Analysis of the Sustainable Development Pathway of Urban–Rural Integration from the Perspective of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of the Urban–Rural Fringe of Beijing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Analysis of the Current Urban–Rural Integration and Sustainable Development Situation in Beijing

3.1. Urban–Rural Integration and Sustainable Development

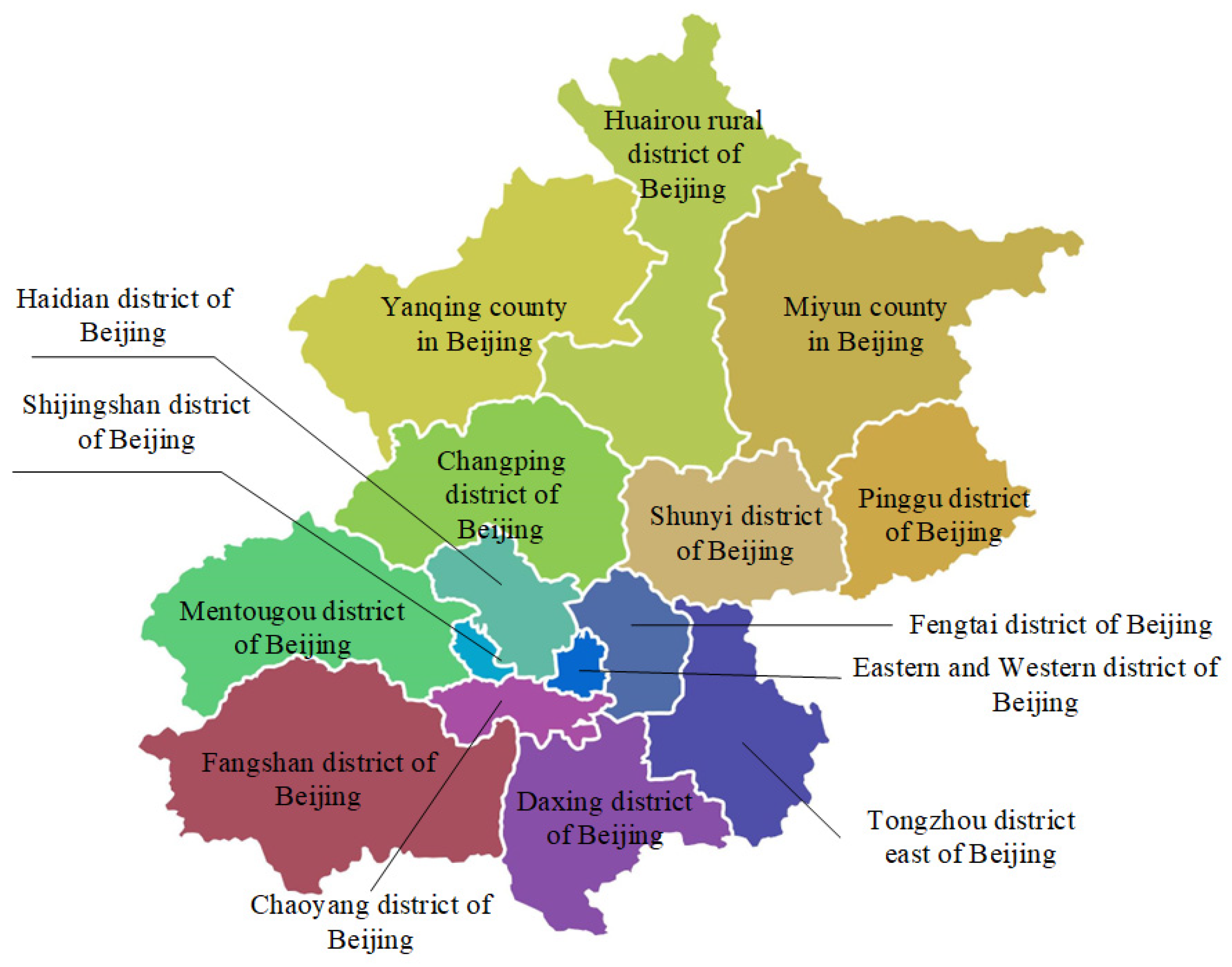

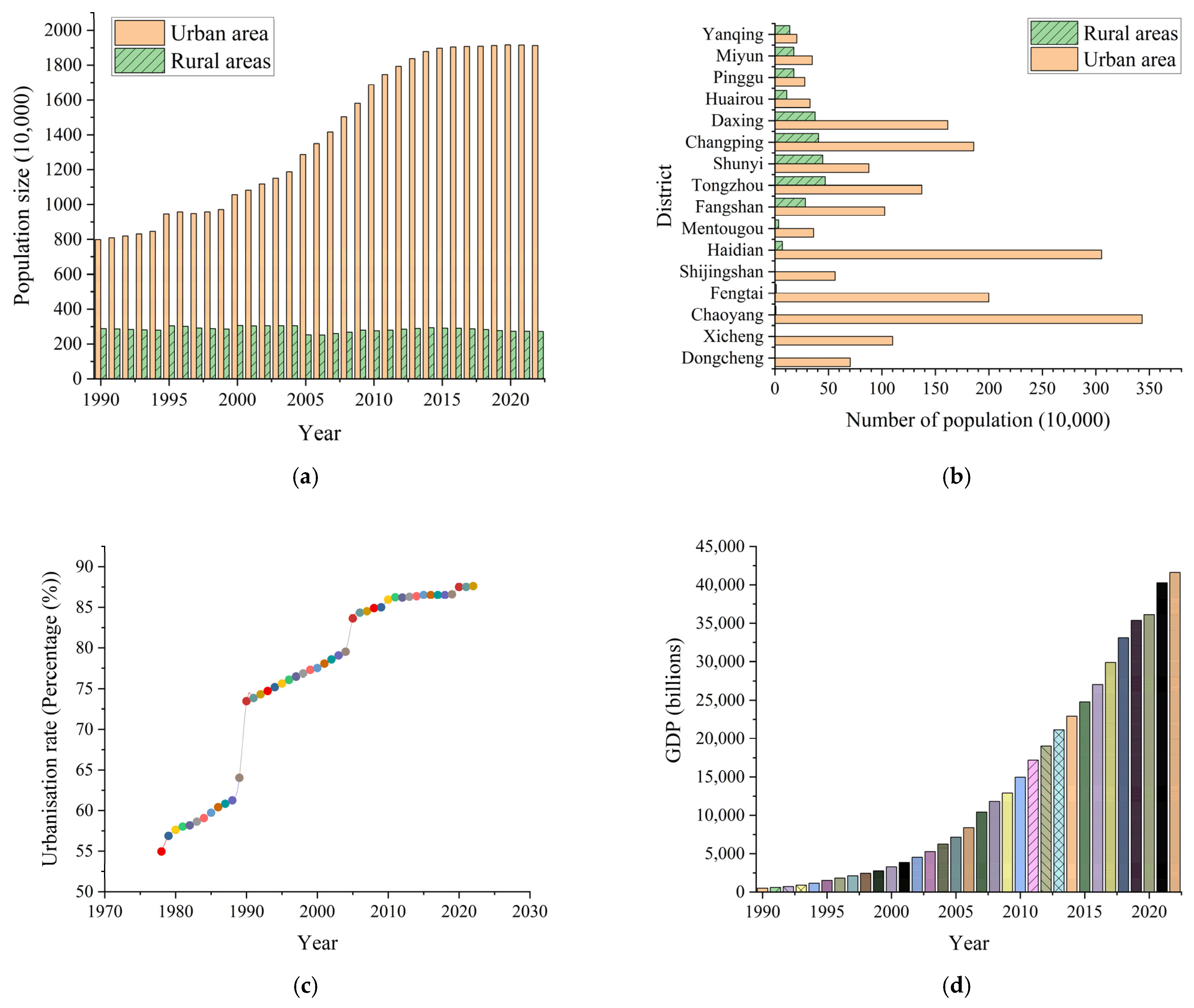

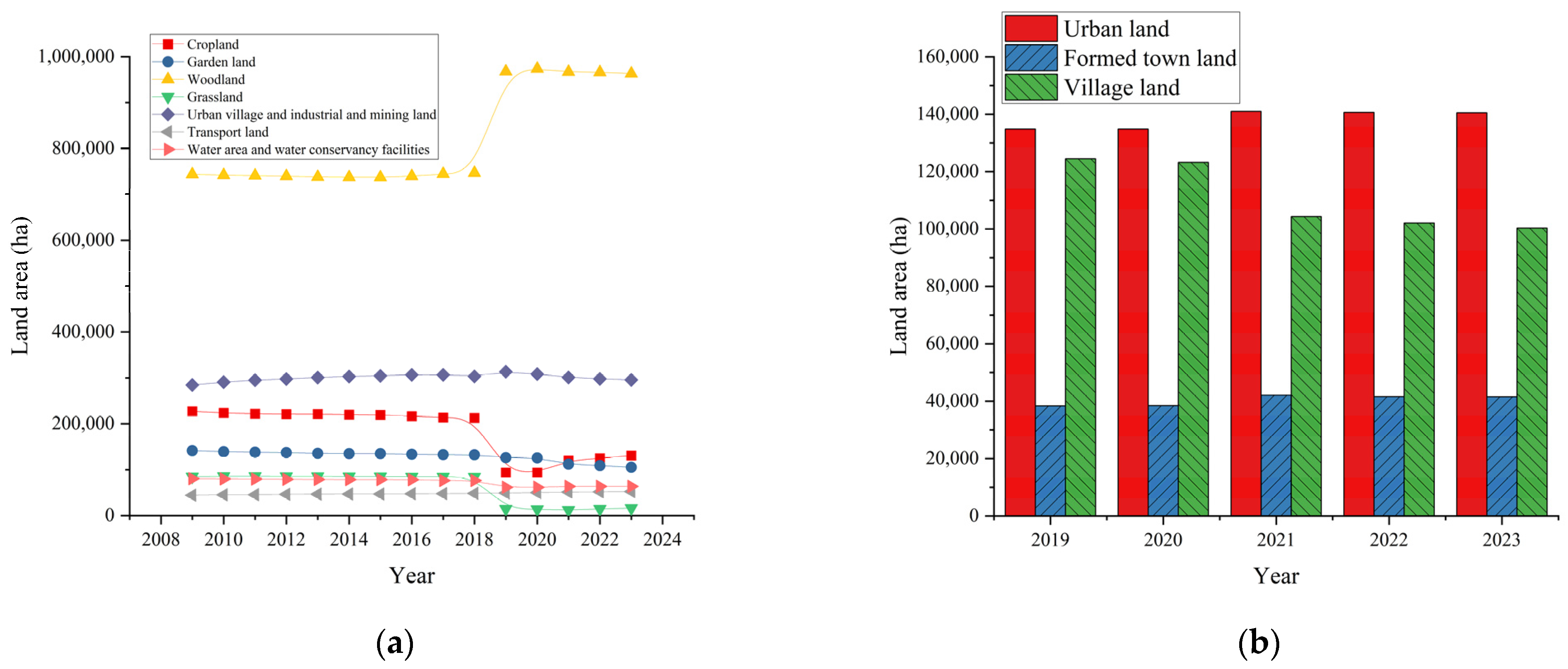

