1. Introduction

During the 20th century, urban planning was drastically transformed, significantly influenced by the development of the automobile industry. This led to automobile-centric urban planning, where city plans were primarily based on roads and traffic [

1]. As a result, previously integrated urban spaces were disintegrated, resulting in social exclusion in cities [

2]. However, during the 1960s and 1970s, urban theorists and academics such as J. Gehl, Jacobs, Whyte, Appleyard, Rapoport, and others began advocating a shift in focus. They emphasized the importance of human experience in urban spaces, with human-scale design principles as a counter to prevailing functionalist, car-centric tactics. Their “cities for people” philosophy caught on and was widely used, particularly in the United States and Europe, during the late 1960s and through the 1990s [

3,

4]. Since the early 2000s, research in human-centered urban planning has included increasingly sophisticated and nuanced factors. Besides planning the public spaces where people are to come together, socialize, and participate in leisure activities, researchers today are emphasizing the importance of democratic values in designing public urban spaces. Researchers argue that their accessibility and utilization should be made inclusive enough to enable equal opportunities for all, irrespective of age, gender, economic status, religion, or any other distinguishing traits [

5]. Today, the concept of re-humanizing cities is gaining momentum throughout the world and is becoming a normal course of action in city planning globally [

1].

Although the cultural, social, and spatial composition of cities differs globally, public urban spaces are essential to the daily activities of urban residents [

6]. Urban areas are places where individuals engage in a variety of activities, socialize with peers, and interact with others. Consequently, public urban space is a factor promoting social sustainability and the enhancement of safety, livability, and vitality. Consequently, spatial configurations that foster social cohesion are regarded as critical indicators of the character of urban spaces [

7]. Therefore, public urban spaces that are friendly to humans are those spaces that are livable, walkable, safe, enjoyable, and inclusive. These spaces offer lively social interaction where people visit to be entertained, socialize with friends, and engage with the wider society [

8].

As a result, experts such as planners, architects, landscape architects, urban sociologists, and urban designers have been undertaking studies to better understand the design and provision of urban space based on people’s needs [

2]. Public parks are natural buffers that help to sustain the urban environment by improving the quality of life for city residents while also providing visual benefits. Parks can improve the socio-economic situation of metropolitan residents while also improving the physical environment [

9]. As a result, urban green spaces are increasingly being acknowledged as a critical component in satisfying the needs of a sustainable and healthy urban society.

Urban parks have been recognized for the social functions they serve, such as meeting places and areas for entertainment, recreation, and relaxation, and their amenity values, which include contributions to aesthetic enjoyment, quality of life, security, and freedom from urban noise and pollution [

10]. Improving ambient environmental quality, increasing opportunities for healthy lifestyles, and allowing people to interact with nature are three ways in which urban green spaces can promote community health and well-being [

4].

2. Literature Review

The problems resulting from the industrialization of metropolises and the after-effects of urban development have made it necessary to protect the important elements that contribute to the development of human society through enhancing socio-economic conditions and offering convenient urban environments such as parks and green spaces. Urban and human sustainable development provides a foundation for ecological growth and the coexistence of humans and the natural world [

11].

Urban public spaces facilitate social interactions among inhabitants, serving as essential elements for enhancing integration, fostering social activities, and developing interpersonal relationships. The quality and extent of social interactions among people might be seen as a component of social sustainability. The environmental conditions of public spaces can significantly influence their attractiveness to various audiences and the nature and magnitude of their attendance. In other words, good environmental conditions are efficacious in facilitating those social interactions that can be examined in the domains of activity and physicality.

Social sustainability is a significant component of sustainable development, which has garnered substantial attention in various countries in recent years. The functions of sustainable development in the social environment have been established through the consideration of principles such as social justice, impartiality, and social welfare. Scholars have highlighted key components of social sustainability, including social justice, social solidarity, participation, and security. Furthermore, components such as equal opportunities, collective progress, equitable social roles, and the security and safety of human settlements against natural hazards serve as the foundation for assessing social sustainability [

12]. Essential urban sustainability theories, such as Gehl’s “Cities for People”, concentrate on re-orienting city planning toward the pedestrian and cyclist, therefore enhancing the quality of urban living. The public spaces in a given urban area should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their traits and advantages, being open for a range of events and possibilities [

13].

Jan Gehl’s original approach is predicated on the idea that, in the course of city design, people are the most crucial concern of public space. The design and development of spaces are guided by the goals of public life, aimed at supporting certain intended activities. As part of this vision, spaces can be developed based on the specifications of the intended path, destination, user groups, and events. The area should be designed to maximize its current values and produce fresh ones. The answer begins with the design of the vision and an extensive program of events, depending on the kind of living activities and attractions that a region naturally offers.

Developing a network of public spaces that can support the concept of public life with respect to the circumstances, form, and climate of the region is the next challenge. The fundamental point is that the quality of life in urban environments depends significantly on the usage of public space. While typically based on traffic and buildings, the conventional approach of planning must be reversed to take people and users into greater consideration throughout the planning process. The classical strategy leaves most of the crucial elements needed to make the city lively, safe, and appealing to chance. Applying the Gehl approach helps us to build a distinct route of thinking: people first and then the surroundings, in a manner that is catered to their needs [

14].

Urban green spaces and open areas are the natural survivors of cities that have undergone quantitative and qualitative changes due to unregulated urban development, resulting in numerous ecological, social, and economic effects [

10]. Public spaces improve the physical and mental health of inhabitants through the provision of clean green areas, sidewalks, and bike lanes, encouraging outdoor activities. Furthermore, public parks and other green spaces can help a great deal in terms of both coping with and reducing the effects of climate change [

2]. They offer the best and most efficient means of enhancing the microclimate, especially through mitigating the impact of the urban heat island (UHI) effect. Public spaces are extensively recognized in international agendas and can assist cities in achieving the objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” [

15].

Urban parks are considered a crucial component of urban and community development, serving a purpose beyond mere recreational activities. Research has indicated that the built environment has the capacity to both facilitate and restrict engagement in physical activities [

11]. Access to green spaces in cities is crucial in supporting urban social and ecological systems. To endorse the many functions of green spaces, it is necessary to take into account a specific degree of qualitative advancement and the equitable distribution of green spaces in metropolitan areas, as outlined in the environmental sustainability agenda [

16,

17]. Urban parks play socio-economic and ecological roles, providing advantages such as contributing to the treatment of mental illnesses, providing a favorable environment for raising children, and social integration. They provide a certain level of comfort, an indicator of social development. Therefore, through careful planning, urban parks can improve both mental and physical health [

15]. Researchers have shown that green areas may have a calming effect, restore energy, and even lower the likelihood of violent incidents. The urban environment may offer economic benefits to both managers and citizens, in addition to socio-physiological advantages. One possible outcome of tree-based air purification is a decrease in the overall cost of pollution mitigation. Additionally, urban parks can boost the attractiveness, tourism value, and income of cities due to their historical, aesthetic, and recreational benefits [

18].

The recreational options offered by urban parks and green spaces are invaluable to city dwellers. To combat social exclusion, strengthen communities through shared spaces, find solutions to societal issues, and promote physical and mental well-being, parks and green spaces offer a variety of uses, including athletics, relaxation, and health promotion. Urban green spaces offer significant potential for enhancing quality of life, enabling individuals to attain health advantages [

16]. Exponential urbanization poses a significant threat to the long-term viability of cities and the overall well-being of their inhabitants. Studies have shown that green spaces and parks in cities are a great way to improve the social lives of residents. When it comes to urban social and ecological processes, green spaces are crucial. Citizens possess diverse perspectives toward urban green spaces, resulting in varying interpretations based on their distinct requirements [

19].

