Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Methodology

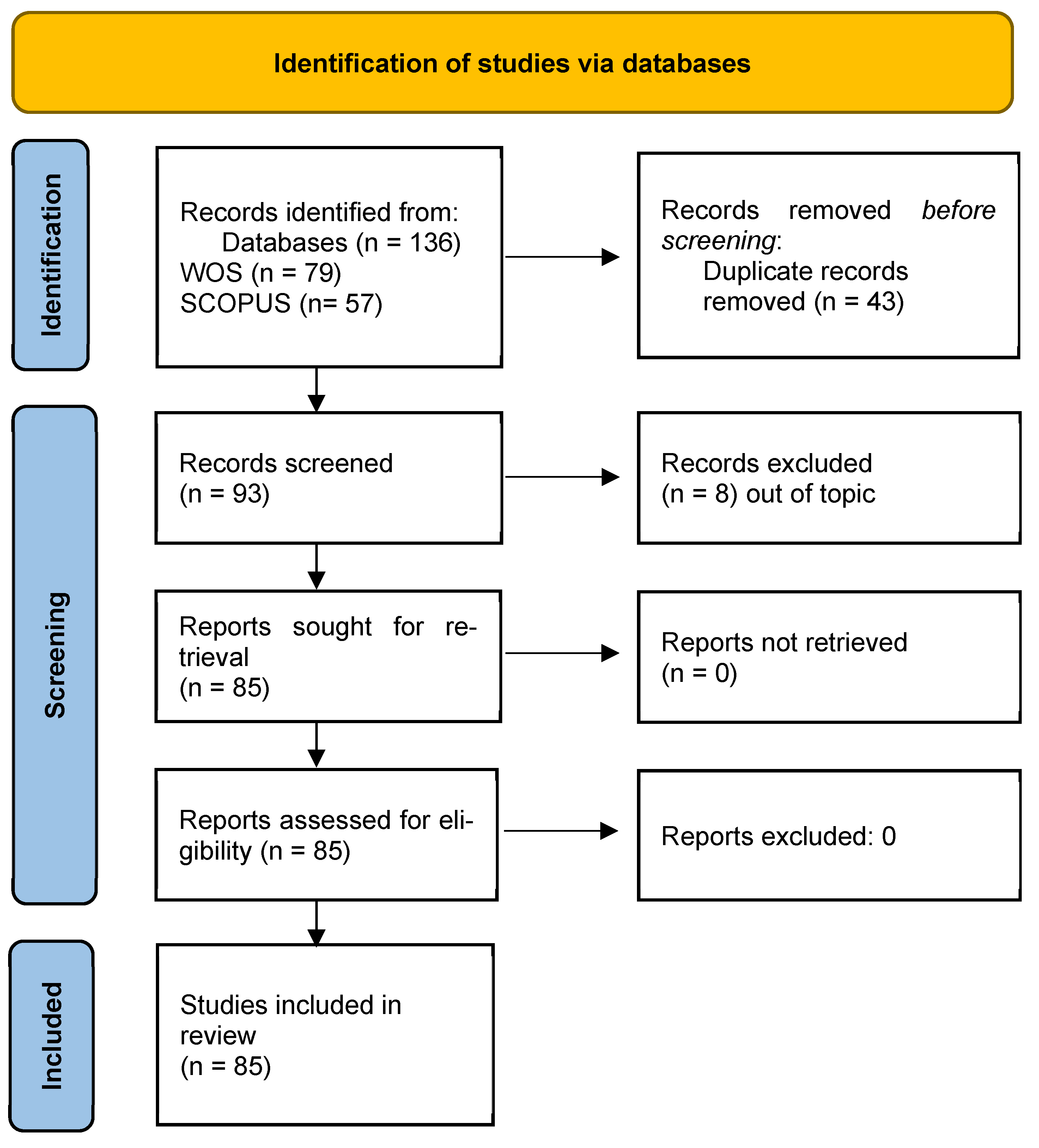

- Identification—Records were retrieved from the Web of Science and Scopus databases using targeted keywords.

- Screening—Titles and abstracts were reviewed based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Eligibility Assessment—Full-text articles were evaluated to ensure relevance.

- Final Inclusion—Studies that met all criteria were incorporated into the review.

- “sustainable food consumption” AND “motivations*”;

- “sustainable food consumption” AND “barriers*”;

- “sustainable food consumption” AND “technology”;

- “corporate responsibility” AND “sustainable food systems”.

