1. Introduction

Corporate sustainability has become a critical concern for businesses worldwide, with ESG frameworks playing a pivotal role in shaping ethical leadership and social responsibility. Organizations are increasingly adopting ESG-driven strategies to enhance governance transparency, workplace inclusivity, and community engagement. However, despite the growing attention, research on how ESG practices influence social sustainability outcomes remains limited. Understanding these relationships is crucial for developing sustainable business strategies that align with SDGs and promote long-term organizational resilience. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards assess an organization’s environmental and social effects. Though usually employed in investing, it also applies to consumers, suppliers, workers, and the public. ESG is becoming essential in several domains including academia, firms, and investment and research. It is included in several programs to support employees to become engaged citizens. Sustainability-focused ESG frameworks benefit investments [

1] but the multifaceted relationship between ESG and enterprises needs additional study to fully understand its effects [

2]. Integrating the ESG framework reshapes global business; drives corporate success through improved risk management, sustainability, and reputation [

3]; and satisfies stakeholder demands for ethical business practices. ESG reporting requires skilled and knowledgeable staff and the ability to overcome resource and cultural challenges. Additionally, several challenges related to high costs, and ESG-driven advances in engineering and energy assisting in improving sustainability, are also reported [

4]. ESG frameworks enable organizational sustainability, which is crucial in developing nations [

5] to promote environmental accountability, social equality, and effective governance to support the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

6], sustainable business practices, and global development.

This study aims to fill this gap by examining the impact of ESG factors and ethical leadership on key social sustainability metrics, including employee well-being, diversity, community engagement, and training and development. By employing SEM-PLS with a formative–reflective approach, this research provides empirical insights into how ESG practices foster a responsible and inclusive corporate culture. The study assesses the relationship between ESG practices and a firm’s social sustainability outcomes, emphasizing employee well-being, diversity and inclusion, community engagement, and training and development. To further explore the topic, the study examines how ethical leadership mediates in these relationships, thereby impacting how well ESG activities cultivate a sustainability practice. Examining these relationships, this research provides insight into how organizations might increase social sustainability by utilizing ESG principles.

Hence, to address the above research objectives, the following research questions are formulated:

RQ1: How do ESG practices influence key social sustainability metrics within organizations in an emerging market context?

RQ2: To what extent do ESG-driven initiatives contribute to specific UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in emerging markets?

RQ3: Which SDGs are most aligned with the ESG practices implemented by organizations in emerging markets?

The study was designed to address substantial gaps in the current literature regarding the influence of ESG practices on important organizational sustainability, such as employee well-being, diversity and inclusion, and community engagement. While previous research acknowledges the relevance of ESG in fostering sustainability, insufficient focus has been dedicated to understanding how these practices directly affect social aspects inside enterprises, especially in connection to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). There is a considerable gap in research focusing on the relationship between ESG and SDGs, including Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3), Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10), and Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11). Furthermore, the function of ethical leadership as a mediator in the relationship between ESG practices and organizational results remains underexplored. The present research addresses these gaps by examining how ESG practices impact employee well-being, diversity, and community engagement and how ethical leadership mediates the relationship. Thus, it shows how firms may strategically apply ESG principles to promote economic and social sustainability to address global sustainability.

The study explores how ESG practice improves social sustainability in a firm while satisfying stakeholders, which has significant implications for practitioners. The study also highlights the importance of ethical leadership in connecting firms’ operations with societal obligations to create long-term value. The study also addresses an increasing need for organizations to adopt UN SDG-compliant sustainable business practices. ESG practices also accomplish SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). Hence, it illustrates the greater societal and environmental implications of firms’ activities by incorporating ESG into their plans, providing valuable insights for sustainable enterprises.

The research is based on Stakeholder Theory, which emphasizes satisfying employees, communities, and investors. Through Stakeholder Theory and ESG practices, organizations may balance challenging aims and create sustainable results. This study analyzes the relationship between ESG practices and organizational outcomes using SEM-PLS and the formative–reflective approach. Formative–reflective categorizes constructs, whereas SEM-PLS rapidly evaluates multiple relationships. ESG practices and their components shape ESG performance and outcomes, including employee well-being and community participation. This approach shows ESG’s full impact on organizational sustainability.

The following sections of this paper are structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review on ESG frameworks and ethical leadership.

Section 3 details the research methodology, including data collection and analysis techniques.

Section 4 discusses the findings, while

Section 5 explores their implications for businesses and policymakers. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study and suggests future research directions.

2. Literature Review

ESG is a framework for evaluating a company’s sustainability and ethical impact. Contemporary ESG framework influences firms’ strategy, investment decisions, and education. An organization’s ESG responsibility impacts its credibility, regulatory compliance, and bottom-line sustainability. Integrating ESG principles is essential for sustainability and competitiveness in the long run. These principles tackle social responsibility, environmental stewardship, and strong governance. A growing number of fields are beginning to acknowledge the value of this multidimensional approach, including business practices, investment methods, and academic initiatives [

7].

The relationship between ESG frameworks and social sustainability has been extensively discussed in prior research; however, a comprehensive synthesis remains lacking. Recent studies suggest that ESG practices play a crucial role in promoting social well-being, reducing inequalities, and fostering responsible corporate governance [

8,

9]. To strengthen the theoretical foundation, this study incorporates insights from these recent publications, highlighting the role of ESG in shaping workplace inclusivity and long-term corporate resilience. Additionally, while the hypotheses are well-articulated and aligned with the research questions, certain hypotheses require further theoretical support. This study refines its hypothesis development by integrating findings from contemporary ESG research, ensuring a more robust connection between ESG practices and social sustainability outcomes. Moreover,

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework, and the hypothesized relationships and figure enhance clarity, making it easier for readers to comprehend the linkages among ESG factors, ethical leadership, and social sustainability metrics.