3.2. Basic Urban–Rural Integration Situation in Beijing

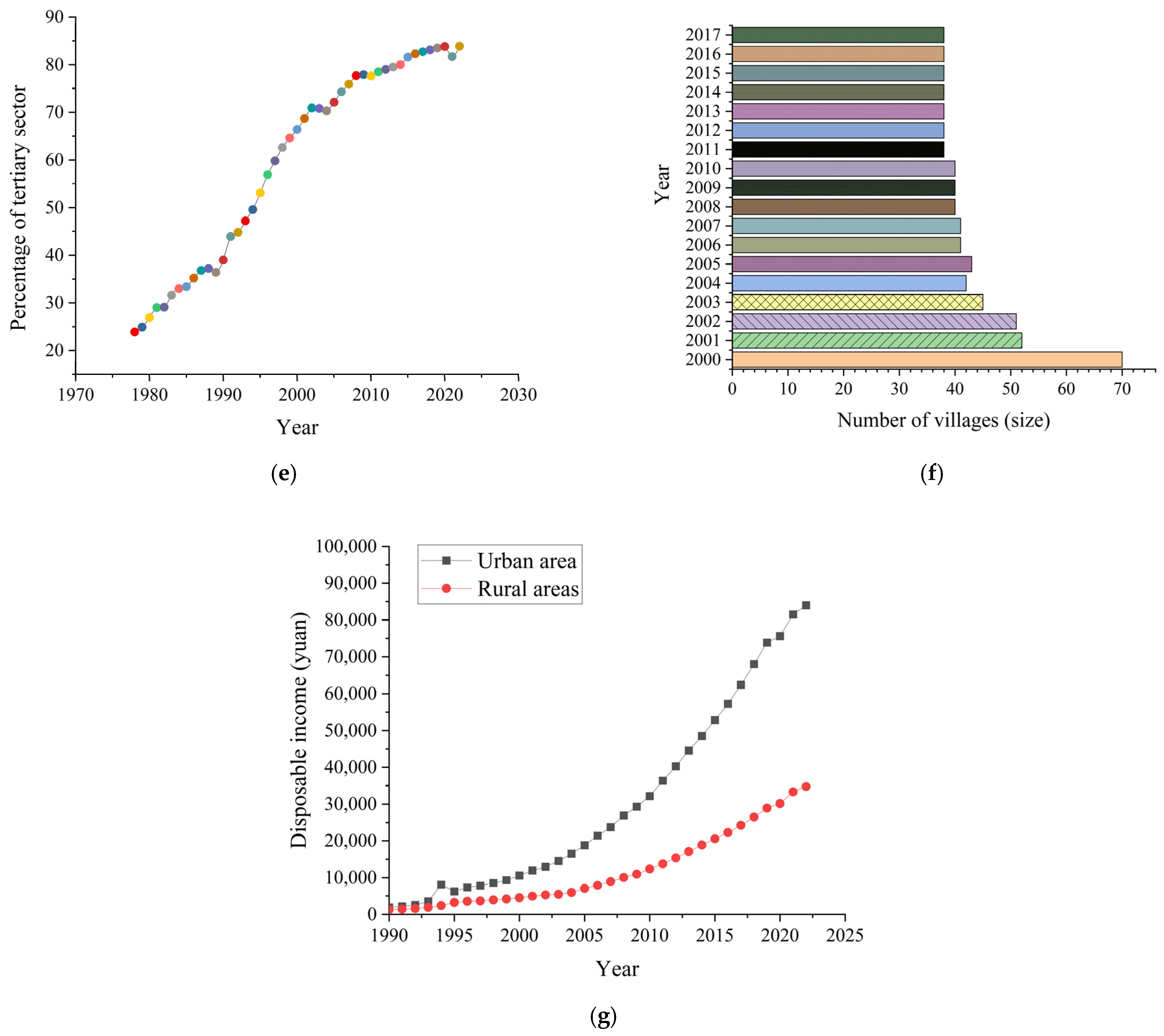

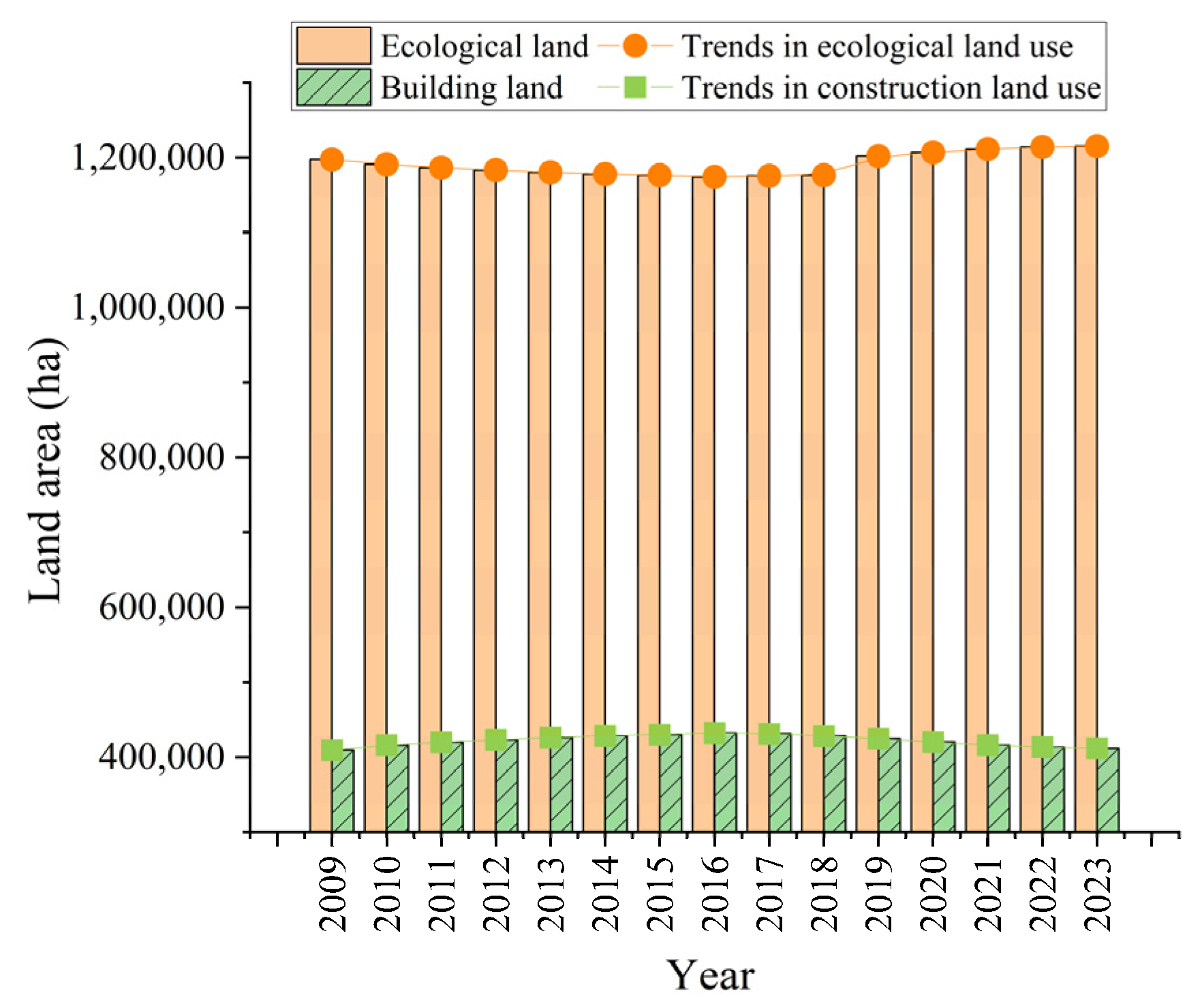

3.3. Status of Land Use Change and Ecological Environment in Beijing

4. Typical Case Analysis

4.1. Caoqiao Village, Fengtai District

