2.1. Push and Pull Factors as Trigger in Tourism

Motivation factors can vary from person to person and can even change over time, but they often play an important role in the decision to travel [

15]. Thus, the various motivations are what lead tourists to visit a particular destination, determine the adoption of different types of behavior, and the criteria that contribute to the evaluation of the tourist experience [

7]. The designation of push and pull factors, initially studied by Dann [

16] and Crampton [

17], has served as the basis for many studies on motivations. There is currently a consensus among researchers that push and pull factors in tourism influence people’s decisions to travel and their specific choice of destinations [

7]. Push factors in tourism usually refer to conditions intrinsic to the traveler and are related to personal desires, beliefs, interests, and needs [

18]. Push motives include hedonic tourist experiences, such as relaxation, leisure, escapism, seeking adventure and new sensations, or family togetherness [

7]. However, in the context of sustainable tourism, these intrinsic motivations are evolving. Travelers may also be driven by ethical concerns, such as reducing their carbon footprint, engaging in ecotourism, or avoiding overcrowded destinations [

6]. Pull factors in tourism refer to the characteristics and attractions of a given destination that led travelers to visit it [

18]. These factors are fundamental to attracting tourists and can vary greatly from one place to another, depending on the characteristics of each destination [

6]. Pull motives are conditioned by the tourists’ evaluations of the perceived usefulness and attributes of the destination, with the image of the destination being one of the most efficient ways of evaluating these attributes [

6]. Increasingly, these attributes incorporate sustainability-related aspects, such as protected natural areas, responsible tourism infrastructure, and community-based tourism experiences [

18]. This suggests that a tourist’s attitude towards the destination can be a measure of the ability of that destination to attract tourists [

19].

2.2. Emotions Impact on Push and Pull Factors

Emotions are responses to external stimuli based on cognitive evaluations of different experiences [

20]. They function as a barometer with which individuals positively or negatively assess their surroundings [

8]. In the context of tourism, emotions are essential as they influence all phases of the tourist experience and allow visitors to connect with destinations [

21].

There is a close connection between motivations and emotions. The desire to travel is related to the conscious and subconscious, which means that the motives, perception, and subsequent evaluation of experiences are not only rational acts, but involve emotional elements [

7]. Tourist destinations are made up of a vast set of experiential attributes, which allow visitors to have memorable experiences [

22].

Memorable experiences are naturally associated with hedonism, which in turn leads us to positive emotions that involve pleasure and satisfaction with the tourist destination [

23]. However, although tourism activity is based on hedonism and the pursuit of pleasure, the impact of negative emotions on the evaluation of the tourist experience must be considered [

21]. While consumers tend to respond to positive emotions with positive behaviors, negative emotions often result in negative behaviors [

24].

Although positive and negative emotions are, in principle, antagonistic, this does not mean that they cannot be experienced simultaneously in the same event [

25]. That is, in the same event, participants may be faced with mixed emotions and feel happy in a certain situation and dissatisfied in others [

24]. In this sense, emotions related to tourism (positive and negative) play a significant role in the visitors’ motivations, whether they are push factors or pull factors [

8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental and public health concerns became fundamental determinants of travel, shaping both push and pull factors [

26]. As travel restrictions were eased, many travelers began prioritizing destinations with strong sustainability credentials, including those promoting ecotourism, eco-friendly accommodations, and conservation efforts [

27]. Furthermore, push factors evolved to place greater emphasis on well-being, nature-based tourism, and more responsible travel behaviors [

28]. This suggests that the pandemic not only reshaped travel habits in the short term but may have accelerated a long-term shift toward sustainable tourism behaviors.

2.3. Push and Pull Factors in Tourism During and After the Pandemic COVID-19

During the pandemic, factors of health and safety became priorities, creating opportunities for the development of more sustainable forms of tourism (

Table 1). These included valuing less densely populated destinations and those in closer contact with nature, contributing to tourism practices that respect the environment and local communities [

2].

