Verification of the Assumptions of the Polish State Forest Policy in the Context of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

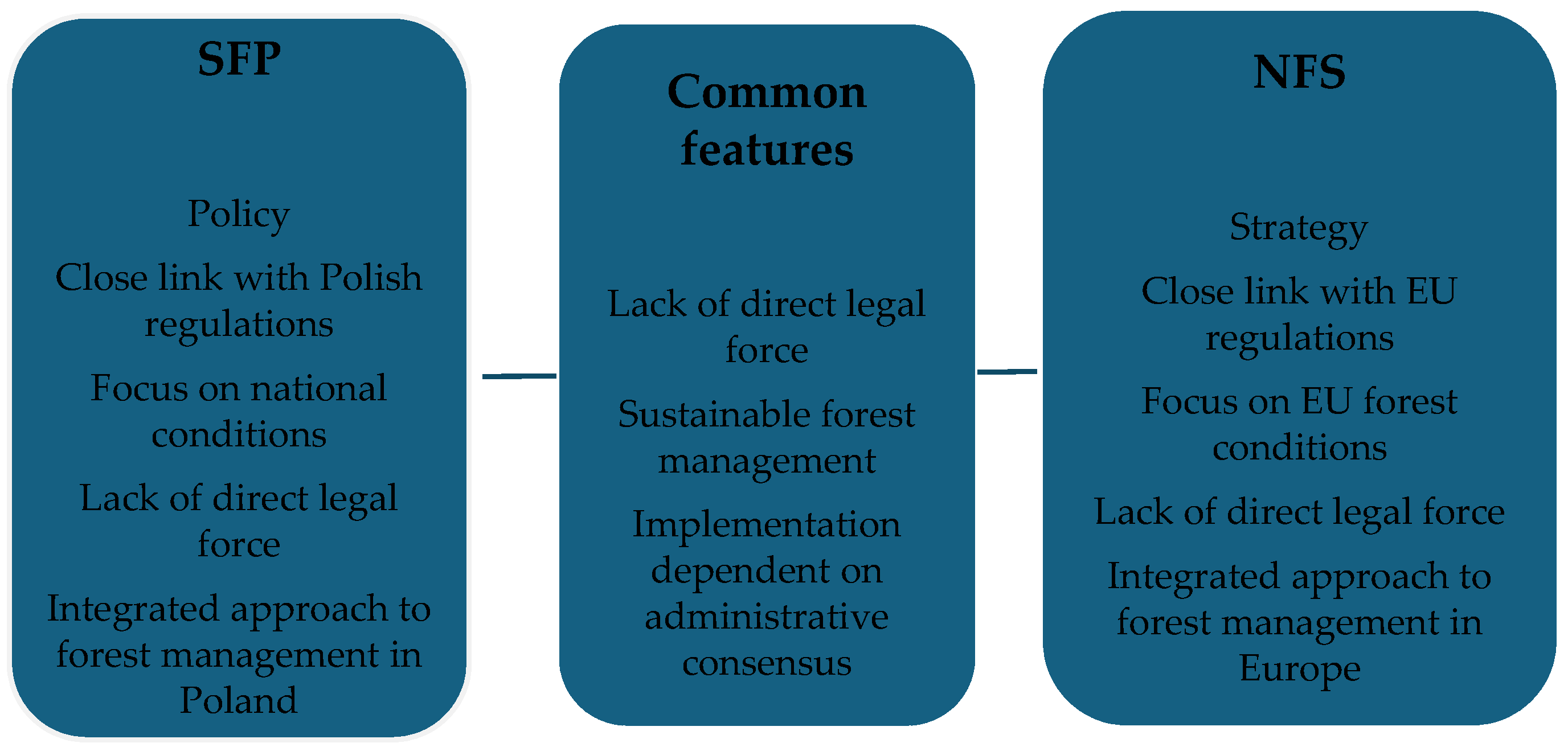

3.1. Forest Policy in Poland and the EU: Assumptions and Strategic Priorities

3.2. Position of the NFS and SFP Within Their Respective Organizational and Legal Frameworks (Legal Implications of Policy Implementation)

3.3. Comparative Analysis of the Priorities of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030 and the State Forest Policy

