The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Environmental Attitude and Purchase Intention

2.3. Subjective Norms and Purchase Intention

2.4. Perceived Behavioral Control and Purchase Intention

2.5. Social Media and Its Influence on Purchase Intention, Environmental Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioral Control

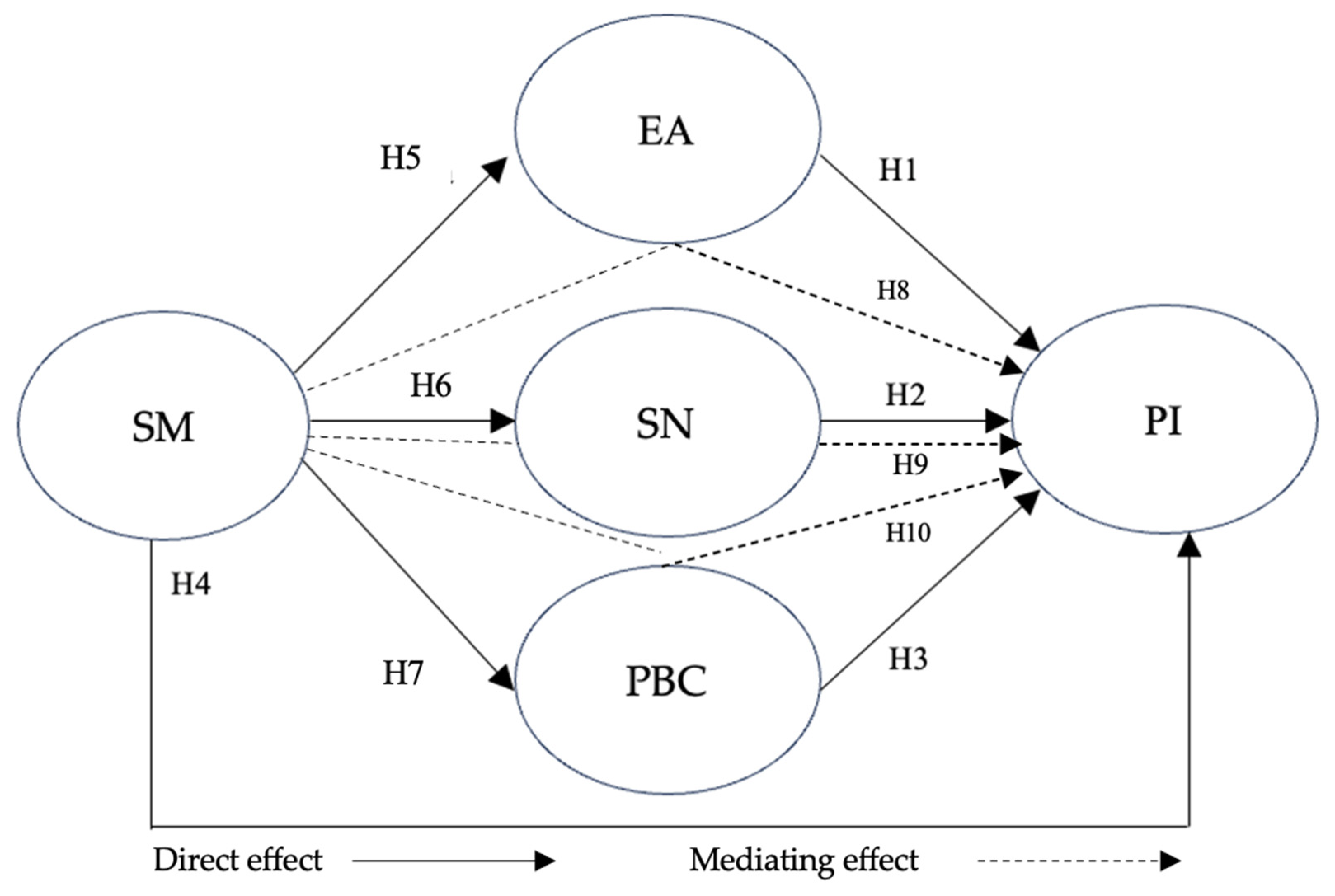

2.6. Research Model

3. Method

3.1. Instrument Design and Data Collection

3.2. Internal Consistency of the Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Measurement Model Estimation

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of EA, SN, and PBC on the PI of Organic Products