Push and pull factors in tourism are particularly relevant when considering the tourists’ feelings and behaviors during a particular external event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

4]. During the pandemic, the push factors were intensified, as travel was restricted, or even banned, creating a need to travel, to leave one’s place of residence, or even the need to leave for more distant and less affected places due to the fear of contamination [

19]. Travel also became a way of coping with the psychological stress caused by the pandemic [

29]. Regarding the pull factors, some positive feelings were resisted, such as the relief and comfort of reaching less affected destinations, the perceived need to avoid large concentrations of people, and the desire to get more in touch with nature, contributing to new forms of tourism [

30].

Table 1.

Key elements of the push and pull factors, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Key elements of the push and pull factors, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Factors | Push Factors | Pull Factors | Authors |

|---|

| Social | Escapism, psychological stress, travel restrictions creating a need to travel | Positive accessibility, social conditions, political and security conditions in destinations | [19,31,32,33] |

| Cultural | Interest in different cultures, traditions, gastronomy, and languages | Destinations with rich cultural heritage (tangible and intangible), gastronomy | [2,6,18,27] |

| Economic | Financial difficulties due to the pandemic, employment, and income levels | Affordable prices, competitive packages, value for money in destinations | [2,34,35,36] |

| Psychological | Desire for relaxation, break from stress, curiosity, coping with psychological stress of the pandemic | Relief and comfort in destinations, escape from lockdown stress, resilience, and adaptation during travel | [14,19,37,38] |

| Environmental | Desire to escape environmental dangers, seeking nature, health, and well-being needs | Natural resources, unique geological and geographical features, sustainable practices in destinations | [15,18,39,40] |

| Service quality | Seeking personal development, professional reasons, watching/practicing sports | Quality of accommodation, transportation, services, infrastructure, hospitality of residents | [18,41,42,43] |

Doğan et al. [

42] demonstrated that fear of COVID-19 had a significant negative impact on travel intentions, reducing the tourists’ willingness to visit new destinations. According to the authors, trust in the vaccines did not have a significant effect on the relationship between fear and travel intention. This finding suggests that, despite the progress of vaccination campaigns, fear of the disease continued to negatively influence travel decisions. The present study builds upon these findings by analyzing the interaction between push and pull motivational factors and positive and negative emotions before, during, and after the pandemic. Additionally, it provides further evidence on how emotions can influence and modify the motivations that drive tourists to travel, emphasizing their role as key determinants in travel decision-making.

In one study, the positive feelings of being able to travel again, the escape from the stress and monotony of lockdowns, as beneficial psychological stimulus, resilience, and adaptation during the pandemic had an impact when choosing a tourist destination [

19]. In another study, the negative emotions experienced during the pandemic were complex and varied from person to person [

38]. In another study, fear and anxiety limited the intention to travel, while frustration and disappointment were caused by canceled plans, in addition to feelings of guilt for traveling in a context where not traveling was recommended, due to the danger of contamination to the tourists themselves and the potential spread of the virus, as well as feelings of nostalgia and longing, because people may experience nostalgia for past travel experiences, and a longing to return to a sense of normality in tourism [

32]. However, given the impact of the spread of the pandemic, the demand for certain destinations was largely affected, not only by the difficulty in accessing certain destinations, but by the very impediment or conditions required, such as vaccination, negative tests, even the impediment to visiting certain cultural attractions and recreational activities [

33].

The pandemic forced tourists, the tourism sector, and destinations alike to adapt to a new reality characterized by health and safety concerns, but the restrictions implemented after the outbreak have resulted in the development of trends in how people consume tourism, affecting the push and pull factors [

14]. Considering the above, the first hypotheses were derived:

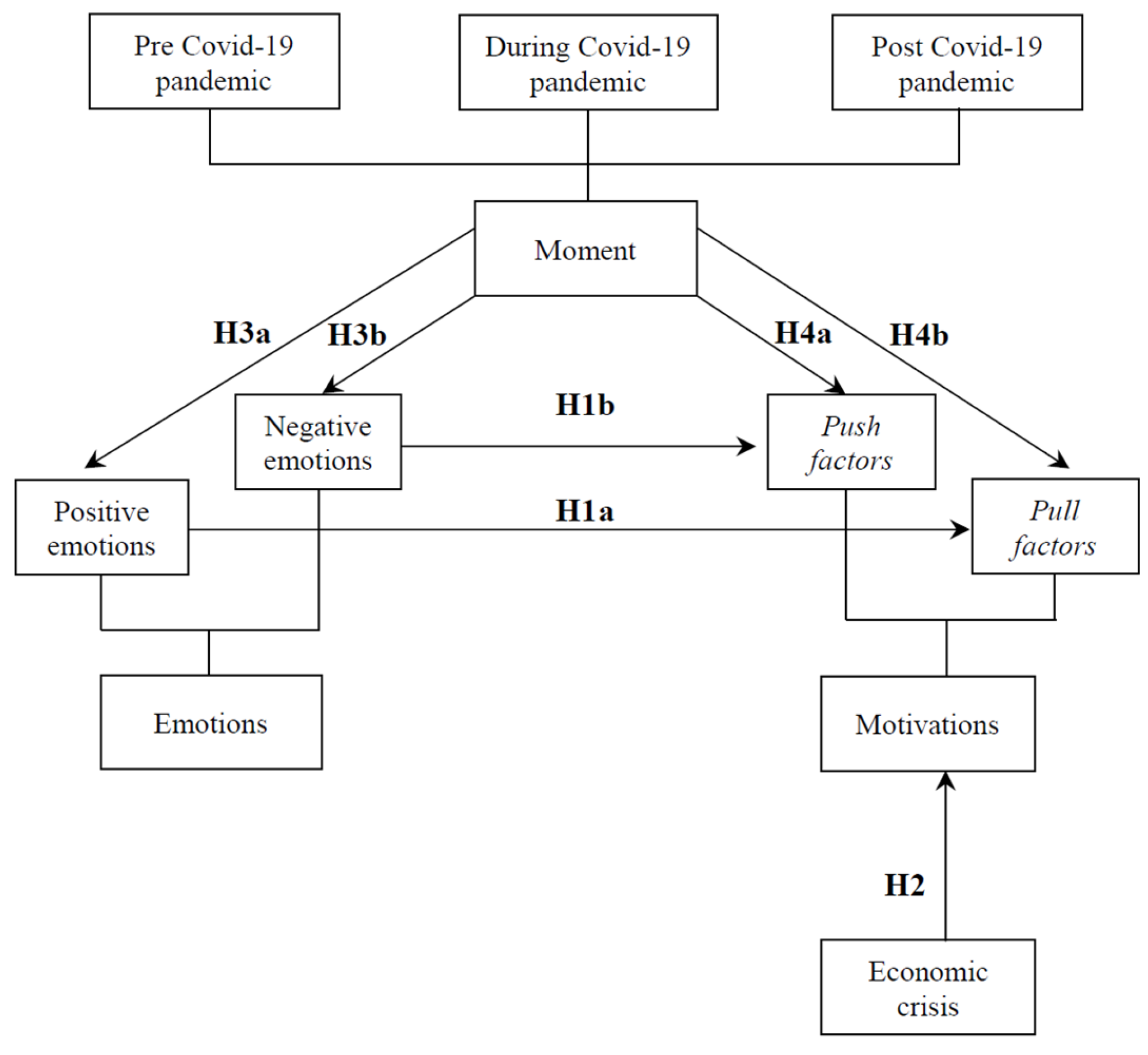

Hypothesis 1: Emotions have an impact on the factors that influence the choice of tourist destination.

Hypothesis 1a: Push factors are negatively influenced by emotions when choosing a tourist destination.

Hypothesis 1b: Pull factors are positively influenced by emotions when choosing a tourist destination.