- Abstract clarity (+1 point);

- DOI availability (+1 point);

- Peer-review status (+1 point);

- Clear methodology (+1 point);

- Clearly defined objectives (+1 point).

- Identifying key topics of interest;

- Analyzing temporal trends;

- Exploring thematic co-occurrences.

- Literature organization in Zotero

- ○

- Motivations (n = 26)—Consumer drivers and incentives;

- ○

- Barriers (n = 36)—Obstacles and limitations;

- ○

- Technology (n = 15)—Digital solutions and innovations;

- ○

- Corporate Initiatives (n = 8)—Business strategies and programs;

- ○

- Computational Analysis (Adobe AI and Python-Based Pipeline).

- Data extraction via Zotero API

- ○

- Automated text and pattern analysis;

- ○

- Statistical trend identification and relationship mapping;

- ○

- Generation of visual representations.

- Results, Visualization, and Interpretation

- ○

- Thematic mapping to illustrate key research themes;

- ○

- Temporal trend visualization to track changes over time;

- ○

- Comparative analysis across study collections;

- ○

- Cross-theme pattern identification.

4. Results

4.1. Motivation in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.1.1. Recurring and Co-Occurring Categories of Motivation in Sustainable Food Consumption

| Theme | Description | Co-Occurring Themes | Examples from Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Concerns | Perceived health benefits, safety, and nutrition | Quality, safety, nutritional value | [38,39,40,41] |

| Environmental Awareness | Desire to reduce environmental footprint | Ethical beliefs, support for local economies | [38,39,42,43] |

| Ethical and Moral Beliefs | Concerns about animal welfare, social justice | Social norms, altruistic values | [38,44,45,46] |

| Social and Personal Norms | Influence of societal expectations and personal values | Social influence, community connection | [38,43,44,48] |

| Taste and Quality | Sensory appeal and perceived quality of sustainable food | Health benefits, naturalness | [38,39,42,49] |

| Support for Local Economies | Desire to support local farmers and economies | Environmental concerns, social Responsibility | [42,49,50] |

| Knowledge and Awareness | Understanding the impact of food choices on sustainability | Education, personal experiences | [38,46] |

| Religious and Cultural Factors | Influence of religious beliefs and cultural practices | Health, ethical considerations | [38,41] |

| Emotional and Psychological Fulfillment | Emotional satisfaction and sense of accomplishment | Personal well-being, social connections | [40,50] |

| Economic and Practical Considerations | Affordability and practical aspects of purchasing sustainable products | Perceived behavioral control, economic status | [43,46] |

4.1.2. Temporal Analysis of the Evolutions of Various Motivations

4.1.3. An In-Depth Examination of Drivers Behind Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2. Barriers in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2.1. Recurring Categories of Barriers in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2.2. Temporal Analysis of the Evolutions of Various Barriers

4.2.3. In-Depth Analysis of Barriers to Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3. Technologies in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3.1. Recurring Themes and Categories of Technologies in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3.2. Temporal Evolution of Technology Categories in Sustainable Consumption

4.3.3. In-Depth Analysis of Sustainable Food Consumption Technologies

4.4. Corporative Initiatives in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.4.1. Recurring Themes and Categories of Corporate Initiatives in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.4.2. Temporal Evolution of Corporate Initiatives Categories in Sustainable Consumption

4.4.3. In-Depth Analysis of Sustainable Food Corporate Initiatives

4.5. Bibliometric Analysis and Research Clusters

5. Discussion

- Subsidize sustainable food options to make them affordable;

- Expand accessibility by ensuring mainstream market availability;

- Enforce transparency in food labeling to prevent green washing;

- Leverage technology to empower informed consumer choices;

- Hold corporations accountable through global regulatory frameworks.

6. Contributions, Limits of the Study and Recommendations

6.1. Contributions of the Study

- Longitudinal impact of interventions to track behavioral shifts over time;

- The role of digital solutions and AI in overcoming awareness and accessibility barriers;

- Cultural adaptation of sustainability strategies to ensure their effectiveness across diverse populations.

- Role of AI and automation in driving corporate sustainability;

- How can digital solutions enhance consumer engagement in sustainability?;

- Longitudinal impact of corporate policies on consumer behavior.

