Abstract

Climate change is one of the most urgent issues of our time. Its increasingly visible effects make it a global worry and a chronic stressor, especially for specific developmental targets such as young adults. This study outlines the process of the Italian adaptation and validation of the Climate Change Coping Scale (CCCS), an instrument that examines three distinct coping strategies for addressing climate change. Study I, conducted with a sample of 230 Italian young adults (42.6% males; 57.4% females), explores the latent structure of the instrument using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Parallel Analysis (PA) and outlines the preliminary psychometric properties of the CCCS. A distinct sample of 500 Italian young adults (38.6% males; 61.4% females) was selected for Study II, which presents the results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), supporting a first-order factor structure with three correlated dimensions. These dimensions, as in the original scale, are labeled ’Meaning-Focused Coping’ (five items), ’Problem-Centered Coping’ (five items), and ’De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping’ (six items). The internal reliability of the CCCS, the measurement of invariance between males and females, and its discriminant and convergent validity are also described. Finally, significant differences in the levels of the three identified coping strategies are presented and discussed in relation to sociodemographic variables, including gender, political orientation, occupational and relationship status, and participation in environmental organizations. Overall, the results of Studies I and II highlight the reliability, validity, and robustness of the Italian version of the Climate Change Coping Scale.

1. Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [1] has identified climate change as one of the most critical global challenges that humanity is facing. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events in various regions of the world, the emergence of new infectious diseases, the disruption of food systems, and the growing uninhabitability of large geographic areas have made it an increasingly tangible and visible threat [2,3]. In Europe, temperatures are rising steadily at a rate surpassing the global average, as are extreme weather events and mortality rates associated with air pollution [4]. In recent years, the Mediterranean region—the geographic context of this study—has been particularly affected by climate change [3]. In Italy alone, 351 extreme weather events were recorded in 2024, marking a 485% increase compared to 2015 [5].

In fact, scientific research has recognized climate change as a significant risk factor for both physical and community health [6,7,8,9] and as a chronic stressor that individuals must confront [10]. Its scale, uncontrollability, and unpredictability heighten the perceived threat, contributing to negative psychological states [11,12]. In other words, the issue is not solely environmental, but also sociological and psychological, with profound implications for mental well-being [13]. This distress is particularly pronounced among individuals in transitional developmental stages, such as young adults between the ages of 18 and 30, who are already affected by collective traumatic events or those that could potentially become so [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

For this reason, awareness of climate change is increasing among young people in various parts of the world [28] and, in Italy, this phenomenon represents one of their primary present and future worries [29,30]. Indeed, young adulthood is a phase of the life cycle characterized by significant developmental transitions, such as the completion of studies, entry into the workforce, and the beginning of building one’s independence. Young adulthood is considered a vulnerable target group for the psychological and social impacts of the climate crisis, which fuels anxiety and worries [30]. As highlighted in the literature, coping strategies related to the climate threat influence the adoption of sustainable behaviors and psychological well-being [31,32,33]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the strategies employed by young adults to cope with one of their greatest worries: the climate crisis.

1.1. Coping: Strategies for Dealing with Stressful Situations

Coping strategies are defined as “cognitive and/or behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised by the individual as threatening, stressful, or potentially harmful, either in the present or the future” [34]. This process begins with the evaluation of a stimulus or event, which is perceived as stressful when it exceeds individual resources available for coping [35]. Initially, Lazarus and Folkman [34] distinguished two broad categories of coping strategies: “problem-focused coping” and “emotion-focused coping”, which have since been understood as complementary and integrated [36]. The previous literature categorizes the strategies aimed at modifying or directly managing the source of stress under the term “problem-focused coping”. These include actions such as breaking down tasks into smaller steps, seeking information to better understand the stressor, or acquiring new skills to address or eliminate the stressor. These strategies are considered adaptive and functional when dealing with controllable and resolvable situations and often improve mental well-being [34,37]. On the other hand, “emotion-focused coping” encompasses strategies and actions that aim to manage and regulate the negative emotions evoked by a stressful situation without directly addressing the stressor itself [34]. Examples include self-soothing, expressing negative emotions, denial, or avoiding the threat. These strategies are typically activated in response to stressors perceived as uncontrollable or distant and are often linked to lower mental well-being [38,39].

More recently, Folkman [40] expanded the concept of “emotion-focused coping” by introducing the notion of “meaning-focused coping”. This category includes mental and behavioral processes aimed at fostering positive emotions and feelings in the face of stressful situations, allowing for a reappraisal of the stressor through the use of personal values and beliefs, and the identification of potential benefits. This approach emerged as an important protective factor for psychological well-being [40,41].

In the conceptualization of coping strategies, research has integrated both situational and dispositional perspectives [42,43] demonstrating that the choice of coping strategy is influenced not only by dispositional factors but also by situational variables, such as the individual’s appraisal of the stressor [44].

1.2. From a General Definition of Coping to Coping with Climate Change

Following the distinction made by Lazarus and Folkman [34], individuals facing the climate crisis can adopt problem-focused strategies, such as discussing the issue with friends and family, seeking information, or engaging in environmentally protective behaviors [45]. This approach is associated with a heightened awareness of the risks posed by climate change [33], which can motivate individuals to change their lifestyle by reducing their ecological footprint through actions such as using sustainable transportation, reducing energy waste, or engaging in recycling [45]. However, studies on global-scale social issues, such as wars, terrorism, or climate change, as well as problem-focused coping strategies, have yielded mixed results. While the adoption of such strategies can foster self-efficacy, behavioral engagement, and sometimes psychological well-being [34,37,46,47], their continued use is often associated with lower psycho-physical well-being and increased distress [32,47,48,49].

On the other hand, the uncontrollability of climate change, its global nature, and the difficulty of finding rapid solutions also increase negative emotions. These emotions can activate emotion-focused coping strategies aimed at denying, avoiding, or downplaying the problem through egocentric thinking or daydreaming [45]. Disengaging from climate change or perceiving the threat as exaggerated can be a strategy to avoid both negative emotions and the effort required to focus on or act against it [35,50,51]. Research has shown that emotion-focused strategies reduce distress levels and play a protective role in psychological well-being, but they also negatively affect pro-environmental behaviors [32,52,53]. As a result, these strategies are conceptualized as detrimental to environmental engagement and sustainable actions [54].

Furthermore, previous studies have highlighted that values, personal beliefs, and existential goals can prompt adaptive strategies that help preserve awareness of the magnitude of this macro-social stressor by focusing on the positive reappraisal of climate change, as well as on trust and hope [45]. These approaches belong to meaning-focused coping and assume particular relevance in addressing the climate threat, as they foster positive emotions that protect well-being, as also noted by Park and Folkman [55]. In a nutshell, placing the climate issue within its historical context, adaptive strategies such as maintaining trust in social actors (viz. scientists, politicians, environmental organizations, and humanity as a whole), and believing in a global change seem to not only mitigate excessive concern and the sense of helplessness potentially generated by problem-focused strategies but also promote both psychological well-being and sustainable actions [56,57,58,59].

To date, and particularly in the context explored in the present study, few studies have examined coping strategies concerning climate change. As a matter of fact, to our knowledge, there are no valid and reliable specific tools designed for this purpose. However, the importance of coping strategies in exploring the psychological determinants implicated in climate change has been widely acknowledged [31,33,45,51,60]. Therefore, it is crucial to further investigate this urgent area and provide the scientific community with a robust and reliable tool for assessing coping strategies associated with climate change.

