1. Introduction

Sustainability is a critical consideration in shaping the future economy and fostering resilient, thriving communities. It focuses on meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own [

1,

2]. Entrepreneurship, as a driver of job creation, enhanced competitiveness, and economic modernization, plays a pivotal role in advancing sustainable development through innovation [

3,

4]. Increasingly recognized as a key catalyst for sustainable economic growth, entrepreneurship holds particular significance for emerging economies [

5,

6]. It serves as a mechanism for aligning economic development with sustainability objectives [

7]. Furthermore, entrepreneurship is regarded as an engine for economic development that is especially valuable for rapidly growing emerging economies, as studies highlight a reciprocal relationship between sustainable development and entrepreneurship [

8,

9,

10].

Combining female entrepreneurship with sustainability offers a compelling avenue for advancing economic growth and sustainable development [

11,

12,

13], especially in developing countries [

14,

15]. The United Nations has identified women’s entrepreneurship as a key driver for achieving economic growth and meeting current and future sustainable goals and targets [

16]. Fernández et al. [

11] highlight the novelty of this intersection, calling for further research to address existing knowledge gaps and deepen understanding of its potential impact.

Growing interest has been fostered around the integration of sustainability into entrepreneurial ventures when it comes to the role of female entrepreneurs. The impact of female entrepreneurship on sustainable economic growth can manifest through various factors, including enhanced job creation [

17], innovation [

18], economic diversification [

19], inclusive growth [

20], community development [

21], and an increase in Gross National Product (GNP) [

22].

This positive relationship between sustainable economic development and female entrepreneurship can be attributed to two main facets. The first one is that female entrepreneurs have been observed to more frequently and effectively integrate sustainability into their business models than their male counterparts [

23,

24]. The second facet is through the emancipation of a key component of society or the national labor force after spurring greater economic output [

13]. Entrepreneurial output can be more effectively and sustainably directed through appropriate regulatory and policy frameworks. This approach is illuminated by the institutional theory, which emphasizes how formal and informal institutions, such as rules, norms, and policies [

25,

26], shape entrepreneurial behavior [

27]. In the context of female entrepreneurship, these institutional frameworks—comprising governmental policies, financial support systems, and societal norms—serve as critical enablers or barriers to women’s participation and success in entrepreneurial activities. The institutional support helps women launch businesses that are often more sustainable and inclusive, aligning with national goals for long-term economic growth. In supportive entrepreneurial ecosystems, sustainability-focused policies reinforce female entrepreneurs’ tendency to adopt environmentally and socially responsible business practices, thereby contributing to sustainable economic development [

28].

Women entrepreneurs are recognized as key drivers of growth and development in emerging countries, playing a crucial role in fostering innovation, expansion, and economic development [

29]. Research highlights the untapped potential of women in the business environment, underscoring the significant impact of women entrepreneurship on welfare and sustainability [

30,

31]. Despite various initiatives aimed at promoting women’s entrepreneurship in developing countries, women still own and lead fewer businesses, earn less, experience slower growth, face higher failure rates, and tend to be more need-driven in their entrepreneurial pursuits [

29].

While much research has explored the economic benefits of entrepreneurship globally, there remains limited focus on its role in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region [

32]. Exploring the intersection of women, entrepreneurship, and sustainability within the Arab Gulf region—comprising the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar—offers a rich area for research, particularly as sustainability, namely female entrepreneurship and gender equality, has become increasingly central to GCC development plans [

7]. Accordingly, GCC countries are actively mobilizing their resources and efforts to promote entrepreneurship and align economic development with sustainability objectives [

33,

34].

However, female entrepreneurs in the GCC face unique challenges that require further exploration [

17]. Recent literature on female entrepreneurship highlights the importance of exploring and identifying key factors that enable and constrain female entrepreneurship in the Middle East [

30,

31,

35,

36]. This study seeks to investigate the constraints and opportunities for fostering entrepreneurship, particularly in resource-rich economies where necessity-based drivers are often absent. Unlike economies with lower levels of public welfare, the high social welfare provisions in the GCC can act as a barrier to entrepreneurship, potentially undermining economic diversification and sustainable development [

5].

To address these challenges, GCC countries must implement measures to develop a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem and promote entrepreneurship aligned with sustainable value creation [

37,

38]. This effort requires identifying the factors that influence entrepreneurship, particularly female entrepreneurship, through a holistic, multi-level perspective and institutional lens [

39]. Despite growing recognition of entrepreneurship’s significance, there remains a lack of research examining the relationship between female entrepreneurship and sustainable development in the GCC, with only a handful of studies addressing this relationship. While these studies highlight the importance of micro-level motivations, meso-level support systems, and macro-level socio-cultural and policy contexts, the analysis remains fragmented. There is insufficient understanding of the interplay between these levels and how they collectively shape female entrepreneurs’ contributions to sustainability. Furthermore, the geographic scope is narrow, primarily concentrating on Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Furthermore, limited studies have adopted a multi-level approach using an institutional perspective to investigate the factors affecting female entrepreneurship, emphasizing the need for further exploration. As Hashim [

40] highlights, it is essential to address the specific challenges and opportunities faced by women entrepreneurs in the region, with tailored strategies to support their endeavors effectively. Al Boinin [

41] further underscores the importance of promoting context-dependent knowledge to guide policymakers in formulating more inclusive and effective policies. It is therefore crucial for research to adopt a more comprehensive, holistic, and multi-level approach while expanding its scope to encompass all GCC countries. This would help identify the factors that enable or obstruct women’s ability to contribute to sustainability through entrepreneurship, paving the way for targeted strategies to empower female entrepreneurs. A thorough understanding of these factors is essential to fully leverage their potential in sustainable economic development.

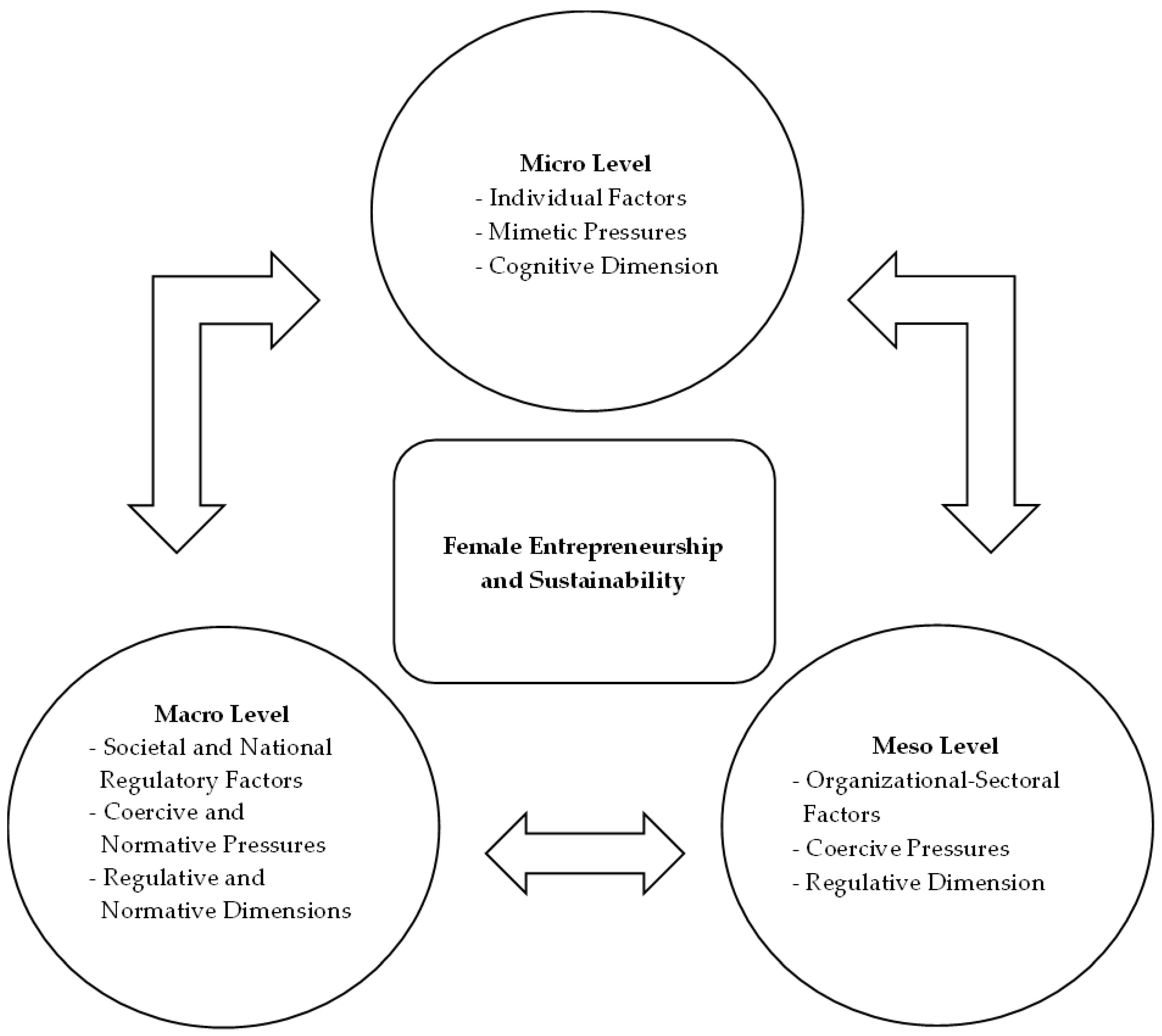

This study aims to address multiple calls in the field by conducting a systematic literature review to examine the factors influencing female entrepreneurship in the GCC. Using a multilevel framework encompassing micro (individual), meso (organizational/sectoral), and macro (societal/national) levels, this study integrates corresponding institutional dimensions and mechanisms (cognitive/mimetic, coercive/regulative and normative). The article begins by presenting the conceptual framework adopted for analyzing secondary data from the systematic literature review, followed by a detailed explanation of the methodology. Next, it provides contextualized data from international organizations such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), alongside the results of the systematic literature review. The discussion highlights key findings, culminating in policy recommendations and practical implications for promoting female entrepreneurship and sustainability in the GCC.

2. Conceptual Framework: A Multi-Level and Institutional Perspective

This study adopts an institutional perspective as the foundational theoretical framework, with a particular focus on neo-institutional theory for the analysis. The institutional theory provides valuable insights into how institutions—encompassing formal and informal rules, norms, and practices [

25]—shape entrepreneurship [

27]. Institutions impose restrictions by defining legal, moral, and cultural boundaries, distinguishing acceptable from unacceptable behavior. However, it is equally important to recognize that institutions not only constrain but also enable and support entrepreneurial activities by providing guidance and legitimacy. To capture the multifaceted nature of entrepreneurship, an integrated framework and holistic perspective are necessary. Also, given the contextual nature of entrepreneurship, adopting a socially embedded logic is essential.

The neo-institutional theory builds on the foundational ideas of the institutional theory but places greater emphasis on the dynamic interplay between human action, organization behavior, and their institutional environment. Key contributions to this theory come from DiMaggio and Powell [

42] and Scott [

43], who elaborated on how institutional forces drive homogeneity and shape practices and decisions. According to the neo-institutional theory, institutional pillars serve as frameworks of meaning that guide organization behaviors and human actions. DiMaggio and Powell [

42] identify three pressure mechanisms of institutional isomorphism: mimetic, coercive, and normative. Scott [

43] further refines these mechanisms under three institutional dimensions: cognitive, regulative, and normative. These dimensions represent a continuum, ranging from conscious to unconscious processes and from legally enforced to taken-for-granted norms.

These institutional facets offer a comprehensive lens for analyzing entrepreneurship, revealing both the fostering and inhibiting factors. Entrepreneurs, at the individual level, must seek legitimacy within a shared frame of reference (cognitive dimension and mimetic mechanisms). Simultaneously, they must adhere to legal requirements and formal processes at the organizational-sectoral level, governed by the regulatory pressures of those providing critical resources and opportunities (regulative dimension and coercive mechanisms). At the macro level, entrepreneurs’ attitudes and activities are shaped by prevailing societal norms and values (normative dimension and mechanisms). They are also influenced by national-level regulatory structures that either constrain their behavior or empower their actions (regulative dimension and coercive mechanisms).

These three dimensions—cognitive, regulative, and normative—significantly affect entrepreneurial activities and, consequently, the likelihood of fostering entrepreneurship, economic growth, and sustainability. However, as DiMaggio and Powell [

42] caution, “this typology is an analytical one”. The three mechanisms are not always empirically distinguishable and may overlap, making them challenging to disentangle.

Additionally, there is also a potential overlap with the three levels of analysis. While the macro level is often associated with norms, values, and cultural expectations, it also encompasses formal, national-level structures, such as laws, constitutions, and overarching regulatory systems and government programs. These are regulative in nature but operate at a broader level, influencing all sectors and organizations within a country or region. In contrast, the meso level pertains to localized legal procedures, such as industry standards, organizational practices, and networking and capacity-building opportunities. This distinction between macro and meso levels is critical for clarity, as both levels involve regulative elements but differ in scope and applicability.

This institutional framework complements the multi-level analysis by focusing on the formal and informal institutions that shape or constrain opportunities for female entrepreneurship [

44] at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels [

39]. Given that institutions significantly impact entrepreneurial activities, the institutional lens explains how cross-national differences in entrepreneurship are influenced by a broader set of guiding institutions [

45]. The proposed framework clearly illustrates how the institutional theory—specifically, the neo-institutional theory—combined with a multi-level research design, enhances our understanding of the multidimensional factors influencing entrepreneurship in context. Although the three levels are presented separately for analysis, it is important to acknowledge the interconnected impact of these factors on female entrepreneurship, with the crucial role of context and national institutions shaping these complex dynamics through the institutional lens [

39].

Indeed, researchers often emphasize one institutional pillar over the others. Notably, Mizruchi and Fein [

46] reviewed 160 studies on institutional theory and found that only two studies operationalized all three forms of institutional isomorphism as identified by DiMaggio and Powell [

42]. They argue that focusing solely on single isomorphic may obscure other operative processes, potentially leading to a partial or distorted interpretation of the phenomenon [

46].

In light on these observations, we propose an inclusive and integrative framework that incorporates multiple levels of analysis, alongside the corresponding institutional pressures and dimensions (

Figure 1). This framework serves as a heuristic tool to better understand and analyze the diverse factors influencing entrepreneurship and its interaction with institutional structures at different levels. It aims to provide policymakers with a comprehensive and holistic perspective for designing effective policies that address the multifaceted and multidimensional nature of female entrepreneurship in relation with sustainable economic development in the GCC context.

3. Female Entrepreneurship and Sustainability in the GCC: A Contextual Approach

Research shows that women entrepreneurs tend to have lower self-efficacy and are more risk-averse compared to men, who display greater confidence and willingness to take risks [

47,

48]. Women are also more likely to be motivated by social goals and balancing family responsibilities, while men are generally driven by economic gain [

49]. Additionally, women face social stereotypical challenges and greater barriers to accessing financial resources and support networks, which are often male dominated [

13,

50]. As highlighted by Hashim [

40], women entrepreneurs in the Gulf States are often misunderstood due to the application of Western epistemology without considering the unique contextual dimensions that influence their activities. Research indicates that women face challenges related to institutional factors, such as high unemployment rates among highly qualified women [

7], and societal factors, including patriarchal and tribal cultures [

51,

52]. While some argue that Islam supports women’s economic participation [

35], others highlight the patriarchal misinterpretation of religion hindering women’s entrepreneurship [

36,

39,

53]. Understanding these contextual challenges is crucial for developing a context-specific epistemology of entrepreneurship in the GCC and advancing the conception of gender and entrepreneurship in the region for a sustainable development.

According to Frankze et al. [

54], the national institutional context shapes female entrepreneurship. Chikh-Amnache and Mekhzoumi [

55] further highlight the role of socioeconomic factors in influencing female entrepreneurship in Southeast Asia. Similarly, Chiplunkar and Goldberg [

56] emphasize that barriers to female entrepreneurship in South Asia extend beyond legal constraints to include societal norms and attitudes, underscoring the need for a comprehensive policy approach. Research also indicates that female entrepreneurs in developing and emerging countries face significant obstacles, including psychological perceptions, gender inequalities [

57], limited access to resources, insufficient human capital [

58], and challenges in achieving work-life balance [

57,

58]. However, while studies in Asian countries suggest that female entrepreneurship is often driven by opportunity rather than necessity [

59], Deng et al. [

60] argue that necessity-based female entrepreneurship tends to thrive in developing countries, whereas opportunity-based entrepreneurship is more prevalent in developed economies. Nonetheless, some developing countries, such as Malaysia, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam, exhibit higher rates of opportunity-driven female entrepreneurship than necessity-driven ones. Similar research likewise denotes that female entrepreneurship in emerging and developing countries, including Asia, Latin America, and Africa [

61], is not always opportunity driven but necessity driven [

61,

62]. Frankze et al. [

54] further note that substantial progress has been made in supporting female entrepreneurs in countries like China, Malaysia, and Thailand, where government-backed initiatives have played a crucial role. In contrast, in countries such as India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, female-led businesses are often necessity-driven. Despite these advances, persistent socio-cultural challenges and significant educational gaps continue to hinder women’s economic participation across all Asian countries.

