Exploring the Quality of Commercial Relations Between Producers and Buyers in the Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Background on Quality of Commercial Relations

3. Materials and Methods

- A qualitative analysis using focus groups, which aims to identify the factors that shape the producer-buyer commercial relation from the point of view of the POs;

- A quantitative analysis, where a survey is developed and administered to producers, with the aim to disclose the influence of these factors on the quality of the commercial relations they establish with buyers.

3.1. Focus Group

3.2. Survey

- -

- -

- -

- -

- D4 “Relational quality and trust”, summarizing the degree of mutual trust, good personal relations, and transparency of communication between supplier and buyer [6], expressed by F10, F11, F12;

- -

- -

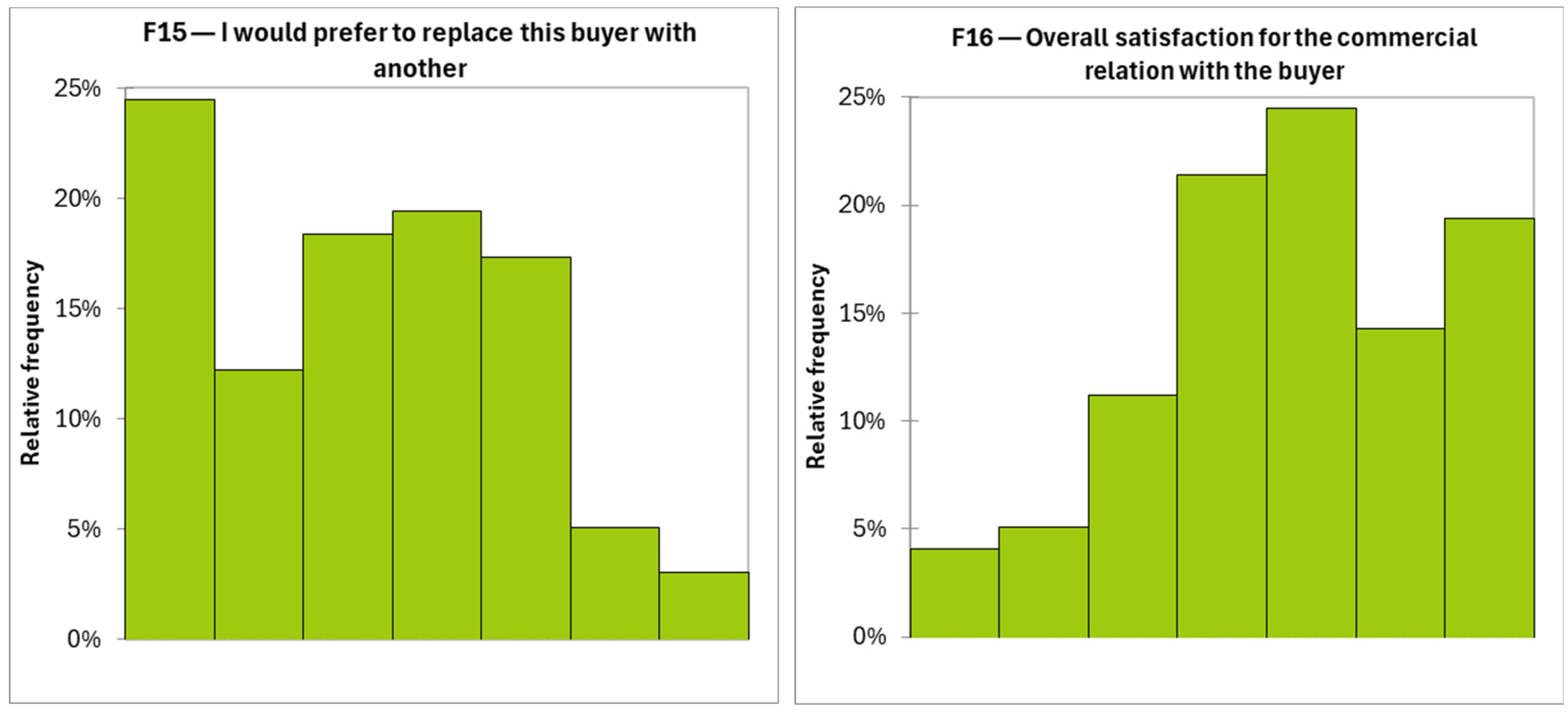

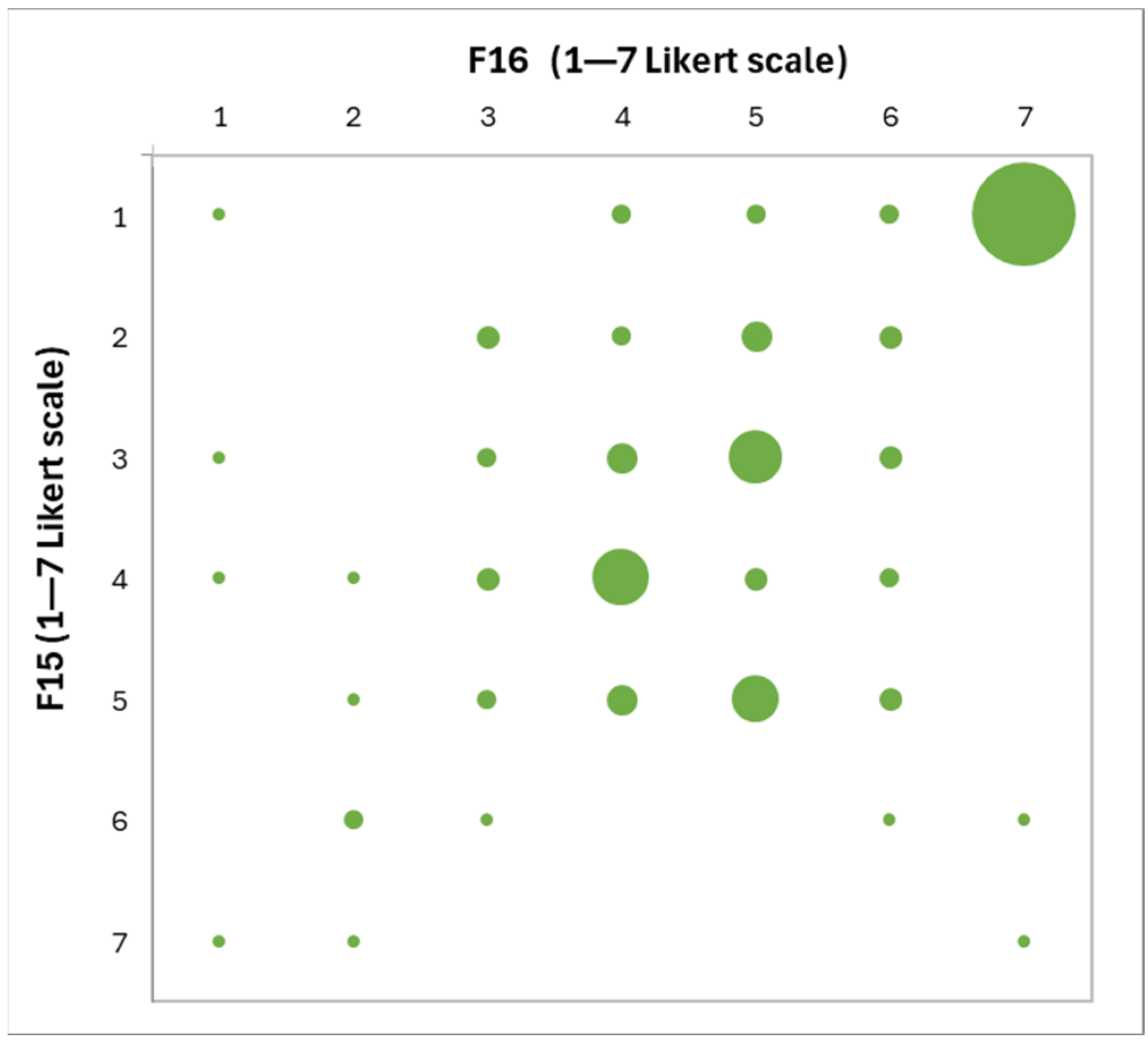

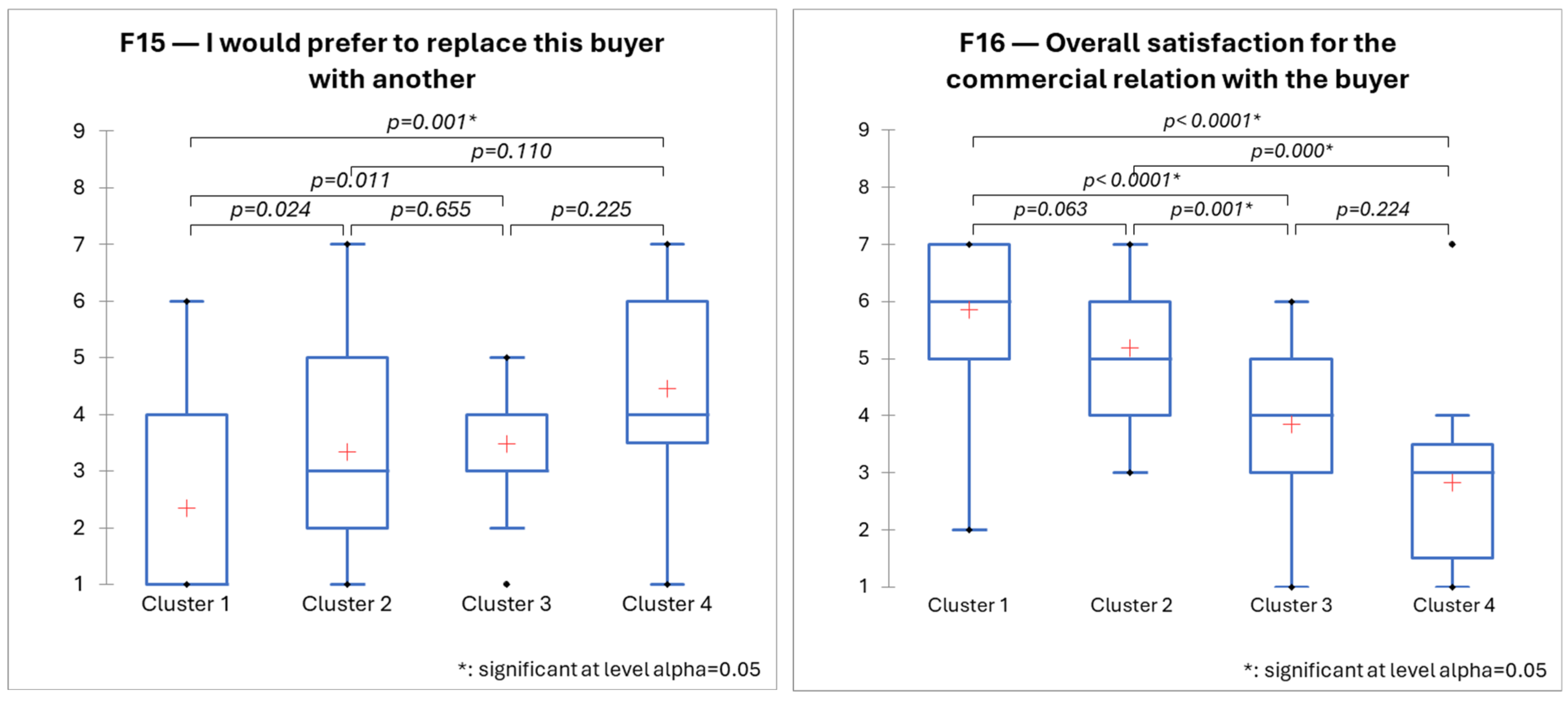

- F15: “In the next 2–3 years, I would prefer to replace this buyer with another”

