Unveiling the Motivations Behind Cultivating Fungus-Resistant Wine Varieties: Insights from Wine Growers in South Tyrol, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

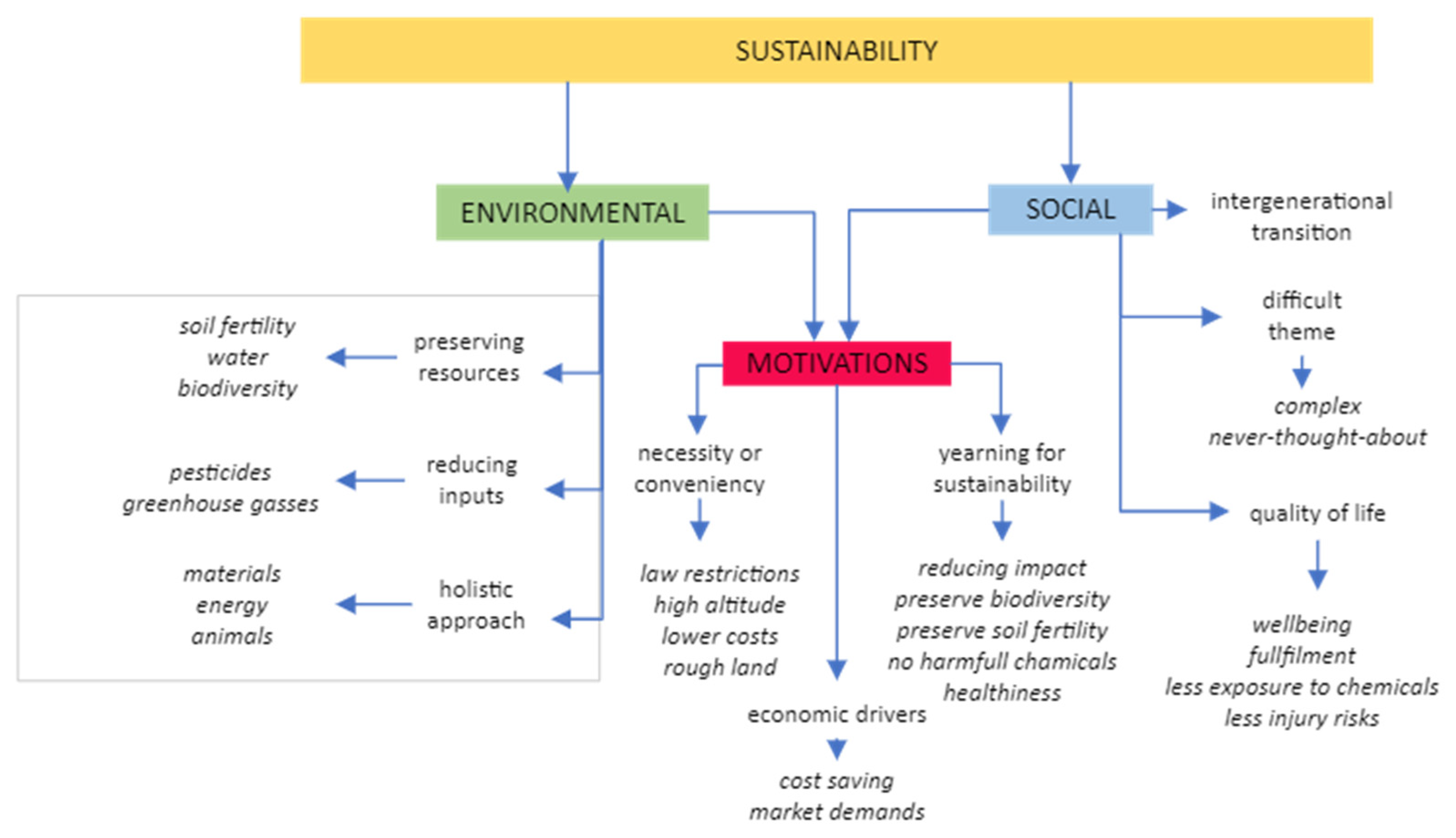

2. Conceptualizing Environmental and Social Sustainability in Agriculture

2.1. Fungus-Resistant Varieties, Organic and Biodynamic Wines: Different Steps Towards More Sustainable Agriculture

2.2. Ideological and Values-Based Assumptions in the Choices of Winegrowers

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Understanding of Sustainability for PIWI Producers in South Tyrol

