Bearing the Burden: Understanding the Multifaceted Impact of Energy Poverty on Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Research on Energy Poverty and Its Intersection with Gender

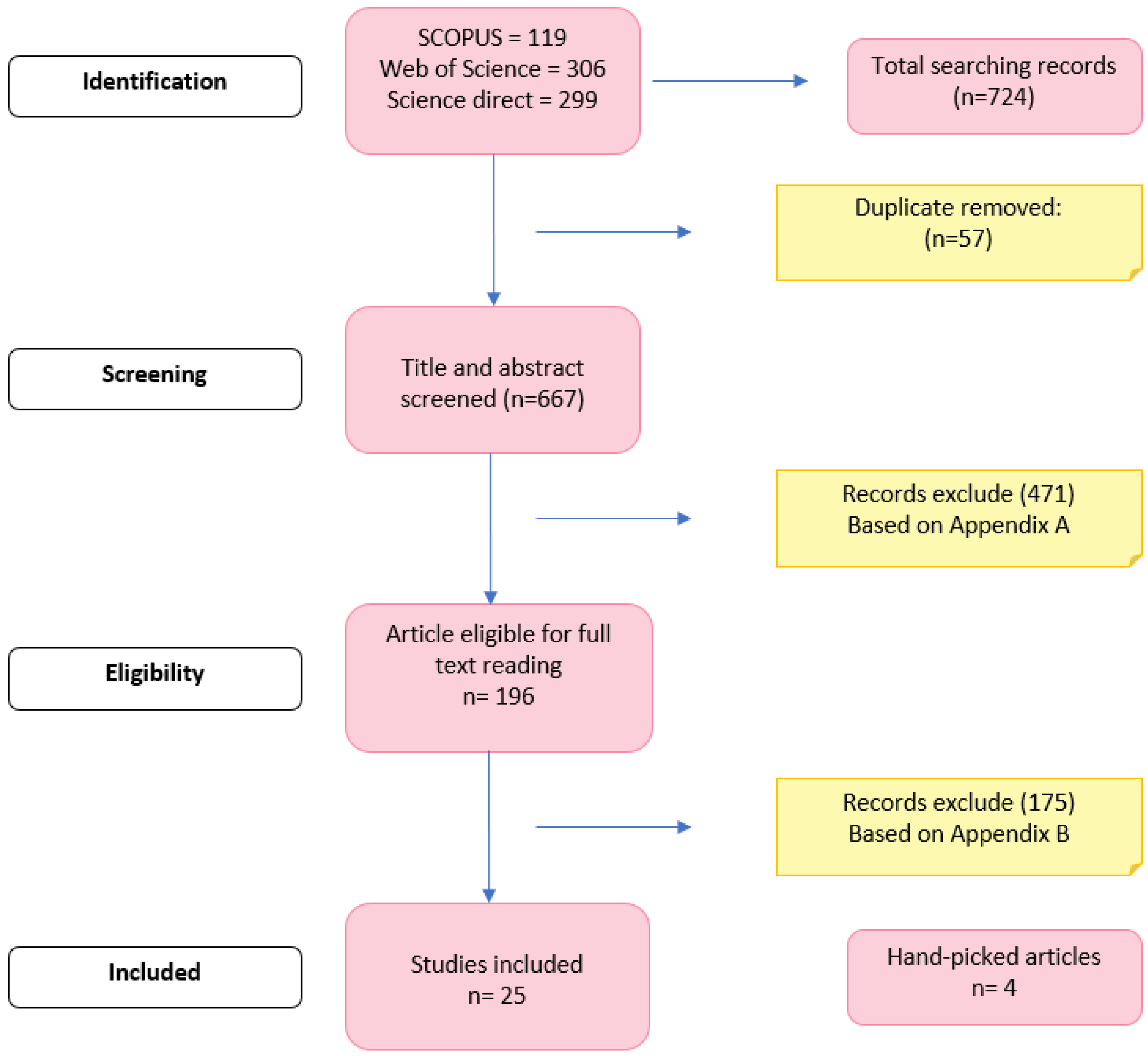

2. Methodology

2.1. Database Selection and Searching Literature

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Selection Process and Extraction