- -

- F16: “Overall, I am satisfied with the commercial relations with this buyer”

4. Results

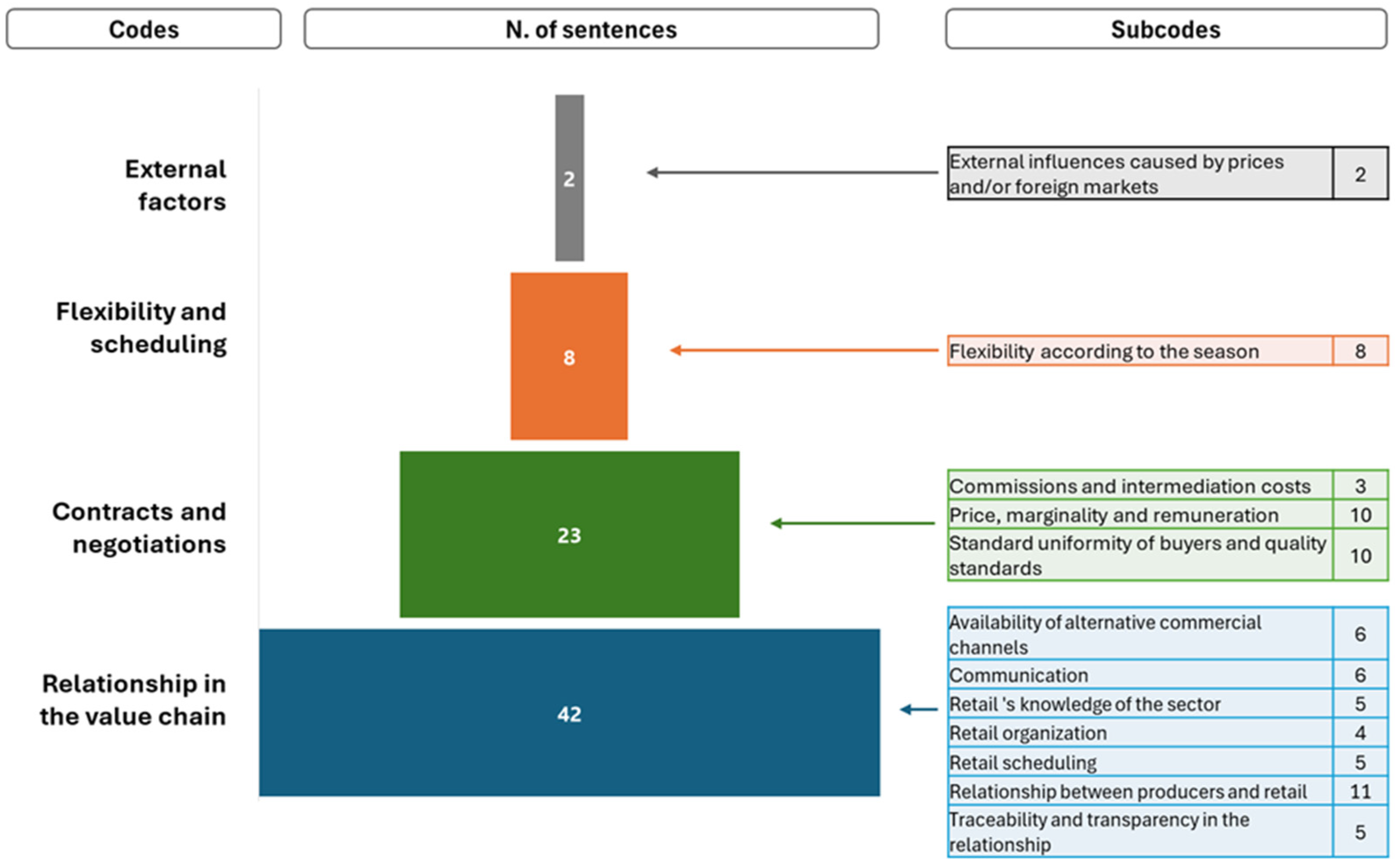

4.1. Results of the Focus Group

4.2. Results of the Survey

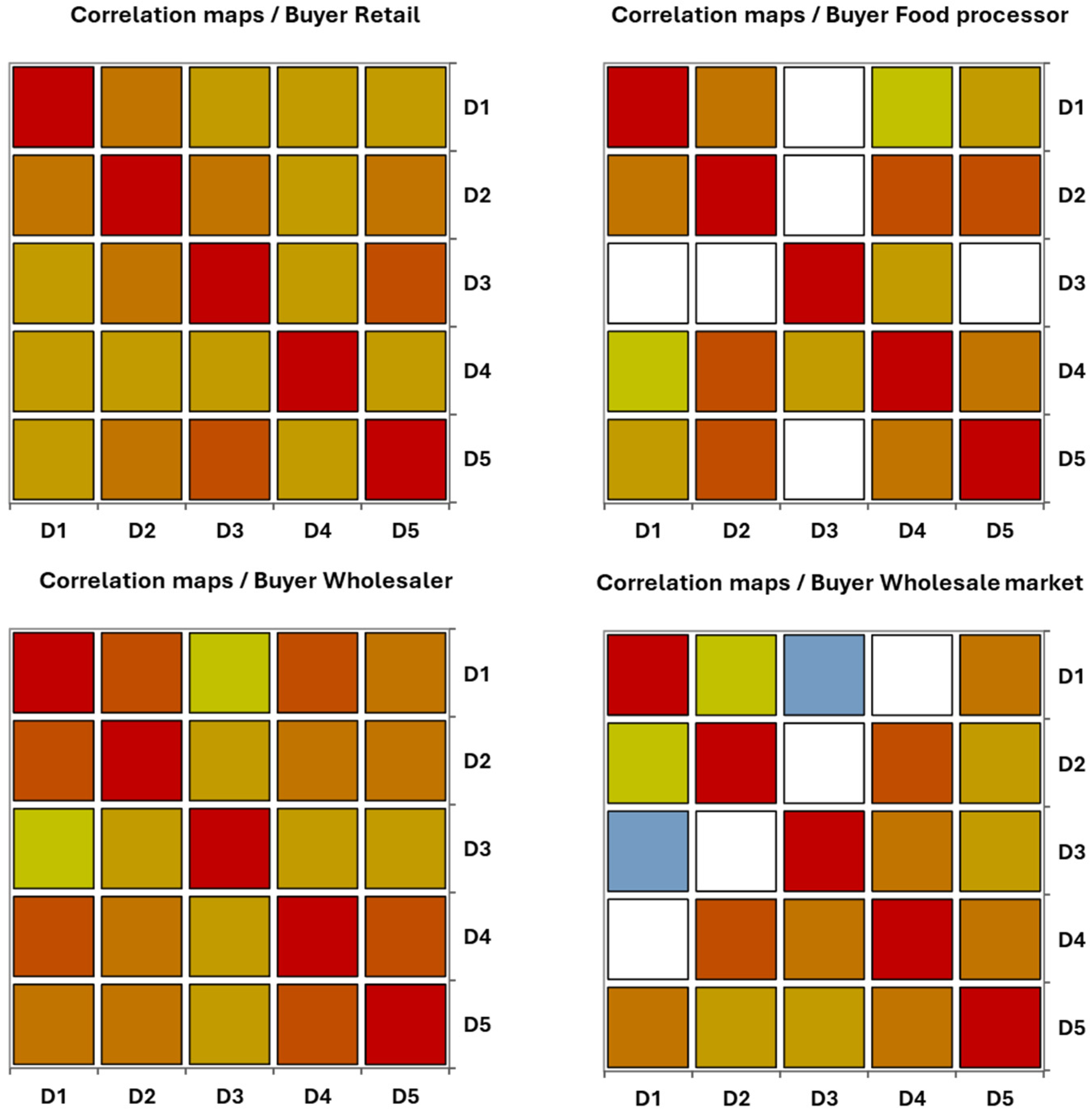

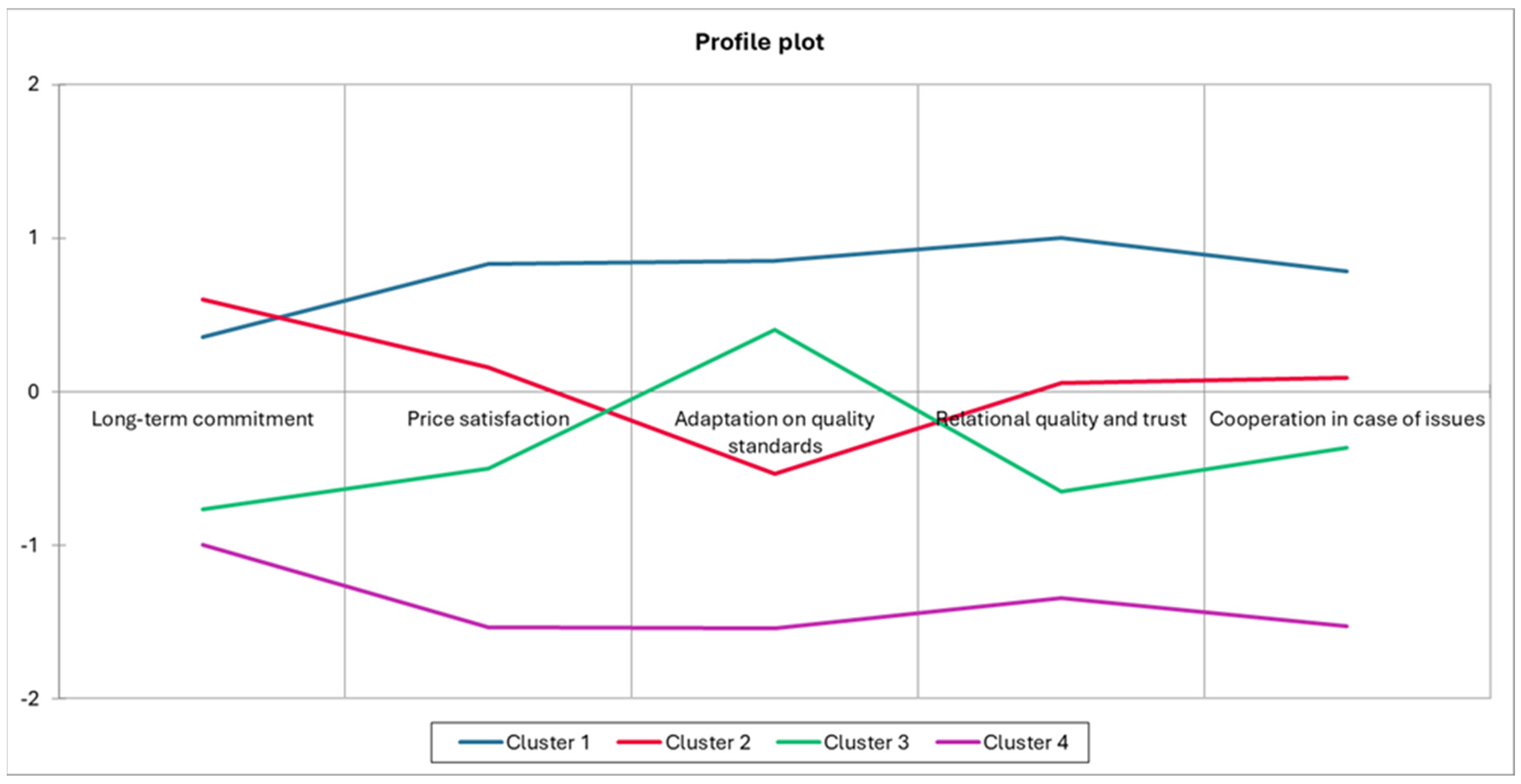

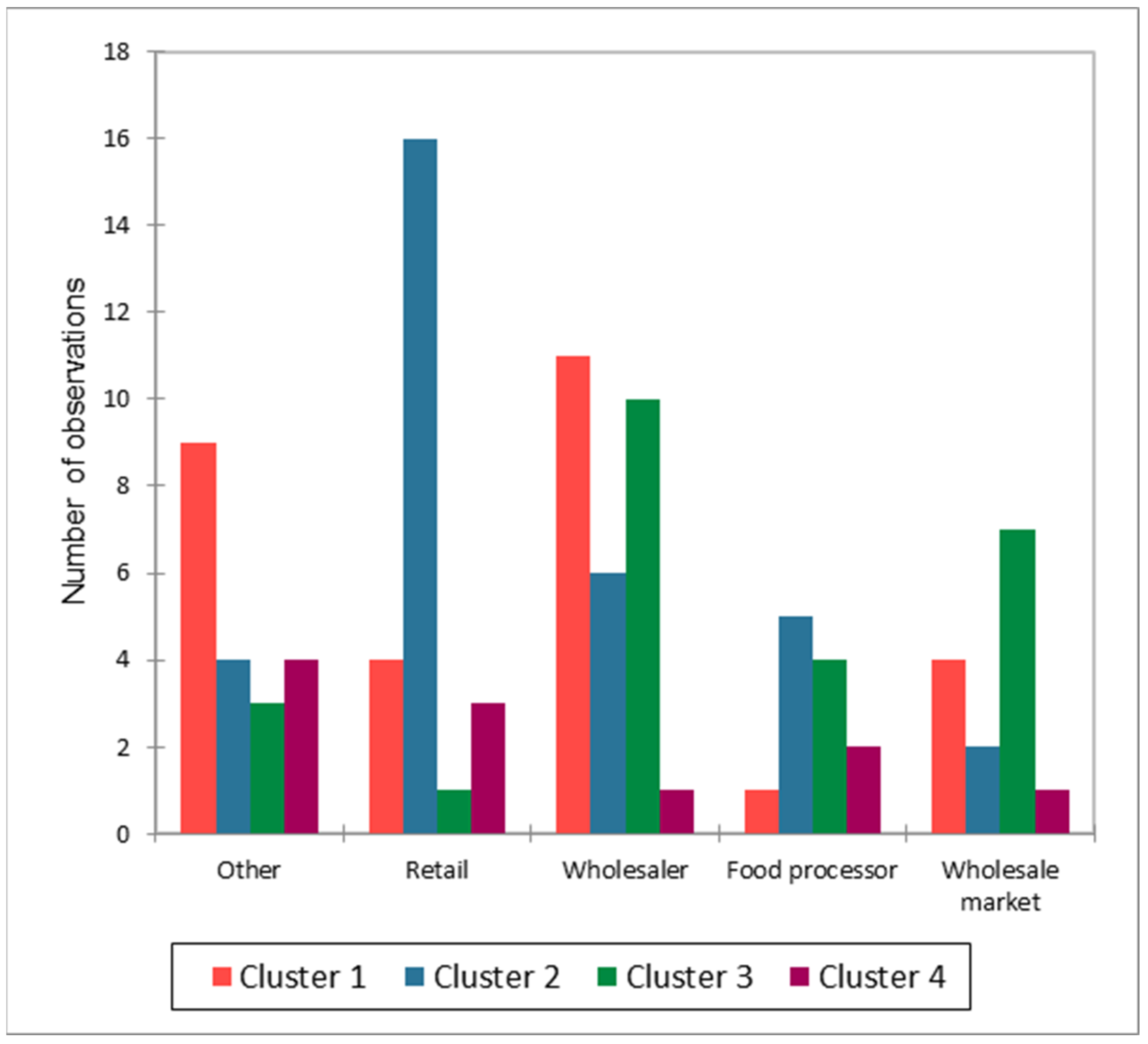

4.2.1. Cluster Analysis with Aggregate Variables

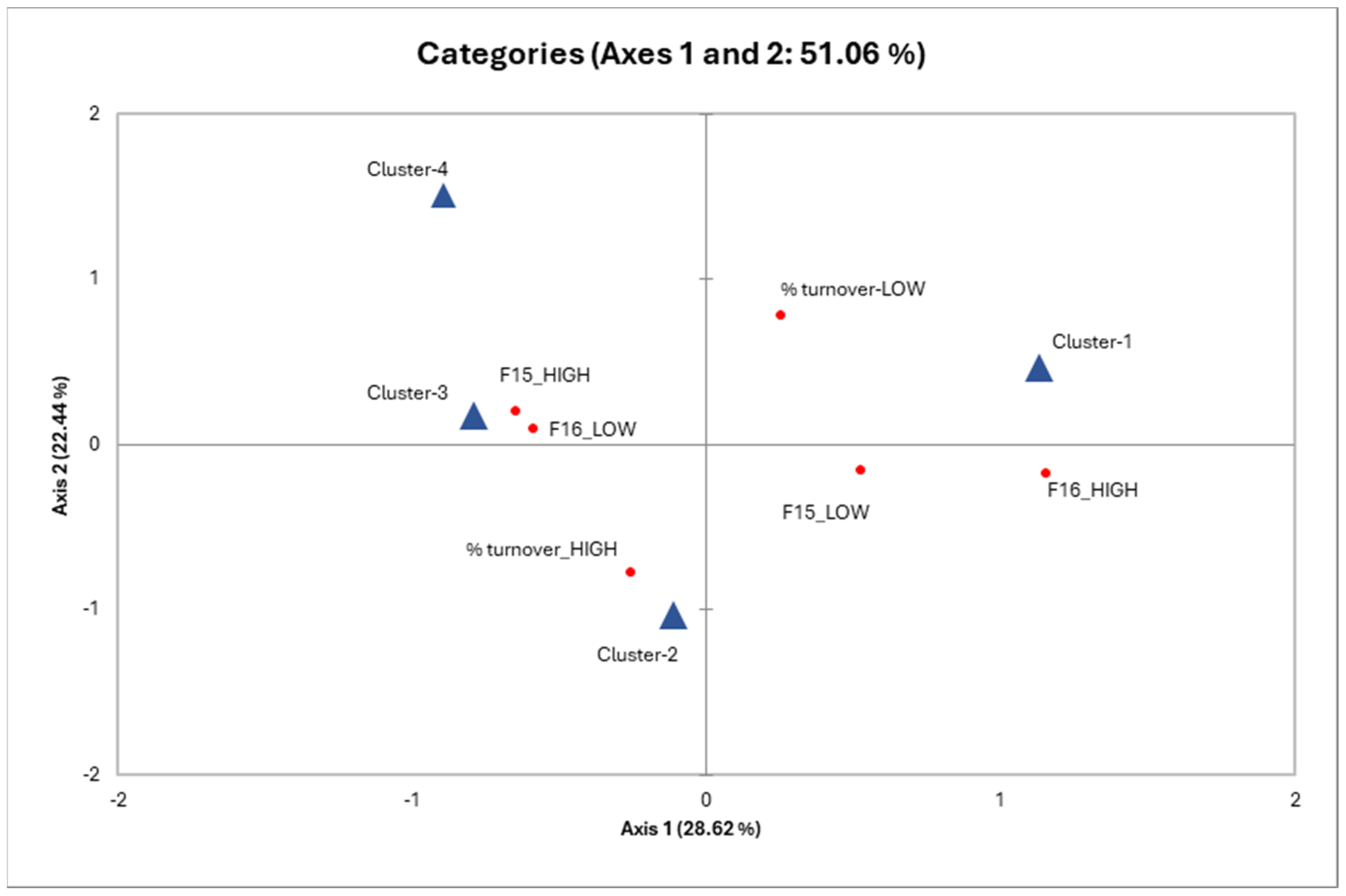

4.2.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PO(s) | Producer Organisation(s) |

| UTP(s) | Unfair Trading Practice(s) |

References

- Bonanno, A.; Russo, C.; Menapace, L. Market power and bargaining in agrifood markets: A review of emerging topics and tools. Agribusiness 