Educational Aspects Affecting Paramedic Preparedness and Sustainability of Crisis Management: Insights from V4 Countries and the Role of Innovative Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Key Variables of the Study

2.3. Sample Size

- The Slovak Republic: 2960 paramedics,

- The Czech Republic: 4350 paramedics,

- Poland: 8259 paramedics,

- Hungary: 7542 paramedics.

- the Slovak Republic (n = 408), survey success rate: 408/2960 = 13.78%, confidence level 95%, and margin of error 5%.

- the Czech Republic (n = 414), survey success rate: 414/4350 = 9.52%, confidence level 95%, and margin of error 5%.

- Poland (n = 440), survey success rate: 440/8259 = 5.33%, confidence level 95%, and margin of error 5%.

- Hungary (n = 417), survey success rate: 417/7542 = 5.53%, confidence level 95%, and margin of error 5%.

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Assessing the Differences Between the Countries Studied

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Years of Experience

Level of Satisfaction with Employer’s Training and Education

Educational Activities

Evaluation of Expertise in Critically Ill Patient Management

3.3. Variables Affecting How Often Paramedics Feel They Lack Knowledge and Skills

3.4. Critical Situations

4. Discussion, Recommendations, and Limitations

4.1. Factors Influencing Perceived Lack of Knowledge

4.2. Recommodations

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brooks, I.A.; Sayre, M.R.; Spencer, C.; Archer, F.L. A Historical Examination of the Development of Emergency Medical Services Education in the U.S. through Key Reports (1966–2014). Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2016, 31, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruna, J.; Uemura, S.; Taguchi, Y.; Muranaka, S.; Niiyama, S.; Inamura, H.; Sawamoto, K.; Mizuno, H.; Narimatsu, E. Influence of Work and Family Environment on Burnout among Emergency Medical Technicians. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 10, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Meara, P.; O’Neill, B.J.; Brightwell, R. Violence Against Emergency Medical Services Personnel: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.D.; Weaver, M.D.; Hostler, D.; Guyette, F.X.; Callaway, C.W.; Yealy, D.M. The Shift Length, Fatigue, and Safety Conundrum in EMS. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2012, 16, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlar, M. Cognitive Skills of Emergency Medical Services Crew Members: A Review of the Literature. BMC Emerg. Med. 2020, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayadelen, C.L.; Kayadelen, A.N.; Durukan, P. Factors Influencing Paramedics’ and Emergency Medical Technicians’ Knowledge about the 2015 Basic Life Support Guidelines. BMC Emerg. Med. 2021, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L.; Devenish, S.; Long, D.; Tippett, V. Facilitators, Barriers, and Motivators of Paramedic Continuing Professional Development. Australas. J. Paramed. 2021, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, R.; MacKenzie, R. Competence in Prehospital Care: Evolving Concepts. Emerg. Med. J. 2005, 22, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, Z. Loneliness—A clinical primer. Br. Med. Bull. 2023, 145, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Vopelius-Feldt, J.; Wood, J.; Benger, J. Critical care paramedics: Where is the evidence? A systematic review. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, M.K.; Cash, R.E.; Mercer, C.B.; Chrzan, K.; Panchal, A.R. Demographics of the National Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Description of Those Providing Patient Care in the Prehospital Setting. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2021, 25, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Meara, P.F.; Brightwell, R.F.; O’Neill, B.J.; Fitzgerald, G.J. Occupational Injury Risk among Australian Paramedics: An Analysis of National Data. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 200, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, J.A.; Francis, A.J.; Paxton, S.J. Caring for the Carers: Fatigue, Sleep and Mental Health in Australian Shiftworking Health Professionals. Australas. J. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 3, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, M.; Abrahams, R.; Thyer, L.; Simpson, P. Review Article: Prevalence of Burnout in Paramedics: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Studies. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2020, 32, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barziej, I.; Hasij, J.; Orłowska, W.; Rydzek, J.; Letka, E. Management of Agitated and Aggressive Patients. Rescue 2010, 2, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Żurowska-Wolak, M.; Wolak, B.; Mikos, M.; Juszczyk, G.; Czerw, A. Stress and Professional Burnout in the Work of Medical Rescuers. J. Educ. Health Sport 2015, 5, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski, A.; Stankiewicz, S. The Phenomenon of Occupational Stress in the Work of a Medical Rescuer. In Ochrona Zdrowia Pracujących; Chmielewski, J., Czarny-Działak, M., Pawlas, N., Eds.; Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Andrštová, A. Psychology and Communication for Paramedics in Practice; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kajermo, K.N.; Nordström, G.; Krusebrant, A.; Björvell, H. Perceptions of Research Utilization: A Comparison between Health Professionals, Nursing Students and a Reference Group of Clinical Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, N.; Krol, M.; Veenvliet, C.; Plass, A.M. Ambulance Care in Europe. 2015. Available online: https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Rapport_ambulance_care_europe.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Brooks, I.A.; Cooke, M.; Spencer, C.; Archer, F. A Review of Key National Reports to Describe the Development of Paramedic Education in England (1966–2014). Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 33, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandifer, S.P.; Wexler, B.J.; Flamm, A. Comparison of Disaster Medicine Education in Emergency Medicine Residency and Emergency Services Fellowship in the United States. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.E.; Leggio, W.J.; Powell, J.R.; McKenna, K.D.; Rosenberger, P.; Carhart, E.; Kramer, A.; March, J.A.; Panchal, A.R. Emergency medical services education research priorities during COVID-19: A modified Delphi study. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians 2021, 2, e12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moungey, B.M.; Mercer, C.B.; Powell, J.R.; Cash, R.E.; Rivard, M.K.; Panchal, A.R. Paramedic and EMT Program Performance on Certification Examinations Varies by Program Size and Geographic Location. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2022, 26, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.N. The formation of the emergency medical services system. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weile, J.; Nebsbjerg, M.A.; Ovesen, S.H.; Paltved, C.; Ingeman, M.L. Simulation-Based Team Training in Time-Critical Clinical Presentations in Emergency Medicine and Critical Care: A Review of the Literature. Adv. Simul. 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, T.R.; Wood, E.A.; McManus, J.; Ma, K.; Wallach, P.M. The impact of an Emergency Medical Technician basic course prior to medical school on medical students. Med. Educ. Online 2018, 23, 1474699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N.E.; Slark, J.; Faasse, K.; Gott, M. Paramedic student confidence, concerns, learning and experience with resuscitation decision-making and patient death: A pilot survey. Australas. Emerg. Care 2019, 22, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operational Centre of the Rescue Health Service of the Slovak Republic. Annual Report 2022/2023; Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovak, 2023; Available online: https://155.sk/subory/dokumenty/vyrocne_spravy/Vyrocna_sprava_OSZZSSR_2023.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- MZ SR. Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic Statistical Data on Emergency Medical Services on the Territory of the Slovak Republic (Report for 2022/2023); MZ SR: Bratislava, Slovak, 2023. Available online: https://www.health.gov.sk/ (accessed on 3 November 2024). (In Slovak)