2.4. Analysis and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Description of Authorship, Context, and Content

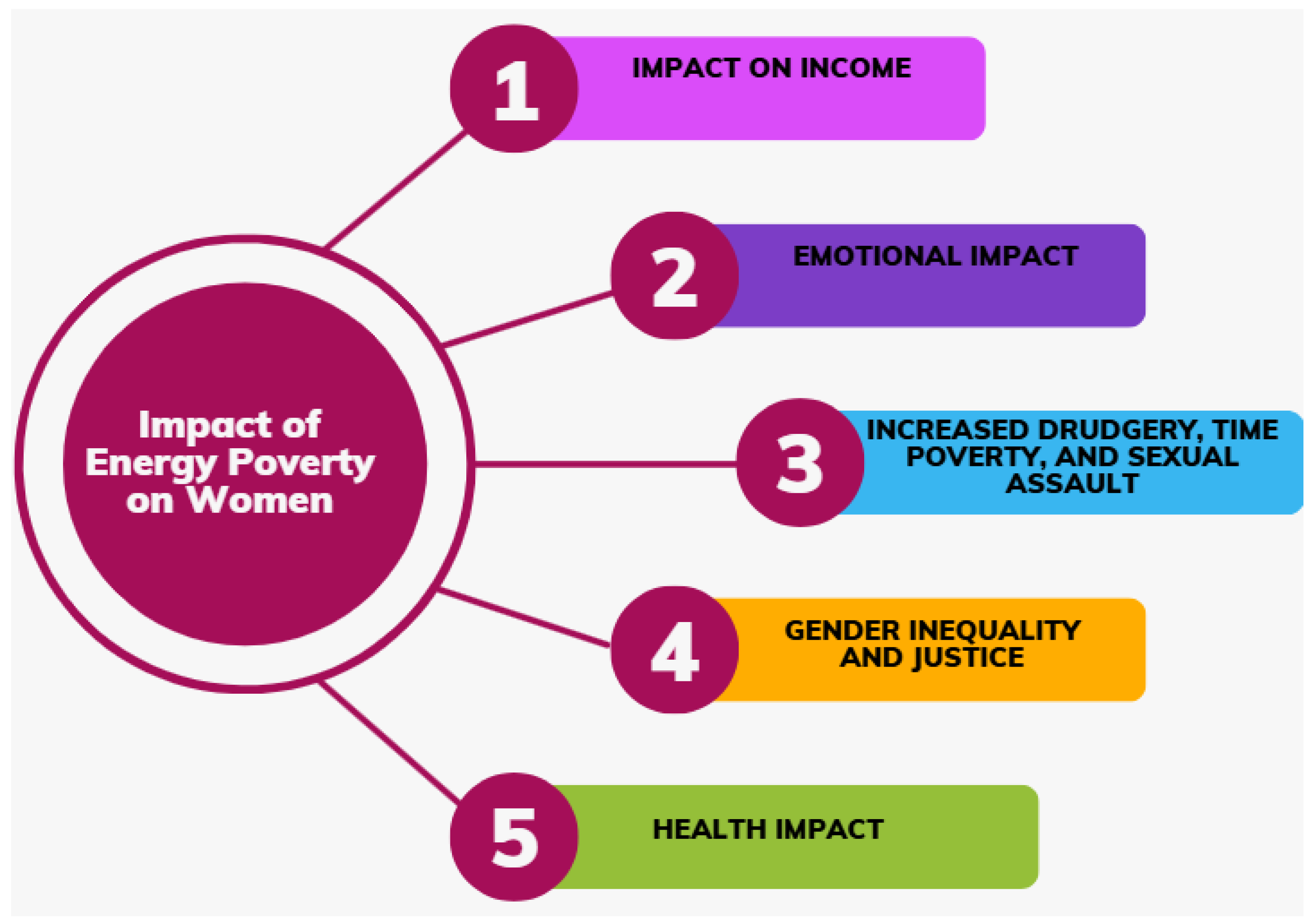

3.2. Themes on Impact of Energy Poverty on Women

3.2.1. Health Impact

3.2.2. Emotional Impact

3.2.3. Impact on Income

3.2.4. Increased Drudgery, Time Poverty, and Sexual Assault

3.2.5. Gender Inequality and Justice

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study Area of Papers | Scopus | Science Direct | Web of Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change | 1 | 27 | 15 |

| Diet, health, and nutrition | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Medical | 9 | 13 | 15 |

| Forest resource | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Language | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Entrepreneurship | 0 | 6 | 16 |

| Solar energy | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| CO2 emission | 0 | 11 | 3 |

| Agriculture and farming | 0 | 24 | 9 |

| Electricity consumption | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| Cooking fuel adoption | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Disability and freedom to movement | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Marketization and finance | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Other papers that are irrelevant to energy poverty | 3 | 131 | 20 |

| 37 | 259 | 175 |

Appendix B

| Focus of the Study | Number of Excluded Articles |

|---|---|

| Children and EP | 3 |

| Culture/race/remittance and EP | 5 |

| Calculation/determinant of EP | 3 |

| Time poverty/Fuel stacking | 5 |

| Single parent/elderly people and fuel poverty | 2 |

| Energy access/energy transition | 14 |

| Income/development and EP | 6 |

| Women politician and EP | 1 |

| Mitigating EP | 1 |

| Crime and EP | 1 |

| Clean cooking fuel | 5 |

| Diet, health and nutrition | 28 |

| Other papers not based on impact of EP on women | 101 |

| Total | 180 |

Appendix C

| Journal name |

| Publication year |

| Authors |

| Title |

| Authors gender |

| Coverage of the study |

| Methodology |

| The central theme of the article |

Appendix D

| SN | Journal and Publication Year | Title | Region of Study | Central Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Energies (2021) | An assessment of the EP and gender nexus towards clean energy adoption in Rural South Africa | Africa | EP and gender |

| 2 | Energy Policy (2022) | Gender and ethnic disparities in EP: The case of South Africa | EP and gender | |

| 3 | SSM-Population Health (2024) | Energy and vulnerability: Exploring the energy poverty-risky sexual behavior nexus among young women in Ghana | EP and risky sexual activities among women | |

| 4 | Energy Research & Social Science (2021) | Women’s work is never done: Lifting the gendered burden of firewood collection and household energy use in Kenya | Energy burden and women | |

| 5 | Applied Research Quality Life (2024) | Multidimensional Energy Poverty in West Africa: Implication for Women’s Subjective Well-being and Cognitive Health | EP and happiness and life satisfaction | |

| 6 | Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy (2021) | Indoor air pollution and gender difference in respiratory health and schooling for children in Cameroon | EP and education | |

| 7 | iScience (2022) | Localized energy burden, concentrated disadvantage, and the feminization of EP | America | Energy burden and women |