3.4. Methods for Achieving Objectives Outlined in the SFP and NFS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldous, D.E. Social, environmental, economic and health benefits of green spaces. Acta Hortic. 2007, 762, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Shin, W.S. Forest welfare services—The missing link between forest policy and management in the EU. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G.; Sotirov, M. An Obituary for National Forest Programmes? Analyzing and Learning from the Strategic Use of “New Modes of Governance” in Germany and Bulgaria. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuffic, P.; Sotirov, M.; Arts, B. “Your policy, my rationale”. How individual and structural drivers influence European forest owners’ decisions. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noty Tematyczne o Unii Europejskiej—Parlament Europejski. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/pl/sheet/105/unia-europejska-i-obszary-lesne (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Eurostat. The Eurostat Regional Yearbook; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; ISBN 978-92-68-14307-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa. Ustawa z Dnia 28 Września 1991 r. o Lasach. Dz.U. 1991 Nr 101 Poz. 444. 1991. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19911010444 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Grzywacz, A.; Marszałek, E. Prawne aspekty ochrony przyrody w ekosystemach leśnych. Zarządzanie Ochr. Przyr. Lasach 2007, 1, 14–15. Available online: https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/960099.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Walas, M. Korzystanie z lasów a trwale zrównoważona gospodarka. Repozytorium UMK 2014, 367–377. Available online: http://repozytorium.umk.pl/handle/item/2605 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Radecki, W. Ustawa o Lasach. Komentarz; Wydawnictwo Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Ochrony Środowiska, Zasobów Naturalnych i Leśnictwa. Polityka Leśna Państwa; 22 kwietnia 1997 r. MOŚZNiL; Regionalna Dyrekcja Lasów Państwowych w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 1997; pp. 1–29. Available online: https://www.katowice.lasy.gov.pl/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=506deebb-988d-4665-bcd9-148fcf66ee02&groupId=26676 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Rykowski, K. O lasach w środowisku, czyli skąd przychodzi, gdzie jest i dokąd zmierza polskie leśnictwo. In 100 Lat Leśnictwa w Polsce; Red. W. Szymalskiego. Rozdz. 2; Instytut na Rzecz Ekorozwoju: Radom, Poland, 2020; pp. 164–165. Available online: https://www.pine.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/100lat31102020.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Kaliszewski, A.; Talarczyk, A.; Jabłoński, M.; Michorczyk, A.; Karaszkiewicz, W. Polityczne i prawne ramy opracowania oraz przyjęcia kryteriów i wskaźników trwale zrównoważonej gospodarki leśnej w Polsce (Political and legal framework for formulation and adoption of criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management in Poland). Sylwan 2021, 165, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis-Jakubowicz, P. Polskie leśnictwo w Unii Europejskiej; Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Zmieniający Traktat o Unii Europejskiej i Traktat Ustanawiający Wspólnotę Europejską, 2007, (2007C 306/01). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:C2007/306/01 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Baron, F.; Bellassen, V.; Deheza, M. The Contribution of European Forests-related policies to climate change mitigation: Energy substitution first. Clim. Rep. 2013, 40, 1–40. Available online: https://franceintheus.org/IMG/pdf/13-04_climate_report_40_-_the_contribution_of_european_forest_to_climate_change_mitigation.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Rezolucja Parlamentu Europejskiego w Sprawie Klęsk Żywiołowych (Pożarów, Susz Oraz Powodzi)—Aspektów Związanych z Ochroną Środowiska Naturalnego (2005/2192(INI)). Available online: https://op.europa.eu/fi/publication-detail/-/publication/5207e44d-a6a4-4c9d-badc-19bd8004e813/language-pl (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Geszprych, M. Wpływ regulacji unijnych na kształtowanie gospodarki leśnej w lasach prywatnych w prawie polskim. Kwart. Prawa Publicznego 2008, 8, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kalicka-Mikołajczyk, A. Ochrona lasów w prawie Unii Europejskiej (Forest protection in the European Union). Leśne Pr. Badaw./For. Res. Pap. 2019, 80, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazdinis, M.; Angelstam, P.; Pülzl, H. Towards sustainable forest management in the European Union through polycentric forest governance and an integrated landscape approach. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśkiewicz, K. Realizacja zrównoważonej gospodarki leśnej w wymiarze lokalnym, regionalnym i globalnym—Wybrane aspekty prawne. Przegląd Prawa Rolnego 2018, 22, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubareka, S.; Barredo, J.I.; Giuntoli, J.; Grassi, G.; Migliavacca, M.; Robert, N.; Vizzarri, M. The role of scientists in EU forest-related policy in the Green Deal Era. One Earth 2021, 5, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomina, J.; Pülzl, H. How are forests framed? An analysis of EU forest policy. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 127, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjärstig, T.; Keskitalo, E.C. How to Influence Forest-Related Issues in the European Union? Preferred Strategies among Swedish Forest Industry. Forests 2013, 4, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaba, J.; Jednoralski, G. Polityka leśna i jej wpływ na zmianę użytkowania lasu. Stud. Mater. CEPL Rogowie 2014, 16, 110–117. Available online: https://agro.icm.edu.pl/agro/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-ef5de41d-408d-436a-8843-076428f93ff8/c/Oktaba_Jednoralski.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Pecurul-Botines, M.; Secco, L.; Bouriaud, L.; Giurca, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Brukas, V.; Hoogstra-Klein, M.; Konczal, A.; Marcinekova, L.; Niedzialkowski, K.; et al. Meeting the European Union’s Forest Strategy Goals: A Comparative European Assessment, From Science to Policy; European Forest Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2023; Volume 15, pp. 6–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A.; Wolicka-Posiadała, M. Development of European Union policy on forests and forestry before European Green Deal. Sylwan 2024, 168, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrektywa Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2018/2001 z Dnia 11 Grudnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Promowania Stosowania Energii ze Źródeł Odnawialnych. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L2001&from=ES (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Rady (WE) NR 2012/2002 z Dnia 11 Listopada 2002 r. Ustanawiające Fundusz Solidarności Unii Europejskiej. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02002R2012-20200401 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2021/783 z Dnia 29 Kwietnia 2021 r. Ustanawiające Program Działań na Rzecz Środowiska i Klimatu (LIFE) i Uchylające Rozporządzenie (UE) nr 1293/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R0783&print=true (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2018/841 z Dnia 30 Maja 2018 r. w Sprawie Włączenia Emisji i Pochłaniania Gazów Cieplarnianych w Wyniku Działalności Związanej z Użytkowaniem Gruntów, Zmianą Użytkowania Gruntów i Leśnictwem do Ram Polityki Klimatyczno-Energetycznej do Roku 2030 i Zmieniające Rozporządzenie UE nr 529/2013 (UE). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R0841 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2020/852 z Dnia 18 Czerwca 2020 r. w Sprawie Ustanowienia Ram Ułatwiających Zrównoważone Inwestycje, Zmieniające Rozporządzenie (UE) 2019/2088. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32020R0852 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2023/1115 z Dnia 31 Maja 2023 r. w Sprawie Udostępniania na Rynku Unijnym i Wywozu z Unii Niektórych Towarów i Produktów Związanych z Wylesianiem i Degradacja Lasów Oraz Uchylenia Rozporządzenia (UE) 995/2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R1115 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a Forestry Strategy for the European Union on a Forestry Strategy for the European Union. COM (1998) 649 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:51998DC0649 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Aggestam, F.; Pülzl, H. Coordinating the Uncoordinated: The EU Forest Strategy. Forests 2018, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowa Strategia Leśna UE 2030 z Dnia 16.07.2021 r. COM (2021) 572 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0572 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Komunikat Komisji do Parlamentu Europejskiego, Rady, Europejskiego Komitetu Ekonomiczno-Społecznego i Komitetu Regionów. Unijna strategia na rzecz bioróżnorodności 2030. Przywracanie przyrody do naszego życia. (COM (2020) 380 Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=LEGISSUM:4591047 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lier, M.; Köhl, M.; Korhonen, K.T.; Linser, S.; Prins, K.; Talarczyk, A. The New EU Forest Strategy for 2030: A New Understanding of Sustainable Forest Management? Forests 2022, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowa Strategia Leśna UE na Rzecz Lasów i Sektora Leśno-Drzewnego. COM (2013) 0659 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52013DC0659 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Gordeeva, E.; Weber, N.; Wolfslehner, B. The New EU Forest Strategy for 2030—An Analysis of Major Interests. Forests 2022, 13, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.V.; Kolinjivadi, V.; Ferrando, T.; Roy, B.; Herrera, H.; Vecchione Gonçalves, M.; Van Hecken, G. The “Greening” of Empire: The European Green Deal as the EU first agenda. Political Geogr. 2023, 105, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, A. Uregulowania prawne podjęte w celu realizacji założeń Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu. Perspektywa Polska. Intercathedra 2021, 47, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M. Green Deal, Green Growth and Green Economy as a Means of Support for Attaining the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, E.V. Protecting forests or saving trees? The EU’s regulatory approach to global deforestation. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Saarinen, N.; Saarikoski, H.; Leskinen, L.A.; Hujala, T.; Tikkanen, J. Stakeholder perspectives about proper participation for Regional Forest Programmes in Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L.; D’Amato, D.; Giurca, A.; Hurmekoski, E. Synergies and trade-offs in the European forest bioeconomy research: State of the art and the way forward. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 163, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, B.T. Sawing the Forest for its Trees: An analysis of the discussions regarding the UE Forest Strategy for 2030 in Sweden. Master’s Thesis, MA Programme Euroculture, Palacký University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2022; 80p. Available online: https://theses.cz/id/oudwvz/?lang=en;zoomy_is=1 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Köhl, M.; Linser, S.; Prins, K.; Talarczyk, A. The EU climate package “Fit for 55”—A double-edged sword for Europeans and their forests and timber industry. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 132, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N. Participation or involvement? Development of forest strategies on national and sub-national level in Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, I.; Pülzl, H.; Secco, L.; Sergent, A.; Kleinschmit, D. Research trends: Orchestrating forest policy-making: Involvement of scientists and stakeholders in political processes. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwestri, R.C.; Hájek, M.; Šodková, M.; Sane, M.; Kašpar, J. Bioeconomy in the National Forest Strategy: A Comparison Study in Germany and the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, K.B.; Söderberg, C.; Lukina, N.; Tebenkova, D.; Pecurul, M.; Pülzl, H.; Sotirov, M.; Widmark, C. Clash or concert in European forests? Integration and coherence of forest ecosystem service-related national policies. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicoya, A.T.; Poschenrieder, W.; Blattert, C.; Eyvindson, K.; Hartikainen, M.; Burgas, D.; Mönkkönen, M.; Uhl, E.; Vergarechea, M.; Pretzsch, H. Sectoral policies as drivers of forest management and ecosystems services: A case study in Bavaria, Germany. Land Use Policy 2023, 130, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis-Jakubowicz, P.; Dzięciołowski, R.; Szujecki, A.; Zajączkowski, S. Harmonizacja prawa leśnego. Część I. Porównanie prawa Unii Europejskiej i prawa polskiego w zakresie określonych aspektów leśnictwa.(Forest law harmonization. Part I. A comparison of the EU and Polish legal regulations concerning the selected aspects of forestry). Sylwan 2001, 6, 5–16. Available online: https://agro.icm.edu.pl/agro/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-article-21315d15-294f-456f-878f-48da4f3dbed4/c/SYLWAN_r.2001_t.145_nr.6_str.5-20.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Blattert, C.; Mönkkönen, M.; Burgas, D.; Di Fulvio, F.; Caicoya, A.T.; Vergarechea, M.; Klein, J.; Hartikainen, M.; Antón-Fernández, C.; Astrup, R.; et al. Climate targets in European timber-producing countries conflict with goals on forest ecosystem services and biodiversity. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis-Jakubowicz, P. Teoretyczne podstawy i realizacja idei zrównoważonego rozwoju w leśnictwie. (Theoretical Basis and Implementation of the Idea of Sustainable Development in Forestry). Probl. Ekorozwoju-Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 6, 101–106. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-BPL2-0028-0070 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Kaliszewski, A.; Gil, W. Cele i priorytety “Polityki leśnej państwa” w świetle porozumień procesu Forest Europe (dawniej MCPFE) (Goals and priorities of the National Forest Policy in the light of the Forest Europe (formerly MCPFE) commitments). Sylwan 2017, 161, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozporządzenie Delegowane Komisji (UE) 2021/2139 z Dnia 4 Czerwca 2021 r. Uzupełniające Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2020/852 Poprzez Ustanowienie Technicznych Kryteriów Kwalifikacji Służących Określeniu Warunków, na Jakich Dana Działalność Gospodarcza, Kwalifikuje Się Jako Wnosząca Istotny Wkład w Łagodzenie Zmian Klimatu Lub Adaptację do Zmian Klimatu, a Także Określeniu czy Działalność Nie Wyrządza Poważnych Szkód Względem Żadnego z Pozostałych Celów Środowiskowych. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R2139 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on the New Forest Strategy for 2030. General Secretariat of the Council. Brussels ST-13537-2021 INIT, 10. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13537-2021-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Pelli, P.; Aggestam, F.; Weiss, G.; Inhaizer, H.; Keenleyside, C.; Gantioler, S.; Boglio, D.; Poláková, J. Ex-Post Evaluation of the EU Forest Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; pp. 2–144. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274068208_Ex-post_Evaluation_of_the_EU_Forest_Action_Plan/link/5513d9cf0cf2eda0df302ec2/download (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, T.; Borkowski, P. Perspektywy Polskiego Leśnictwa w kontekście Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu; Referat z Sesji Naukowej pt. “Leśnictwo przyszłości” z Okazji 121 Zjazdu Polskiego Towarzystwa Leśnego w Starych Jabłonkach. Stare Jabłonki; Polskie Towarzystwo Leśne: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; pp. 23–50. Available online: http://www.ptl.pl/dokumenty/zjazdy_krajowe/121_zjazd_stare_jablonki/2_zawila_niedzwiecki_perspektywy_polskiego_lesnictwa_w_kontekscie_europejskiego_zielonego_ladu.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1997 r. Dz. U. 1997, Nr 78 Poz. 483. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19970780483 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 27 Kwietnia 2001 r. Prawo Ochrony Środowiska. Dz. U. 2001 Nr 62 Poz. 627. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20010620627 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 6 Lipca 2001 r. o Zachowaniu Narodowego Charakteru Strategicznych Zasobów Naturalnych Kraju. Dz. U. 2001 Nr 97 Poz. 1051. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20010971051 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 16 Kwietnia 2004 r. o Ochronie Przyrody. Dz. U. 2004 Nr 92 Poz. 880. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20040920880 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rakoczy, B. Gospodarka Leśna i Trwale Zrównoważona Gospodarka Leśna w Prawie Polskim; Wydawnictwo Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 9–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zamelski, P. Zasady gospodarki leśnej w kontekście troski o dobro wspólne i zdrowie publiczne w Polsce. (Principles of forest management in the context of concern for the common welfare and public health in Poland). Sylwan 2018, 162, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, T.; Zięba, W. Wybrane aspekty zrównoważonego użytkowania lasu w nawiązaniu do programu zrównoważonego rozwoju—Przykład Polski. Sylwan 2018, 162, 469–478. Available online: https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/986663.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Instrukcja Urządzania Lasu; Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 15. Available online: https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/publikacje/copy_of_gospodarka-lesna/urzadzanie/iul/instrukcja-urzadzenia-lasu-2011 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Zasady Hodowli Lasu; Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; p. 8. Available online: https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/publikacje/copy_of_gospodarka-lesna/hodowla/zasady-hodowli-lasu-dokument-w-opracowaniu/@@download/file/Zasady-hodowli-lasu.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny Urząd Statystyczny w Białymstoku; Urząd Statystyczny w Białymstoku: Warsaw, Poland; Białystok, Poland, 2024; p. 27. Available online: https://bialystok.stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- León, R.; Bougas, L.; Aggestam, K.; Pülzl, H.; Zoboli, E.; Ravet, J.; Griniecee, E.; Varmeer, J.; Maroullis, N.; Ettwein, F. An Assessment of the Cumulative Cost Impacts of Specified EU Legislation and Policies on EU Forest-Based Industries; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0271b2a0-40b7-11ea-9099-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Lee, H.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Patacca, M.; Seo, B.; Winkler, K.; Rounsevell, M. Three billion new trees in the EU’s biodiversity strategy: Low ambition, but better environmental outcomes? Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 034020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowska, L.; Janiszewska, D.A. Zróżnicowanie funkcji lasów w krajach Unii Europejskiej. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Warszawa Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2016, 16, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport o Stanie Lasów w Polsce; Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; p. 44. Available online: https://www.bdl.lasy.gov.pl/portal/Media/Default/Publikacje/raport_o_stanie_lasow_2022.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Artene, A.E.; Cioca, L.; Domil, A.E.; Ivascu, L.; Burca, V.; Bogdan, O. The Macroeconomic Implications of the Transition of the Forestry Industry towards Bioeconomy. Forests 2022, 13, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, R.; Zielińska-Szczepkowska, J.; Zielińska, A. Rozwój obszarów wiejskich w kontekście zrównoważonej gospodarki leśnej na przykładzie Regionalnej Dyrekcji Lasów Państwowych (RDLP) Olsztyn. Ekon. XXI Wieku 2016, 9, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleyimu, O.I.; Agbeja, B.O.; Akinyemi, O. State of forest in regeneration Southwest Nigeria. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 3381–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupska, A.; Zawadzka, A. Ocena wielofunkcyjnej gospodarki leśnej w Polsce na tle wybranych krajów Unii Europejskiej. Agron. Sci. 2022, 77, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka-Fijorek, E. Rola leśnictwa w tworzeniu produktu krajowego brutto. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Warszawa 2016, 16, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocek, A. Wielofunkcyjność gospodarki leśnej-dylematy ekonomiczne (Multi-functionality of forest management-economic dilemmas). Sylwan 2005, 6, 3–16. Available online: http://agro.icm.edu.pl/agro/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-article-486a35ff-1665-4584-9fc4-f33d7661ba55/c/3.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Raihan, A. Sustainable Development in Europe: A Review of the Forestry Sector’s Social, Environmental and Economic Dynamics. Glob. Sustain. Res. 2023, 2, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kożuch, A.; Adamowicz, K. Wpływ kosztów realizacji pozaprodukcyjnych funkcji lasu na sytuację ekonomiczną nadleśnictw Regionalnej Dyrekcji Lasów Państwowych w Krakowie (Effect of costs incurred on the development of non-productive forest functions on the economic situation in forest districts in the Regional Directorate of the State Forests in Kraków). Sywlan 2016, 160, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołos, P. Społeczne i ekonomiczne aspekty pozaprodukcyjnych funkcji lasu i gospodarki leśnej-wyniki badań opinii społecznej. Prace Instytutu Badawczego Leśnictwa. Rozprawy i monografie. Sękocin Stary 2018, 22, 187–188. Available online: https://bibliotekanauki.pl/books/2022398.