These studies collectively underscore that institutional mechanisms influencing female entrepreneurship in developed countries do not apply uniformly to developing countries. Moreover, even among developing and emerging economies, different structural and socio-cultural factors shape female entrepreneurship in distinct ways. GCC countries differ significantly from other emerging regions, and even other MENA countries, due to unique socio-economic and cultural factors.

GCC countries face distinct challenges shaped by their economic structures, conservative social frameworks, and cultural norms surrounding women’s roles in society [

63]. While there have been notable strides, such as an increase in female workforce participation, the entrepreneurial ecosystem remains constrained by limited access to capital and institutional barriers, despite the region’s wealth. Furthermore, compared to other MENA countries like Lebanon [

31] or Morocco [

53], which have seen more grassroots-driven initiatives for female entrepreneurship, the GCC’s top-down, state-driven reforms have created a unique set of opportunities and challenges, particularly in aligning cultural values with modern entrepreneurial practices. These differences underscore the importance of understanding the GCC’s specific context when discussing female entrepreneurship and sustainable economic development.

Sustainability has become a policy imperative across all GCC countries, with female entrepreneurship emerging as a key strategy to promote economic diversification and sustainable development. As GCC nations shift from resource-dependent (oil-based) economies to knowledge-driven ones, entrepreneurship is increasingly prioritized to address unemployment, foster innovation, and empower women [

19,

41,

64]. Economic diversification, a longstanding theme in the GCC’s development strategies, has gained renewed urgency following the 2014 oil price decline and the establishment of ambitious national visions [

19,

65]. This emphasis aligns with strategic initiatives like Saudi and Qatar’s Vision 2030, which highlight the importance of women’s participation in economic and leadership roles [

66]. This focus underscores the importance of empowering women to contribute to diverse economic sectors and societal progress. Female entrepreneurs play a pivotal role in reducing the GCC’s reliance on oil by fostering businesses in sectors such as technology, healthcare, education, and tourism [

19,

41].

To achieve this transition, GCC countries are leveraging their financial resources to support start-ups and encourage entrepreneurship to reduce reliance on oil revenues [

37]. In these countries, entrepreneurship has been ascribed an active role in equilibrating economic development with sustainability goals [

7]. With promoting entrepreneurship and advancing gender equality now central to national development strategies [

33,

34], entrepreneurs—especially female entrepreneurs—are recognized as vital to economic diversification and broader economic growth [

19].

Women-led startups and small-medium enterprises (SMEs) drive innovation and diversify economic activities, introducing unique products and services while contributing to the growth of emerging sectors like e-commerce and fintech [

67,

68], which are vital for achieving balanced economic development [

69]. Encouraging women to start businesses also promotes gender equity and social inclusion, which are essential for sustainable development [

23]. Women-led enterprises create jobs, address unemployment, and improve living standards, thereby reducing poverty [

11,

70]. Moreover, female entrepreneurs often emphasize education and skill development for themselves and their employees, contributing to long-term economic resilience and sustainability [

7].

Governments in the GCC have implemented numerous initiatives to empower female entrepreneurs, including financial incentives like grants and loans, training programs, and regulatory reforms aimed at easing business operations. Organizations such as Saudi Arabia’s Monshaat [

71,

72] and the UAE’s Khalifa Fund for Enterprise Development provide vital resources [

73], while programs like Bahrain’s Tamkeen [

74,

75] equip women with the skills needed to succeed in entrepreneurship. Such initiatives have significantly increased the number of women-led businesses, fostering growth across diverse sectors.

The growth of female entrepreneurship is also driving cultural change by challenging traditional perceptions of women’s roles in the economy [

76,

77]. Successful women entrepreneurs inspire others to pursue business opportunities and often focus on community development, further enhancing social well-being. This cultural shift positions women as agents of economic and societal transformation in the GCC. Female entrepreneurship has become a cornerstone of economic and social progress in GCC countries [

78]. Hence, understanding the factors affecting this phenomenon is critical for the sustainability of these countries.

4. Methodology: A Systematic Literature Review

This study employs a systematic literature review (SLR) to analyze how female entrepreneurship in the GCC region is conceptualized across academic literature. The main objectives are to map studies across micro-, meso-, and macro-dimensions, identify key motivations and challenges at each level, and highlight gaps in the literature to inform evidence-based policy recommendations.

The study follows established SLR protocols ([

79] and was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [

80] to ensure rigor, transparency, and replicability. The SLR is a rigorous and reliable method for analyzing publications within a specific period of time, identifying research trends, and conducting reliable reviews in the field of entrepreneurship [

11]. The criteria followed in this SLR are as follows:

The databases utilized for identifying the relevant literature were Web of Science and Scopus.

The selected articles were limited to those published in English under a peer-reviewed process.

All publications, including book chapters, book reviews, books, conference proceedings, reports, and working papers, were excluded from this analysis. The review focused solely on peer-reviewed journal articles.

The review spans publications from 2003 to 2024, reflecting the organic growth of research on this topic.

Keywords related to female entrepreneurship and the GCC region were searched using Scopus and Web of Science (Query for Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“female entrepreneurship” OR “women entrepreneurship” OR “women entrepreneurs” OR “female entrepreneurs”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Gulf Cooperation Council” OR “GCC” OR “Bahrain” OR “Kuwait” OR “Oman” OR “Qatar” OR “Saudi Arabia” OR “United Arab Emirates” OR “UAE”); Query for Web of Science: TS = (“female entrepreneurship” OR “women entrepreneurship” OR “women entrepreneurs” OR “female entrepreneurs”) AND TS = (“Gulf Cooperation Council” OR “GCC” OR “Bahrain” OR “Kuwait” OR “Oman” OR “Qatar” OR “Saudi Arabia” OR “United Arab Emirates” OR “UAE”)).

The abstract of each article was reviewed to confirm its relevance.

Articles deemed relevant in the previous step were subsequently downloaded and thoroughly examined.

Articles were not limited to those published in journals with a specific impact factor.

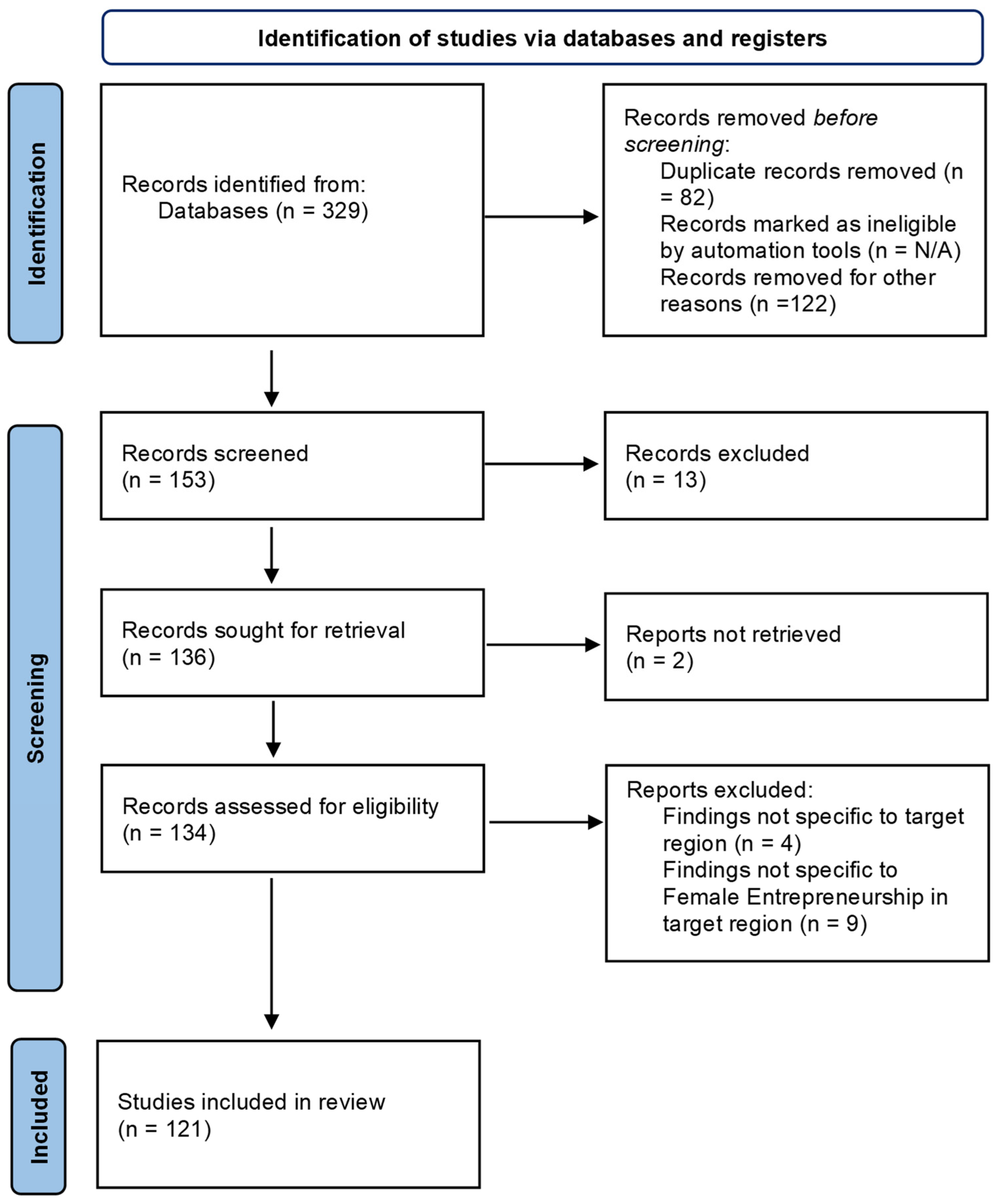

The initial search in Scopus and Web of Science, conducted in September 2024 and rechecked in December 2024, using specified keywords and Boolean operators, yielded 329 articles. After removing duplicates and non-peer-reviewed materials, such as book chapters, dissertations, and conference papers, 153 peer-reviewed journal articles remained. Titles and abstracts were then screened for relevance to female entrepreneurship in the GCC, resulting in a final dataset of 121 articles for full-text analysis.

A standardized data extraction form (spreadsheet) to extract study characteristics, primary level of analysis, and factors was developed. The search, filtering, and classification processes were independently reviewed by the two co-authors and a research assistant to ensure accuracy and minimize bias. Multiple iterative review rounds were conducted to refine the classification through discussion and consensus at each stage. All articles underwent a stringent multi-phase screening and selection process, as illustrated in the flow diagram (

Figure 2).

Articles were categorized based on its primary level of analysis into micro (individual skills, motivations, and traits), meso (organizational-sectoral factors), and macro (socio-cultural norms, and national regulatory contexts and policies) levels. Studies addressing multiple levels were classified based on their primary analytical focus. Coding was conducted iteratively, with inter-coder reliability checks ensuring consistency and reducing subjectivity bias. The extracted data were organized in a spreadsheet and categorized into motives and challenges, each further classified into micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors to ensure coding consistency. To address variations in terminology, synonymous or overlapping phrases (e.g., “maintaining family responsibilities” and “parental duties”) were consolidated under standardized codes, such as “Work-Life Balance”, unless they referred to distinct concepts. Once the coding process for all articles was completed, the frequency of each identified motive or challenge was quantified and visualized. For example, if “Work-Life Balance” was recorded as a micro-level challenge in 77 articles, this occurrence was documented as such.

After coding, the data were analyzed to identify patterns and linkages, with the findings consolidated into thematic groups of motives and challenges. These themes were systematically structured within a multi-level framework (micro, meso, macro) to enhance clarity and readability. For example, micro-level challenges such as “Lack of Confidence”, “Fear of Failure”, “Risk Aversion”, and “Psychological Stress” were grouped under the broader theme of “Personal and Psychological Constraints”.

The data were organized within a structured framework, quantifying key factors and identifying themes related to motivations and challenges at the micro-, meso-, and macro-level, with each level corresponding to its respective institutional dimension: cognitive, regulative, and normative/regulative and institutional pressures: mimetic, coercive, and normative. This approach ensured alignment between the adopted conceptual framework and the data analysis, thereby enhancing consistency and coherence throughout the study.

Supplementary data from organizations like the ILO and GEM were integrated to triangulate findings. This approach aligns scholarly insights with empirical indicators, providing a robust understanding of female entrepreneurship in the GCC. The study identifies critical themes, gaps, and trends, offering a foundation for tailored policy recommendations that support female entrepreneurial ecosystems in the region allowing for a sustainable development.

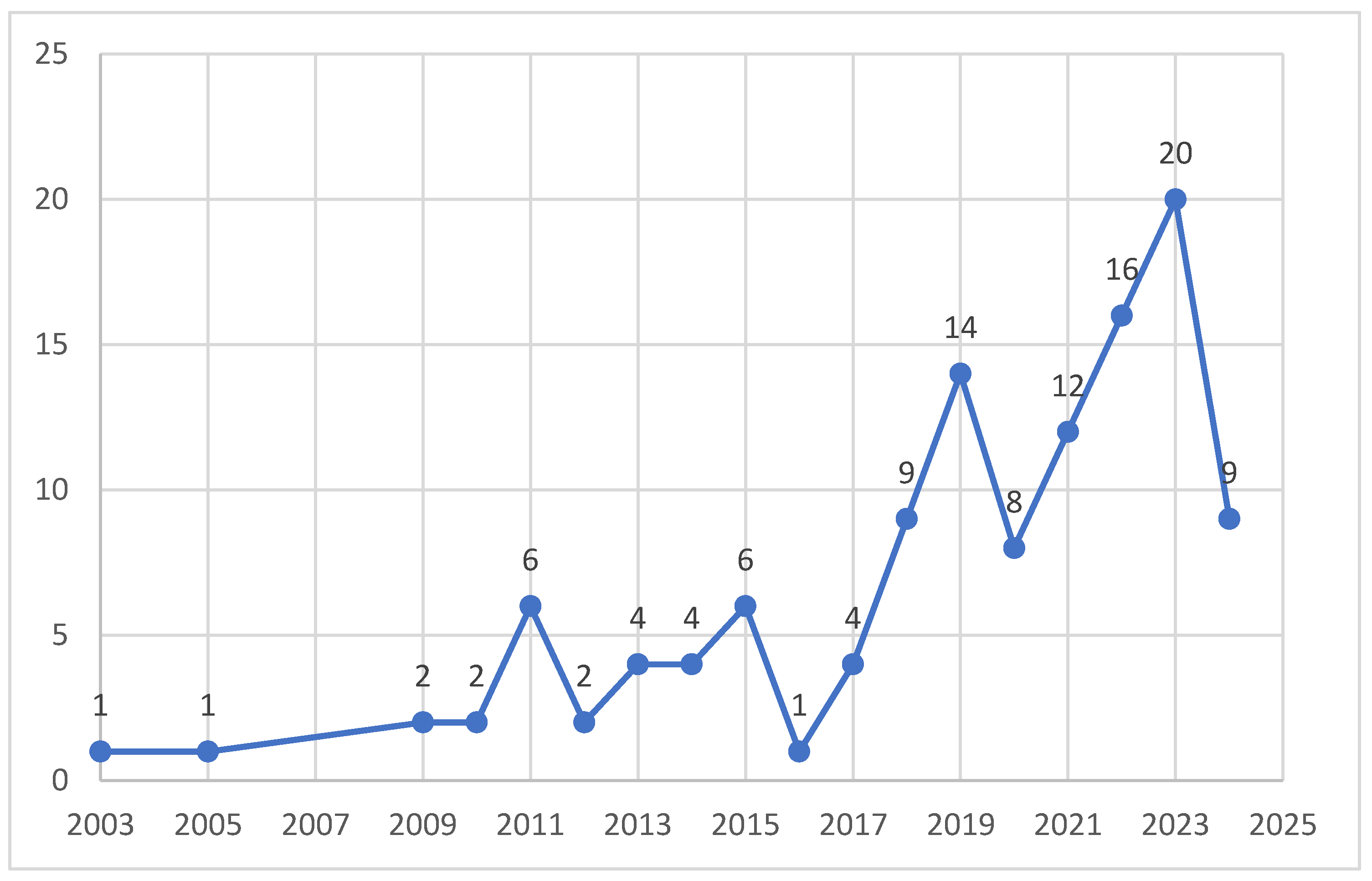

5. Bibliometric Overview

A preliminary bibliometric analysis was conducted on the final pool of 121 articles to contextualize the emerging research landscape of female entrepreneurship in the GCC. The temporal distribution of publications spanning from 2003 to 2024 illustrates a growing scholarly interest over time, with notable surges in the number of studies appearing in the last five years (

Figure 3). This upward trend not only reflects an evolving focus on female entrepreneurial activity and supportive policy initiatives within the GCC but also aligns with global dynamics. In this context, research on female entrepreneurship has experienced considerable growth worldwide, as highlighted by Cardella et al. [

82], with the number of published studies rising from 61 in 2006 to 381 in 2019.