2018, 34, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, R.J.; Xia, T. Increasing concentration in the agricultural supply chain: Implications for market power and sector performance. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A. Foods and places: Comparing different supply chains. Agriculture 2018, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, B.; Gellynck, X.; Weaver, R.D. The influence of relationship quality on the innovation capacity in traditional food chains. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.M.; Abdi, M.; Amirnequiee, S.; Ghasemi, R. The impact of supply chain relationship quality and cooperative strategy on strategic purchasing. J. Logist. Manag. 2016, 5, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdić, D.; Mesić, Ž.; Petljak, K. Preliminary research about producers’ perceptions of relationship quality with retailers in the supply chain of organic food products in Croatia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, R.; Schmidt, T.; Keck, M. Market power and food loss at the producer-retailer interface of fruit and vegetable supply chains in Germany. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 2253–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondliwa, P.; Roberts, S.; Ponte, S. Competition and power in global value chains. Compet. Change 2021, 25, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangeli, R.; Herzberg, R.; Cicatiello, C.; Schneider, F. Quality Standards and Contractual Terms Affecting Food Losses: The Perspective of Producer Organisations in Germany and Italy. Foods 2023, 12, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, B.; Richards, C. Food waste, power, and corporate social responsibility in the Australian food supply chain. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorbiansky, S.R.; Ellison, B. Contracting and quality standards in fresh produce markets and how they impact food loss. In The Economics of Food Loss in the Produce Industry; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 250–262. [Google Scholar]

