Building Business Resilience Through Strategic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Culinary Micro-Enterprises in Bandung During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

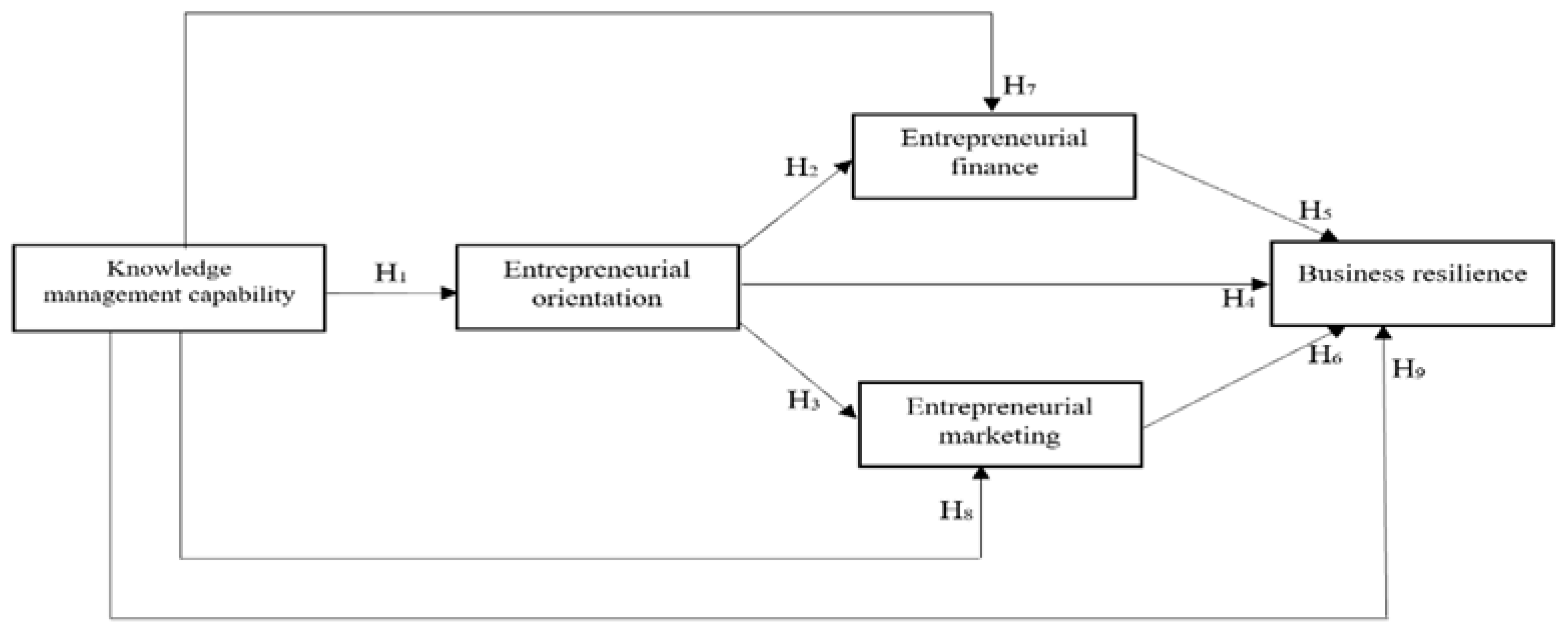

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. Knowledge Management Capability (KMC) as an Independent Variable

2.2. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) and Entrepreneurial Finance (EF)

2.3. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) and Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM)