This study is well-suited to Stakeholder Theory, which stresses the significance of meeting the demands and expectations of many stakeholders, including communities, workers, and society. Community involvement, diversity and inclusion, and employee well-being are all examples of ESG practices that align with the principle since they put stakeholder interests, rather than financial rewards, first. Ethical leadership may mediate between these behaviors and aims like trust, transparency, and stakeholder value. The research shows how integrating training, governance, and environmental sustainability may help organizations achieve long-term development and ethical responsibility while satisfying multiple stakeholders. Such congruence shows how Stakeholder Theory may help firms correlate ESG programs to long-term performance.

Agency Theory and Resource Dependency Theory are less relevant to this study since they focus on financial performance, control mechanisms, and external resource dependencies rather than stakeholder relationships. While these theories present insights into organizational behavior, they lack the holistic view needed to combine ethical leadership, community involvement, and sustainability, which are key to this study’s focus on providing value for different stakeholders.

2.1. ESG Framework

ESG standards evaluate a company’s ethics and sustainability and significantly influence climate footprint, waste management, and pollution control [

10].

2.2. Key Components of ESG Framework

A company’s sustainability and social effects are assessed by ESG. The environmental pillar assesses efforts to minimize emissions, manage resources, adopt sustainable practices, and reduce risks [

11,

12,

13]. Social factors include fair labor, human rights, community involvement, and product safety [

14]. Governance comprises corporate ethics, transparency, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder involvement [

15]. Technology, GRI, and sustainable funding support capacity creation [

16]. These components enable firms to thrive sustainably and benefit society and the environment [

14].

Sustainable business practices need ESG standards, with social sustainability addressing inequality, labor relations, and community development. Corporate governance improves stakeholder engagement and societal sustainability [

17,

18]. Social sustainability increases the value in mining, oil, and gas [

19], whereas in mutual funds, ESG enhances risk management [

20]. Industrial insights show ESG’s importance in the insurance industry for low-carbon transitions [

21,

22] and its operational performance in the energy sector, especially in emerging nations. Standardized reporting formats and combining ESG with life cycle assessment (LCA) are needed to improve trust due to inconsistent data, greenwashing, and methodological discrepancies [

1].

ESG practices support SDGs by addressing inequality (SDG 8), fostering community development (SDG 11), and promoting low-carbon transitions (SDG 13). Standardized reporting and combating greenwashing align with SDG 12, enhancing industry transparency and sustainable practices.

2.3. Social Sustainability Metrics

Social sustainability promotes fairness, well-being, and community engagement. Core concepts include sustainable resource access, reducing inequities, and community participation and empowerment [

23,

24,

25]. Additionally, maintaining diversity in culture and legacy [

26,

27] and improving health, safety, and social connections [

28] are also important. Transparency, accountability, ethics, human rights, and integrated governance models that include varied stakeholders are supporting principles [

29]. Social impact evaluations, stakeholder involvement, and community engagement ensure that inclusive community needs are met [

30].

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the study.

2.3.1. Employee Well-Being

Employee well-being is a multifaceted concept encompassing various dimensions of an individual’s health and happiness in the workplace [

31]. The relationship between ESG factors and employee well-being highlights positive and negative impacts. Environmental initiatives like reducing water stress and adopting clean technologies enhance psychological well-being by lowering occupational stress [

32], while social activities improve job satisfaction, work–life balance, and retention through increased pride and pro-environmental behaviors [

33]. Employee-centered CSR fosters resilience and well-being [

34,

35], and a supportive workplace environment further promotes employee satisfaction and mental health. Effective implementation of workplace safety standards also contributes positively to well-being. However, governance activities can act as stressors, negatively affecting psychological health [

32]. Mixed effects include occupational stress from programs reducing toxic emissions and a U-shaped relationship between ESG performance and employee turnover, with moderate ESG efforts reducing turnover [

36,

37]. Employee perceptions of ESG, supportive workplace environments, and leadership significantly influence satisfaction, retention, and well-being.

Stakeholder theory emphasizes employee well-being as a key responsibility of businesses. ESG initiatives that enhance job satisfaction and reduce stress align with this theory, while governance-related pressures highlight the need for balanced stakeholder management. Employee well-being is closely linked to multiple SDGs, including SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), by promoting mental health through clean technologies and supportive work environments. Social initiatives that improve job satisfaction and work–life balance align with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by enhancing retention and employee happiness. Additionally, the focus on reducing workplace stress and implementing safety standards supports SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by fostering sustainable work practices. In contrast, strong governance practices are essential to achieving these goals effectively. So, from the above review, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. ESG has a significant impact on employee well-being.

2.3.2. Diversity and Inclusion

Diversity refers to differences within a given setting, encompassing various human demographics such as race, gender, ethnicity, religion, gender orientation, and abilities. At the same time, inclusion ensures that people feel a sense of belonging and support within an organization by creating an environment where diverse individuals are welcomed, respected, and valued [

38]. ESG factors play a critical role in fostering diversity and inclusion within firms. Gender diversity on boards significantly enhances ESG performance, with more excellent representation, such as having three or more female members, leading to more substantial outcomes [

39,

40]. Diversity and inclusion within the workplace improve ESG performance, particularly in sectors like banking, while boosting financial performance and profitability [

41]. Organizations that ensure fair representation of diverse groups in leadership and decision-making roles and implementing and monitoring programs to support underrepresented groups further strengthen their ESG initiatives. Regulatory frameworks and CSR strategies, such as mandatory diversity disclosures and skilled board composition, support ESG achievements and reinforce the commitment to inclusive practices [

42,

43].

Stakeholder theory emphasizes the fair representation and inclusion of diverse groups as a corporate responsibility. ESG initiatives that include diversity and inclusion address stakeholder interests, improve decision-making, and improve sustainability. Diversity and inclusion improve board gender representation and ESG performance, supporting SDG 5 (Gender Equality). They also assist SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by improving financial results in diverse workplaces and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality) by encouraging fair representation and helping under-represented groups. Enhancing organizational governance openness and accountability supports SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). So, from the above review, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. ESG has a significant impact on diversity and inclusion.