3. Humanizing Public Spaces and Quality of Life in KSA

3.1. Quality of Life Program in KSA

The Council of Economic and Development Affairs has created an integrated governance system to guarantee efficient stakeholder involvement in accordance with the Council of Ministers’ directions to create the framework and resources required to achieve Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. As a result, several Vision Realization Programs (VRPs), such as the Quality of Life Program, have been introduced to continuously support the process of transforming the economy from one that relies on income to one that is productive and competitive on a global scale. The Quality of Life Program was introduced in 2018 with the primary goal of improving people’s lives by creating the conditions needed to develop more important options that increase the involvement and inclusion of both locals and foreigners in their cultural, athletic, and entertainment pursuits [

20].

In order to increase the Quality of Life Program’s direct involvement in the development of livability in Saudi cities, it was decided to assign additional strategic goals based on an evaluation of the previous phase’s deliverables, feedback from stakeholders regarding the quality of life sectors, and a revision of the next phase’s priorities. As a result, the Program’s strategic priorities and execution plan have been revised to consider the leadership’s new outlook, in alignment with the updated Vision 2030 [

21].

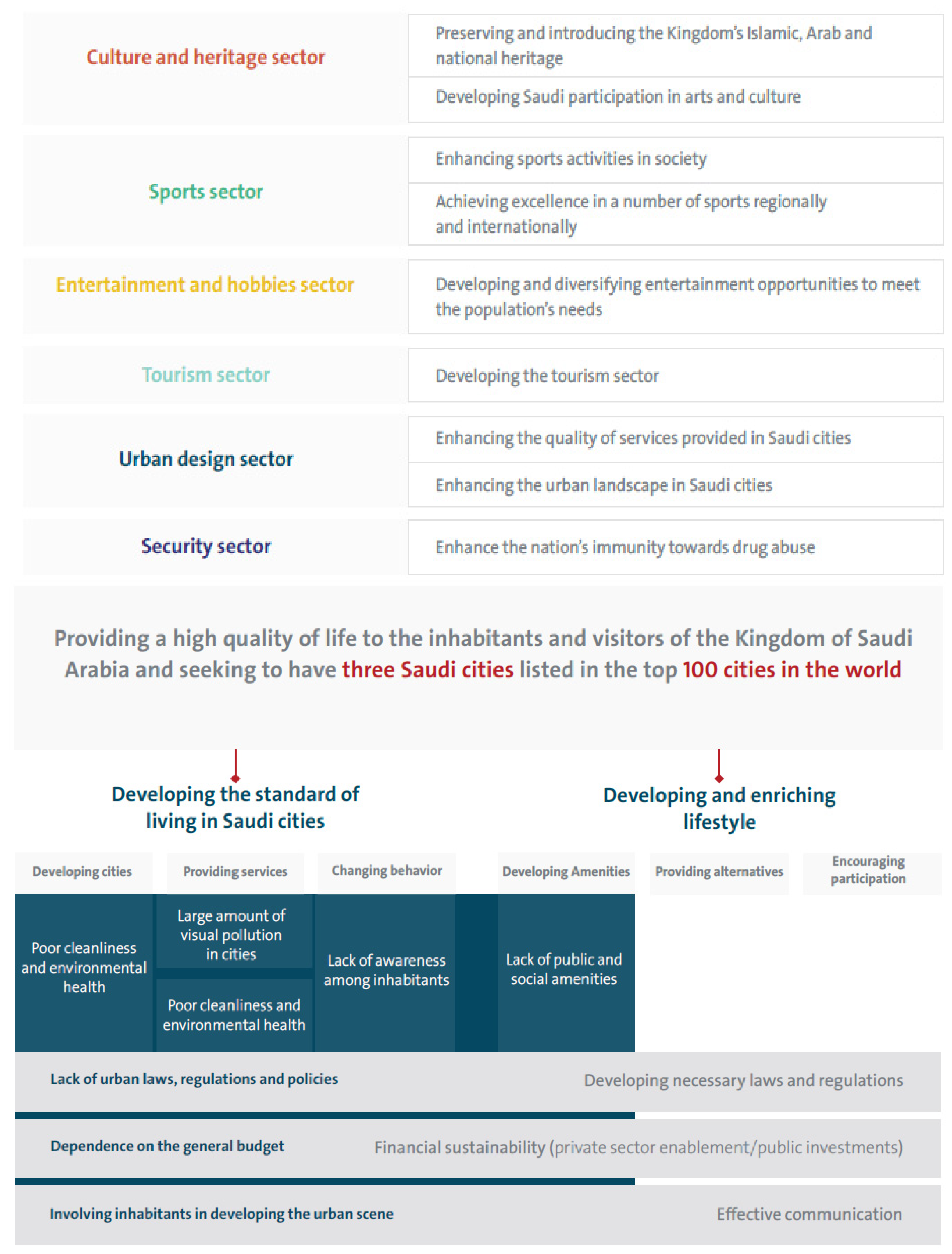

The Program’s strategic goals, which were influenced by Vision 2030, were connected to the pertinent sectors that the Program seeks to empower in order to obtain a thorough understanding of its scope. These sectors are detailed in

Figure 1.

3.2. Humanization of Cities Initiative

To create communities that are safe and healthy for all residents, the Humanization of Communities Initiative is working to change the paradigm of urban development from one that prioritizes cars to one that prioritizes people. The initiative aims to transform cities so that they are more accommodating to people and the environment [

11].

In partnership with the Ministry of Municipal Rural Affairs and Housing, the Program is working on humanizing cities through the construction of more open areas, playgrounds, parks, plazas, and plazas; a network of pedestrian pathways; recreational sites for celebrations and festivals; entrance decorations; and visually appealing landmarks to increase the amount of public space that everyone can enjoy [

20].

The project has already helped to increase the quantity of open green space in Saudi cities, making them more human-friendly and helping residents to feel more at ease. With the help of this program, the Ministry of Municipal Rural Affairs and Housing has planted 23.46 million trees and established 217 parks, 50 squares, and 254 playgrounds that are suitable for children [

20,

21].

4. Urban Humanization Indicators

4.1. Security

The concept of security in relation to public spaces can have different meanings, from the street security of the pedestrian concerning vehicular traffic to a sense of protection against violence or anti-social behaviors, which can often occur in highly urbanized places [

22].

The security of pedestrians relies on the organization of the sidewalk, the careful separation between pedestrian and vehicle-accessible fluxes, and, finally, on the crossing intersections, where there is the danger of colliding with cars.

According to many studies in the sector of environmental psychology, it can be stated that the feeling of insecurity in relation to illegal behaviors or violent acts in open urban spaces is extremely affected by the urban environment and the architectural features of such urban spaces [

23].

The Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design association suggests planning criteria that could improve the security perception of urban residents. In particular, it claims four fundamental strategies for urban design [

22]:

− Territoriality, intended as a social and belonging identity related to a place.

− Natural surveillance.

− Access control.

− The use and maintenance of the space.

4.2. Environmental Comfort

The perception of well-being in an urban environment associated with environmental factors depends on the air quality and thermo-hygrometric factors linked to micro-climatic conditions. Urban comfort is also related to the existence of furniture and tools that make the urban space easily accessible and usable for all residents, better known as universal design.

The main problems perceived by the people within an urban context concern the following:

− Air pollution;

− Noise;

− Urban traffic;

− Overcrowding;

− Temperature changes.

In the field of environmental psychology, these external factors are classified as environmental stressors linked to the model of living in contemporary cities [

15].

4.3. Psycho-Physical Well-Being Due to the Presence of Greenery

The perception of psycho-physical well-being also relates to ecological factors, such as the existence of greenery and open spaces, which influence—according to different studies—the quality of life and health of urban inhabitants. Trees and green areas located in a city not only improve the quality of the urban environment, thus reducing environmental tensions (air quality, noise, traffic, overcrowding), but also motivate people to carry out more physical activities, with positive effects on their health [

24]. Those who live closer to a public park may encounter fewer risks, such as contracting obesity-related diseases associated with a sedentary life.