- Peran, D.; Sykora, R.; Vidunova, J.; Krsova, I.; Pekara, J.; Renza, M.; Brizgalova, N.; Cmorej, P.C. Non-Technical Skills in Pre-Hospital Care in the Czech Republic (NTS Study): A Prospective-Multicenter Observational Study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowny Urzad Statystyczny. Pomoc Doraźna i Ratownictwo Medyczne w 2019 r. 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5513/14/4/1/pomoc_dorazna_i_ratownictwo_medyczne_w_2019_r.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Gonczaryk, A.; Chmielewski, J.P.; Strzelecka, A.; Fiks, J.; Witkowski, G.; Florek-Luszczki, M. Occupational hazards in the consciousness of the paramedic in emergency medical service. Disaster Emerg. Med. J. 2022, 7, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandur, A.; Priskin, G.; Tóth, B.; Furedi, G.; Radnai, B.; Betlehem, J.; Schiszler, B. National Ambulance Service in Hungary—Graduated System for the Prehospital Medicalization. J. Eur. Urg. Réanimation 2022, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Országos Mentőszolgálat. Hungarian Rescue History. Available online: https://www.mentok.hu/en/about-us/ (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Sikka, N.; Margolis, G. Understanding diversity among prehospital care delivery systems around the world. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald, G.J. Paramedics and Scope of Practice. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 203, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van den Bergh, S.L.; Logan, L.T.; Powell, J.R.; Gage, C.B.; Crawford, K.R.; Collard, L.; Miller, M.G.; Panchal, A.R. Paramedic educational programs maintain entry level competency throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, J.P.; Karkowski, T.A.; Szpringer, M.; Florek-Łuszczki, M.; Rutkowski, A. Health education in the professional work of paramedics. Med. Og. Nauk Zdr. 2019, 25, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurňáková, J.; Halama, P.; Pitel, L.; Harenčárová, H.; Adamovová, L. Rozhodovanie Profesionálov: Sebaregulácia, Stres a Osobnosť [Decision-Making of Professionals: Self-Regulation, Stress and Personality], 1st ed.; Ústav experimentálnej psychológie SAV: Bratislava, Slovak, 2013; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, B. Paramedics and their role in end-of-life care: Perceptions and confidence. J. Paramed. Pract. 2017, 9, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, S.C.; Abbott, J.; McClung, C.D.; Colwell, C.B.; Eckstein, M.; Lowenstein, S.R. Paramedic Knowledge, Attitudes, and Training in End-of-Life Care. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2009, 24, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; McGovern, R.; Birch, J.; Newbury-Birch, D. Which extended paramedic skills are making an impact in emergency care and can be related to the UK paramedic system? A systematic review of the literature. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuricová, A.; Kočkár, S.; Hollá, K. Innovative forms of education using virtual and augmented reality: Scenarios and simulations and their possibility of use in the teaching process. In Proceedings of the INTED2024 Proceedings: 18th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 4–6 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fanfarová, A.; Mariš, L. Utilization of simulation and virtual reality tools in education of fire and rescue services. Krízový Manažment 2017, 16, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, G. Addressing the challenges facing the paramedic profession in the United Kingdom. Br. Med. Bull. 2023, 148, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelíšek, A.; Kubás, J.; Hollá, K.; Cidlinová, A. Virtual reality education in high school health studies as a prerequisite for increasing the level of security in municipalities. In Proceedings of the ICERI 2023 Proceedings: 16th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 13–15 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boroš, M.; Sventeková, E.; Cidlinová, A.; Bardy, M.; Batrlová, K. Application of VR technology to the training of paramedics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variable | Independent (Explanatory) Variables |

|---|---|

| y-frequency of feeling a lack of knowledge and skills (understood as a number of situations in which paramedics directly experienced a lack of knowledge and skills in practice) | a-years of experience |

| b-level of satisfaction with employer’s training and education | |

| c-number of practical training activities | |

| d-number of theoretical training activities | |

| e-number of external educational activities | |

| f-level of expertise in primary triage of casualties during Mass casualty incident management response | |

| g-level of expertise in practical handling of life-threatening emergencies | |

| h-level of expertise in mass casualty incident management response |

| Summary Groups | Count | Sum | Average | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the Slovak Republic | 408 | 1748 | 4.284 | 46.194 |

| the Czech Republic | 414 | 1892 | 4.570 | 32.318 |

| Poland | 440 | 6196 | 14.082 | 198.608 |

| Hungary | 417 | 4728 | 11.338 | 227.758 |

| ANOVA | Df | F | p-value | F crit |

| Between groups | 3 | 79.966 | 2.399 × 10−48 | 2.610 |

| Descriptive Statistics | Feeling a Lack of Knowledge and Skills | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No = 0 | Yes = 1 | Total | |||||||||||

| Variables * | SVK (n = 175) | CZE (n = 145) | PLN (n = 97) | HUN (n = 118) | SVK (n = 233) | CZE (n = 269) | PLN (n = 343) | HUN (n = 299) | SVK (n = 408) | CZE (n = 414) | PLN (n = 440) | HUN (n = 417) | |