6.2. Methodological Limitations of the Analysis

6.3. Future Research Direction and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, M.; Tilman, D. Comparative Analysis of Environmental Impacts of Agricultural Production Systems, Agricultural Input Efficiency, and Food Choice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 064016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and Valuation of the Health and Climate Change Cobenefits of Dietary Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Snoek, H.M.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Bouwman, E.P. Sustainable Food Choice Motives: The Development and Cross-Country Validation of the Sustainable Food Choice Questionnaire (SUS-FCQ). Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, M.H.C.; Smit, E.S.; De Wildt, K.; Karvonen, S.-G.; Van Der Plas, D.; Van Der Laan, L.N. Stimulating Sustainable Food Choices Using Virtual Reality: Taking an Environmental vs Health Communication Perspective on Enhancing Response Efficacy Beliefs. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozelli Sabio, R.; Spers, E.E. Consumers’ Expectations on Transparency of Sustainable Food Chains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 853692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Ritz, C.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Intention to Consume Plant-Based Yogurt Alternatives. Foods 2021, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Long, S.; Gao, J.; Ali, K.A.M. The Effect of Environmental Values, Beliefs, and Norms on Social Entrepreneurial Intentions among Chinese University Students. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Combining the VBN Model and the TPB Model to Explore Consumer’s Consumption Intention of Local Organic Foods: An Abstract. In Celebrating the Past and Future of Marketing and Discovery with Social Impact; Allen, J., Jochims, B., Wu, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 535–536. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-85702-042-0. [Google Scholar]