2.4. Business Resilience (BR) as a Dependent Variable

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

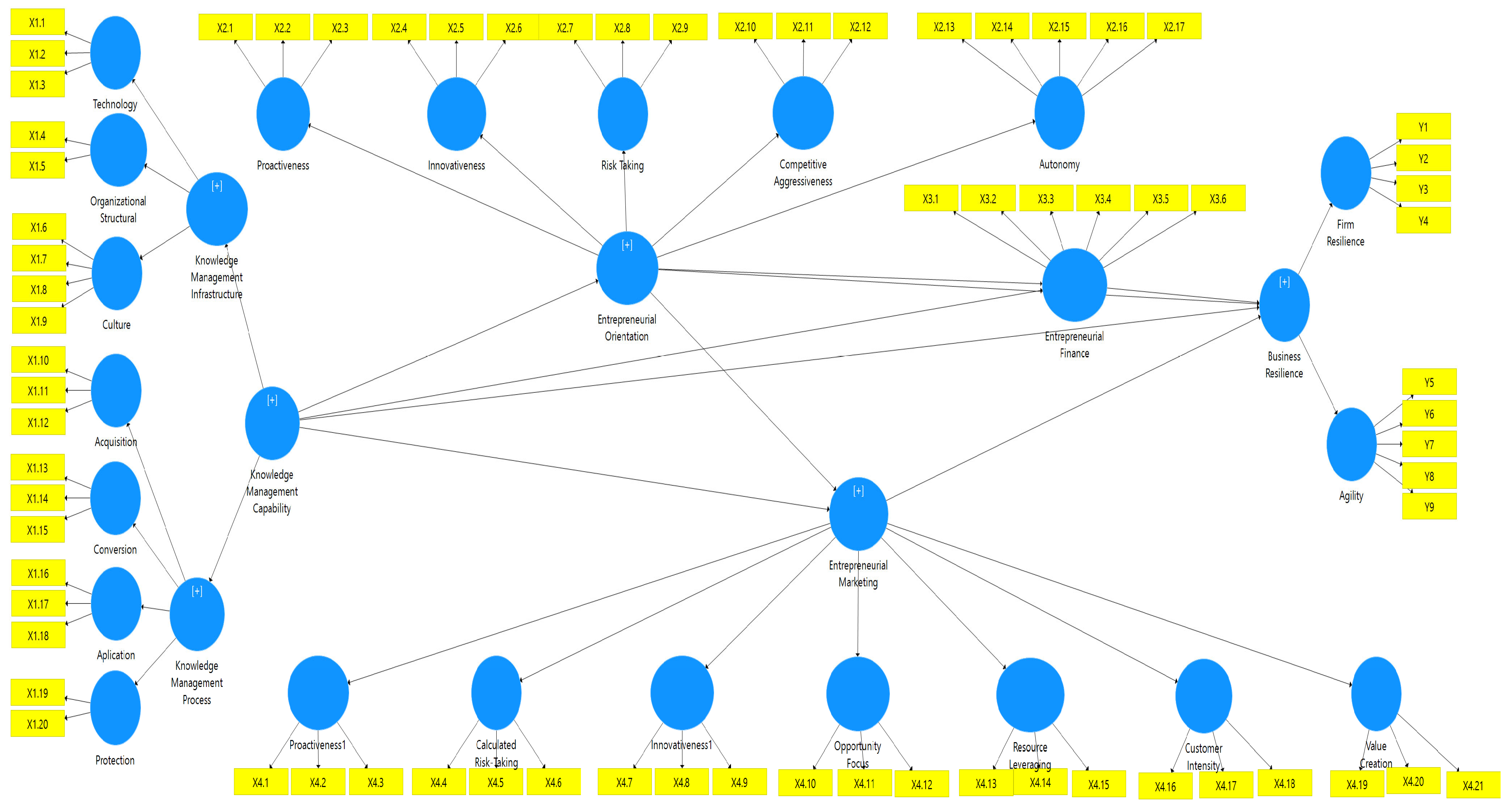

3.2. Variables and Indicators

3.3. Analytical Technique

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

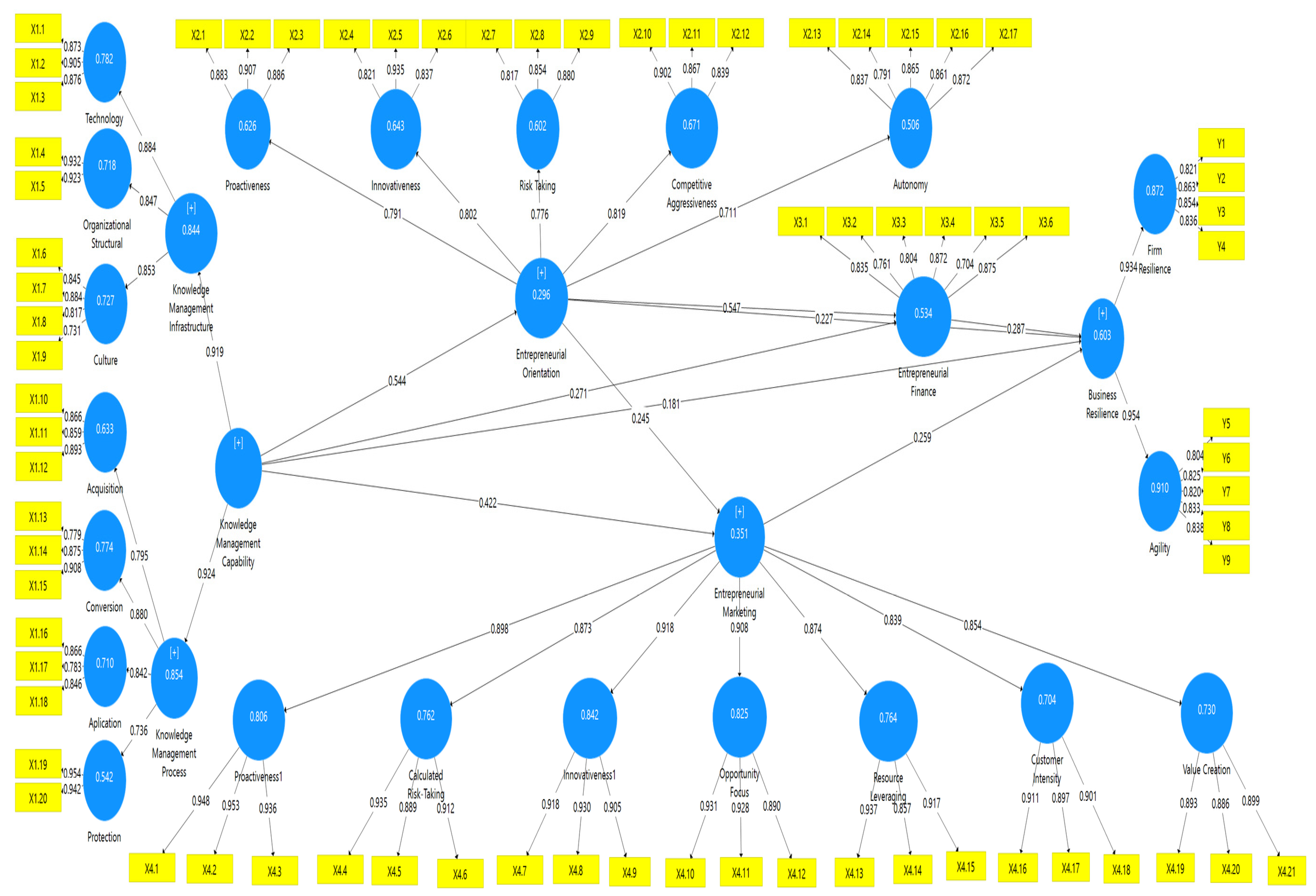

4.2. Outer Model Results

4.3. Inner Model Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoritical and Policy Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breier, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Clauss, T.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S.; Tiberius, V. The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 Crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, S.; Branicki, L.; Linnenluecke, M.K. COVID-19, societalization, and the future of business in society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on Business and Research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Dasí-Rodríguez, S. The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damilola, O.; Deborah, I.; Oyedele, O.; Kehinde, A.-A. Global pandemic and business performance. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, W.; Fernando, R. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenario. Asian Econ. Pap. 2020, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E.W.; Muldoon, J.; Ogundana, O.M.; Lee, Y.; Wilson, G.A. Charting the future of entrepreneurship: A roadmap for interdisciplinary research and societal impact. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2314218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Bejinaru, R. COVID-19 induced emergent knowledge strategies. Knowl. Process Manag. 2021, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, R.V.; Llanos-Contreras, O.; Hebles, M. Post-disaster recovery for family firms: The role of owner motivations, firm resources, and dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Kraus, S.; Vrontis, D. Assessing the AI-CRM technology capability for sustaining family businesses in times of crisis: The moderating role of strategic intent. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2023, 13, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikanova, R.M.; Cvik, E.D.; MacGregor, R.K. Addressing the COVID-19 challenges by SMEs in the hotel industry—A czech sustainability message for emerging economies. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, R. How Can Resilience Create and Build Market Value? J. Creat. Value 2022, 8, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floetgen, R.J.; Strauss, J.; Weking, J.; Hein, A.; Urmetzer, F.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Introducing platform ecosystem resilience: Leveraging mobility platforms and their ecosystems for the new normal during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrings, C. Resilience and sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, M. Economic crisis and resilience: Resilient capacity and competitiveness of the enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1924–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Sirmon, D.G.; Trahms, C.A. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating Value for Individuals, Organizations, and Society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Covin, J.G.; Kuratko, D.F. Conceptualizing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Kuratko, D.F.; Schindehutte, M. Towards integration: Understanding entrepreneurship through frameworks. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2001, 2, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A. International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 925–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (covid-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baporikar, N. Handbook of Research on Sustaining SMEs and Entrepreneurial Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A. Multilevel entrepreneurship research: Opportunities for studying entrepreneurial decision making. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.T.; Kor, Y.Y. The Entrepreneurial Mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportunity in an Age of Uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.D.; Heppard, K.A. Entrepreneurship as Strategy: Competing on the Entrepreneurial Edge; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Camp, S.M.; Sexton, D.L. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Integrating Entrepreneurial and Strategic Management Perspectives. Strateg. Entrep. Creat. A New Mindset 2017, 1, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, B. Strategic entrepreneurship. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.T.N.; Neck, P.A.; Nguyen, T.H. The Critical Role of Knowledge Management in Achieving and Sustaining Organisational Competitive Advantage. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 2, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Karreman, D. Odd couple: Making sense of the curious concept of knowledge management. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 995–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeen, J.D.; Zack, M.H.; Singh, S. Knowledge management and organizational performance: An exploratory survey. Proc. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst. Sci. 2006, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R. Knowledge management and the conduct of expert labour. In Managing Knowledge: Critical Investigations of Work and Learning; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan, P.; Jafari, M.; Fathian, M. Critical success factors of knowledge management systems: A multi-case analysis. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2006, 18, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Davenport, T.H. General perspectives on knowledge management: Fostering a research agenda. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Wright, L.T. Defining the Scope of Entrepreneurial Marketing: A Qualitative Approach. J. Enterprising Cult. 2000, 8, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabeche, Z.; Soudani, A.; Brahmi, M.; Aldieri, L.; Vinci, C.P.; Abdelli, M.E.A. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Organizational Culture and Business Performance in SMEs: Evidence from Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Envick, B.R. Gender and entrepreneurial orientation: A multi-country study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 9, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Turro, A.; Wright, M.; Zahra, S. Corporate entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 1541–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C.A.; Kanyangale, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and survival of small and medium enterprises in Nigeria: An examination of the integrative entrepreneurial marketing model. Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N.M.N.; Mahmood, R. Mediating role of competitive advantage on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of small and medium enterprises. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 2444–2452. Available online: https://www.makhillpublications.co/files/published-files/mak-ibm/2016/12-2444-2452.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Gergely, F. The effects of strategic orientations and perceived environment on firm performance. J. Compet. 2016, 8, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, J. Debt policy and performance of SMEs: Evidence from Ghanaian and South African firms. J. Risk Financ. 2007, 8, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavitis, C.; Filatotchev, I.; Kamuriwo, D.S.; Vanacker, T. Entrepreneurial finance: New frontiers of research and practice: Editorial for the special issue Embracing entrepreneurial funding innovations. Ventur. Cap. 2017, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; LaForge, R.W. Entrepreneurial Marketing: A Construct for Integrating Emerging Entrepreneurship and Marketing Perspectives. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, G.E.; Hultman, C.M.; Miles, M.P. The Evolution and Development of EM. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Harms, R.; Fink, M. Entrepreneurial marketing: Moving beyond marketing in new ventures. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2010, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Rowley, J. Presentation of a generic ‘EMICO’ framework for research exploration of entrepreneurial marketing in SMEs. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2009, 11, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock-Doepgen, M.; Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Cheng, C.F. Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N.; Yuli, Z.; Hongzhi, X. Acquisition of resources, formal organization and entrepreneurial orientation of new ventures. J. Chin. Entrep. 