- Corrado, A.; Caruso, F.S.; Lo Cascio, M.; Nori, M.; Palumbo, L.; Triandafyllidou, A. Is Italian Agriculture a ‘Pull Factor’for Irregular Migration—And, If So, Why? 2018. Available online: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/uploads/ba12312d-31f1-4e29-82bf-7d8c41df48ad/is-italian-agriculture-a-pull-factor-for-irregular-migration-20181205.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Cacchiarelli, L.; Sorrentino, A. Market power in food supply chain: Evidence from Italian pasta chain. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Russo, C.; Cacchiarelli, L. Market power and bargaining power in the EU food supply chain: The role of Producer Organizations. New Medit 2018, 17, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, M.P.; Ponte, S.; Sturgeon, T.J. Power in global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2019, 26, 666–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, J.; Ménard, C.; Sexton, R.; Swinnen, J.; Vandevelde, S.; Di Marcantonio, F.; Ciaian, P. (Eds.) Unfair Trading Practices in the Food Supply Chain: A Literature Review on Methodologies, Impacts and Regulatory Aspects; EUR 28791 EN; JRC108394; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-73831-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Commission. EU Regulation 2013/1308 and the Commission Delegated Regulation 2016/232; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, C.; Di Marcantonio, F.; Cacchiarelli, L.; Menapace, L.; Sorrentino, A. Unfair trading practices and countervailing power. Food Policy 2023, 119, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, R.D. The role of farmer cooperatives in a changing agricultural economy. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1987, 19, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU 2013 EU. Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 Establishing a Common Organisation of the Markets in Agricultural Products and Repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No1037/2001 and (EC)No1234/2007. 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32013R1308 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development; Montanari, F.; Chlebicka, A.; Szabo, G.; Amat, L.; Traon, D.; Sorrentino, A.; Russo, C.; Ferreira, I. Study of the Best Ways for Producer Organisations to be Formed, Carry out Their Activities and Be Supported—Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2762/034412 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Van Herck, K. Assessing Efficiencies Generated by Agricultural Producer Organizations (No. 473441); KU Leuven, Faculty of Economics and Business (FEB), LICOS-Centre for Institutions and Economic Performance: Leuven, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://bookshop.europa.eu/it/assessing-efficiencies-generated-by-agricultural-producer-organisations-pb-KD0214739/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Nucera, M.; Ferrari, G.M.; Finizia, A.; Merciai, S.; Sorrentino, A. The role of Producer Organisations in the vegetable value chain: An application to the red chicory from Veneto. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2016, 71, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, B.; Buffaria, B.; European Commission. About farmers’ bargaining power within the new CAP. Agric. Food Econ. 2017, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, A.; Van Lembergen, K.; Tarantini, F.; Heene, A.; Gellynck, X. Price transparency as a prerequisite for fair competition: The case of the European food prices monitoring tool. In The Ethics and Economics of Agrifood Competition; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, D. Detecting market power along food supply chains: Evidence and methodological insights from the fluid milk sector in Italy. Agriculture 2018, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, S.; Leckie, C.; Lobo, A.; Hewege, C. Power and relationship quality in supply chains: The case of the Australian organic fruit and vegetable industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, B.; Wocken, C.; Spiller, A. Relationship quality in agri-food chains: Supplier management in the German pork and dairy sector. J. Chain. Netw. Sci. 2006, 6, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.B. The Transaction—Relationship Dichotomy in Logistics and Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2005, 6, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I.; Steenkamp, J.B.E. Economic and social satisfaction: Measurement and relevance to marketing channel relationships. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative content analysis: From Kracauer’s beginnings to today’s challenges. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2019, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, G.T.; Achrol, R.S.; Mentzer, J.T. The structure of commitment in exchange. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, H.; IMP Project Group. International Marketing and Purchasing of Industrial Goods: An Interaction Approach; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, X. Examining the impact of market power discrepancy between supply chain partners on firm financial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 268, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghosh, R.; Mattsson, L.; Ismatov, A. Take-back agreements in the perspective of food waste generation at the supplier-retailer interface. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasso, M.; Blasi, E.; Pezzoli, F.; Cicatiello, C. Investigating Co-Innovation strategies to prevent food loss in the fruits and vegetables sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 467, 142984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giua, C.; Materia, V.C.; Camanzi, L. Smart farming technologies adoption: Which factors play a role in the digital transition? Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzato, D.; Gatto, P.; Defrancesco, E.; Bortolini, L.; Pirotti, F.; Pisani, E.; Sartori, L. The role of factors affecting the adoption of environmentally friendly farming practices: Can geographical context and time explain the differences emerging from literature? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Galli, F.; Barjolle, D.; Van Broekhuizen, R.; Colombo, L.; Giampietro, M.; Kirwan, J.; Lang, T.; Mathijs, E.; Maye, D.; et al. Are local food chains more sustainable than global food chains? Considerations for assessment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, M.T.; Lucas, M.R.; Rainho, M.J.M. A meta-analysis on the trust in agrifood supply chains. Food Front. 2022, 3, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanzi, L.; Malorgio, G.; Azcárate, T.G. The role of producer organizations in supply concentration and marketing: A comparison between European countries in the fruit and vegetable sector. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2011, 17, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Alpmann, J.; Bitsch, V. Exit, voice, and loyalty in the case of farmer associations: Decision-making of dairy farmers during the German milk conflict. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, R.; Trebbin, A.; Schneider, F. Product specifications and business practices as food loss drivers—A case study of a retailer’s upstream fruit and vegetable supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangeli, R.; Cicatiello, C. Lost vegetables, lost value: Assessment of carrot downgrading and losses at a large producer organisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Zamudio, M.A.; Barco, H.; Schneider, F. Direct measurement of mass and economic harvest and post-harvest losses in Spanish persimmon primary production. Agriculture 2020, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, S.; Herrero, L.G.; Burgos, S.; Colin, F.; Gheoldus, M.; Ledoux, C.; Parfitt, J. Unfair Trading Practice Regulation and Voluntary Agreements Targeting Food Waste. A Policy Assessment in Select EUMember States. REFRESH. 2018. Available online: https://eu-refresh.org/unfair-trading-practice-regulation-and-voluntary-agreements-targeting-food-waste.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Sinclair Taylor, J.; Parfitt, J.; Jarosz, D. Regulating the Role of Unfair Trading Practices in Food Waste Generation. 2019. Available online: https://eu-refresh.org/sites/default/files/REFRESH%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20UTPs_2019_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

| Num | Region (Noth, Centre, Sud) | Range of Tunover (€ per Year) | Last Available Data on Total Activity (€) | Number of Employees | Presence/Online |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North | <10 mln € | 2023 | 7 | O |