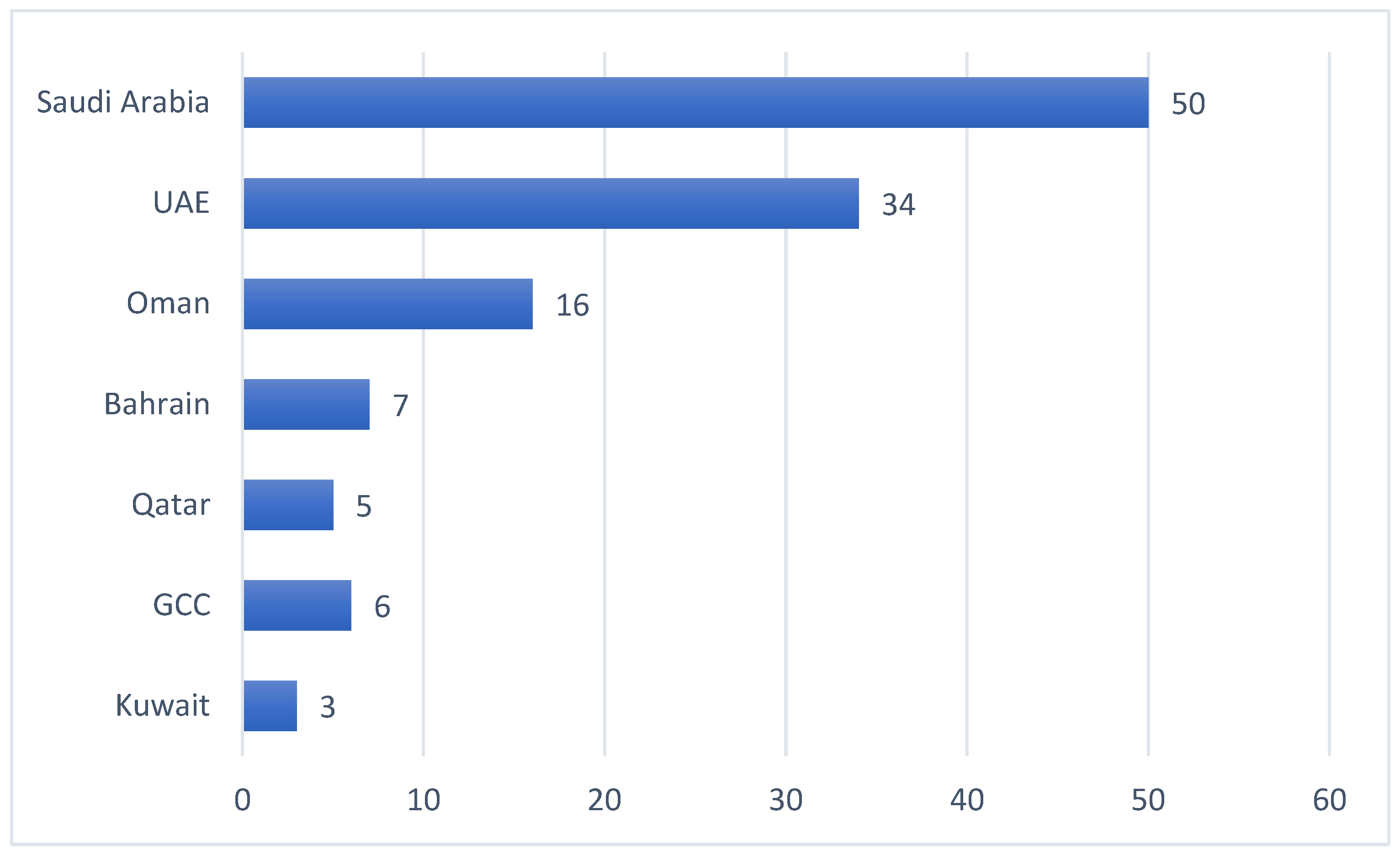

Geographically, Saudi Arabia is the most examined context (

Figure 4), suggesting that its substantial market size, regulatory reforms, and ongoing sociocultural transformations may render it a focal point for scholars exploring women’s entrepreneurial involvement. The United Arab Emirates closely follows, demonstrating the nation’s prominent initiatives to promote innovation and entrepreneurship, hence increasing academic focus on female-led enterprises. Other GCC nations, including Oman, Qatar, and Bahrain, are represented to a lesser extent, indicating potential chances for a more equitable and comparable analysis throughout the region.

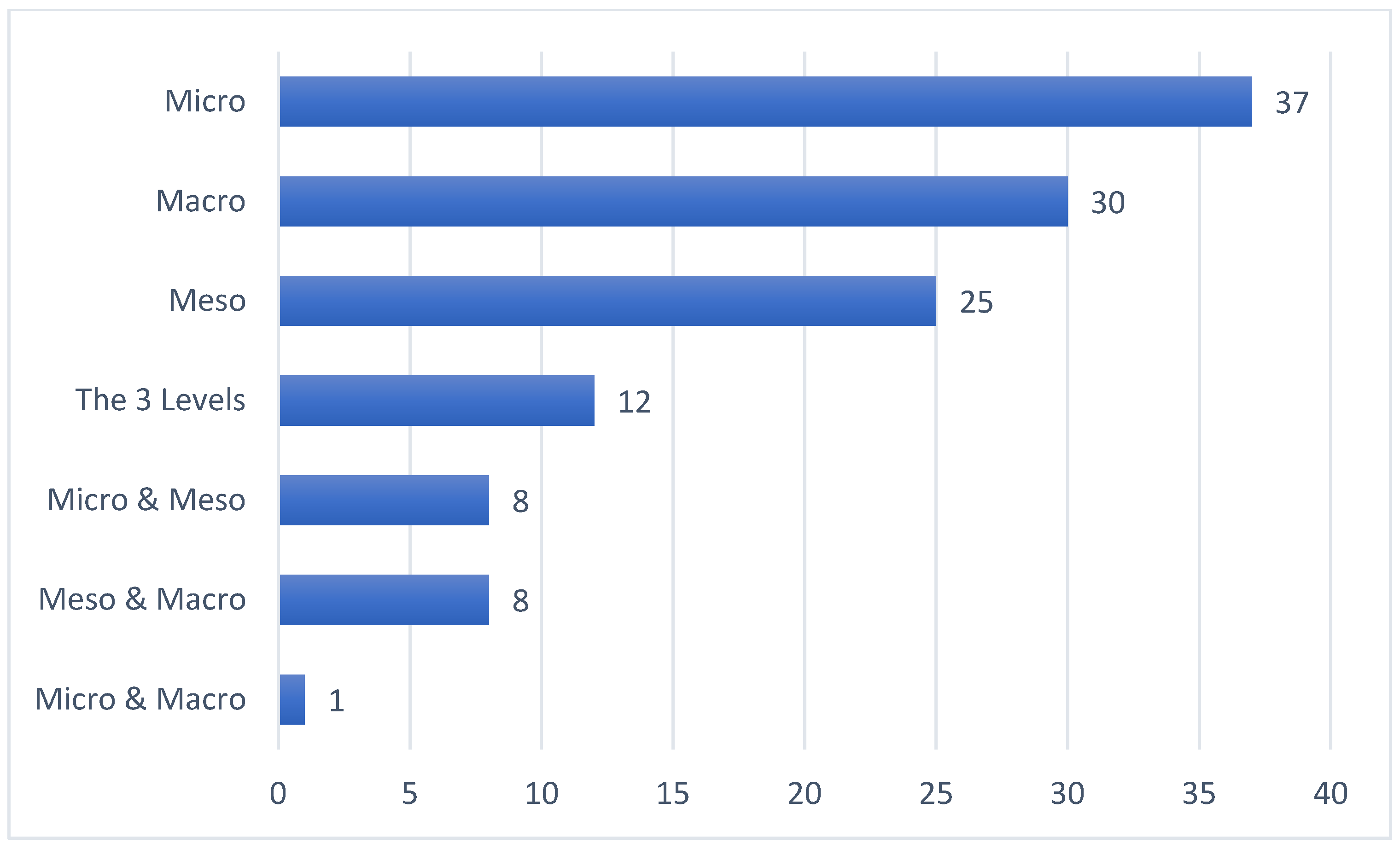

Analysis of the primary level in the selected papers indicates a fairly uniform distribution across micro-, meso-, and macro-components. Of the retained publications, 37 concentrate on the micro-level, 30 on the macro-level, and 25 on the meso level, however, few research incorporate various levels of study (

Figure 5). This distribution reveals that the current literature predominantly exhibits a singular focus, highlighting a deficiency in comprehensive, multi-faceted research.

The results in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 highlight a significant gap in existing literature, as it limits the understanding of the factors influencing female entrepreneurship in the GCC to either a single perspective or a single country. Our literature review addresses this gap by offering a comprehensive overview of the various factors at all levels impacting female entrepreneurship across all GCC countries. Addressing this gap is essential for enhancing the overall understanding of the interlinked dimensions and multiple factors influencing female entrepreneurship in the GCC. By reviewing studies from the entire region, this SLR aims to provide a broader, more nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics at play.

The variety of journal sources and outlets (

Table 1)—spanning entrepreneurship-focused publications to those in disciplines like as gender studies, management, and organizational research—indicates the multidisciplinary character of this academic topic. Although certain journals (e.g., International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, Sustainability) are cited more often, the distribution across diverse outlets indicates that female entrepreneurship research in the GCC remains relevant to a wide range of academic communities, thereby underscoring the multifaceted nature of the field.

6. Analysis of Female Entrepreneurship in the GCC: Employers, Self-Employed, and Own-Account Workers

This section presents an analysis of female entrepreneurship in the GCC, based on ILO data from 2014 to 2022, focusing on four key economic roles: contributing family workers, employers, self-employed individuals, and own-account workers. The analysis highlights significant trends in women’s participation across these categories, explores the rise in women’s engagement in family-owned enterprises, the leadership roles of female employers, and the increasing autonomy of self-employed women.

6.1. Females Contributing Family Workers

Women engaged in family-owned enterprises without direct remuneration play a crucial yet undervalued role in the Gulf region. Between 2014 and 2022, the trends varied significantly across countries. In the UAE, the percentage of women in such roles grew rapidly from 24.37% in 2014 to 76.52% in 2019, before declining to 46.55% in 2022, likely reflecting broader socio-economic changes. Kuwait saw a steady increase, reaching 44.98% by 2022, indicating gradual progress in inclusion. In Saudi Arabia, the proportion rose notably from 17.76% in 2014 to 46.36% in 2022, driven by the transformative Vision 2030 reforms. Meanwhile, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman experienced stable patterns with minimal increases, highlighting differing trajectories across the region.

6.2. Female Employers

Women in leadership roles within formal businesses have experienced varied progress across the Gulf region. Bahrain has consistently led in this area, with the proportion of women in leadership rising from 27.59% in 2014 to 36.78% in 2022. Saudi Arabia witnessed the most dramatic growth, increasing from 4.42% to 44.96%, largely driven by Vision 2030 initiatives aimed at empowering women. In Kuwait, the percentage grew to 28.59%, reflecting expanded entrepreneurial opportunities for women. Qatar and Oman saw moderate increases, reaching 30.87% and 21.43%, respectively, by 2022. By contrast, the UAE experienced stagnant growth, with only a slight rise to 9.69% over the same period.

6.3. Self-Employed Women

Self-employment reflects women’s autonomy in business, bridging the gap between informal and formal entrepreneurship. Bahrain leads in this area, with a gradual increase from 25% in 2014 to 30.42% in 2022, demonstrating steady progress in fostering women’s entrepreneurial activity. Saudi Arabia experienced substantial growth, with the proportion rising from 6.11% to 42.88%, driven by reforms aimed at enhancing women’s economic roles. Oman and Qatar saw moderate growth, reaching 24.18% and 22.16%, respectively. In contrast, the UAE and Kuwait showed limited progress, with modest increases to 13.8% and 9.58%, highlighting slower advancements in self-employment opportunities for women.

6.4. Own-Account Workers

Women running businesses without employees demonstrate a shift toward formal entrepreneurship across the Gulf region, with varying levels of progress. The UAE saw significant growth, reaching 20.32% by 2022. Saudi Arabia recorded the largest increase, rising from 6.69% to 36.03%, driven by economic reforms supporting women’s entrepreneurship. Oman and Qatar experienced incremental progress, with proportions reaching 21.88% and 6.18%, respectively. In Bahrain, the percentage remained stagnant at around 11%, while Kuwait showed minimal activity, with figures remaining below 1%, reflecting limited engagement in this form of business ownership.

In summary, the analysis of female entrepreneurship in the GCC highlights progress and challenges across economic roles. Women’s participation has increased, particularly in Saudi Arabia, driven by Vision 2030 reforms. Saudi Arabia and Bahrain lead in female employers and self-employment, while Kuwait and the UAE show slower growth. However, the UAE saw notable gains in own-account workers, indicating a shift toward formal entrepreneurship. Persistent gaps remain, especially in undervalued roles like contributing family work and in ensuring broader inclusivity and access to resources. This analysis underscores the evolving landscape of female entrepreneurship in the region, revealing both progress and areas where further support is needed to foster greater gender parity in business ownership and leadership.

7. Entrepreneurial Trends in the GCC: Sectoral Focus, Job Creation, and Gender Dynamics

This section examines entrepreneurial trends in the GCC using GEM data, focusing on sectoral distribution, job creation dynamics, and gender-based disparities. It analyzes the spread of entrepreneurial activities across sectors, assesses the role of ventures in job creation, and explores gender-related trends within the entrepreneurial landscape.