“We also work biodynamically and there it is a question for us not only how to keep the land fertile, but also how to make it more fertile, for future generations. And there also the tractor rides don’t, if you only do 8 passes with the tractor on the soil or if you do 25 that also makes a difference [...] we don’t want to consume what we already have, you know, air, soil fertility, bridges, materials. For us sustainability is respect for the environment and for other people, but above all, as I said before, trying to carry on what we have for the future”.(I20)

“It is a matter of epistemology, that is, how you observe reality. So taking care of yourself is the first key ... it is the only key to, let’s say, increasing or having environmental sensitivity. Why? Because we are used to having or thinking about a boundary. I mean, between us and the environment. I mean, physics says that even if we see 3 to 50, at 700 nanometres physically the boundary is not there between me and what is outside. This means that if I see myself as part of the environment, and if I feel emotionally part of the environment, I should care about the environment. So sustainability means breaking this vision where I`m outside the environment and not part of it”.(I7)

“[Sustainability] is first and foremost about keeping our soil healthy, because every chemical ends up in the soil. Keeping the water table healthy, and that is perhaps the most important thing even. Keeping the air healthy as well. [...With PIWI wines] we talk about the 50% reduction of possible applications. We are also talking about a certain CO2 footprint”.(I17)

“Viticulture is highly dependent on crop protection products in the form of chemical or biological agents (fungicides). Without the regular use of these ’repellents’, high quality wine production would not be possible. This applies to both conventional and organic viticulture. PIWI are the true heroes among vines. They do not need these constant fungicides because they are natural robust against fungal diseases we are. They are sustainable and environmentally friendly because they require very few ecological crop protection agents and crop care products to produce excellent wines with an exciting variety of flavours. This directly protects the environment because few pesticides enter nature.”.(PIWI Südtirol website)

“The planting is 10 years old and we have not done any treatment on either the vines or the soil”.(Q12)

“For me, if the worker does his job well, and in the morning when we start he is punctual and laughs then it means that he likes what is going on during the day. And we try to make the work comfortable”.(I20)

“Applying a very simple concept, ethics in daily work, respect for people, involving them in decisions, training them and giving them the chance to develop”.(Q9)

“Many small producers who have another job, it’s like that here in general, who have little land, maybe taken from dad or granddad, there logically for them it would be a big advantage if they can plant PIWI, because there is less work, then those people have to do it on their days off no, if they have another fixed job”.(I20)

“Also the fact that you don’t have to risk it, we are in the hills so there is always a risk of tipping over, it is really job security. So yes, [the cultivation of resistant vines] does influence in a very positive way”.(I7)

4.2. A Light on the Motivations to Plant Resistant Varieties

“[I realised that] we always needed more treatments, bigger ones, or even new products to combat these infections, especially fungal ones, because to have a good product you have to have healthy leaves and healthy bunches. And it also became a great economic effort, because the chemical industry clearly takes advantage of the great need for these products and always evolves new ones to replace the others, but I bet they will always be more expensive. Otherwise, the discourse of the genuineness of products was also born; fifty years ago no one asked a big question about the genuineness of the elementary sector as far as products are concerned, but as the number of products also became more varied, this discourse was emerging. And it is only right that this discourse was born. Then the whole thing brought me more interest”.(I17)

“However, I have to say the truth that there is no market, …it is a market that needs to be developed. According to what I see, as an oenologist and also as a trader of this wine, I have to say that it is difficult....”.(I16)