| 2 | Centre | <10 mln € | 2022 | 15 | P |

| 3 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 93 | O |

| 4 | South | <10 mln € | 2022 | 23 | O |

| 5 | South | <10 mln € | 2022 | 106 | O |

| 6 | South | >20 mln € | 2022 | 158 | O |

| 7 | Centre | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 2 | P |

| 8 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 154 | O |

| 9 | South | <10 mln € | 2021 | 57 | O |

| 10 | Centre | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 212 | P |

| 11 | Centre | <10 mln € | 2023 | 11 | O |

| 12 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 28 | O |

| 13 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2021 | 4 | O |

| 14 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2021 | 71 | O |

| 15 | South | <10 mln € | 2022 | 3 | O |

| 16 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 8 | O |

| 17 | Centre | <10 mln € | 2022 | 140 | O |

| 18 | North | <10 mln € | 2021 | 3 | O |

| 19 | South | >20 mln € | 2022 | 73 | O |

| 20 | South | >20 mln € | 2021 | 95 | O |

| 21 | North | >20 mln € | 2023 | 101 | O |

| 22 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 91 | O |

| 23 | South | <10 mln € | 2022 | 1 | O |

| 24 | South | 10–20 mln € | 2022 | 105 | O |

| Cod | Dim. | Variable | Units | Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | D1 | This buyer gives me the certainty of being able to sell a large part of my production | Likert 1–7 | 4.48 | 1.81 | 1 | 7 |

| F2 | D1 | This buyer gives me the certainty of having a medium–long-term sales channel | Likert 1–7 | 4.57 | 1.53 | 1 | 7 |

| F3 | D1 | With this buyer, the contractual conditions are clear from the beginning of the season | Likert 1–7 | 4.1 | 1.84 | 1 | 7 |

| F4 | D2 | This buyer offers me good prices for my products | Likert 1–7 | 4.16 | 1.45 | 1 | 7 |

| F5 | D2 | This buyer gives me the possibility of making good margins on the products | Likert 1–7 | 4.1 | 1.55 | 1 | 7 |

| F6 | D3 | The quality standards (aesthetic aspects, size, shape, color, etc.) required by this buyer are strict (compared with others) | Likert 1–7 | 4.81 | 1.67 | 1 | 7 |

| F7 | D3 | The control of quality standards upon delivery is rather flexible | Likert 1–7 | 3.86 | 1.61 | 1 | 7 |

| F8 | D3 | It often happens that the products we deliver to this buyer are rejected | Likert 1–7 | 3.48 | 1.68 | 1 | 7 |

| F9 | - | The buyer does not appropriately consider the uncertainty of the weather and seasonal conditions of the last period | Likert 1–7 | 4.39 | 1.91 | 1 | 7 |

| F10 | D4 | There is no dialogue with this buyer | Likert 1–7 | 3.68 | 1.82 | 1 | 7 |

| F11 | D4 | I have a good relationship with the person with whom I contract the sale of the products | Likert 1–7 | 4.72 | 1.61 | 1 | 7 |

| F12 | D4 | This buyer considers us to be reliable | Likert 1–7 | 5.35 | 1.43 | 1 | 7 |

| F13 | D5 | If we make a mistake, this buyer is available to help us out. | Likert 1–7 | 4.39 | 1.55 | 1 | 7 |

| F14 | D5 | If they (the buyer) make a mistake, they are willing to fix it | Likert 1–7 | 4.28 | 1.68 | 1 | 7 |

| F15 | I would prefer to replace this buyer with another | Likert 1–7 | 3.19 | 1.66 | 1 | 7 | |

| F16 | Overall, I am satisfied with the commercial relations with this buyer | Likert 1–7 | 4.76 | 1.61 | 1 | 7 |

| Variable | Type of Categories | Category | Description | Observations % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the farmer joining a PO or a cooperative | Dummy | 0 | No | 42.55 |

| 1 | Yes | 57.45 | ||

| Localization in Italy | Categorical | 1 | North | 26.60 |

| 2 | Centre | 41.49 | ||

| 3 | South | 31.91 | ||

| Which is the commercial channel? | Categorical | 1 | Retailers | 24.47 |

| 2 | Wholesalers | 27.66 | ||

| 3 | Food processors | 12.77 | ||

| 4 | Wholesale markets | 14.89 | ||

| 5 | Other (specify | 20.21 | ||

| % of turnover with the buyer | Dummy | 0 | <40% of the total turnover | 50.00 |

| 1 | >40% of the total turnover | 50.00 | ||

| How many years have you been working with this buyer? 1 | Categorical | 1 | less than 2 years | 9.57 |

| 2 | Between 2 and 5 | 27.66 | ||

| 3 | Between Tra 5 and 10 | 12.77 | ||

| 4 | More than 10 | 50.00 | ||

| F15—I would prefer to replace this buyer with another | Dummy | 0 | Lower than the median value | 55.10 |

| 1 | Higher than the median value | 44.89 | ||

| F16—Overall, I am satisfied with the commercial relations with this buyer | Dummy | 0 | Lower than the median value | 66.33 |

| 1 | Higher than the median value | 33.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pietrangeli, R.; Cicatiello, C.; Galli, F.; Carbone, A.; Cacchiarelli, L.; Sorrentino, A.; Russo, C. Exploring the Quality of Commercial Relations Between Producers and Buyers in the Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chain. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062641

Pietrangeli R, Cicatiello C, Galli F, Carbone A, Cacchiarelli L, Sorrentino A, Russo C. Exploring the Quality of Commercial Relations Between Producers and Buyers in the Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chain. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062641

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrangeli, Roberta, Clara Cicatiello, Francesca Galli, Anna Carbone, Luca Cacchiarelli, Alessandro Sorrentino, and Carlo Russo. 2025. "Exploring the Quality of Commercial Relations Between Producers and Buyers in the Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chain" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062641

APA StylePietrangeli, R., Cicatiello, C., Galli, F., Carbone, A., Cacchiarelli, L., Sorrentino, A., & Russo, C. (2025). Exploring the Quality of Commercial Relations Between Producers and Buyers in the Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chain. Sustainability, 17(6), 2641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062641