4.4. Psychological Comfort Due to Cognitive Factors

The perception of psychological comfort within an open urban space is linked with the legibility and shape of the space, which favor orientation and give a sense of security to those who are walking in the street, enabling the capacity to understand a place as a factor that drives one’s own choices. Kevin Lynch’s book

The Image of the City, published in 1960, introduced a new concept of the city, beginning with the perception of the city from its inhabitants, including studies that lead to a deeper understanding of the issues related to wayfinding and orientation [

25].

4.5. Accessibility and Universal Design

The accessibility and usability of a place require all barriers to be removed, as they generate inconvenience, risk, fatigue, stress, and so on, especially for less-advantaged users, such as those who are disabled or older and children [

26]. The universal design concept includes the idea of comfort and security of any pedestrian (as mentioned above) and surpasses the traditional and reductive approach of overcoming physical obstacles with just a ramp—in relation to the concept of a disabled person in a wheelchair. An urban space that is accessible to everyone is a place where both children and older people with handicaps (motoric, sensitive, cognitive) can move independently and safely; where they can find somewhere to pause and rest, find a fountain to drink some water, or access hygienic services; where there are usable and equipped areas, paths with adequate slopes, easily readable signage; and so on [

27]. It is simple to state that a public space should facilitate the movement, for example, of blind or older people with cognitive deficits; however, the issue is far bigger and assumes a specific dissertation that is suitable for discussion of the argument [

27].

4.6. Quality and Maintenance Condition of the Materials

The quality of the materials and their maintenance conditions, in addition to the cleaning and management of the public space, reflect the care of the administration and the citizens responsible for that place. The negligence and decay of a public space, on the other hand, creates a negative perception, which can lead to a sense of insecurity and embarrassment [

28].

4.7. Elements and Place Identity

Psychological well-being is also connected to the cultural and identity elements of a place, to its memory, and even to emotional and sentimental factors.

Models (i.e., preconceptions) condition an individual’s aesthetic evaluation and expression of preferences for a place, which can involve cultural and social aspects that are shared by the whole community. On the contrary, the globalization of languages and competition can bring about the creation of places with astonishing qualities and universally accepted features, which can serve as the objects of visual consumption, thus tending to impoverish the experience of public life, diminishing the identity of a place [

29].

4.8. Attractiveness and Opportunities of the Public Realm

The pleasantness of a place is related to attractive factors, such as the vitality of a place and the presence of people joining the public life and entertaining activities or, instead, elements such as the quietness and amenities of public parks and natural sites.

The liveliness and pleasantness of a public space are affected by the relationships between different elements. The concept of attraction goes beyond sustainability and includes subjective judgments, such as those regarding beauty, that do not suitably match the intrinsic traits of urban spaces [

30]. A place can be attractive and can provoke many emotional sensations—either pleasant or repulsive ones—depending on the past and perceptual experiences of a subject: it can be sufficient to consider just the affective bond that links people to their place of origin.

Generally, the attractiveness of a place relates to the opportunities that it offers to its users, the existence of public services, and the ability to enjoy some free time and meet up with other people, establishing relationships and sharing occasions with them [

31].

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Data Collection Methods

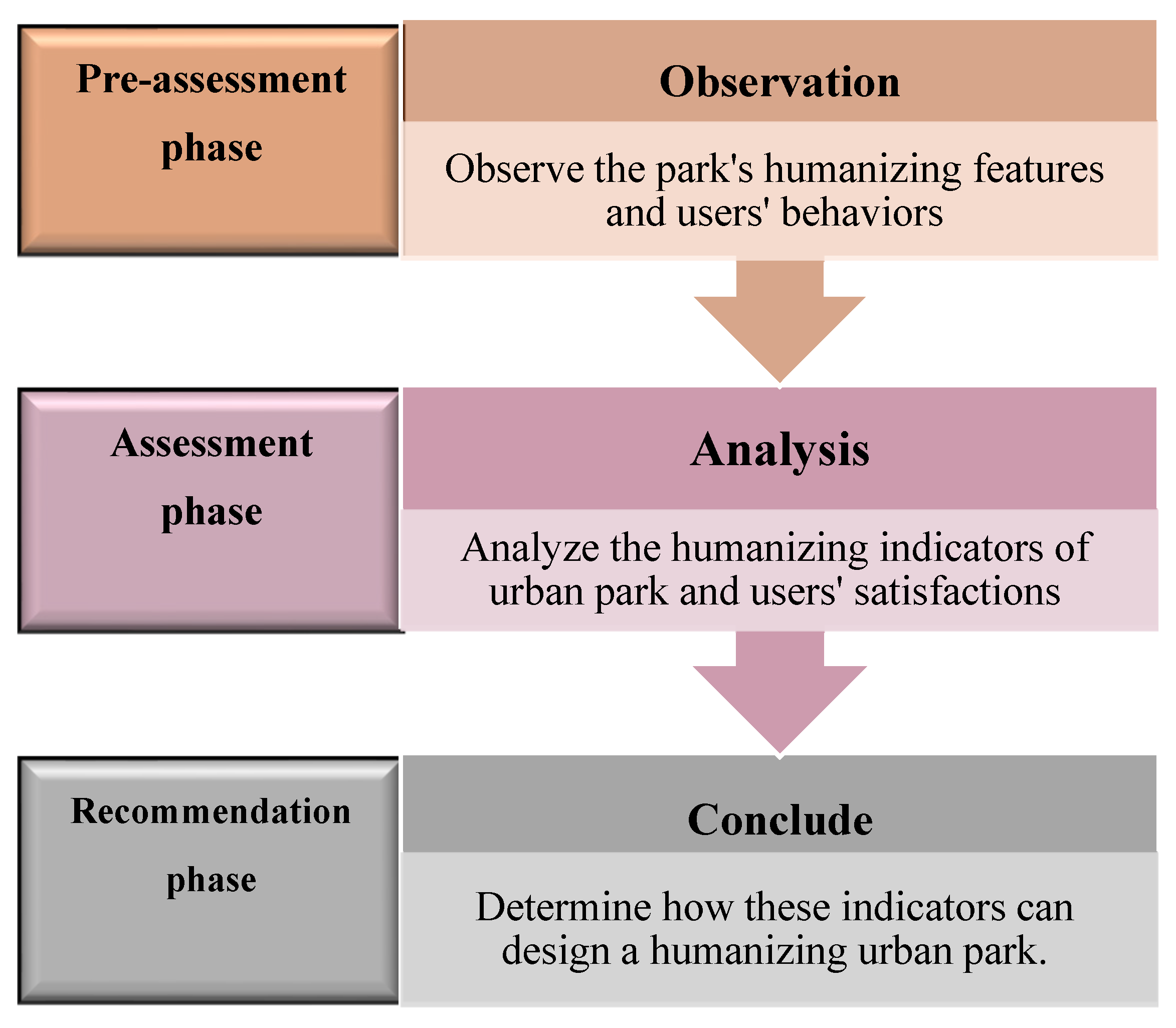

The case study assessment involved three phases. First, in the pre-assessment phase, the park’s humanizing features and user behaviors were observed through visual observation, photography, and videography. Second, in the assessment phase, the humanizing indicators of the case study and users’ satisfaction were analyzed through a questionnaire. After evaluating the current state, the third phase involved suggesting some recommendations for improvement.

Figure 2 provides a detailed explanation of the procedure employed in this research.

5.2. Sampling

This study used simple random sampling to achieve an equal selection probability for all participants. Participant selection was bias-free, avoiding demographic segmentation.