4.2. Zhenggezhuang Village, Changping District

4.3. Xihoujie Village in Majuqiao Town, Tongzhou District

5. Analysis of Sustainable Development Pathways for Urban–Rural Integration Based on Spatial Planning

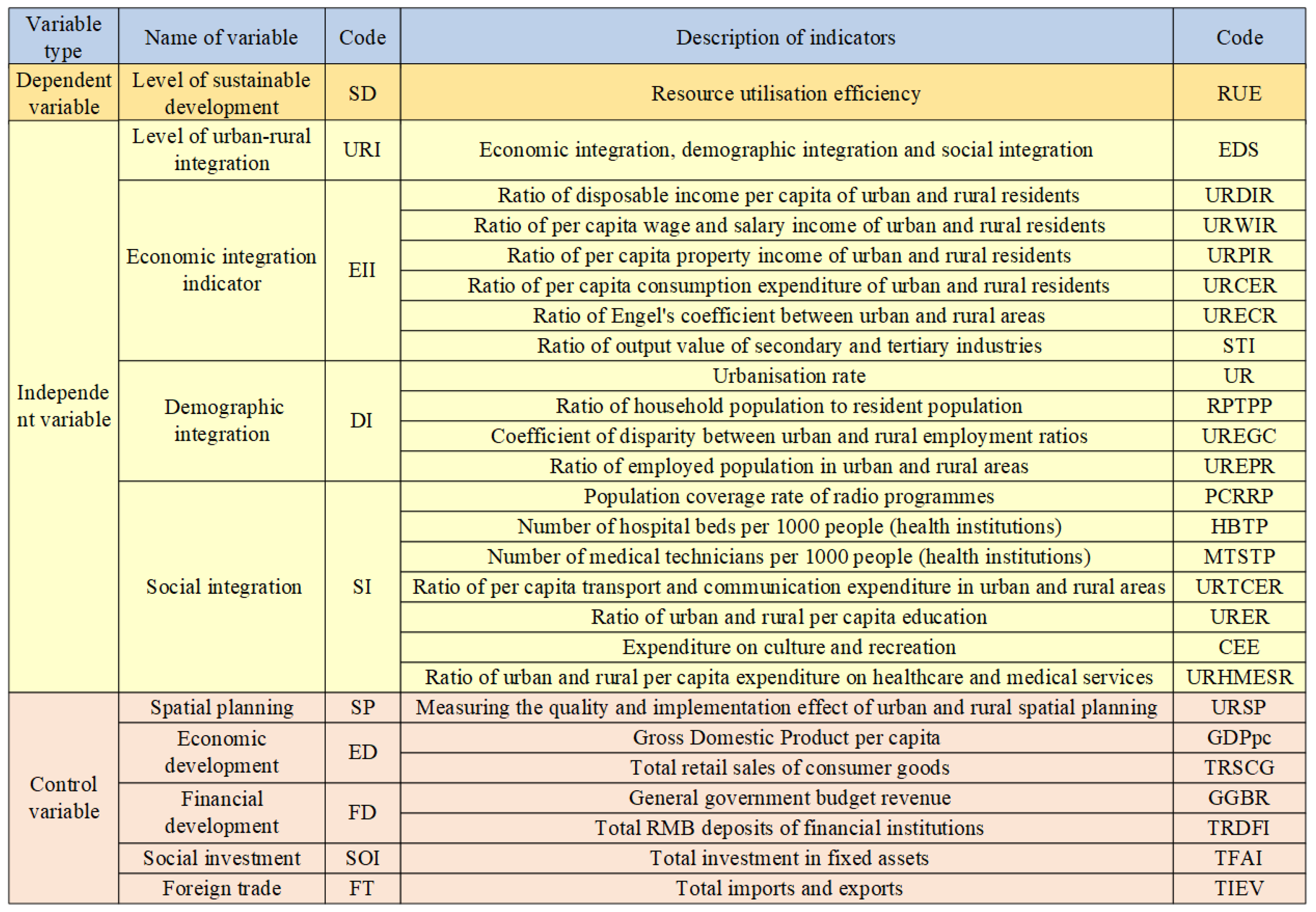