- Monterrosa, E.C.; Frongillo, E.A.; Drewnowski, A.; de Pee, S.; Vandevijvere, S. Sociocultural Influences on Food Choices and Implications for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 59S–73S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassini, L.; Staffieri, S.; Cavagnaro, E. Local Food Consumption and Practice Theory: A Case Study on Guests’ Motivations and Understanding. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 11, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; p. 293. ISBN 978-0-300-12223-7. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, B.; Jafarian, A.; Abdi, Z. Nudging towards Sustainability: A Comprehensive Review of Behavioral Approaches to Eco-Friendly Choice. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HawkPartners. Subtle Shifts: Using Nudging to Alter Consumer Behavior. Available online: https://hawkpartners.com/behavioral-economics/subtle-shifts-using-nudging-to-alter-consumer-behavior/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Li, P.; Lin, I.-K.; Chen, H.-S. Low Carbon Sustainable Diet Choices—An Analysis of the Driving Factors behind Plant-Based Egg Purchasing Behavior. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; Shwom, R.; Caggiano, H.; Slattery, J.; Cuite, C.; Schelly, C.; Halvorsen, K.E.; Lytle, W. Habitual Food, Energy, and Water Consumption Behaviors among Adults in the United States: Comparing Models of Values, Norms, and Identity. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 85, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.L. How Green Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations Interact, Balance and Imbalance with Each Other to Trigger Green Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Polynomial Regression with Response Surface Analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Dai, X.; Zhang, Y. The Government Subsidy Policies for Organic Agriculture Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, K. Can Climate-Friendly Food Labels Transform Eaters into Environmentalists? Available online: https://foodprint.org/blog/climate-friendly-food/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Reichheld, A.; Peto, J.; Ritthaler, C. Reichheld Research: Consumers’ Sustainability Demands Are Rising. Available online: https://hbr.org/2023/09/research-consumers-sustainability-demands-are-rising (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Sustainability News. Over Half of Consumers Would Boycott Companies Caught Greenwashing. Available online: https://sustainability-news.net/greenwashing/over-half-of-consumers-would-boycott-companies-caught-greenwashing/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Nygaard, A. Is Sustainable Certification’s Ability to Combat Greenwashing Trustworthy? Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1188069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of Consumer Environmental Responsibility on Green Consumption Behavior in China: The Role of Environmental Concern and Price Sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, L.; Chevrier, M.; Zenasni, F. Consistent or Inconsistent? The Effects of Inducing Cognitive Dissonance vs. Cognitive Consonance on the Intention to Engage in pro-Environmental Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 902703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, M. Too Good to Go: Combating Food Waste with Surprise Clearance (15 September 2023). Forthcoming in Management Science. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4573386 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Cao, S.; Xu, H.; Bryceson, K.P. Blockchain Traceability for Sustainability Communication in Food Supply Chains: An Architectural Framework, Design Pathway and Considerations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basa, R. AI in Agriculture: Revolutionizing Precision Farming and Sustainable Crop Management. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 10, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimakopoulos, F.; Vassilakis, C.; Margaris, D.; Kotis, K.; Spiliotopoulos, D. Artificial Intelligence Tools for the Agriculture Value Chain: Status and Prospects. Electronics 2024, 13, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, A.; Spencer, M. Corporate Net Zero Pledges: A Triumph of Private Climate Regulation or More Greenwash? Griffith Law Rev. 2023, 32, 110–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; Gellynck, X.; Slabbinck, H. Do Fair Trade Labels Bias Consumers’ Perceptions of Food Products? A Comparison between a Central Location Test and Home-Use Test. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Bastounis, A.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Stewart, C.; Frie, K.; Tudor, K.; Bianchi, F.; Cartwright, E.; Cook, B.; Rayner, M.; et al. The Effects of Environmental Sustainability Labels on Selection, Purchase, and Consumption of Food and Drink Products: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 891–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Karabagias, I.K. Biodegradable Packaging Materials for Foods Preservation: Sources, Advantages, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2023, 13, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter de Villiers, M.; Cheng, J.; Truter, L. The Shift Towards Plant-Based Lifestyles: Factors Driving Young Consumers’ Decisions to Choose Plant-Based Food Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Verain, M.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable Food Consumption. Product Choice or Curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Baudry, J.; Allès, B.; Péneau, S.; Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Amiot, M.-J.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D. Determinants and Correlats of Consumption of Organically Produced Foods: Results from the BioNutriNet Project. Cah. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 53, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Luomala, H. A Comparison of Motivational Patterns in Sustainable Food Consumption between Pakistan and Finland: Duties or Self-Reliance? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021, 33, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Mostafa, T. Green Consumers’ Behavioral Intention and Loyalty to Use Mobile Organic Food Delivery Applications: The Role of Social Supports, Sustainability Perceptions, and Religious Consciousness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 15953–16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, A.; de Moura, A.; Deliza, R.; Cunha, L. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Q. Predicting Sustainable Food Consumption across Borders Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Sánchez, L.; Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Gamba, M.; Grisotto, G.; Moreno Londoño, A.M.; Mantilla-Uribe, B.P.; Rincón Méndez, A.Y.; Ballesteros, M.; Kopp-Heim, D.; Minder, B.; et al. What Influences the Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviours of University Students? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, K.; Dedehayir, O.; Riverola, C.; Harrington, S.; Alpert, E. Exploring Consumer Perceptions of the Value Proposition Embedded in Vegan Food Products Using Text Analytics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Muñoz-Cantero, J.-M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Glinska-Newes, A. Modeling the Public Attitude towards Organic Foods: A Big Data and Text Mining Approach. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sintas, J.; Lamberti, G.; Lopez-Belbeze, P. Heterogenous Social Mechanisms Drive the Intention to Purchase Organic Food. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, R.; Music, J.; Charlebois, S.; Smyth, S. Canadian Consumers’ Perceptions of Sustainability of Food Innovations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Lendvai, M.B.; Beke, J. The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgaar, N.; Basha, N.K.; Hashim, H. Mapping the Landscape of Natural Food Consumption Barriers: A Bibliometric Analysis of Academic Publications. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 2024, 7, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, C.; Bai, J.; Fu, J. Chinese Consumer Quality Perception and Preference of Sustainable Milk. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, D.F.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. How to Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Food Choices: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Olafsdottir, G.; Bogason, S.; Hubbard, C.; Samoggia, A.; Nguyen, V.; Nguyen, D. Investigating and Stimulating Sustainable Dairy Consumption Behavior: An Exploratory Study in Vietnam. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, K.B.; Giroux, S.; Blekking, J.P.; Nix, E.; Fobi, D.; Farmer, J.; Todd, P.M. Eating Sustainably: Conviction or Convenience? Appetite 2023, 180, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Murcia, L.; Ramos-Mejía, M. Sustainable Diets and Meat Consumption Reduction in Emerging Economies: Evidence from Colombia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reipurth, M.F.S.; Hørby, L.; Gregersen, C.G.; Bonke, A.; Perez Cueto, F.J.A. Barriers and Facilitators towards Adopting a More Plant-Based Diet in a Sample of Danish Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamoah, F.A.; Acquaye, A. Unravelling the Attitude-Behaviour Gap Paradox for Sustainable Food Consumption: Insight from the UK Apple Market. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Tangeland, T. The Role of Consumers in Transitions towards Sustainable Food Consumption. the Case of Organic Food in Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, M.; Scalvedi, M.L.; Saba, A. Investigating Psychosocial Determinants in Influencing Sustainable Food Consumption in Italy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkaya, F.T.; Durak, M.G.; Doğan, O.; Bulut, Z.A.; Haas, R. Sustainable Consumption of Food: Framing the Concept through Turkish Expert Opinions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bååth, J. How Alternative Foods Become Affordable: The Co-Construction of Economic Value on a Direct-to-Customer Market. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.; Svenfelt, Å. Taking Sustainable Eating Practices from Niche to Mainstream: The Perspectives of Swedish Food-Provisioning Actors on Barriers and Potentials. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoni, E.; Ha, T.M.; Götze, F.; Häberli, I.; Ngo, M.H.; Huwiler, R.M.; Delley, M.; Nguyen, A.D.; Bui, T.L.; Le, N.T.; et al. Healthy or Environmentally Friendly? Meat Consumption Practices of Green Consumers in Vietnam and Switzerland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wood, L.C.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Zhang, A.; Farooque, M. Barriers to Sustainable Food Consumption and Production in China: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Analysis from a Circular Economy Perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, S.; Guru, S.; Shah, B. Analyzing Barriers for Organic Food Consumption in India: A DEMATEL-Based Approach. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 4459–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, V.; Essl, F.; Zulka, K.P.; Schindler, S. Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R.; Elshiewy, O. A Cross-Country Analysis of How Food-Related Lifestyles Impact Consumers’ Attitudes towards Microalgae Consumption. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnoefer, L.M.; Riefler, P.; Meixner, O. What Drives the Choice of Local Seasonal Food? Analysis of the Importance of Different Key Motives. Foods 2021, 10, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Oates, C.J.; Jones, C.R.; Alevizou, P. Reducing Meat Consumption at Work and at Home: Facilitators and Barriers That Influence Contextual Spillover. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 671–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing Organic Food Consumption: An Integrating Model of Drivers and Barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Lund, T.B. Reducing Meat Consumption in Meat-Loving Denmark: Exploring Willingness, Behavior, Barriers and Drivers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable Consumption and the Attitude-Behaviour-Gap Phenomenon—Causes and Measurements towards a Sustainable Development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A.; De Keyzer, F.; van Prooijen, A.-M.; Peiffer, L.C.; Wang, Y. Addressing Grand Challenges in Sustainable Food Transitions: Opportunities Through the Triple Change Strategy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Ding, L. A Q-Rung Orthopair Fuzzy Generalized TODIM Method for Prioritizing Barriers to Sustainable Food Consumption and Production. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 45, 5063–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, H.; Gould, J.; Danner, L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Yang, Q. “I Guess It’s Quite Trendy”: A Qualitative Insight into Young Meat-Eaters’ Sustainable Food Consumption Habits and Perceptions towards Current and Future Protein Alternatives. Appetite 2023, 190, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, P.K.; Srivastava, A.; Ahmad, A. Motivators and Barriers to Sustainable Food Consumption: Qualitative Inquiry about Organic Food Consumers in a Developing Nation. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24, e1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Greenland, S. Sustainable Food Consumption: Investigating Organic Meat Purchase Intention by Vietnamese Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocean, C.G. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Digital Technologies on Sustainable Food Production and Consumption in the European Union. Foods 2024, 13, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Galati, A. Systematic Literature Review on the Nexus of Food Waste, Food Loss and Cultural Background. Int. Mark. Rev. 2024, 41, 683–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Pala, U.; Özcan, N. Mobile Applications as a next generation solution to prevent food waste. EGE Acad. Rev. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewski, K.; Sobocinska, M.; Krupowicz, J.; Graczyk, A.; Mazurek-Lopacinska, K. Changes in the polish market for agricultural organic products. Ekon. Srodowisko-Econ. Environ. 2023, 84, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrariu, R.; Sacala, M.; Pistalu, M.; Dinu, M.; Deaconu, M.; Constantin, M. A comprehensive food consumption and waste analysis based on ecommerce behaviour in the case of the AFER community. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2022, 21, 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gassler, B.; Xiao, Q.; Kühl, S.; Spiller, A. Keep on Grazing: Factors Driving the Pasture-Raised Milk Market in Germany. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcao, D.; Roseira, C. Mapping the Socially Responsible Consumption Gap Research: Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1718–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer Behaviour and Household Food Waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychological Barriers to Climate-Friendly Food Choices. Available online: https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1015-60462023000100006 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Gavahian, M.; Sheu, S.-C.; Magnani, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Emerging Technologies for Mycotoxins Removal from Foods: Recent Advances, Roles in Sustainable Food Consumption, and Strategies for Industrial Applications. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, 1718–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujayasree, O.J.; Chaitanya, A.K.; Bhoite, R.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; Gavahian, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Ozone: An Advanced Oxidation Technology to Enhance Sustainable Food Consumption through Mycotoxin Degradation. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targino de Souza Pedrosa, G.; Pimentel, T.C.; Gavahian, M.; Lucena de Medeiros, L.; Pagán, R.; Magnani, M. The Combined Effect of Essential Oils and Emerging Technologies on Food Safety and Quality. LWT 2021, 147, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenstrøm, N.; Hebrok, M. Towards Realizing the Sustainability Potential within Digital Food Provisioning Platforms: The Case of Meal Box Schemes and Online Grocery Shopping in Norway. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukraisa, S.; Phlainoi, S.; Phlainoi, N.; Kantamaturapoj, K. Toward a New Paradigm on Food Literacy and Learning Development in the Thai Context. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.W.; Alanezi, F. Sustainable Eating Futures: A Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Future Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Qiao, G. Quantification, Environmental Impact, and Behavior Management: A Bibliometric Analysis and Review of Global Food Waste Research Based on CiteSpace. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantamaturapoj, K.; McGreevy, S.; Thongplew, N.; Akitsu, M.; Vervoort, J.; Mangnus, A.; Ota, K.; Rupprecht, C.; Tamura, N.; Spiegelberg, M.; et al. Constructing Practice-Oriented Futures for Sustainable Urban Food Policy in Bangkok. Futures 2022, 139, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Harms, T.; Fiebelkorn, F. Acceptance of Cultured Meat in Germany-Application of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2022, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzler, S.; Kempen, R.; Mueller, K. Predicting Sustainable Consumption Behavior: Knowledge-Based, Value-Based, Emotional and Rational Influences on Mobile Phone, Food and Fashion Consumption. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, H.; He, W.; Mou, J.; Siponen, M. Consumption Behavior of Eco-Friendly Products and Applications of ICT Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z. A Review of Social Roles in Green Consumer Behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2033–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Hu, G.; Shi, Y. Processes, Benefits, and Challenges for Adoption of Blockchain Technologies in Food Supply Chains: A Thematic Analysis. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2021, 19, 909–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vern, P.; Panghal, A.; Mor, R.S.; Kamble, S.S. Blockchain Technology in the Agri-Food Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review of Opportunities and Challenges. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining Consumer Purchase Behavior for Organic Milk: Including Trust and Green Self-Identity within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Martínez-Fiestas, M.; Aranda, L.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. Is It an Error to Communicate CSR Strategies? Neural Differences among Consumers When Processing CSR Messages. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior: Scale Review, Development, and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2697–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjärnemo, H.; Södahl, L. Swedish Food Retailers Promoting Climate Smarter Food Choices-Trapped between Visions and Reality? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J. Structural Topic Modeling for Corporate Social Responsibility of Food Supply Chain Management: Evidence from FDA Recalls on Plant-Based Food Products. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Maleki, F. From Decision to Run: The Moderating Role of Green Skepticism. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farm to Fork Strategy—European Commission. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 9 February 2025).