| a | 0–9 | 125 | 120 | 75 | 35 | 168 | 191 | 202 | 76 | 293 | 311 | 277 | 111 |

| 10–19 | 37 | 18 | 18 | 41 | 51 | 73 | 117 | 119 | 88 | 91 | 135 | 160 | |

| 20–29 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 26 | 9 | 4 | 18 | 71 | 18 | 9 | 22 | 97 | |

| 29–39 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 25 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 37 | |

| >40 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 12 | |

| b | 1 to 9 | 4.65 ± 2.06 | 6 ± 1.27 | 5.95 ± 1.44 | 6.42 ± 2.11 | 3.35 ± 1.80 | 3.35 ± 1.80 | 4.90 ± 1.15 | 6.20 ± 1.58 | 3.91 ± 2.02 | 5.86 ± 1.32 | 5.13 ± 1.29 | 6.26 ± 1.75 |

| c | 0–9 | 119 | 102 | 59 | 30 | 182 | 186 | 163 | 46 | 301 | 288 | 222 | 76 |

| 10–19 | 27 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 34 | 66 | 129 | 71 | 61 | 95 | 159 | 101 | |

| 20–29 | 15 | 12 | 6 | 21 | 9 | 10 | 34 | 92 | 24 | 22 | 40 | 113 | |

| 30–39 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 41 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 57 | |

| >40 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 49 | 11 | 3 | 10 | 70 | |

| d | 0–9 | 92 | 62 | 41 | 34 | 124 | 86 | 66 | 37 | 216 | 148 | 107 | 71 |

| 10–19 | 41 | 52 | 40 | 30 | 77 | 129 | 164 | 60 | 118 | 181 | 204 | 90 | |

| 20–29 | 19 | 24 | 8 | 23 | 16 | 40 | 69 | 80 | 35 | 64 | 77 | 103 | |

| 30–39 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 22 | 51 | 18 | 16 | 26 | 61 | |

| >40 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 21 | 6 | 3 | 22 | 71 | 21 | 5 | 26 | 92 | |

| e | 0–9 | 122 | 125 | 74 | 64 | 167 | 226 | 156 | 65 | 289 | 351 | 230 | 129 |

| 10–19 | 23 | 12 | 11 | 24 | 37 | 33 | 72 | 45 | 60 | 45 | 83 | 69 | |

| 20–29 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 19 | 4 | 61 | 65 | 27 | 6 | 66 | 76 | |

| 30–39 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 26 | 55 | 11 | 3 | 28 | 65 | |

| >40 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 28 | 69 | 21 | 9 | 33 | 78 | |

| f | 1 to 9 | 5.22 ± 1.97 | 5.65 ± 1.33 | 6.28 ± 1.45 | 6.25 ± 1.82 | 4.47 ± 2.01 | 5.10 ± 1.55 | 5.02 ± 1.30 | 5.40 ± 1.46 | 4.80 ± 2.03 | 5.30 ± 1.50 | 5.25 ± 1.40 | 5.64 ± 1.61 |

| g | 1 to 9 | 5.33 ± 2.00 | 5.37 ± 1.56 | 6.27 ± 1.45 | 6,77 ± 1,77 | 4.68 ± 1.90 | 5.22 ± 1.50 | 4.98 ± 1.26 | 5.87 ± 1.51 | 4.97 ± 1.97 | 5.27 ± 1.52 | 5.26 ± 1.41 | 6.12 ± 1.64 |

| h | 1 to 9 | 5.01 ± 2.07 | 5.24 ± 1.71 | 5.97 ± 1.52 | 6.26 ± 1.90 | 3.99 ± 2.00 | 4.75 ± 1.75 | 4.69 ± 1.30 | 5.22 ± 1.64 | 4.43 ± 2.10 | 4.92 ± 1.75 | 4.97 ± 1.45 | 5.51 ± 1.78 |