7.1. Sectoral Distribution of Entrepreneurial Activities

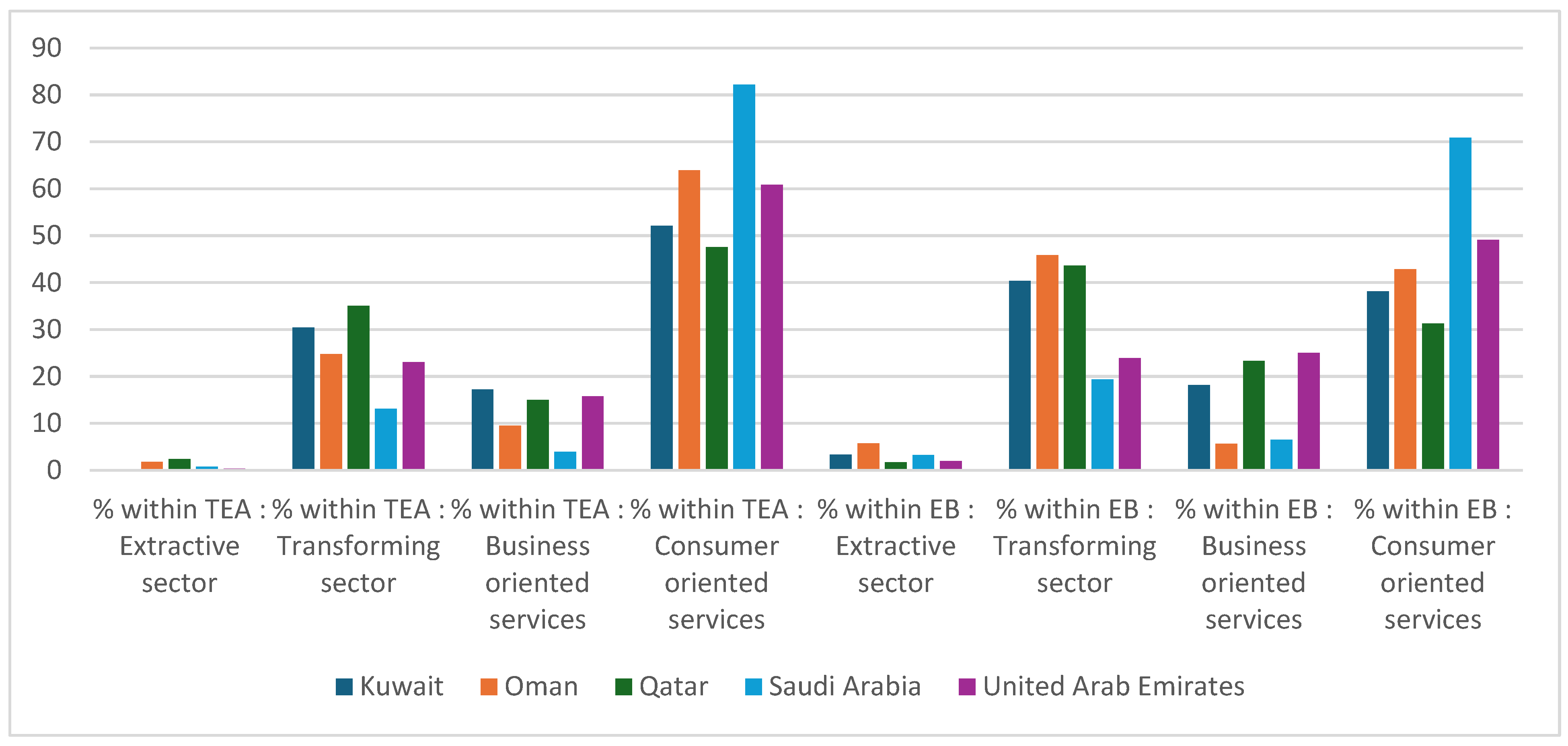

An analysis of Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) and Established Businesses (EB) for the year 2020 (chosen because it provides the most comprehensive data available for the GCC) using GEM data highlights sectoral trends across five GCC countries (excluding Bahrain due to data unavailability) (

Figure 6). The findings underscore the dominance of consumer-oriented services and the pressing need for policies to foster entrepreneurship in underrepresented sectors, such as extractives. Consumer services overwhelmingly dominate both TEA and EB, with Saudi Arabia leading in percentages, positioning this sector as the primary driver of entrepreneurship in the region. The transforming sector demonstrates moderate representation, with higher activity levels observed in Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar. Conversely, the extractive sector sees minimal entrepreneurial involvement, reflecting its capital-intensive nature and the limited opportunities it offers for small-scale entrepreneurs.

7.2. Entrepreneurial Activity and Job Creation

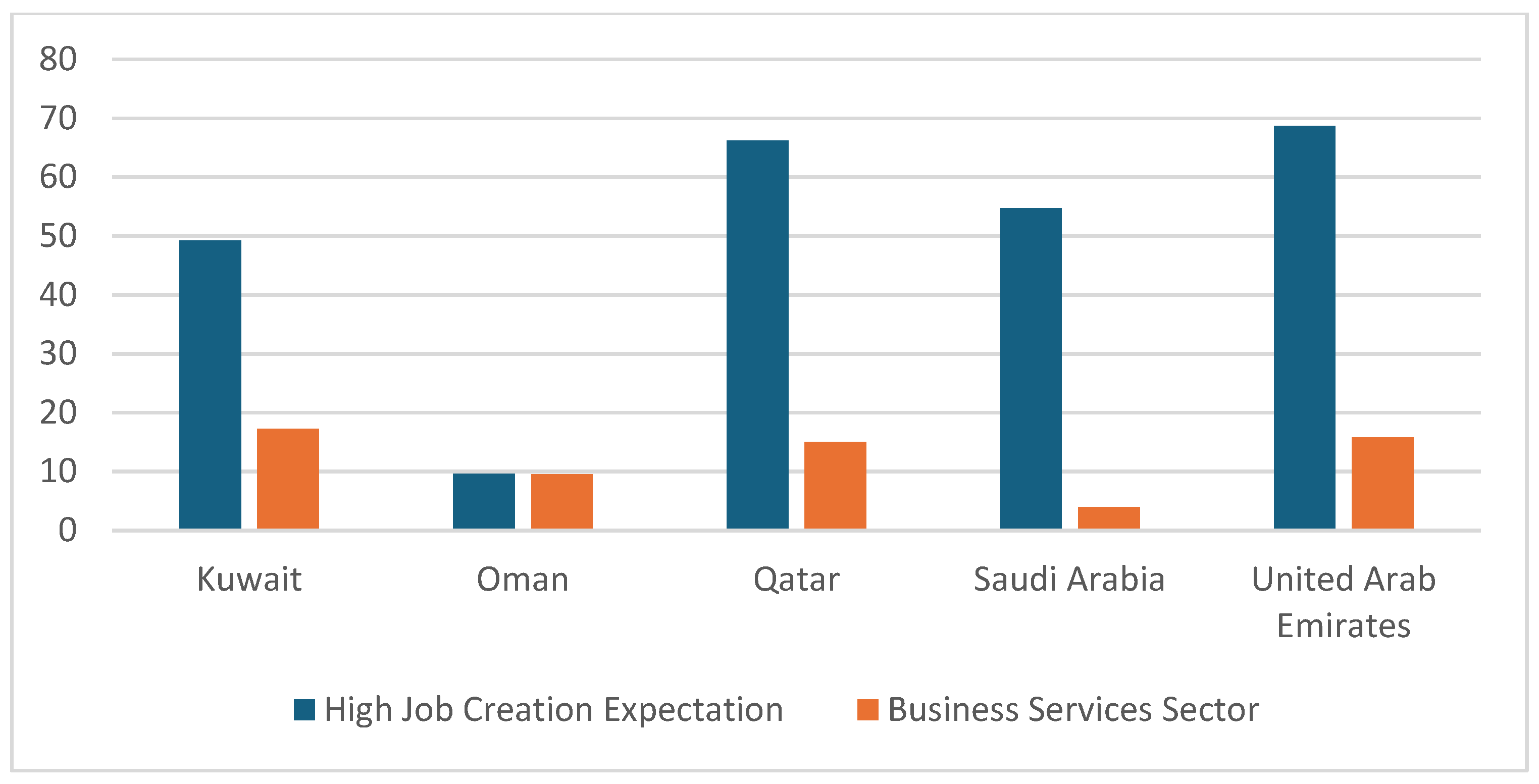

Key trends in entrepreneurial activity highlight a focus on ventures with high employment potential, while underscoring the need to develop underrepresented sectors like business services to strengthen regional economic ecosystems (

Figure 7). High job creation expectations are prominent across all countries, with Qatar and the UAE leading, reflecting an emphasis on scaling businesses and generating employment in alignment with economic diversification goals. However, the business services sector shows low representation, particularly in Saudi Arabia, indicating significant untapped opportunities for growth in this critical area.

7.3. Gender Distribution of Entrepreneurial Activity

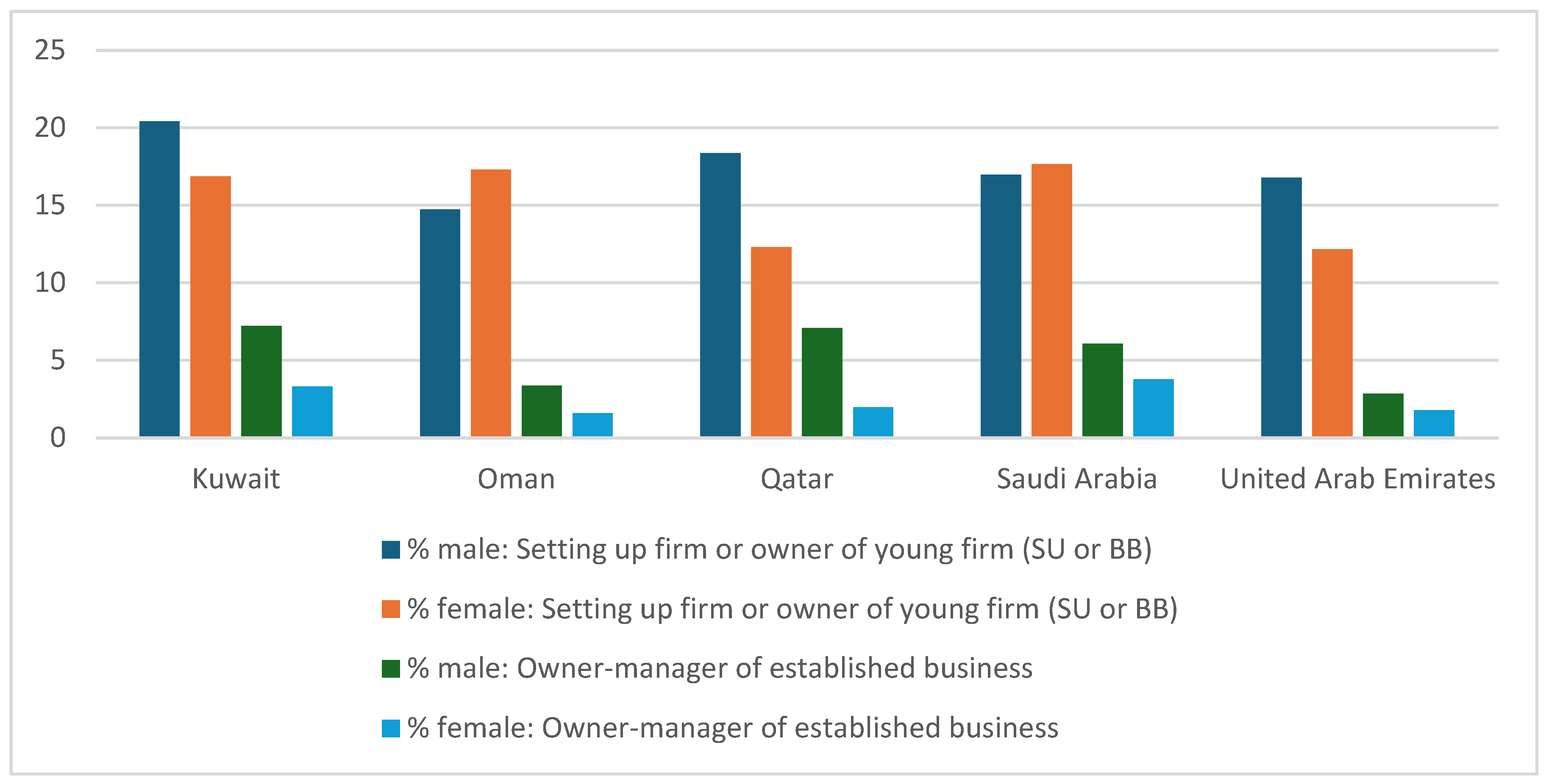

Gender dynamics in entrepreneurial activity reveal both progress and persistent gaps (

Figure 8). In early-stage entrepreneurship, the gender gap is relatively small in countries like Kuwait, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, where women actively set up or own young firms at rates comparable to men, reflecting growing female participation in startup ecosystems. However, a more pronounced gender gap is evident in established businesses, with male entrepreneurs dominating this category across all countries. Female participation is particularly low in Qatar, while both genders exhibit minimal involvement in the UAE. These trends highlight notable progress in women’s engagement in early-stage entrepreneurship but point to structural or systemic barriers limiting their advancement to leadership roles in established businesses. This underscores the need for targeted support to help women scale their ventures sustainably.

In sum, entrepreneurial trends in the GCC reveal a dominance of consumer-oriented services in early-stage (TEA) and established businesses, particularly in Saudi Arabia, while sectors like extractives and business services remain underdeveloped. Job creation expectations are strong, with Qatar and the UAE leading efforts to scale businesses and diversify economies. Gender dynamics show narrowing gaps in early-stage entrepreneurship, especially in Kuwait, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, but a significant gender gap persists in established businesses, particularly in Qatar and the UAE. These findings emphasize the importance of fostering sectoral diversity and addressing systemic barriers to create a more balanced and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem across the region.

8. Systematic Literature Review of Female Entrepreneurship in the GCC: A Multi-Level and Institutional Lens

The primary analysis of quantitative data from the ILO and GEM reveals significant trends and disparities, underscoring that the entrepreneurial landscape for women in the GCC is shaped by multifaceted challenges and opportunities. To gain a comprehensive understanding, a systematic literature review is essential, one that examines individual, structural, and cultural dynamics alongside broader institutional factors influencing the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The intersection of entrepreneurship and sustainability is increasingly gaining attention, yet studies specifically focusing on the GCC remain limited. Apostu and Gigauri [

8] examined the relationship in emerging countries through bibliometric analysis and panel regression models, confirming growing interest in how entrepreneurship influences sustainable development goals (SDGs). Fernández et al. [

11] analyzed studies linking female entrepreneurship to sustainability, emphasizing women’s awareness of sustainability when launching ventures and calling for further research, while Bastian et al. [

34] sought to consolidate fragmented research on female entrepreneurship in the MENA region.

Recent studies underscore the critical interplay between socio-cultural, institutional, and sustainability factors shaping entrepreneurship, particularly for women in the Gulf and MENA regions. Al Boinin [

41] highlights the influence of socio-cultural factors on women’s entrepreneurial experiences in the Gulf through a systematic analysis of 65 articles. Hattab [

83] provides insights into entrepreneurial activity rates, orientations, demographics, and enterprise characteristics of women entrepreneurs in the MENA region. Similarly, Aljuwaiber [

32] conducted a literature review identifying three main themes—female entrepreneurship and gender, youth entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial behavior. Hashim [

40] focuses on the unique contextual challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in the Arab Gulf States, such as family structures, market arrangements, and cultural and religious norms, advocating for a region-specific understanding of entrepreneurship.

The literature highlights the critical importance of adopting a holistic, multi-level approach to address existing research gaps in female entrepreneurship and sustainability. Our systematic review reveals that, of the 121 studies analyzed, only 11 incorporate a multi-level framework. Moreover, while only five studies explore the intersection of female entrepreneurship and sustainability, none explicitly apply a multi-level analysis rooted in an institutional perspective (

Table 2).

Research focusing on Qatar underscores the significance of meso-level support systems in fostering female entrepreneurship. Al-Mulla et al. [

84] identify limited access to capital and networks as key obstacles for Qatari entrepreneurs, while Al-Qathani et al. [

19] highlight the contributions of female-led ventures to sustainability efforts but note that persistent socio-cultural barriers continue to impede their progress. This study further emphasizes the critical role of government policies and funding programs in supporting female entrepreneurs and promoting economic diversification. Both studies highlight the importance of national strategies and policies, as well as socio-cultural influences, in shaping the entrepreneurial landscape.

In Saudi Arabia, Abdelwahed et al. [

7] argue that education is pivotal in equipping female entrepreneurs with the skills necessary to promote sustainability, stressing that government economic initiatives and national strategies are essential for sustaining their efforts. Similarly, Abdelwahed and Alshaikhmubarak [

85] highlight the role of micro-level factors such as competence, mindset, and intentions, illustrating how individual capabilities interact with broader systemic support mechanisms to drive entrepreneurial success.

In Bahrain, Alsaad et al. [

86] examines the multidimensional factors influencing female entrepreneurship, including education, supportive policies, and socio-cultural norms. The study underscores the need to address challenges at both macro and meso levels to effectively empower female entrepreneurs and advance sustainable development.

Collectively, these studies reveal that while female entrepreneurship is widely recognized as a driver of sustainability, realizing its full potential requires a comprehensive, multi-level approach. This involves addressing micro-level motivations and competencies, meso-level institutional support systems, and macro-level socio-cultural and policy environments. Such an approach is essential for identifying the factors that enable or hinder women’s contributions to sustainability through entrepreneurship. Expanding this research to cover a broader range of GCC countries is crucial for developing more targeted, context-specific strategies to empower female entrepreneurs as agents of sustainable economic development.

On the one hand, only five studies explicitly explore the link between female entrepreneurship and sustainability, particularly sustainable economic development within the GCC context. On the other hand, most studies in this SLR focus on factors influencing female entrepreneurship, but they do not necessarily adopt a comprehensive approach that identifies challenges and opportunities across the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels using an institutional lens. These studies collectively underscore the pivotal role of female entrepreneurs in advancing sustainability across the GCC. At the same time, they highlight the diverse factors that shape women’s entrepreneurial journeys, reinforcing the need for holistic strategies to unlock their potential for sustainable impact. Building on these insights, we propose a conceptual framework that integrates both multi-level and institutional perspectives, as recommended by Naguib and Jamali [

39], while expanding the geographic scope to encompass the GCC region. By adopting this comprehensive approach, future research can more effectively capture the complex, interconnected dynamics shaping female entrepreneurship in the region.