| 8 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2022) | EP and depression in Rural China: Evidence from the quantile regression approach | Asia | EP and depression |

| 9 | Social Science & Medicine (2012) | Cooking with biomass increases the risk of depression in pre-menopausal women in India | EP and depression | |

| 10 | Energy Policy (2020) | Gendered EP and energy justice in rural Bangladesh | EP and gender | |

| 11 | Frontiers in Public Health (2022) | Is there gender inequality in the impacts of EP on health? | EP and gender | |

| 12 | Energy and Buildings (2021) | Health implications of household multidimensional EP for women: A structural equation modeling technique | EP and health | |

| 13 | Journal of Asian Economics (2021) | The effects of fuelwood on children’s schooling in rural Vietnam | EP and education | |

| 14 | Energy Economics (2021) | EP and obesity | Australia | EP and obesity |

| 15 | Geoforum (2019) | EP and gender in England: A spatial perspective | Europe | EP and gender |

| 16 | Energy for Sustainable Development (2022) | Mainstreaming a gender perspective into the study of EP in the city of Madrid | EP and gender | |

| 17 | Social &Cultural Geography (2019) | Gender and energy: Domestic inequities reconsidered | EP and gender | |

| 18 | SSM—Population Health (2020) | The association of EP with health, health care utilisation and medication use in Southern Europe | EP and health | |

| 19 | Gaceta Sanitaria (2021) | EP, its intensity and health in vulnerable populations in a Southern European city | EP and health | |

| 20 | International Journal of Health Services (2016) | Housing Policies and Health Inequalities | FP and mental health | |

| 21 | Br. Med. J. (2004) | Vulnerability to winter mortality in elderly people in Britain: Population based study. | FP and mortality | |

| 22 | Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space (2013) | Perceptions of thermal comfort and housing quality: Exploring the micro-geographies of EP in Stakhanov, Ukraine | ||

| 23 | Energy Economics (2021) | EP and public health: Global evidence | Global Studies | EP and health |

| 24 | Energy for Sustainable Development (2021) | Does energy poverty matter for gender inequality? Global evidence | EP and gender inequality | |

| 25 | Technological Forecasting & Social Change (2024) | Energy poverty and gender equality in education: Unpacking the transmission channels | EP and gender inequality |

