Abstract

The rural digital governance platform is closely related to rural sustainable development. By playing the role of the rural digital governance platform, it can optimize the allocation of rural resources, improve the efficiency of rural governance, promote the development of rural industries, improve the quality of life of rural residents, promote the inheritance and innovation of rural culture, and provide a strong guarantee for the sustainable development of rural areas. Through the continuous advancement of the rural digital governance platform, it is anticipated to achieve the modernization of rural governance, promote industrial prosperity, optimize public services, encourage talent return, and foster cultural inheritance and innovation. This will provide a robust foundation for the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy. Guided by the “digital village” strategy, digital platforms serve as pivotal vehicles for the transformation of rural digital governance. Taking the policymaking process facilitated by the “JuHaoban” platform as a case study, this paper integrates theoretical frameworks with practical applications to construct a “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework. This framework elucidates the policy innovation process at the local-decision-making level under the influence of the central strategy. The findings indicate that the problem stream can be generated through both proactive scanning and reactive response mechanisms, which can operate concurrently. Decision makers at various levels function as policy entrepreneurs, leading the policymaking community, and the policy window can open either opportunistically or continuously, driven by these decision makers. The policy establishment process of Julu County’s “JuHaoban” platform exemplifies an “up-and-down” dynamic, primarily influenced by political streams. By proactively identifying social issues and responding to emergencies, county-level decision makers implement policy innovations in alignment with the “digital village” strategy. The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework provides substantial explanatory power regarding local policy innovation processes within central–local interactions. The conclusions and recommendations offer significant policymaking implications for the development of rural digital governance platforms.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of information technology, digital governance has emerged as a crucial means in China’s social governance. The rural digital governance platform, as an emerging governance model, not only contributes to enhancing the efficacy of rural governance but also holds significant implications for promoting sustainable rural development. By integrating diverse resource information in rural areas, the rural digital governance platform realizes resource sharing and optimal allocation. Through information technology approaches, the rural digital governance platform achieves intelligent and refined rural governance. The rural digital governance platform can facilitate the transformation and upgrading of rural industries and propel the continuous development of the rural economy. It can also uplift the level of public services in rural areas and enhance the quality of life for rural residents. Furthermore, the rural digital governance platform can advance the digitalization and networking of rural cultural resources, facilitating the inheritance and innovation of rural culture.

The transformation of rural digital governance is an important part of the modernization of the national governance system and governance capacity. The influx of information technology into rural areas not only provides tool support for rural governance but also shapes the pattern of rural governance. Digital governance is the process of extending the utility of information technology from inside government organizations to outside organizations. It not only “empowers” the government organizations inside but also “empowers” the public outside [1]. In order to improve the capacity of rural governance, in May 2019, the state issued the Outline of the “Digital Village” Strategy, taking informatization as the basic support in promoting the modernization of the rural governance system and governance capacity and then building a new system of rural digital governance. In 2022, the Cyberspace Administration of the CPC Central Committee and ten other departments jointly issued the Action Plan for Digital Rural Development (2022–2025), which clearly prioritized the improvement of the rural digital governance capacity as a key task. In 2023, the National Rural Revitalization Administration and other departments jointly issued the Key Points for Digital Rural Development in 2023, proposing to rely on the national integrated government service platform to promote the extension of government services to the grassroots and promote the integration of online and offline services for the convenience of the people. The rural digital governance platform is an online public space [2] built by combining digital technology with the basic unit of rural governance. As policymaking resources continue to tilt toward the countryside, the construction of digital villages is accelerated, and various rural digital governance platforms (such as digital Village One map, Tencent “for villages”, and rural E governance) are gradually being established and put into rural governance practice. However, what kind of policymaking process is required to establish rural digital governance platforms in various places? What kind of central–local interactions are involved in this process?

As a result, this study aims to explore the formation process of the rural digital governance platform using the multiple-stream framework, combined with specific case studies, and analyze the interaction logic between central and local decision makers in the policymaking process of rural digital governance.

2. Research Methodology and Literature Review

2.1. Research Methodology

The research methods of this paper mainly include the following aspects: First, theoretical construction. In order to better explain the generation process of the rural digital governance platform theoretically, this paper combines the specific case of the “Juhao Bu” (http://www.julu.gov.cn/, accessed on 18 January 2025) digital governance platform in Jucheng County and the relevant research results of the policymaking process and constructs a “comprehensive perspective–multiple stream” theory. Second, data collection, in-depth interviews, and participant observations. Actual usage data were collected on the “Juhao Bu” digital governance platform (mainly referring to the “Juhao Bu” app), including policy texts and usage process data. In Jucheng County, in-depth interviews and participant observations were conducted with the users of the “Juhao Bu” app to obtain their usage opinions. The specific process is further introduced in the case background later. Third, grounded analysis. Grounded analysis was conducted on the texts and data obtained from data collection and in-depth interviews to summarize the key events “preparation–emergence”.

2.2. Literature Review

The construction of digital governance platforms has significantly enhanced the ability of government departments to rapidly control social situations at the grassroot level, providing robust support for grassroot social governance [3] and driving the transformation of rural digital governance [4]. The integration of digital technology with governance can provide a powerful impetus for improving the efficiency of rural governance and promoting good governance in rural areas [5]. The rural digital governance platform drives reforms in the rural governance system, achieving clarity, intelligence, diversification, and sharing in rural digital governance [6]. As a key vehicle for rural governance [7], the rural digital governance platform promotes the realization of convenience, refinement, and intelligence in rural governance. With the development of rural digital governance practices, the rural digital governance platform has become a focal point of academic interest, primarily focusing on the following three aspects of research findings:

First, this paper discusses the necessity of applying the digital governance platform to governance practice. As a formal vehicle for digital governance, the rural digital governance platform utilizes digital space as a means to construct digital, information-based, and intelligent governance mechanisms, thereby enhancing rural governance capacity and facilitating its transformation [8]. The digital transformation of government governance is essential for promoting the modernization of the governance system and capacity [3]. The rural digital governance platform offers several advantages [5], including data integration, interconnectivity and collaboration, agility, and convenience, as well as comprehensive oversight.

Second, this paper examines the functions of the digital governance platform. Theoretically, scholars argue that the rural digital governance platform can reshape the rural governance structure, enhance the precision and intelligence [9,10,11,12] of rural governance, and play a positive role in integrating governance stakeholders, consolidating governance resources, and optimizing governance frameworks. Practically, various digital governance platforms established nationwide exhibit distinct functional emphases: Tencent’s “For the Village” platform facilitates multi-stakeholder participation in governance [13]; the “Cunqingtong” app, in Zhangwang Village, Longyou County, supports decision making through big data analysis [14]; the “TWC platform” integrates multiple functions, such as party affairs, village affairs, business, public services, and social services, into a unified platform to achieve comprehensive management [15]; and C County, in Ganzhou City, leverages WeChat groups for the publicity and supervision of village affairs [2].