Evidently, as both existing research as well as ILO and GEM data presented in this study demonstrate, female entrepreneurs are essential contributors to sustainable economic development. However, to unlock their full potential, a thorough understanding of the enabling and constraining factors influencing their activities is required. To address this gap, we based the analysis on the proposed holistic framework grounded in an institutional perspective.

In this section we present the results of the systematic literature review conducted on female entrepreneurship in the GCC, synthesizing the most significant motivations and challenges across micro-, meso-, and macro-levels along with the corresponding institutional pressure mechanisms and dimensions. This systematic approach allows for a holistic and structured analysis of the entrepreneurial landscape, shedding light on the complex interplay of individual, institutional, and societal factors along with the cognitive, regulative and normative dimensions that shape women’s participation in entrepreneurial activities in the region through mimetic, coercive, and normative pressures. Through a series of graphs serving as a visual summary of the literature’s key insights, we seek to reinforce its arguments and highlighting the interconnected nature of challenges and opportunities in the GCC’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. By aligning these observations with the literature’s multilevel analysis, the review provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing female entrepreneurship, offering a robust foundation for policy recommendations and future research.

8.1. Micro-Level Analysis: Individual Challenges and Opportunities

At the individual level, cognitive frameworks shape decision-making processes by influencing how entrepreneurs perceive opportunities, evaluate risks, and develop strategies. This aligns with cognitive legitimacy, which emphasizes shared mental models and understandings. The cognitive dimension guides what is considered rational or appropriate within an environment, affecting approaches to risk, innovation, and success [

26,

46]. Mimetic pressures further influence entrepreneurial behavior, as individuals often imitate others in navigating uncertainty [

42]. Shared cognitive models act as a “lens” through which entrepreneurs interpret their environment, shaping actions, strategies, and perceptions of success or failure [

26].

The literature review emphasizing the individual factors, shows that female entrepreneurs face personal and psychological hurdles, including risk aversion, fear of failure, the necessary education and skills, and the dual burden of balancing family and business responsibilities [

36,

87,

88]. Socio-cultural expectations often exacerbate these issues, limiting entrepreneurial decision-making and activities [

89,

90,

91]. Women in the GCC often exhibit a reluctance to engage in high-risk ventures due to fear of failure and societal judgment [

92,

93], particularly in male-dominated industries where patriarchal norms persist [

91,

94]. Additionally, the lack of necessary education and entrepreneurial literacy and skills further constraint women’s ability and autonomy in running businesses [

95,

96,

97]. Familial expectations regarding women’s caregiving roles also create significant challenges, leaving them with limited time and resources to invest in their businesses [

98,

99]. Women often depend on family support systems to navigate these dual responsibilities, which might not always be possible [

100]. Despite these challenges, intrinsic motivations like economic independence, self-fulfillment, and societal contributions drive many women to pursue entrepreneurship [

88,

101]. This resilience is particularly evident in contexts where women balance professional and personal aspirations while achieving financial stability [

102,

103] and are equipped with the necessary skills and education for entrepreneurial endeavors [

104].

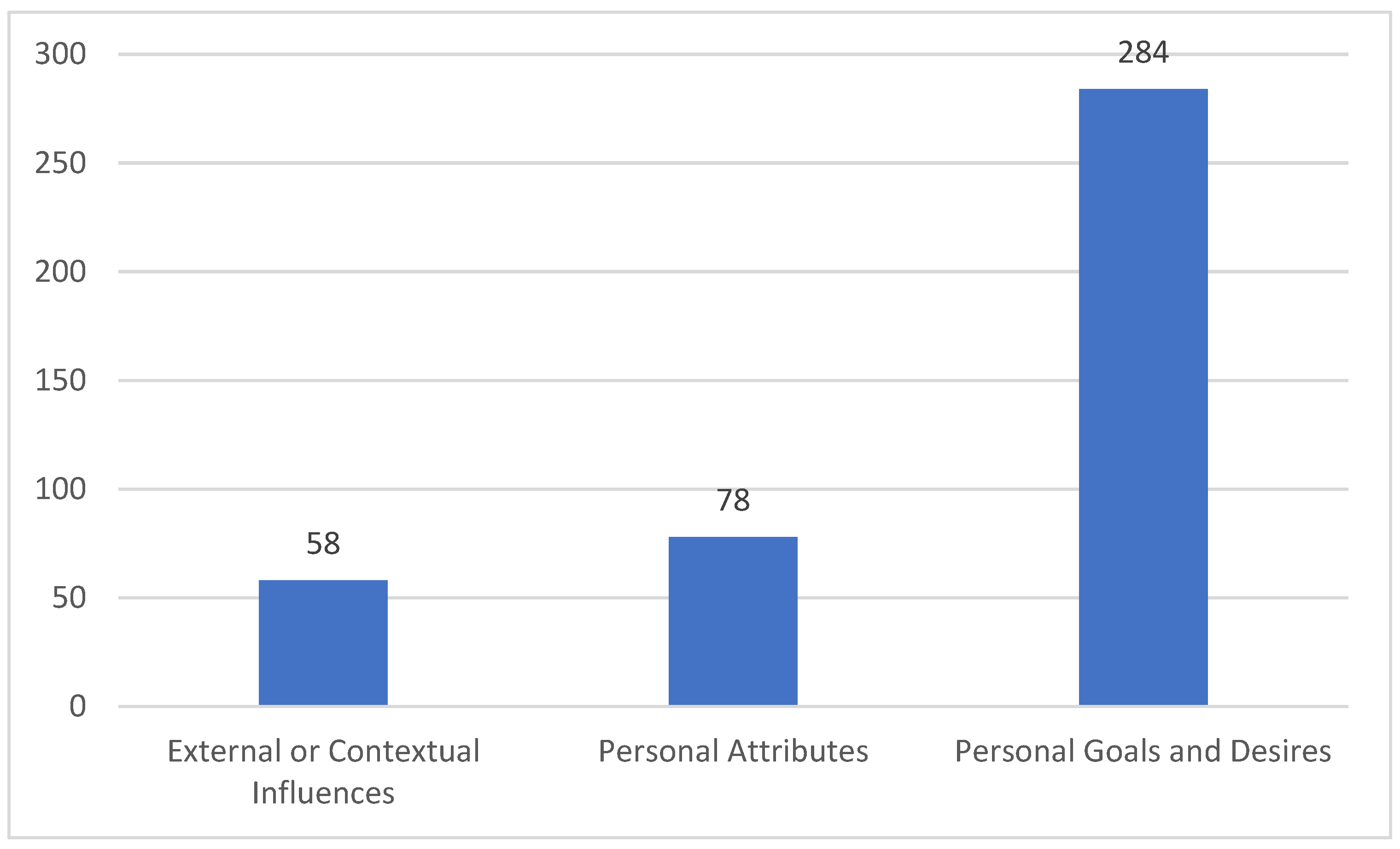

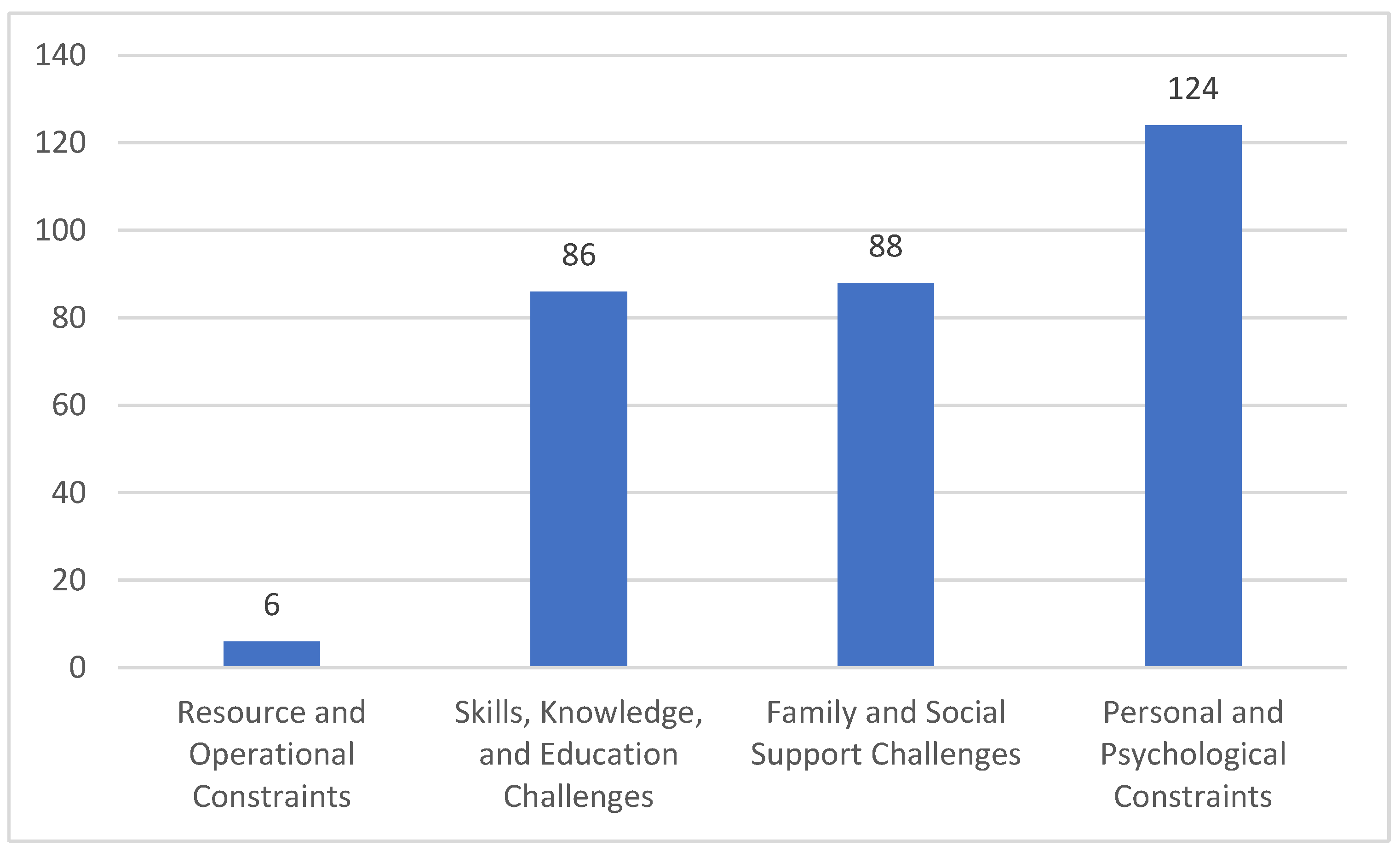

The main themes of motives at the micro-level show personal goals and desires ranking the highest, followed by personal attributes, and then external or contextual influences (

Figure 9). The literature highlights that independence is the most significant motivator driving women to entrepreneurship, followed by family support, the desire for personal growth, work-life balance, and having the necessary education and skills (

Figure 10). These findings reflect the growing aspirations of women to achieve autonomy and economic agency while balancing professional ambitions with family responsibilities. Intrinsic motivations, such as self-fulfillment, and the ability to contribute to society, further underscore the personal significance that entrepreneurship holds for many women in the region. These observations resonate with the literature, which emphasizes that personal attributes and motivations drive women to entrepreneurship despite societal pressures.