5.1. Experimental Design

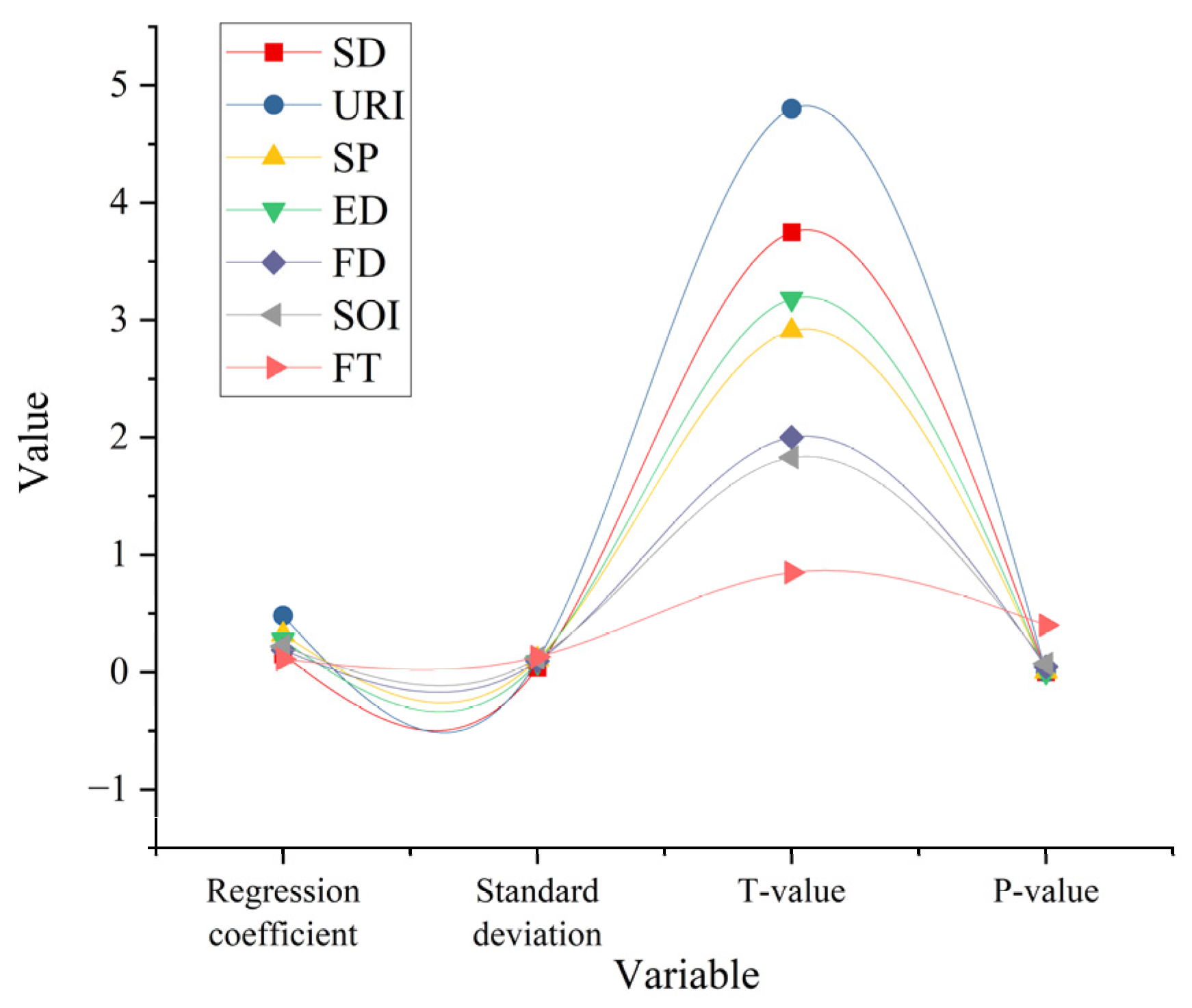

5.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing Sustainable Development of Urban–Rural Integration in Beijing

5.3. Management Suggestion and Policy Optimization Scheme Based on the Ecological Protection Red Line and Urban Development Boundary

- (1)

- Precise delimitation and dynamic adjustment of ecological protection red lines.

- (2)

- Differentiated zoning management to optimize urban development boundaries.

- (3)

- Establishing an ecological compensation mechanism to promote coordinated urban–rural development.

- (4)

- Promoting the construction of ecologically friendly infrastructure.

- (5)

- Strengthening public participation and ecological education to improve social governance effectiveness.

- (6)

