Possible Effects of Licensed Warehousing System on Hazelnut Producers’ Incomes in Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Calculation of Financial Results in Licensed Warehousing

2.2. Legislation Regarding Licensed Warehousing Supports

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics. Hazelnut Production Statistics of Countries in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 15 December 2024).

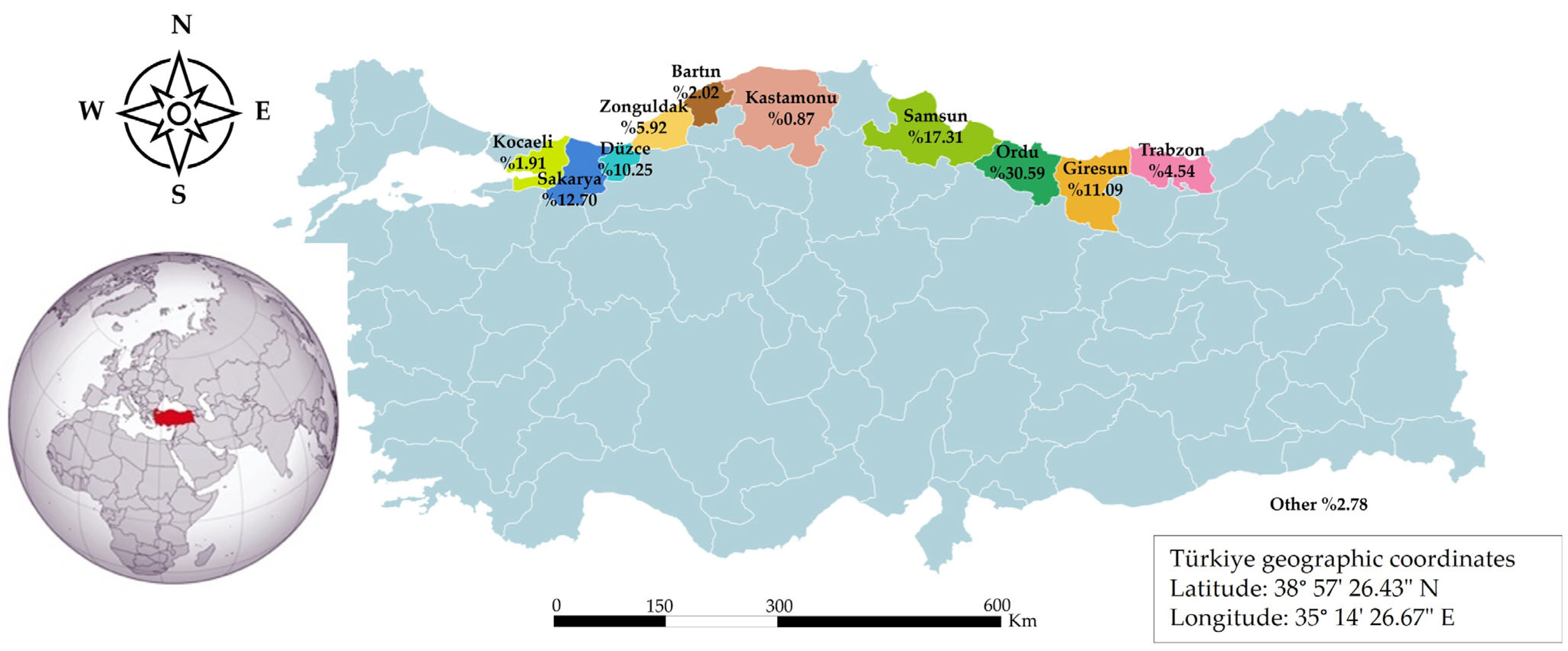

- TurkStat. Hazelnut Production Statistics of Provinces in Türkiye for 2023. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2024. Available online: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?locale=tr (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- OG. Law No. 5300 on Licensed Warehousing of Agricultural Products. Official Gazette No 25730 dated 10/2/2005. 2005. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2005/02/20050217-1.htm (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Karabak, S.; Gürler, A.Z. The mechanism of licensed warehousing system and its applicability in Türkiye. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 5, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Vonck, I.; Notteboom, T. Economic Analysis of the Warehousing and Distribution Market in Northwest Europe; UAntwerp Publishers: Wavre/Brussels, Belgium, 2012; pp. 28–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, M. Warehousing System in Agricultural: Grain Market Case; Publication number: 2971; Ministry of Development Publishers: Ankara, Türkiye, 2017; pp. 128–171. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut, K. Rent support payments in licensed warehousing service. Financ. Anal. 2019, 29, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ketboğa, M. The developments of transition to licensed warehousing system on the dried apricot sector. Bartın Uni. J. F. Econ. And Admin. Sci. 2020, 11, 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Ram, C.L.; Jha, S.N.; Vishwakarma, R.K. Warehouse storage management of wheat and their role in food security. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, H.G.; Bulut, A. A Research on licensed warehousing activities in Türkiye (Case of LİDAŞ in Mucur district of Kırşehir province). Turk. JAF Sci. Technol. 2021, 9, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M.M.; Kumar, K.N.R. Performance of agri-warehousing in India. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. and Soc. 2023, 41, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, M.; Telli, Ü.Y. Licensed warehousing for cereal production and export: Central anatolian example. J. Int. Tra. and Econ. Res. 2024, 8, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabaş, S. Constraints on the integration and adoption of licensed warehousing system in Türkiye’s agricultural markets. Turk. JAF Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayani, S.; Darwanto, D.H.; Irham, J. Factors influencing farmers to join warehouse receipt system in Barito Kuala Regency, South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Eurasia J. Biosci. 2019, 13, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, E.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Datta, A.; Nguyen, L.T. Farmers’ perceptions of the warehouse receipt system in Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengiz, Z.M.; Ayyıldız, M. The perspective of grain producers on licensed warehousing: The example of yerkoy district of Yozgat province. J. Tekirdag Agric. Fac. 2023, 20, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, R.F.B. Understanding the factors influencing the participation of the warehouse receipt system program for pepper farmers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Innovation and Trends in Economy, Tangerang, Indonesia, 5 November 2020; pp. 802–813. [Google Scholar]

