Evaluating Perceptions of the Natural Environment in Relation to Outdoor Activities for a Healthy and Sustainable Life: A Delphi Methodological Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What are the most relevant socioeconomic, health-related, environmental and social factors involved in the positive perception of nature in outdoor activities?

- (b)

- What is the positive impact of different activities in natural environments on well-being?

- (c)

- Is the Delphi method adequate in developing a questionnaire to determine the factors involved in the positive perception of nature in outdoor activities?

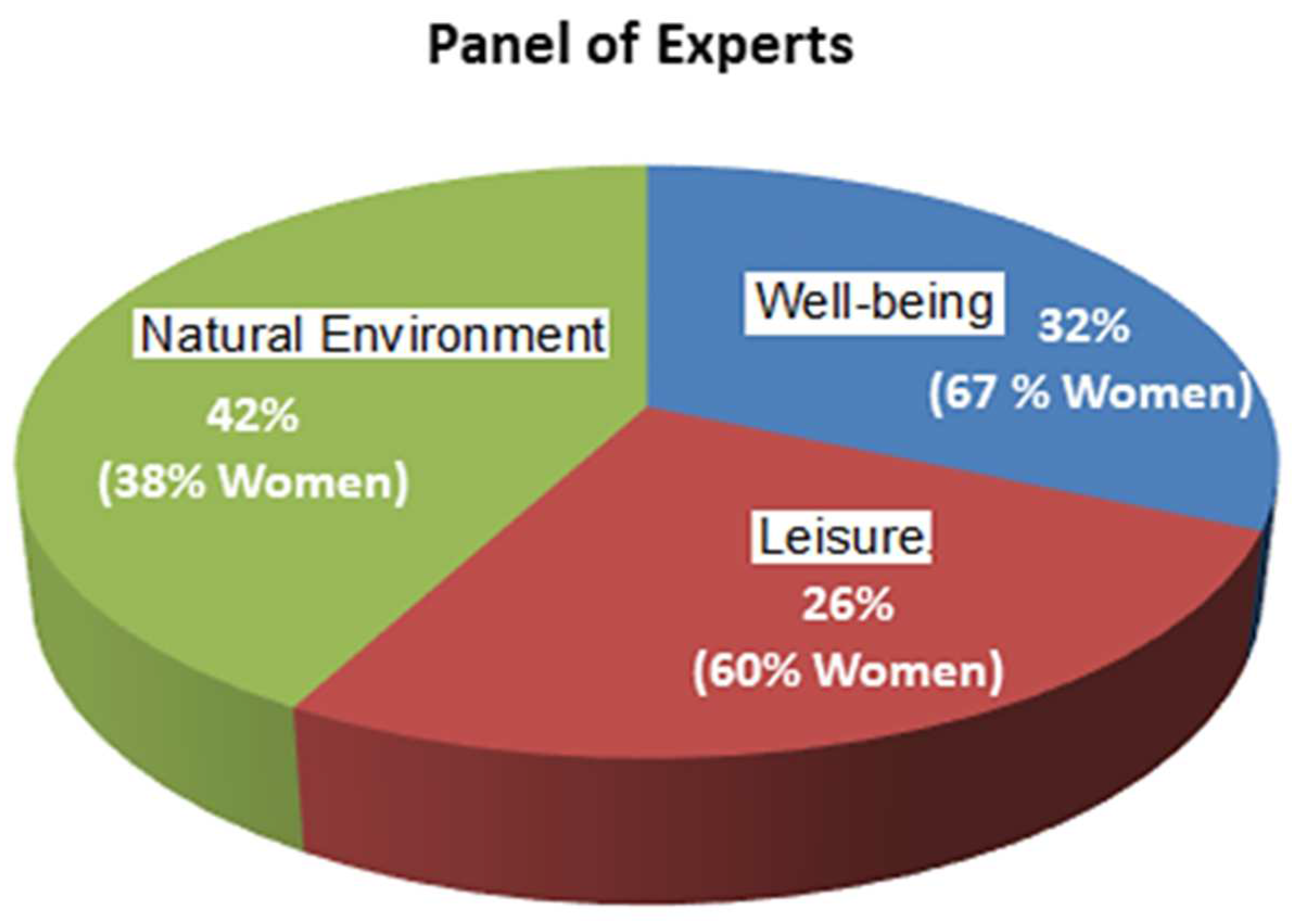

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Design

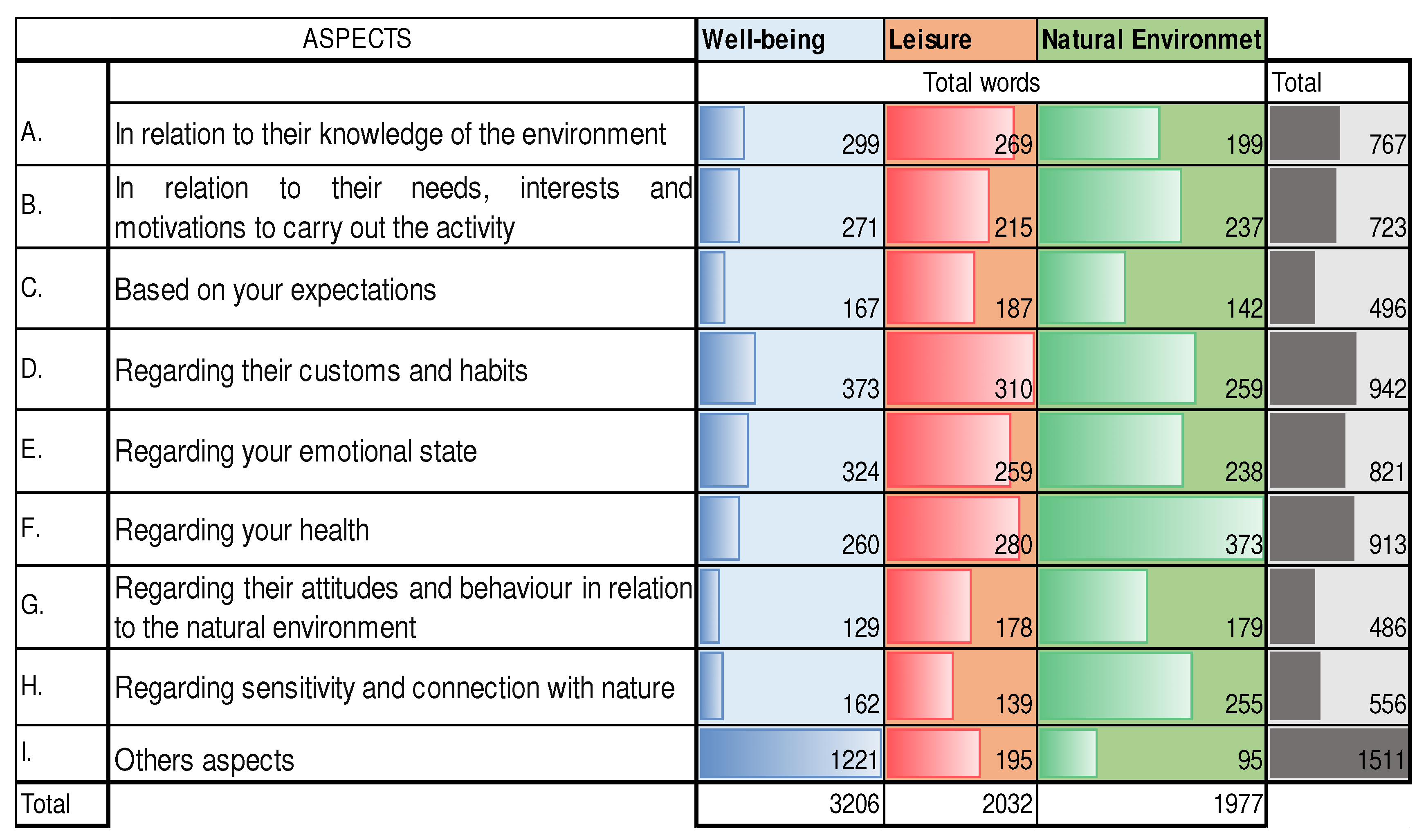

3.2. First Round of the Panel of Delphi Experts: Essential Aspects

- In relation to their knowledge of the environment.

- In relation to their needs, interests and motivations to carry out the activity.

- Based on their expectations.

- Regarding their customs and habits.

- Regarding their emotional state.

- Regarding their health.

- Regarding their attitudes and sustainable behaviours in the natural environment.

- Regarding their sensitivity and connection with nature.

- Other aspects.

3.3. Second Round of the Panel of Delphi Experts: Questionnaire

- On the need to carry out any activity in natural environments.

- The priority of activities in nature over other types of leisure.

- The type of activity in contact with nature.

- The type of natural environment.

- The situation and proximity of the natural environment.

- Accessibility to the natural environment.

- The frequency of the activity.