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Stubenrauch, J.; Garske, B. Forest protection in the EU’s renewable energy directive and nature conservation legislation in light of the climate and biodiversity crisis—Identifying legal shortcomings and solutions. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 153, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B. Konsekwencje Objęcia Ochroną Ścisłą Znacznych Obszarów Leśnych Polski (Wdrożenie Jednego z Celów Unijnej Strategii na Rzecz Bioróżnorodności do 2030 Roku-Objęcie ścisłą Ochroną 10% Obszarów Lądowych, w Tym Wszystkich Pozostałych w UE Lasów Pierwotnych i Starodrzewów, ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Zagrożenia Spowodowanego Zmianami Klimatycznymi oraz Niekorzystnymi Zmianami Sukcesyjnymi Zbiorowisk Leśnych; Ekspertyza SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; p. 9. Available online: https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/informacje/publikacje/informacje-statystyczne-i-raporty/ekspertyzy-okreslajace-skutki-wdrozenia-unijnej-strategii-na-rzecz-bioroznorodnosci-do-2030-r/konsekwencje-objecia-ochrona-scisla-zbiorowiska-lesne-prof-b-brzeziecki.pdf/@@download/file/Konsekwencje%20obj%C4%99cia%20ochron%C4%85%20%C5%9Bcis%C5%82%C4%85%20zbiorowiska%20le%C5%9Bne%20-%20prof.%20B.%20Brzeziecki.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Wyrembak, J.G. Istota i status konstytucyjnej zasady zrównoważonego rozwoju (według orzecznictwa Trybunału Konstytucyjnego). Przegląd Prawa Konst. 2021, 5, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szramka, H.; Adamowicz, K. Forest development and conservation policy in Poland. Folia For. Pol. Ser. A For. 2020, 62, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A. Cele polityki leśnej w Polsce w świetle aktualnych priorytetów leśnictwa w Europie. Część 4. (Forest policy goals in Poland in light of the current forestry aims in Europe. Part 4. Trends in forest policy of selected European countries). Leśne Pr. Badaw. 2018, 79, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalis-Jakubowicz, P. Polityka leśna a przyszłość lasów i leśnictwa (Forest policy and the future of forests and forestry). Sylwan 2020, 164, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykowski, K. Pojęcie i Zadania Wielofunkcyjnej Gospodarki Leśnej; Instytut Badawczy Leśnictwa: Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2014; p. 8. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/xx/document/view/22442338/pojecie-i-zadania-wielofunkcyjnej-gospodarki-lesnej-instytut- (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Bun, R.; Marland, G.; Oda, T.; See, L.; Puliafito, E.; Nahorski, Z.; Jonas, M.; Kovalyshyn, V.; Ialongo, I.; Yashchun, O.; et al. Tracking unaccounted greenhouse gas emissions due the war in Ukraine since 2022. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lööf, H.; Stephan, A. The Impact of the Russian-Ukrainian War on Europe’s Forest-Based Bioeconomy. Vierteljahrsh. Wirtsch. 2022, 91, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saktiawan, B.; Toro, M.J.S.; Saputro, N. The impact of the Russia-Ukrainian war on green energy financing in Europe. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1114, 012066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Miceikienė, A. Contribution of the European Bioeconomy Strategy to the Green Deal Policy: Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing These Policies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpak, K. Polityka Klimatyczna Unii Europejskiej w Perspektywie 2050 Roku; W: J. Gajewski i Wojciech Paprocki (red), Polityka Klimatyczna i jej Realizacja w Pierwszej Połowie XXI Wieku; Publikacja Europejskiego Kongresu Klimatycznego: Sopot, Poland, 2020; pp. 35–50. Available online: https://www.efcongress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Klimat_internet-zmniejszony.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Winkel, G.; Lovrić, M.; Muys, B.; Katila, P.; Lundhede, T.; Pecurul, M.; Pettenella, D.; Pipart, N.; Plieninger, T.; Prokofieva, I.; et al. Governing Europe’s forests for multiple ecosystems services: Opportiunities, challenges and policy options. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 145, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggestam, F.; Püzl, H. Downloading Europe: A Regional Comparison in the Uptake of the EU Forest Action Plan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, G.; Trein, F. Policy Integration as a Political Process. Policy Sci. 2023, 56, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuurs, G.J.; Verweij, P.; Eupenl, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Pülzl, H.; Hendriks, K. Next-generation information to support a sustainable course for European forests. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, W.; Sarniak, L.; Wanat, L.; Wieruszewski, M. Green Deal: Opportunities and threats for the forest- and wood-based sector in Poland. In Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific Conference WoodEMA 2022, Trnava, Slovakia, 8–10 June 2022; pp. 211–214. Available online: https://www.woodema.org/proceedings/WoodEMA_2022_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