Finally, this paper analyzes the tension and relief after the digital governance platform is embedded in governance practice. Traditional rural governance exhibits distinct “local” characteristics, and the advent of digital governance has begun to impact the traditional governance model [16], leading to the reconstruction of the basic order and social ecology of rural society [17]. This transformation has introduced more tension during the reconstruction process. At a theoretical level, the imbalance in the interests of multiple stakeholders constitutes internal resistance [18] to the transformation. External factors, such as the blockage of the rural governance culture, an inadequate equal consultation mechanism, and the “movement” of collaborative actions, create collaborative inertia that hinders the effectiveness of rural digital governance [19]. Additionally, the transformation weakens individual emotional identity and moral consciousness, leading to digital identity anxiety among digitally vulnerable groups [20]. Moreover, the performance and promotion of competition among governments at various levels in platform construction, coupled with insufficient social participation led by the government, can result in the “decoupling” dilemma of the rural digital governance platform [21]. In practice, the “One Map of the Digital Countryside” platform addresses the challenges of the fuzzy-logic-based approach, fragmented process, and digital suspension in governance practice through technology empowerment, platform thinking, and value co-creation [6]. However, platforms such as “Agricultural affairs”, “Community”, and “Longyoutong” face real-world dilemmas, including unclear governance concepts, imperfect governance systems, inadequate governance mechanisms, insufficient infrastructure, and low levels of public participation. Concerted efforts from multiple aspects are necessary to promote the improvement of the digital governance model for grassroot governments [22]. In response to the widespread “decoupling” pattern observed in the early stages of rural governance’s digital transformation, concerted efforts should be made in four areas: overall platform construction, capacity enhancement, responsiveness to needs, and public participation enthusiasm [21].

To sum up, existing studies affirm the governance significance of the rural digital governance platform, elucidate its functions from both theoretical and practical perspectives, and analyze the tensions arising from embedding the platform in governance practices, along with potential mitigation paths. However, research on the formation process of the rural digital governance platform and the interaction logic among decision makers at different levels during this process require further strengthening. In light of this, this paper aims to explore the formation process of the rural digital governance platform using the Multiple-Stream framework, combined with specific case studies, and analyze the interaction logic between central and local decision makers in the policymaking process of rural digital governance.

3. Theoretical Analytical Framework

The policymaking process is considered as one of the core issues in policy science research [23]. When founding policy science, Lasswell emphasized the importance of “knowledge of the policymaking process” [24]. Almost all the policymaking process theories cannot avoid addressing social problems, which are regarded as established facts and the logical starting points of public policy [25]. According to Thomas R. Dye, agenda setting in public policymaking involves identifying social problems and proposing potential solutions [26]. Moreover, whether a social problem can attract political attention and prompt administrative intervention after its exposure is also considered as crucial for establishing the agenda [27]. To better explain these issues theoretically, this paper constructs a “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework based on specific cases and relevant research findings in policymaking processes.

Policymaking process theory integrates factors such as actors, groups and networks, institutions, the external environment, and ideas in public policy research and is, therefore, also referred to as the “comprehensive theory” [28]. Both absorbing insights from decision-making theory and enhancing the explanatory power of the theory are important avenues for developing policymaking process theory. Scholars have begun to integrate diverse theoretical frameworks into a unified framework [29]. To better explain the generation process of rural digital governance platforms theoretically, this paper combines specific case studies and relevant policymaking process research findings to construct a “comprehensive multi-stream” theory.

In rural governance, from the perspective of economic geography theory, the construction of digital governance platforms has close relationships with rural digital transformation and rural development. Digital governance platforms contribute to optimizing resource allocation. Through collecting and analyzing various types of data in rural areas, digital governance platforms can provide decision-making bases for governments, enterprises, and farmers, realizing the rational allocation of resources. In [30], for example, in the field of agricultural production, digital governance platforms can monitor the growth conditions of crops and meteorological changes in real time, offering scientific planting guidance for farmers and enhancing agricultural production efficiency. Second, digital governance platforms are conducive for improving the level of rural governance. By establishing an information sharing platform, digital governance platforms can facilitate communication and collaboration among governments, enterprises, and farmers, enhancing the transparency and fairness of rural governance. Meanwhile, digital governance platforms can also achieve intelligent rural governance. In [31], for instance, using big data analysis to predict rural development trends, they can provide strong support for government decision making. Third, in [32], digital governance platforms help to promote rural industrial development. Digital governance platforms can offer all-around services, such as market information, technical support, and financial services, for rural industries, facilitating the transformation and upgrading of rural industries. For instance, through digital governance platforms, agricultural products can be sold online, broadening sales channels and increasing farmers’ incomes. Additionally, digital governance platforms are beneficial for improving rural infrastructure. By integrating various resources, digital governance platforms can promote the construction of rural infrastructure, such as roads, water conservancy, and electricity, providing a powerful guarantee for rural development [33].

3.1. Mixed-Scanning Model

The Mixed-Scanning model is a “third decision-making” approach [34] proposed by Amitai Etzioni as a critique of the impracticality of absolute rationality assumptions and the conservative nature of incremental decision making. Etzioni illustrates the principle of the Mixed-Scanning model using the analogy of satellite-scanning lenses: wide-angle, low-resolution cameras that provide an overview of the entire space without focusing on details, while high-resolution cameras perform deep, detailed scans. In practice, it is essential to combine these “two lenses”, using wide-angle scanning to provide a broad context for more focused, magnified observation [35]. On this foundation, Etzioni distinguishes between fundamental decisions and progressive decisions. Fundamental decisions are higher-order choices that set overarching directions, while progressive decisions lay the groundwork for and implement these fundamental decisions. Etzioni argues that the specific type of decision is influenced by the decision maker’s level, environment, and control capabilities.

Although the comprehensive view model has been criticized for its lack of detailed elaboration on specific operational procedures, its distinction between fundamental and incremental decision making remains reasonable. In China’s policymaking environment, most policies are formed through a series of incremental decisions guided by strategic decisions. The comprehensive view model not only explains the generation process of fundamental decisions and their subsequent incremental decisions but also highlights the role of decision makers in identifying and responding to social issues. It demonstrates how some social issues are incorporated into the policymaking agenda from the perspective of decision makers, thereby providing a theoretical framework for a more comprehensive examination of social issues.

3.2. Multiple-Stream Theory

The Multiple-Stream Theory is a policymaking process framework proposed by John W. Kingdon in the 1990s, building upon the “Trash Can Model of Decision Making” developed by Olsen et al. This theory moves away from the linear thinking mode of absolute rationality and the incrementalist approach, emphasizing, instead, the role of contingencies in shaping the policymaking agenda. According to Kingdon, problems enter the policymaking agenda through the convergence [36] of three streams: the problem stream, the policy stream, and the political stream.

Since its introduction to China, the Multiple-Stream Theory has been widely applied in research on public policymaking processes, including land issues, housing issues, urban asylum and repatriation issues, and education issues [37]. In recent years, it has also been used to analyze environmental protection, education, healthcare, and other policy areas. The Multiple-Stream Theory possesses strong explanatory power for the policymaking process. Renowned policy scholar Paul A. Sabatier [38] argues that this theory can address challenges in agenda setting and policy selection across different national systems. However, given that the theory was developed within the political context of the United States, questions inevitably arise regarding its applicability to China’s policymaking practices.