- The duration of the activity.

- The activity is carried out in company or alone.

- The highlights of the experience in the relationship with nature.

- Satisfaction with the activity.

- Proposals to improve the activity.

- Activity recommendation and reasons.

- Wondering if contact with nature influences physical and emotional well-being.

- More identified with an anthropocentric or biophilic sense of nature.

- Information media for discovering the natural environment.

- Valuation of the natural environment.

- How to improve the quality of the natural environment.

- Knowledge of species in the natural environment.

- Knowledge of legal protection standards for the natural environment.

- Reason for doing outdoor activities in contact with nature.

- Requirements of the natural environment to achieve the objective.

- Emotional state before starting the activity.

- Emotional state when performing the activity.

- Emotional state after performing the activity.

- Senses most used in activities in contact with nature.

- If it is more rewarding on a sunny day.

- If the activity in contact with nature is therapeutic.

- Health benefits.

- Share the experience on social networks.

- Mobile phone disconnection when in nature.

- Use of mobile devices to know the natural environment, take photos and videos in nature, to check your vital signs or other health indicators.

- The cost of the activity an obstacle.

- Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic in increasing activities in natural environments.

- About daily sustainable behaviour.

- About ecological awareness.

- About how this activity has changed the relationship with nature.

- About environmental concerns.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