2008, 1, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, C.; De Toni, A.F.; Pillon, R. Inter-organisational technology/knowledge transfer: A framework from critical literature review. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 1195–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Morgan, R.E. Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galunic, D.C.; Rodan, S. Resource recombinations in the firm: Knowledge structures and the potential for schumpeterian innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S. Knowledge management processes in SMES and large firms: A comparative evaluation. African J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oliver, G.R. A tenth anniversary assessment of Davenport and Prusak (1998/2000) Working Knowledge: Practitioner approaches to knowledge in organisations. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2013, 11, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Lee, S.; Kang, I.W. KMPI: Measuring knowledge management performance. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.T.; Lo, M.C.; Suaidi, M.K.; Mohamad, A.A.; Razak, Z.B. Knowledge management process, entrepreneurial orientation and performance in smes: Evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; LaForge, R.W. The emergence of entrepreneurial marketing: Nature and meaning. Entrep. W. Ahead 2001, 1, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y. Analysis of the relationship between open innovation, knowledge management capability and dual innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Ravichandran, T.; Andrevski, G. Information technology, network structure, and competitive action. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 543–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, N.M.; Edeh, F.O.; Islam, K.M.A.; Nitsenko, V.; Polova, O.; Khaietska, O. Utilization of Knowledge Management as Business Resilience Strategy for Microentrepreneurs in Post-COVID-19 Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rigtering, J.P.C.; Hughes, M.; Hosman, V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, M.R.; Wahyudi, S.; Muharam, H.; Thren, A.T.; Robiyanto, R. The role of entrepreneurship oriented finance in improving MSME performance: The demand side of the entrepreneurial finance perspective. Contaduria y Adm. 2022, 67, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonowski, D. Venture capital and entrepreneurial growth by acquisitions: A case study from emerging markets. J. Priv. Equity 2016, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hou, J.; Yang, P.; Ding, X. Entrepreneurial orientation, organizational capability, and competitive advantage in emerging economies: Evidence from China. African J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 3891–3901. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.S.; Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: An empirical investigation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M.; Guenther, C.; Kritikos, A.S.; Thurik, R. Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khlystova, O.; Kalyuzhnova, Y.; Belitski, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: A literature review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1192–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrès, O.; Benzari, A.; Fisch, C.; Mukerjee, J.; Swalhi, A.; Thurik, R. Risk of burnout in French entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 717–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D. The impact of entrepreneurs’ environmental analysis strategy on organizational performance. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Christofi, M.; Tarba, S. Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 1351–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R. Organisational resilience: Development of a conceptual framework for organisational responses. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, P.P.; Pinsonneault, A. Competing perspectives on the link between strategic information technology alignment and organizational agility: Insights from a mediation model. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 35, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Xie, G. Corporate resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of digital finance. Pacific Basin Financ. J. 2022, 74, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulkar, S.; Blackhurst, J.; Grawe, S. Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33–34, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, V.; Basso, O. Exploring the links between entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 18, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.V.; Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Developing a Tool to Measure and Compare Organizations’ Resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2013, 14, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienbacher, A.; Larralde, B. Crowdfunding of small entrepreneurial ventures. In Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance; Forthcomin; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, M.; Liu, W.; Ledger, A.; Zhang, N. What really happens to small and medium-sized enterprises in a global economic recession? UK evidence on sales and job dynamics. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2015, 33, 488–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognazzo, A.; Gubitta, P.; Favaron, S.D. Does slack always affect resilience? A study of quasi-medium-sized Italian firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 768–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, G.; Hogan, T. Bank credit and trade credit: Evidence from SMEs over the financial crisis. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 34, 412–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, E.; Shaw, E. Entrepreneurial marketing—A historical perspective on development and practice. Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, G.E. Marketing and entrepreneurship research issues: Scholarly justification. Res. Mark. Interface 1987, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Becherer, R.C.; Maurer, J.G. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Variables on the Entrepreneurial and Marketing Orientation of Entrepreneur-Led Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1997, 22, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; de Santos, F.M.; Ramalho, I.; Nunes, C. An exploratory study of entrepreneurial marketing in SMEs: The role of the founder-entrepreneur. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaston, I. Small Firm Performance: Assessing the Interaction between Entrepreneurial Style and Organizational Structure. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becherer, R.C.; Helms, M.M.; McDonald, J.P. The Effect of Entrepreneural Marketing on Outcome Goals in SMEs. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2012, 15, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.P. Sample Size Determination and Power; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonowski, D. Strategic Entrepreneurial Finance: From Value Creation to Realization; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Xie, Y.; Hu, S.; Song, J. Exploring how entrepreneurial orientation improve firm resilience in digital era: Findings from sequential mediation and FsQCA. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 27, 96–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.R.A.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.H.M. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S.; Patton, D. Minding the gap between employers and employees: The challenge for owner-managers of smaller manufacturing firms. Empl. relations 2002, 24, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcoulides, G.A. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311766005_The_Partial_Least_Squares_Approach_to_Structural_Equation_Modeling (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Andrews, D.F.; Hampel, F.R. Robust Estimates of Location: Survey and Advances; Princenton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Amato, S.; Vinzi, V.E. A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling. In Proceedings of the XLII SIS Scientific Meeting, Bari, Italy, 9–11 September 2004; pp. 739–742. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C. The impact of entrepreneurs’ oral ‘pitch’ presentation skills on business angels’ initial screening investment decisions. Ventur. Cap. 2008, 10, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald, J.; Bowen, F. Storm clouds and silver linings: Responding to disruptive innovations through cognitive resilience. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.P.; Ungson, G.R. Organizational Memory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.J.; Lai, S.Q.; Ho, C.T. Knowledge management enablers: A case study. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006, 106, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Mocanu, R.; Stanescu, D.F.; Bejinaru, R. The Impact of Knowledge Hiding on Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Mediating Role of Factual Autonomy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebeskind, J.P. Knowledge, strategy, and the theory of the firm. In Knowledge and Strategy; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Organizational Learning Capability and Innovation Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.O. Indigenous knowledge management practices in subsistence farming: A comprehensive evaluation. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, S.S.; Alzahrani, S. The Use of Social Media Platforms for Competitive Information and Knowledge Sharing and Its Effect on SMEs’ Profitability and Growth through Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, J.; Abubakar, Y.A.; Sagagi, M. Knowledge creation and human capital for development: The role of graduate entrepreneurship. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortigueira-Sánchez, L.C.; Welsh, D.H.B.; Stein, W.C. Innovation drivers for export performance. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Kraus, S.; Liguori, E.; Bamel, U.K.; Chopra, R. Entrepreneurial challenges of COVID-19: Re-thinking entrepreneurship after the crisis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 62, 824–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Green, K.M.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic Process Effects on The Entrepreneurial Orientation-Sales Growth Rate Relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodor, S.; Aránega, A.Y.; Ramadani, V. Impact of digitalization and innovation in women’s entrepreneurial orientation on sustainable start-up intention. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R.; Al-Shaikh, M.E.; Joghee, S.; Alzoubi, H.M. Impact of Innovation Capabilities on Business Sustainability in Small and Medium Enterprises. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2022, 11, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyie, S.; Du, J.; Musah, A.-A.I. Innovation and marketing performance of SME in an emerging economy: The moderating effect of transformational leadership. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulka, B.M.; Ramli, A.; Mohamad, A. Entrepreneurial competencies, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial network, government business support and SMEs performance. The moderating role of the external environment. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021, 28, 586–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoa-Gyarteng, K.; Dhliwayo, S.; Adekomaya, V. Innovative marketing and sales promotion: Catalysts or inhibitors of SME performance in Ghana. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2353851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyen, S. The Online Shopping Experience During the Pandemic and After—A Turning Point for Sustainable Fashion Business Management? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 3632–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidle, S.B.; Glass, C.; Rice, M.; Henderson, D.A. Addressing Wicked Problems (SDGs) Through Community Colleges: Leveraging Entrepreneurial Leadership for Economic Development Post-COVID. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Mahmood, A. How Do Supply Chain Integration and Product Innovation Capability Drive Sustainable Operational Performance? Sustainability 2024, 16, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Bansal, P. The long term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalahmadi, M.; Parast, M.M. A review of the literature on the principles of enterprise and supply chain resilience: Major findings and directions for future research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D.; Deakins, D.; Battisti, M. Small business responses to a major economic downturn: Empirical perspectives from New Zealand and the UK. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 3, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Teixeira, E.; Werther, W.B., Jr. Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Dimension | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Management Capability (KMC) [29] | Knowledge management infrastructure, which consists of sub-dimensions: | |