“Another part [of the vineyard planted with PIWI] is, let’s say, quite steep hillsides and it’s about treatments, i.e., if you have to do five, four, one, two treatments, it’s already better than doing ten or more. The reasoning is just that: you have less work, the quality is fairly good, and also the philosophy of the farm is to go organic and to make as little impact as possible on its surroundings. So you say ’why not?’”.(I16)

“When we took over the farm, we said ’around the farm—because we also have a farmhouse—when we have guests on the pool we don’t want to spend every week with the sprayer’. That’s how the idea came about. And we got on well from the first moment, or rather, our first wine we made was good so we decided to go ahead and plant other quantities and other varieties”.(I20)

“part of the vineyard is right next to the house, they made the choice to make two rows next to the house because they did not want to treat their lawn, garden and house”.(I16)

“Dad was already very active in the 1980s in a group that I don’t know what it’s called in Italian: Umweltschutzgruppe [...] He never liked this farming he was doing, in the sense, he liked nature, agriculture in general but to use these poisons as they used in the ’60s-’70s, until the 80s, it was done like this because nothing else was known; but he confronted a lot [...] And then already in the ’80s he stopped using herbicides, then also mineral salts until he said ’yes, the only sustainable way is to work organically”.(I24)

“My father didn’t know what bio is. [... after the war] there was little to eat, there was little money. And that’s when fertiliser came, everything grew, no, but then with fertiliser also comes disease, because if it grows more, the disease has more room to develop. But that’s also when the chemical pesticides came, and then there was no problem. And my father says ’eh now we have found a method that brought Wellbeing [...] Now you don’t want to have any risks, to lose all [the crop]”.(I17)