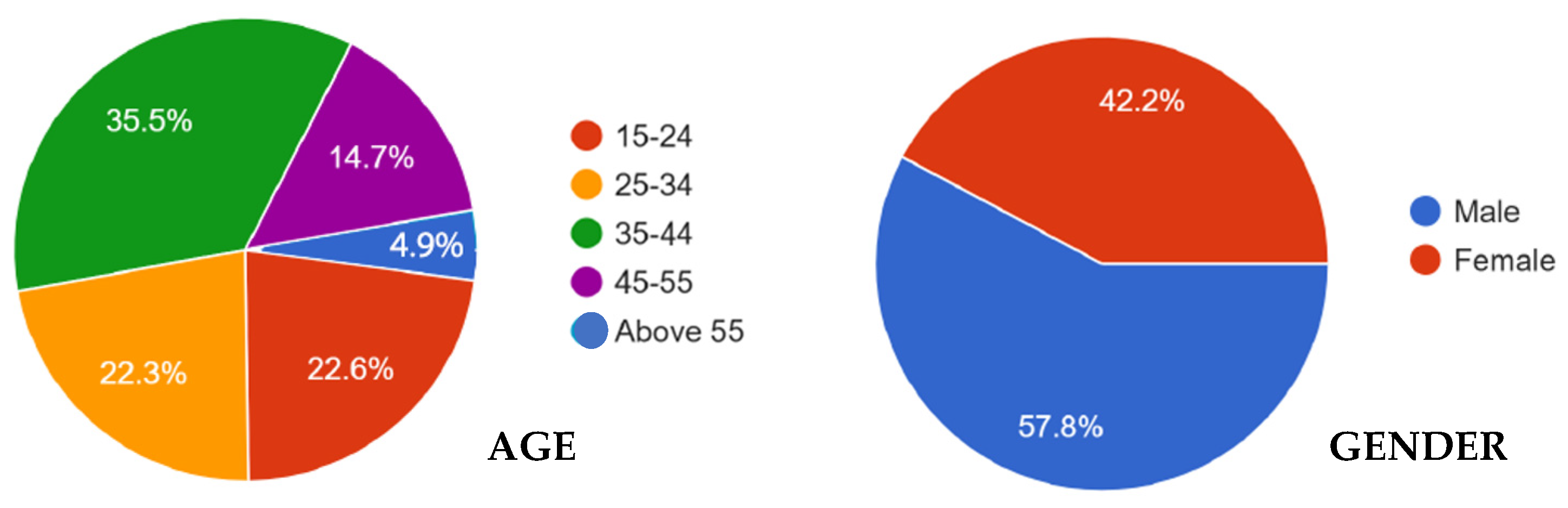

A questionnaire for the assessment phase was distributed to park visitors over different days and times and reached 350 respondents; see

Figure 3 for their demographics. The sample was diverse in terms of gender and age, which facilitated the collection of different perspectives.

6. Pre-Assessment Phase

6.1. Prince Majid Park, Jeddah

Jeddah has a multitude of entertainment options. The city is well known for both its historical landmarks and its array of leisure pursuits. As part of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 objective to humanize cities and improve quality of life, Jeddah Municipality has developed public open spaces, including gardens, walkways, and parks. Prince Majid Park is the largest park in Jeddah. The aim of this project is to increase the per capita share of green areas and raise the level of physical activity, with the site containing walkways in addition to Jeddah’s largest open children’s play area spread over 9730 square meters; furthermore, it is supported by various public utilities and provides a safe and attractive recreational environment.

Prince Majid Park is located in the center of Jeddah, spanning 132,000 square meters. It is an ideal destination for family outings, as it provides a range of entertaining activities, from kid-friendly play areas to fountain displays. The park consists of green areas (covering 34% of the total area), with grass cover and natural trees (including 918 trees and 382 palm trees), in addition to shrubs, soil covers, and cacti; see

Figure 4.

6.2. General Information for Prince Majid Park

Location: The park is situated on Makrona Road in front of Al-Handasa Square, Rabwah, Jeddah 23446, Saudi Arabia; see

Figure 5.

Owner: Government of Jeddah.

Inauguration of the project: Jeddah Season festival, May 2022.

Entry fee: Entry to the park is free of charge.

Open hours: The park is open to the public at all hours.

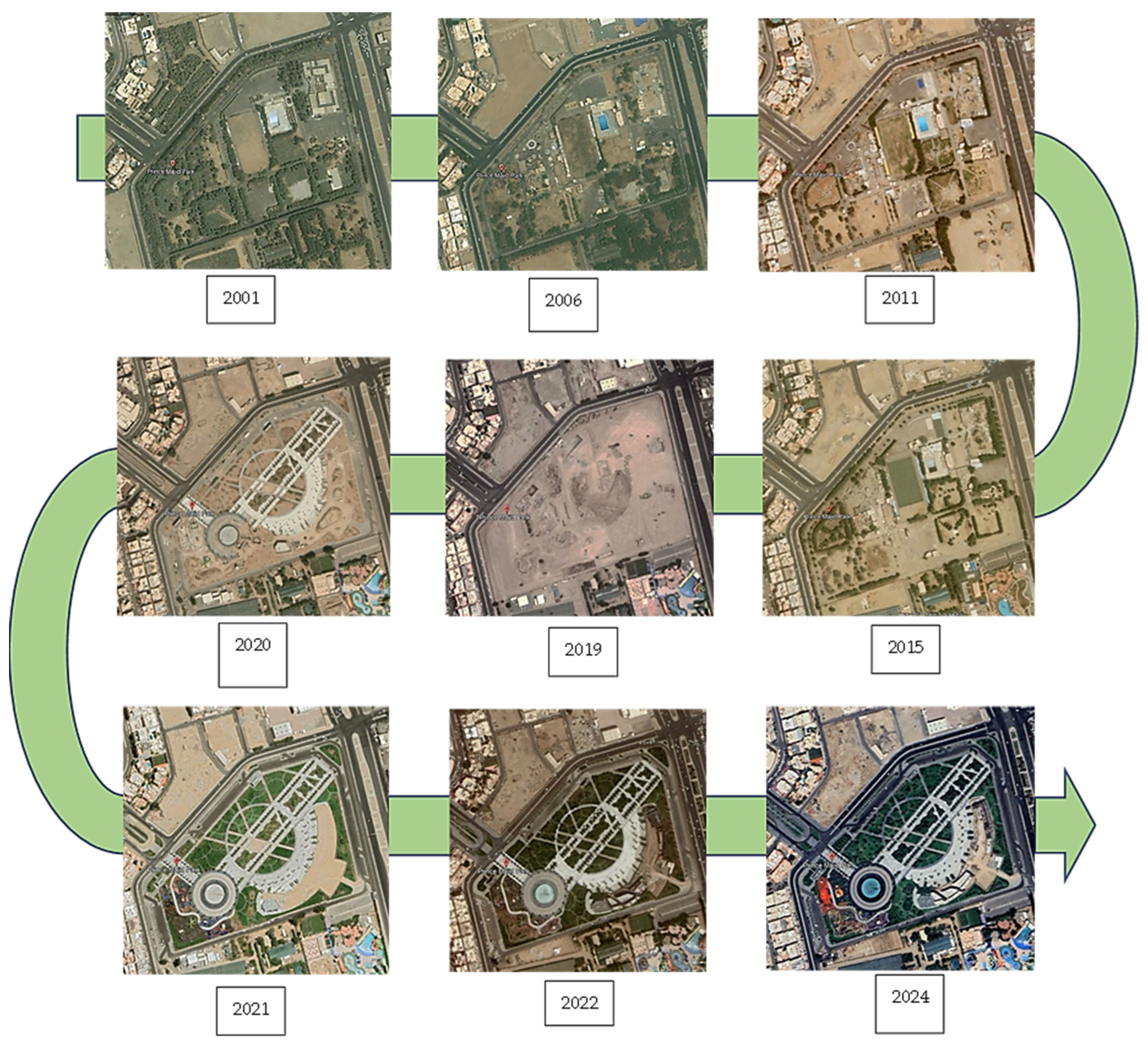

6.3. Historical Images of Prince Majid Park

The following figure shows the historical development of Prince Majid Park (

Figure 6).

6.4. Humanizing Prince Majid Park

Humanizing public spaces such as Prince Majid Park can significantly enhance the quality of life for residents and visitors alike. Some ways in which this goal can be achieved are detailed in the following.

6.4.1. Greenery and Landscaping

Introducing lush greenery, trees, and well-maintained landscaping can create a more inviting and tranquil environment. This not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of the space but also contributes to cleaner air and a cooler microclimate.

