Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors

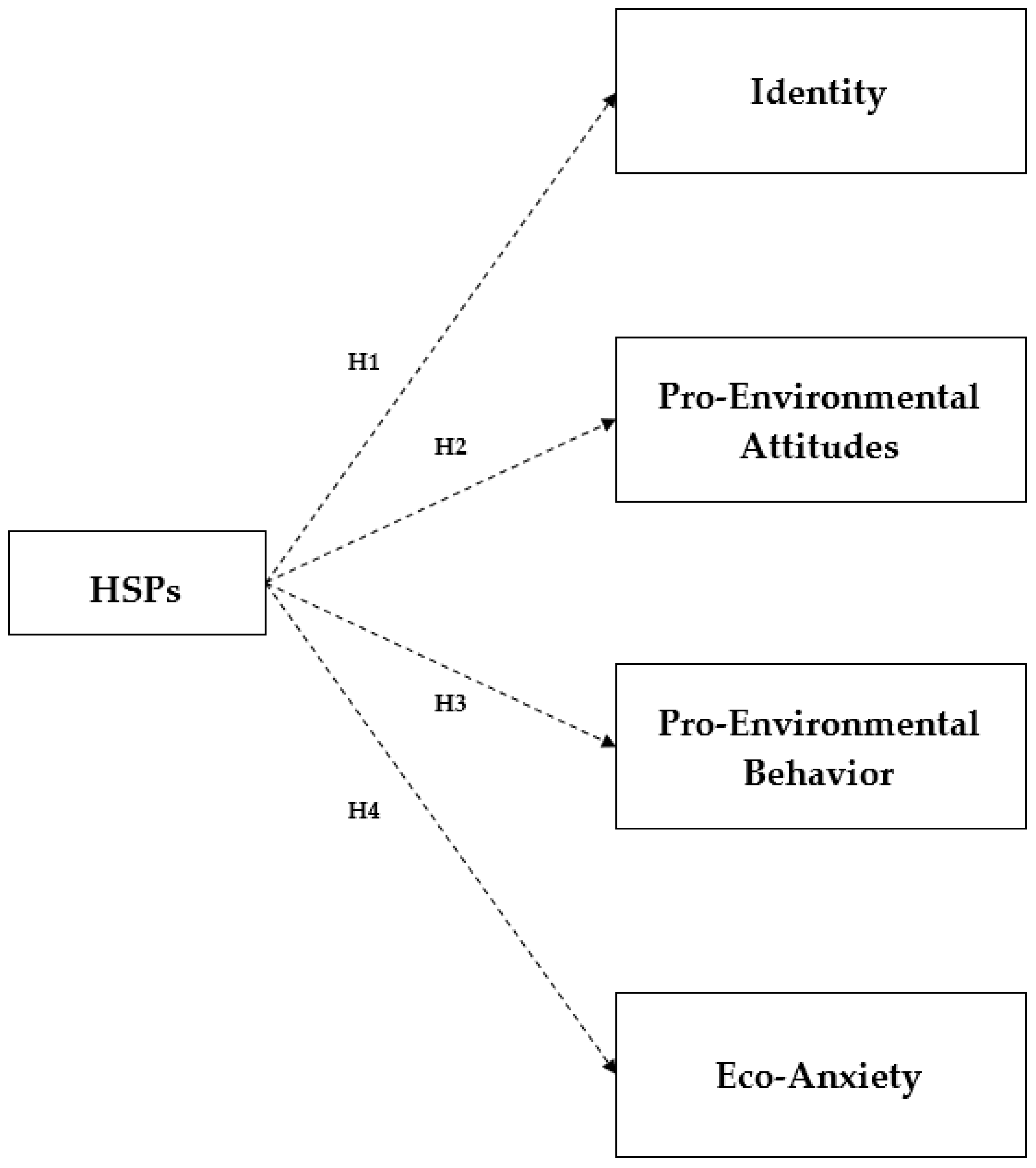

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Trait Characteristics Associated with Nature

1.2. Aim of the Study and Hypothesis Development

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Materials

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Perspectives

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scales and Authors | Number of Items | Dimensions | Reliability (Cronbach’s α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS; Aron & Aron, 1997 [3]) | 27 | Three dimensions: ease of excitation, aesthetic sensitivity, and low sensory threshold | 0.89 (Cronbach’s α: EOE = 0.81; AES = 0.72; LST = 0.78) |

| Connectedness to Nature Scale (CTN; Mayer & Frantz, 2004 [34]) | 14 | Unidimensional | 0.84 |

| Climate Change Attitude Survey (CCAS; Christensen & Knezek, 2015 [39]) | 15 | Two dimensions: beliefs and intentions | 0.78 (Cronbach’s α: beliefs = 0.90; intentions = 0.78) |

| New Ecological Paradigm (NEP; Dunlap et al., 2000 [40]) | 15 | Unidimensional | 0.83 |

| Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEB; Markle, 2013 [42]) | 19 | Four dimensions: conservation, environmental citizenship, food, and transportation | 0.76 (Cronbach’s α: conservation = 0.74; environmental citizenship = 0.65; food = 0.66; transportation = 0.62) |

| Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (EA; Hogg et al., 2021 [43]) | 13 | Four dimensions: affective symptoms, rumination, behavioral symptoms, and personal impact | 0.93 (affective symptoms = 0.92; rumination = 0.90; behavioral symptoms = 0.86; personal impact = 0.88) |