1.3. The Climate Change Coping Scale

Building upon three qualitative studies that carefully collected and analyzed original narrative material from semi-structured interviews, we identified several coping strategies for environmental issues in young people [57,58,59]. The narrative excerpts revealed various recurring strategies consistent with the literature on meaning-focused coping [40]. For example, many young people frequently use the strategy of positive reappraisal of environmental problems, which supports hope, the historical contextualization that fosters an increased awareness of the climate crisis, and trust in the social actors responsible for managing it. At the same time, the interviewees managed their concerns about climate change with strategies involving active behaviors, such as seeking information and engaging in pro-environmental actions. These strategies, characteristic of problem-focused coping [34], were not only associated by the participants with self-efficacy and environmental engagement but also with enhanced psychological well-being. Furthermore, in line with the concept of emotion-focused coping [34], it was found that the uncertainty, uncontrollability, and complexity of environmental issues, which triggered pervasive negative emotions, were managed using strategies aimed at reducing their impact on mental well-being [59]. Common strategies adopted to mitigate and counteract the negative emotions generated by climate change included minimizing the threat or perceiving it as irrelevant to one’s context, disengaging from climate change, or considering it an exaggerated problem [59].

Building on these qualitative studies, the first version of the Climate Change Coping Scale was developed by Ojala in 2012 (Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden) [45]. Originally consisting of 15 items, the scale explored three types of coping strategies: meaning-focused coping (e.g., “I have faith in humanity; we can fix all problems” or “I trust scientists to come up with a solution in the future”), problem-focused coping (e.g., “I search for information about what I can do” or “I talk with my family and friends about what one can do to help”), and de-emphasizing/avoidance coping (e.g., “I think that the problem is exaggerated” or “Climate change does not concern those of us living in Sweden”). The factorial structure of the scale was tested using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) on two samples: the first with an average age of 12 years [45] and the second with an average age of 17.2 years [51]. The scale demonstrated a stable factor structure and good internal consistency. Furthermore, a 16-item version of the tool [45] was used in the Media Exposure, Climate Anxiety and Mental Health project [61] (MECAMH); English version available at https://osf.io/6n4rb/?view_only=d708efc61e6945a1bc02e037a3ccac96, accessed on 11 January 2024. A 15-item version (seven response anchors: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) was also used on a large sample with an average age of 40 years [62] (English version available at https://osf.io/95rcg?view_only=adef6f1b8aa44aeeac90645feb2309f4, accessed on 11 January 2024).

Given the significant impact that coping strategies have on sustainable actions and climate distress [31,45,51,60,62], and the lack of a reliable tool to measure them within the Italian context, the following pages present the adaptation and validation of the Climate Change Coping Scale (CCCS) in its 16-item version with seven response anchors (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree).

2. Steps and Aims of the Research Design

This article aims to describe the process of adapting and validating the Italian version of the Climate Change Coping Scale (CCCS) with young adults. The adaptation and validation process included several steps organized into two main phases, carried out in two distinct but naturally integrated studies. Study I details the process of translating a 16-item version of the CCCS into Italian and seeks to explore its latent structure while verifying its preliminary psychometric properties. This was necessary due to the scale’s original use in different cultural contexts, with a different age group, and in the absence of prior confirmation of its latent structure. Study II aimed to confirm the factor structure of the CCCS identified in the previous study, using a second, independent sample of Italian young adults. At the same time, this study further examined the psychometric properties of the CCCS by assessing its internal consistency and measurement invariance by gender, as well as its convergent and discriminant validity.

3. Study I

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Italian Adaptation of the Climate Change Coping Scale

The author of the original version of the scale formally approved the translation and psychometric validation process. The back-translation method was employed to develop the Italian version of the scale. In the initial phase, an Italian native speaker with advanced proficiency in English performed a preliminary translation of the original scale. An English native speaker then conducted a back-translation of the scale from Italian into English. Subsequently, two independent translation processes were undertaken by a sociolinguist and a professional translator, each working separately on the preliminary Italian version of the tool. Afterward, both versions were compared, and consensus was reached regarding the final Italian version. The translation of the items into Italian preserved a straightforward syntactic structure, and no adjustments were made to accommodate specific regional dialects. Since the original English items were already characterized by simple syntax, the translation required only minimal modifications and adjustments.

3.1.2. Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined a priori using a ratio of a minimum of 10 participants per item [63,64]. Considering that the original scale consists of 16 items, a sample of at least 160 subjects would be sufficient to adequately test the preliminary latent configuration of the scale.

3.1.3. Participants and Procedure

For Study I, a group of 240 Italian young adults was recruited. The preliminary analysis of missing values and outliers revealed an absence of missing data and identified 20 cases with elevated Mahalanobis distances (p < 0.001), indicating the presence of potential multivariate outliers [65,66]. Each case was thoroughly examined through frequency histograms of responses and the minimum and maximum values for each item. This analysis uncovered 10 anomalous cases, where identical responses were provided for all items, which were subsequently removed to prevent their influence on subsequent analyses.

Finally, a sample of 230 Italian young adults was used (42.6% males; 57.4% females), aged 18 to 30 years (M = 22.59; SD = 3.00). During the data collection period, the majority of participants lived in southern Italy (92.6%), particularly in Campania (84.8%). The sociodemographic characteristics of this sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (Study I: N = 230).

Participants completed the Italian adaptation of CCCS and sociodemographic questions through an online survey conducted in May 2024. Individuals were recruited via convenience and snowball sampling methods, and those expressing interest in the study were asked to refer additional potential participants from their social networks. All participants were thoroughly informed about the study’s objectives, the confidentiality of the data collected, and the voluntary nature of their involvement. Participants provided informed consent on the first page of the survey and were prompted to respond with the utmost accuracy.

3.1.4. Data Plan Analysis

The first study preliminarily explored the latent structure of the instrument following cultural–linguistic adaptation using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Parallel Analysis (PA). This approach was adopted because a review of the literature revealed the absence of a prior confirmatory factor analysis of the instrument, which was originally developed for a slightly different target population with a distinct cultural background [67].

The suitability of items was evaluated with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO ≥ 0.80) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) [68]. In line with the original scale [45,51], EFA was performed using Principal Axis Factoring as the extraction method, with Direct Oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization. Eigenvalues ≥ 1.0, commonality ≥ 0.30, and factor loadings ≥ 0.50 for each item were selected as the criteria for the extraction and interpretation of factors. The Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA ≥ 0.50) was also assessed to evaluate the adequacy of the item pool in measuring the specific domain [69]. Optimized Parallel Analysis (PA) [70] was also implemented to further investigate the latent structure of the scale and to adjust the potential overestimation of the number of factors often associated with eigenvalues greater than 1. Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were calculated preliminarily to assess the internal consistency of the instrument and its dimensions. The Latent Hancock Index (H Index ≥ 0.80) was computed to evaluate how well the items of the tool reflect the latent variable, with a high probability of stability across multiple studies. Finally, complementary indices, including the Factor Determinacy Index (FDI; ≥0.90), EAP marginal reliability (≥0.80), Sensibility Ratio (SR; ≥2.0), and Expected Percentage of True Differences (EPTD; ≥90.0%) were calculated to test the quality and effectiveness of the factor solution.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS v. 29 [71] and Factor Analysis Program [72] [available at: https://psico.fcep.urv.cat/utilitats/factor/Download.html; accessed on 5 February 2025].

