Enhancing the Sustainable Development of the ASEAN’s Digital Trade: The Impact Mechanism of Innovation Capability

Abstract

1. Introduction

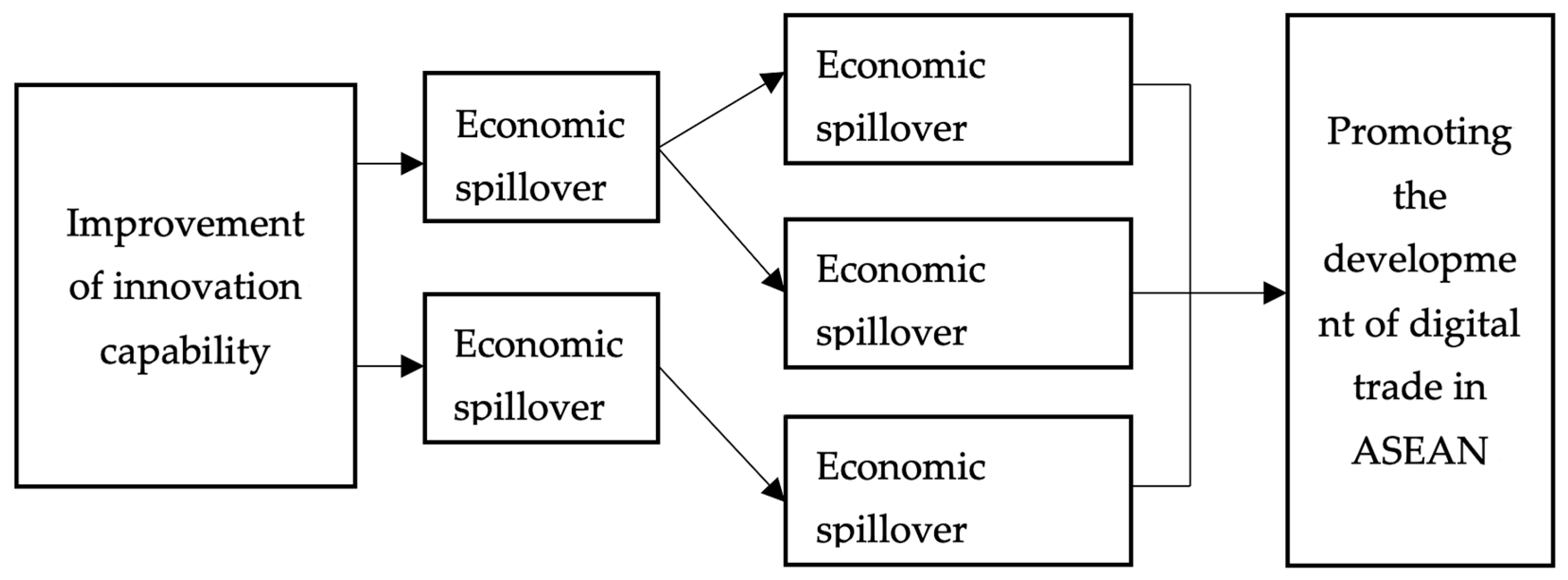

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Hypotheses

2.1. The Current Situation and Relationship Between Innovation Capability and Digital Trade

Current Status of ASEAN Innovation Capability

2.2. Current Status of ASEAN Digital Trade Development

2.2.1. Emphasis on Digital Trade Development

2.2.2. The Rapid Development of E-Commerce

2.2.3. The Increasing Usage and Popularity of the Internet

2.3. Relationship Between Innovation Capability and Digital Trade

2.3.1. Relationship Between Innovation Capability and Digital Product Trade

2.3.2. Relationship Between Innovation Capability and Digital Service Trade

2.3.3. Regulatory Mechanism of Digitalization Level on the Relationship Between Innovation and Digital Trade

2.4. Factors Influencing Digital Trade

3. Methodology and Results

3.1. Analysis of Differences in Digital Trade Among ASEAN Countries

3.1.1. Calculating the Proportion of Each Group or Individual

3.1.2. Calculating the Inequality of Each Group

3.1.3. Calculating the Theil Index

- (a)