References

- Rosslenbroich, B. Properties of Life: Toward a Coherent Understanding of the Organism. Acta Biotheor. 2016, 64, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluess, M. Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2015, 9, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Sensory-Processing Sensitivity and Its Relation to Introversion and Emotionality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, J. Variation in Susceptibility to Environmental Influence: An Evolutionary Argument. Psychol. Inq. 1997, 8, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J.; Boyce, W.T. Biological Sensitivity to Context. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A.; Jagiellowicz, J. Sensory Processing Sensitivity: A Review in the Light of the Evolution of Biological Responsivity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Moscardino, U.; Nocentini, A.; Pluess, K.; Pluess, M. Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Its Association with Personality Traits and Affect: A Meta-Analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2019, 81, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. The Neuropsychology of Temperament. In Explorations in Temperament: International Perspectives on Theory and Measurement; Strelau, J., Angleitner, A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 105–128. ISBN 978-1-4899-0643-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; White, T.L. Behavioral Inhibition, Behavioral Activation, and Affective Responses to Impending Reward and Punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, H.J. Personality: Biological Foundations. In The Neuropsychology of Individual Differences; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 151–207. ISBN 978-0-12-718670-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, J. Galen’s Prophecy: Temperament in Human Nature; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-429-50028-2. [Google Scholar]

- Greven, C.U.; Lionetti, F.; Booth, C.; Aron, E.N.; Fox, E.; Schendan, H.E.; Pluess, M.; Bruining, H.; Acevedo, B.; Bijttebier, P.; et al. Sensory Processing Sensitivity in the Context of Environmental Sensitivity: A Critical Review and Development of Research Agenda. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 98, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, M.; Timmel, L.; Baxley, K.; Killingsworth, P. Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Its Relation to Parental Bonding, Anxiety, and Depression. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 1429–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A.; Davies, K.M. Adult Shyness: The Interaction of Temperamental Sensitivity and an Adverse Childhood Environment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluess, M.; Boniwell, I. Sensory-Processing Sensitivity Predicts Treatment Response to a School-Based Depression Prevention Program: Evidence of Vantage Sensitivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 82, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagt, M.; Dubas, J.S.; van Aken, M.A.G.; Ellis, B.J.; Deković, M. Sensory Processing Sensitivity as a Marker of Differential Susceptibility to Parenting. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E.; Pluess, M. The Personality Trait of Environmental Sensitivity Predicts Children’s Positive Response to School-Based Antibullying Intervention. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolewska, K.A.; McCabe, S.B.; Woody, E.Z. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Highly Sensitive Person Scale: The Components of Sensory-Processing Sensitivity and Their Relation to the BIS/BAS and “Big Five”. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; Falegnami, A.; Meleo, L.; Romano, E. The GreenSCENT Competence Frameworks. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-349259-7. [Google Scholar]

- Setti, A.; Lionetti, F.; Kagari, R.L.; Motherway, L.; Pluess, M. The Temperament Trait of Environmental Sensitivity Is Associated with Connectedness to Nature and Affinity to Animals. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How Might Contact with Nature Promote Human Health? Promising Mechanisms and a Possible Central Pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-0-521-34939-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti, F.; Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Burns, G.L.; Jagiellowicz, J.; Pluess, M. Dandelions, Tulips and Orchids: Evidence for the Existence of Low-Sensitive, Medium-Sensitive and High-Sensitive Individuals. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, M.; Belsky, J. Vantage Sensitivity: Individual Differences in Response to Positive Experiences. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, E.; Lionetti, F.; Murphy, M.; Setti, A. Watching a Video of Nature Reduces Negative Affect and Rumination, While Positive Affect Is Determined by the Level of Sensory Processing Sensitivity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional Affinity Toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, H.; Lionetti, F.; Pluess, M.; Setti, A. Individual Traits Are Associated with Pro-Environmental Behaviour: Environmental Sensitivity, Nature Connectedness and Consideration for Future Consequences. People Nat. 2024, 6, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeff, T. The Highly Sensitive Person’s Survival Guide: Essential Skills for Living Well in an Overstimulating World; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-60882-848-7. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, J.M.; Dale, G.; Baird, J. People with Sensory Processing Sensitivity Connect Strongly to Nature Across Five Dimensions. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2024, 20, 2341493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kurisu, K. Behavior Model Development for Understanding PEBs. In Pro-Environmental Behaviors; Kurisu, K., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 47–62. ISBN 978-4-431-55834-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; Loreau, M.; de Mazancourt, C.; Singer, M.C.; Parmesan, C. Psychological and Physical Connections with Nature Improve Both Human Well-Being and Nature Conservation: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 277, 109842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. New Environmental Theories: Empathizing with Nature: The Effects ofPerspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 981814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological Grief as a Mental Health Response to Climate Change-Related Loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Weiss, D.J. The Impact of Anonymity on Responses to Sensitive Questions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.; Knezek, G. The Climate Change Attitude Survey: Measuring Middle School Student Beliefs and Intentions to Enact Positive Environmental Change. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 773–788. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonin, S.; Benedetto, D. Exploring Sustainability Concerns and Ecosystem Services: The Role of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale in Understanding Public Opinion. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle, G.L. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Does It Matter How It’s Measured? Development and Validation of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS). Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect Size Guidelines for Individual Differences Researchers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, B.P.; Aron, E.N.; Aron, A.; Sangster, M.-D.; Collins, N.; Brown, L.L. The Highly Sensitive Brain: An fMRI Study of Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Response to Others’ Emotions. Brain Behav. 2014, 4, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why Is Nature Beneficial?: The Role of Connectedness to Nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-674-26839-5. [Google Scholar]