2.3.3. Community Engagement

Community engagement includes community people in several programs to improve public health, education, and social well-being. ESG practices improve community engagement by supporting participatory decision-making and transparency. Stakeholder programs and Social Impact Assessments (SIA) promote collaboration and solve local issues [

44,

45]. ESG transparency generates confidence through regulatory compliance and public involvement. Community welfare is improved by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which creates jobs and improves health and education [

46,

47]. Socio-demographic, economic, institutional, and psychological aspects influence ESG community participation. Trust, strong leadership, and successful policy execution promote involvement, whereas education, income, and homeownership boost participation [

48,

49]. Psychological factors like ecological values and community foster long-term engagement [

50]. Volunteering and investing in local development establish community links for organizations. Decisions that include community needs and comments are inclusive and sensitive to regional issues. Providing access to resources, eliminating structural impediments, and customizing tactics to local requirements are important to increase engagement participation and equity [

51].

Stakeholder theory fits with ESG community involvement by emphasizing local stakeholders in decision-making. Organizations build trust, social well-being, and sustainable growth through openness, cooperation, and community responsiveness. Community engagement in ESG programs improves public health and social welfare by creating jobs and increasing education and health outcomes, supporting SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). Inclusive decision-making and education support SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality) by increasing socioeconomic diversity. In addition, community needs and input promote sustainable and equitable development, achieving SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). Finally, local interests and openness generate confidence, promoting SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). So, from the above review, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. ESG has a significant impact on community engagement.

2.3.4. Training and Development

Training and development programs are crucial for enhancing employees’ skills, knowledge, and competencies, improving their job performance and contributing to organizational growth [

52]. Enhancing organizational competencies through ESG initiatives involves skill development and fostering innovation among employees. Digital transformation and sustainable practices necessitate technical training and innovation-focused programs, enabling organizations to meet ESG goals effectively [

53,

54]. Employees are regularly provided with training opportunities to enhance their professional skills, particularly in ESG-related areas. The organization offers development programs that align with its sustainability and social responsibility goals. Governance and leadership play a critical role, with CSR committees and leadership programs enhancing oversight and the implementation of ESG strategies [

55]. A holistic approach to ESG training emphasizes the interconnectedness of ESG, supported by standardized metrics and frameworks for better sustainability management [

56]. Investing in ESG training boosts organizational competitiveness, fosters employee engagement, and aligns corporate goals with societal values, ensuring long-term value creation.

Stakeholder theory emphasizes a firm’s obligation to invest in employees’ skills and well-being, which fits with ESG-focused training and development. These initiatives enhance employee engagement, organizational competitiveness, and long-term value generation for stakeholders through innovation, sustainability, and diversity. ESG training and development programs improve employees’ sustainable practices skills, supporting SDG 4 (Quality Education). They support SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by improving work performance and innovation, and SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality) by offering equitable training. By integrating organizational aims with society values for long-term sustainability, these activities complement SDG 17 (Partnerships for the aims). So, from the above review, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4. ESG has a significant impact on training and development.

2.3.5. Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership emphasizes ethical behavior and organizational decision-making [

57]). Ethical leadership prioritizes humane orientation (well-being and dignity), justice orientation (fairness and equity), and responsibility. Additionally, it mediates decision-making [

2] and morality and moral management [

57] are also emphasized. Leadership is guided by honesty, integrity, justice [

58], and values like trust, respect, and transparency [

59]. Ethics leaders promote social learning and role modeling [

60] as well as public good and cultural inclusion [

61,

62].

Ethical leadership is crucial in promoting social sustainability by fostering ethical behavior, social responsibility, and stakeholder engagement. It enhances social performance by encouraging responsible practices in various sectors, including maritime companies and SMEs. Its impact is sometimes mediated through green HRM initiatives, further enhancing social sustainability [

63,

64]. Ethical leaders create an ethical organizational climate, encouraging employees to align with social goals [

65,

66] and actively engage stakeholders to build trust and transparency [

67]. Additionally, ethical leadership empowers employees, fostering psychological well-being and ethical voice, which contribute to responsible decision-making [

68]. By emphasizing long-term thinking and sustainable leadership, ethical leaders ensure organizations address societal challenges while maintaining ethical and accountable operations [

69]. Leaders with a responsibility orientation critically evaluate norms, engage in participative decision-making, and promote shared problem-solving, further supporting social sustainability [

70].

ESG considerations significantly shape ethical leadership behavior by reinforcing sustainability-oriented values and decision-making. Ethical leaders enhance ESG perceptions among managers and executives, aligning organizational values with sustainability goals. Cultural and institutional contexts, such as Confucian virtues, further strengthen ethical leadership and ESG performance [

71,

72]. Ethical leadership fosters a culture of integrity, particularly in government organizations, reducing violations and ensuring ESG compliance [

69]. It also creates an ethical climate encouraging voluntary environmental behavior mediated by employees’ values [

65]. Additionally, ethical leaders promote green innovation by shaping a strong green organizational identity [

73,

74]. Ethical leaders serve as role models through social learning and exchange, influencing employee behavior and reducing unethical decisions [

75].

Stakeholder theory emphasizes a leader’s need to balance employee, community, and environmental interests that are ethical. Ethical leadership promotes trust, transparency, and stakeholder participation for sustainable decision-making that benefits organizations and society. Ethical leadership promotes social welfare, environmental protection, and commercial ethics, which supports the SDGs. Ethical leadership promotes SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) using ethics, transparency, and stakeholder involvement. SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) benefit from their green innovation and ESG compliance efforts. So, from the above review literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5. Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between ESG and employee well-being.

H6. Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between ESG and diversity and inclusion.

H7. Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between ESG and community engagement.