5.2. Impact of SM on PI of Organic Products

5.3. Impact of SM on EA, SN, and PBC

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical, Practical, and Social Implications

6.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Author |

|---|---|

| EA1. Environmental protection is important to me when making product purchases. | Adapted from: Carrión et al. [7] |

| EA2. I believe that green products help to reduce pollution (water, air, etc.) | |

| EA3. I believe that green products help to save nature and its resources. | |

| EA4. Given a choice, I will prefer a green product over a conventional product. | |

| SN1. People who are important to me thinks that I should buy organic products. | |

| SN2. My interaction with people influences me to buy organic products. | |

| SN3. My acquaintances would approve of my decision to buy organic products. | |

| SN4. Most of my friends think that buying organic products is the right thing to do. | |

| PBC1. It is entirely my decision to buy organic products. | |

| PBC2. I cannot pay more to buy organic products. | |

| PBC3. I require a lot of time to search for organic products. | |

| PBC4. I know exactly where to buy organic products. | |

| PI1. I intend to buy organic products. | |

| PI2. I plan to purchase organic products. | |

| PI3 I will purchase organic products in my next purchase. | |

| PI4. Next month I will buy organic products. | |

| SM1. I usually read information and articles about sustainable issues on social media. | Li et al. [4] |

| SM2. I usually watch sustainable-related pictures and videos on social media. | |

| SM3. I usually read sustainable-related articles and pamphlets of corporations on social media and know their sustainable policy and strategy. | |

| SM4. I initially followed the social media accounts of some green lifestyle organizations |