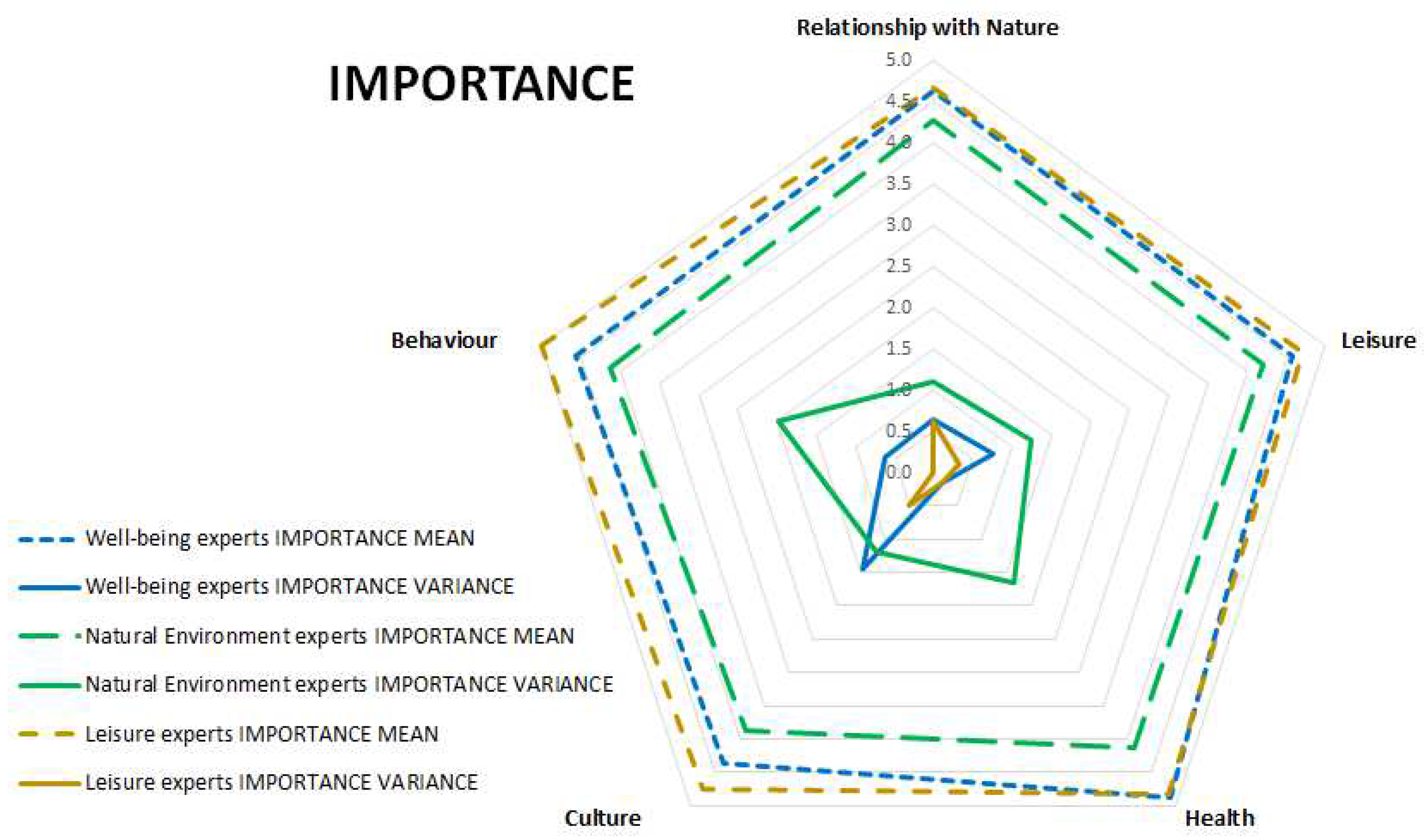

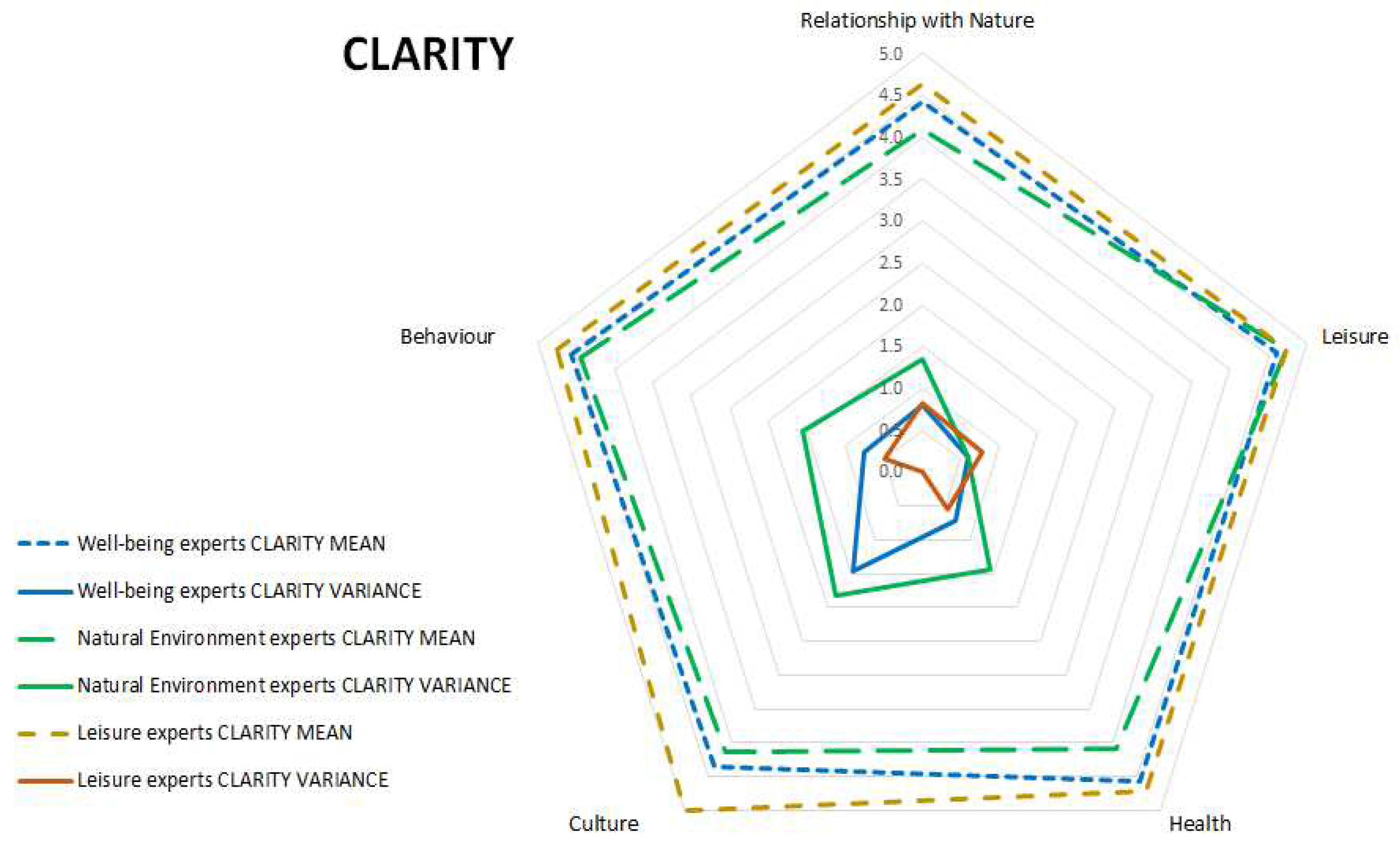

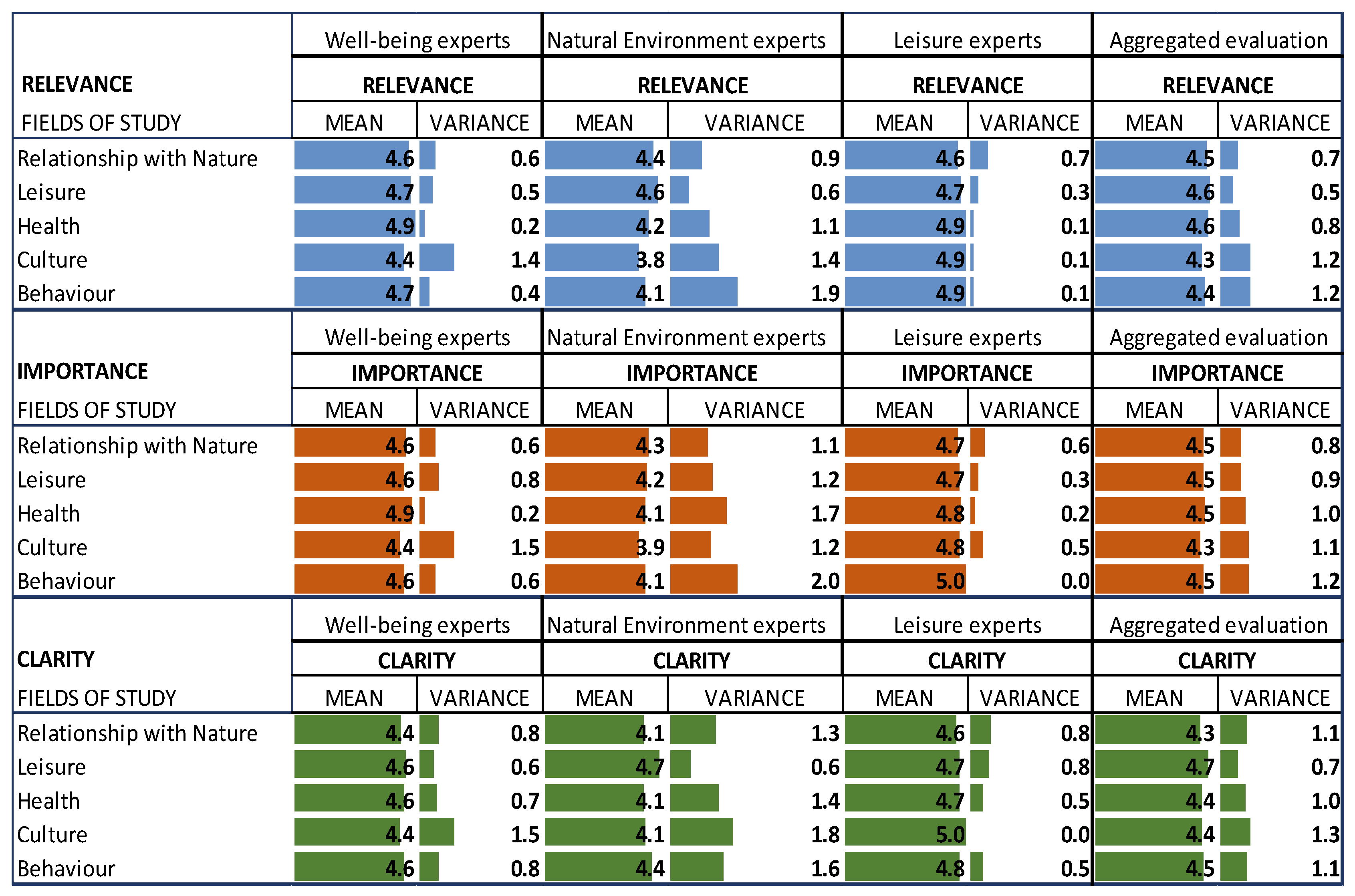

Appendix A. Assessment of the Issues Raised by the Panel of Experts

References

- Hartig, T.; van den Berg, A.E.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Tomalak, M.; Bauer, N.; Hansmann, R.; Ojala, A.; Syngollitou, E.; Carrus, G.; van Herzele, A.; et al. Forests, Trees and Human Health; Springer Science & Business Media B.V: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Global synthesis reveals heterogeneous changes in connection of humans to nature. One Earth 2023, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullone, E. The biophilia hypothesis and life in the 21st century: Increasing mental health or increasing pathology? J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B.; Yang, W.; Gao, Y. Effect of Nature Space on Enhancing Humans’ Health and Well-Being: An Integrative Narrative Review. Forests 2024, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.A.; Ferguson, M.D.; Rodrigues, K.; Evensen, D.; Caraynoff, A.R.; Persson, K.; Porter, J.B.; Eisenhaure, S. The role of health and wellbeing in shaping local park experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.J.; Dickie, J.; Bartie, P.J.; Oliver, D.M. Health and wellbeing (dis) benefits of accessing inland blue spaces over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 252, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.V.; Scopelliti, M. Empirical research in environmental psychology. Past, present, and future. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X. Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e313–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.H. Therapeutic influences of plants in hospital rooms on surgical recovery. HortScience 2009, 44, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, G.; Dadvand, P.; Sanesi, G. Editorial: The Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions to Psychological Health. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Matos, M.; Gonçalves, M. Nature and human well-being: A systematic review of empirical evidence from nature-based interventions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 3397–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimi, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenschenk, B.; Thomann, A.; McClure, M.; Davies, L.; Gregory, M.; Dettweiler, U.; Inglés, E. Benefits of Outdoor Sports for Society. A Systematic Literature Review and Reflections on Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, R.J.; Carballeira, M. Contact with nature and personal well-being. Psyecology 2010, 1, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Giuliani, M.V. Choosing restorative environments across the lifespan: A matter of place experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, K.K.; Ayalon, O.; Eshet, T.; Nathan, O. The influence of social context