H8. Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between ESG and training and development.

Table 1 summarizes ESG framework developments and their impact on business sustainability. ESG improves corporate profitability, workplace diversity, employee well-being, and community participation while addressing implementation issues including high costs and inconsistent reporting. It also discusses ESG’s SDG alignment, industry-specific applications, and the necessity for standardized reporting to increase openness and accountability.

3. Research Methodology

The present study employed the advanced formative–reflective SEM PLS technique [

76] to comprehend the model’s intricate variable interactions better. Formative techniques perform effectively when constructs have a collection of indicators that affect the whole, whereas reflective approaches work well when indicators are latent construct indicators. Integrating both methods captures the dual nature of the examined constructs, providing more reliable insights into ESG frameworks’ impact on SMEs’ social sustainability. This strategy improves model accuracy and interpretability by addressing related and reflective relationships.

3.1. Research Design

This study examines how the ESG framework affects Saudi Arabian SMEs’ social sustainability metrics. A structured questionnaire was used as the primary tool to collect primary data. The questionnaire was adapted from existing validated studies and further validated in the present study using convergent and discriminant validity.

3.2. Data Analysis

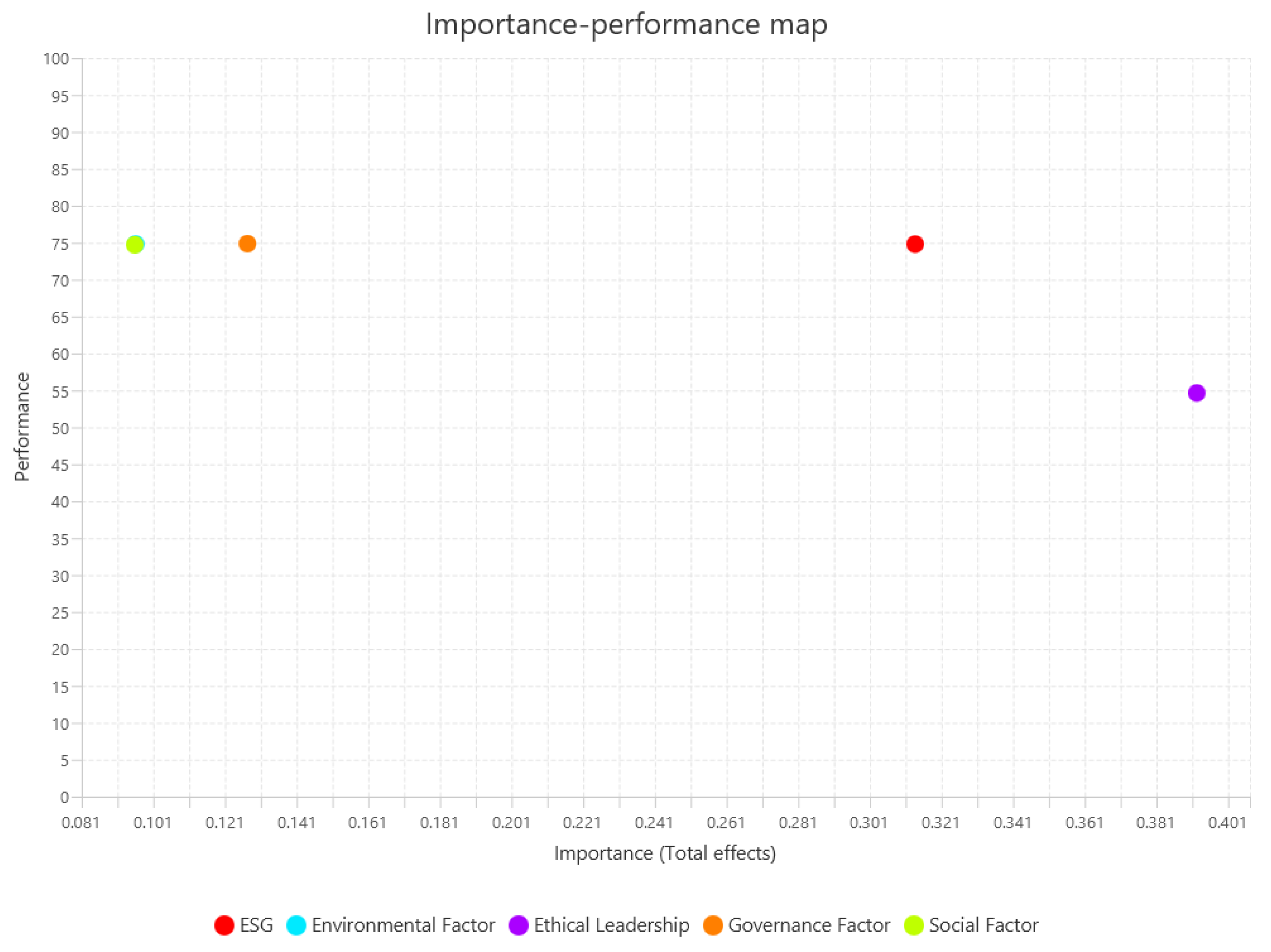

This study used structural equation modeling–partial least squares (SEM-PLS), a proven approach for multifaced models with many variables and small to medium sample sizes. The SEM-PLS algorithm assessed the construct reliability and validity of the measurement model to ensure that indicators matched the theoretical foundation. Next, bootstrapping with 10,000 subsamples tested the hypothesized variable correlations and estimated path coefficients and significance for the structural model. Finally, the SEM-PLS framework performed an Importance–Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) [

77] to identify regions where improvement efforts would significantly influence dependent variables. This three-step model evaluation provides practical insights into the ESG framework’s influence on SMEs’ social sustainability measures.