References

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, N.K. Impact of social media on consumer purchase intention: A developing country perspective. In Handbook of Research on the Role of Human Factors in IT Project Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 260–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, K.; Chiru, C.; Ciuchete, S.G. Exploring the eco-attitudes and buying behaviour of Facebook users. Amfiteatru Econ. 2012, 14, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.-L.; Chao, C.-M.; Lin, C.-H. The Role of Social Media Marketing in Green Product Repurchase Intention. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Ho, K.K.W.; So, S. The Use of Social Media in Sustainable Green Lifestyle Adoption: Social Media Influencers and Value Co-Creation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafyana, S.; Alzubi, A. Social Media’s Influence on Eco-Friendly Choices in Fitness Services: A Mediation Moderation Approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Madni, G.R. Impact of Social Media on Young Generation’s Green Consumption Behavior through Subjective Norms and Perceived Green Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Factors influencing green purchasing inconsistency of Ecuadorian millennials. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2461–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G.; Martínez Quiroz, A.K. The influence of price and availability on university millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino Rivera, H.J.; Barcellos-Paula, L. Personal Variables in Attitude toward Green Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Foods 2024, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Yen, N.T.; Hoang, D.P. The formation of attitudes and intention towards green purchase: An analysis of internal and external mechanisms. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2192844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Lobo, A.; Vu, P.A. Organic food purchases in an emerging market: The influence of consumers’ personal factors and green marketing practices of food stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital 2022 Global Overview Report. Estadísticas de la Situación Digital de Ecuador. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-overview-report (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Mentino: Estado Digital Ecuador Octubre de 2024. Available online: https://www.mentinno.com/estado-digital-ecuador-octubre-2024-2/#descarga (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Armutcu, B.; Ramadani, V.; Zeqiri, J.; Dana, L.P. The role of social media in consumers’ intentions to buy green food: Evidence from Türkiye. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1923–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Uniyal, D.P.; Sangroya, D. Investigating consumers’ green purchase intention: Examining the role of economic value, emotional value and perceived marketplace influence. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F.A.; Sosianika, A.; Suhartanto, D. Indonesian millennials’ halal food purchasing: Merely a habit? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Naranjo Armijo, F.; Veas-González, I.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Guerra-Regalado, W.F. Influential factors in the consumption of organic products: The case of Ecuadorian and Peruvian millennials. Multidiscip. Bus. Rev. 2024, 17, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Bernatonienė, J. Why determinants of green purchase cannot be treated equally? The case of green cosmetics: Literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Ortiz-Regalado, O. The influence of skepticism on the university Millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3800–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Sivapalan, A.; Das, M.; Maseeh, H.I.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Strong, C.; Sangroya, D. A meta-analytic integration of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm model to predict green consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 1141–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; La Barbera, F.; Schmidt, S.; Rollero, C.; Fedi, A. Differentiating emotions in the theory of planned behaviour: Evidence of improved prediction in relation to sustainable food consumerism. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.I.; Ioanid, A. Factors influencing consumer behavior toward green products: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research trends in green product for environment: A bibliometric perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Veas-González, I.; Naranjo-Armijo, F.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerra-Regalado, W.; Vidal-Silva, C. Advertising and Eco-Labels as Influencers of Eco-Consumer Attitudes and Awareness—Case Study of Ecuador. Foods 2024, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Toro, O.N.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Valencia, J.; Londoño, W.; Gallegos, A. Green purchase intention factors: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustain. Env. 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Assessing consumer behavior in sustainable product markets: A structural equation modeling approach with partial least squares analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K. How environmental concerns influence consumers’ anticipated emotions towards sustainable consumption: The moderating role of regulatory focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, H.; Aydin, C. Investigating consumers’ food waste behaviors: An extended theory of planned behavior of Turkey sample. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Chen, H.S. To buy or not to buy? Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions for suboptimal food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setyarko, Y.; Noermijati, N.; Rahayu, M.; Sudjatno, S. The role of consumer green assurance in strengthening the influence of purchase intentions on organic vegetable purchasing behavior: Theory of planned behavior approach. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2024, 21, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varah, F.; Mahongnao, M.; Pani, B.; Khamrang, S. Exploring young consumers’ intention toward green products: Applying an extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 9181–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliniasari, A.R.; Mas’od, A. Understanding factors shaping green cosmetic purchase intentions: Insights from attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.M.; Ha, N.T.; Ngo TV, N.; Pham, H.T.; Duong, C.D. Environmental corporate social responsibility initiatives and green purchase intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutcu, B.; Zuferi, R.; Tan, A. Green product consumption behaviour, green economic growth and sustainable development: Unveiling the main determinants. J. Enterp. Communities People Places GloB. Econ. 2024, 18, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Shan, M.; Cao, R.; Chen, H. Informers” or “entertainers”: The effect of social media influencers on consumers’ green consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiswarya, U.B.; Harindranath, R.M.; Challapalli, P. Social Media Information Sharing: Is It a Catalyst for Green. Consumption among Gen. X and Gen. Y Cohorts? Sustainability 2024, 16, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgammal, I.; Ghanem, M.; Al-Modaf, O. Sustainable Purchasing Behaviors in Generation Z: The Role of Social Identity and Behavioral Intentions in the Saudi Context. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Zhu, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, Q. Understanding the Influences on Green Purchase Intention with Moderation by Sustainability Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semprebon, E.; Mantovani, D.; Demczuk, R.; Souto Maior, C.; Vilasanti, V. Green consumption: A network analysis in marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H. Exploring social media determinants in fostering pro-environmental behavior: Insights from social impact theory and the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1445549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pan, J. The investigation of green purchasing behavior in China: A conceptual model based on the theory of planned behavior and self-determination theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, R. On assuring valid measures for theoretical models using survey data. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 57, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chion, S.; Charles, V. Analıtica de Datos para la Modelacion Estructural, 1st ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming consumers’ intention to purchase green products: Role of social media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Ogiemwonyi, O.; Alshareef, R.; Alsolamy, M.; Mat, N.; Azizan, N.A. Do social media influence altruistic and egoistic motivation and green purchase intention towards green products? An experimental investigation. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Castillo, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, R. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Syed, A. Impact of online social media activities on marketing of green products. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.-A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Alt, M.-A. Social Media Goes Green—The Impact of Social Media on Green Cosmetics Purchase Motivation and Intention. Information 2020, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Understanding consumers’ intentions to purchase green products in the social media marketing context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics. | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | Guayaquil | 430 | 100% |