3.2. Results

Explorative Factor Analysis of the Italian Version of CCCS

The KMO value was 0.86 (95% CI [0.81; 0.87]), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 2599.25; df = 120; p < 0.001), indicating the adequacy of the data for factor analysis. As with the original scale, Principal Axis Factoring extracted three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, which collectively explained 70.43% of the variance. The eigenvalue for Factor 1, Problem-Centered Coping, was 5.87 (variance explained: 36.67%), while it was 3.43 for Factor 2, De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping (variance explained: 21.42%), and 1.97 for Factor 3, Meaning-Focused Coping (variance explained: 12.34%). This latent structure was further supported by the optimized Parallel Analyses (PA), which confirmed the significance of all three factors extracted. The results of the EFA and PA are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Explained variance based on eigenvalues and Parallel Analysis based on Minimum Rank Factor Analysis (N = 230).

As shown in Table 3, the item communalities were all greater than 0.30, ranging from 0.44 (item 1) to 0.85 (item 9). The items’ MSA values were all above 0.50, varying between 0.77 (item 1) and 0.92 (item 16). Factor loadings were statistically significant and loaded onto their respective first-order factors, ranging from 0.58 (item 3) to 0.93 (items 9 and 15).

Table 3.

Items factor loadings, communalities, and items’ MSA.

Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega for the items associated with Problem-Centered Coping (F1) were 0.93, respectively; for those associated with De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping (F2), they were 0.89 and 0.91, respectively; and for those associated with Meaning-Centered Coping (F3), they were 0.81 and 0.80, respectively. The latent H-index for Factor 1 was 0.94 (95% CI [0.92, 0.96]); it was 0.94 for Factor 2 (95% CI [0.88, 0.97]) and 0.82 for Factor 3 (95% CI [0.76, 0.85]). For Factor 1, the FDI was 0.97, marginal reliability was 0.94, SR was 4.13, and EPTD was 95.0%. For Factor 2, the FDI was 0.97, marginal reliability was 0.94, SR was 4.00, and EPTD was 94.7%. Finally, for Factor 3, the FDI was 0.91, marginal reliability was 0.82, SR was 2.15, and EPTD was 89.4%.

4. Study II

4.1. Materials and Methods

4.1.1. Sample Size Determination

As for Study I, a 10-to-1 subject-to-item ratio was employed to plan the minimum number of participants in advance, considering the data analysis to be conducted [63,64]. Additionally, we considered the guideline that 500 observations are deemed highly adequate for performing a confirmatory factor analysis [73].

4.1.2. Participants and Procedure

A total of 500 Italian young adults (38.6% males; 61.4% females), ranging in age from 18 to 30 (M = 22.84; SD = 3.04), were recruited for Study II. The greater part of participants resided in southern Italy (83.2%), with a particularly high concentration in Campania (76.6%). The sociodemographic characteristics of this sample are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (Study II: N = 500).

The preliminary analysis of the collected data revealed no missing values, and no statistically significant divergences were found regarding outliers [65,66]. This study included participants who were recruited in Italy through social media platforms, using self-report questionnaires administered via an online survey. Data collection for Study II occurred between June and September 2024. The questionnaire was promoted through posters displayed in social areas at the University of Naples, and, similar to the previous study, a snowball sampling technique was employed. Participants interested in the study were encouraged to refer to other potential respondents from their social networks. All participants were informed about the study’s objectives and the privacy and anonymity protocols regarding the collected data. Participation was voluntary, and individuals could withdraw from the study at any time. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: participants had to be between 18 and 30 years of age, reside in Italy, and provide consent to participate in the study on the initial page of the online questionnaire.

4.1.3. Instruments

In addition to the Italian version of the CCCS, the following tools were administered:

A socio-demographic section was included to collect information on participants’ age, gender, place of residence, type of dwelling, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, political affiliation, religious beliefs (specifically belief in God), and involvement in peace organizations (see Table 3).

The Climate Change Worry Scale (CCWS) [74,75] is a self-report instrument consisting of 10 items, each with a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Always). The scale is unidimensional and measures worry about climate change, a specific cognitive aspect of eco-anxiety, which is characterized by an excessive tendency to ruminate on climate change, primarily involving verbal-linguistic thoughts. The items aim to assess the awareness of worry regarding climate change, as well as concerns about one’s future and the future of loved ones, such as “Thoughts about climate change cause me to worry about what the future may bring” and “I realize that I often worry about climate change”. The Italian version of the scale, as demonstrated in its adaptation and validation study, exhibited strong psychometric properties and high internal consistency [75]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 and McDonald’s omega was 0.91.

The Integrated Pro-Environmental Behaviours Scale (I_PEBS) [76], a self-report instrument consisting of 18 items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). This instrument was designed to assess key pro-environmental behaviors related to climate change and is organized into six dimensions: Reduction of Waste (5 items), measuring behaviors aimed at reducing unnecessary waste (e.g., “Do you prefer reusable products over single-use items, such as bottles, straws, reusable bags, glass containers, etc.?”); Meat Consumption (3 items), assessing the reduction in the consumption of different types of meat (e.g., “How frequently do you consume pork products, such as pork ribs or sausages?”); Vegetable Consumption (3 items), focusing on the consumption of seasonal and organic plant-based foods (e.g., “Do you buy local plant-based food products?”); Environmental Activism (3 items), evaluating engagement and interest in climate-related issues (e.g., “How often have you participated in initiatives or events organized by environmental, conservation, or wildlife protection groups?”); Sustainable Clothing (2 items), exploring the recycling of clothing and the purchase of second-hand garments (e.g., “Do you use platforms such as Vinted for recycling clothes you no longer use?”); and Waste Segregation (2 items), assessing recycling behaviors (e.g., “Do you practice waste segregation?”). The original authors reported good psychometric properties of the instrument (Curcio et al., in review). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.70 and 0.69 for Reduction of Waste, 0.88 and 0.88 for Meat Consumption, 0.76 and 0.78 for Vegetable Consumption, 0.77 and 0.78 for Environmental Activism, 0.74 for Sustainable Clothing, and 0.60 for Waste Segregation.

The Snyder’s Dispositional Hope Scale (DHS) [77,78] is a self-report tool composed of a 12-item Likert scale with five points ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 5 (definitely true), which was used to measure the construct of hope as defined by Snyder (2000), viz. a positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of success (agency—goal-directed energy) and pathways (planning to meet goals). The scale is divided into two subdimensions: Agency and Pathways. The remaining items serve as fillers. The authors of the original scale reported good internal consistency [78]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.77 and 0.77 for the Pathways subdimension, and 0.77 and 0.77 for the Agency subdimension.

The Dark Future Scale (DFS) [79] is a self-assessment tool consisting of five items with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absolutely false) to 6 (absolutely true). This was used to assess Future Anxiety, a construct encompassing both the cognitive and emotional aspects when evaluating the attitude toward the future, where fear of the future predominates over hope. The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of Future Anxiety. The authors of the DFS report good internal consistency [79]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.88, and McDonald’s omega was 0.89.