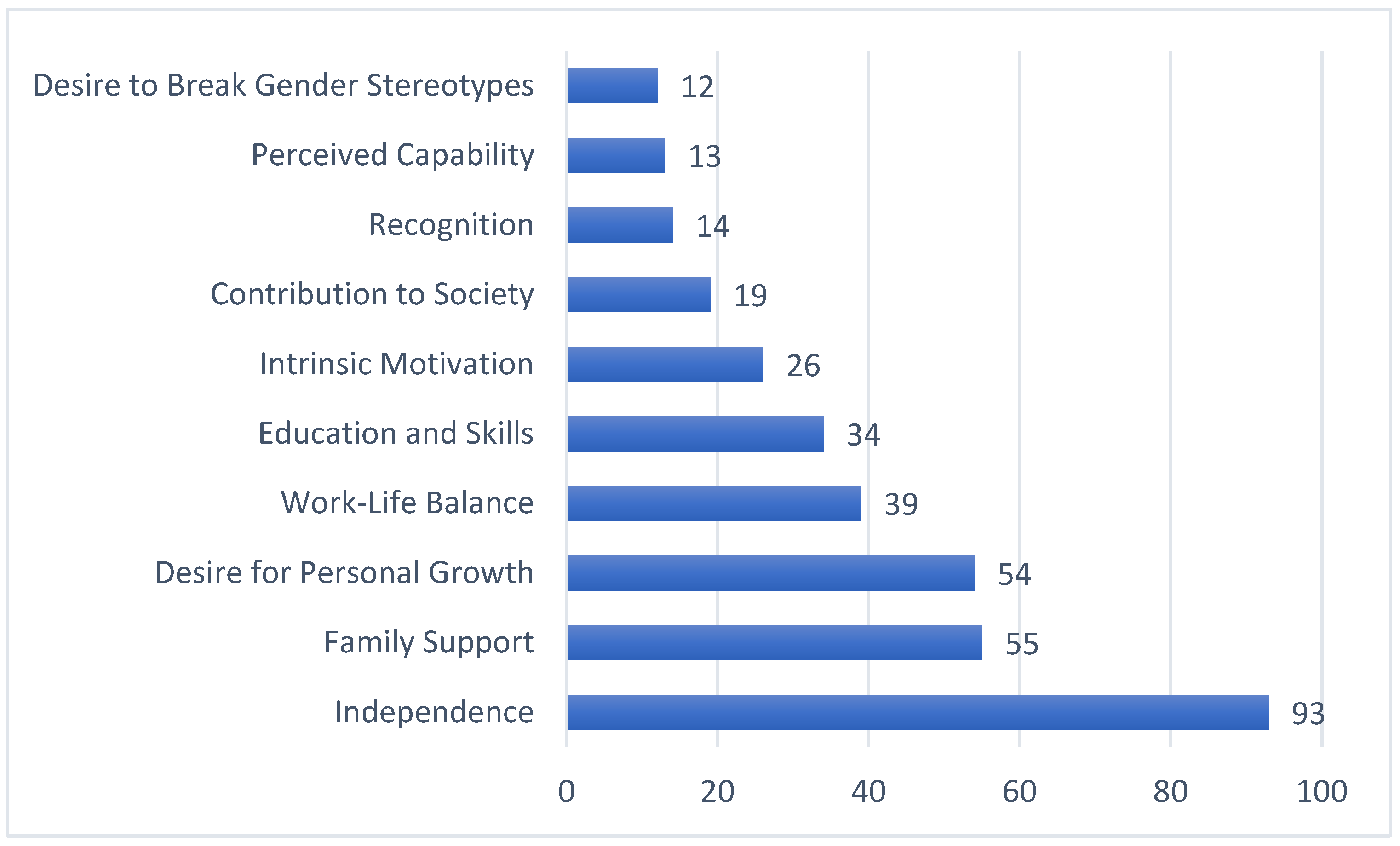

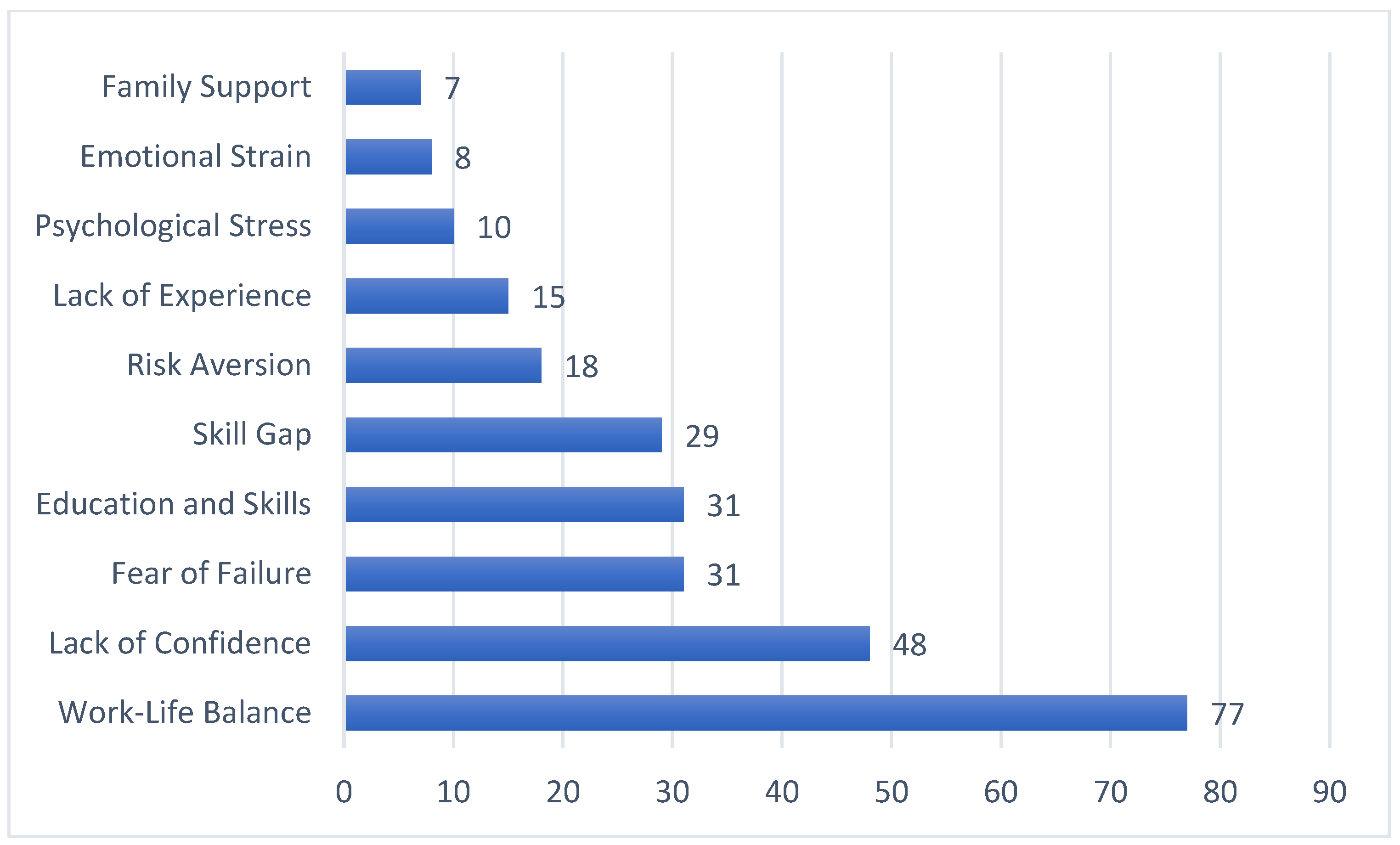

However, micro-level challenges remain pronounced, with personal and psychological constraints emerging as the most significant challenges, followed by those related to family and social support, and challenges in skills, knowledge and education (

Figure 11). A further analysis reveals that work-life balance is the most prominent challenge within the family and social support category (

Figure 12). Lack of confidence are highlighted as key issues, while fear and failure, challenges in access to education and skills development, and skill gap further constrain female entrepreneurs. The literature therefore underline that the dual burden of managing professional and familial roles is compounded by individual constraints, which often deter women from pursuing entrepreneurial ventures or scaling their businesses. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions and support systems to alleviate these barriers.

8.2. Meso-Level Analysis: Organizational-Sectoral Barriers and Support

Organizational-Sectoral barriers and support at the meso-level refer to obstacles and opportunities that emerge from the structures and practices of organizations, networks, or groups operating between the individual and the broader societal or national levels. At the organizational or sectoral level, the meso scale focuses on the structures, programs, and practices that govern industries or sectors, including legal frameworks, industry standards, and regulatory procedures that influence organizational behavior and entrepreneurial activities. The regulative dimension defines how firms operate within legal and regulatory frameworks, requiring compliance with laws related to business registration, taxation, labor, intellectual property, and environmental standards. Adherence to these rules is essential for legitimacy, operational continuity, and avoiding penalties [

42]. Coercive pressures from regulatory bodies, investors, suppliers, and customers further compel organizations to align with external expectations and industry standards [

43]. Networks play a crucial role at this level by mediating between organizations and the broader regulatory environment, fostering self-regulation, and creating context-specific frameworks that complement national laws and norms.

Therefore, at this level, systemic barriers such as limited access to professional networks and funding opportunities hinder female entrepreneurship in the GCC [

100,

105,

106]. Bureaucratic inefficiencies add to the complexity, with women facing additional regulatory hurdles compared to men [

101]. The meso-level landscape of female entrepreneurship in the GCC reveals a complex interplay of challenges and opportunities shaped by institutional dynamics. On the one hand, opportunities for women’s entrepreneurship emerge from institutional support [

97,

107], such as access to mentorship programs, networking initiatives [

85], and role models [

108], which create pathways for women to establish and expand their ventures. However, persistent challenges undermine these efforts. Persistent gaps in institutional support systems [

64], including challenges in access to capital [

109], lack of specialized training and mentorship [

110], and limited access to education tailored to entrepreneurial needs [

40,

99], restrict women’s ability to sustain long-term growth.

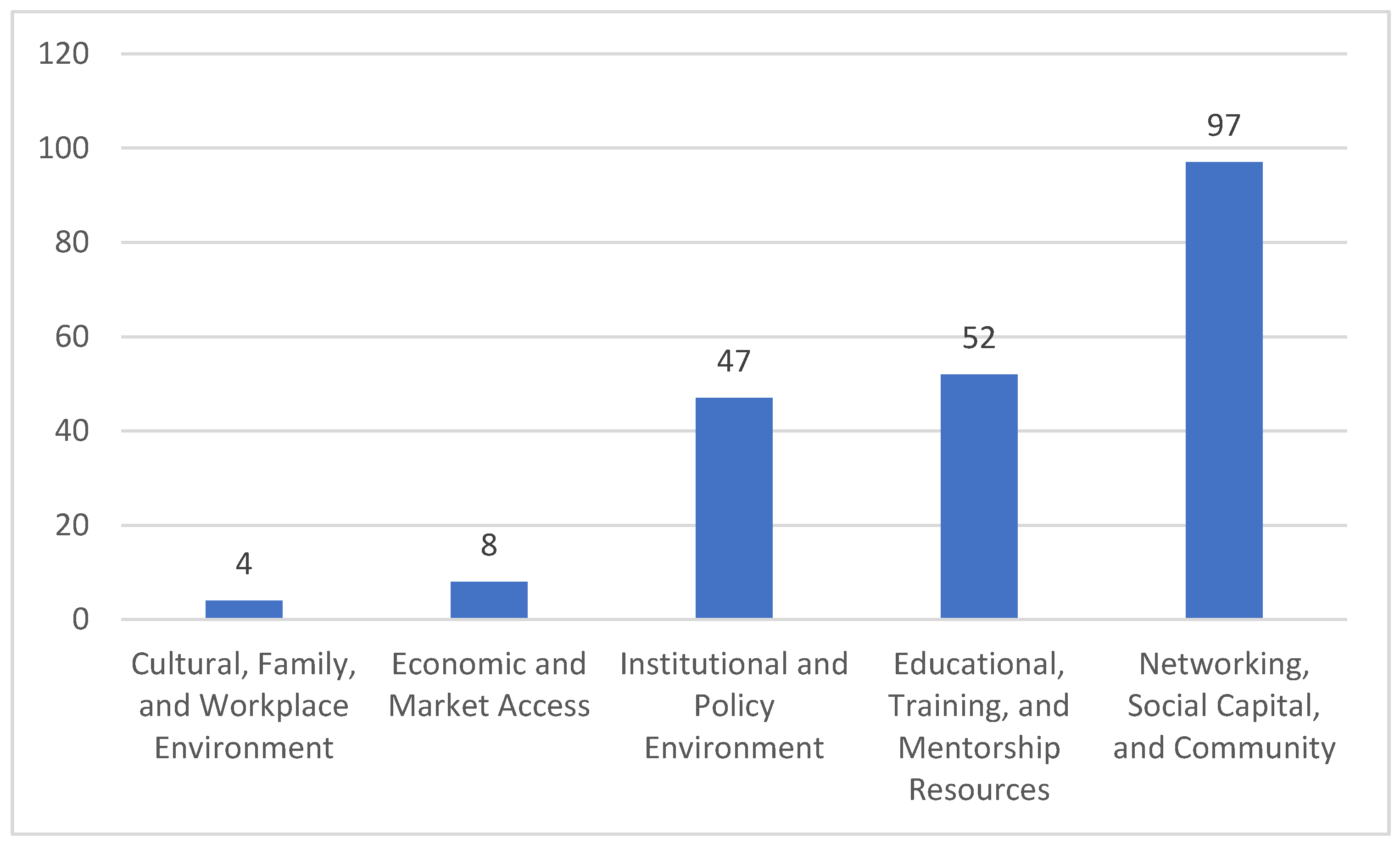

The literature identifies several pivotal enablers of female entrepreneurship including networking, social capital and community, followed by educational, training and mentorship resources, and robust institutional and policy environment (

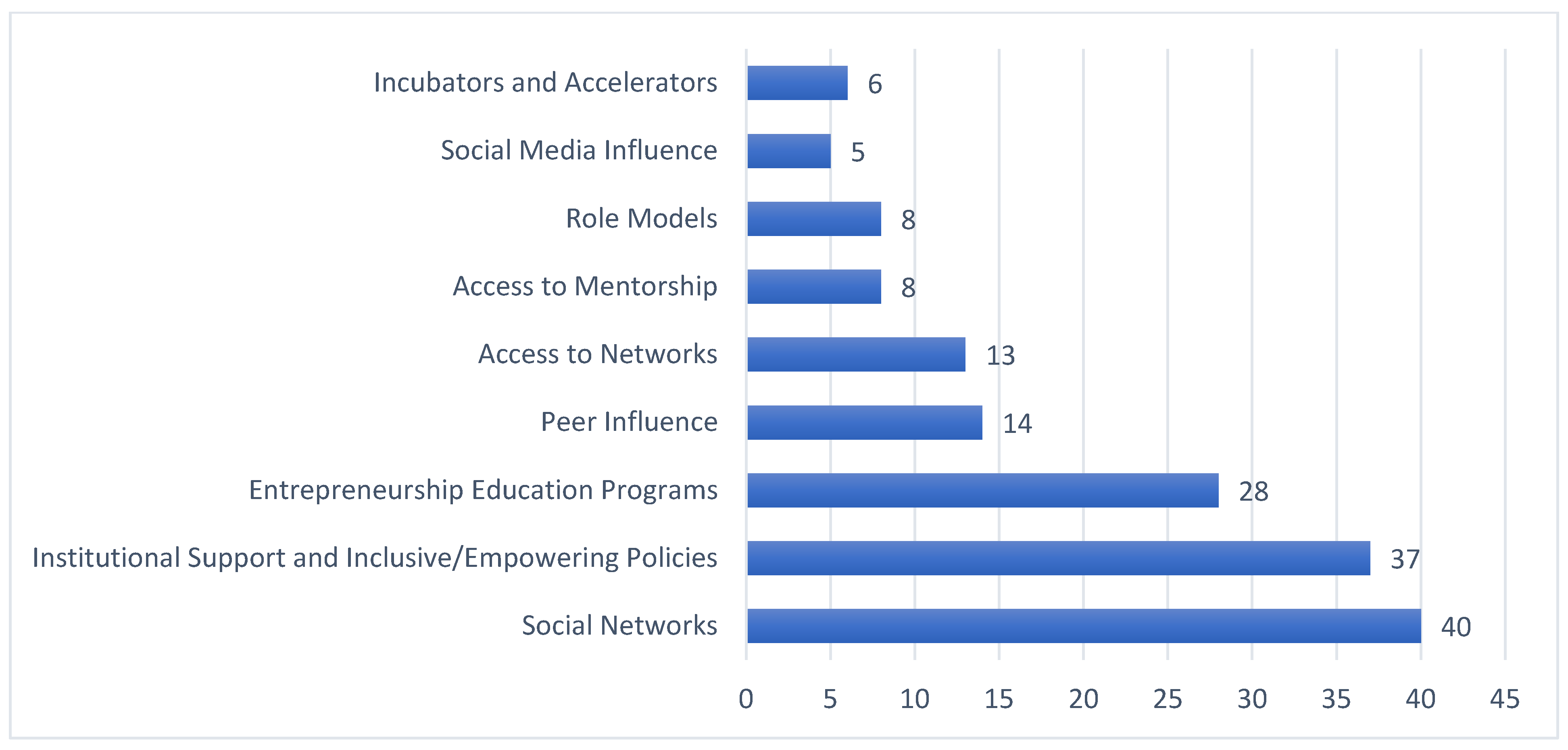

Figure 13). Furthermore, social networks, sufficient institutional support and inclusive/empowering policies, and entrepreneurial education programs appear to reinforce the critical role of a supportive ecosystem in fostering entrepreneurial ambitions (

Figure 14). Consistently, the literature review underscores the significance of tailored support mechanisms in empowering women entrepreneurs and enhancing their contributions to the entrepreneurial landscape.