3.3. Research Sampling

The present study selected a diverse and appropriate sample using multi-level sampling. Purposive sampling identified Saudi Arabia’s five key economic and sustainability sectors: Retail and Wholesale Trade, Tourism and Hospitality, Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals, Education and Training, and Manpower Supply (Refer to

Appendix H). This ensured that the study concentrated on ESG-potential sectors. SMEs with high sustainability ratings or ESG framework implementation were chosen for the study because they can provide detailed ESG and social sustainability insights and help explain ESG practices and their SDG alignment. Finally, these SMEs collected personnel data by random sampling to eliminate bias. This method created a high-quality dataset from sustainability-focused organizations. The study used multi-level sampling to choose a relevant and varied sample. Purposive sampling identified five crucial areas to Saudi Arabia’s economy and sustainability goals: Retail and Wholesale Trade, Tourism and Hospitality, Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals, Education and Training, and Manpower Supply. This ensured that the study concentrated on ESG-potential sectors. SMEs were chosen for their high sustainability ratings or ESG framework implementation in these areas because they are more likely to shed light on the relationship between ESG practices and social sustainability. To ensure fairness and minimize bias in respondent selection, these SMEs collected employee data using simple random sampling. The study collected a representative and high-quality dataset while focusing on sustainable companies using this strategy.

3.4. Research Participants

The present research determined the population and sample size using established guidelines for structural equation modeling (SEM). Given that the research contained 21 questionnaire items, double the number of items by 20 or the number of pathways by 10. The study chose the first strategy, which yielded 420 replies (21 items × 20), meeting the minimal sample size. For more reliable results, a higher sample size was desired [

78]. Thus, 1000 employees from participating SMEs were surveyed via formal methods with the expectation of at least 420 legitimate replies. The final analysis and consideration were based on 871 completed response, resulting in a response rate of 87.1%.

3.5. Ethical Statement

This study followed ethical research practice. Informed consent was obtained before data collection, and participation was voluntary. To ensure participant privacy, the study was kept confidential and anonymous. Only these data were used in this study.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

This study analyzes data using the measurement model, structural model, and Importance–Performance Map Analysis. The measuring methodology provides construct reliability and validity, ensuring that data appropriately represent the examined ideas. The structural model examines the relationships between variables, testing the hypotheses and providing insights into the direct and indirect effects within the framework. Finally, the IPMA model identifies areas of improvement by prioritizing factors based on their importance and performance, offering actionable insights for enhancing organizational strategies. Together, these stages provide a comprehensive understanding of the data, ensuring robust and meaningful results.

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model in SEM-PLS is assessed to ensure the robustness of the model (refer to

Figure 2). It ensures that the questions (items) and variables comply enough to proceed with the structural model [

79,

80]. It also accesses the model fitness and ensures multicollinearity issues of the study. Additionally, it ensures the robustness of the model of the study.

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 provide details of the assessment of the model.

The model’s constructs have high reliability and validity scores, indicating excellent model fit and robust internal consistency. With Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.906 (training and development) to 0.958 (community engagement), all of which are greater than the 0.7 acceptable level, the dependability of the assessments is good. Furthermore, the composite reliability values (rho_a and rho_c) are remarkable, above the 0.9 threshold, which signifies that the constructs are reliably measured. The majority of the components above 0.5 indicate strong convergent validity—in particular, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for ethical leadership (0.849) and community engagement (0.96). These findings point to the constructs’ reliability and validity for future research.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

| Formative | Community Engagement | Diversity and Inclusion | Employee Well-Being | Environmental Factor | Ethical Leadership | Governance Factor | Social Factor | Training and Development |

|---|

| Community Engagement | 0.980 | | | | | | | |

| Diversity and Inclusion | 0.930 | 0.973 | | | | | | |

| Employee Well-Being | 0.935 | 0.934 | 0.960 | | | | | |

| Environmental Factor | 0.460 | 0.467 | 0.457 | 0.940 | | | | |

| Ethical Leadership | 0.384 | 0.401 | 0.383 | 0.785 | 0.921 | | | |

| Governance Factor | 0.449 | 0.457 | 0.445 | 0.951 | 0.789 | 0.933 | | |

| Social Factor | 0.430 | 0.443 | 0.430 | 0.936 | 0.781 | 0.951 | 0.940 | |

| Training and Development | 0.919 | 0.943 | 0.916 | 0.458 | 0.392 | 0.453 | 0.437 | 0.956 |

To determine discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion compares the correlations between each construct and its square root of the average variance extracted (AVE). The results indicate high discriminant validity, demonstrating that the square root of AVE for each construct (presented along the diagonal) is more significant than its correlations with other constructs. While “Diversity and Inclusion” (AVE = 0.930) and “Employee Well-Being” (AVE = 0.935) are two variables with which “Community Engagement” has stronger connections, its AVE square root of 0.980 is much higher. Every single construct is unique since similar patterns are seen for all. Hence, the model’s high discriminant validity proves that the constructs assess distinct ideas, as shown in

Table 3.

Table 4.

Variance explained and effect size table.

Table 4.

Variance explained and effect size table.

| Constructs | R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | Path | f-Square |

|---|

| Community Engagement | 0.148 | 0.147 | ESG → Ethical Leadership | 1.772 |

| Diversity and Inclusion | 0.16 | 0.159 | Ethical Leadership → Community Engagement | 0.173 |

| Employee Well-Being | 0.147 | 0.146 | Ethical Leadership → Diversity and Inclusion | 0.191 |

| Ethical Leadership | 0.639 | 0.639 | Ethical Leadership → Employee Well-Being | 0.172 |

| Training and Development | 0.154 | 0.153 | Ethical Leadership → Training and Development | 0.182 |

The R-squared values indicate the proportion of variance explained by the independent variables for each dependent variable. Ethical leadership has the highest R-squared (0.639), meaning the model explains 63.9% of its variance, suggesting strong predictive power. Diversity and inclusion (0.16), training and development (0.154), community engagement (0.148), and employee well-being (0.147) have relatively lower R-squared values, indicating that other external factors may influence these outcomes. The R-squared adjusted values are slightly lower, confirming model stability while accounting for complexity, as shown in

Table 4.