In the existing literature, most studies have merely applied the Multiple-Stream Theory in a simplistic manner [39], lacking an in-depth examination of its applicability, feasibility, and explanatory power in China’s policymaking practices [40]. In reality, no single decision-making model is universally suitable for all environments; instead, it is crucial to determine which model is more effective under specific conditions [41]. Regarding the Multiple-Stream Theory, the three streams exhibit varying coupling patterns with the social, political, and economic structures of different countries [42]. Some domestic scholars have recognized this and begun exploring the coupling patterns of multiple streams within the Chinese context: Wen Hong and Cui Tie [43] discuss the characteristics of China’s decision-making process, emphasizing the dominant role of the political stream among the three streams. Wang Ying and He Huabing [44] affirm the applicability of the Multiple-Stream Theory in analyzing China’s policymaking processes by examining Guangzhou’s “no-motorcycle” policy. They also highlight the theory’s limitations when applied to specific issues under China’s unique national conditions, political system, and management structure. Ma Li et al. [45] focus on the status and role of the policymaking community within the Multiple-Stream Theory. Chen Guiwu et al. [46] divide the policy formation process into two stages—response and policy formulation—based on the varying strengths and weaknesses of the three streams during agenda setting.

3.3. The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” Model: A Revision of the Multiple-Stream Framework Based on China’s Policymaking Process

To construct a policymaking process theory with Chinese characteristics, two key resources must be utilized: public policy theory and the practice of public policymaking. To elucidate the process by which local governments generate public policies under the guidance of the central government in China’s policymaking process, this paper examines the policymaking practice of Julu County in Hebei Province in establishing a “JuHaoban” rural digital governance platform. Building on Ning Sao’s [47] “coming and going up and down” model, which is grounded in China’s public policymaking practice, this study integrates the reasonable theoretical core of Amitai Etzioni’s Mixed-Scanning model and John W. Kingdon’s Multiple-Stream Theory. The aim is to establish the “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” model, thereby constructing a local policymaking process interpretation framework based on China’s policymaking process practice.

Although the Multiple-Stream Theory possesses strong explanatory power, it is inevitable that specific events under China’s unique political and organizational systems may be “unacclimated” to this framework. In China’s policymaking practice, the convergence of multiple streams exhibits the following characteristics:

- Each source stream is not independent; there exists a hierarchical relationship [48] between the streams within China’s characteristic bureaucracy;

- Policy entrepreneurs do not typically promote the opening of policy windows. Only policymakers have the authority to reallocate public resources through organizational or collective power [44];

- The flow of policies is less significant, and the decision-making process in China shows the distinct feature of “Decision Reduction–Implementation Negotiation” [49].

Therefore, efforts should be made to construct a policymaking process model with Chinese characteristics from four aspects: enhancing the integration of sources and streams, centralizing political streams, ensuring the independence of focus events, and accommodating temporary decision making in special cases.

The Multiple-Stream Theory assumes that each stream is relatively independent, although there may be partial convergence [50]. However, the convergence of the three streams is a necessary condition for policy generation. In the context of China’s policymaking process, the combination of the political stream and the problem stream often leads to the formulation of principled policies. The specific operational details are subsequently shaped through various forms of deliberation and consultation during implementation [49]. The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework offers significant explanatory power regarding how social problems are identified and brought into the agenda within China’s policymaking process.

In China’s policymaking process, the Multiple-Stream Theory exhibits a coupling pattern with distinct Chinese characteristics. The national sentiment of “yearning for a better life” and the ruling party’s commitment to “serving the people wholeheartedly” are deeply aligned with the political stream. Guided by this stable political stream, decision makers at all levels conduct wide-angle scanning to identify social problems and then perform in-depth research through focused scanning to form the problem stream. Once the policy window opens, decision makers act as policy entrepreneurs, mobilizing various resources to establish a policymaking community and launch strategic and progressive decisions through consultation. Meanwhile, the development of network technology has made “bottom-up” agenda building nearly as significant as the traditional “top-down” approach [51]. In the event of an emergency, media agendas, public agendas [52], and social media agendas [43] can rapidly emerge and gain attention through online amplification, thereby opening the policy window and incorporating these issues into the agenda.

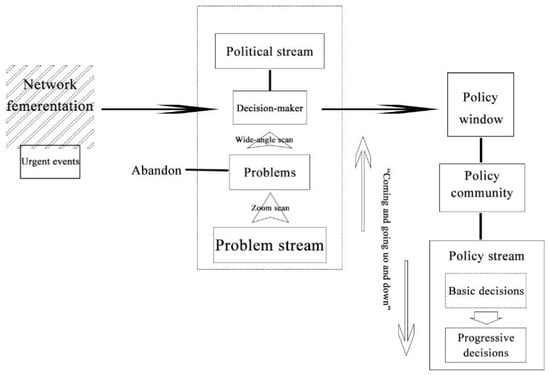

“Coming and Going Up and Down” is a policymaking process concept proposed by Ning Sao [43] in his book Science of Public Policy, grounded in the practice of policymaking processes in China. This model posits that in contemporary China’s public policymaking practice, the process of social understanding of policy moves from “physical” to “metaphysical” and back to “physical”, while the process of policy operation in society follows the trajectory of “coming from the masses and going back to the masses” [53]. Within the framework of the “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” model, the process by which social problems rise to become public policy is one of “practice–cognition”, and the progression from basic decision making to progressive decision making is characterized as a transition from “general” to “individual” (See to Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework.

4. Case Embedding: The Generation Process of Julu County’s “JuHaoban” Platform

4.1. Case Background

As an important carrier of rural digital governance, the rural digital governance platform is a critical component of the construction of digital villages. Since the introduction of the digital village strategy, regions like Zhejiang have taken the lead in establishing numerous rural digital governance platforms, which have gradually integrated into governance practices and formed relatively comprehensive governance models. In these regions, supported by a solid digital industry foundation and pilot policies, rural digital governance platforms have been established through a process of “crossing the river by feeling the stones”. The “pilot-popularization” approach is a significant method of decision making in China, and how to promote successful pilot policies is a topic worthy of study. Therefore, this paper selects Julu County for a case study on the agenda-setting process for establishing the “JuHaoban” platform, which is both representative and feasible: (1) Julu County, as an agricultural county with a relatively weak digital industry foundation, has become a typical example of national digital governance through the establishment of the “JuHaoban” platform. (2) Julu County’s digital governance platform was developed by learning from other platforms and achieved success despite being established later and without the support of pilot policies. This innovative application offers a valuable reference for the establishment of digital governance platforms in central and western regions.