| Technology | Easy to learn, technology as a source of learning information, utilizing technology to compete | |

| Organizational structure | Knowledge interaction and sharing, new knowledge facility, knowledge-sharing reward system | |

| Culture | Believing in mistakes as a source of learning, mutual trust, company encourages asking questions, believing in imitation as a source of learning | |

| Knowledge management process, which consists of sub-dimensions: | ||

| Acquisition | Extracting knowledge from customers, extracting knowledge from partners, extracting knowledge from employees | |

| Conversion | Turning knowledge into products/services, transferring knowledge, absorbing knowledge | |

| Aplication | Easy to practice, saves activity, improves competitive ability | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) [67] | Protection | Protection policy, protection procedures |

| Proactiveness | Initiative, excels at opportunity identification, quick to take action | |

| Innovativeness | Actively innovating, creative business operations, looking for new approaches | |

| Risk-taking | Risk perception, risk-taking, exploration and experimentation for opportunities | |

| Competitive aggressiveness | Competitive business, aggressive competition, outperforming the competition | |

| Autonomy | Employees work independently, employee initiative, employees are given authority and responsibility, employees have access to important information, employees are free to communicate | |

| Entrepreneurial finance (EF) [103] | - | Effective financial resource management entails the mobilization of capital, strategic allocation of resources, risk mitigation, optimization of financial agreements, and the creation and enhancement of value within the context of entrepreneurship |

| Entrepreneurial marketing (EM) ([47]) | Proactiveness | New ways to improve business, different ways of making products, anticipate problems and create opportunities |

| Calculated Risk-Taking | Willing to take risks, can predict risk, analyze environmental conditions | |

| Innovativeness | New innovation, prioritize creativity, changes in design | |

| Opportunity focus | Quick to seize new opportunities, search for new opportunities, knowing market demand information | |

| Resource leveraging | Utilize your closest contacts, work harder, positioning employees with many positions | |

| Customer intensity | Proximity to customers, customer satisfaction, providing new information to customers | |

| Value creation | Creating more value through service, providing something different, use of social media for advertising messages | |

| Business resilience (BR) [104] | Company resilience | The ability to manage and adapt effectively to disruptions in the supply chain, respond swiftly to unexpected challenges, and maintain a high level of situational awareness demonstrates organizational resilience and flexibility in dynamic environments |

| Agility | The capacity to address customer demands effectively, adjust production systems efficiently, make prompt and informed decisions, actively seek information to support organizational restructuring, and interpret market changes as opportunities reflects a dynamic and adaptive organizational approach | |

| Characteristics | Frequency | % | Characteristics | Frequency | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Type of Business | ||||||