The positive and negative emotions associated with climate change and related news were explored using a custom-designed tool, based on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [80]. Participants were asked to respond to the following question: “When you think about climate change or are exposed to news, images, and videos related to it, how do you feel?” On a scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always), participants were asked to respond to items related to Positive Emotions (six items: Calm, Optimistic, Determined, Reassured, Confident, Hopeful) and Negative Emotions (seven items: Helpless, Fearful, Sad, Worried, Guilty, Discouraged, Angry). The items associated with the “Positive Emotions” dimension showed good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 and McDonald’s omega of 0.86. Similarly, the items associated with the “Negative Emotions” dimension showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 and a McDonald’s omega of 0.85.

4.1.4. Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were initially conducted to explore means and standard deviations for each item. Skewness and kurtosis were evaluated to assess the data distribution. Multivariate normality was assessed by testing for skewness and kurtosis using Mardia’s tests [81]. Based on the EFA solution from Study I, a first-order model with three factors was specified. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with the robust maximum likelihood (MLM) estimator was used to verify the factorial structure of the CCCS. The MLM is a robust variant of the maximum likelihood estimator [82] that provides robust standard errors and is commonly used with the Satorra–Bentler chi-squared test (SBχ2) to assess model fit. Model fit was evaluated using different indices: the Chi-Squared statistic with degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). The following criteria were considered to indicate a good model fit: χ2/df ≤ 5.0; RMSEA and SRMR values ≤ 0.08, and CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.90 [83,84,85]. According to Comrey and Lee [86] 1992), standardized factor loadings were considered adequate if they were significant (p < 0.001) and greater than 0.50 (0.50 ≤ λ ≤ 0.62 = good; 0.63 ≤ λ ≤ 0.70 = very good; λ ≥ 0.70 = excellent).

Measurement invariance (MI) analyses were performed to test if the factor structure of CCCS was invariant between male and female participants. As a first step, the factor structure was constrained to be equal in the two groups (Model 1: Configural Invariance). Then, the factor loadings were constrained to be equal in the two groups (Model 2: Metric Invariance). Finally, in addition to the prior constraint, the intercepts were constrained to be equal in the two groups (Model 3: Scalar Invariance). The fit of these three models was tested using the aforementioned indices and cut-offs: χ2/df (≤ 5.0); CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90; RMSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.08. The assumption of invariance was assessed using DIFF SBχ2, ΔCFI (≤0.01), ΔTLI (≤0.01), and ΔRMSEA (≤0.015). As the χ2 statistic could be influenced more by the sample size and less by a lack of invariance [87], ΔCFI was evaluated as the preferred approach to assess measurement invariance. The instrument was considered invariant in the different models if at least two of the selected indices fell within the thresholds recommended in the literature [87].

Internal consistency and validity were also assessed. Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficients were used to evaluate reliability. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each latent construct was calculated to determine the amount of variance explained by each construct in relation to its corresponding observed variables. According to Hair et al. [88], it should be greater than 0.50. Discriminant validity (construct validity) was explored, evaluating the ability of the latent variable to differentiate itself from others within the model (Problem-Centered Coping, De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping, and Meaning-Centered Coping). According to the Fornell and Larcker criteria [89], the AVE should be greater than the shared variance between constructs assessed by the squared factor correlation. Then, convergent validity (construct validity) was calculated through Pearson’s correlations with other constructs theorized to be related to climate change coping strategies. Finally, the concurrent validity of CCCS was tested, selecting the Pro-Environmental behaviors as a possible outcome.

Finally, t-tests and ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests were conducted to examine sociodemographic differences (gender, occupational status, relationship status, political orientation, and course of study) in relation to climate change coping strategies. Effect sizes were measured using Cohen’s d (small ≤ 0.20; medium = 0.50; large ≥ 0.80; huge ≥ 1.0) and Eta-squared (η2; small ≥ 0.01; medium ≥ 0.059; large ≥ 0.138) (Cohen, 1988).

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 29 [71] and RStudio v. 4.4.1 (RStudio Team) [90], employing the Lavaan, Semtools, and Semplots packages

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

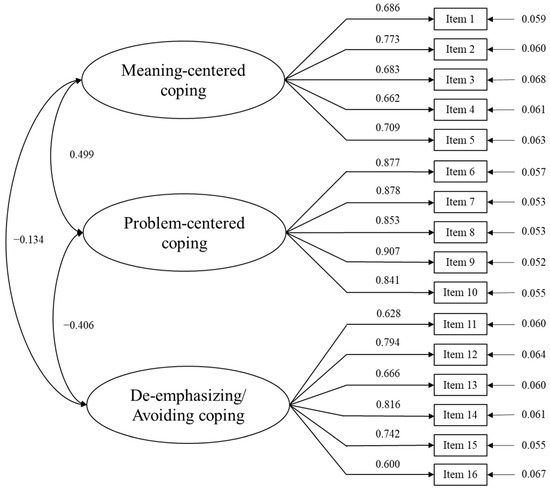

All descriptive information regarding items and dimensions is enclosed in Table 5. Mardia’s test did not show a significant finding for skewness (p > 0.05), whereas it was significant for kurtosis (p < 0.05), implying a slight deviation from normality in the data distribution. The first-order model with three factors fit the data well. Specifically, beyond the fact that the χ2 statistic was statistically significant, the other fit indices revealed a good model fit: SBχ2(101) = 316.992; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 3.14; CFI = 0.940 and TLI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.065 [CI: 0.059, 0.072] and SRMR = 0.061. As shown in Table 3, all standardized factor loadings were above the threshold of 0.60 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001) ranging from 0.600 (item 16) to 0.907 (item 9). Factor 1 showed a positive and significant association with Factor 2 (r = 0.499; p < 0.001) and a negative and significant association with Factor 3 (r = -0.134; p < 0.01). Finally, Factor 2 showed a negative significant association with Factor 3 (r = -0.406; p < 0.001). A graphical representation of the CCCS model is reported in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Item descriptive statistics and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (N = 500).

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration of the CCCS model.

4.2.2. Gender Measurement Invariance

Primarily, the first-order model was specified distinctively for males and females. For the model considering male participants, goodness of fit indices showed an acceptable fit to the data: SBχ2 (101) = 196.274; p < 0.001; SBχ2/df = 1.93; CFI = 0.925; TLI = 0.911; RMSEA = 0.070, 90% C.I. [0.057 -0.079]; SRMR = 0.071. For the model considering female participants, the goodness of fit indices also revealed a good fit to the data: SBχ2 (101) = 236.386; p < 0.001; SBχ2/df = 2.34; CFI = 0.946; TLI = 0.936; RMSEA = 0.066, 90% C.I. [0.056 −0.076]; SRMR = 0.062.