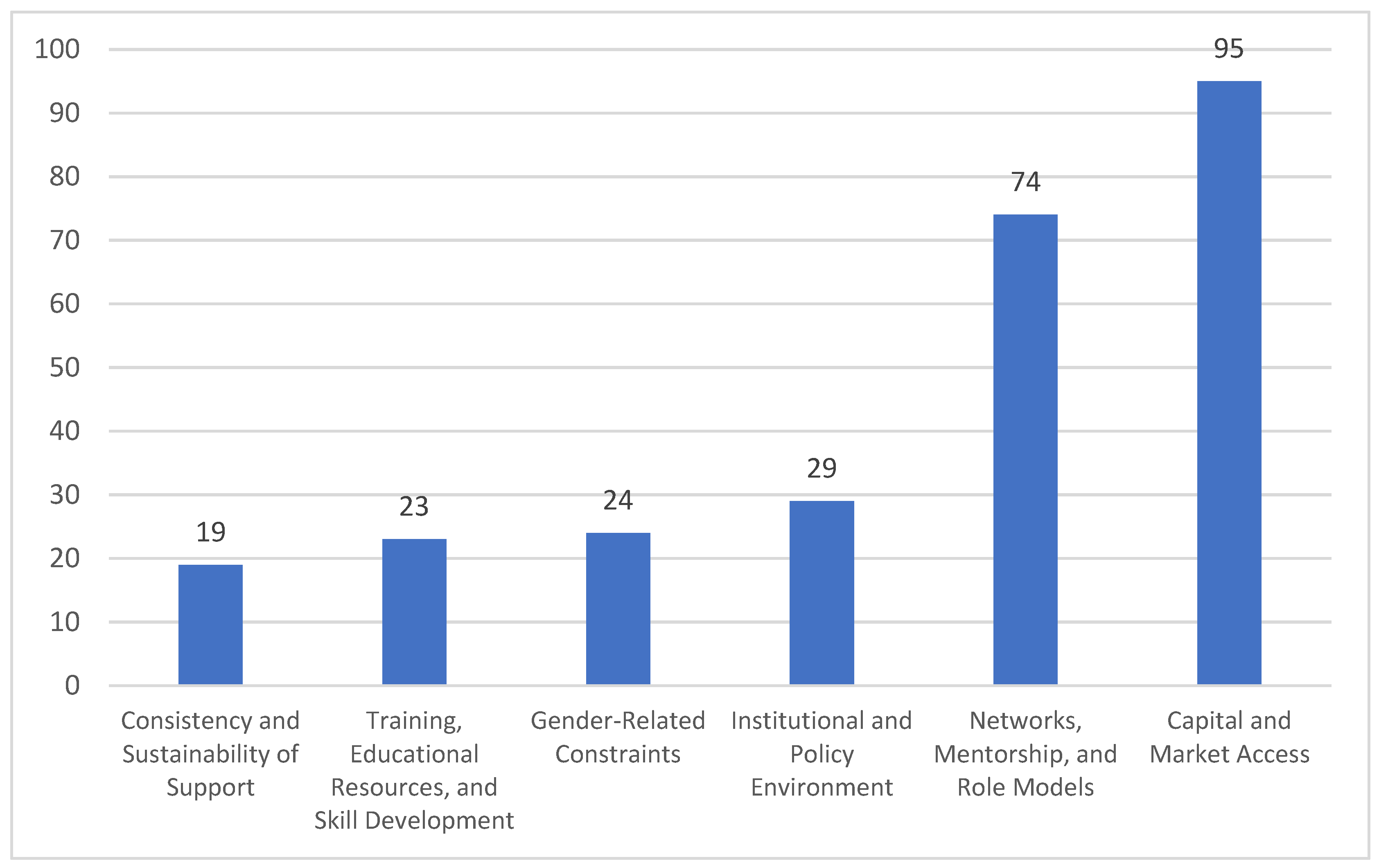

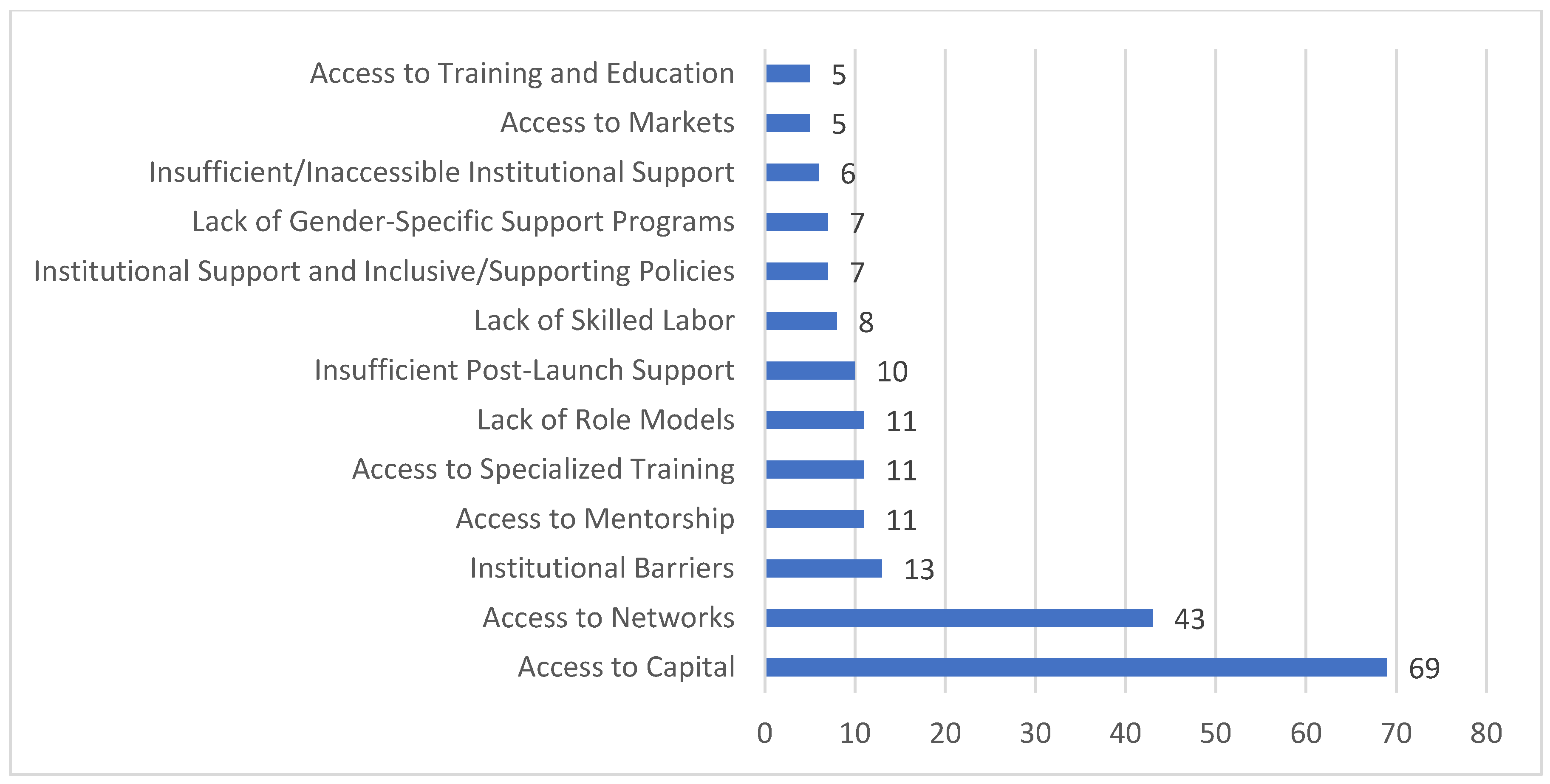

Significant challenges persist (

Figure 15) which highlights key issues such as difficulties in accessing capital and markets, the limited availability of networks, mentorship and role models, incipient institutional and policy environments, gender related constraints (such as bias and discrimination), and lack of training, education and skill development opportunities, including those specifically related to entrepreneurship. Notably, the institutional and policy environment appears to be both a motive and a challenge. This suggests that policy effectiveness in the GCC is highly context-dependent, requiring a closer examination of implementation practices, sector-specific needs, and the alignment between policy design and on-ground realities to ensure consistent and supportive outcomes. It underscores the importance of balanced and well-crafted policies that minimize challenges while maximizing motivational aspects to foster a supportive and effective environment. More specifically, barriers like restricted access to capital and access to networks are compounded by institutional hurdles, including institutional barriers, lack of access to mentorship, specialized training, and role models (

Figure 16). These challenges underscore systemic gaps within institutional frameworks, emphasizing the need for reforms to foster inclusive and gender-sensitive entrepreneurial ecosystems that enable women to navigate and thrive within these systems.

8.3. Macro-Level Analysis: Societal Factors and National Regulatory Challenges and Opportunities

At the macro level, entrepreneurship is shaped by both societal norms and values (the normative dimension) and formal, centralized structures, such as laws, constitutions and national regulatory systems and policies (the regulative dimension) that influence all sectors and organizations within a country or region. The normative dimension reflects socially accepted norms, values, and professional standards that guide ethical behavior, business practices, and entrepreneurial culture. Normative pressures encourage entrepreneurs to align with societal expectations, fostering legitimacy and social acceptance. Similarly, national-level regulative frameworks further establish overarching rules that influence entrepreneurial activities across sectors, shaping compliance and governance to ensure legitimacy.

At this level, cultural and social norms remain significant barriers for women entrepreneurs in the GCC. Traditional perceptions of gender roles often prioritize family responsibilities over professional ambitions, restricting women’s ability to allocate time and resources to entrepreneurial ventures [

19,

111]. These norms perpetuate biases against women [

66], thereby hindering their progress, development, and potential to seize opportunities [

112]. National policies and regulations, while gradually evolving, still pose obstacles [

105]. Some legal frameworks, such as male guardianship laws in certain GCC countries, impose constraints on women’s ability to independently manage businesses [

113]. Despite these challenges, recent developments and changes are creating opportunities for female entrepreneurs. Rising attention and levels of education among women and shifting societal attitudes are fostering greater acceptance of women in business [

114]. Programs like Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 are actively promoting women’s economic participation, signaling a shift toward inclusivity [

66,

93]. Additionally, government programs focusing on technological and digital advancements offer flexible avenues for women to start and scale businesses [

99]. These platforms enable women to circumvent traditional barriers by accessing global markets, building networks, and innovating with fewer resources [

94].

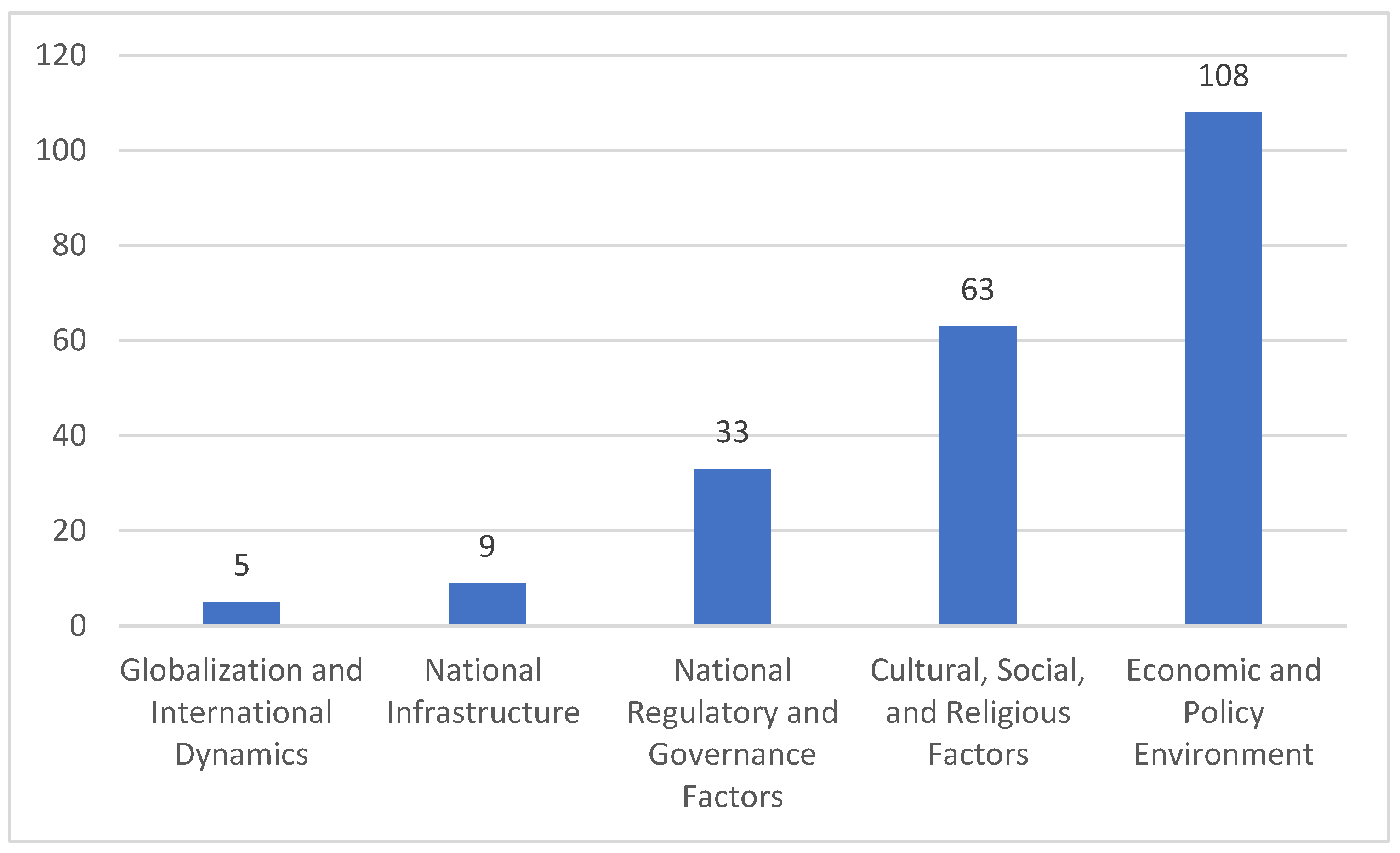

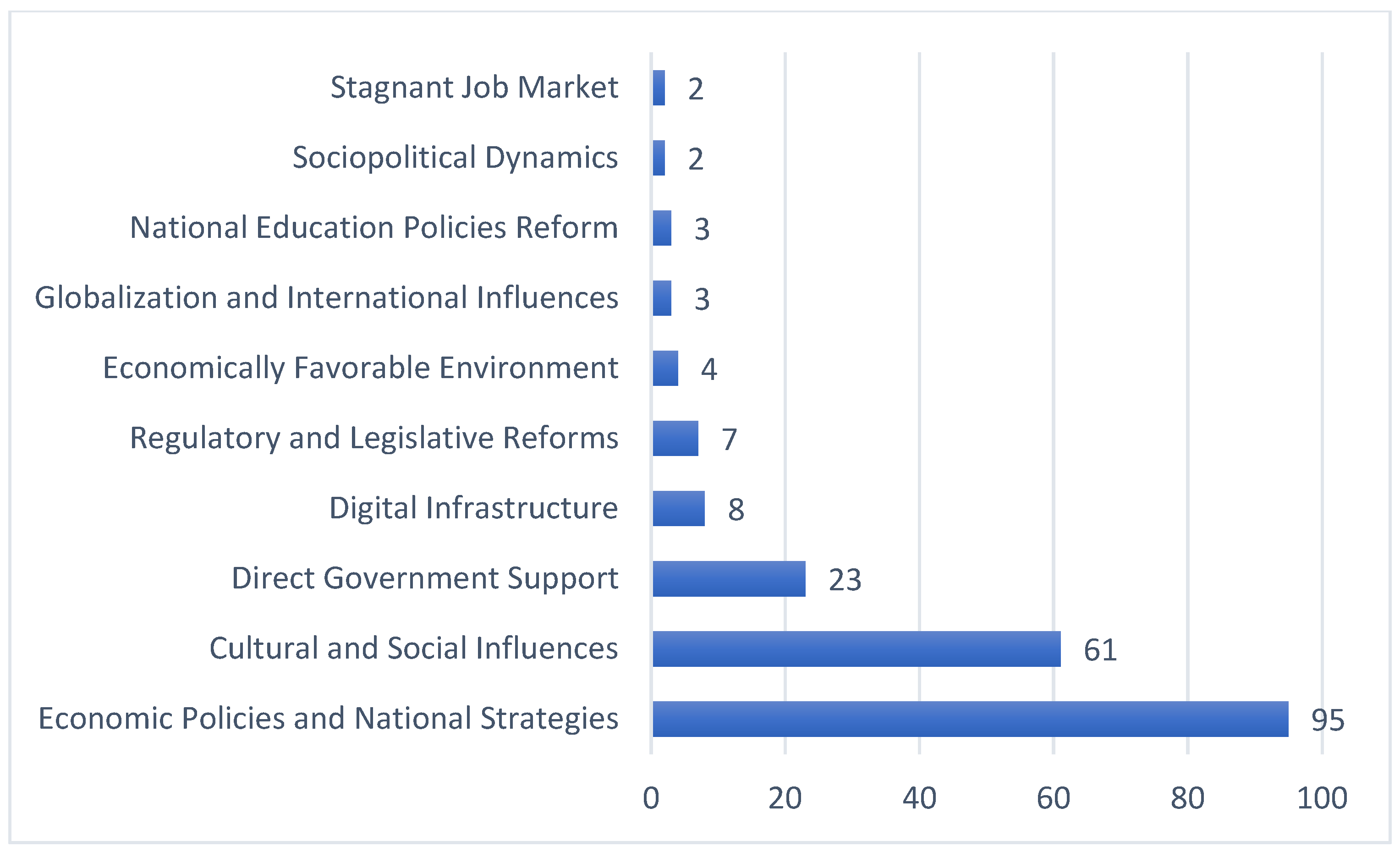

At the macro level, developed economic and policy environment followed by progressing cultural, social and religious factors as well as national regulatory and governance factors, emerge as key themes motivating female entrepreneurs (

Figure 17). Among these, economic policies and national strategies followed by cultural and social influences, and direct government support (through initiatives and programs for example) are identified as the strongest drivers of entrepreneurship (

Figure 18). Economic policies and national strategies, in particular, stand out as the most influential motivators, highlighting the pivotal role of governmental reforms in fostering a supportive environment for female entrepreneurship. Cultural and social factors also play a significant role, especially as shifting societal norms increasingly support women’s participation in business.