The “Juhao Bu” digital governance platform in Julu County was initiated in May 2020. It is an online comprehensive service management platform with functions such as event reporting, handling, and feedback. Its main users include the public, grid workers, and government departments. Its application scope covers all the villages and communities in the county. The start time: The platform was completed and began operation in May 2020. The functions of “Juhao Bu”: The platform sets up a “five-step workflow” process, including event reporting, classification acceptance, response designation, department handling, and result feedback. In addition, it has developed a series of functions, such as immediate handling, help handling, convenient payment, Juhao Bu learning, and immediate supervision, covering various application scenarios, such as party building, daily payment, information inquiry, and problem feedback, achieving one-stop service on a single platform. The users of “Juhao Bu” mainly include (1) the public. The public can log in to the “Juhao Bu” platform by scanning a QR code to reflect various demands and directly upload them to the county’s dispatch and command center, achieving 24-h, mhour uninterrupted complaint handling. (2) Grid workers. Grid workers actively identify problem hazards and understand public demands in the streets, alleys, and fields through the “immediate handling” application module and report them through one-click operation to achieve closed-loop handling. (3) Government departments. Government departments receive, handle, and provide feedback about public demands through the platform. At the same time, the secondary management platform of the town submits the reported information for preliminary screening and classification. For those that cannot be resolved, they are submitted to the county’s comprehensive dispatch center, which promptly transfers them to the designated department for handling according to the responsibility list. The application scope of “Juhao Bu”: The application scope of the “Juhao Bu” platform covers all the villages and communities in Julu County, achieving full-area coverage of grid management. Through the “Juhao Bu” platform, Julu County has explored the digital empowerment of grassroot governance and promoted the improvement of service quality for the public and the efficiency of work implementation [54].

To further understand the generation path of Julu County’s rural digital governance platform, the research group conducted multiple visits to Julu County from April to June 2023 and from October to November 2024. These visits included the county’s big data center, township-level digital governance sub-centers, and village-level digital governance platforms. During these visits, the research team carried out in-depth interviews and participatory observations, compiling over 120,000 words of recorded text and related materials. The data primarily came from three main sources:

- (1)

- **Participatory Observations**: Research group members visited the big data center and conducted longitudinal observations of Julu County’s rural digital governance platform, accumulating a substantial amount of first-hand data;

- (2)

- **In-Depth Interview Data**: The research team organized several semi-structured interviews and discussions with key personnel involved in the three-tier “Juhaoban” platform in Julu County, including other staff members of the digital governance platform, grid leaders, grid personnel, and some users, resulting in detailed written records;

- (3)

- **Other Data Materials**: This category includes policy documents, meeting minutes, news reports, and other compiled materials.

Additionally, to ensure the timeliness of the case materials, the research group conducted an online follow-up visit.

4.2. Case Description

Julu County, located at the edge of the North China Plain in Hebei Province, administers eight towns and two townships, with a resident population of 321,500. In 2020, Julu County initiated the exploration for establishing a digital governance platform, subsequently developing a “down-call up-response” system to collect, classify, summarize, process, and supervise public demands. By 2022, this platform was upgraded and renamed as “JuHaoban”, launching a dedicated mobile application. Through the mobilization of the digital governance platform, the county achieved comprehensive functions, including publicity, information collection, and event processing. Additionally, over 2800 grid personnel facilitated three-level linkage between the county, town, and village levels, enabling convenient and efficient rural digital governance. The establishment of the platform addresses several key issues: identifying problems, locating solutions, determining where to address them, and understanding the process. In 2024, the “JuHaoban” platform was recognized as one of the fourth batch of national digital governance typical cases. As the sole county-level unit, it was featured at the China International Digital Industry Expo.

4.2.1. “Pressure Transformation”: The Transformation Dilemma Under Multiple Pressures

Economic Challenges. Julu County is a typical agricultural county, primarily focused on plantation industries, and was classified as a relatively poor county until it achieved poverty alleviation in 2019. The county covers an area of 631 square kilometers, with a permanent population of 346,000. Its GDP in 2019 was CNY 9.82 billion. In 2020, Julu County began exploring the establishment of a digital governance platform, acquiring technical support through procurement. Maintaining the efficient operation of the digital governance system requires sustained financial investment, presenting a significant challenge for Julu County.

Application Pressure. Julu County’s primary industry is agriculture, with recent developments in the manufacturing sector. Although the information industry has made some progress, it remains in its early stages. The lack of an industrial foundation makes it challenging to establish an efficient digital governance platform that meets local needs and integrates seamlessly into governance practices. Additionally, Julu County faces a significant demographic challenge because of the outflow of young people, resulting in a rapidly aging population. Currently, the elderly population accounts for 20% of the total population and is increasing annually. As the trend of young people migrating to cities continues, the proportion of the elderly population in Julu County has further increased. To achieve effective digital governance transformation, it is crucial to include the elderly population. However, many elderly residents lack the necessary knowledge and skills, making it difficult to bridge the “digital divide” during this transition.

The Pressure of Expectations. The establishment of a digital governance platform, coupled with its integration into governance practices, faces dual expectation pressures from both the public and leadership groups. In terms of public expectations, improving work efficiency and simplifying procedures are major national concerns and common societal expectations. As digital technology continues to permeate production and daily life and various digital platforms are launched, the residents of Julu County also anticipate achieving convenient business management through digital governance platforms. Regarding pressure from leadership groups, Julu County was formerly a national-level impoverished county with limited economic resources. Investing substantial funds in constructing a digital governance platform underscores the leadership’s commitment to this initiative, which naturally brings high expectations. Therefore, Julu County must establish an effective digital governance platform and successfully integrate it into governance practices to meet these expectations.

4.2.2. “Platform Embedding”: Tension Relief in the Running-In Process

In 2020, Julu County established the “down-call up-response” platform based on Dingding and transferred some functions to this platform. Despite vigorous promotional efforts, the utilization rate of the platform remained low, leading to a period of “digital suspension” for the digital governance platform in Julu County. After leadership changes in 2022, the new administration placed greater emphasis on the development of the rural digital governance platform. To address the challenges posed by integrating digital technology into governance practices, Julu County recruited and screened over 2800 individuals to form a grid team, renaming the “down-call up-response” platform as the “JuHaoban” platform. The grid team incorporates various rural service personnel, such as human settlement environment inspectors and epidemic prevention grid personnel, collectively referred to as comprehensive grid personnel. Each comprehensive grid member receives a monthly subsidy of CNY 300 from the county’s finance department and participates in regular training sessions.

The establishment of the grid staff enables the “JuHaoban” platform to begin integrating into the daily lives of the residents. Through the “JuHaoban” platform, residents can directly report issues they encounter in their daily lives. Upon receiving these reports, grid staff promptly address the problems. For issues beyond their capacity, the grid staff can escalate them to higher management via the platform’s grid manager function. The public can monitor the handling process of reported events in real time on the platform. Additionally, even without using the “JuHaoban” platform, residents can still provide feedback by contacting nearby grid staff.

