | 3.526 | Yes |

| Size | ln(total assets) | 22.178 | 1.300 | 19.847 | 26.258 | Yes |

| Employ | ln(employees) | 7.605 | 1.255 | 4.691 | 11.116 | Yes |

| Lev | Leverage ratio | 0.416 | 0.207 | 0.050 | 0.896 | Yes |

| ROA | Return on assets | 0.041 | 0.065 | −0.222 | 0.221 | Yes |

| Growth | Operating income growth ratio | 0.152 | 0.371 | −0.559 | 2.166 | Yes |

| Top1 | Shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder | 0.341 | 0.149 | 0.084 | 0.743 | Yes |

| Board | ln(board size) | 2.118 | 0.200 | 1.609 | 2.708 | Yes |

| Dual | CEO duality | 0.293 | 0.455 | 0 | 1 | No (dummy) |

| Grouping variables | ||||||

| SOE | State-owned enterprise | 0.359 | 0.480 | 0 | 1 | No (dummy) |

| MFG | Manufacturing | 0.661 | 0.474 | 0 | 1 | No (dummy) |

| Market | Main board | 0.754 | 0.431 | 0 | 1 | No (dummy) |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Unbalanced Panel Dataset | Balanced Panel Dataset | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| BRI | 0.207 *** (0.040) | 0.185 *** (0.040) | 0.195 *** (0.056) | 0.194 *** (0.056) |

| Age | −0.095 (0.090) | −0.019 (0.168) | ||

| Size | 0.192 *** (0.018) | 0.219 *** (0.033) | ||

| Employ | 0.069 *** (0.016) | 0.060 ** (0.026) | ||

| Lev | −0.817 *** (0.056) | −0.465 *** (0.109) | ||

| ROA | 0.452 *** (0.103) | 0.546 ** (0.228) | ||

| Growth | −0.087 *** (0.012) | −0.071 *** (0.022) | ||

| Top1 | 0.249 ** (0.098) | −0.002 (0.175) | ||

| Board | −0.095 * (0.050) | −0.110 (0.089) | ||

| Dual | −0.013 (0.017) | −0.039 (0.034) | ||

| Constant | 4.128 *** (0.003) | 0.067 (0.433) | 4.221 *** (0.005) | −0.758 (0.819) |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 43,484 | 43,484 | 13,005 | 13,005 |

| Adj R2 | 0.3885 | 0.4073 | 0.3971 | 0.4091 |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time-Varying DID | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFDI | Infrastructure Projects | Trade Routes | International Market | Support Services and Others | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| BRI | 0.124 (0.092) | 0.287 *** (0.065) | 0.352 *** (0.094) | 0.062 (0.077) | 0.105 (0.116) |

| Constant | 0.036 (0.456) | 0.209 (0.450) | 0.068 (0.452) | −0.083 (0.454) | 0.128 (0.457) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 39,985 | 40,152 | 39,825 | 40,257 | 39,377 |

| Adj R2 | 0.4085 | 0.4099 | 0.4095 | 0.4073 | 0.4092 |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time-Varying DID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-Owned Enterprises | Non-SOEs | Manufacturing Enterprises | Non-Manufacturing Enterprises | Enterprises on the Main Board | Enterprises on Other Boards | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| BRI | 0.231 *** (0.053) | 0.057 (0.057) | 0.056 (0.048) | 0.358 *** (0.067) | 0.199 *** (0.042) | 0.013 (0.105) |

| Constant | 0.125 (0.731) | −0.352 (0.547) | 0.197 (0.556) | 0.320 (0.757) | 0.046 (0.482) | −0.496 (1.037) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 15,732 | 27,752 | 28,636 | 14,807 | 32,995 | 10,489 |

| Adj R2 | 0.4194 | 0.4036 | 0.3978 | 0.4479 | 0.4165 | 0.3741 |

| Dependent Variable: ESG | Time-Varying DDD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SOE | MFG | Market | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| BRI | 0.249 *** (0.075) | ||

| Constant | −0.227 *** (0.073) | ||

| Control variables | 0.244 ** (0.111) | ||

| Enterprise FE | 0.028 (0.057) | 0.312 *** (0.062) | −0.033 (0.104) |

| Year FE | 0.070 (0.433) | 0.086 (0.433) | 0.048 (0.434) |

| Observations | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adj R2 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Biryukova, O. ESG Performance of Chinese Listed Enterprises Participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062776

Zhang W, Biryukova O. ESG Performance of Chinese Listed Enterprises Participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062776

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenrui, and Olga Biryukova. 2025. "ESG Performance of Chinese Listed Enterprises Participating in the Belt and Road Initiative" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062776

APA StyleZhang, W., & Biryukova, O. (2025). ESG Performance of Chinese Listed Enterprises Participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability, 17(6), 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062776