Figure 7 shows the greenery in Prince Majid Park.

6.4.2. Recreational Facilities

Incorporating various recreational facilities, such as playgrounds, walking/jogging paths, sports courts, and picnic areas, encourages physical activity and social interactions among individuals of all ages. Playgrounds inside the park are developed especially for children, which include several types of swings and slides. In addition, playing various games at the park helps parents and children form stronger bonds. These facilities promote a healthier lifestyle and foster community engagement.

Figure 8 depicts some of the recreational activities in Prince Majid Park.

6.4.3. Seating and Gathering Spaces

Providing ample seating options, such as benches, shaded areas, and outdoor seating arrangements, encourages people to linger, socialize, and enjoy their surroundings. Well-designed gathering spaces can facilitate spontaneous interactions and strengthen social bonds within the community.

Figure 9 shows some gathering spaces in Prince Majid Park.

6.4.4. Art and Culture

Integrating art installations, sculptures, murals, and cultural elements add vibrancy and character to parks. In Prince Majid Park, there are numerous small cottages lining the streets that are set aside for artists to showcase their talents and original creations. Artistic expressions serve as focal points for exploration and contemplation, enriching the overall experience and fostering a sense of identity and pride among residents.

Figure 10 shows the artistic features and cultural activities in the park.

6.4.5. Accessibility and Inclusivity

Ensuring accessibility for individuals with disabilities, including wheelchair ramps, tactile paving, and designated parking spaces, promotes inclusivity and allows people of all ability levels to fully enjoy the park. Additionally, providing amenities such as clean restrooms and drinking fountains enhances the comfort and convenience for visitors.

Figure 11 depicts some of the accessibility features of Prince Majid Park.

6.4.6. Events and Programming

Hosting events, festivals, and educational programs within the park creates opportunities for cultural exchanges, learning, and entertainment. Cultural performances serve as a means of gaining knowledge and obtaining insight into the cultures of other nations.

These activities attract diverse audiences and contribute to a dynamic and lively atmosphere, further strengthening community cohesion; see

Figure 12.

6.4.7. Safety and Security

Implementing appropriate lighting, surveillance systems, and visible security patrols helps to ensure the safety and well-being of park users. Creating a sense of security encourages people to visit the park regularly and feel comfortable while spending time outdoors.

Figure 13 shows some of the safety and security amenities of Prince Majid Park.

6.4.8. Environmental Sustainability

Incorporating sustainable design features, such as rainwater harvesting systems, solar-powered lighting, and native plant landscaping, promotes environmental stewardship and reduces the park’s ecological footprint. These initiatives contribute to the overall resilience and long-term viability of the public space.

Figure 14 shows some of the sustainable design features of Prince Majid Park.

Through prioritizing these aspects, Prince Majid Park has been transformed into a welcoming and inclusive environment that enhances the quality of life of the residents of Jeddah, offering a place for relaxation, recreation, and connection with both nature and the community.

7. Assessment Phase (Humanizing Indicator Analysis for Prince Majid Park)

UN Habitat’s Global Public Space Programme supports local governments in creating and promoting socially inclusive, integrated, connected, and environmentally sustainable public spaces, promoting a better quality of life for all. The Programme has chosen observable and quantifiable indicators that provide useful information on the quality of public spaces and aid in determining performance targets for the future in order to accomplish SDG11.7.

For this study, these indicators were divided into five main categories: green environment, comfort and safety, amenities and furnishings, accessibility, and uses and users. These metrics can aid in transforming a chosen location into a more secure, welcoming, accessible, and environmentally friendly public area.

The community has the chance to participate in the assessment and communicate their wants and spatial perceptions during this phase, allowing for the highest level of user engagement. In order to obtain a quality score for each indicator (ranging from one to five), a questionnaire was issued to park visitors.

In order to establish the findings and emphasize the primary difficulties and opportunities of each dimension, the gathered data were cleaned and examined to provide technical recommendations and solutions for the enhancement of public spaces.

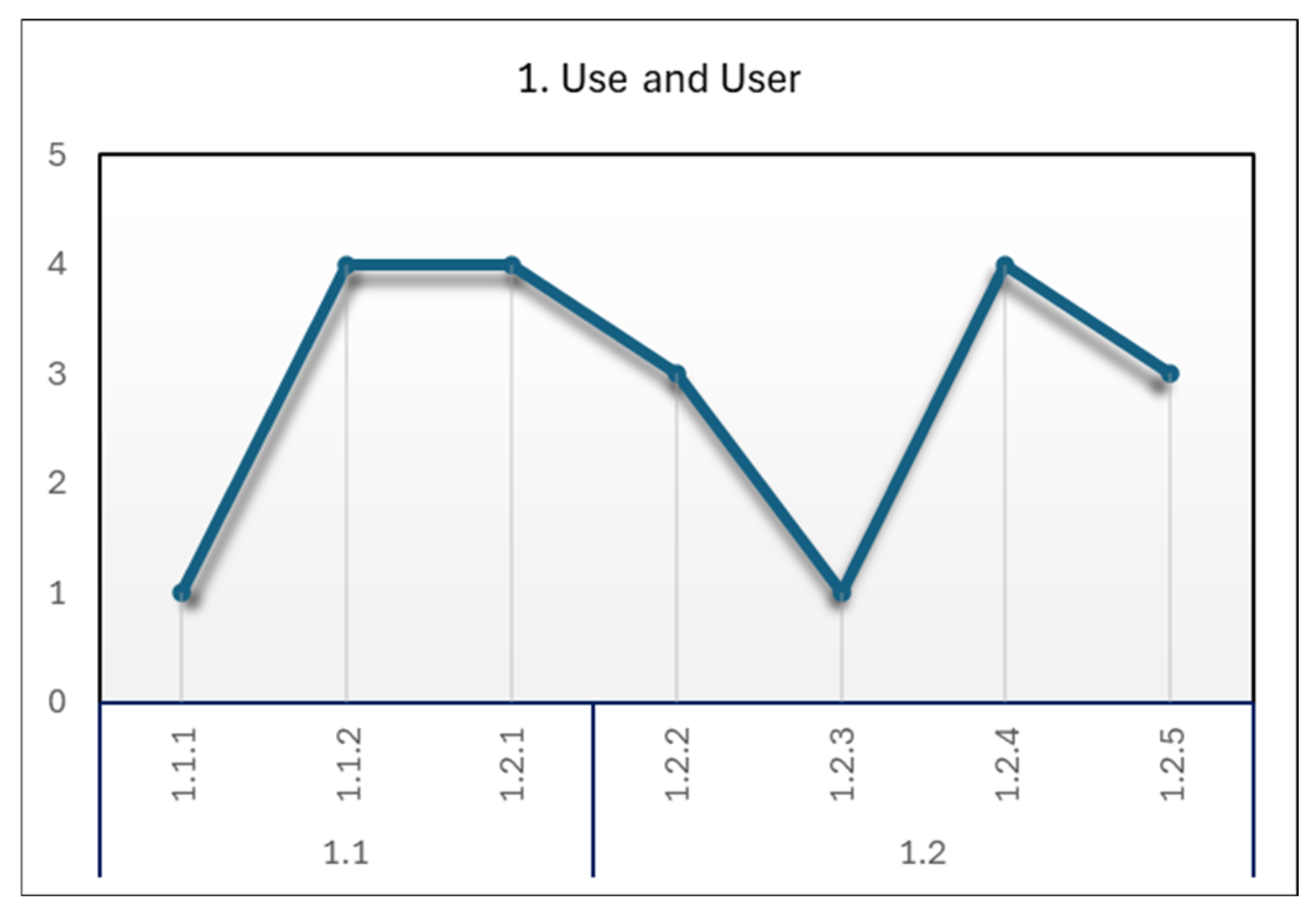

7.1. Uses and Users

This dimension emphasizes the usage of the area and who is using it. A high-quality public place is one that everyone may use, where people from all backgrounds can spend a lot of time appreciating the area, especially the most vulnerable populations. Considering this dimension, one can evaluate the inclusive nature of the space by noting the range of users and the kind of events occurring. See

Table 1.