4.2.3. “Function Debugging”: Function Optimization Under In-Depth Investigation

After the establishment of the platform, Julu County has continuously enhanced the functionalities of the “JuHaoban” platform to achieve better integration with governance practices. Based on in-depth research into the needs of residents, various practical functions have been incorporated into the platform, for instance:

- (1)

- To realize the goal of “letting data run more and reducing errands for residents”, a “Help Me Do” section was established on the “JuHaoban” platform. This section handles comprehensive government affairs, such as issuing certificates, processing disability permits, stamping documents, and elderly care services;

- (2)

- To ensure “immediate action”, Julu County introduced an “Immediate Action” module. Through this feature, residents can report incidents and track real-time processing progress via the platform;

- (3)

- To address issues of “failure”, Julu County set up a “Failure Resolution” window in the government service hall to resolve various difficulties encountered by residents during business transactions.

After the governance practice and application of the “JuHaoban” platform, Julu County has established a three-tier platform structure, encompassing county, township, and village levels. This three-tier platform realizes different functional focuses based on specific requirements: The village-level platform primarily handles news dissemination; the township-level platform focuses on information collection and storage, and the county-level platform concentrates on event processing. According to a responsible person for the “JuHaoban” platform in Z Town, a Township in Julu County: “Our platform updates information in real time. For example, if a child is born in a villager’s family, the villager can update this information on the platform themselves, or the grid officer can update it during household visits.” The “JuHaoban” platform closely links government departments, grid staff, and users, dividing platform functions into different levels according to needs, thereby achieving efficient processing of events reported by residents.

To enhance the convenience of the “JuHaoban” platform, Julu County has continuously expanded its usage scenarios. While retaining the initially established Dingding platform, it has developed a dedicated “JuHaoban” app and recently launched a WeChat mini program. The platform has simplified the login procedure, allowing villagers to log in quickly by receiving a verification code. After the first login, the WeChat mini program enables one-click login on a local device. These convenient login methods and multiple login channels have alleviated the tension between the platform and governance practices, enabling Julu County to successfully realize the transformation of digital governance. As one villager from T Town noted: “In the past, we used to discuss what kind of nails to use, which I didn’t understand. Now, the grid officer has directly installed the ’JuHaoban’ app on my mobile phone, and I can take photos to report issues very quickly”.

4.2.4. “Governance Coupling”: Demand Response in Continuous Optimization

Application optimization on the “JuHaoban” platform continuously enhances users’ experiences. Following the launch of the “JuHaoban” WeChat mini program, the user base has significantly expanded, and the platform has become an integral part of Julu County’s social governance. To further enhance the platform’s convenience and lower the usage threshold, Julu County extensively gathered user feedback during platform utilization. Consequently, the management module now includes convenient features, such as voice input, a large font mode, and a grid member address map.

Governance efficiency has significantly improved, and the “Juhao” platform has integrated a point system. To further leverage the role of the digital governance platform and enhance the enthusiasm of the grid personnel and users, Julu County has incorporated the point system into the digital platform. Grid personnel and users can earn point rewards after reporting and resolving events, which can be redeemed for daily necessities. Since the implementation of the point system on the “JuHaoban” platform, many previously overlooked issues have been addressed, particularly leading to substantial improvements in the living environment.

Functional integration has transformed “Juhao Ban” into a comprehensive platform for public convenience. Julu County has continuously embedded various commonly used websites into the “Juhao Ban” platform to enhance its functionality. Through modular design, the platform integrates the following multiple services:

- (1)

- The Life Service Module enables users to perform daily tasks, such as payments, package tracking, job searches, and ticket purchases;

- (2)

- The Government Service Module facilitates seamless one-click navigation between the “Juhao Ban” platform and other key platforms, including the county-level People’s Congress digital platform, the county-level judicial digital platform, traffic management 12123, and policy information platforms;

- (3)

- The Rural E-commerce Module provides villagers with convenient online shopping options while expanding sales channels for agricultural products. The platform also offers a unified packaging design, quality control, and other services, gradually establishing the Julu agricultural specialty brand.

(Julu County T Town villager B: “As you can see, this is a video we took a few days ago. In it, Lao Yang used the “Juhao Ban” platform to consult agricultural experts about honeysuckle planting. I tried it too and was pleasantly surprised when an expert actually came to help!”)

5. Interpretation of the Path Formed by the Rural Digital Governance Platform

5.1. “Brewing”: A New Round of Reform to Streamline Administration and Delegate Power Leads to “Problem Flow”

Aite Aoni emphasized the influences of different levels of decision makers and their control capabilities on policy establishment. From the perspective of Julu County’s development of the “JuHaoban” digital governance platform, this initiative represents an exploration under the guidance of the “digital village strategy”, tailored to local needs. The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” model can explain how social issues are brought into the agenda of decision makers at various levels. From the top-level decision makers’ perspective, the CPC Central Committee and the State Council identified complex issues in people’s business processes through wide-angle scanning. Subsequently, they conducted in-depth research via zoom scanning to form the problem stream. The convergence of the political stream and the problem stream successfully opened the policy window. Through comprehensive discussions and research by the policymaking community, the policy stream was formed, leading to the proposal of the “digital village” strategy as a fundamental decision.

Before the establishment of the “JuHaoban” platform, Julu County handled all kinds of business at the government affairs service hall. During this period, the public exhibited a relatively indifferent attitude. Matters closely related to their own interests were processed at the government affairs service hall, while less-relevant matters were often neglected. These neglected public affairs accumulated over time, leading to direct infringements on some individuals’ interests and increasing dissatisfaction with the governance system. In 2020, Julu County implemented administrative simplification and power delegation reforms, delegating many functions to townships. However, the public was often unaware of which departments to approach for specific services, resulting in lower efficiency in business management. Additionally, township staff lacked proficiency in handling new functional tasks, further contributing to inefficiency. As a result, some residents expressed their frustrations online, posting about difficulties in managing official business on social media platforms. This led to significant pressure on Julu County from letters and visits, as well as online public opinion. (The head of the Big Data Center of Julu County: “In fact, this situation presented an opportunity for the formation of our platform. In 2020, the county initiated administrative simplification and power delegation reforms, dividing many functions among townships. However, many people were unaware of these changes and had to run back and forth between county and township offices”).

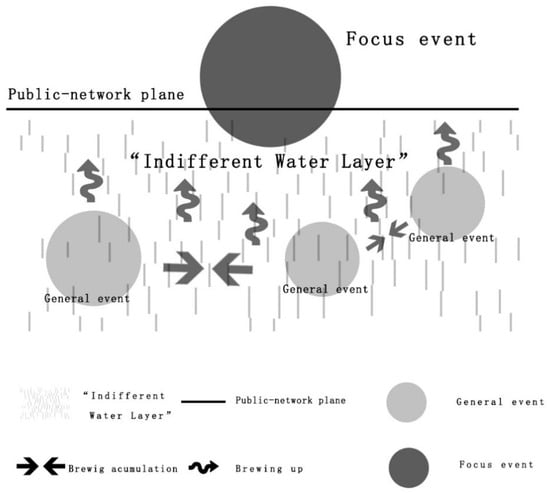

In the policymaking process for establishing a digital governance platform in Julu County, the formation of the problem stream is a gradual process of “brewing–emerging”. Prior to the institutional reform in Julu County, the public exhibited a relatively indifferent attitude toward the governance system. Because decision makers did not identify and address the shelved social issues during their initial scans, public discontent began to accumulate. After the institutional reform, the combination of prolonged business processing cycles and inefficient business management exacerbated this dissatisfaction. Under the pressure of online public opinions, letters, and visits, the rapid expansion of public discontent eventually escalated into an emergency, which quickly drew the attention of decision makers and formed a significant problem stream (See to Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“Brewing–emerging” of focal events.