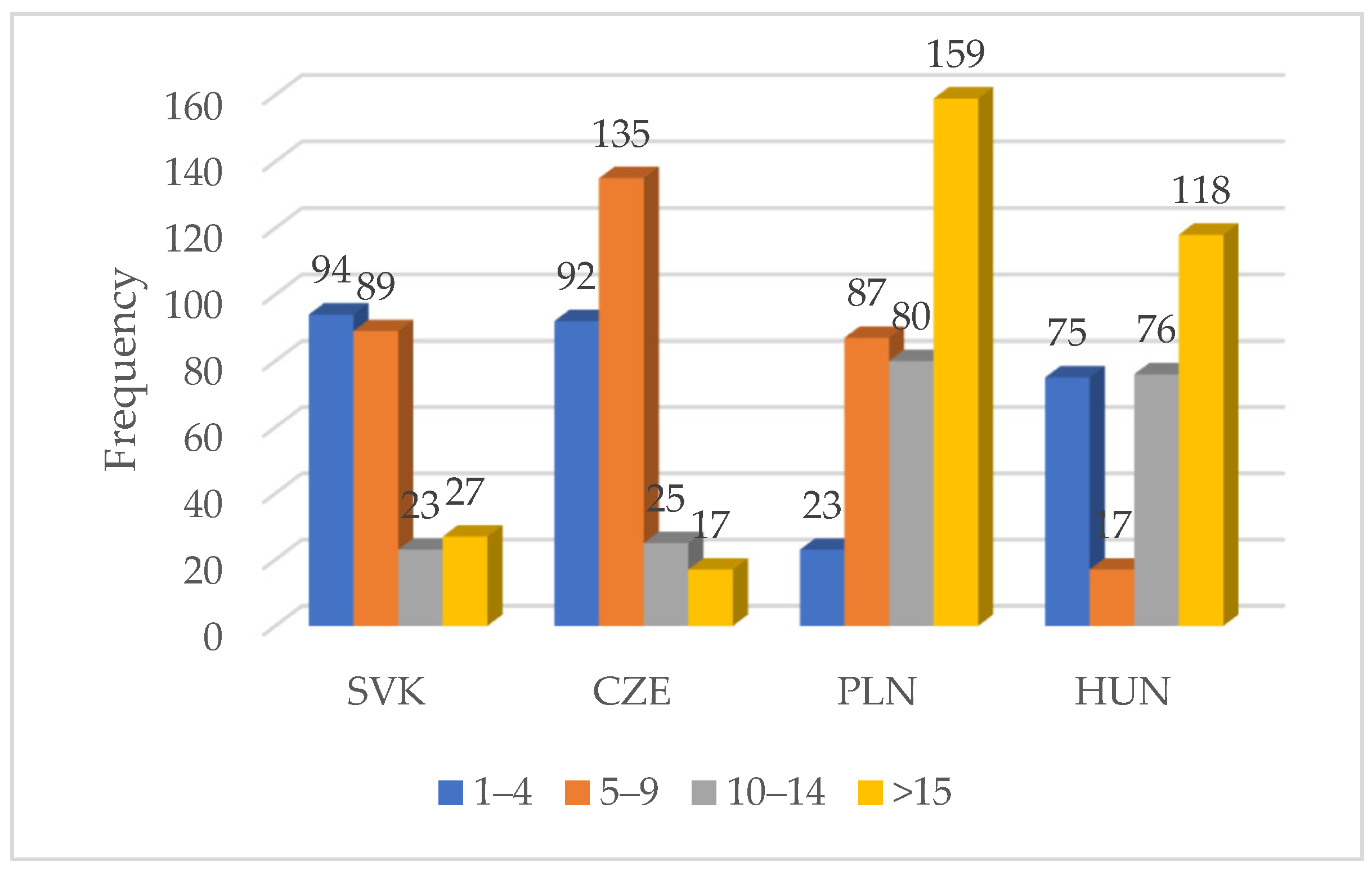

| y | 1–4 | - | - | - | - | 94 | 92 | 23 | 75 | - | - | - | - |

| 5–9 | - | - | - | - | 89 | 135 | 87 | 17 | - | - | - | - | |

| 10–14 | - | - | - | - | 23 | 25 | 80 | 76 | - | - | - | - | |

| >15 | - | - | - | - | 27 | 17 | 159 | 118 | - | - | - | - | |

| The Slovak Republic | Coeff. | p-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| years of experience | 0.152 | 0.0174 | 0.027 | 0.278 |