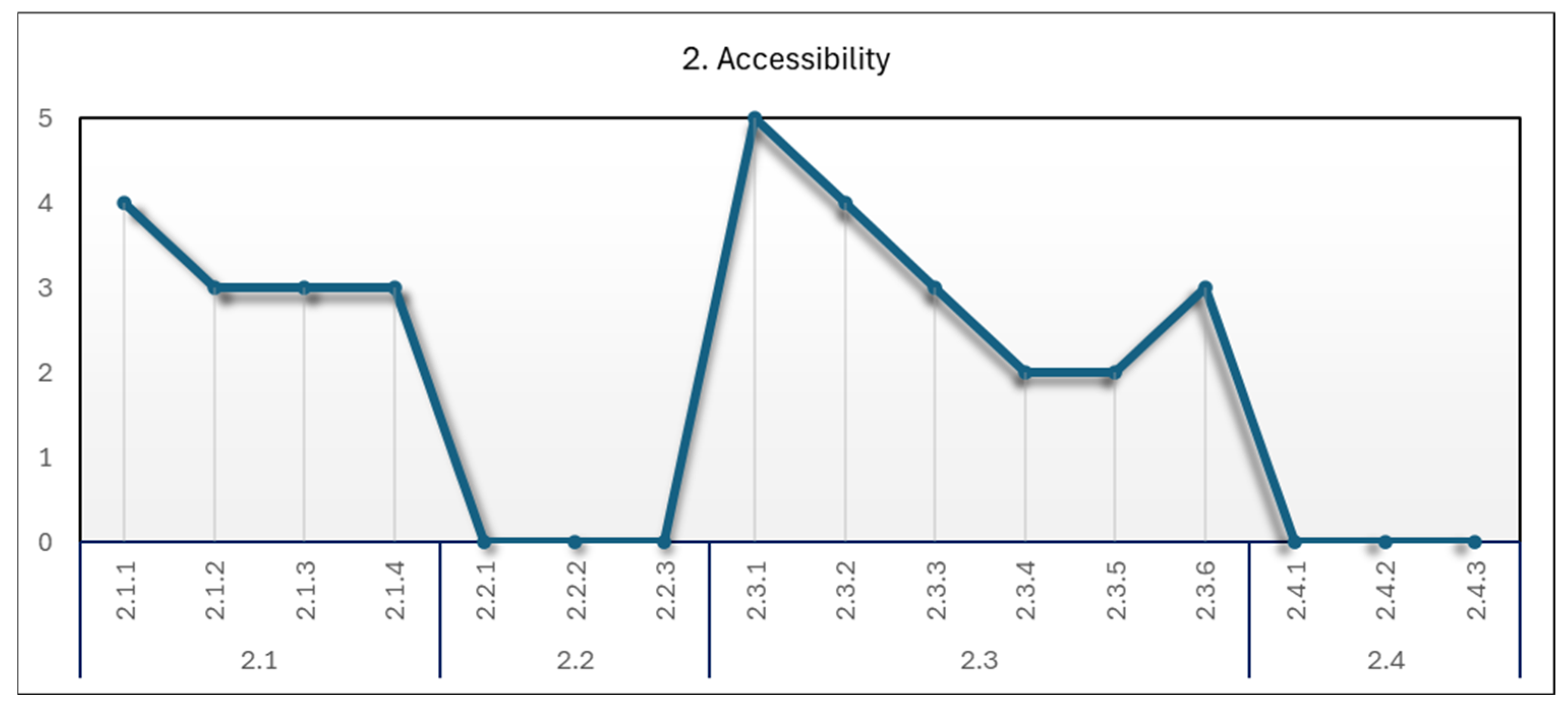

7.2. Accessibility

This dimension concentrates on the physical and perceptual access to the site. Particularly for the elderly and others with special needs, walking, cycling, or public transportation should provide quick access to a public space. The dimension also reflects its limitations of use (operation use) and by-laws, as a public area should be open for all without requiring an admission fee. Finally, one also evaluates accessibility in general, for instance, whether individuals feel welcome and at ease visiting the public area. See

Table 2.

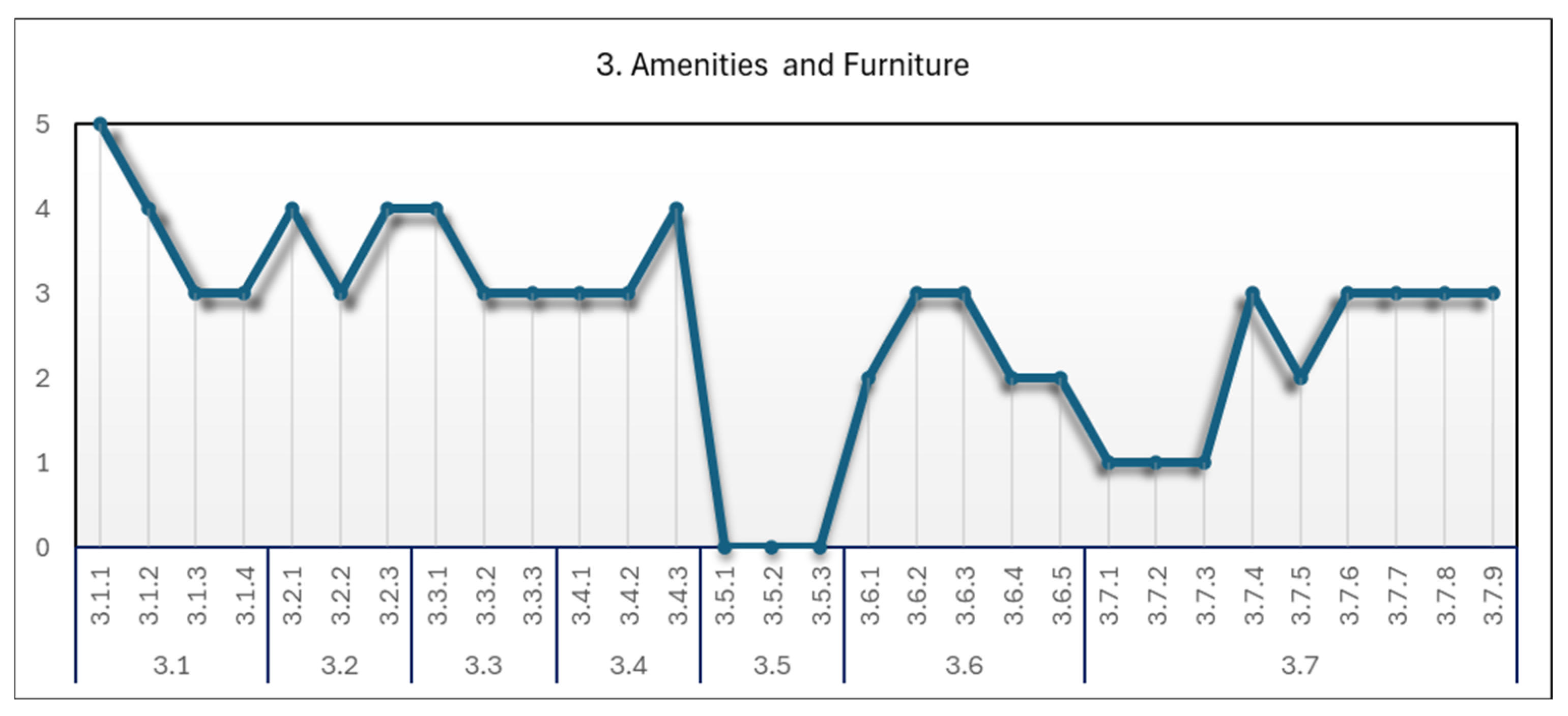

7.3. Amenities and Furniture

Amenities and furnishings enhance the appeal of public areas. This may encompass (but is not restricted to) areas for recreation, relaxation, dining, and hydration, in addition to utilities such as illumination, garbage receptacles, and restrooms, among others. This dimension examines their availability, distribution, and quality/condition. Amenities and furnishings must be inclusive, addressing the requirements of the diverse groups within the community. See

Table 3.