The data coding materials for the “brewing–emerging” of focal events are derived from the records of interviews with the masses during the policy implementation process and the collected materials through channels such as online public opinions, letters, and visits. The main data coding encompasses (1) The records of interviews with the masses during the policy implementation process: ① the indifferent attitude of the masses toward the governance system; ② the dissatisfaction of the masses with policy formulation, execution, and other aspects; ③ problems such as prolonged business-processing cycles and inefficient business handling. (2) The collected materials through channels such as online public opinions, letters, and visits: ① the masses expressing dissatisfaction through online channels, letters, visits, etc.; ② public opinion focusing on the problems during the policy implementation process; ③ the attention and response of decision makers to the problem flow. Through the analysis of the data coding materials, it can be discovered that (1) the indifferent attitude of the masses toward the governance system is closely related to the problems during the policy implementation process and is the main manifestation in the brewing stage; (2) problems such as prolonged business-processing cycles and inefficient business handling are the main causes for the brewing of the dissatisfaction of the masses; (3) online public opinions, letters, visits, etc. are the main channels for the dissatisfaction of the masses to surface and play a crucial role in forming the problem flow for decision makers. To sum up, through grounded theory interpretation, we can clearly observe how the “brewing–surfacing” process is formed in the policymaking process for establishing a digital governance platform in Julu County. This process reveals the problems existing in the policy implementation process and provides beneficial inspirations for policy improvement and optimization.

5.2. “Cooperative Incubation”: Coordinated Output of the “Policy Flow” Within the Policymaking Community

Before 2019, Julu County was designated as a national-level poverty-stricken county. During the poverty alleviation process, Alibaba’s village work team provided guidance and assistance in constructing e-commerce platforms. In 2020, Julu County began exploring the establishment of a rural digital governance platform, and the Alibaba Village Work Team was integrated into the policymaking community to participate in the platform’s construction. With technical support from the Alibaba Group, Julu County developed its first-generation rural digital governance platform using DingTalk (https://mydown.yesky.com/pcsoft/413570022.html, accessed on 18 January 2025) as the technical foundation. Subsequently, Julu County brought in a group of experts and scholars to join the policymaking community to address challenges encountered during the platform’s application and implementation.

The convergence of the political stream and the problem stream successfully opened the policy window, prompting decision makers in Julu County to explore policy solutions. In the context of the central-decision-making-level scanning of social problems and proposal of the “rural revitalization” and “digital village” strategies, Julu County aligned its priorities with those of the central government [41]. This alignment fostered a tendency toward gradual implementation of the strategic decisions proposed by the central government. Guided by the “digital village” strategy, local decision makers led the formation of a policymaking community and began exploring the establishment of a digital governance platform by integrating the policymaking community with existing practical experience.

5.3. “Dual Response”: Strategic Orientation and Public Expectations Constitute “Political Flow”

In Guindon’s “Multiple-Stream Theory”, the political stream encompasses national sentiment, government changes, and local elections. In the Chinese context, the political attitude at the national level and public sentiment at the social level constitute the political stream for establishing a rural digital governance platform. Regarding political attitude, the party and government bodies at all the levels in China are committed to serving the people and actively promoting the construction of digital governance platforms. Concerning public sentiment, although people have limited understanding of digital governance platforms, they recognize that improving governance effectiveness is closely tied to their own interests, leading to social support for the development of these platforms. With the strategic orientation proposed by the central-decision-making level and the public’s expectation of achieving convenient government services through digital governance, Julu County has established a stable and powerful political stream.

5.4. “Continuous Attention”: The Foundation for the Establishment and Development of the Platform

In public policy research, the attention of decision makers has always been valued by the academic community as a scarce resource. The establishment of a rural digital governance platform in Julu County and its becoming a typical example of national digital governance cannot be achieved without the continuous attention of decision makers. The “digital countryside” strategy covers many aspects and is an overall and long-term rural development plan, which reflects the long-term concern of the central-decision-making level for rural digital transformation. After Julu County established the “JuHaoban” rural digital governance platform, the county-level decision-making level followed the “digital village” strategy to continue to zoom scan the platform operation, constantly forming a problem stream of local “decoupling” between digital platform and governance practices, and then more subjects were incorporated into the policymaking community and continued to generate policies to alleviate this local “decoupling” phenomenon.

6. Conclusions

This paper focuses on how local governments introduce policies under the strategic guidance of the central government and in response to local realities, analyzing the process for establishing the “JuHaoban” rural digital governance platform in Julu County. Based on the logic of “coming and going” in China’s policymaking practice, this study constructs a “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework by integrating elements from the Mixed-Scanning model and the Multiple-Stream framework. The paper theoretically explains the internal logic of central and local interactions during the introduction of local policies. Building on China’s local policymaking processes, this study makes several additions to the Multiple-Stream Theory and explores the characteristic coupling patterns of three streams in China’s policymaking process:

- (1)

- In China’s policymaking practice, the policymaking process exhibits an obvious feature of “decision-making abatement–implementation consultation”. When the political stream and problem stream converge, the policy window can be opened. After the policy window opens, decision makers can seek specific policy solutions through the policymaking community;

- (2)

- Policy entrepreneurs are typically high-level leaders with decision-making power who organize and lead the policymaking community during policy introduction;

- (3)

- The problem stream is generated through various means. It can be identified through mixed scanning by decision makers or rapidly formed because of strong pressure from emergency events. Both methods can jointly promote the generation of the problem stream;

- (4)

- The policy stream at different levels exhibits homologous preferences. After the central-decision-making level formulates general and directional strategic decisions, the local-decision-making level follows these “central preferences” to make progressive decisions;

- (5)

- The policy window can remain open continuously. In classical Multiple-Stream Theory, the opening of the policy window is considered as accidental and fleeting. The “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Stream” framework retains the randomness of the policy window opening because of accidental events while incorporating the scenario where the policy window is opened through top-down leadership within the political stream.

The above conclusions have a certain reference value for other regions as well, mainly reflected in the following three aspects:

First, they provide a reference for policymaking in other regions. The characteristic coupling patterns in China’s policymaking process offer new ideas for policymaking in other regions. For instance, emphasizing “decision reduction–implementation consultation” during the policymaking process can reduce resistance in policy implementation and improve its efficiency; the role of policy entrepreneurs in the policymaking process can enhance the policy innovation ability and execution capacity; the diverse generation methods of problem flows provide more ways for other regions to discover and solve problems during policymaking.