The economic crisis caused by the pandemic has had profound effects on tourism, encompassing push and pull factors, as well as a complex web of emotions, reshaping travel motivations [

44]. The COVID-19 pandemic economic crisis affected push factors because many individuals and families faced financial difficulties due to job losses or reduced income [

4]. This economic strain decreased their ability to afford travel, as they grappled with more immediate concerns and lacked the emotional or financial resources to plan trips [

35]. In addition, the pandemic not only imposed travel restrictions to contain disease spread but impacted tourism by reducing tourist numbers and driving up prices in destinations [

36]. Importantly, these developments, together with the ensuing economic crisis, significantly influenced the pull factors in the tourism industry [

45]. Under these assumptions, the second hypothesis was outlined:

Hypothesis 2: The economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the motivation to choose a tourist destination.

Before the pandemic, positive emotions included enthusiasm, joy, and happiness (pre-trip), and good memories and a feeling of personal accomplishment (post-trip), depending on when the trip took place [

19]. Negative emotions included anxiety, doubts, and fears related to the trip (pre-trip) and sadness, anger, disappointment, and dissatisfaction (post-trip) [

31]).

As mentioned above, during the pandemic negative emotions were particularly prominent, with fear and social concerns emerging as key factors related to the risk of contagion and the restrictions imposed upon travelers returning to their home countries, including mandatory isolation [

26]. Furthermore, the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic heightened anxiety in the travel decision-making process, leading many tourists to reconsider or postpone their plans. However, positive emotions also played a significant role in shaping travel behavior. Enthusiasm and anticipation for the opportunity to explore new destinations were evident during the pre-travel phase, while post-travel experiences were predominantly characterized by relaxation, personal satisfaction, and a sense of accomplishment. The perception that the trip unfolded as expected contributed to a positive evaluation of the overall tourism experience [

46]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between negative and positive emotions in travel motivation, reinforcing the ambiguity and variability of tourist behavior during the pandemic.

In the post-pandemic period, tourism has changed. More rural and sustainable areas, as well as services more concerned with the preservation and sanitization of spaces, have become more sought after [

28,

47]. Considering all the above, the following hypotheses were developed:

Hypothesis 3: Emotions varied depending on when the data was collected.

Hypothesis 3a: Positive emotions varied depending on when the data was collected.

Hypothesis 3b: Negative emotions varied depending on when the data was collected.

Before the pandemic, pull motivations varied according to individual characteristics, shaped by psychological, social, cultural, financial, and demographic contexts. Meanwhile, push motivations encompassed factors such as leisure, the pursuit of novel experiences, cultural exploration, the desire to escape daily routines, and relaxation [

13]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced an unprecedented shift in these motivational dynamics, as health and safety concerns became primary determinants of travel decisions [

48]. The fear of infection and the imposition of travel restrictions intensified repulsion factors, leading travelers to prioritize destinations perceived as safe and spacious, where close interpersonal contact could be minimized [

49]. As a result, push and pull motivations during the pandemic were largely influenced by the search for low-density environments, contributing to the rise of rural and nature-based tourism as a coping mechanism to alleviate pandemic-related stress [

2].

Regarding the post-pandemic period, more countries, regions, and cities have reopened following widespread vaccination, travel motivations have also begun to change, although not always to the pre-pandemic standards [

14]. Tourists in post-pandemic times have been more avid about the sustainability of the trips taken and health-centered tourism, showing that the change in push and pull motivations is long-term; they now include mental health, outdoor activities, reconnecting with family or friends, and searching for more memorable experiences [

50].

Hence, the temporal evolution of tourism motivation allows us to consider how external crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can radically change the classical model of push and pull factors. In the period before the onset of the pandemic, the motivational factors were mostly aimed at leisure and adventure [

7]. Thus, the following hypotheses are presented:

Hypothesis 4: Motivations to travel differed significantly depending on when the data was collected.

Hypothesis 4a: Push factors differed significantly depending on when the data was collected.

Hypothesis 4b: Pull factors differed significantly depending on when the data was collected.

Figure 1 illustrates the connections between the variables.