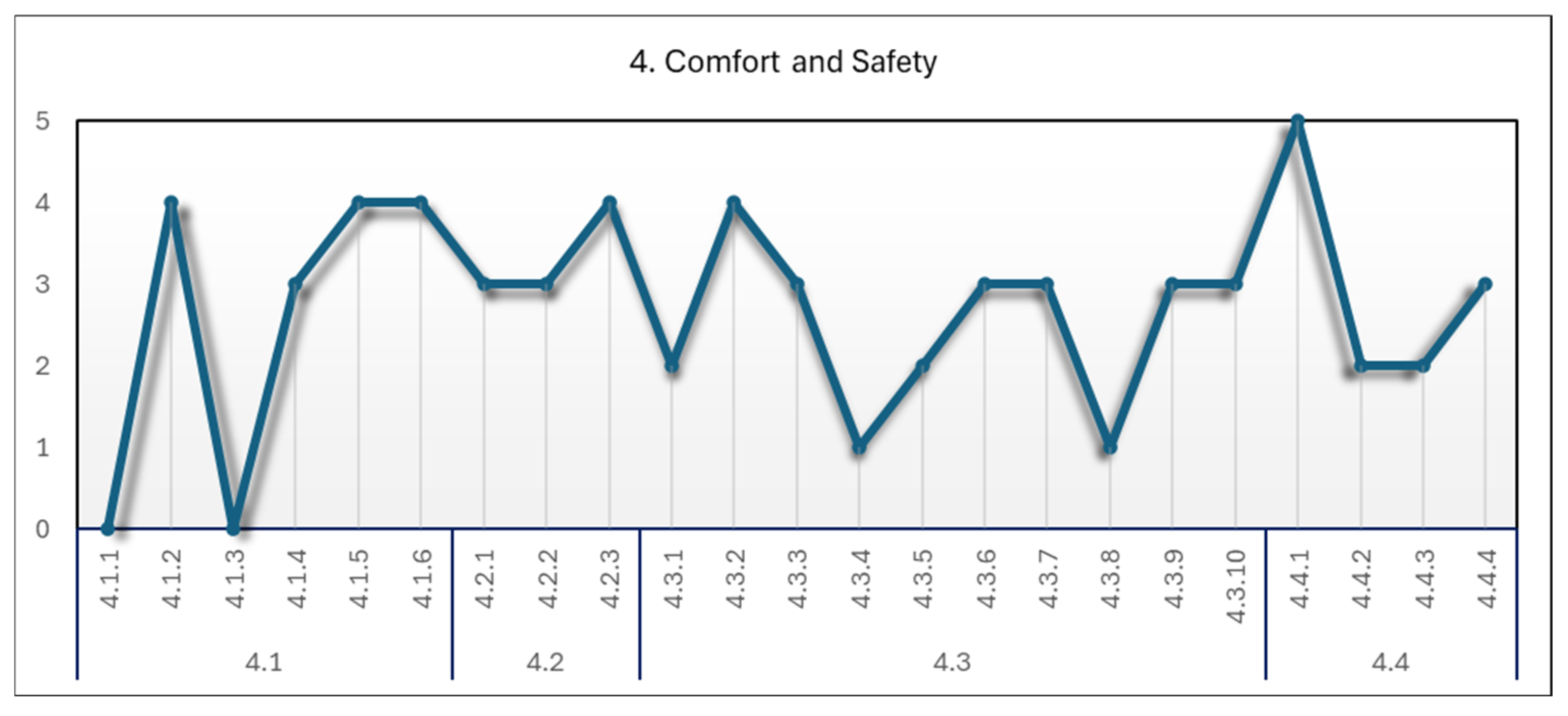

7.4. Comfort and Safety

This component examines people’s impressions and feelings, which can significantly affect their welfare and time spent in a public area. While damaged and poorly cared for locations might have the opposite impact, well-kept areas are usually seen as safe and comforting. Deal-breakers for comfort include the smell, sound, visual and physical condition, and general identity of a venue. While some people may feel comfortable using a location, others would feel threatened by lack of visibility, concentration of particular groups, and/or the absence of activities or historical events. Safety is a personal concept. See

Table 4.

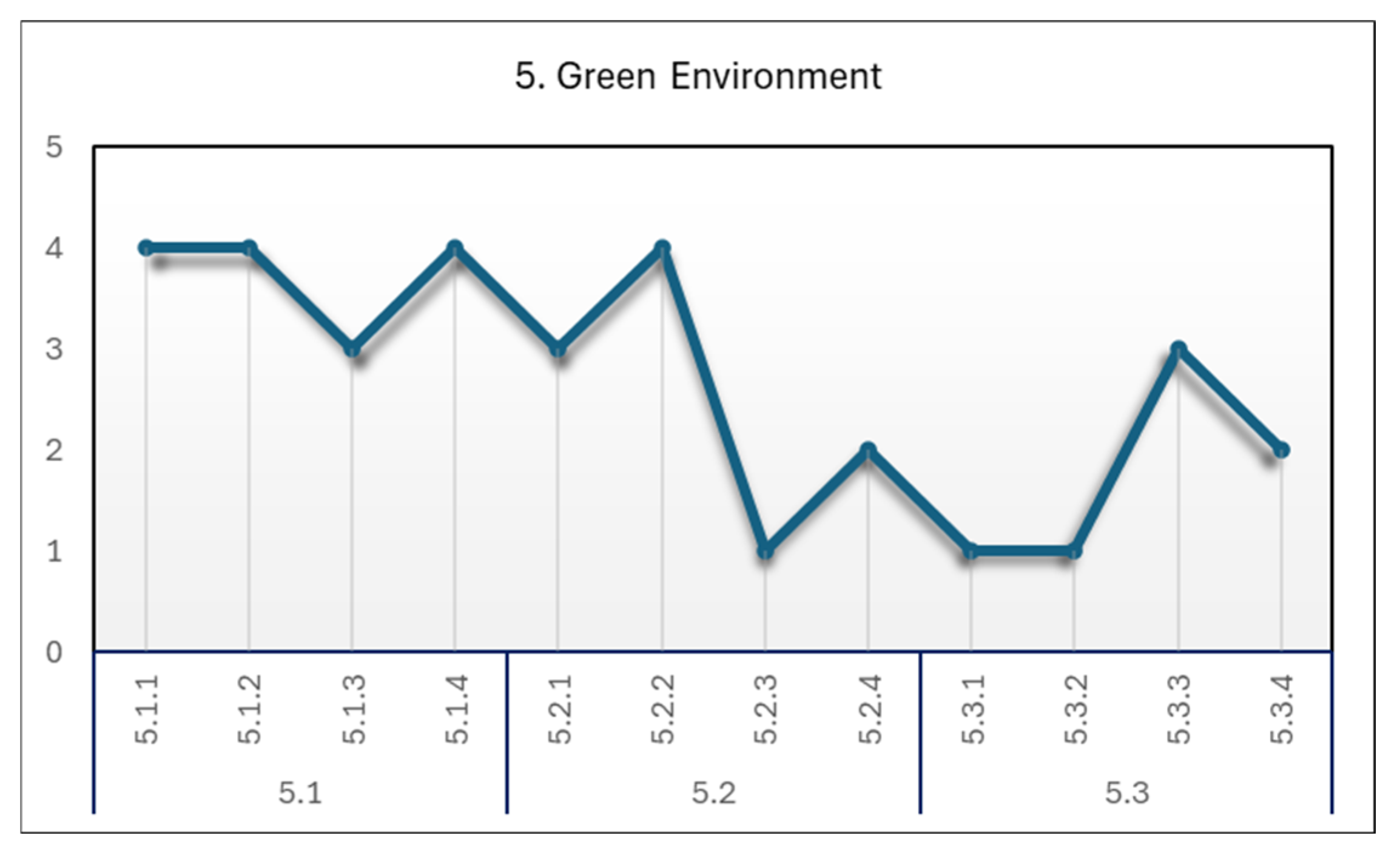

7.5. Green Environment

This dimension addresses environmental elements that could enhance the quality of life of citizens. Green areas have grown increasingly valuable in crowded cities, as they offer harmony between development and nature. Appropriate green covers and water management in well-designed public areas can significantly improve air quality and lower noise levels, control heat and temperature, prevent soil erosion, and support adaptation to and mitigation of the consequences of climate change. Furthermore, trees, grass, and other types of vegetation provide habitats for various animals. See

Table 5.