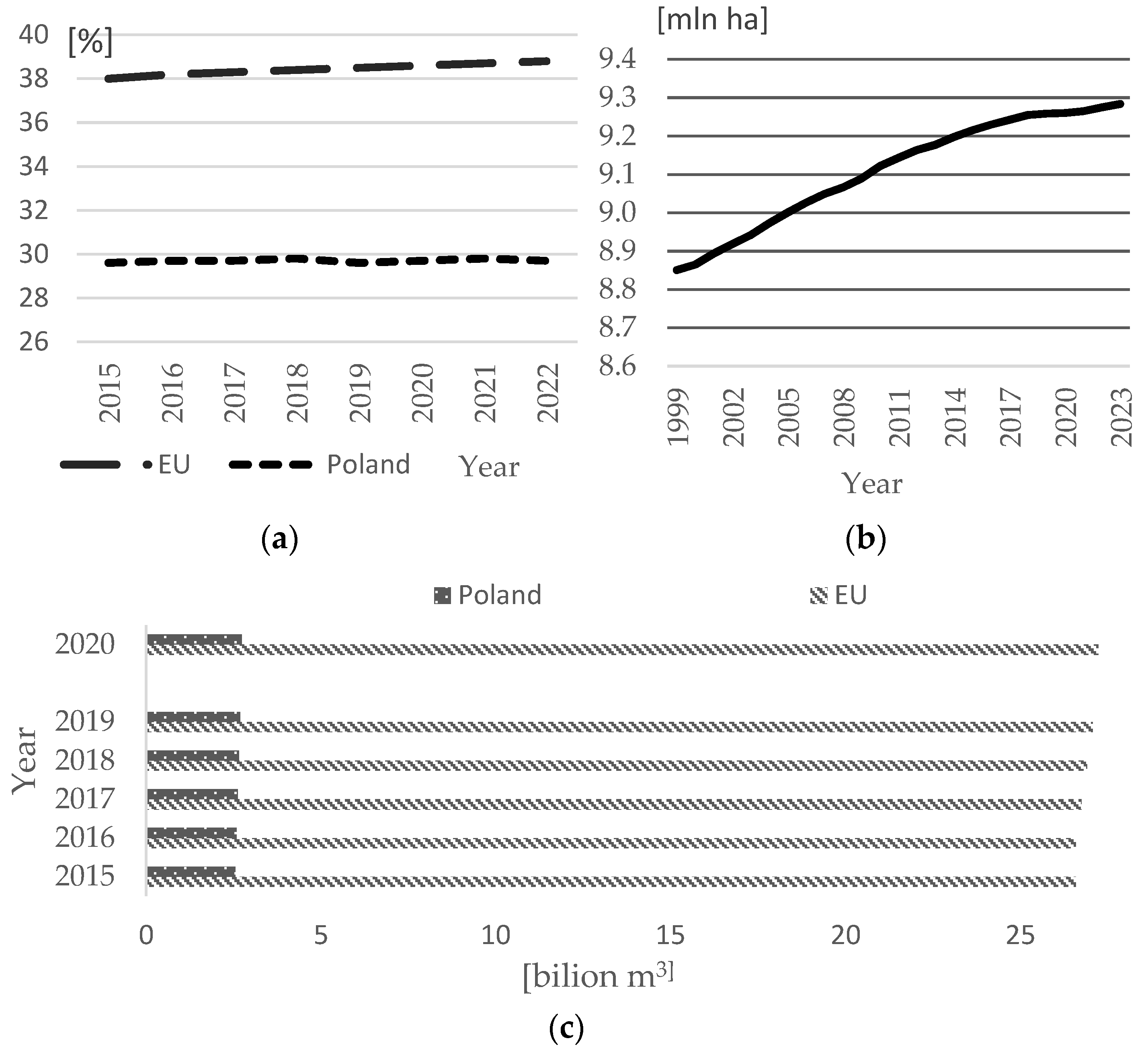

| Category | EU | Poland |

|---|---|---|

| Forest area | About 160 million ha (39% of the EU area) | About 9.4 million ha (30% of the country’s area) |

| Area of Natura 2000 areas | 18% of the EU area | 20% of the country’s area |

| Area of National Parks | 3% of the EU area | 1% of the country’s area |

| Area of nature reserves | 4% of the EU area | 0.6% of the country’s area |

| Protection of primeval and old-growth forests | Less than 0.5% of the EU area | 3% of the country’s area |

| Protective measures | Conservation of biodiversity, protection of old and primeval forests, and sustainable forest management. | Striving to preserve biodiversity and sustainable forest management. |

| Meeting the goals in quantitative and qualitative participation | Expanding the network of protected areas, including Natura 2000, and implementing actions to improve the health of forest ecosystems, with an emphasis on preserving biodiversity and protecting old, primeval forests. | Development of the Natura 2000 network, expansion of the area of national parks and nature reserves, as well as protection of old and primeval forests while ensuring sustainable forest management and biodiversity. |

| Environmental protection investments of total economy | 0.40% | 0.50% |

| Percentage of environmental taxes in total revenue from taxes and social security contributions | 5.30% | 8.12% |

| Net greenhouse gas emissions of the Land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sector | Year 2019 (−240 983 t) Year 2020 (−240 779 t) Year 2021 (−240 885 t) Year 2022 (−236 401 t) | Year 2019 (−22 561 t) Year 2020 (−23 330 t) Year 2021 (−23 916 t) Year 2022 (−35 644 t) |

| Contribution to the international USD 100 billion commitment on climate-related expenses (million EUR) | Year 2019 16 205, 77 Year 2020 18 103, 89 Year 2021 17 977, 97 Year 2022 21 920,86 | Year 2019 12.88 Year 2020 22.49 Year 2021 8.44 Year 2022 19.45 |

| Protected areas (mln km2) | Year 2021 1076 Year 2022 1080 | Year 2021 0.123 Year 2022 0.123 |

| New EU Forest Strategy 2030 | State Forest Policy |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Reference to SFP |

| Supporting the socio-economic functions of forests for thriving rural areas and boosting a forest-based bioeconomy within the limits of sustainable development. | Yes |

| Supporting a sustainable forest bioeconomy for sustainable wood products. | Objective 8b—strengthening the productive function of forests. |

| Ensuring the sustainable use of wood-based resources for energy use. | Objective 2—ensuring the sustainability of forests and their multifunctionality. Objective 8b—strengthening the productive function of forests. |