- The digital trade gap among ASEAN countries initially widened and then narrowed

- (b)

- Significant differences in digital product trade import and export

- (c)

- The gap in digital service trade continues to narrow

3.2. Variable Selection and Data Sources for Empirical Analysis

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables and Control Variables

3.2.3. Regression Analysis

+ β5goverit + β6reguit + β7politicalit + β8voiceit + β9controlit + εit

+ β5goverit + β6reguit + β7politicalit + β8voiceit + β9coutrolit + εit

+ β5goverit + β6reguit + β7politicalit + β8voiceit + β9coutrolit + εit

3.3. Empirical Analysis of Innovation Capability on ASEAN Digital Trade

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.3.2. Benchmark Regression Analysis

3.4. Mediation and Moderation Effect

3.4.1. Mediation Effect

3.4.2. Moderation Effect

3.5. Robustness Test

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.C.; Yang, Q. Analysis of the Current State of ASEAN Digital Trade and Prospects for China-ASEAN Digital Trade Relations. Reg. Financ. Res. 2022, 11, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. A Proposed Framework for Digital Supply-Use Tables. In Working Paper for Informal Advisory Group on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Jia, P. Does the Level of Digitalized Service Drive the Global Export of Digital Service Trade? Evidence from Global Perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 72, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Growth, Trade, and Inequality. Econometrica 2018, 86, 37–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, W.; Zhou, F. Does Digital Service Trade Boost Technological Innovation? International Evidence. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 88, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Liu, C.; Zheng, C.; Li, F. Digital Economy, Technological Innovation and High-Quality Economic Development: Based on Spatial Effect and Mediation Effect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P.; Lu, H.Y. Digital Service Trade and National Innovation Capacity: A Study of the Mediating Effect of Income Gap. Technol. Econ. 2022, 41, e0277245. [Google Scholar]

- Greaney, T.M.; Li, Y. Multinational Enterprises and Regional Inequality in China. J. Asian Econ. 2017, 48, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J. Analysis of Digital Product Trade and Its Development Strategy. Bus. Times 2009, 35, 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.R.; Wang, B.X. Research on the Evolution Mechanism and Influencing Factors of the Network Dependence in Global Digital Product Trade. Explor. Econ. Issues 2023, 10, 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dingtou Insights; Dingtou Industrial Research Institute. Blue Book of Digital Trade—Global Digital Trade Scale Measurement and Data Analysis Report (2024); Released on 20 September 2024; Dingtou Insights: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. Should We Agree on Common Standards for Digital Trade? Available online: https://icert.vn/asean-nen-thong-nhat-tieu-chuan-chung-ve-thuong-mai-so.htm (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- New Weekly. China’s Internet “Reboot” in Southeast Asia. Available online: https://www.neweekly.com.cn/article/shp0544019737 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- WIPO. Global Innovation Index 2023. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/zh/wipo-pub-2000-2023-exec-zh-global-innovation-index-2023.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Jiang, D.C.; Pan, X.W. The Impact of Digital Economy Development on Corporate Innovation Performance—Evidence from China’s Listed Companies. Shanxi Univ. J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2022, 45, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN-China Joint Statement on Facilitating Cooperation in Building a Sustainable and Inclusive Digital Ecosystem, 10 October 2024; Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Scientific. Digital Economy and the Sustainable Development of ASEAN and China; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Current Situation and Prospects of Digital Infrastructure Construction in ASEAN Countries. S. Asia Southeast Asia Res. 2022, 5, 90–101+156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitz, M.; Waldfogel, J. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the Digital Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Cooperation Center. ASEAN Digital Economy and China–ASEAN “Digital Silk Road” Construction. Available online: https://www.icc.org.cn/trends/mediareports/1618.html (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- ASEAN Business Environment Report. Available online: https://www.ccpit.org (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Google; Temasek; Bain & Company. e-Conomy SEA 2019: Southeast Asia’s $100 Billion Internet Economy. Available online: https://blog.google/documents/47/SE/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- People’s Daily. Steady Economic Growth in ASEAN. People’s Daily, 29 February 2024.