In the second step, the measurement invariance of CCCS was assessed using the whole sample (Table 6). Regarding configural invariance, the model showed a good fit, SBχ2 (202) = 431.147; p < 0.001; SBχ2/df = 2.134; CFI = 0.939; TLI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.067, 90% C.I. [0.060, 0.075]; SRMR = 0.063. This indicated that the factor structure of the scale was equal between males and females. Subsequently, the metric invariance model was evaluated, and it showed a good model fit: SBχ2 (215) = 458.218; p < 0.001; SBχ2/df = 2.131; CFI = 0.936; TLI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.067, 90% C.I. [0.060, 0.074]; SRMR = 0.072. Although there was a statistically significant decrease in SB-DIFFTEST (=27.427, df = 13, p < 0.05), a non-significant decrease in |ΔCFI| = 0.003 and |ΔRMSEA| = 0.000, was found, suggesting that the items in the CCCS were consistently related to the latent factors, regardless of gender. Finally, the scalar invariance model was specified. This model showed good fit: SBχ2 (228) = 501.055; p < 0.001; SB χ2/df = 2.198; CFI = 0.928; TLI = 0.924; RMSEA = 0.069, 90% C.I. [0.062, 0.076]; SRMR = 0.075. Despite the statistically significant decrease in SB-DIFFTEST (=56.977, df = 13, p < 0.05), we found a non-significant decrease in |ΔCFI| = 0.008 and |ΔRMSEA| = 0.002, demonstrating that the expected item response was obtained at the same absolute level for both female and male samples.

Table 6.

Comparison of models for measurement invariance.

4.2.3. Reliability and Validity

Regarding reliability, for the Meaning-Centered Coping dimension (Factor 1), Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.828 and 0.827, respectively. For the Problem-Centered Coping dimension (Factor 2), Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.940 and 0.940, respectively. Finally, for the De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping dimension (Factor 3), Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.852 and 0.852, respectively.

According to Fornell and Larker’s [89] criteria for convergent validity, all factors’ loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and above the threshold of 0.50, as reported in Table 5 and in Figure 1. The Composite Reliability (CR) for the three dimensions was 0.830 (Factor 1), 0.940 (Factor 2), and 0.859 (Factor 3). As reported in Table 7, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for the three dimensions was 0.703 (Factor 1), 0.871 (Factor 2), and 0.708 (Factor 3). All AVE values exceeded the cut-off value of 0.50. The squared correlations between the three factors were lower than their respective AVE values, indicating the absence of multicollinearity and verifying the internal validity of the measure.

Table 7.

AVE values of CCCS dimensions.

Regarding the convergent and external validity of the CCCS, correlation analyses with several validated scales were conducted. The results of these analyses are presented in tabular form in the Supplementary Material (Table S1). Specifically, the findings showed a significant and positive association between Meaning-Centered Coping and Climate Change Worry (r = 0.12; p < 0.01), Global Pro-Environmental Behavior (r = 0.15; p < 0.01), Reduction of Waste (r = 0.17; p < 0.01), Vegetable Consumption (r = 0.12; p < 0.01), Waste Segregation (r = 0.10; p < 0.01), Pathways (r = 0.20; p < 0.01); Agency (r = 0.19; p < 0.01) and Positive Emotions regarding Climate Change (r = 0.30; p < 0.01). Concerning Problem-Centered Coping, the results showed a positive and significant association with Climate Change Worry (r = 0.55; p < 0.01), Global Pro-Environmental Behavior (r = 0.38; p < 0.01), Reduction of Waste (r = 0.48; p < 0.01), Vegetable Consumption (r = 0.29; p < 0.01), Environmental Activism (r = 0.18; p < 0.01), Sustainable Clothing (r = 0.30; p < 0.01), Waste Segregation (r = 0.15; p < 0.01), Pathways (r = 0.21; p < 0.01), Agency (r = 0.19; p < 0.01), Future Anxiety (r = 0.21; p < 0.01), Positive Emotions regarding Climate Change (r = 0.23; p < 0.01), and Negative Emotions regarding Climate Change (r = 0.39; p < 0.01). Furthermore, we found a negative and significant association between Problem-Centered Coping and Meat Consumption (r = −0.26; p < 0.01). Finally, De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping was negatively and significantly associated with Climate Change Worry (r = −0.23; p < 0.01), Reduction of Waste (r = −0.24; p < 0.01), Vegetable Consumption (r = −0.14; p < 0.01), Sustainable Clothing (r = −0.10; p < 0.01), Waste Segregation (r = −0.22; p < 0.01), Pathways (r = −0.10; p < 0.01), Future Anxiety (r = −0.20; p < 0.01), and Negative Emotions regarding Climate Change (r = −0.22; p < 0.01). Furthermore, positive and significant correlations between De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping, Meat Consumption (r = 0.25; p < 0.01) and Positive Emotions regarding Climate Change (r = 0.15; p < 0.01) were also found.

4.2.4. Group Differences

t-tests and ANOVA analyses examining sociodemographic differences in the three climate change coping strategies revealed several significant differences. Specifically, concerning gender, a t-test indicated significantly higher scores in Meaning-Centered Coping for males compared to females (MMale = 4.02 vs. MFemale = 3.80; t(498) = 1.93 p = 0.05; d = 0.18). Similarly, female participants exhibited significantly higher scores in Problem-Centered Coping compared to male ones (MFemale = 4.84; vs. MMale = 4.29; t(498) = 3.83; p < 0.001; d = 0.35). Additionally, results showed that young individuals who reported being members of or participating in environmental organizations had higher levels of Meaning-Centered Coping (MEnvAssYes = 4.92 vs. MEnvAssNo = 3.36; t(498) = 2.22; p < 0.05; d = 0.45) and lower levels of De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping (MEnvAssYes = 1.47 vs. MEnvAssNo = 1.95; t(498) = −3.25; p < 0.001; d = 0.63) compared to those who did not participate.

Regarding relationship status, t-test results showed significantly higher scores in Problem-Centered Coping for young adults in a relationship compared to those who were single (MRelationship = 4.85 vs. MSingle = 4.40; t(498) = 1.93; p < 0.001; d = 0.29).

As for occupational status, ANOVA revealed significant differences in Meaning-Centered Coping (F(3, 496) = 2.76; p < 0.05; η2 = 0.02) and Problem-Centered Coping (F(3, 496) = 3.18; p < 0.05; d = 0.02). Specifically, Tukey’s post hoc test indicated that students exhibited higher levels of Meaning-Centered Coping (MStudents = 4.00 vs. MWorkers = 3.57; p < 0.05) and Problem-Centered Coping (MStudents = 4.70 vs. MWorkers = 4.15; p < 0.05) compared to workers.

For political orientation, ANOVA revealed significant differences in Problem-Centered Coping (F(3, 496) = 17.79; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.10) and De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping (F(3, 496) = 15.93; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.09). Tukey’s post hoc test showed that individuals who identified as left-wing had higher levels of Problem-Centered Coping compared to those who identified as centrist (MLeft = 5.09 vs. MCentrist = 4.33; p < 0.01), politically disinterested (MLeft = 5.09 vs. MPoliticaldisint. = 4.09; p < 0.001), and right-wing (MLeft = 5.09 vs. MRight = 3.92; p < 0.01). Furthermore, individuals who identified as left-wing had lower levels of De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping compared to those who identified as right-wing (MLeft = 1.28 vs. MRight = 1.72; p < 0.05), centrist (MLeft = 1.28 vs. MCentrist = 1.77; p < 0.001) and politically disinterested (MLeft = 1.28 vs. MPoliticaldisint. = 1.77; p < 0.001).