| Education Level | Undergraduate | 275 | 64% |

| Master’s degree | 155 | 36% | |

| Age | Under 23 years old | 35 | 8% |

| Between 23 and 28 years old | 150 | 35% | |

| Between 29 and 34 years old | 130 | 30% | |

| Between 35 and 44 years old | 59 | 14% | |

| Between 45 and 55 years old | 41 | 10% | |

| Over 55 years old | 15 | 3% | |

| Gender | Female | 247 | 57% |

| Male | 183 | 43% |

| Variable | Item | Loading Factor | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | EA1 | 0.955 | 0.943 | 0.948 | 0.860 |

| EA 2 | 0.916 | ||||

| EA 3 | 0.911 | ||||

| SN | SN 2 | 0.945 | 0.932 | 0.938 | 0.835 |

| SN 3 | 0.871 | ||||

| SN 4 | 0.924 | ||||

| PBC | PBC2 | 0.906 | 0.881 | 0.938 | 0.835 |

| PBC 3 | 0.783 | ||||

| PBC 4 | 0.884 | ||||

| SM | RS1 | 0.866 | 0.825 | 0.864 | 0.680 |

| RS3 | 0.862 | ||||

| RS4 | 0.739 | ||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.696 | 0.857 | 0.889 | 0.670 |

| PI2 | 0.911 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.730 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.913 | ||||

| Total CA | 0.824 | ||||

| EA | SN | PBC | SM | PI | SR AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | 0.860 | 0.927 | ||||

| SN | 0.135 ** | 0.835 | 0.913 | |||

| PBC | 0.238 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.670 | 0.818 | ||

| SM | 0.220 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.739 | 0.859 | |

| PI | 0.105 * | 0.224 ** | 0.137 ** | 0.483 | 0.680 | 0.824 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | β | p-Values | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EA-PI | 0.112 | *** | Accepted |

| H2 | SN-PI | 0.124 | 0.039 | Accepted |

| H3 | PBC-PI | 0.154 | *** | Accepted |

| H4 | SM-PI | 0.128 | 0.19 | Rejected |

| H5 | SM-EA | 0.406 | 0.01 | Accepted |

| H6 | SM-SN | 0.277 | *** | Accepted |

| H7 | SM-PBC | 0.245 | *** | Accepted |

| H8 | SM-EA-PI | 0.259 | *** | Accepted |

| H9 | SM-SN-PI | 0.201 | *** | Accepted |

| H10 | SM-PBC-PI | 0.199 | *** | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samaniego-Arias, M.; Chávez-Rojas, E.; García-Umaña, A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerrero-Haro, S.; Cando-Aguinaga, W. The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062706

Samaniego-Arias M, Chávez-Rojas E, García-Umaña A, Carrión-Bósquez N, Ortiz-Regalado O, Llamo-Burga M, Ruiz-García W, Guerrero-Haro S, Cando-Aguinaga W. The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062706

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamaniego-Arias, Mayra, Eva Chávez-Rojas, Andrés García-Umaña, Nelson Carrión-Bósquez, Oscar Ortiz-Regalado, Mary Llamo-Burga, Wilfredo Ruiz-García, Santiago Guerrero-Haro, and Wladimir Cando-Aguinaga. 2025. "The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062706

APA StyleSamaniego-Arias, M., Chávez-Rojas, E., García-Umaña, A., Carrión-Bósquez, N., Ortiz-Regalado, O., Llamo-Burga, M., Ruiz-García, W., Guerrero-Haro, S., & Cando-Aguinaga, W. (2025). The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Sustainability, 17(6), 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062706

_Li.png)