- Temasek. Google-Temasek-Bain e-Conomy SEA 2023 Report. Available online: https://www.temasek.com.sg/content/dam/temasek-corporate/news-and-views/resources/reports/google-temasek-bain-e-conomy-sea-2023-report.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- HSBC. How Chinese Capital Can Seize a $4 Trillion Consumer Market Opportunity as ASEAN Accelerates New Economy Adoption Amid the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.business.hsbc.com.cn/zh-cn/campaigns/belt-and-road/asean-story-3 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- World Bank. GDP (Current US$). Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD/1ff4a498/Popular-Indicators (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Hou, J.; Liu, C. Does Digital Trade Improve Innovation Capacity in Countries along the Belt and Road? A Mediating Effect Analysis Based on Industrial Upgrading. Price Mon. 2024, 4, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliansky, A.L.; Hilbert, M. Digital Technology and International Trade: Is It the Quantity of Subscriptions or the Quality of Data Speed That Matters? Telecommun. Policy 2017, 41, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtradeplus.un.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Liu, D.X.; Zhong, X.Y. Independent Innovation, Technology Introduction, and Added-Value Trade Network Position. Stat. Decis. 2020, 36, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Improving Digital Connectivity for E-Commerce: A Policy Framework and Empirical Note for ASEAN. Policy Paper 2020.

- Yue, Y.S.; Li, R. Comparison of Digital Service Trade International Competitiveness and Its Implications for China. China Circul. Econ. 2020, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Huo, Q. The Enterprise Innovation Effect of Opening Up Digital Service Trade. Econ. Dyn. 2023, 1, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.L. Service Innovation and the Competitiveness of China’s Service Trade. Ph.D. Thesis, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.M.; Zhu, Z.H. Technological Innovation, Industrial Upgrading, and International Digital Trade Development: A Panel VAR-Based Analysis. J. Fujian Tech. Norm. Univ. 2021, 39, 485–492+537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Reflections on the Development of the Digital Economy. Mod. Telecommun. Technol. 2017, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z. Research on the Integration and Development of Hunan’s New Generation Information Technology Industry and Manufacturing Industry. Coop. Econ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 10, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. Research on the Relationship Between the Development Level of the Information Service Industry and the Technological Innovation Capability of the Manufacturing Industry. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.C.; Jin, J.M.; Jiang, Y.S. Digital Platform Capability and Manufacturing Service Innovation Performance—The Chain Mediating Roles of Network Capability and Value Co-Creation Online. Sci. Technol. Prog. Countermeas. 2023, 40, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Tan, H. Research on the Mechanism and Path of Digital Platform Participation in Value Co-Creation of Services. Price Theory Pract. 2023, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.Q. Multiple Impacts of the Digital Economy on China’s Foreign Trade Competitiveness. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2022, 458, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Zhou, W.Y.; Tian, Z.T. Digital Trade: Development Trends, Impacts, and Countermeasures. Int. Econ. Rev. 2014, 6, 131–144+8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Liu, H. Global Digital Trade Development Trends, Restrictive Factors, and China’s Strategies. Theor. J. 2018, 5, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlman, C.; Mealy, S.; Wermelinger, M. Harnessing the Digital Economy for Developing Countries. In OECD Development Centre Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; Volume 334. [Google Scholar]

- Ferencz, J. The OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index. OECD Trade Policy Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 221. [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane, M.F.; Marelev, D. Do Data Policy Restrictions Inhibit Trade in Services? Rev. World Econ. 2021, 157, 727–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, B.; Gao, J. Digital Trade: An Analytical Framework. Int. Trade Issues 2021, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F.; Fang, R.N.; Wang, D. Topological Structure Characteristics and Influencing Mechanism of the Global Digital Service Trade Network. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2021, 38, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.X.; Dou, K. An Empirical Study on the International Competitiveness of China’s Digital Trade Based on the “Diamond Model”. Soc. Sci. 2019, 3, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguerre, C. Digital Trade in Latin America: Mapping Issues and Approaches. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2019, 21, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpai News. Enhancing Universal Digital Literacy and Skills—A Key Measure to Bridge the Digital Divide. Pengpai News, 12 May 2023.