- Savran, M.K.; Demirbaş, N. The warehouse receipt system in terms of olive oil producers in Turkey. J. Agric. F. Ege Uni. 2017, 54, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, J.; Onumah, G. The role of warehouse receipt systems in enhanced commodity marketing a rural livelihoods in Africa. Food Policy 2002, 27, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, J.G.; Kaserwa, N. Improving smallholder farmers access to finance through warehouse receipt system in Tanzania. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Res. 2015, 1, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, M.J.; Mulangu, F.M.; Kemeze, F.H. Warehouse receipt financing for smallholders in developing countries: Challenges and limitations. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, N.; Tahsin, E. Role of electronic warehouse receipt system in development of commodity exchanges: An assessment for Türkiye. J. Agric. Econ. Res. 2019, 5, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Onumah, G.E. Warehouse receipts and securitisation in agricultural finance to promote lending to smallholder farmers in Africa: Potential benefits and legal/regulatory issues. Unif. Law Rev. 2013, 17, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Lotfi, M. The optimal warehouse capacity: A queuing-based fuzzy programming approach. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ceyhan, V.; Gunhan, U. Benchmarking of alternative business models in licensed grain warehouses and capacity optimization. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 25, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakić, V.; Kovačević, V.; Ivkov, I.; Mirović, V. Importance of public Warehouse system for financing agribusiness sector. Econ. Agric. 2014, 61, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan, V.; Karabak, S.; Taşcı, R.; Bolat, M.; Hazneci, K.; Kavakoğlu, H.; Okur, Y.; Kaya, E.; Pehlivan, A.; Acar, O. Structural and Economic Analysis of Licensed Warehousing System in Wheat and Barley Trade and Capacity Optimization in Warehouses; TAGEM Publications: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018; pp. 30–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hazneci, K.; Hazneci, E. Measuring the producer level economic benefit of licensed warehousing of hazelnut in Turkey. In Proceedings of the Imcofe V. International Multidisciplinary Congress of Eurasia, Barcelona, Spain, 24–26 July 2018; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Hazneci, E.; Çelikkan, G.; Naycı, E. Marketing structure of hazelnut producing enterprises in Giresun province. In Agricultural Products Production and Agricultural Marketing; Iksad Publishing House: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021; pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Trade (Türkiye). Licensed Warehousing Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://ticaret.gov.tr/ic-ticaret/lisansli-depoculuk/istatistiklerle-lisansli-depoculuk (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Ministry of Trade (Türkiye). Licensed Warehousing Establishment and Activity Permits. 2024. Available online: https://ticaret.gov.tr/ic-ticaret/lisansli-depoculuk/kurulus-ve-faaliyet-izinleri (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Central Bank (Türkiye). Weighted Average Interest Rates Applied to Loans Granted by Banks. 2024. Available online: https://evds2.tcmb.gov.tr/index.php?/evds/portlet/0QRrRj0ew0Y%3D/tr (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- OG. Decision No. 2017/11093 Licensed Warehousing Rent Support Law. Official Gazette No 30307 Dated 20/01/2018. 2018. Available online: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/01/20180120-6.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- OG. Decision Number 2018/11188 Providing Low-Interest Investment and Business Loans for Agricultural Production. Official Gazette No 30307 Dated 20/01/2018. 2018. Available online: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/01/20180120-4.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- OG. Notification Number 2023/49 on Support Payment for Agricultural Products Stored in Licensed Warehouses. Official Gazette No 32421 dated 06/01/2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2024/01/20240106-6.htm (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- TurkStat. Monthly Hazelnut Prices in Türkiye According to Years. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2024. Available online: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=110&locale=tr (accessed on 7 December 2024).

| 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August | 2555.39 | 2650.46 | 2900.98 | 2514.22 | 2716.52 | 4341.44 | 5267.86 |

| September | 2720.12 | 2592.49 | 3246.54 | 2350.15 | 2741.49 | 4978.27 | 4196.20 |

| October | 2769.92 | 2693.06 | 3656.11 | 2340.95 | 2818.65 | 5712.24 | 4205.39 |

| November | 2695.91 | 2672.21 | 3747.68 | 2380.35 | 2858.91 | 6097.85 | 4541.52 |

| December | 2647.53 | 2683.15 | 3808.81 | 2579.97 | 2784.47 | 5971.15 | 4538.54 |

| January | 2857.49 | 2793.12 | 3850.05 | 2602.25 | 2832.87 | 5995.68 | 3787.89 |

| February | 2856.08 | 2975.68 | 3957.53 | 2587.68 | 2856.16 | 6203.10 | 3604.63 |

| March | 3016.40 | 3054.61 | 3698.09 | 2523.25 | 2754.99 | 6296.83 | 3423.55 |

| April | 3024.45 | 3160.42 | 3522.79 | 2538.31 | 3144.58 | 6230.78 | 3330.11 |

| May | 2964.55 | 3036.78 | 3433.59 | 2523.62 | 4036.72 | 6534.05 | 3136.75 |

| June | 2935.77 | 3061.45 | 3138.64 | 2554.75 | 4338.94 | 6782.27 | 3126.51 |

| July | 2922.58 | 2975.62 | 2869.99 | 2615.93 | 4262.10 | 6171.59 | 3022.77 |

| 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | |

| August | 3435.87 | 2559.45 | 1837.63 | 2928.11 | 2877.75 | 2632.23 | 2752.99 |

| September | 4347.83 | 2543.22 | 1793.66 | 2762.22 | 2847.71 | 2763.20 | 2814.32 |