| 1. | Male | 92 | 73.6 | 1. | Restaurant | 5 | 0.04 |

| 2. | Female | 33 | 26.4 | 2. | Food stalls | 8 | 6.4 |

| Age | 3. | Culinary carts | 93 | 74.4 | |||

| 1. | <25 years old | 0 | 0 | 4. | Various cakes and snacks | 10 | 12 |

| 2. | 26–35 years old | 35 | 28 | 5. | Beverage/coffee shop | 1 | 3.2 |

| 3. | 36–45 years old | 43 | 34.4 | Number of Workers | |||

| 4. | 46–55 years old | 31 | 24.8 | 1. | 1–3 people | 70 | 56 |

| 5. | >55 years old | 16 | 12.8 | 2. | 4–6 people | 50 | 40 |

| Education background | 3. | 7–9 people | 5 | 4 | |||

| 1. | Elementary school | 3 | 2.4 | 4. | >9 individuals | 0 | 0 |

| 2. | Junior high school | 12 | 9.6 | Work Experience | |||

| 3. | Senior high school | 62 | 49.6 | 1. | 6 years | 33 | 26.4 |

| 4. | Diploma | 20 | 16 | 2. | 7–13 years | 61 | 48.8 |

| 5. | Bachelor | 28 | 22.4 | 3. | 14–20 years | 20 | 16 |

| 6. | Magister | 0 | 0 | 4. | 21–27 years | 10 | 8 |

| 7. | Doctor | 0 | 0 | 5. | >27 years | 1 | 0.8 |

| Variable | KMC | EF | EO | EM | BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMC | 0.855 | ||||

| EF | 0.568 | 0.811 | |||

| EO | 0.544 | 0.694 | 0.881 | ||

| EM | 0.556 | 0.457 | 0.475 | 0.781 | |

| BR | 0.611 | 0.665 | 0.647 | 0.598 | 0.944 |

| Variable | AVE | CR | CA |

|---|---|---|---|

| KMC | 0.731 | 0.961 | 0.936 |

| EO | 0.609 | 0.886 | 0.921 |

| EF | 0.657 | 0.920 | 0.894 |

| EM | 0.776 | 0.960 | 0.972 |

| BR | 0.891 | 0.942 | 0.923 |

| Variable | R2 | Q2 | GoF |

|---|---|---|---|

| EO | 0.296 | 0.128 | 0.565 |

| EF | 0.534 | 0.341 | |

| EM | 0.351 | 0.220 | |

| BR | 0.603 | 0.354 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coeff | T-Statistic | p-Value | f-Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | KMC → OE | 0.544 | 7.710 | 0.000 | 0.421 |

| H2 | OE → EF | 0.547 | 7.675 | 0.000 | 0.452 |

| H3 | OE → EM | 0.245 | 3.097 | 0.001 | 0.065 |

| H4 | OE → BR | 0.227 | 2.573 | 0.005 | 0.061 |

| H5 | EF → BR | 0.287 | 3.082 | 0.001 | 0.096 |

| H6 | EM → BR | 0.259 | 3.438 | 0.000 | 0.109 |

| H7 | KMC → EF | 0.271 | 3.610 | 0.000 | 0.111 |

| H8 | KMC → EM | 0.422 | 5.749 | 0.000 | 0.193 |

| H9 | KMC → BR | 0.181 | 2.369 | 0.009 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charisma, D.; Hermanto, B.; Purnomo, M.; Herawati, T. Building Business Resilience Through Strategic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Culinary Micro-Enterprises in Bandung During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062578

Charisma D, Hermanto B, Purnomo M, Herawati T. Building Business Resilience Through Strategic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Culinary Micro-Enterprises in Bandung During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062578

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharisma, Dinna, Bambang Hermanto, Margo Purnomo, and Tetty Herawati. 2025. "Building Business Resilience Through Strategic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Culinary Micro-Enterprises in Bandung During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062578

APA StyleCharisma, D., Hermanto, B., Purnomo, M., & Herawati, T. (2025). Building Business Resilience Through Strategic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Culinary Micro-Enterprises in Bandung During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 17(6), 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062578