References

- Cleveland, C.J.; Morris, C. Handbook of Energy, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, M.; Yoon, S.M. Measuring Energy Poverty and Its Impact on Economic Growth in Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan Shrestha, R.; Jirakiattikul, S.; Shrestha, M. “Electricity Is Result of My Good Deeds”: An Analysis of the Benefit of Rural Electrification from the Women’s Perspective in Rural Nepal. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 105, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xie, E. Measuring and Analyzing the Welfare Effects of Energy Poverty in Rural China Based on a Multi-Dimensional Energy Poverty Index. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweke, A.T.; Navrud, S. Valuing Energy Poverty Costs: Household Welfare Loss from Electricity Blackouts in Developing Countries. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoumin, H.; Kimura, F. Cambodia’s Energy Poverty and Its Effects on Social Wellbeing: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, J. Will the Use of Solid Fuels Reduce the Life Satisfaction of Rural Residents—Evidence from China. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 68, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.; Pachauri, S.; Nagai, Y. Analyzing Cooking Fuel and Stove Choices in China till 2030. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2012, 4, 031805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.; Fonseca, P.; Cunha, I.; Morais, N. Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey. Energies 2024, 17, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Nasir, M.A. An Inquiry into the Nexus between Energy Poverty and Income Inequality in the Light of Global Evidence. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan Shrestha, R.; Jirakiattikul, S.; Lohani, S.P.; Shrestha, M. Perceived Impact of Electricity on Productive End Use and Its Reality: Transition from Electricity to Income for Rural Nepalese Women. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueyo, A.; Maestre, M. Linking Energy Access, Gender and Poverty: A Review of the Literature on Productive Uses of Energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winther, T.; Matinga, M.N.; Ulsrud, K.; Standal, K. Women’s Empowerment through Electricity Access: Scoping Study and Proposal for a Framework of Analysis. J. Dev. Eff. 2017, 9, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choragudi, S. Do All the Empowered Women Promote Smokeless Kitchens? Investigating Rural India. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 140903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan Shrestha, R.; Jirakiattikul, S.; Chapagain, B.; Katuwal, H.; Gyawali, S.; Shrestha, M. Biogas Adoption and Its Impact on Women and the Community: Evidence from Nepal. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 81, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Tiwari, S.R.; Bajracharya, S.B.; Keitsch, M.M.; Rijal, H.B. Review on the Importance of Gender Perspective in Household Energy-Saving Behavior and Energy Transition for Sustainability. Energies 2021, 14, 7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.S.; Skutsch, M.; Batchelor, S. The Gender-Energy-Poverty Nexus: Finding the Energy to Address Gender Concerns in Development; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Osunmuyiwa, O.; Ahlborg, H. Inclusiveness by Design? Reviewing Sustainable Electricity Access and Entrepreneurship from a Gender Perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Feng, J.; Luke, N.; Kuo, C.P.; Fu, J.S. Localized Energy Burden, Concentrated Disadvantage, and the Feminization of Energy Poverty. iScience 2022, 25, 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, S.; Simcock, N. Gender and Energy: Domestic Inequities Reconsidered. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Delina, L.L. Energy Poverty and beyond: The State, Contexts, and Trajectories of Energy Poverty Studies in Asia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstündağlı Erten, E.; Güzeloğlu, E.B.; Ifaei, P.; Khalilpour, K.; Ifaei, P.; Yoo, C.K. Decoding Intersectionality: A Systematic Review of Gender and Energy Dynamics under the Structural and Situational Effects of Contexts. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 110, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Norbäck, D. A Systematic Review of Associations between Energy Use, Fuel Poverty, Energy Efficiency Improvements and Wealth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siksnelyte-butkiene, I.; Streimikiene, D.; Lekavicius, V.; Balezentis, T. Energy Poverty Indicators: A Systematic Literature Review and Comprehensive Analysis of Integrity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, N.; Jenkins, K.E.H.; Lacey-Barnacle, M.; Martiskainen, M.; Mattioli, G.; Hopkins, D. Identifying Double Energy Vulnerability: A Systematic and Narrative Review of Groups at-Risk of Energy and Transport Poverty in the Global North. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Arjona, V.; Oliveras, L.; Munoz, J.G.; Olry, A.; Carrere, J.; Ruiz, E.M.; Peralta, A.; Leon, A.C.; Rodriguez, I.M.; Daponte-Codina, A.; et al. What Are the Effects of Energy Poverty and Interventions to Ameliorate It on People’s Health and Well-Being?: A Scoping Review with an Equity Lens. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 87, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munien, S.; Ahmed, F. A Gendered Perspective on Energy Poverty and Livelihoods–Advancing the Millennium Development Goals in Developing Countries. Agenda 2012, 26, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, S.; Rao, N.D. Gender Impacts and Determinants of Energy Poverty: Are We Asking the Right Questions? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listo, R. Gender Myths in Energy Poverty Literature: A Critical Discourse Analysis. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 38, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, M.G.; Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez, C.; Núñez Peiró, M.; Sanz Fernández, A.; López-Bueno, J.A.; Muñoz Gómez, G. Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective into the Study of Energy Poverty in the City of Madrid. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 70, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.S.; Feenstra, M. Women, Gender Equality and the Energy Transition in the EU; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fathallah, J.; Pyakurel, P. Addressing Gender in Energy Studies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R. Energy Poverty and Health: Panel Data Evidence from Australia. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, B.; Acharjee, S.; Mahmud, S.M.A.; Akter, J.; Ali, M.; Islam, S.; Khan, N. Household Air Pollution from Cooking Fuels and Its Association with Under-Five Mortality in Bangladesh. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 17, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Vera-Toscano, E. Energy Poverty and Its Relationship with Health: Empirical Evidence on the Dynamics of Energy Poverty and Poor Health in Australia. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurmi, O.P.; Arya, P.H.; Lam, K.H.; Sorahan, T.; Ayres, J.G. Lung Cancer Risk and Solid Fuel Smoke Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Han, J.; Jang, M.; Suh, M.W.; Lee, J.H. Association between Meniere s Disease and Air Pollution in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Hutton, S. Social Policy Option and Fuel Poverty. J. Econ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Energy Access Outlook 2017: From Poverty to Prosperity. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-access-outlook-2017 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Li, K.; Lloyd, B.; Liang, X.; Wei, Y. Energy Poor or Fuel Poor: What Are the Differences? Energy Policy 2014, 68, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurat-ul-Ann, A.-R.; Mirza, F.M. Meta-Analysis of Empirical Evidence on Energy Poverty: The Case of Developing Economies. Energy Policy 2020, 141, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R. Access to Energy in Mid/Far West Region-Nepal from the Perspective of Energy Poverty. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2299–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, S.; Spreng, D. Energy in and Use Relation Access Energy to Poverty. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2004, 39, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Cooper, C.; Bazilian, M.; Johnson, K.; Zoppo, D.; Clarke, S.; Eidsness, J.; Crafton, M.; Velumail, T.; Raza, H.A. What Moves and Works: Broadening the Consideration of Energy Poverty. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-eguino, M. Energy Poverty: An Overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyanyi, M.E.; Mintah, K.; Baako, K.T. Energy-Related Deprivation and Housing Tenure Transitions. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Novoa, A.M.; Camprubí, L.; Peralta, A.; Vásquez-Vera, H.; Bosch, J.; Amat, J.; Díaz, F.; Palència, L.; Mehdipanah, R.; et al. Housing Policies and Health Inequalities. Int. J. Health Serv. 2016, 47, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadath, A.C.; Acharya, R.H. Assessing the Extent and Intensity of Energy Poverty Using Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index: Empirical Evidence from Households in India. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveras, L.; Peralta, A.; Palencia, L.; Gotsens, M.; Lopez, M.J.; Artazcoz, L.; Borrell, C.; Olmo, M.M. Energy Poverty and Health: Trends in the European Union before and during the Economic Crisis, 2007–2016. Health Place 2021, 67, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, R.; Snell, C.; Bevan, M. Advancing an Energy Justice Perspective of Fuel Poverty: Household Vulnerability and Domestic Retro Fit Policy in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 29, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. Energy Poverty in the European Union: Landscapes of Vulnerability. WIREs Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesala, M.E.; Shambira, N.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P. Exploring Energy Poverty among Off-Grid Households in the Upper Blinkwater Community, South Africa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, I.K.; Yusuf, A.M.; Salihu, M.-K. Impact of Energy Poverty on Education Inequality and Infant Mortality in Some Selected African Countries. Energy Nexus 2022, 5, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.K.; Singha, B.; Karmaker, S.C.; Bari, W.; Chapman, A.J.; Khan, A.; Saha, B.B. Evaluating the Relationship between Energy Poverty and Child Disability: A Multilevel Analysis Based on Low and Middle-Income Countries. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 77, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Appau, S.; Lord, P. Energy Poverty, Children’s Wellbeing and the Mediating Role of Academic Performance: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Han, P. A Multidimensional Measure of Energy Poverty in China and Its Impacts on Health: An Empirical Study Based on the China Family Panel Studies. Energy Policy 2019, 131, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á. Examining Energy Poverty among Vulnerable Women-Led Households in Urban Housing before and after COVID-19 Lockdown: A Case Study from a Neighbourhood in Madrid, Spain. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C.; Bouzarovski, S. Health, Well-Being and Energy Poverty in Europe: A Comparative Study of 32 European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveras, L.; Artazcoz, L.; Borrell, C.; Palència, L.; López, M.J.; Gotsens, M.; Peralta, A.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M. The Association of Energy Poverty with Health, Health Care Utilisation and Medication Use in Southern Europe. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 12, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bîrsănuc, E. Correction to: Mapping Gendered Vulnerability to Energy Poverty in Romania. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 400006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Sánchez-guevara, C.; Fernández, A.S.; Peiró, M.N. Feminisation of Energy Poverty in the City of Madrid. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabha, R.; Ghosh, S.; Padhy, P.K. Effects of Biomass Burning on Pulmonary Functions in Tribal Women in Northeastern India. Women Health 2019, 59, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alim, M.A.; Sarker, M.A.B.; Selim, S.; Karim, M.R.; Yoshida, Y.; Hamajima, N. Respiratory Involvements among Women Exposed to the Smoke of Traditional Biomass Fuel and Gas Fuel in a District of Bangladesh. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, O.; Ana, G.R.; Arinola, G.O.; Wiskel, T.; Falusi, A.G.; Huo, D.; Olopade, O.I.; Olopade, C.O. Effect of Stove Intervention on Household Air Pollution and the Respiratory Health of Women and Children in Rural. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2013, 6, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lin, Z.; Chen, R.; Norback, D.; Liu, C.; Kan, H.; Deng, Q.; Huang, C.; Hu, Y.; Zou, Z.; et al. The Effects of PM2.5 on Asthmatic and Allergic Diseases or Symptoms in Preschool Children of Six Chinese Cities, Based on China, Children, Homes and Health (CCHH) Project. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.G.O.; Machado, C.D.S.; Pinheiro, G.P.; Telles De Oliva, S.; Cristina, R.; Mota, R.C.L.; Lima, V.B.D.e.; Cruz, C.S.; Chatkin, J.M.; Cruz, Á.A. Dual Exposure to Smoking and Household Air Pollution Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Severe Asthma in Adults in Brazil. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2018, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W. A Tale of Two Databases: The Use of Web of Science and Scopus in Academic Papers. Scientometrics 2020, 123, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-Analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaque, A.; Masrur, A.; Rabby, Y.W.; Jerin, T.; Dewan, A. Remote Sensing-Based Research for Monitoring Progress towards SDG 15 in Bangladesh: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, J. Energy Poverty and Depression in Rural China: Evidence from the Quantile Regression Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Siddique, S.; Dutta, A.; Mukherjee, B.; Ray, M.R. Cooking with Biomass Increases the Risk of Depression in Pre-Menopausal Women in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longe, O.M. An Assessment of the Energy Poverty and Gender Nexus towards Clean Energy Adoption in Rural South Africa. Energies 2021, 14, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. Energy Poverty and Gender in England: A Spatial Perspective. Geoforum 2019, 104, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Day, R. Gendered Energy Poverty and Energy Justice in Rural Bangladesh. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngarava, S.; Zhou, L.; Ningi, T.; Chari, M.M.; Mdiya, L. Gender and Ethnic Disparities in Energy Poverty: The Case of South Africa. Energy Policy 2022, 161, 112755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Linghu, Y.; Meng, X.; Yi, H. Is There Gender Inequality in the Impacts of Energy Poverty on Health? Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 986548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrere, J.; Peralta, A.; Oliveras, L.; López, M.J.