| level of satisfaction with employer’s training and education | −0.378 | 0.069 | −0.786 | 0.030 |

| number of practical training activities | −0.001 | 0.977 | −0.095 | 0.092 |

| number of theoretical training activities | −0.020 | 0.568 | −0.090 | 0.049 |

| number of external educational activities | 0.065 | 0.0453 | 0.001 | 0.128 |

| level of expertise in primary triage of casualties during mass casualty incident management response | 0.454 | 0.088 | −0.069 | 0.977 |

| level of expertise in practical handling of life-threatening emergencies | 0.107 | 0.629 | −0.327 | 0.541 |

| level of expertise in mass casualty incident management response | −0.787 | 0.0028 | −1.303 | −0.271 |

| The Czech Republic | Coeff. | p-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| years of experience | 0.072 | 0.267 | −0.055 | 0.198 |

| level of satisfaction with employer’s training and education | −0.429 | 0.053 | −0.864 | 0.005 |

| number of practical training activities | 0.078 | 0.223 | −0.048 | 0.204 |

| number of theoretical training activities | 0.056 | 0.232 | −0.036 | 0.147 |

| number of external educational activities | −0.014 | 0.675 | −0.079 | 0.051 |

| level of expertise in primary triage of casualties during mass casualty incident management response | −0.351 | 0.091 | −0.758 | 0.057 |

| level of expertise in practical handling of life-threatening emergencies | −0.240 | 0.208 | −0.614 | 0.134 |

| level of expertise in mass casualty incident management response | −0.281 | 0.116 | −0.632 | 0.070 |

| Poland | Coeff. | p-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| years of experience | 0.291 | 0.011 | 0.066 | 0.516 |

| level of satisfaction with employer’s training and education | −0.427 | 0.405 | −1.434 | 0.580 |

| number of practical training activities | 0.140 | 0.085 | −0.019 | 0.300 |

| number of theoretical training activities | −0.065 | 0.339 | −0.197 | 0.068 |

| number of external educational activities | 0.161 | 0.0009 | 0.066 | 0.255 |

| level of expertise in primary triage of casualties during mass casualty incident management response | −1.043 | 0.072 | −2.182 | 0.095 |

| level of expertise in practical handling of life-threatening emergencies | −1.862 | 0.0002 | −2.849 | −0.875 |

| level of expertise in mass casualty incident management response | −0.322 | 0.584 | −1.477 | 0.833 |

| Hungary | Coeff. | p-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| years of experience | −0.040 | 0.664 | −0.220 | 0.140 |

| level of satisfaction with employer’s training and education | −0.181 | 0.661 | −0.989 | 0.628 |

| number of practical training activities | 0.021 | 0.649 | −0.070 | 0.113 |

| number of theoretical training activities | 0.017 | 0.712 | −0.073 | 0.106 |

| number of external educational activities | 0.143 | 0.0001 | 0.071 | 0.215 |

| level of expertise in primary triage of casualties during mass casualty incident management response | −0.109 | 0.859 | −1.322 | 1.103 |

| level of expertise in practical handling of life-threatening emergencies | −1.194 | 0.032 | −2.283 | −0.106 |

| level of expertise in mass casualty incident management response | −1.056 | 0.079 | −2.233 | 0.122 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Titko, M.; Slemenský, M. Educational Aspects Affecting Paramedic Preparedness and Sustainability of Crisis Management: Insights from V4 Countries and the Role of Innovative Technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051944

Titko M, Slemenský M. Educational Aspects Affecting Paramedic Preparedness and Sustainability of Crisis Management: Insights from V4 Countries and the Role of Innovative Technologies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051944

Chicago/Turabian StyleTitko, Michal, and Miroslav Slemenský. 2025. "Educational Aspects Affecting Paramedic Preparedness and Sustainability of Crisis Management: Insights from V4 Countries and the Role of Innovative Technologies" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051944

APA StyleTitko, M., & Slemenský, M. (2025). Educational Aspects Affecting Paramedic Preparedness and Sustainability of Crisis Management: Insights from V4 Countries and the Role of Innovative Technologies. Sustainability, 17(5), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051944