| October | 4005.94 | 2460.23 | 2077.01 | 2755.62 | 2849.93 | 2599.58 | 2771.40 |

| November | 3528.75 | 2320.16 | 2389.51 | 2859.77 | 2920.04 | 2230.30 | 2749.73 |

| December | 3149.97 | 2326.06 | 2512.19 | 2918.99 | 2758.69 | 1796.21 | 3161.99 |

| January | 2902.36 | 2346.03 | 2514.25 | 3002.62 | 2899.66 | 2107.36 | 3312.80 |

| February | 3066.15 | 2403.38 | 2810.69 | 3216.16 | 3069.69 | 2356.63 | 3321.94 |

| March | 2940.58 | 2409.25 | 2890.51 | 3142.01 | 2735.89 | 2301.31 | 2907.33 |

| April | 2808.01 | 2385.28 | 2813.92 | 3022.46 | 2610.66 | 2267.84 | 3226.57 |

| May | 2758.24 | 2170.30 | 2717.60 | 3230.75 | 2492.13 | 2217.75 | 3092.35 |

| June | 2725.21 | 2093.68 | 2871.68 | 3350.06 | 2426.52 | 2100.83 | 2760.52 |

| July | 2643.36 | 2032.43 | 3025.29 | 3104.61 | 2447.48 | 2143.50 | 2646.21 |

| 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September | 136.98 | −117.31 | 388.71 | −182.81 | 80.62 | 702.4 | −873.69 | 875.14 |

| October | 137.78 | −149.84 | 865.63 | −197.1 | 112.29 | 1550.87 | −929.31 | 670.02 |

| November | 90.8 | −165.21 | 881.9 | −175.74 | 191.42 | 1817.29 | −716.84 | 388.05 |

| December | 67.02 | −5.86 | 1061.21 | 6.13 | 155.23 | 1839.54 | −672.66 | 188.87 |

| January | 203.09 | 168.93 | 1020.21 | −2.23 | 410.07 | 1910.70 | −1306.08 | 124.16 |

| February | 272.73 | 391.74 | 940.17 | −17.3 | 389.7 | 2405.48 | −1539.14 | 219.03 |

| March | 461.38 | 437.05 | 777.86 | −38.58 | 286.52 | 2687.33 | −1821.20 | 82.66 |

| April | 372.48 | 415.52 | 581.9 | −48.01 | 537.63 | 2625.46 | −2020.71 | −68.35 |

| May | 392.45 | 376.73 | 504.05 | −52 | 1348.37 | 2803.07 | −2183.51 | −215.73 |

| June | 396.68 | 419.17 | 218.63 | 54.94 | 1687.87 | 3135.49 | −2166.29 | −320.01 |

| July | 288.7 | 395.1 | −89.21 | 139.42 | 1558.88 | 2394.42 | −2266.39 | −411.55 |