“But I explained that I don’t want [chemicals], because maybe after 20 or 50 years you can’t produce any more, no you don’t know at that time what will happen. When I started I thought ’if we continue like this, like our parents did, maybe the land is dead’. And I told my father that if I can live off the farm I received, at that time when I had already started to do organic, if I can live I’ll do organic, if not, I’ll go back to conventional. Because my grandfather was able to live here on the farm with seven children, my father too, and I said ’I have to live here too’. And the luck was that I also had apples. We sold the apples to Germany and they asked for organic ones.”.(I27)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boix-Fayos, C.; de Vente, J. Challenges and potential pathways towards sustainable agriculture within the European Green Deal. Agric. Syst. 2023, 207, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal, COM 2019, 640 final, 11 December 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Sidhoum, A.A. Valuing social sustainability in agriculture: An approach based on social outputs’ shadow prices. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janker, J. Moral conflicts, premises and the social dimension of agricultural sustainability. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janker, J.; Mann, S. Understanding the social dimension of sustainability in agriculture: A critical review of sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 22, 1671–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, E.; García-Herrero, L.; Hall, D.; Segrè, A.; Vittuari, M. Social sustainability tools and indicators for the food supply chain: A systematic literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Y. Sustainable agriculture: Theories, methods, practices and policies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Vastola, A. Sustainable winegrowing. Current perspectives. Int. J. Wine Res. 2015, 7, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergamini, D.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G. Wine after the pandemic? All the doubts in a glass. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2021, 10, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, K.; Szolnoki, G.; Pabst, E. Motivation factors for organic wines. An analysis from the perspective of German producers and retailers. Wine Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, L.; Kimberly, N. German Winegrowers’ Motives and Barriers to Convert to Organic Farming. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, O.T.; Arcuri, S.; Cavicchi, A.; Galli, F.; Brunori, G.; Vergamini, D. Can alternative wine networks foster sustainable business model innovation and value creation? The case of organic and biodynamic wine in Tuscany. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1241062. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselhauf, L.; Fleuchaus, R.; Theuvsen, L. What about the environment? A choice-based conjoint study about wine from fungus-resistant grape varieties. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 32.1, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.altoadigewines.com/en/winegrowers/wine-producers/10-0.html (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Martín-García, B.; Longo, E.; Ceci, A.T.; Pii, Y.; Romero-González, R.; Garrido Frenich, A.; Boselli, E. Pesticides and winemaking: A comprehensive review of conventional and emerging approaches. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duley, G.; Ceci, A.T.; Longo, E.; Boselli, E. Oenological potential of wines produced from disease-resistant grape cultivars. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2591–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampridi, M.G.; Sørensen, C.G.; Bochtis, D. Agricultural sustainability: A review of concepts and methods. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velten, S.; Leventon, J.; Jager, N.; Newig, J. What is sustainable agriculture? A systematic review. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7833–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Chami, D.; Daccache, A.; El Moujabber, M. How can sustainable agriculture increase climate resilience? A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, J.R. Understanding how farm—Ers choose between organic and conventional pro- duction: Results from New Zealand and policy implications. Agric. Hum. Values 1999, 16, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Schneeberger, W.; Freyer, B. Converting or not converting to organic farming in Austria:Farmer types and their rationale. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Stanbury, P.; Dietrich, T.; Döring, J.; Ewert, J.; Foerster, C.; Freund, M.; Friedel, M.; Kammann, C.; Koch, M.; et al. Developing a sustainability vision for the global wine industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Binder, C.R. Towards an improved understanding of farmers’ behaviour: The integrative agent-centred (IAC) framework. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2323–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, L.M.; De Bernardi, V.; Sydow, A. Intra-family succession motivating eco-innovation: A study of family firms in the German and Italian wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janker, J.; Mann, S.; Rist, S. Social sustainability in agriculture: A system-based framework. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A.; Jerram, C.; Santiago-Brown, I.; Collins, C. Sustainability Assessment in Wine-Grape Growing in the New World: Economic, Environmental, and Social Indicators for Agricultural Businesses. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8178–8204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jung, H. Dynamic semantic network analysis for identifying the concept and scope of social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1510–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.; Legun, K.; Campbell, H.; Carolan, M. Social sustainability indicators as performance. Geoforum 2019, 103, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachev, H. Governance Sustainability of Bulgarian Agriculture at Ecosystem Level. South Asian Res. J. Agric. Fish. 2021, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlan, A. Social sustainability in agriculture: An anthropological perspective on child labour in cocoa production in Ghana. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasova-Chopeva, M. Evaluation of social sustainability of Bulgarian agriculture. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 25, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Nicli, S.; Elsen, S.U.; Bernhard, A. Eco-social agriculture for social transformation and environmental sustainability: A case study of the UPAS-project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Meredith, D.; Bonnin, C. ‘You have to keep it going’: Relational values and social sustainability in upland agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 2022, 63, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, K.S.; Bell, M.G.; Chirisa, I.; Duvall, C.S.; Egerer, M.; Hung, P.Y.; Yacamán Ochoa, C. Grand challenges in urban agriculture: Ecological and social approaches to transformative sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 668561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calker, K.J.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Giesen, G.W.J.; Huirne, R.B.M. Modelling worker physical health and societal sustainability at farm level: An application to conventional and organic dairy farming. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uleri, F.; Elsen, S. Ruralità tra risignificazione e centralità nuova: Giovani agricoltori e transizione alla multifunzionalità nelle valli Trentine e Altoatesine. Sociol. Urbana E Rural. 2023, 45, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medland, L. Working for social sustainability: Insights from a Spanish organic production enclave. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero-Gerbeau, Y.; López-Sala, A.; Șerban, M. On the social sustainability of industrial agriculture dependent on migrant workers. Romanian workers in Spain’s seasonal agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadra, F.; Viganò, F.; Elsen, S.U. Azioni di rete per la qualità sociale del lavoro agricolo e la prevenzione dello sfruttamento. In Agricoltura Sociale: Processi, Pratiche e Riflessioni per L’innovazione Sociosanitaria; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Roma, Italy, 2022; pp. 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Reigada, A.; Delgado, M.; Perez Neira, D.; Soler Montiel, M. The social sustainability of intensive agriculture in Almería (Spain): A view from the social organization of labour. Rev. Estud. Sobre Despoblación Y Desarro. Rural. 2017, 23, 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Prause, L. Digital agriculture and labor: A few challenges for social sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stattman, S.L.; Mol, A.P. Social sustainability of Brazilian biodiesel: The role of agricultural cooperatives. Geoforum 2014, 54, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathorne-Hardy, A.; Reddy, D.N.; Venkatanarayana, M.; Harriss-White, B. System of Rice Intensification provides environmental and economic gains but at the expense of social sustainability—A pmultidisciplinary analysis in India. Agric. Syst. 2016, 143, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgeram, R. “The only thing that isn’t sustainable... is the farmer”: Social sustainability and the politics of class among Pacific Northwest farmers engaged in sustainable farming. Rural Sociol. 2011, 76, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B. The social goals of agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 1986, 3, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.; Barling, D. ‘The right thing to do’: Ethical motives in the interpretation of social sustainability in the UK’s conventional food supply. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R.; Mariani, A. Wineries’ perception of sustainability costs and benefits: An exploratory study in California. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16164–16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; D’Amico, S.; Fouilleux, E. A relational perspective on the dynamics of the organic sector in Austria, Italy, and France. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Länn, A.; Wikholm, P. To Be, or Not to Be, Organic: Motives and Barriers for Swedish Wine Farmers to Use Organic Practices. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thiollet-Scholtus, M.; Muller, A.; Abidon, C.; Grignion, J.; Keichinger, O.; Koller, R.; Wohlfahrt, J. Multidimensional assessment demonstrates sustainability of new low-input viticulture systems in north-eastern France. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 123, 126210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletto, L.; Barisan, L.; Boatto, V.; AC Costantini, E.; Lorenzetti, R.; Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. More crop for drop–climate change and wine: An economic evaluation of a new drought-resistant rootstock. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2014, 6, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, P.; Pfenninger, H. Disease-resistant cultivars as a solution for organic viticulture. In Proceedings of the VIII International Conference on Grape Genetics and Breeding, Kecskemet, Hungary, 26–31 August 2002; Volume 603, pp. 681–685. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, R.; Pomarici, E.; Giampietri, E.; Borrello, M. Consumer acceptance of fungus-resistant grape wines: Evidence from Italy, the UK, and the USA. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrello, M.; Cembalo, L.; Vecchio, R. Consumers’ acceptance of fungus resistant grapes: Future scenarios in sustainable winemaking. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Will sustainability shape the future wine market? Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, D. Hybrid wine grapes and emerging wine tourism regions. In Routledge Handbook of Wine Tourism Saurabh; Kumar, D., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 603–613. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, K.; Legrand, W.; Sloan, P. The integration of fungus tolerant vine cultivars in the organic wine industry: The case of German wine producers. Enometrica Rev. Vineyard Data Quantif. Soc. Eur. Assoc. Wine Econ. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zagata, L. How organic farmers view their own practice: Results from the Czech Republic. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, N.; Orenstein, D.E. A transdisciplinary study of agroecological niches: Understanding sustainability transitions in vineyards. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, A.; Fragoso, R.; Marta-Costa, A. Sustainability awareness in the Portuguese wine industry: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2022, 20, 1437–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkoh, S.; Mensah, J. Application of triangulation in qualitative research. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 10, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A. Can organic farmers be ‘good farmers’? Adding the ‘taste of necessity’ to the conventionalization debate. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grando, S.; Bartolini, F.; Bonjean, I.; Brunori, G.; Mathijs, E.; Prosperi, P.; Vergamini, D. Small farms’ behaviour: Conditions, strategies and performances. In Innovation for Sustainability: Small Farmers Facing New Challenges in the Evolving Food Systems; Brunori, G., Grando, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2020; pp. 125–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lamine, C.; Garçon, L.; Brunori, G. Territorial agrifood systems: A Franco-Italian contribution to the debates over alternative food networks in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, L.; Luzzani, G.; Criscione, P.; Barro, L.; Bagnoli, C.; Capri, E. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Wine Industry: The Case Study of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, E.; Coelho, A.; Zadmehran, S. A comprehensive economic examination and prospects on innovation in new grapevine varieties dealing with global warming and fungal diseases. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmor, D.A. Behavioural studies in agriculture: Goals, values and enterprise choice. Ir. J. Agric. Econ. Rural. Sociol. 1986, 11, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, R.J. Seeing through the ‘good farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘productivist’ behavior. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. A farmer centric approach to decision making and behaviour change: Unpacking the “black-box” of decision making theories in agriculture. In Proceedings of the Future of Sociology, the Australian Sociological Association 2009 Annual Conference, Canberra, Australia, 1–4 December 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Number | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Documental analysis (Website) | 27 | January–March 2023 |