5. General Discussion

The study outlines the process of the adaptation and validation of the Italian version of the CCCS, a tool designed to explore three different coping strategies for addressing climate change. The adaptation and validation of the CCCS aim to fill a gap in the existing literature, specifically the lack of an instrument to assess climate change-specific coping strategies within the Italian context. The CCCS was originally developed based on several qualitative studies [57,58,59], which identified three main coping categories related to climate change among youth and was initially tested with adolescents in a different cultural context [45,51]. In line with the recommendations of Boateng et al. [91], the adaptation and validation process followed several steps organized into two distinct but complementary studies, which ultimately led to the definitive version of the scale presented in Appendix A.

Study I aimed to explore the latent structure of the Italian version of the CCCS and evaluate its preliminary psychometric properties. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and optimized parallel analysis (PA) revealed a three-dimensional structure, namely Problem-Centered Coping (Factor 1), De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping (Factor 2), and Meaning-Focused Coping (Factor 3), consistent with the original version [45,51]. The EFA results confirmed the significant consistency of each item in defining the three-factor structure, with no issues of overlap [68]. Preliminary psychometric analyses demonstrated that all three factors exhibit a high likelihood of remaining stable across different studies, with good indices of factor accuracy and strong dimensional internal consistencies.

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), conducted in Study II on an independent sample of young adult Italians, confirmed the three correlated first-order factors structure identified in the previous study, with fit indices in line with the major recommendations in the literature [83,84]. All items loaded significantly and consistently onto the dimensions originally hypothesized [45,51], with all standardized coefficients being equal to or greater than 0.60 [88].

The gender invariance of the instrument was confirmed through several steps, which highlighted good fit indices for the model in both the male and female subgroups. Subsequently, the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models were tested, and alternative indices such as ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA were used to compare models, as they are less sensitive to sample size differences between the two groups compared to the chi-squared statistic [87,92]. The results of these analyses indicate that the CCCS is an appropriate method for measuring its various constructs for young adults of different genders (male vs. female), thus enabling comparisons of mean scores between the two subgroups and supporting multi-group SEM analyses.

The Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega indices suggest that all items play a significant role in defining the dimension to which they are associated, contributing to excellent internal dimensional consistency and high Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indices, key indicators of the good internal and convergent validity of the instrument [89]. The comparison of squared correlations between dimensions and their respective AVE values further confirmed the good discriminant validity and the absence of multicollinearity issues. Correlational analyses with other validated instruments further supported the convergent and external validity of the CCCS. Specifically, significant relationships were observed between Meaning-Centered Coping and EcoWorry, mirroring the recent findings by Pihkala [93]. At the same time, a significant association was found between this coping strategy and several pro-environmental behaviors, particularly Waste Reduction, Vegetable Consumption, and reduced Meat Consumption. These significant associations suggest that adopting Meaning-Centered Coping strategies could influence pro-environmental behaviors while preserving positive emotions and mental states that protect psychological well-being [55]. In our study, this coping style was also associated with Positive Emotions related to Climate Change, a sense of Agency, and the ability to plan goal achievement (Pathways). These results align with previous research highlighting the suitability of Meaning-Centered Coping in addressing climate change threats [35,50,51]. In addition, Problem-Centered Coping was strongly and positively associated with both EcoWorry and pro-environmental behavior, specifically Waste Reduction, Vegetable Consumption, Environmental Activism, Sustainable Clothing, and Recycling, and was negatively associated with Meat Consumption. These results confirm previous findings linking EcoWorry with Problem-Centered Coping [57,58,94,95]. Although the correlational results do not allow us to infer the direction of this relationship, they suggest a strong relationship—and potential impact—of this coping style on EcoWorry and climate distress, as explored elsewhere [47,49]. Moreover, the positive relationships between Problem-Centered Coping, sense of Agency, goal-achievement planning (Pathways), and pro-environmental behaviors are in line with Gifford [94], who argues that Problem-Centered Coping strategies are associated with greater agency and a sense of efficacy, which, in turn, leads to more sustainable lifestyles. Finally, De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping was negatively associated with EcoWorry, suggesting a potential protective function of this coping style on psychological well-being, due to the global and uncontrollable nature of the phenomenon [35,50,51]. At the same time, this coping strategy showed negative associations with Waste Reduction, Vegetable Consumption, Sustainable Clothing, and Recycling. These results, supported by a positive association with Meat Consumption, are consistent with previous findings indicating the detrimental impact of such strategies on sustainable actions [32,53,54]