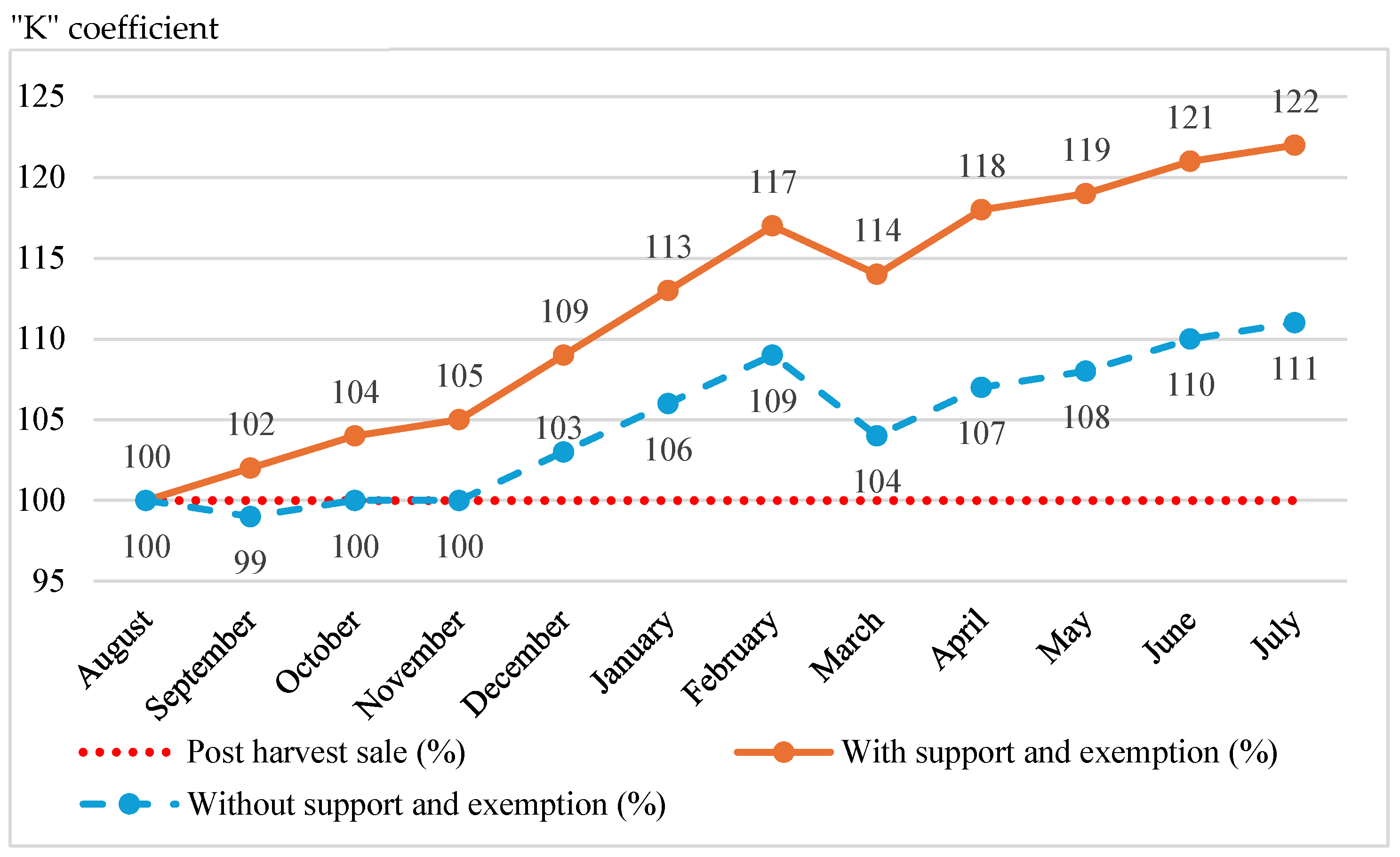

| 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | K | R | |

| September | −78.26 | 132.76 | −152.84 | 41.61 | 277.87 | 1660.10 | 1.02 | 2.26 |

| October | −37.07 | 231.16 | −131.34 | 171.96 | 292.55 | 1619.29 | 1.04 | 4.24 |

| November | −50.69 | 358.77 | −60.4 | 273.48 | 230.48 | 1564.13 | 1.05 | 5.12 |

| December | −72.98 | 474.99 | 43.91 | 2.99 | 270.39 | 1968.48 | 1.09 | 9.15 |

| January | −111.85 | 506.06 | 160.23 | 14.21 | 513.04 | 2123.26 | 1.13 | 12.91 |