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Benach, J.; Novoa, A.M. Energy Poverty, Its Intensity and Health in Vulnerable Populations in a Southern European City. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Biru, A.; Lettu, S. Energy Poverty and Public Health: Global Evidence. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Baz, K. Health Implications of Household Multidimensional Energy Poverty for Women: A Structural Equation Modeling Technique. Energy Build. 2021, 234, 110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.; Munyanyi, M.E. Energy Poverty and Obesity. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, M.A.; Chirstian, A.K.; Essel-gaisey, F. Energy and Vulnerability: Exploring the Energy Poverty-Risky Sexual Behavior Nexus among Young Women in Ghana. SSM Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.; Pattenden, S.; Armstrong, B.; Fletcher, A.; Kovats, R.S.; Mangtani, P.; McMichael, A.J. Vulnerability to Winter Mortality in Elderly People in Britain: Population Based Study. Br. Med. J. 2004, 329, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, M.; Gitau, J.K.; Mendum, R. Women’s Work Is Never Done: Lifting the Gendered Burden of Firewood Collection and Household Energy Use in Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, S.; Gentile, M.; Bouzarovski, S.; Mäkinen, I.H. Perceptions of Thermal Comfort and Housing Quality: Exploring the Microgeographies of Energy Poverty in Stakhanov, Ukraine. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 1240–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Su, T.D. Does Energy Poverty Matter for Gender Inequality? Global Evidence. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 64, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Opoku, E.E.O.; Amankwaa, A.; Dzator, J. Energy Poverty and Gender Equality in Education: Unpacking the Transmission Channels. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 202, 123274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsenkyire, E.; Nunoo, J.; Sebu, J.; Nkrumah, R.K.; Amankwano, P. Multidimensional Energy Poverty in West Africa: Implication for Women’s Subjective Well-Being and Cognitive Health. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024, 19, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakehe, N.P. Indoor Air Pollution and Gender Difference in Respiratory Health and Schooling for Children in Cameroon. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2024, 82, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Do, P.; Edelson, M. The Effects of Fuelwood on Children’s Schooling in Rural Vietnam. J. Asian Econ. 2021, 72, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot Review Team. The Health Impacts of Cold Homes and Fuel Poverty; Institute of Health Equity: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O. Thousands of People in the UK Are Dying from the Cold, and Fuel Poverty Is to Blame; The Guardian, 27 February 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/27/dying-cold-europe-fuel-poverty-energy-spending (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Grey, C.N.B.; Schmieder-gaite, T.; Jiang, S.; Nascimento, C.; Poortinga, W. Cold Homes, Fuel Poverty and Energy Efficiency Improvements: A Longitudinal Focus Group Approach. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, A.; Baker, E. Cold Homes and Mental Health Harm: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 314, 115461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, D.J.; Reames, T.G. Recognition of and Response to Energy Poverty in the United States. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguillo, M.; Barisone, M.; Juez-martel, P. Which Cooking and Heating Fuels Are More Likely to Be Used in Energy-Poor Households? Exploring Energy and Fuel Poverty in Argentina. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 87, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guertler, P.; Smith, P. Cold Homes and Excess Winter Deaths; E3G: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teller-Elsberg, J.; Sovacool, B.; Smith, T.; Laine, E. Fuel Poverty, Excess Winter Deaths, and Energy Costs in Vermont: Burdensome for Whom? Energy Policy 2016, 90, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska, L.; Śmiech, S. Invisible Energy Poverty? Analysing Housing Costs in Central and Eastern Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, U.; Meier, H. Energy Affordability and Energy Inequality in Europe: Implications for Policymaking. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 18, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaye, A. Access to Energy and Human Development, Human Development; Report 2007/2008; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Jain, S. Impact of Intervention of Biomass Cookstove Technologies and Kitchen Characteristics on Indoor Air Quality and Human Exposure in Rural Settings of India. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisfeld, K.; Seebauer, S. The Energy Austerity Pitfall: Linking Hidden Energy Poverty with Self-Restriction in Household Use in Austria. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, J.D.; Clinch, J.P. Quantifying the Severity of Fuel Poverty, Its Relationship with Poor Housing and Reasons for Non-Investment in Energy-Saving Measures in Ireland. Energy Policy 2004, 32, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Peiro, M.; Sanchez, C.S.-G.; Sanz-Fernandez, A.; Gayoso-Heredia, M.; Lopez-Bueno, J.; Gonzalez, F.J.N.; Linares, C.; Diaz, J.; Gomez-Munoz, G. Exposure and Vulnerability Toward Summer Energy Poverty in the City of Madrid: A Gender Perspective. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Bisello, A., Vettorato, D., Haarstad, H., Beurden, J.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783030573317. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, S.; Barnes, P.J. Is Exposure to Biomass Smoke the Biggest Risk Factor for COPD Globally. Chest 2010, 138, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, D.; Jindal, S.K. Respiratory Symptoms in Indian Women Using Domestic Cooking Fuels. Chest 1991, 100, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, J.Y.T.; Fitzgerald, J.M.; Carlsten, C. Respiratory Disease Associated with Solid Biomass Fuel Exposure in Rural Women and Children: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2011, 66, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, C.; Chandramohan, D. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Associations between Indoor Air Pollution and Tuberculosis. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2013, 18, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Shrestha, M.K.; Manandhar, A.; Gurung, R.; Sadhra, S.; Cusack, R.; Chaudhary, N.; Ruit, S.; Ayres, J.; Kurmi, O.P. Effect of Exposure to Biomass Smoke from Cooking Fuel Types and Eye Disorders in Women from Hilly and Plain Regions of Nepal. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kc, A.; Halme, S.; Gurung, R.; Basnet, O.; Olsson, E.; Malmqvist, E. Association between Usage of Household Cooking Fuel and Congenital Birth Defects-18 Months Multi-Centric Cohort Study in Nepal. Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chandio, A.A.; Duan, Y.; Zang, D. How Does Clean Energy Consumption Affect Women’s Health: New Insights from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Bandyopadhyay, K.R.; Kumar, A. Exploring the nature of rural energy transition in India Insights from case studies of eight villages in Bihar. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2017, 11, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, C.F.; Schlesinger, S.B.; Molina, E.; Bejarano, M.L.; Valarezo, A.; Jack, D.W. Household fuel mixes in peri-urban and rural Ecuador: Explaining the context of LPG, patterns of continued firewood use, and the challenges of induction cooking. Energy Policy 2020, 136, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sana, A.; Kafando, B.; Dramaix, M.; Meda, N.; Bouland, C. Household energy choice for domestic cooking: Distribution and factors influencing cooking fuel preference in Ouagadougou. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 18902–18910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassie, Y.T.; Rannestad, M.M.; Adaramola, M.S. Determinants of household energy choices in rural sub-Saharan Africa: An example from southern Ethiopia. Energy 2021, 221, 119785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, M.H.; MacCarty, N. What motivates behavior change? Analyzing user intentions to adopt clean technologies in low-resource settings using the theory of planned behavior. Energies 2020, 13, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi, N.V.; Haruna, E.U.; Abdu, N.; Morataya, S.D.A.; Dioha, M.O.; Abraham-Dukuma, M.C. Urban and rural household energy transition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does spatial heterogeneity reveal the direction of the transition? Energy Policy 2022, 168, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, V.; McDade, S.; Lallement, D.; Saghir, J. Energy services for the millennium development goals. 2005. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/MP_Energy2006.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Kaygusuz, K. Energy services and energy poverty for sustainable rural development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjørring, L. We forgot half of the population! The significance of gender in Danish energy renovation projects. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Bessette, D.L. Time-use among men and women in Zambia: A comparison of grid, off-grid, and unconnected households. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M. The justice and equity implication of the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Bruin, A.D.; Welter, F. A gender aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2009, 1, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. Influence of cooking energy for people’s health in rural China: Based on CLDS data in 2014. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, S. Gender differences in thermal comfort and use of thermostats in everyday thermal environments. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X.; You, J.; Lin, Y. Physiology & behavior investigation of gender difference in human response to temperature step changes. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 151, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, A.O.; Mah, D.N.; Barber, L.B. Revealing hidden energy poverty in Hong Kong: A multi-dimensional framework for examining and understanding energy poverty. Local Environ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, C.; Guiney, C. Living in a cold and damp home: Frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being. Public Health 2015, 129, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, J.; Grimsley, M.; Green, G. Psychosocial routes from housing investment to health: Evidence from England’s home energy efficiency scheme. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; Fernández, A.S.; Sánchez, C.S.-G.; Rubio-Bellido, C. Assessment of energy poverty in Andalusian municipalities. Application of a combined indicator to detect priorities. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 5100–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crentsil, O.A.; Asuman, D.; Penny, A.P. Assessing the determinants and drivers of multidimensional energy poverty in Ghana. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winther, T.; Ulsrud, K.; Matinga, M.; Govindan, M.; Gill, B.; Saini, A.; Brahmachari, D.; Palit, D.; Murali, R. In the light of what we cannot see: Exploring the interconnections between gender and electricity access. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 60, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakehe, N.P. Energy poverty: Consequences for respiratory health and labour force participation in Cameroon. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreosatou, Z. Energy Poverty and Gender Nexus—A Case Study Analysis from Greece. 2024. Available online: https://ieecp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/JUSTEM_Report_Energy-Poverty-and-Gender.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Liu, H.; Dong, Y.; Luo, C. Why do women bear more? The impact of energy poverty on son preference in Chinese rural households. Energy Policy 2024, 195, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenido-Huertas, D. Do unemployment benefits and economic aids to pay electricity bills remove the energy poverty risk of Spanish family units during lockdown? A study of COVID-19-induced lockdown. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecelski, E. The Role of Women in Sustainable Economic Development. Colorado. 2000. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy00osti/26889.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Agrawal, B. Cold Hearths and Barren Slopes: The Wood Fuel Crisis in the Third World; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, J. Hardships and health impacts on women due to traditional cooking fuels: A case study of Himachal Pradesh. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7587–7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewald, R. Energy and Women and Girls: Analyzing the Needs, Uses, and Impact of Energy on Women and Girls in the Developing World. Oxfam Research Backgrounder Series. 2017. Available online: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/energy-women-girls/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Gafa, D.W.; Egbendewe, A.Y.G. Energy poverty in rural West Africa and its determinants: Evidence from Senegal and Togo. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainisio, N.; Boffi, M.; Pola, L.; Inghilleri, P.; Sergi, I.; Liberatori, M. The role of gender and self-efficacy in domestic energy saving behaviors: A case study in Lombardy, Italy. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchi, J.I.; Managi, S. Preferences for energy sustainability: Different effects of gender on knowledge and importance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, F.; Fernández-Vázquez, E.; Serrano, M. The Gender–Energy–Poverty Nexus under Review: A Longitudinal Study for Spain. In Vulnerable Households in the Energy Transition. Studies in Energy, Resource and Environmental Economics; Bardazzi, R., Pazienza, M.G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; p. 117. ISBN 9783031356834. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, M.N.; Bharadwaj, B.; Rafiq, S. Who Benefits from the Decentralised Energy System (DES)? Evidence from Nepal’s Micro-Hydropower (MHP). Energy Econ. 2023, 120, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Krishnapriya, P.P.; Jeuland, M.; Pattanayak, S.K. Gender Empowerment and Energy Access: Evidence from Seven Countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Sakutukwa, T.; Yew, S.P.L. The Impact of Energy Poverty on Physical Violence. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-hernández, P.; Mejía-montero, A.; van Der Horst, D. Characterisation of Energy Poverty in Mexico Using Energy Justice and Econophysics. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 71, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Code | Initial Article Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | ((energy poverty) or (fuel poverty) and (impact or effect) and (gender or wom*n)) | 306 |