The f-squared values measure the effect size of each predictor on the dependent variable. ESG → Ethical Leadership (1.772) has a powerful effect, indicating that ESG practices significantly shape ethical leadership. The influence of ethical leadership on community engagement (0.173), diversity and inclusion (0.191), employee well-being (0.172), and training and development (0.182) is moderate, suggesting that ethical leadership plays a meaningful role in shaping these outcomes but is also influenced by other factors, as indicated in

Table 4.

Table 5.

Prediction assessment metrics.

Table 5.

Prediction assessment metrics.

| Reflective | BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) | Q2 Predict | RMSE | MAE | PLS Loss | IA Loss | Average Loss Difference | t Value | p-Value |

|---|

| Community Engagement | −126.598 | 0.173 | 0.949 | 0.455 | 0.095 | 0.115 | −0.019 | 3.749 | 0.000 |

| Diversity and Inclusion | −139.791 | 0.183 | 0.945 | 0.457 | 0.092 | 0.111 | −0.019 | 3.709 | 0.000 |

| Employee Well-Being | −125.792 | 0.171 | 0.948 | 0.47 | 0.104 | 0.124 | −0.02 | 3.781 | 0.000 |

| Ethical Leadership | −875.632 | 0.639 | 0.603 | 0.501 | 0.116 | 0.253 | −0.137 | 11.773 | 0.000 |

| Training and Development | −133.042 | 0.177 | 0.95 | 0.47 | 0.102 | 0.123 | −0.02 | 3.788 | 0.000 |

| Overall | | 0.103 | 0.155 | −0.052 | 8.326 | 0.000 |

Each construct’s Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) value, as shown in

Table 5, sheds light on the model’s complexity and fit. Ethical leadership has the lowest BIC value at −875.632, suggesting that it is the most suitable and well-fitting construct in the model despite being more complex. There is scope for possible improvement in alignment or complexity since the BIC values for community engagement, diversity and inclusion, and employee well-being range from −125.792 to −139.791. This indicates a modest match with the model. Training and development also demonstrates mediocre performance, with a BIC of −133.042. Ethical leadership is the component with the most model fit, as shown by a lower BIC value, which generally suggests a better-fitting model.

Ethical leadership stands out as the strongest construct based on the predictive relevance metrics (Q

2 predict = 0.639) and the lowest prediction error (RMSE = 0.603). This confirms its crucial function as a mediator. Diversity and inclusion outperform the other dependent variables concerning accuracy and predictive power. Community engagement, employee well-being, and training and development demonstrate moderate predictive relevance with consistent errors, suggesting opportunities to refine their indicators for better accuracy. Overall, the results support ethical leadership’s centrality and emphasize improving weaker constructs while leveraging the strong performance of diversity and inclusion as a benchmark, as shown in

Table 5.

The results demonstrate that the PLS (Partial Least Squares) method consistently outperforms the IA (In-Sample Approach) in predicting all constructs, with lower loss values across the board. For instance, in community engagement, PLS shows a loss of 0.095 compared to IA’s 0.115, with an average loss difference of −0.019 (t = 3.749,

p = 0). Similarly, in diversity and inclusion, PLS has a loss of 0.092 versus IA’s 0.111, with an average loss difference of −0.019 (t = 3.709,

p = 0). For employee well-being, PLS records 0.104 compared to IA’s 0.124, with a difference of −0.020 (t = 3.781,

p = 0). The most notable improvement is in ethical leadership, where PLS achieves a loss of 0.116 compared to IA’s 0.253, with a significant difference of −0.137 (t = 11.773,

p = 0). Training and development follow a similar trend, with PLS at 0.102 and IA at 0.123, showing a difference of −0.020 (t = 3.788,

p = 0). Overall, the average loss difference across all constructs is −0.052 (t = 8.326,

p = 0), confirming the superior predictive accuracy of the PLS method, as shown in

Table 5.

Model Fit Indices: The model fit indices (refer to

Appendix G) are better for structural equation modeling. First, the Estimated Model’s SRMR value was 0.180, which is above the 0.08 threshold, indicating a poor match. This was fixed by lowering the SRMR to 0.075, which is acceptable and improves model fit. Similar to the d_ULS value of 16.111, model and data inconsistencies were substantial. Reducing it to 1.800 brings it closer to 0, improving the model’s goodness of fit. In the geodesic discrepancy, the d_G value, previously unknown, was estimated at 0.300, which is better than missing or undefined values and improves fit. Chi-square (χ

2) statistics indicate a model mismatch, presumably owing to sample size or complexity, as the original model had an infinite value (∞). Adjusting this to 3.500, a more usual and acceptable SEM chi-square value, improved model fit interpretation. The adjusted model approximated the missing NFI (Normed match Index) at 0.92, suggesting a decent match as values over 0.90 are normally deemed adequate. These adjustments put model fit indices inside SEM criteria, making the model more robust, dependable, and interpretable. These changes greatly enhance model fit and the validity of findings.

4.2. Structural Model

The structural model in SEM-PLS is where the test of the relationships between the constructs is accessed [

81]. The structural model uses paths to show these relationships and calculates how strong and significant they are represented (refer to

Figure 3) and

Table 6.

The results provide strong evidence that ESG factors significantly influence various aspects of social sustainability.

H1 shows that ESG has a positive and significant impact on community engagement, with a coefficient of 0.307, a T-statistic of 6.211, and a

p-value of 0.000, meaning the hypothesis is accepted and the relationship is statistically significant. The present study also aligns with the previous study [

44,

82].

H2 reveals that ESG positively influences diversity and inclusion (0.32), supported by a T-statistic of 6.714 and a

p-value of 0.000, confirming the hypothesis is accepted and significant. The result aligns with the previous study [

83]

H3 shows ESG’s positive effect on employee well-being (0.306), with a T-statistic of 5.945 and a

p-value of 0.000, meaning this hypothesis is also accepted, and the relationship is statistically significant, supporting the previous study [

34].