8. Data Analysis

Based on the assessment for humanizing indicators for Prince Majid Park, the data were analyzed to understand how Prince Majid Park performs and how it can be managed to better achieve the associated goals.

8.1. Uses and Users Indicator Analysis

The park has diverse users present in the area during the night, and there are various inclusive activities in public spaces across time (suitable for children, the elderly, individuals with disabilities, and so on), which enables social interactions. However, more development is needed to attract visitors during the day; see

Figure 15.

8.2. Accessibility Indicator Analysis

The park has a great number of zones designated for pedestrian circulation and a good level of zones designated for private vehicle circulation and other designated areas regarding their dimensions, design, location, and conditions. However, the existence of ramps that are correctly designed for wheelchairs and the presence of tactile pavement paths should be improved. Furthermore, the park is missing designated zones for bicycle lanes and public transportation; see

Figure 16.

8.3. Amenities and Furniture Indicator Analysis

The park has a great level of natural lighting, a good presence of artificial lighting at night, a good level of inclusive recreational facilities for outdoor activities, and a good quantity of main or secondary seating (e.g., stairs, movable chairs, and benches). However, the condition and location of emergency facilities and the availability of public restrooms need to be improved. Furthermore, the quality of bike racks is lacking in terms of their layout, size, and positioning; see

Figure 17.

8.4. Comfort and Safety Indicator Analysis

The park has an excellent reputation in terms of the neighborhood and public area. The community’s perception of the safety level is good all day, with good pleasant views and cleaning service quality in terms of both frequency and outcomes. However, there is a lack of spaces that are protected from the heat and rain (e.g., shades), and its waste management system is also lacking; see

Figure 18.

8.5. Green Environment Indicator Analysis

The green coverage ratio and maintenance conditions of the greenery in the park are very good. Additionally, there are a range of flowers, trees, water bodies, and so on. However, the park should be improved in terms of the presence of environmental risks, the existence of censorial or solar power components (automatic irrigation, social lighting, etc.), and the presence of recyclable waste bins; see

Figure 19.

9. Discussion

The analysis of humanizing indicators for Prince Majid Park allowed for the identification of its advantages and disadvantages regarding its capacity to function as a human-centered public area. In order to improve the user experience, important factors, including community involvement, safety, environmental comfort, accessibility, and facilities, were assessed.

Prince Majid Park’s wide variety of activities, accessible areas, and friendly atmosphere serve as excellent examples of various important facets of urban humanization. Through providing inclusive recreational options for children, families, and senior citizens, the park serves a wide range of users. Social contact has been given top priority in its design, with areas set aside for get-togethers, casual pastimes, and commercial ventures such as food kiosks. Additionally, the park’s function as a gathering place for the community is strengthened by its well-kept vegetation and lively social events, which serve to promote social cohesiveness and raise Jeddah’s standard of living.

The park has parking lots, pedestrian-friendly walkways, and ramps for those with disabilities; however, its complete inclusivity is limited by a lack of bike- and public transportation-related amenities. There is a strong sense of security in the park during the day and early evening thanks to its safety measures, which include surveillance components and lead to a low perception of criminality.

In general, people felt comfortable and protected, especially during the day. This feeling of security could be further increased, though, by installing cameras in less-traveled areas and upgrading the illumination at night.

Despite these advantageous aspects, the park does not possess smart urban sustainability qualities; for example, the analysis drew attention to the lack of rainwater collection equipment, automated irrigation systems, solar-powered lighting, Wi-Fi connectivity, and sensors and monitoring systems. The idea of “smart parks” offers a forward-thinking answer through combining technology with the environment to produce parks that not only provide improved experiences for visitors but also are ecologically sustainable. Advanced technology allows towns to turn conventional parks into smart, interactive, and more readily controlled public areas.

In keeping with international smart city ambitions, integrating this technology can be expected to improve the park’s ecological sustainability, lower operating expenses, and establish it as a progressive public area. Furthermore, although its vegetation is well maintained, there is a conspicuous lack of shade structures, particularly in spots that receive direct morning sunlight. Thus, adding more areas that provide shade can be expected to greatly enhance thermal comfort and promote more park visits during periods of hot weather.

Finally, adding features such as bike racks, more tactile pathways for guests with visual impairments, and more signs would enhance the park’s infrastructure. By improving these elements, the park could become more welcoming, accessible, and comfortable for people of various backgrounds, thus promoting urban humanization.

Collaboration with stakeholders and other sectors can help the park’s interventions to be more effective. Multi-sectoral collaboration (including, for example, environment, transport, health, social affairs, police services, and so on) can help to maximize the benefits of urban green spaces while preventing unintended negative impacts. Furthermore, partnerships with local businesses and organizations can help in funding the establishment of new urban green spaces (especially on private land) and support their maintenance.

In summary, while Prince Majid Park has come a long way in becoming a human-centered urban area, it could become even more of a model public park in the area by addressing the gaps relating to smart, sustainability, and comfort characteristics reported in this study.

10. Conclusions

The process of humanizing public open spaces is an essential component of urban planning that contributes to the enhancement of quality of life, the promotion of social cohesion, and the development of environmentally sustainable practices. Public spaces serve as key infrastructures that encourage leisure activities, cultural engagement, and social connection in Jeddah, which is rapidly becoming an urban environment. The vision of Saudi Arabia places a high priority on sustainable urban development. This is shown by projects such as the Humanization of Cities Initiative and the Quality of Life Program, both of which have the objective of transforming public spaces into urban settings that are resilient, inclusive, and dynamic.

Urban humanization is exemplified by Prince Majid Park, which demonstrates how purposeful design may be used to meet the different requirements of a growing metropolitan population. The park’s incorporation of accessible pathways, vast green areas, varied recreational amenities, and social spaces exemplifies the tenets of inclusive urbanism. The park promotes physical exercise, improves social relationships, and incorporates environmental awareness in its design, thereby satisfying inhabitants’ recreational demands and exemplifying urban ecological sustainability.

Despite its significant achievements, Prince Majid Park has additional potential to enhance its sustainability, inclusivity, and intelligent urban infrastructure. The use of innovative solutions such as smart irrigation systems, renewable energy use, and sophisticated microclimate management strategies—including heat-resistant plants and enhanced shade structures—could substantially enhance the park’s ecological impact. Furthermore, enhancing public transit connectivity, incorporating comprehensive cycling infrastructure, and broadening universally accessible design elements—such as tactile navigation pathways, adaptive signage, and ergonomic seating—would improve the park’s inclusivity for individuals with varying abilities and needs.

In conclusion, Prince Majid Park signifies a substantial advancement in the development of human-centric urban environments in Jeddah. By addressing recognized deficiencies in intelligent, sustainable, and inclusive urban planning, the park could serve as a standard for future public space development in the region. The continuous improvement and research of these urban areas highlight their essential function in promoting resilient, livable, and socially integrated cities. Future research and interdisciplinary collaborations should investigate how emerging technology, ecological techniques, and participatory urban planning models might enhance the concept of humanized public spaces, thereby contributing to the broader discussion on sustainable urbanization.