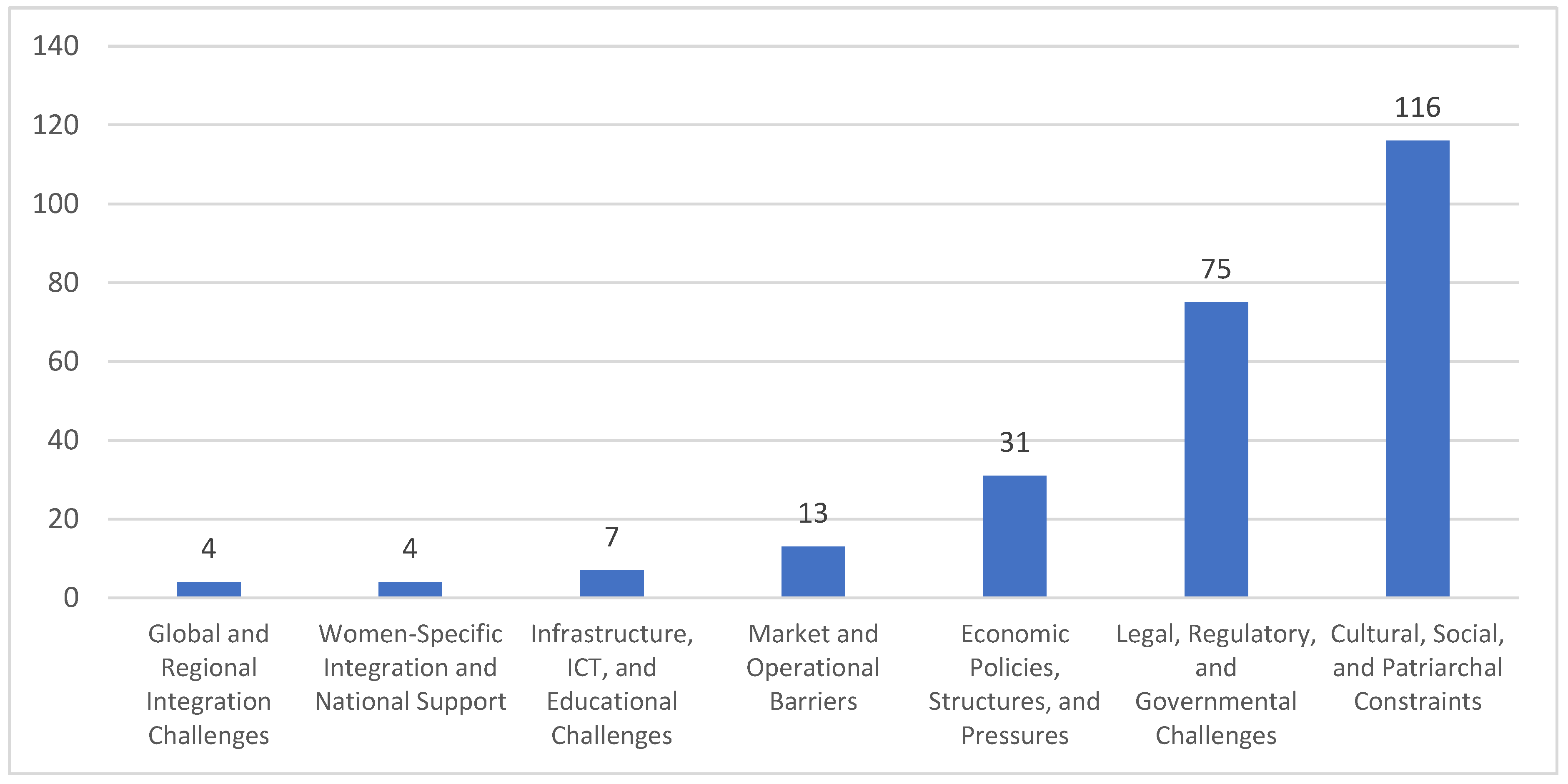

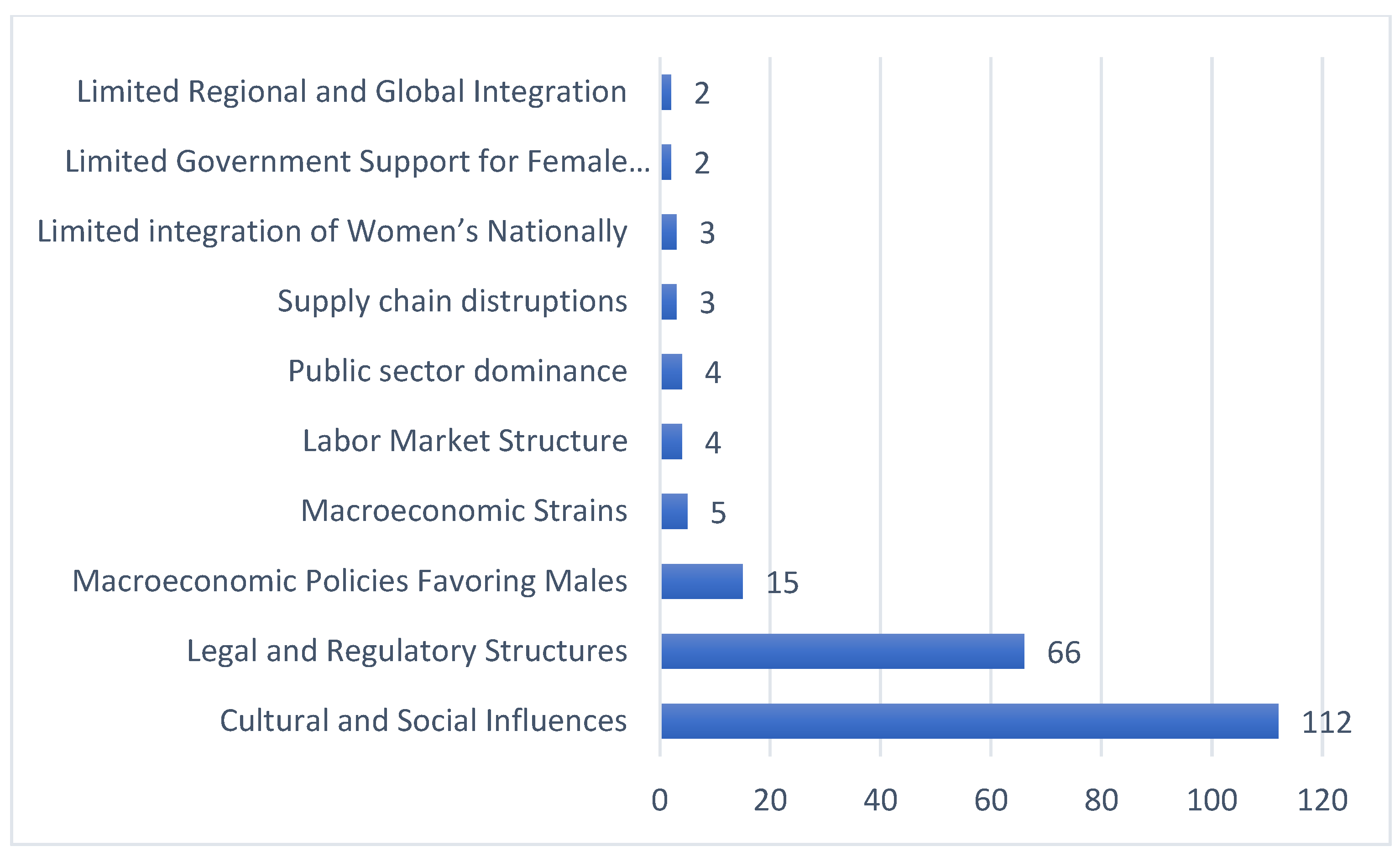

However, these macro-level motivators are counterbalanced by persistent barriers. Key themes in

Figure 19 include cultural, social and patriarchal constraints, followed by legal, regulatory and governmental challenges, and unfavorable economic policies, structures and pressures. Further details are presented in

Figure 20 which reveal that deeply entrenched cultural and social norms, coupled with restrictive legal and regulatory structures, and macroeconomic policies favoring males continue to hinder women’s access to entrepreneurial opportunities. Social and cultural influences, while evolving and gradually empowering women, still present significant challenges due to the persistence of deeply ingrained patriarchal norms and structural inequities that hinder progress. These barriers underscore the need for a broader shift in societal attitudes and the implementation of comprehensive policy reforms to address systemic inequalities and advance gender equality.

9. Discussion

The primary objective of this study is to determine the motivating and inhibiting factors affecting female entrepreneurship as a leverage to sustainability and economic development in the context of the GCC. Female entrepreneurship has become a cornerstone of economic and social progress in GCC countries. Hence, understanding the factors affecting this phenomenon is critical for the sustainability of these countries. The synthesis of motivations and challenges across multi-levels of analysis and taking into consideration the different institutional dimensions offers a comprehensive framework for understanding female entrepreneurship in the GCC. By integrating micro-, meso-, and macro-perspectives, this analysis captures the interconnected nature of individual aspirations, institutional support, and societal structures. This holistic approach not only sheds light on the multifaceted barriers faced by female entrepreneurs but also identifies key opportunities for targeted interventions. Addressing these challenges through an integrated, multilevel strategy is crucial for fostering a more inclusive and supportive entrepreneurial ecosystem, ultimately driving sustainable economic development and promoting gender equity across the GCC region.

The observations derived from the findings and subsequent themes presented in the literature review, provide empirical support that enhances the review’s analytical depth and systemic approach. The compiled findings from the systematic literature review act as a synthesis of motivations and challenges for female entrepreneurship in the GCC, categorized across micro-, meso-, and macro-levels and different institutional dimensions and mechanisms. They further highlight the interplay of individual, institutional, and societal factors shaping the entrepreneurial landscape. The integration of the graph-based observations into the review enriches its systematic approach, offering empirical validation for the multilevel framework.

The findings are consistent with existing studies that examine these factors, albeit often in isolation, and provide an empirical foundation that enhances the review’s analytical depth and systemic approach. They align with studies on emerging and developing countries, which find that access to resources, funding, lack of knowledge, human capital, networking opportunities, discrimination, work-life balance [

61,

62,

115], psychological and personal traits and attitudes, social pressures, gender bias, and weak state-led support and policies are among the key obstacles female entrepreneurs face [

115].

The findings of the study hence complement prior research by underscoring the critical influence of individual factors, such as personal attributes and attitudes [

85]; organizational and sectoral factors, including access to capital, mentorship, and networking [

84]; national factors, such as government policies [

7,

84,

86]; and societal factors [

19,

84,

86], all of which collectively shape the entrepreneurial landscape [

115]. This approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of micro-level aspirations, meso-level institutional support, and macro-level reforms, demonstrating how motivations and challenges manifest across these levels simultaneously. The analysis further reveals the dynamic interplay among various institutional dimensions, particularly the interconnection between regulative and normative pressures at the meso and macro levels.

As noted by DiMaggio and Powell [

42], coercive isomorphism, or the regulative dimension, is driven by two forces: pressures from other organizations (meso level) and the pressure to conform to the cultural expectations of the broader society (macro level). In the context of entrepreneurship, the regulative dimension at the meso level encompasses sector-specific or localized legal frameworks, such as industry standards, organizational codes of conduct, and regionally enforced regulations. At the macro level, it includes overarching legal frameworks at the national or international scale, such as labor laws, trade regulations, and constitutional principles. This aligns with DiMaggio and Powell’s [

42], observation that while each dimension or pillar involves a distinct process, two or more can operate simultaneously, and their effects may not always be clearly distinguishable.

Addressing these multilevel challenges is crucial for enhancing women’s entrepreneurship in the GCC and facilitating sustainable economic development. Strategies such as improving access to education, including entrepreneurial education, creating supportive networks, introducing initiatives focused on entrepreneurial financing, reforming legal frameworks, and fostering a culture that encourages female entrepreneurship, can significantly impact women’s ability to contribute to economic growth in the region. While there have been improvements in women’s participation in entrepreneurship in the GCC in general and notably in Qatar, some challenges continue to pose significant barriers that need to be addressed to foster a more supportive environment for women entrepreneurs [

19,

38,

113].

Micro-level factors influencing women’s entrepreneurship and sustainable economic development in the GCC include personal attributes and cognitive frameworks. Challenges such as fear of failure, psychological barriers, and the dual burden of managing family and business responsibilities significantly hinder entrepreneurial participation. According to Abdelwahed and Alshaikhmubarak [

85], fear of failure and lack of confidence are prominent barriers for women entrepreneurs in Qatar, while Costa and Pita [

116] highlight that Qatari women are less likely than men to pursue entrepreneurship under similar conditions, with age acting as a deterrent factor for women. Despite these challenges, many women are intrinsically motivated by a desire for economic independence, self-fulfillment, and societal contribution, reflecting resilience and adaptability.

Meso-level factors, including institutional frameworks, industry standards, entrepreneurial education programs, and regulatory environments, play a critical role in shaping female entrepreneurship and sustainable economic development in the GCC. As noted by Mulla et al. [

84], systemic barriers such as limited access to funding, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and restricted professional networks and mentorship hinder women’s entrepreneurial success, while Alsaad et al. [

86] underline the crucial role of adequate training and education. Although institutional support structures like education, mentorship, networking opportunities, and role models provide potential enablers, gaps in access to resources, tailored training and education, and inclusive mentorship programs remain significant challenges. Networking limitations, often arising from a preference for private or closed circles, further restrict exposure to broader opportunities essential for business growth. Additionally, while education in the GCC has grown, the limited availability of entrepreneurial education further restricts opportunities, highlighting the need for improvements in this area as well.

At the macro level, women’s entrepreneurship in the GCC is shaped by societal norms, cultural values, legal frameworks, and national policies, in line with Al-Qahtani et al. [

19]. Although rising female education levels, shifting societal attitudes, and initiatives like Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 present new opportunities for women to engage in entrepreneurship, these efforts are often hindered by deeply entrenched cultural biases and insufficient government support. Women entrepreneurs frequently view governmental initiatives as symbolic rather than transformative, contributing to skepticism about their effectiveness.

Therefore, to advance women’s entrepreneurship in the GCC, targeted interventions are needed to address barriers at different levels simultaneously. Key steps to address the limited education and skills, socio-cultural expectations, and work-life balance challenges include building confidence, expanding educational opportunities, and enhancing family support systems, enabling women to scale their businesses, achieve financial stability, and contribute to economic diversification and sustainability [

63]. Meanwhile, gender-sensitive reforms in entrepreneurial ecosystems are critical. These include improving access to financial resources, fostering inclusive training and networking opportunities, and promoting representation through role models and media. Addressing organizational barriers can empower women to contribute more effectively to sustainable development goals in the region. At the macro level, holistic reforms—such as gender-sensitive policies, legal adjustments, and shifts in societal attitudes—are essential to creating an inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem. Studies, such as Abdulwahed [

73] and Ben Hassen [

117], highlight the role of government support and knowledge-based economies in overcoming cultural and institutional barriers, positioning women’s entrepreneurship as a driver of economic diversification and long-term sustainability in the GCC.

10. Policy Recommendations to Encourage Female Entrepreneurship in the GCC: A Comprehensive and Holistic Approach

Female entrepreneurship is shaped by socioeconomic factors, cultural norms, and institutional frameworks, underscoring the need for tailored policies and interventions to support women’s economic endeavors [

118]. Advancing women’s entrepreneurship in the GCC requires a multi-faceted approach to tackle barriers at the individual, organizational, and societal levels. Policymakers must address the interconnected factors influencing female entrepreneurs to foster a more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem that fully leverages women’s potential as drivers of economic growth and sustainability. The policy recommendations, which correspond to each level while accounting for the diverse institutional dimensions and pressures, are summarized in the following table (

Table 3). The recommendations were directly derived from the analysis and results of the SLR and were organized according to the conceptual framework, aiming to address each level of analysis.

11. Conclusions

To achieve economic growth and sustainability through female entrepreneurship, a multi-level policy approach that leverages existing potentials and addresses institutional and systemic barriers is essential. Interventions at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels must be aligned to empower women entrepreneurs, ensure equitable access to resources, and foster inclusive practices. These efforts will enhance women’s ability to drive economic diversification and innovation, contributing to a more competitive and resilient economy in the GCC.

Given the intricate and interdisciplinary nature of female entrepreneurship and its connection to sustainability, a comprehensive approach involving multiple stakeholders is indispensable. Policymakers, support organizations, and women entrepreneurs need to collaborate in order to drive meaningful change by prioritizing capacity-building initiatives in areas such as business management, financial literacy, and technological proficiency. Meanwhile, tailored financial products, such as low-interest loans and green investment funds, should be developed to ensure access to credit and resources. Furthermore, governments are encouraged to enact gender-responsive policies, remove legal barriers, and offer incentives for women-led businesses, particularly in sustainability-oriented industries such as renewable energy and eco-friendly sectors. Digital inclusion, through improved access to e-commerce platforms and digital tools, can further expand market reach and operational efficiency.

Collaborative efforts, taking into consideration various levels of analysis and multiple influencing factors, including public-private partnerships and women’s organizations, are crucial to creating an enabling ecosystem and amplifying women’s voices in policymaking. By adopting these measures, GCC countries can unlock the potential of women entrepreneurs, advancing gender equity, economic diversification, and sustainability goals thereby positioning the region as a progressive and inclusive economic hub.

This study is notably limited to peer-reviewed articles. Future research could broaden its scope by including grey literature, such as reports, theses, conference papers, policy documents, working papers, government publications, and other non-peer-reviewed materials, to capture a wider range of perspectives. Additionally, future studies could expand the geographic focus beyond the GCC to encompass other MENA countries, examining the impact of female entrepreneurship across the three pillars of sustainability: economic, social, and environmental.