- Zhan, J.B.; Wang, C. Digital Trade Promotes High-Quality Development of Foreign Trade: The Theoretical Mechanism and Empirical Test—Based on the Mediating Effect of Digital Technology Innovation. Commer. Econ. Res. 2024, 12, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.J.; Ren, Z.L.; Dai, D.D. Domestic–International Dual Circulation, Innovation Capacity, and High-Quality Development of China’s Digital Trade—A Firm-Level Test. Mod. Financ. (Tianjin Univ. Financ. Econ. J.) 2022, 42, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z. The Impact of Innovation-Driven Policies on the International Competitiveness of Digital Trade: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zones. Reform 2024, 3, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.Y. Factors Influencing China’s Manufacturing Exports to ASEAN Under the Digital Economy. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University for Nationalities, Nanning, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.H.B.; Gu, Y.; Gu, J.H. ASEAN Digitalization Construction and FDI Efficiency Analysis. Technol. Econ. Manag. Res. 2021, 5, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Technology acceptance model: TAM. In Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption; Al-Suqri, M.N., Al-Aufi, A.S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 1989; Volume 205, p. 219. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Singapore | Indonesia | Thailand | Malaysia | Vietnam | Philippines | Cambodia | Brunei | Laos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 9951 | 5134 | 6818 | 2372 | 2860 | 3473 | 13 | 64 | 23 |

| 2008 | 9692 | 5133 | 6741 | 5303 | 3199 | 3313 | 39 | 75 | 37 |

| 2009 | 8736 | 4518 | 5857 | 5737 | 2890 | 2997 | 28 | 42 | 18 |

| 2010 | 9773 | 5630 | 1937 | 6383 | 3582 | 3393 | 26 | 0 | 20 |

| 2011 | 9794 | 5830 | 3924 | 6452 | 3560 | 3196 | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| 2012 | 9685 | 0 | 6746 | 6940 | 3805 | 2994 | 53 | 31 | 53 |

| 2013 | 9722 | 7450 | 7404 | 7205 | 3995 | 3285 | 75 | 35 | 70 |

| 2014 | 10,312 | 8023 | 7930 | 7620 | 4447 | 3589 | 67 | 117 | 44 |

| 2015 | 10,814 | 9153 | 8167 | 7727 | 5033 | 3734 | 65 | 0 | 62 |

| 2016 | 10,980 | 9639 | 7820 | 7236 | 5228 | 3419 | 80 | 89 | 63 |

| 2017 | 10,930 | 9303 | 7865 | 7072 | 5382 | 3395 | 55 | 107 | 100 |

| 2018 | 11,845 | 9754 | 8149 | 7295 | 6071 | 4300 | 161 | 121 | 59 |

| 2019 | 14,136 | 11,481 | 8172 | 7551 | 7520 | 4380 | 310 | 141 | 0 |

| 2020 | 13,265 | 8160 | 7525 | 6828 | 7695 | 3993 | 248 | 120 | 0 |

| 2021 | 14,590 | 8800 | 8242 | 7534 | 8534 | 4393 | 0 | 139 | 0 |

| Average | 10,948.33 | 7200.53 | 6886.47 | 6617 | 4920.07 | 3590.27 | 84.2 | 72.07 | 39.47 |

| Ranking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1st tier (>10,000) | 2nd tier (5000–10,000) | 3rd tier (1000–5000) | 4th tier (<1000) | ||||||

| Year | ICT Product Import | ICT Product Export | ICT Service Export | ICT Service Import |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.34 | 0.42 |

| 2008 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.38 | 0.29 |

| 2009 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| 2010 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| 2011 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| 2012 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.26 |

| 2013 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| 2014 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.26 |

| 2015 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| 2016 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| 2017 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.41 | 0.33 |

| 2018 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| 2019 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.23 |

| 2020 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.25 |

| 2021 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.35 |

| Indicator | Abbreviation | Description | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | Digital Trade | igt | Total trade of ICT products and services (imports and exports) | OECD website, Asian Development Bank |