and activity on the emotional well-being of forest visitors: A field study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 94, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Frías, M.; Gaxiola, J.; Tapia, C.; Fraijo, B.; Corral, N. Ambientes positivos. In Ideando Entornos Sostenibles Para el Bienestar Humano y la Calidad Ambiental; Pearson: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Štreimikienė, D. Environmental indicators for the assessment of quality of life. Intellect. Econ. 2015, 9, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Shearwater Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why is nature beneficial? The role of connectedness to nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirana-Malaret, M.; Miró, A.; Camacho, A.; Gesse, A.; McEwan, K. A Multi-Country Study Assessing the Mechanisms of Natural Elements and Sociodemographics behind the Impact of Forest Bathing on Well-Being. Forests 2023, 14, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Maggini, V.; Gallo, E.; Mascherini, V.; Firenzuoli, F.; Meneguzzo, F. Demographic, Psychosocial, and Lifestyle-Related Characteristics of Forest Therapy Participants in Italy: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Tzortzi, J.N. Design guidelines for healing gardens in the general hospital. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1288586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calaza, P. Guía de Infraestructura Verde Municipal: Red de Gobiernos Locales + Biodiversidad, FEMP, ASEJA and AEPJP. 2019. Available online: https://redbiodiversidad.es/sites/default/files/GUIA_Biodiversidad_CAPITULOS1_5.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suppakittpaisarn, P.; Wu, C.C.; Tung, Y.H.; Yeh, Y.C.; Wanitchayapaisit, C.; Browning, M.H.; Chun-Yen, C.; Sullivan, W.C. Durations of virtual exposure to built and natural landscapes impact self-reported stress recovery: Evidence from three countries. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 19, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Classic Edition published by Psychology Press 711 Third Avenue; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 10017. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems; Boston Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H.; Nasar, J.L. Evaluating environmental scenes using dynamic versus static displays. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balling, J.D.; Falk, J.H. Development of visual preference for natural environments. Environ. Behav. 1982, 14, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments-healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M.L.; Aviste, R. Relationships between people and nature: Nature Connectedness and Relational Environmental Values. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2024, 62, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.R. Gone barefoot lately? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Groenewegen, P.P. Physical activity as a possible mechanism behind the relationship between green space and health: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, A.; Veloso, S. Outdoor exercise, well-being and connectedness to nature. Psico 2014, 45, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Ecological Psychology in Context: James Gibson, Roger Braker, and the Legacy of William James’s Radical Empiricism; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Lyons, M.; Vione, K.C.; Norton, B. Effect of Nature Walks on Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M.; Finkel, L. Encuestas por Internet y nuevos procedimientos muestrales. In Panorama Social, Número 30. Segundo semester; Fundación de las Cajas de Ahorros: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn, D. Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, B.; Weigelt, O.; Hergert, J.; Gurt, J.; Gelléri, P. The Use of Snowball Sampling for Multi Source Organizational Research: Some Cause for Concern. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 635–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; Loreau, M.; de Mazancourt, C.; Singer, M.C.; Parmesan, C. Psychological and physical connections with nature improve both human well-being and nature conservation: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 277, 109842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.A.; Barbett, L.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro-nature conservation behaviours. People Nat. 2020, 2, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, M.E.; Lena-Acebo, F.J. Aplicación del método Delphi en el diseño de una investigación cuantitativa sobre el fenómeno FABLAB EMPIRIA. Rev. Metodol. Cienc. Soc. 2018, 40, 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S. Utilizing and Adapting the Delphi Method for Use in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 1609406915621381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M.; Spranger, J. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences: A Map. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengual-Andrés, S.; Roig-Vila, R.; Mira, J. The Delphi method validates the design of a questionnaire and provides a suitable tool for future studies on digital competence in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2016, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Pascual, K.; Garcia-Pérez, I.; Zorita, S.; García-Madruga, C.; Cantergiani, C.; Skodra, J.; Iraurgi, I. A Proposal of a Tool to Assess Psychosocial Benefits of Nature-Based Interventions for Sustainable Built Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N.; Hugé, J.; Sutherland, W.; McNeill, J.; Van Opstal, M.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Koedam, N. The Delphi technique in ecology and biological conservation: Applications and guidelines. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles Garrote, P.; del Carmen Rojas, M. La validación por juicio de expertos: Dos investigaciones cualitativas en Lingüística aplicada. Rev. Nebrija Lingüística Apl. A Enseñanza Leng. 2015, 18, 124–139. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.M.; Fernández, F. Diseño de encuesta sobre las metodologías y la actividad científica de los equipos de investigación. Metodol. Encuestas 2004, 6, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Giannarou, L.; Zervas, E. Using Delphi technique to build consensus in practice. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. 2014, 9, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flostrand, A.; Pitt, L.; Bridson, S. The Delphi technique in forecasting– A 42-year bibliographic analysis (1975–2017). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Yang, J.; Chin, M.-K.; Sullivan, L.; Durstine, J.L.; Violant-Holz, V.; Demirhan, G.; Oliveira, N.R.C.; Popeska, B.; Kuan, G.; et al. Physical Activity among Adults Residing in 11 Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesser, I.A.; Nienhuis, C.P. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physical Activity Behavior and Well-Being of Canadians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.J. Stress, anxiety, leisure changes, and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Leis. Res. 2023, 54, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoić, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Sanesi, G.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, C.; Petersen, E.; MacIntyre, T. Natural environments, psychosocial health, and health behaviors in a crisis. A scoping review of the literature in the COVID-19 context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 88, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ramos, J.; García- Fernández, J.; Sampedro Ortega, Y.; Pardellas-Santiago, M.; Majadas-Andray, J. Educación Ambiental Para la Sostenibilidad en el Corazón de las Políticas Públicas: Recorrido Histórico, Buenas Prácticas y Recomendaciones Para su Transversalización. OAPN. 2024. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/ceneam/recursos/documentos/Informe_EAS_19_Jun.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Área de Promoción de la Salud y Equidad. Subdirección General de Promoción de la Salud y Prevención. Dirección General de Salud Pública. Recomendaciones Para el Diseño de Estrategias de Salud Comunitaria en Atención Primaria a Nivel Autonómico. 2022. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/entornosSaludables/saludComunitaria/documentosTecnicos/docs/recomendaciones_estrategia_salud_comunitaria.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Ubalde, M. Isglobal. 2021. Available online: https://www.isglobal.org/healthisglobal/-/custom-blog-portlet/-como-impacta-la-planificacion-urbana-en-nuestra-salud-nuestra-salud-y-la-del-planeta-dependen-del-diseno-de-las-ciudades (accessed on 1 February 2022).