Second, they offer a reference for policy evaluation in other regions. The characteristic coupling patterns in China’s policymaking process provide beneficial references for policy evaluation in other regions. For example, focusing on “decision reduction–implementation consultation” during policy evaluation can help to assess the effectiveness of policy implementation; the role of policy entrepreneurs in the policymaking process can be evaluated for assessing the policy innovation ability and execution capacity; the diverse generation methods of problem flows can help to assess the effectiveness of policies in responding to emergencies and long-term issues.

Third, they provide inspirations for policy optimization in other regions. The characteristic coupling patterns in China’s policymaking process provide inspirations for policy optimization in other regions. For instance, in the process of policy optimization, we can draw on the “central preference” mechanism in China’s policymaking process to improve the consistency and coordination of policy implementation; in policy optimization, focusing on the role of policy entrepreneurs can enhance the policy innovation ability and execution capacity; in policy optimization, drawing on the diverse generation methods of problem flows in China can improve the ability of policies to respond to emergencies and long-term issues.

In conclusion, the characteristic coupling patterns in China’s policymaking process have a referential significance for other regions. During the process of borrowing from China, other regions should, based on their own actual situations, implement the successful experiences in China’s policymaking process and continuously optimize the mechanisms for policymaking, evaluation, and optimization to maximize policy goals. At the same time, China should also continue to deepen policy theoretical research and provide more beneficial policy suggestions and practical experiences for other regions.

7. Discussion

Based on the aforementioned insights, this paper proposes the following recommendations and countermeasures: First, it is imperative to strengthen the organizational leadership of the policymaking community and continuously enhance its openness. The policymaking community serves as a “policy factory”, bringing together multiple stakeholders with diverse backgrounds to analyze social issues and generate policy options in accordance with decision makers’ requirements. Establishing a rural digital governance platform is an ongoing process that necessitates a well-structured and open policymaking community. In operation, it is crucial to achieve standardized management and positive interaction among various stakeholders while maintaining openness. This involves continuously identifying various issues in the construction of the rural digital governance platform through detailed scans; incorporating experts, scholars, think tank teams, enterprises, and other relevant parties into the policymaking community based on actual needs; and bridging the gap between the digital governance platform and governance practices.

Second, it is essential to enhance scanning capabilities and ensure smooth feedback channels for social issues. Social issues form the foundation of public policies. In the “Mixed-Scanning–Multiple-Streams” model, social issues can enter the policy agenda through two modes: “scan identification–upper promotion” driven by internal decision makers and “pressure–response–institutionalization” driven by external emergencies. These two modes can also work in tandem. Constructing a rural digital governance platform integrated with governance practices requires a seamless “top-down and bottom-up” process: On the one hand, empowerment from the top by leveraging big data analysis and other advanced technologies to enhance the ability to identify social issues, thereby increasing the breadth and depth of hybrid scanning; on the other hand, focusing on the grassroot level by establishing convenient feedback channels for social issues, ensuring efficient responses to public needs and the timely optimization of platform functions.

Third, continuous attention and support for the construction of rural digital governance platforms are necessary. Decision makers’ attention is a critical resource in the policy proposal and implementation process. The success of the platform hinges on sustained attention and support from decision makers in Julu County. Close attention from the decision-making level provides the impetus to continuously open the policy window, make supplementary decisions to optimize platform functions, and alleviate tensions between the platform and governance practices. Additionally, this attention brings financial support and supervision pressure. Strong financial backing ensures the smooth implementation of policies, while continuous supervision ensures high-quality and efficient construction and operation of the rural digital governance platform.

8. Research Outlook

This paper conducts an empirical analysis solely based on the single case of “Juhao Ban”, presenting certain limitations. Particularly from the practical requirements for the sustainable development of rural governance, there exist limitations in both theoretical construction and practical countermeasures in the following two aspects: On the one hand, limitations are evident in the theoretical construction of this paper. First, the research on the “Juhao Ban” case is primarily based on its existing governance model and practical experiences, lacking in-depth excavation and systematic organization of the theory of sustainable rural governance. This might result in an incomplete comprehension of the issues related to sustainable rural governance, making it challenging to reveal the intrinsic laws and essential characteristics. Second, during the process of theoretical construction in this paper, the interpretation of the “Juhao Ban” case may possess a certain degree of subjectivity, failing to fully take into account other possible theoretical explanations and viewpoints, thereby restricting the objectivity and comprehensiveness of the research. On the other hand, limitations are also present in the practical countermeasures of this paper. First, the practical countermeasures proposed herein are mainly targeted at the specific case of “Juhao Ban”, lacking reference and promotion to other rural governance models. This could lead to a limited scope in the application of the practical countermeasures and make it difficult to be promoted and applied in other rural areas. Second, in the process for formulating the practical countermeasures, this paper might overly rely on the successful experience of “Juhao Ban”, neglecting the problems and deficiencies existing in other rural governance models, thereby reducing the pertinence and effectiveness of the practical countermeasures. To overcome the aforementioned limitations, future related research should be carried out in the following manners:

- (1)

- Thoroughly explore the theory of sustainable rural governance. In terms of theoretical construction, efforts should be made to strengthen the systematic organization and research the theory of sustainable rural governance, draw upon relevant research achievements at home and abroad, and form a relatively complete theoretical system of sustainable rural governance;

- (2)

- Expand the research scope and enhance the representativeness of the research objects. In terms of empirical analysis, representative cases of rural governance should be selected, and in-depth analyses should be conducted from multiple perspectives and levels to improve the universality and credibility of the research conclusions;

- (3)

- Pay attention to the pertinence and operability of practical countermeasures. In terms of practical countermeasures, the actual circumstances of different rural areas should be fully considered, successful experiences should be drawn upon, and targeted practical countermeasures should be proposed in response to existing problems and deficiencies;

- (4)

- Strengthen interdisciplinary research and promote the combination of theory and practice. In terms of research methods, interdisciplinary research should be intensified, and research results and methods from other disciplines should be drawn upon to enhance the scientificity and rigor of the research;

- (5)

- Expand the research perspective and focus on key issues in sustainable rural governance. In terms of the research content, key issues in sustainable rural governance, such as the rural governance system, governance capacity, and governance mechanism, should be focused on to provide beneficial references and inspirations for the sustainable development of rural governance.

In conclusion, the empirical analysis of the “Juhao Ban” case in this paper has certain limitations. To better promote the sustainable development of rural governance, continuous exploration and innovation are needed in theoretical construction and practical countermeasures, with the aim of providing robust support for the sustainable development of rural governance in China.

Author Contributions

B.Z., J.Y., W.X. and B.L. designed the study and wrote the paper; B.Z. and B.L. supervised the writing of the paper; P.Z. and B.L. collected and collated the materials and undertook the field data collection; B.Z. and W.X. are co-first authors; Shandong University and Yanshan University are co-first authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hebei Science and Technology Research and Development Program’s Soft Science Research Project “Research on the Path and Key Measures of Optimizing the Business Environment in Science and Technology in Hebei Province” (No. 24457608D) and the Scientific Research Program Project of the Hebei Provincial Department of Education—Major Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences “Research on the Development of Hebei Province’s Characteristic Industries toward the Sea Economy” (No. ZD202406).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interests that represent conflicts of interest in connection with the submitted work.