- Diessner, R.; Niemiec, R.M. Can Beauty Save the World? Appreciation of Beauty Predicts Proenvironmental Behavior and Moral Elevation Better Than 23 Other Character Strengths. Ecopsychology 2023, 15, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J. “Bats, Snakes and Spiders, Oh My!” How Aesthetic and Negativistic Attitudes, and Other Concepts Predict Support for Species Protection. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, M.; Duradoni, M.; Barbagallo, G.; Guazzini, A. Implicit Association Test (IAT) Toward Climate Change: A PRISMA Systematic Review. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Valdrighi, G.; Donati, A.; Fiorenza, M.; Puddu, L.; Guazzini, A. Development and Validation of the Readiness to Change Scale (RtC) for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Szczypiński, J.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J.M.; Klöckner, C.A.; Marchewka, A. Beyond Climate Anxiety: Development and Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE): A Measure of Multiple Emotions Experienced in Relation to Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 83, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean (S.D.) | Skew. | Kurt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTN | 34 | 67 | 50.88 (6.28) | −0.123 | −0.401 |

| CCAS—Belief | 14 | 45 | 40.82 (4.88) | −2.18 | 6.06 |

| CCAS—Intention | 10 | 30 | 25.09 (4.01) | −0.984 | 0.859 |

| NEP | 31 | 75 | 57.67 (7.5) | −0.364 | −0.197 |

| HSPS—Ease of Excitation | 14 | 59 | 40.31 (8.067) | −0.211 | −0.302 |

| HSPS—Aesthetic Sensitivity | 14 | 35 | 25.40 (4.21) | −0.280 | −0.282 |

| HSPS—Low Sensory Threshold | 6 | 29 | 16.53 (5.03) | 0.047 | −0.668 |

| HSPS—Total Score | 47 | 132 | 88.37 (15.93) | −0.045 | −0.432 |

| PEBS—Conservation | 16 | 35 | 27.91 (3.60) | −0.57 | 0.33 |

| PEBS—Environmental Citizenship | 6 | 26 | 13.42 (3.90) | 0.446 | 0.212 |

| PEBS—Food | 3 | 15 | 10.19 (4.90) | −0.434 | −1.422 |

| EA—Affective Symptoms | 0 | 12 | 4.45 (2.75) | 0.323 | −0.172 |

| EA—Rumination | 0 | 9 | 2.79 (1.89) | −0.264 | −0.277 |

| EA—Behavioral Symptoms | 0 | 9 | 2.54 (2.24) | 0.653 | −240 |

| EA—Personal Impact | 0 | 0 | 3.00 (2.11) | 0.420 | −0.171 |

| Variable | CTN | NEP | CCAS—Belief | CCAS—Intention | PEBS—Conservation | PEBS—Environmental Citizenship | PEBS—Food | PEBS—Transportation | EA—Affective Symptoms | EA—Rumination | EA—Behavioral Symptoms | EA—Personal Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPS—Ease of Excitation | 0.175 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.110 ** | 0.046 | 0.212 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.326 ** |

| HSPS—Aesthetic Sensitivity | 0.472 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.303 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.396 ** |

| HSPS—Low Sensory Threshold | 0.240 ** | 0.104 * | 0.093 * | 0.040 | 0.141 ** | 0.110 * | 0.259 ** | 0.136 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.344 ** | 0.295 ** |

| HSPS Total score | 0.319 ** | 0.240 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.407 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duradoni, M.; Fiorenza, M.; Bellotti, M.; Severino, F.P.; Valdrighi, G.; Guazzini, A. Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062740

Duradoni M, Fiorenza M, Bellotti M, Severino FP, Valdrighi G, Guazzini A. Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062740

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuradoni, Mirko, Maria Fiorenza, Martina Bellotti, Franca Paola Severino, Giulia Valdrighi, and Andrea Guazzini. 2025. "Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062740

APA StyleDuradoni, M., Fiorenza, M., Bellotti, M., Severino, F. P., Valdrighi, G., & Guazzini, A. (2025). Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability, 17(6), 2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062740