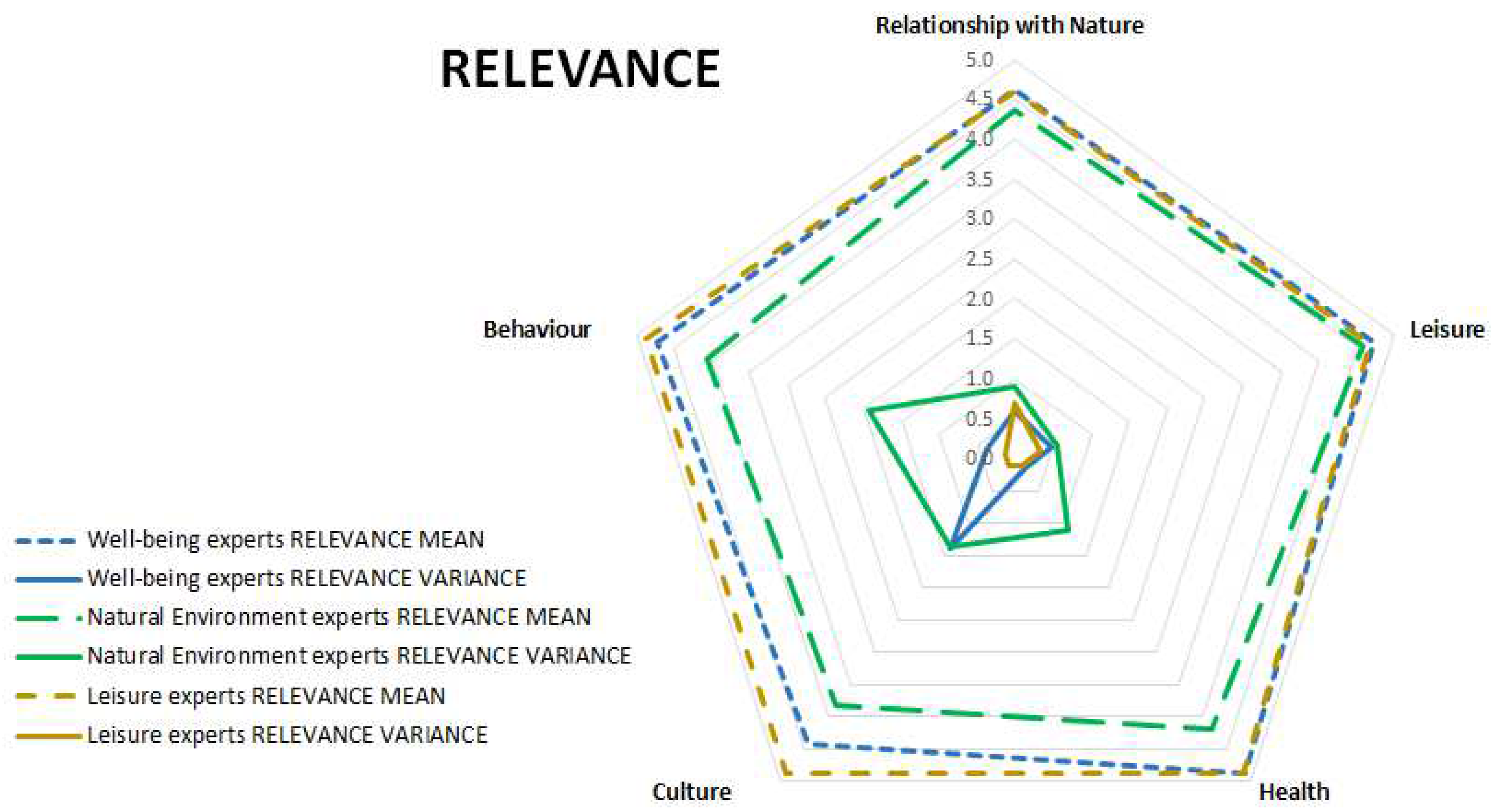

| Field of Study | Questionnaire Items |

|---|---|

| Relationship with nature | 1–6; 10–13; 16–22; 26–27; 33; 37 |

| Leisure | 7–9; 30–33 |

| Health | 14; 23–25; 28–29 |

| Culture | 15; 38 |

| Behaviour | 35; 36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buceta-Albillos, N.; Ayuga-Téllez, E. Evaluating Perceptions of the Natural Environment in Relation to Outdoor Activities for a Healthy and Sustainable Life: A Delphi Methodological Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051847

Buceta-Albillos N, Ayuga-Téllez E. Evaluating Perceptions of the Natural Environment in Relation to Outdoor Activities for a Healthy and Sustainable Life: A Delphi Methodological Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051847

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuceta-Albillos, Natividad, and Esperanza Ayuga-Téllez. 2025. "Evaluating Perceptions of the Natural Environment in Relation to Outdoor Activities for a Healthy and Sustainable Life: A Delphi Methodological Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051847

APA StyleBuceta-Albillos, N., & Ayuga-Téllez, E. (2025). Evaluating Perceptions of the Natural Environment in Relation to Outdoor Activities for a Healthy and Sustainable Life: A Delphi Methodological Approach. Sustainability, 17(5), 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051847