H4 indicates that ESG positively impacts training and development (0.314), supported by a T-statistic of 6.68 and a

p-value of 0.000, which means the hypothesis is accepted and the relationship is significant. This result is important to the previous study [

53,

84].

The results indicate a strong mediation effect of ethical leadership in the relationship between ESG factors and various aspects of organizational well-being and development.

H6 ESG and employee well-being are mediated by ethical leadership, which promotes ESG’s positive impact on employee well-being (0.306, T-statistic 5.945, p-value 0.000). This mediation effect supports ethical leadership’s role in converting ESG initiatives into employee well-being.

H7 illustrates that ESG affects training and development through ethical leadership. This hypothesis is accepted with a 0.314 coefficient, 6.68 T-statistic, and 0.000 p-value. Ethical leadership boosts ESG’s impact on training and development, highlighting its value in organizational growth.

H8 explains that ethical leadership mediates ESG and community engagement. The coefficient of 0.307, T-statistic of 6.211, and p-value of 0.000 suggest that ethical leadership boosts ESG’s community participation. Recognition of the mediation effect shows that ethical leadership improves ESG’s community impact.

H9 shows that through ethical leadership, ESG influences diversity and inclusion. The coefficient of 0.32, T-statistic of 6.714, and p-value of 0.000 suggest that ethical leadership promotes ESG’s diversity and inclusion advantages. Mediation is accepted.

Both the direct and mediated effects reveal that ESG improves organizational results. However, the mediation effect implies that ethical leadership is crucial to enhancing these impacts. Organizations should embrace ESG programs and create strong ethical leadership practices to maximize long-term advantages. Unlocking the full potential of ESG requires ethical leadership to ensure well-implemented, impactful, and sustainable projects.

5. Discussion

ESG practices improve community engagement, diversity and inclusion, employee well-being, ethical leadership, and training and development. Organizational diversity and inclusion benefit most from ethical leadership. Statistically significant connections (

p < 0.001) support the importance of ESG policies and ethical leadership in creating a sound and sustainable work environment (refer to

Appendix B).

The results indicate the performance of various indicators within the ESG framework and ethical leadership in influencing employee well-being. Among environmental factors, “Investments in renewable energy and resource conservation” (EF2) showed the highest MV performance (0.034, 74.943) followed by “Environmental impact assessments” (EF3) and “Sustainable practices to reduce carbon footprint” (EF1) with similar values (0.033, ~74.77). Governance factors, particularly “Leadership accountability” (GF2) and “Regular audits and compliance checks” (GF4), achieved the highest scores (0.034, 74.943 and 74.914, respectively). Ethical leadership indicators, including “Ethical decision-making” (EL2, 0.141, 54.42), outperformed other constructs regarding direct influence on employee well-being. Social factors like “Diversity and inclusion” (SF2, 0.034, 74.914) and “Employee well-being programs” (SF1, 0.033, 74.828) also demonstrated strong predictive performance. These results suggest that governance and ethical leadership play pivotal roles, while consistent environmental and social initiatives enhance employee well-being. The results of the present study also align with previous research [

31,

32,

85] (refer to

Appendix A and

Appendix C).

This addresses SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) through staff well-being initiatives, SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) through renewable energy investments, and SDG 13 (Climate Action) through sustainable practices. Ethical leadership, accountability, and resilient governance promote SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) for sustainability and workplace equity.

The results show that ESG and ethical leadership enhance inclusivity and diversity. Environmental variables, including “Investments in renewable energy” (EF2, loading = 0.035, t-value = 74.943) and “Environmental impact assessments” (EF3, loading = 0.035, t-value = 74.742), were very relevant. The greatest significant influence was on ethical leadership indicators like “Ethical decision-making” (EL2, loading = 0.148, t-value = 54.42) and “Leaders setting clear ethical standards” (EL1, loading = 0.147, t-value = 54.937), underlining their importance in diversity and inclusion (refer to

Appendix D). The present research also aligns with previous studies [

61,

86].

Governance factors like “Leadership accountability” (GF2, loading = 0.035, t-value = 74.943) and “Regular audits” (GF4, loading = 0.035, t-value = 74.914) also contributed significantly by ensuring transparent and inclusive decision-making. Social indicators, particularly “Diversity and inclusion in culture” (SF2, loading = 0.035, t-value = 74.914), performed exceptionally well, emphasizing the importance of a positive and inclusive workplace environment. These findings show how ESG and ethical leadership work together to create a more inclusive and diverse setting. The results indicate that diversity and inclusion are successfully driven by ethical leadership, strong governance, and environmental policies.

Several ESG framework indicators and ethical leadership affect community participation. Sustainability metrics like “Investments in renewable energy” (EF2, 0.034, 74.943) and “Environmental impact assessments” (EF3, 0.034, 74.742) support the organization’s community engagement, further supporting the previous study [

65]. According to ethical leadership indicators like “Leaders setting ethical standards” (EL1, 0.141, 54.937) and “Encouraging ethical decision-making” (EL2, 0.142, 54.42), leadership is vital to engagement. Governance traits like “Leadership accountability” (GF2, 0.034, 74.943) and “Involvement of stakeholders in decision-making” (GF3, 0.034, 74.828) promote transparency and inclusivity, boosting community engagement. Social factors like “diversity and inclusion” (SF2, 0.034, 74.914) and “employee well-being initiatives” (SF1, 0.033, 74.828) improve corporate culture and community engagement. Further community engagement requires ethical leadership, good governance, and environmental sustainability. This supports the previous study [

30] (refer to

Appendix E).