| February | −65.53 | 733.3 | 432.27 | 44.37 | 773.13 | 2118.74 | 1.17 | 17.23 |

| March | −6.46 | 919.35 | 481.51 | −79.43 | 864.12 | 1709.05 | 1.14 | 13.91 |

| April | 63.34 | 957 | 575.22 | −25.08 | 786.22 | 2060.70 | 1.18 | 17.96 |

| May | −6.31 | 938.9 | 779.88 | −103.49 | 852 | 1923.27 | 1.19 | 18.63 |

| June | −24.66 | 913.39 | 794.2 | −108.96 | 847.27 | 2002.35 | 1.21 | 20.81 |

| July | −73.61 | 1012.45 | 564.8 | −95.79 | 860.45 | 1956.00 | 1.22 | 22.09 |

| 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September | 86.76 | −164.37 | 338.17 | −222.91 | 34.87 | 630.90 | −940.68 | 809.86 |

| October | 62.46 | −220.42 | 789.30 | −256.99 | 44.73 | 1435.88 | −1021.61 | 570.11 |

| November | −10.85 | −263.87 | 781.76 | −255.34 | 99.01 | 1660.14 | −842.12 | 259.20 |

| December | −58.27 | −130.46 | 933.47 | −94.79 | 40.74 | 1635.06 | −831.91 | 38.40 |

| January | 54.40 | 23.68 | 871.02 | −125.04 | 271.54 | 1664.39 | −1490.15 | −44.12 |

| February | 96.07 | 222.67 | 765.06 | −164.91 | 237.65 | 2114.95 | −1743.03 | 35.74 |

| March | 264.67 | 244.54 | 570.12 | −210.87 | 111.14 | 2363.11 | −2054.71 | −129.55 |

| April | 154.64 | 194.62 | 354.51 | −242.23 | 337.60 | 2269.61 | −2283.84 | −306.32 |

| May | 156.99 | 135.75 | 266.95 | −257.07 | 1131.65 | 2449.30 | −2458.07 | −459.25 |

| June | 157.09 | 174.53 | −25.90 | −156.72 | 1459.04 | 2774.87 | −2438.17 | −574.56 |

| July | 43.44 | 144.13 | −340.74 | −73.41 | 1324.51 | 2034.71 | −2545.13 | −674.30 |

| 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | K | R | |

| September | −139.98 | 82.15 | −225.95 | −31.04 | 185.05 | 1547.75 | 0.99 | −0.53 |

| October | −141.30 | 165.13 | −232.28 | 71.70 | 161.52 | 1463.57 | 1.00 | 0.21 |

| November | −188.27 | 266.53 | −185.75 | 151.95 | 77.61 | 1372.65 | 1.00 | −0.04 |

| December | −238.55 | 352.91 | −107.53 | −138.34 | 111.99 | 1736.90 | 1.03 | 2.86 |

| January | −313.97 | 362.66 | −11.16 | −152.54 | 369.29 | 1854.79 | 1.06 | 5.54 |

| February | −306.85 | 571.91 | 240.67 | −149.63 | 608.02 | 1817.44 | 1.09 | 8.81 |

| March | −282.61 | 733.69 | 271.62 | −302.16 | 678.45 | 1378.61 | 1.04 | 4.48 |

| April | −241.57 | 757.28 | 352.84 | −249.86 | 592.92 | 1700.08 | 1.07 | 7.48 |

| May | −302.49 | 746.38 | 571.41 | −315.89 | 655.31 | 1559.52 | 1.08 | 7.90 |

| June | −300.61 | 727.97 | 587.21 | −318.68 | 658.12 | 1637.19 | 1.10 | 9.84 |

| July | −340.56 | 816.46 | 350.90 | −301.32 | 682.22 | 1636.62 | 1.11 | 10.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hazneci, E. Possible Effects of Licensed Warehousing System on Hazelnut Producers’ Incomes in Türkiye. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062737

Hazneci E. Possible Effects of Licensed Warehousing System on Hazelnut Producers’ Incomes in Türkiye. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062737

Chicago/Turabian StyleHazneci, Esin. 2025. "Possible Effects of Licensed Warehousing System on Hazelnut Producers’ Incomes in Türkiye" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062737

APA StyleHazneci, E. (2025). Possible Effects of Licensed Warehousing System on Hazelnut Producers’ Incomes in Türkiye. Sustainability, 17(6), 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062737