| ist | Total trade of ICT services (imports and exports) | Asian Development Bank | ||

| igs | Total trade of ICT products (imports and exports) | OECD website | ||

| Core Explanatory Variable | Number of Patent Applications | patentnew | Total number of patent applications by residents and non-residents | World Bank |

| Mediating Variable | Degree of Digitization | dig | A digitalization index calculated based on data such as fixed broadband users, mobile cellular users, and internet users in ASEAN countries | United Overseas Bank |

| Moderating Variable | Revealed Comparative Advantage Index | rca | Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index measures the export advantage of a country or region in specific goods or services compared to others | |

| Control Variables | GDP Growth Rate | gdpg | Reflects changes in the economic development level over a certain period and indicates the economic vitality of a country or region | World Bank |

| Foreign Direct Investment | fdi | Refers to economic investments made by foreign enterprises to gain profits locally | World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators | |

| Wage–Output Ratio of the Digital Economy Industry | ictsal | Reflects the ratio between the value created by the digital industry during production and the wages earned by employees, indicating the industry’s cost structure. A higher wage–value ratio implies stronger competitiveness in international markets | Calculated | |

| Government Efficiency | gover | Reflects public perception of the quality of public services, the civil service, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and government credibility | OECD website | |

| Regulatory Quality | regu | Reflects perceptions of the government’s ability to promote the healthy development of the private sector | World Bank | |

| Discourse Power and Accountability | voice | Indicates the extent to which citizens can participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of speech, association, and media | World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators | |

| Political Stability | political | The likelihood of the government being destabilized or overthrown through unconstitutional or violent means, including politically motivated violence and terrorism | ||

| Corruption Level | control | Measures the extent to which public power is used for private gain, including corruption and the capture of the state by elites and private interests |

| Variable | Sample Size | Average | Std. Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_igt | 135 | 59,166.7 | 70,793.67 | 0 | 292,257 |

| log_igs | 135 | 60,755.76 | 71,165.76 | 26.83 | 293,222.3 |

| log_ist | 135 | 1589.06 | 1123.474 | 26.83 | 4160.18 |

| log_patentnew | 127 | 7.343036 | 2.192033 | 2.564949 | 9.588092 |

| log_fdi | 135 | 21.96975 | 3.144499 | 0 | 25.65445 |

| ictsal | 135 | 3.59049 | 1.099222 | 1.528945 | 5.119914 |

| gdpg | 135 | 4.355513 | 3.54322 | −9.518294 | 14.51975 |

| political | 135 | −0.0003056 | 0.8637988 | −1.779236 | 1.599123 |

| control | 135 | −0.1587817 | 0.9922328 | −1.356795 | 2.231618 |

| gover | 135 | 0.325671 | 0.9223399 | −1.00112 | 2.46966 |

| regu | 135 | 0.1702988 | 0.8583541 | −1.186762 | 2.252235 |

| voice | 135 | −0.6848291 | 0.6178046 | −1.815576 | 0.1848712 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_igt | log_igs | log_ist | log_igt | log_igs | log_ist | |

| log_patentnew | 1.2397 *** (0.901) | 0.887 *** (0.073) | 0.374 *** (0.053) | 1.226 *** (0.081) | 1.314 *** (0.408) | 0.344 *** (0.046) |

| political | −0.303 (0.239) | −1.274 *** (0.265) | 0.269 ** (0.134) | |||

| control | −1.166 *** (0.478) | −0.375 (0.565) | −1.125 *** (0.268) | |||

| gover | 0.539 (0.516) | 2.287 *** (0.557) | −0.081 (0.289) | |||

| regu | 1.606 *** (0.528) | −0.244 (0.588) | 0.903 *** (0.296) | |||

| voice | −0.927 *** (0.282) | −0.280 (0.322) | 0.113 (0.158) | |||

| log_fdi | 0.027 (0.034) | 0.155 *** (0.037) | −0.018 (0.019) | |||

| ictsal | 0.072 (0.133) | 0.836 *** (0.136) | 0.379 *** (0.075) | |||

| gdpg | 0.045 (0.029) | 0.031 (0.034) | 0.024 (0.016) | |||

| Constant | 0.093 (0.688) | 3.085 *** (0.565) | 4.248 *** (0.444) | −2.113 *** (0.815) | −6.621 *** (2.752) | 3.386 *** (0.456) |