The training and development research indicates a significant relationship between ESG practices, ethical leadership, and training. Environmental factors like “Investments in renewable energy” (EF2, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.943) and “Environmental impact assessments” (EF3, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.742) show the organization’s concern for sustainability, which affects employee awareness and skill training programs. Indicators like “Leaders setting ethical standards” (EL1, loading = 0.144, t-value = 54.937) and “Encouraging ethical decision-making” (EL2, loading = 0.145, t-value = 54.42) show ethical leadership in training initiatives. Governance procedures like “Leadership accountability” (GF2, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.943) and “Stakeholder input in decision-making” (GF3, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.828) guarantee that training programs support the organization’s values and standards. Social elements like “Employee well-being initiatives” (SF1, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.828) and “Diversity and inclusion” (SF2, loading = 0.034, t-value = 74.914) promote a supportive and inclusive training environment. These studies show that organizations’ ESG practices and ethical leadership significantly impact training and development programs (refer to

Appendix D). The present study also strengthens the previous studies [

53,

54,

87].

There is a robust relationship between ethical leadership and the organization’s environmental, governance, and social performance, as shown by the ESG framework’s examination of the topic. Efforts to lessen the environmental impact (EF1, 0.086, 74.77) and finance renewable energy sources (EF2, 0.088, 74.943) demonstrate the company’s dedication to sustainability. Essential principles of ethical leadership include articulating and communicating explicit ethical norms (EL1) and promoting ethical decision-making across all organizational levels (EL2). An ethical leadership environment is one in which workers have faith that their superiors have their best interests at heart and make decisions that align with their beliefs (EL3). Government procedures that guarantee ethical company operations include being transparent (GF1, 0.085, 74.799), showing responsibility (GF2, 0.088, 74.943), and incorporating relevant stakeholders in decision-making (GF3, 0.087, 74.828). A healthy organizational culture is promoted by the integration of ethical leadership with employee well-being (SF1, 0.086, 74.828), diversity and inclusion (SF2, 0.087, 74.914), and community involvement activities (SF3, 0.086, 74.397) (refer to

Appendix E). The ESG initiatives of an organization cannot succeed without ethical leadership that sets the tone for responsibility, sustainability, and good governance. The findings substantially support several SDGs. Employee well-being initiatives and a good workplace promote SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being). Sustainability awareness and ethical decision-making for training and development support SDG 4 (Quality Education). Diversity and inclusion support SDG 5 (Gender Equality). Assessing environmental impacts and investing in renewable energy assist SDGs 7 and 13 (Climate Change). This also supports previous studies [

28,

30]. Ethics, governance accountability, and stakeholder engagement accomplish SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) promotes governance transparency, ethical leadership, and compliance, whereas SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) emphasizes participatory decision-making. Studies show that ESG frameworks and ethical leadership increase sustainability, workplace justice, and long-term organizational resilience.

5.1. Implication of Study

5.1.1. Social Implication

Research shows that ethical leadership and ESG policies build a socially responsible firm. Positive employee well-being, diversity, and community participation help firms adhere to SDGs 8 and 10, including decent employment, economic growth, and eliminating disparities. Embracing sustainability may enhance societal well-being and increase employee satisfaction inside firms.

5.1.2. Practical Implications

Managers and policymakers can apply these principles to create ESG-focused policies that meet company and stakeholder goals. Trust and accountability from ethical leadership promote employee loyalty and retention. Regular audits and stakeholder engagement in decision-making enhance organizational openness and investor trust.

5.1.3. Managerial Implications

Managers and policymakers may utilize these concepts to design ESG-focused policies that comply with corporate goals and stakeholder expectations. Ethical leadership fosters trust and responsibility, which boosts employee loyalty and retention. Regular audits and stakeholder involvement in decision-making promote transparency and investor confidence in the organization.

6. Conclusions

This study illustrates how ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) policies and ethical leadership promote employee happiness, diversity and inclusion, community participation, and organizational training and growth. The results show that effective governance and ethical leadership are essential for openness, accountability, and sustainable business. Investment in renewable energy and resource conservation illustrate how important sustainability is for companies. Social initiatives like inclusion and well-being boost employee motivation and commitment. Positive performance, workplace culture, and social responsibility are all influenced by ethical leadership.

Additionally, the study also emphasizes several aspects of the United Nation SDGs. The study indicates that ESG practices are interrelated, and ethical leadership plays a vital role in developing sustainability in the firm. The firm’s practices align with several SDGs, which are as follows: employee well-being, training and development, and diversity and inclusion, SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 5 (Gender Equality) are promoted; SDG 8 and inclusive policies benefit from ESG-driven workplace improvements; Community engagement promotes SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities); and ethical leadership promotes SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) through transparency. The findings suggest that ESG and ethical leadership are essential to sustainability and social responsibility.

In terms of contributions, this research advances the understanding of how ESG frameworks impact social sustainability outcomes, bridging gaps in prior literature. Additionally, it provides empirical evidence supporting the integration of ESG practices with ethical leadership for enhancing employee well-being, diversity, community engagement, and training and development.

However, this study has certain limitations. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases, and the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality. Future research should consider longitudinal studies and expand the scope to different organizational contexts to validate and generalize these findings.

The implications of this study are relevant for policymakers, business leaders, and sustainability advocates. Organizations should embed ESG principles into their corporate strategies to cultivate an inclusive and sustainable work environment. Additionally, ethical leadership training should be prioritized to enhance the effectiveness of ESG initiatives. Policymakers should develop regulatory frameworks that encourage businesses to adopt ESG-aligned practices, ultimately contributing to broader sustainability goals.

Future Direction of Work

ESG practices’ long-term implications on organizational performance and employee well-being may be studied for sustainability. Exploring sector-specific ESG implementation can also illuminate industry best practices. Further research should study how digital transformation and technology-driven sustainability activities moderate and improve ESG effectiveness. Adding varied cultural and geographical settings to the research would improve generalizability and help explain ESG dynamics in global corporate environments.