| Theme | Frequency | Example Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Health Concerns | 20 | [38,39,40,41] |

| Environmental Awareness | 19 | [38,39,42,43] |

| Ethical and Moral Beliefs | 15 | [38,44,45,46] |

| Social and Personal Norms | 12 | [38,43,44,48] |

| Taste and Quality | 14 | [38,39,42,49] |

| Support for Local Economies | 10 | [42,49,50] |

| Knowledge and Awareness | 8 | [38,46] |

| Religious and Cultural Factors | 5 | [38,41] |

| Emotional and Psychological Fulfillment | 6 | [40,50] |

| Economic and Practical Considerations | 7 | [43,46] |

| Categories of Barriers | Specific Barriers | Co-Occurrence of Categories | Example of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | High prices, reduced willingness to pay, financial constraints | Economic, availability, knowledge | [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Availability | Lack of availability, limited variety, unavailability | Availability, economic, knowledge | [55,58,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Knowledge | Lack of awareness, insufficient information, misunderstanding | Knowledge, economic, availability | [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Social and Cultural | Family influence, cultural traditions, social norms | Social and cultural, economic, knowledge | [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Psychological | Resistance to change, skepticism, emotional attachment | Psychological, economic, knowledge | [8,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Policy and Regulation | Lack of support, policy fragmentation, bureaucratic difficulties | Policy and regulation, economic, knowledge | [59,60,63,65,66,67,74,75,82,85] |

| Specific Barrier | Frequency | Example Articles |

|---|---|---|

| High price | 18 | [51,52,53,54] |

| Lack of availability | 14 | [51,58,63] |

| Lack of knowledge/awareness | 16 | [52,61,65] |

| Consumer resistance/skepticism | 10 | [51,76,78] |

| Habitual behavior | 8 | [53,70,72] |

| Cultural and social norms | 12 | [56,63,64] |

| Distrust in Labels/Certifications | 7 | [59,76,78] |

| Perceived quality/taste | 6 | [59,67,68] |

| Lack of information | 9 | [53,65,71] |

| Psychological barriers | 5 | [51,70,76] |

| Economic and marketing factors | 6 | [54,62,63] |

| Functional barriers | 4 | [51,57,73] |

| Family influence | 5 | [53,64,70] |

| Environmental and physical context | 4 | [54,63,65] |

| Lack of unified policy/regulation | 4 | [60,63,65] |

| Food safety concerns | 3 | [64,65,76] |

| Lack of motivation | 3 | [67,70,73] |

| Miscommunication | 2 | [54,63] |

| Lack of transparent information | 3 | [63,65,74] |

| Greenwashing | 2 | [74,76] |

| Lack of collaboration | 2 | [63,65] |

| Lack of environmental education | 2 | [65,80] |

| Lack of economies of scale | 1 | [65] |

| Lack of standards and benchmarking | 1 | [65] |

| Distrust in labels | 1 | [67] |

| Lack of state support | 1 | [82] |

| Low yields and high production costs | 1 | [82] |

| Bureaucratic and administrative difficulties | 1 | [82] |

| Digital exclusion | 1 | [79] |

| Technical complexity | 1 | [79] |

| Data security concerns | 1 | [79] |

| Training and adoption challenges | 1 | [79] |

| Resistance to change | 1 | [79] |

| Economic disparities | 1 | [79] |

| Lack of time | 1 | [71] |

| Perceived environmental impact | 1 | [71] |

| Lack of sense of responsibility | 1 | [85] |

| Contextual and social factors | 1 | [85] |

| Sourcing aspects | 1 | [85] |

| Shopping behaviors and meal planning trends | 1 | [86] |

| Insufficient information campaigns | 1 | [86] |

| Year | High Price | Lack of Availability | Lack of Knowledge/Awareness | Consumer Resistance/Skepticism | Habitual Behavior | Cultural and Social Norms | Distrust in Labels/Certifications | Perceived Quality/Taste | Lack of Information | Psychological Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2020 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2021 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2022 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2023 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2024 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Categories of Technologies | Specific Technology | Example of Article |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Proteins | Plant-based alternative protein (PBM/S), lab-grown meat/seafood (CBM/S) | [76] |

| Dairy Alternatives | Precision fermented dairy products (PFDs) | [76] |

| Decontamination | Cold plasma and ultrasound, mycotoxin decontamination, ozone | [88,89] |

| Preservation | Essential oils (EOs), emerging technologies (ETs) | [90] |

| Digital Platforms | Meal box schemes and online food shopping | [91] |

| Food Literacy | Food production technologies, storage, transport and processing technologies, Transparency and traceability in the supply chain | [92] |

| Smart Technologies | AI and GPS, 3D printing | [93] |

| Digital Transformation | Smart refrigerators and apps | [93] |

| Digital Technologies | AI, big data, IoT, cloud computing, monitoring and managing supply chains | [79] |

| Waste Management | Mobile applications, digital platforms, IoT systems, lean management techniques, food surplus management, demand analysis and waste forecasting | [94] |