References

- Yan, J.; Wang, Z. Digital governance, data governance, intelligent governance and smart governance concepts and their relationship analysis. J. Xiangtan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 43, 25–30+88. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y. The transformation of rural network public space and grassroots governance: A case study of village affairs wechat Group in C County, Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province. J. Fujian Prov. Comm. Party Sch. CPC (Fujian Acad. Gov.) 2021, 1, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Jia, K. Research on the modernization of Digital governance System and governance capacity: Principles, Framework and elements. CASS J. Political Sci. 2019, 3, 23–32+125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. The underlying logic and multiple limits of rural governance empowered by digital platforms: An explanatory framework based on DIKW model. E-Gov 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Luo, S. 3D perspective of digital technology embedded in rural governance. Theor. Explor. 2023, 4, 29–37+105. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Wu, Y. How can Digital Countryside achieve “holistic wisdom governance”?—Empirical investigation based on the panoramic governance platform of “One Map of Digital Countryside” in Wusi Village, Zhejiang. E-Gov 2023, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Yue, X. How to Improve the Efficiency of Rural Digital Governance?—Analysis framework based on data, technology and platform. E-Gov 2024, 1, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, B. Digital Governance: A new model of village governance in the digital countryside. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Wu, H. Digitally empowered rural spatial governance: An explanation based on spatial production theory. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 40, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, B. Digital Empowerment or Digital Burden: Practical logic and Reflection on Digital Rural Governance. E-Gov 2022, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Lu, B. Fit and Adaptation: Practical logic of Digital Governance in Rural Society—A case study of Digital rural governance in Deqing, Zhejiang. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 39, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Deng, S.; Hu, J. Digital technology empowering township government services: Logic, obstacles and approaches. E-Gov 2021, 8, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Dai, Y.; Dong, X. Enabling Mechanism of “Mobile Internet + Village” Model: A case study based on “Tencent For Village”. China Soft Sci. 2021, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J. Operation logic and promotion Strategy of digital rural governance—Based on “LongYoutong” platform. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2022, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Gao, X. How to overcome the trap of “surface digitization” in rural digital governance: An analysis based on the perspective of “citizen as user”. Leadersh. Sci. 2021, 4, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, H. Digital rural governance: Theoretical origins, development opportunities and unintended consequences. Academics 2022, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, J. How digital technology changes rural areas: Based on a survey of 10 villages in 5 provinces. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 40, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Research on multi-subject conflict in digital rural governance. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Deng, J. Patterns, causes and resolution of cooperative inertia in rural digital governance. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 26, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- The dilemma and management of digital identity anxiety: Based on digital village strategy. Soc. Sci. 2022, 4, 82–89.

- Zhao, X.; Chu, Q. The deembedding form and reshaping mechanism of rural governance enabled by digital platforms. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Ye, Q. Operation Logic, realistic dilemma and Optimization Strategy of Digital Governance of grassroots government: An Investigation based on the digital governance platforms of “Agricultural Affairs Tong”, “Community Tong” and “Longyoutong”. J. Manag. 2020, 33, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- He, H. Review and Prospect of Policy Process Theory—Literature Review. Chinese Society of Administrative Management. Seminar on “Building a Harmonious Society and Deepening the Reform of Administrative System” and Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Meeting of Chinese Society of Administrative Management; School of Political Science and Law and Public Administration, Hubei University: Wuhan, China, 2007; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H.D. A Pre-View of Policy Science; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1971; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Bao, L. On the Value appeal and Regression of Constructing Public Policy Problem in our country. Theory Reform 2010, 2, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding Public Policy; Xie, M., Translator; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Shen, Y. The role of media in corporate governance: Empirical evidence from China. Econ. Res. J. 2010, 45, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Decision-making Approaches in Policy Processes: Theoretical Foundations, Evolutionary Process, and Future Prospects. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2017, 46–67, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Wan, L. The Latest Developments, Trends, and Implications of Western Policy Process Theories. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2011, 5, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. The Impact Mechanism of Digital Rural Construction on Land Use Efficiency: Evidence from 255 Cities in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Gong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Jin, X.; Mu, Y.; Lu, Y. Driving Innovation and Sustainable Development in Cultural Heritage Education Through Digital Transformation: The Role of Interactive Technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, D. Can Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone Promote Low-Carbon Urban Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M.; Górecka, D.; Majewska, E. Sustainable Cities and Communities in EU Member States: A Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Mixed-Scanning: A “Third” Approach to Decision-Making; Pergamon: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.-J. Hybrid Scan decision Model: Theory and Method. Theor. Circ. 2014, 5, 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Fong, Y. Analysis on policy agenda setting of “Double first-class” construction from the perspective of multiple streams theory. Fudan Educ. Forum 2021, 19, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P. Policy Process Theory; Shenghe · Dushu · Xinzhi Sanlian Bookstore: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Second Edition and Revised Chinese Edition); Huang, D.; Xing, F., Translators; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Tang, M. Theory validation and Application Field: Theoretical analysis of multiple streams framework—Based on 14 cases. Rev. Public Adm. 2019, 12, 28–46+211–212. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, E.R. Coice in a Changing World. Policy Sci. 1972, 3, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatnous, J.; Wagnerk, M. Tweeting to Power: The Social Media Revolution in American Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Cui, T. Multiple streams Model and its optimization in Chinese Decision Context. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 16, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, H. Multi-dimensional Analysis of Policy Process Theory: A case study of the “Motorcycle Ban” policy in Guangzhou. Chin. Public Adm. 2008, 12, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Luo, J.; Wen, T. How can the Policy Community promote grassroots experiments to be promoted as county policies?—Analysis of multiple streams based on “Labor and Materials Law” in Pingnan County, Fujian Province. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2023, 05, 12–24+123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Lin, X. How does online public opinion shape public policy? A theoretical framework of “two-stage multiple streams”—Taking Hitch safety management Policy as an example. J. Public Manag. 2021, 18, 58–69+168. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, S. Public Policy, 2nd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Luo, J. “Up and down Coming and going”: Agenda-setting of county ecological governance policy: A multiple streams analysis based on purchased afforestation in Daning, Shanxi Province. Chin. Public Adm. 2021, 11, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Zhao, J. Adaptive reform and Limitations of public policy process in transition period. Soc. Sci. China 2017, 9, 45–67+206. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhi, G. Complete or Limited: Structural conditions and coupling mechanisms for policy agenda establishment: An interpretation of a new multiple streams model based on “key individual” variables. Chin. Public Adm. 2020, 12, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, G. Research on policy agenda setting mechanism in network era. Chin. Public Adm. 2013, 1, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. The model of public policy agenda setting in China. Soc. Sci. China 2006, 5, 86–99+207. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, S. Why is China’s Public policy Successful?—Construction and interpretation of policy process model based on China’s experience. Expand. Horiz. 2012, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Jidun Township. In Jiuliu, There Is a Place Called “Jiabangbu” Which Is Very Convenient to Do Business. Available online: http://www.julu.gov.cn/content/53684.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).