| In-depth interviews | 7 | March–April 2023 |

| Online survey | 6 | May–June 2023 |

| Participant observation | 2 | September 2023 |

| Interview with the director of the Südtirol Association | 1 | April 2023 |

| ID | Data Collection Method | Organic Certified | Only PIWI | Other Labels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Survey + website | Yes | No | Bioland 1 + Vegan 2 + ‘Vignaioli indipendenti’ 3 + Demeter 4 |

| 2 | Website | No | No | |

| 3 | Survey + website | No | Yes | |

| 4 | Survey + website | Yes | Yes | Bioland + Vignaioli indipendenti |

| 5 | Website | Yes | No | Bioland + Vignaioli indipendenti |

| 6 | Website | No | No | |

| 7 | Interview + web | Yes | No | Bioland + Vignaioli indipendenti |

| 8 | Website | No | No | |

| 9 | Survey + website | Yes | No | Natural wine 5 |

| 10 | Website | Yes | No | Bioland |

| 11 | Website | No | No | |

| 12 | Survey+ website | No | No | |

| 13 | Website | Yes | No | Tyrolensis ars vini 6 |

| 14 | Website | Yes | No | |

| 15 | Website | No | No | |

| 16 | Interview + web | No | No | |

| 17 | Interview + web | Yes | No | |

| 18 | Interview + web | Yes | No | Bioland + Vignaioli indipendenti |

| 19 | Website | No | No | |

| 20 | Interview + web | Yes | No | Demeter |

| 21 | Website | Yes | No | Bioland + vignaioli indipendenti |

| 22 | Website | Yes | Yes | Natural wine |

| 23 | Website | Yes | No | Bioland |

| 24 | Interview + web | Yes | No | Natural wine + bioland |

| 25 | Website | No | Yes | |

| 26 | Survey+ website | Yes | Yes | BioWeis (Bio-Wein-Valle d’Isarco) 7 |

| 27 | Interview + web | Yes | No | Demeter |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piccoli, A.; Viganò, F. Unveiling the Motivations Behind Cultivating Fungus-Resistant Wine Varieties: Insights from Wine Growers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062615

Piccoli A, Viganò F. Unveiling the Motivations Behind Cultivating Fungus-Resistant Wine Varieties: Insights from Wine Growers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062615

Chicago/Turabian StylePiccoli, Alessandra, and Federica Viganò. 2025. "Unveiling the Motivations Behind Cultivating Fungus-Resistant Wine Varieties: Insights from Wine Growers in South Tyrol, Italy" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062615

APA StylePiccoli, A., & Viganò, F. (2025). Unveiling the Motivations Behind Cultivating Fungus-Resistant Wine Varieties: Insights from Wine Growers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability, 17(6), 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062615