Our findings also revealed higher levels of Meaning-Centered Coping in men and higher levels of Problem-Centered Coping in women. The latter seem to perceive climate change as a greater threat compared to men. Although this appears to reduce coping strategies focused on positive reappraisal, hope, and trust [33], it may also foster more active strategies to cope with the climate threat, which, in women, more easily translate into sustainable actions [13,96]. Furthermore, higher levels of Meaning-Centered Coping were found in young people who reported participating in environmental activities/organizations, who also showed lower levels of De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping. This result highlights how being part of a context that encourages sustainable action can reduce de-emphasizing or avoiding the problem while directing climate worry and anxiety toward sustainable actions, thus fostering hope and agency [97]. Among the participants, students showed significantly higher levels of both Meaning-Centered and Problem-Centered Coping compared to workers, who may face greater difficulties accessing educational resources and climate change awareness programs than students. The combination of educational and formative experiences could increase their awareness of the issue and, at the same time, facilitate behavioral engagement in activities aimed at changing environmental policies and promoting sustainability [98,99]. Similarly to students, those in a romantic relationship showed higher levels of Problem-Centered Coping compared to singles, which is in line with previous research highlighting the impact of climate change on couples’ future planning and decisions around having children. Perceiving the world as a dangerous place in which to raise children may prompt young couples to adopt Problem-Centered Coping more easily, seeking to change this perception through concrete, targeted, and tangible actions [28,100]. Finally, our results show how political ideology plays a significant role in the adoption of different coping strategies related to climate change. It emerged that young people with left-wing political ideology exhibited higher levels of Problem-Centered Coping and lower levels of De-Emphasizing/Avoidance Coping compared to those identifying with right-wing or centrist ideologies, or those who were generally indifferent to politics. In line with various contributions in the literature [101,102,103,104], these findings suggest that individuals with more conservative political ideologies tend to be less concerned and aware of the risks posed by climate change, more inclined to minimize or avoid the issue, and thus less likely to adopt active strategies for coping with it. In contrast, such strategies seem to prevail in groups with more liberal and progressive political ideologies.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. For instance, the use of convenience sampling and self-report measures introduces potential biases, particularly related to individual characteristics and social desirability, which may have influenced the results. To mitigate these limitations, future research could employ more representative sampling methods. Furthermore, most participants in this study were young adult students from Southern Italy. While this demographic was selected because of their heightened engagement with contemporary issues, as evidenced by the current findings, future studies could benefit from incorporating a more diverse sample of young adults, including a broader range of young workers, and considering variations in educational levels in greater detail. Since the instrument was validated with a group of Italian young adults, future research could evaluate and apply the tool to different target populations, such as adolescents or the general population. This would be valuable for exploring climate change coping strategies across different age groups and/or in various regions of Italy. Future studies might also examine the impact of environmental emotions on coping strategies in depth and consider dispositional variables that could influence the use of the different coping strategies assessed by the scale.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to expanding the range of valid and reliable instruments for exploring climate change in the Italian context, with a particular focus on coping strategies. The paper presents the adaptation and validation of the Climate Change Coping Scale (CCCS), an instrument that explores three coping strategies for dealing with climate change. The adaptation and validation process began with the exploration of the latent structure of the CCCS in the Italian context, which was subsequently confirmed by a good fit of the first-order factor structure. The instrument also demonstrated factor robustness, good internal consistency of the dimensions, invariance between male and female participants, and good discriminant and convergent validity. Overall, the results support using the CCCS to explore coping strategies related to climate change and address the growing need for robust, valid, and reliable psychometric tools to investigate this phenomenon in greater detail. The CCCS could be used to explore how Italian young adults are coping with climate change in terms of both informational and media exposure, as well as environmental emotions and sustainable actions. Indeed, coping strategies are important variables for both deepening the understanding of youth climate distress and exploring pro-environmental behavior. To conclude, investigating coping strategies for climate change could have significant practical implications in guiding the design and implementation of interventions aimed at supporting sustainable actions and mitigating climate distress, which is increasing among the Italian youth population [28,29,30]. Specifically, the CCCS could support the design of educational and awareness-raising interventions on climate crisis issues in schools, universities, and organizations, aimed at enhancing those coping strategies that are more functional both for the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors and for managing environmental emotions. The CCCS could serve as a tool to assess the effectiveness of interventions over time, aiming to increase the use of more effective coping strategies for the climate crisis, thereby supporting the well-being of the youth population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17062622/s1. Supplementary Material: Table S1 (Correlations between CCCS and other variables).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.M.R. and B.D.R.; Methodology: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Software: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Validation: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Formal Analysis: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Investigation: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Resources: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Data Curation: G.M.R. and G.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Writing—Review and Editing: G.M.R., G.T. and B.D.R.; Visualization: G.M.R. and G.T.; Supervision: B.D.R.; Project Administration: G.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the ethical guidelines established by the American Psychological Association for the treatment of human research participants and was in line with the principles outlined in the 1995 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, as well as the standards set forth in the Ethical Code of the Psychologist of the Italian National Council of the Order of Psychologists. All research described in the paper underwent review and received approval from the Psychological Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Humanities at the University of Naples Federico II (Approval Code: protocol number 1-2023; Approval Date: 13 January 2023; Scientific Project Manager: G.M.R.).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was acquired from all individuals participating in the study. The data gathered were analyzed solely in aggregated form, ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of participants, who were free to withdraw from the study at any point.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- The Italian Version of the Climate Change Coping Scale (CCCS)Giorgio Maria Regnoli, Gioia Tiano and Barbara De RosaQuando oggi si sente parlare di cambiamento climatico, ci si può sentire preoccupati o turbati. Di seguito trovi una serie di affermazioni, indica quanto ognuna di esse rispecchia il tuo pensiero o comportamento esprimendo il grado di accordo o disaccordo.[When discussing climate change today, one might feel worried or unsettled. Below are a series of statements; please indicate how each reflects your thoughts or behaviors by expressing your level of agreement or disagreement]Quando sento parlare del Cambiamento Climatico…[When I hear about Climate Change...]1. Ho fiducia nell’uomo e nell’umanità, possiamo risolvere la maggior parte dei problemi.[I have faith in humanity, we can fix all problems.]2. Confido che gli scienziati trovino una soluzione in futuro.[I trust scientists to come up with a solution in the future.]3. Ho fiducia nelle organizzazioni ambientaliste.[I have faith in people engaged in environmental organizations.]4. Confido che i politici approvino una legislazione che affronti la questione.[I trust politicians to pass legislation that addresses the issue.]5. Anche se il cambiamento climatico è un grosso problema, penso che si debba avere speranza.[I think, even though it is a big problem, one has to have hope.]6. Penso a cosa posso fare io stesso per affrontarlo.[I think about what I myself can do to address it.]7. Cerco informazioni su cosa posso fare per affrontarlo.[I search for information about what I can do to address it.]8. Parlo con la mia famiglia o i miei amici di cosa si può fare per aiutare.[I talk with my family and friends about what one can do to help.]9. Cerco di intraprendere azioni utili ad affrontare il problema piuttosto che evitarlo.[I try to take proactive actions to deal with the problem rather than avoiding it.]10. Reagisco alle mie preoccupazioni facendo cose che nella mia vita abbiano un impatto duraturo sugli altri.[I cope with my worries by doing things in my life that will have a lasting impact on others.]11. Penso che il cambiamento climatico sia una questione esagerata.[I think that climate change is exaggerated.]12. Non mi interessa visto che non so molto del cambiamento climatico.[I don’t care since I don’t know much about climate change.]13. Penso che il cambiamento climatico sia qualcosa di positivo visto che le estati saranno più calde.[I think climate change is something positive because the summers will get warmer.]14. Non mi interesso minimamente del cambiamento climatico.[I can’t be bothered to care about climate change.]15. Penso che il cambiamento climatico non riguardi noi che viviamo in Italia.[I think that climate change does not concern those of us living in Italy.]16. Penso che nulla di veramente grave accadrà nel corso della mia vita.[I think that nothing really serious will happen during my lifetime.]Response range for each item:1 = Pienamente in disaccordo; 2 = In disaccordo; 3 = Parzialmente in disaccordo; 4 = Né d’accordo né in disaccordo; 5 = Parzialmente d’accordo; 6 = D’accordo; 7 = Pienamente d’accordo.[1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Slightly disagree; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = Slightly agree; 6 = Agree; 7 = Strongly agree]Reverse Item: NoScoring:Coping centrato sul significato [Meaning Centered Coping] = Mean (item da 1–5);Coping centrato sul problema [Problem Centered Coping] = Mean (item da 6 a 10);Coping evitante/de-enfatizzante = [De-emphasizing/Avoidance Coping] = Mean (item da 11 a 16).