- Cross-departmental collaborative governance to enhance policy implementation efficiency.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wojewodzki, M.; Wei, Y.; Cheong, T.S.; Shi, X. Urbanisation, Agriculture and Convergence of Carbon Emissions Nexus: Global Distribution Dynamics Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Jin, Y. How Can Large-Scale Housing Provision in the Outskirts Benefit the Urban Poor in Fast Urbanising Cities? Case Beijing Cities 2023, 132, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, L.; Guo, Y. Land Use Change and Its Driving Factors in the Rural-Urban Fringe of Beijing: A Production-Living-Ecological Perspective. Land 2022, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Z. How Does Urbanisation Affect the Evolution of Territorial Space Composite Function? Appl. Geogr. 2023, 155, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Pereira, P. Impacts of Urbanisation on Vegetation Dynamics in Chinese Cities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Sun, X.; Liao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, P.; Liu, Q. How Do Ecosystem Services Evolve across Urban–Rural Transitional Landscapes of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region in China: Patterns, Trade-Offs, and Drivers. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 1125–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z. Spatial Pattern of Urban-Rural Integration in China and the Impact of Geography. Geogr. Sustain. 2023, 4, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.M.; Schareika, N.; Dittrich, C.; Schlecht, E.; Sauer, D.; Buerkert, A. Rurbanity: A Concept for the Interdisciplinary Study of Rural-Urban Transformation. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1739–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özatağan, G.; Eraydin, A. Binaries Again! Revisiting the Urban-Rural Question through Geographies of Discontent. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, G.; Shen, H. The Influence of Tourism’s Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity on the Urban–Rural Relationship: A Case Study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Xu, H. Urban–Rural Integration and Poverty: Different Roles of Urban–Rural Integration in Reducing Rural and Urban Poverty in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Xi, Z.; Peng, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X. Research on Sustainable Urban–Rural Integration Development: Measuring Levels, Influencing Factors, and Exploring Driving Mechanisms—Taking Eight Cities in the Greater Bay Area as Examples. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Liu, A.; Narahara, T. The Integration of Dual Evaluation and Minimum Spanning Tree Clustering to Support Decision-Making in Territorial Spatial Planning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H.; Guo, R. Assessment and Analysis of the Balance between Economic Development and Ecological Environment Protection and Its Implementation Strategy Derived from Spatial Planning—Take Three Heterogeneous and Representative Provinces in China as an Example. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Lin, X.; Lu, Y.; Sun, J. Rural territorial types in urban and rural integrated areas taking Jiangsu Province in China as an example. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 18903–18928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihle, T.; Jahr, E.; Martens, D.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S. Health Effects of Participation in Creating Urban Green Spaces—A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Roura, J.R. Population Imbalances in Europe. Urban Concentration versus Rural Depopulation. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.S.; Nisar, U.; Warsi, S.H.; Billah, M.M.; Karkkulainen, E.A. Mapping the Disparities between Urban and Rural Areas in the Global Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals, Economic and Social Aspects of Global Rural-Urban Migration. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 2052–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omweri, F.S. A Systematic Literature Review of E-Government Implementation in Developing Countries: Examining Urban-Rural Disparities, Institutional Capacity, and Socio-Cultural Factors in the Context of Local Governance and Progress towards SDG 16.6. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 1173–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Adukia, A.; Brown, D.L.; Christiaensen, L.; Evans, D.K.; Haakenstad, A.; McMenomy, T.; Partridge, M.; Vaz, S.; Weiss, D.J. Economic and Social Development along the Urban–Rural Continuum: New Opportunities to Inform Policy. World Dev. 2022, 157, 105941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Wu, Y. Research on Effects of Integration of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Industries in Rural Areas of Developing Countries: An Approach of Rural Capital Subsidies. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2024, 31, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. Can Agricultural Industry Integration Reduce the Rural–Urban Income Gap? Evidence from County-Level Data in China. Land 2024, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoett, P.; Scrich, V.M.; Elliff, C.I.; Andrade, M.M.; Grilli, N.D.M.; Turra, A. Global Plastic Pollution, Sustainable Development, and Plastic Justice. World Dev. 2024, 184, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Goswami, S. Theoretical Framework for Assessing the Economic and Environmental Impact of Water Pollution: A Detailed Study on Sustainable Development of India. J. Future Sustain. 2024, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; He, D.; Wang, R.; Han, Z.; Deng, X. Assessment of Natural Resource Endowment and Urban-Rural Integration for Sustainable Development in Xinjiang, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 142046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wen, C.; Fang, X.; Sun, X. Impacts of urban-rural integration on landscape patterns and their implications for landscape sustainability: The case of Changsha, China. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Spatial path to achieve urban-rural integration development–analytical framework for coupling the linkage and coordination of urban-rural system functions. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Xie, Y.; Wei, R.; Ye, C.; Wang, H. Application of Machine Learning in Ecological Red Line Identification: A Case Study of Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. Diversity 2024, 16, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Ma, N.; Xiong, X. The Impact of Urban Growth Boundary on Urban Sprawl: Evidence from China. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Huo, J.; Zhu, W.; Ma, R.; Xue, H.; Wang, Z. Comprehensive Evaluation of Urban Development Suitability Based on Constraints and Development Factors: A Case Study of the Central Urban Area of Zhengzhou, China. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2024, 48, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, A. Analysis of the Sustainable Development Pathway of Urban–Rural Integration from the Perspective of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of the Urban–Rural Fringe of Beijing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051857

Zhang A. Analysis of the Sustainable Development Pathway of Urban–Rural Integration from the Perspective of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of the Urban–Rural Fringe of Beijing. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051857

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Anni. 2025. "Analysis of the Sustainable Development Pathway of Urban–Rural Integration from the Perspective of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of the Urban–Rural Fringe of Beijing" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051857

APA StyleZhang, A. (2025). Analysis of the Sustainable Development Pathway of Urban–Rural Integration from the Perspective of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of the Urban–Rural Fringe of Beijing. Sustainability, 17(5), 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051857