| Sample Size | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| R2 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Variable | Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) log_igt 1st Step | (2) dig 2nd Step | (3) log_igt 3rd Step | |

| log_patentnew | 0.669 *** (0.257) | 13.899 *** (2.811) | 0.14 * (0.008) |

| dig | 0.669 *** (0.257) | ||

| Constant | 1.549 (1.054) | 12.754 (12.438) | 0.932 (1.027) |

| Observations | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| R2 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.93 |

| Variable | Dependent Variable (igt) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| log_patentnew | 1.302 *** (0.044) | 1.101 *** (0.061) | 1.091 *** (0.064) |

| patrcai | −0.167 *** (0.059) | −0.254 *** (0.048) | −0.248 *** (0.049) |

| rcaict | 1.648 *** (0.499) | 2.630 *** (0.418) | 2.571 *** (0.424) |

| political | −0.600 *** (0.188) | −0.610 *** (0.189) | |

| control | −1.133 *** (0.367) | −1.290 *** (0.373) | |

| gover | 0.241 (0.380) | 0.367 (0.398) | |

| regu | 2.246 *** (0.400) | 2.365 *** (0.413) | |

| voice | −0.405 * (0.233) | −0.439 * (0.33) | |

| ictsal | 0.006 (0.110) | ||

| gdpg | 0.041 ** (0.020) | ||

| Constant | −0.587 * (0.331) | −0.313 (0.506) | −0.539 (0.569) |

| Sample Size | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| R2 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Variable | Replace the Dependent Variable (sergdp) | Core Variable Lags by One Period (l.log_patentnew) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| log_patentnew | 2.348 *** (0.515) | 1.850 *** (0.598) | 1.337 *** (0.505) | |||

| llog_patentnew | 2.045 *** (0.494) | 1.520 *** (0.607) | 1.303 *** (0.512) | |||

| political | 4.143 *** (1.106) | −7.964 *** (1.593) | 3.993 *** (1.086) | −7.724 *** (1.631) | ||

| control | 6.751 *** (1.943) | 7.468 *** (3.196) | 3.523 * (2.017) | 4.353 (3.322) | ||

| gover | −3.931 ** (2.045) | −4.275 (3.387) | −1.850 (1.912) | −3.767 (3.489) | ||

| regu | −1.397 (1.785) | 10.184 *** (3.474) | 0.257 (1.834) | 13.488 *** (3.637) | ||

| voice | −0.104 (1.922) | −5.913 *** (1.890) | 1.119 (1.950) | −6.648 *** (1.864) | ||

| ictsal | 0.343 (0.889) | 0.463 (0.909) | ||||

| gdpg | 0.529 *** (0.175) | 0.581 *** (0.177) | ||||

| Constant | 30.954 *** (4.746) | 37.105 *** (5.570) | 31.446 *** (4.223) | 33.338 *** (4.627) | 38.917 *** (5.472) | 29.696 *** (4.294) |

| Sample Size | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| R2 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Pham, T.D.; Li, R.; Do, T.T. Enhancing the Sustainable Development of the ASEAN’s Digital Trade: The Impact Mechanism of Innovation Capability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041766

Zhang L, Pham TD, Li R, Do TT. Enhancing the Sustainable Development of the ASEAN’s Digital Trade: The Impact Mechanism of Innovation Capability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041766

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, Thi Dam Pham, Rizheng Li, and Thi Thao Do. 2025. "Enhancing the Sustainable Development of the ASEAN’s Digital Trade: The Impact Mechanism of Innovation Capability" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041766

APA StyleZhang, L., Pham, T. D., Li, R., & Do, T. T. (2025). Enhancing the Sustainable Development of the ASEAN’s Digital Trade: The Impact Mechanism of Innovation Capability. Sustainability, 17(4), 1766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041766