References

- IPPC—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021-Sixth Assessment Report; IPPC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When Climate Change Concern Leads to Climate Action: How Values, Concern, and Personal Responsibility Relate to Various Climate Actions. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adler, C.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Ibrahim, Z.Z. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Lottie, L.; Servet, Y. Is Set to Be the Hottest Year on Record: How Fast Are European Countries Heating Up? 2023. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2023/09/09/2023-is-set-to-be-the-hottest-year-on-record-how-fast-are-european-countries-heating-up (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Legambiente. Bilancio 2024: Italia Sotto Scacco Della Crisi Climatica; Legambiente: Rome, Italiy, 2024; Available online: https://www.legambiente.it/news-storie/clima/bilancio-2024-italia-sotto-scacco-della-crisi-climatica/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Patterson, C. Managing the Health Effects of Climate Change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnar, M.R.; Vazquez, D. Stress Neurobiology and Developmental Psychopathology. In Developmental Psychopathology: Developmental Neuroscience, 2nd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2007; pp. 533–577. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global Climate Change and Mental Health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vida, S.; Durocher, M.; Ouarda, T.B.; Gosselin, P. Relationship Between Ambient Temperature and Humidity and Visits to Mental Health Emergency Departments in Québec. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate Anxiety: Psychological Responses to Climate Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’-Syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrobe, S. Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, A.; Rossi, A.; Tessitore, F.; Troisi, G.; Mannarini, S. Mental health through the COVID-19 quarantine: A growth curve analysis on Italian young adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawrych, M. Climate change and mental health: A review of current literature. Psych. Pol. 2021, 56, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating environmental concern in the context of psychological adaption to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K.L.; Karasu, M. Climate Anxiety, Wellbeing and Pro-Environmental Action: Correlates of Negative Emotional Responses to Climate Change in 32 Countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; De Rosa, B.; Palombo, P. “Voice to the Youth”: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Pandemic Experience in Italian Young Adults. Medit. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1619–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; Sommantico, M.; De Rosa, B. Lockdown Young Adult Concerns Scale (LYACS): The Development and Validation Process. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; De Rosa, B. Italian Adaptation and Validation of the Fear of War Scale and the Impact of the Fear of War on Young Italian Adults’ Mental Health. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; De Rosa, B. How Is the Fear of War Impacting Italian Young Adults’ Mental Health? The Mediating Role of Future Anxiety and Intolerance of Uncertainty. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; De Rosa, B. Serial Mediation Models of Future Anxiety and Italian Young Adults Psychological Distress: The Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty and Non-Pathological Worry. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1834–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; De Rosa, B. Is Climate Change Worry Fostering Young Italian Adults’ Psychological Distress? An Italian Exploratory Study on the Mediation Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty and Future Anxiety. Climate 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Parola, A.; De Rosa, B. Development and Validation of the War Worry Scale (WWS) in a Sample of Italian Young Adults: An Instrument to Assess Worry About War in Non-War-Torn Environments. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.E.S.; Carmen, B.P.B.; Luminarias, M.E.P.; Mangulabnan, S.A.N.B.; Ogunbode, C.A. An Investigation into the Relationship Between Climate Change Anxiety and Mental Health Among Gen Z Filipinos. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 7448–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, K.; Gow, K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? Int. J. Clim. Change Strat. Manag. 2010, 2, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deloitte. Millennial e GenZ Vogliono Più Attenzione All’Ambiente, Work Life Balance e Flessibilità; Deloitte: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/it/it/pages/about-deloitte/articles/deloitte-global-2022-gen-z-and-millennial-survey---deloitte-italy---about.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Deloitte. Deloitte 2024 CxO Sustainability Report; Deloitte: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/climate/cxo-sustainability-report.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A. Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A.; Wagner, U. Coping with global environmental problems: Development and first validation of scales. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 754–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Stern, P.C.; Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S.; Reser, J.P.; Weber, E.U.; Gifford, R.; Howard, G.S. Psychology’s contributions to understanding and addressing global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E.A.; Edge, K.; Altman, J.; Sherwood, H. Searching for the Structure of Coping: A Review and Critique of Category Systems for Classifying Ways of Coping. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 216–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotions and Interpersonal Relationships: Toward a Person-Centered Conceptualization of Emotions and Coping. J. Pers. 2006, 74, 9–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A.; McIntosh, D.N.; Poulin, M.; Gil-Rivas, V. Nationwide Longitudinal Study of Psychological Responses to September 11. JAMA 2002, 288, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.A. Emotion Regulation and Mental Health: A Review of Experimental Research. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 71, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, D.A.; Smith, L.A.; Jones, R.B. Coping Strategies and Mental Health in Adolescence. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Stress Health 2008, 24, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H. The Role of Coping in Understanding the Mental Health Consequences of Stress. In Handbook of Stress, Coping, and Health: Implications for Nursing Research, Theory, and Practice; Wadsworth, W.W., Sterm, M.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Situational Coping and Dispositional Coping Dispositions in a Stressful Transaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and Promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci Bitti, P.E.; Gremigni, P. Psicologia Della Salute; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.; Macpherson, M.J.; Meador, M.; Petri, H. How West German adolescents experience the nuclear threat. Polit. Psychol. 1989, 10, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.T. Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: A meta analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallis, D.; Slone, M. Coping strategies and locus of control as mediating variables in the relation between exposure to political life events and psychological adjustment in Israeli children. Int. J. Stress Manag. 1999, 6, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, J.C.; Brennan, M.; Colarossi, L. Event-exposure stress, coping, and psychological distress among New York students at six months after 9/11. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional Assessment of Coping: A Critical Evaluation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Coping with Climate Change Among Adolescents: Implications for Subjective Well-being and Environmental Engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleeman, S.; O’Riordan, T.; Jaeger, C.C. The psychology of denial concerning climate change mitigation measures: Evidence from Swiss focus groups. Glob. Environ. Change 2001, 11, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Spears, R.; Leach, C.W. Experimental evidence for a dual pathway model analysis of coping with the climate crises. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Folkman, S. Meaning in the Context of Stress and Coping. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S. Coping with Climate Change: The Role of Psychological Resilience. In Psychology and the Environment: An Introduction; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Confronting Macrosocial Worries: Worry About Environmental Problems and Proactive Coping Among a Group of Young Volunteers. Futures 2007, 39, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and Worry: Exploring Young People’s Values, Emotions, and Behavior Regarding Global Environmental Problems. Doctoral Dissertation, Örebro Studies in Psychology 11, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Recycling and Ambivalence: Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Household Recycling Among Young Adults. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Climate Change, Coping Strategies, and Emotions: A Review of Research on the Emotional Dimensions of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ytre-Arne, B.; Moe, H.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K. Investigating Associations Between Media Exposure, Climate Anxiety and Mental Health (MECAMH). 2019. Available online: https://osf.io/6n4rb/?view_only=d708efc61e6945a1bc02e037a3ccac96 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Syropoulos, S.; Law, K.F.; Mah, A.; Young, L. Intergenerational Concern Relates to Constructive Coping and Emotional Reactions to Climate Change via Increased Legacy Concerns and Environmental Cognitive Alternatives. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Tian, L.K. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; de Vet, H.C. Quality Criteria Were Proposed for Measurement Properties of Health Status Questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Knekta, E.; Runyon, C.; Eddy, S. One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Using Factor Analysis to Gather Validity Evidence When Using Surveys in Your Research. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2019, 18, rm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. MSA: The Forgotten Index for Identifying Inappropriate Items Before Computing Exploratory Item Factor Analysis. Methodology 2021, 17, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, M.E.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Dimensionality Assessment of Ordered Polytomous Items with Parallel Analysis. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-29 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Factor Analysis Program. 2023. Available online: https://psico.fcep.urv.cat/utilitats/factor/Download.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample Size in Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.E. Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Faggi, V.; Ciabini, L.; Castellini, G.; Galassi, F.; Ricca, V. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Climate Change Worry Scale. J. Clim. Change Health 2022, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, C.; Capasso, M.; Pasquariello, R.; Caso, D.; Donizzetti, A.R. Validation of the Integrated Pro-Environmental Behaviours Scale (I_PEBS). Sustainability 2025. in review. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A.; Irving, L.M.; Sigmon, S.T.; Yoshinobu, L.; Gibb, J.; Langelle, C.; Harney, P. The Will and the Ways: Development and Validation of an Individual Differences Measure of Hope. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, S.; Quartiroli, A.; Baumann, D. Adaptation of the Snyder’s dispositional Hope Scale for Italian adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 5662–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannini, T.B.; Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Di Lorenzo, G. Validation of the Dark Future Scale (DFS) for future anxiety on an Italian sample. J. Psych. 2022, 2, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terraciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; Costa Jr, P.T. Factorial and Construct Validity of the Italian Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K.V. Measures of Multivariate Skewness and Kurtosis with Applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; BMDP Statistical Software: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]