| Promoting a bioeconomy based on non-timber forest products, including ecotourism. | Objective 5—improving the condition and protection of forests. Objective 6—promoting and protecting biodiversity throughout the entire forest management and management process. Objective 8b—strengthening production functions. Objective 8c—strengthening the social functions of forests. |

| Developing skills and empowering citizens in a sustainable forest-based bioeconomy. | Objective 5—improving the condition and protection of forests. Objective 8 c—strengthening the social functions of forests. |

| Protecting, restoring, and expanding EU forests to combat climate change, reverse biodiversity loss, and ensure resilient and multifunctional forest ecosystems. | Yes |

| Protecting the EU’s last remaining primary forests and old-growth forests. | Objective 6—the need to provide statutory protection for all forests. Objective 8a—strengthening the ecological functions of forests. |

| Ensuring forest restoration and strengthening sustainable forest management to adapt to climate change and increase forest resilience. | Objective 5—improving the condition and protection of forests. Objective 6—promoting and protecting biodiversity throughout the entire forest management and management process. Objective 7—continuation of the forest promotional complexes program. Objective 8b—strengthening the production functions of forests. Objective 8c—strengthening social functions by integrating forestry goals with sustainable development goals. |

| Reforestation and reforestation of biodiversity-rich forests. | Objective 3—increasing forest resources. Objective 4—increasing forest resources. Objective 8a—strengthening all important types of forest functions, especially their ecological functions. |

| Financial incentives for forest owners and managers to improve the quantity and quality of forests in the EU. | Mentioned in the theses—building legal and financial mechanisms encouraging forest owners and managers to invest continuously. Objective 9—the need to establish appropriate legal, economic and organizational bases for owners of private forests. Indicated in the conditions. |

| Strategic forest monitoring, reporting, and data collection. | Mentioned in terms and conditions. |

| A comprehensive research and innovation program to improve knowledge about forests. | Objective 6—theoretical and experimental studies on the new forest model. Objective 8c—ecological and forest social education. Mentioned in terms and conditions. |

| A coherent and inclusive EU forest management framework. | Mentioned in terms and conditions. |

| New EU Forest Strategy 2030 | State Forest Policy | |

|---|---|---|

| NSL goals | Method of achieving the goal. | Method of achieving the goal. |

| 1. Supporting the socio-economic functions of forests for prosperous rural areas and stimulating a forest-based bioeconomy within the limits of sustainable development. | Cascading use of wood, legal regulations enabling access to support systems, and aid funds treating the forest as a CO2 absorber. | Implementation of permanently sustainable forest management, synergy of forestry with the wood industry, and promotion of the use of wood. |

| 2. Protecting, restoring, and expanding forests in the EU to combat climate change, reverse biodiversity loss, and ensure resilient and multifunctional forest ecosystems. | Percentage of land under legal protection, quantification of the number of trees to be planted, promotion of forest ecosystem services, support systems, fees to forest owners, public support, and a certification system. | New models of forest and forest management taking into account its multifunctional role and the legal protection of all forests taking into account primary forests, especially valuable ones (comprehensive approach at the stage of forest management planning) and strengthening its production and social functions, achieving the goal using appropriate economic practices. |

| 3. Strategic monitoring, reporting, and data collection in the field of forests. | Unification of the reporting system, data collection and use of new technologies for data acquisition, forest observation, and covering more private forests with forest management plans. | Extension of competences, BUL, and GL for forests regardless of the form of ownership, traditional monitoring of forests and the functions they perform. |

| 4. A comprehensive research and innovation program to improve knowledge about forests. | Program support, promotion of EGD, information campaign on primary forests and old-growth forests, ecosystem services, research on agroforestry systems and trees outside the forest, technical innovations introduced in rural areas, private investments in the circular economy. | Scientific research on a new forest model, public education, Olympiads, development of educational chambers. |

| 5. A coherent and inclusive EU forest management framework | Updating the management system integrating expert groups. | Public consultations and cooperation with associations, local governments, and social organizations. |

| 6. Intensifying implementation and enforcement of the existing EU acquis | Review of EU legal acts, updating guidelines on the interpretation of regulations for their consistent enforcement in cooperation with member states, promotion of geospatial intelligence, and the role of civil society. | Legal protection of forests of all forms of ownership and improvement of mechanisms and methods for Poland’s compliance with signed international conventions, agreements, and understandings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brożek, J.; Kożuch, A.; Wieruszewski, M.; Adamowicz, K. Verification of the Assumptions of the Polish State Forest Policy in the Context of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062398

Brożek J, Kożuch A, Wieruszewski M, Adamowicz K. Verification of the Assumptions of the Polish State Forest Policy in the Context of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062398

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrożek, Jarosław, Anna Kożuch, Marek Wieruszewski, and Krzysztof Adamowicz. 2025. "Verification of the Assumptions of the Polish State Forest Policy in the Context of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062398

APA StyleBrożek, J., Kożuch, A., Wieruszewski, M., & Adamowicz, K. (2025). Verification of the Assumptions of the Polish State Forest Policy in the Context of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030. Sustainability, 17(6), 2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062398