| Smart Systems | AI, smart shopping assistants | [95] |

| Educational Tools | VR and mobile technologies | [95] |

| Smart Gardening | Smart gardening systems and chemical test kits | [95] |

| Traceability | Blockchain | [96] |

| ICT | Information and communication technologies (ICT), ICT innovations, ICT platforms | [97,98] |

| Digital Platforms | Online platforms and social media | [99] |

| Traceability | IoT and blockchain | [98] |

| Mobile Apps | Mobile apps | [98] |

| Categories of Technologies | Frequency of Appearance | Specific Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Proteins | 2 | Plant-based alternative protein (PBM/S), lab-grown meat/seafood (CBM/S) |

| Dairy Alternatives | 1 | Precision fermented dairy products (PFDs) |

| Decontamination | 3 | Cold plasma and ultrasound, mycotoxin decontamination, ozone |

| Preservation | 2 | Essential oils (EOs), emerging technologies (ETs) |

| Digital Platforms | 2 | Meal box schemes and online food shopping, online platforms and social media |

| Food Literacy | 3 | Food production technologies, storage, transport and processing technologies, transparency and traceability in the supply chain |

| Smart Technologies | 2 | AI and GPS, 3D printing |

| Digital Transformation | 1 | Smart refrigerators and apps |

| Digital Technologies | 2 | AI, big data, IoT, cloud computing, monitoring and managing supply chains |

| Waste Management | 4 | Mobile applications, digital platforms, IoT systems, lean management techniques, food surplus management, demand analysis and waste forecasting |

| Smart Systems | 2 | AI, smart shopping assistants |

| Educational Tools | 1 | VR and mobile technologies |

| Smart Gardening | 1 | Smart gardening systems and chemical test kits |

| Traceability | 2 | Blockchain, IoT, and blockchain |

| ICT | 3 | Information and communication technologies (ICT), ICT innovations, ICT platforms |

| Category of Corporate Initiatives | Frequency | Specific Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Education and Awareness | 1 | Educating consumers about sustainable products |

| Product Availability and Diversity | 1 | Improving availability and variety of sustainable products |

| Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | 3 | Adopting CSR measures, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| Promotion and Marketing | 1 | Offering discounts, awareness campaigns for organic products |

| Labeling and Certification | 2 | Supporting certification programs |

| Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | 1 | Promoting fair trade, ensuring fair wages and decent working conditions |

| Environmental Policies and Practices | 1 | Addressing climate change, promoting organic/local/seasonal foods, minimizing food waste |

| Stakeholder Engagement and Policy Development | 1 | Engaging stakeholders, developing food safety strategies |

| Category | CSR | Promotion and Marketing | Labeling and Certification | Consumer Education | Product Availability and Diversity | Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | Green Product Lines | Environmental Policies | Stakeholder Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Promotion and Marketing | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Labeling and Certification | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consumer Education | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Product Availability and Diversity | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Green Product Lines | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental Policies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Stakeholder Engagement | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Year | Category of Corporate Initiatives | Specific Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Adopting CSR measures, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| 2015 | Promotion and Marketing | Offering discounts, awareness campaigns for organic products |

| 2015 | Labeling and Certification | Supporting certification programs |

| 2015 | Environmental Policies and Practices | Addressing climate change, promoting organic/local/seasonal foods, minimizing food waste |

| 2016 | Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | Promoting fair trade, ensuring fair wages and decent working conditions |

| 2018 | Consumer Education and Awareness | Educating consumers about sustainable products |

| 2018 | Product Availability and Diversity | Improving availability and variety of sustainable products |

| 2018 | Improving Corporate Skills | Building green procurement intentions and information seeking |

| 2019 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Engaging in CSR activities, reducing carbon footprint, using sustainable materials |

| 2019 | Green Product Lines | Development and promotion of organic products |

| 2019 | Sustainability Certifications | Obtaining certifications to assure sustainability |

| 2021 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Adopting ethical and sustainable practices, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| 2024 | Stakeholder Engagement and Policy Development | Engaging stakeholders, developing food safety strategies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nichifor, B.; Zait, L.; Timiras, L. Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052233

Nichifor B, Zait L, Timiras L. Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052233

Chicago/Turabian StyleNichifor, Bogdan, Luminita Zait, and Laura Timiras. 2025. "Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052233

APA StyleNichifor, B., Zait, L., & Timiras, L. (2025). Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(5), 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052233