| Scopus | 119 | |

| Science Direct | 299 | |

| Google Scholar | Impact of energy poverty on women | 4 (Hand-picked) |

| SN | Journal and Publication Year | Authors | Title | First Authors Sex | Coverage of the Study (Methodology) | Central Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2022) | Zhang J. et al. [71] | EP and depression in Rural China: Evidence from the quantile regression approach | Male | China (Quan) | EP and depression |

| 2 | Social Science & Medicine (2012) | Banerjee, M. et al. [72] | Cooking with biomass increases the risk of depression in pre-menopausal women in India | Female | India (Quan) | |

| 3 | Energies (2021) | Longe, O.M. [73] | An assessment of the EP and gender nexus towards clean energy adoption in Rural South Africa | Female | South Africa (Mixed) | EP and gender |

| 4 | Geoforum (2019) | Robinson, C. [74] | EP and gender in England: A spatial perspective | Female | England (Quan) | EP and gender |

| 5 | Energy Policy (2020) | Moniruzzaman, M. and Day, R. [75] | Gendered EP and energy justice in rural Bangladesh | Male | Bangladesh (Qual) | |

| 6 | Energy for Sustainable Development (2022) | Heredia, M.G. et al. [30] | Mainstreaming a gender perspective into the study of EP in the city of Madrid | Female | Spain (Qual) | |

| 7 | Energy Policy (2022) | Ngarava, S. et al. [76] | Gender and ethnic disparities in EP: The case of South Africa | Male | South Africa (Quan) | |

| 8 | Social & Cultural Geography (2019) | Petrova, S. and Simcock, N. [20] | Gender and energy: Domestic inequities reconsidered | Female | Poland, Greece and Czechia (Qual) | |

| 9 | Frontiers in Public Health (2022) | Zhang, Z.Y. et al. [77] | Is there gender inequality in the impacts of EP on health? | Male | China (Quan) | |

| 10 | SSM—Population Health (2020) | Oliveras, L. et al. [59] | The association of EP with health, health care utilisation and medication use in Southern Europe | Female | Spain (Quan) | EP and health |

| 11 | Gaceta Sanitaria (2021) | Carrere, J. et al. [78] | EP, its intensity and health in vulnerable populations in a Southern European city | Female | Spain (Quan) | |

| 12 | Energy Economics (2021) | Pan, L. et al. [79] | EP and public health: Global evidence | Male | 175 countries (Quan) | |

| 13 | Energy and Buildings (2021) | Abbas, K. et al. [80] | Health implications of household multidimensional EP for women: A structural equation modeling technique | Male | South and South East Asia (11 countries) (Quan) | |

| 14 | Energy Economics (2021) | Prakash, K. and Munyanyi, M.E. [81] | EP and obesity | Male | Australia (Quan) | EP and obesity |

| 15 | SSM-Population Health (2024) | Okyere, M. et al. [82] | Energy and vulnerability: Exploring the energy poverty-risky sexual behavior nexus among young women in Ghana | Male | Ghana (Quan) | EP and risky sexual activities among women |

| 16 | International Journal of Health Services (2016) | Marí-Dell’Olmo, M. et al. [47] | Housing Policies and Health Inequalities | Male | Spain (Quan) | FP and mental health |

| 17 | Br. Med. J. (2004) | Wilkinson, P. et al. [83] | Vulnerability to winter mortality in elderly people in Britain: Population based study. | Male | Britain (Quan) | FP and mortality |

| 18 | Energy Research & Social Science (2021) | Njenga, M. et al. [84] | Women’s work is never done: Lifting the gendered burden of firewood collection and household energy use in Kenya | Male | Kenya (Mixed) | Energy burden and women |

| 19 | iScience (2022) | Chen, C. et al. [19] | Localized energy burden, concentrated disadvantage, and the feminization of EP | Female | USA (Quan) | |

| 20 | Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space (2013) | Petrova, S. et al. [85] | Perceptions of thermal comfort and housing quality: Exploring the micro-geographies of EP in Stakhanov, Ukraine | Female | Ukraine (Quan) | EP and housing condition |

| 21 | Energy for Sustainable Development (2021) | Nguyen, C. and Su, T. [86] | Does energy poverty matter for gender inequality? Global evidence | Male | 51 Developing countries (Quan) | EP and gender inequality |

| 22 | Technological Forecasting & Social Change (2024) | Acheampong, A.O. et al. [87] | Energy poverty and gender equality in education: Unpacking the transmission channels | Male | 98 Countries (Quan) | |

| 23 | Applied Research Quality Life (2024) | Nsenkyire, E. et al. [88] | Multidimensional Energy Poverty in West Africa: Implication for Women’s Subjective Well-being and Cognitive Health | Female | Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Ghana (Quan) | EP and happiness and life satisfaction |

| 24 | Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy (2021) | Bakehe, N.P. [89] | Indoor air pollution and gender difference in respiratory health and schooling for children in Cameroon | Male | Cameroon (Quan) | EP and education |

| 25 | Journal of Asian Economics (2021) | O’Brien, J. et al. [90] | The effects of fuelwood on children’s schooling in rural Vietnam | Male | Vietnam (Quan) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pradhan Shrestha, R.; Mainali, B.; Mokhtara, C.; Lohani, S.P. Bearing the Burden: Understanding the Multifaceted Impact of Energy Poverty on Women. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052143

Pradhan Shrestha R, Mainali B, Mokhtara C, Lohani SP. Bearing the Burden: Understanding the Multifaceted Impact of Energy Poverty on Women. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052143

Chicago/Turabian StylePradhan Shrestha, Rosy, Brijesh Mainali, Charafeddine Mokhtara, and Sunil Prasad Lohani. 2025. "Bearing the Burden: Understanding the Multifaceted Impact of Energy Poverty on Women" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052143

APA StylePradhan Shrestha, R., Mainali, B., Mokhtara, C., & Lohani, S. P. (2025). Bearing the Burden: Understanding the Multifaceted Impact of Energy Poverty on Women. Sustainability, 17(5), 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052143