1. Introduction

With the growing severity of global climate change, green finance has emerged as a pivotal tool for promoting sustainable development, garnering widespread attention from governments, financial institutions, and international organizations worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As nations strive to meet the targets set by the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), green finance has become a cornerstone of global efforts to combat environmental degradation and facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. By channeling capital toward environmentally friendly projects—such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, and pollution control—green finance not only supports ecological preservation but also fosters economic resilience and innovation.

Globally, initiatives like the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), and the Green Climate Fund underscore the critical role of financial systems in addressing climate challenges. These efforts highlight the increasing recognition that sustainable finance is not merely an environmental imperative but also a financial one as it seeks to align economic growth with long-term ecological stability. However, while the benefits of green finance in driving environmental and economic transformation are well documented, its potential unintended consequences, particularly on corporate financial stability, remain underexplored.

As the world’s largest developing country and a major contributor to global carbon emissions, China has been at the forefront of green finance innovation. In recent years, China has implemented a series of policies and regulatory frameworks to promote green finance, including the establishment of green credit guidelines, green bond standards, and pilot zones for green finance reform. These measures have significantly accelerated the flow of capital toward sustainable projects, positioning China as a global leader in green finance development. Nevertheless, the implementation of these policies may also introduce new risks, particularly for corporations navigating the transition to greener practices. For instance, firms in high-pollution industries or those undergoing green transformations often face heightened financial pressures due to increased compliance costs, technological investments, and regulatory uncertainties [

5,

6].

In recent years, with the deepening of green finance reforms, enterprises, especially those in high-polluting industries and those facing greater financing constraints, have experienced increased financial pressure [

7,

8]. Green finance policies aim to drive these enterprises to undergo green transformation, but due to the multifaceted factors involved in the transformation process, such as technological innovation, capital investment, and market risks, these enterprises may face a higher risk of debt default [

9]. In particular, against the backdrop of financing difficulties and technological uncertainties, some companies may experience exacerbated financial pressure, increasing the likelihood of debt default. Therefore, understanding the impact of green finance policies on corporate debt default risks, especially the heterogeneity across different types of enterprises and regions, is a key part of evaluating the effectiveness of green finance policies.

This study aims to investigate the impact of green finance reform pilot areas on corporate debt default risk, focusing on how green finance policies function across different types of enterprises and regions. By analyzing pollution-intensive enterprises, non-pollution enterprises, and state-owned enterprises, this study reveals the heterogeneous responses of different types of enterprises after policy implementation. Furthermore, through regional classification analysis, the study explores the different impacts of green finance policies on enterprises in Eastern and Central–Western regions, providing more targeted theoretical support for policy formulation.

The primary innovation of this study lies in its focus on the potential financial risks associated with green finance policies, particularly their impact on corporate debt default risks. While the existing literature extensively explores the positive role of green finance in promoting environmental protection, resource efficiency, and low-carbon transition, there is relatively less attention paid to its potential unintended consequences [

10], especially the possible impacts on corporate financial stability. Previous research primarily emphasizes how green finance supports sustainable development by directing capital toward environmentally friendly projects [

11,

12] but largely overlooks the financial pressures that companies, particularly those in high-pollution industries, may face during the transition process.

This study addresses this gap by examining how green finance policies, while driving environmental improvements, may simultaneously increase corporate debt default risks. For instance, companies undergoing green transformation often face significant challenges such as high costs of technological innovation, uncertain market returns, and stringent regulatory requirements [

13], which may exacerbate financial pressures. By shifting the focus from the benefits of green finance to its risks, this study provides a more balanced perspective on the overall impact of these policies, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of their effects on corporate financial health.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents a theoretical analysis;

Section 3 outlines the research methods and data sources;

Section 4 analyzes the specific impact of green finance policies on corporate debt default risks;

Section 5 provides policy recommendations based on the research findings and research prospects.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

The policies in green finance reform pilot areas typically encourage companies to invest in green projects by offering tax incentives, government subsidies, and green bonds [

14,

15]. These green projects usually involve fields such as renewable energy, energy efficiency improvement, carbon reduction, and environmental protection. While these projects have long-term positive impacts in terms of environmental and social benefits, they generally require a longer investment cycle to realize financial returns [

16,

17]. This phenomenon is not unique to China; similar trends have been observed globally. For instance, studies on green finance initiatives in the European Union (EU) and the United States have highlighted the long gestation periods and high upfront costs associated with green projects, which often necessitate substantial debt financing [

18]. Therefore, companies typically need substantial capital investment to support the initiation, development, and implementation of these projects, which leads to a strong demand for debt financing [

19].

However, the funding requirements for green projects are not only large in amount but also involve long-term capital commitments [

19,

20]. When implementing these green projects, companies often face two types of risks: first, technological risks, particularly in areas like green energy technologies and carbon capture, where the maturity and practical application of the technology can be highly uncertain, and second, policy risks, where changes in policies and regulations may affect the return rates of green projects. These risks are not confined to China. For example, international research on green energy projects in Germany and the UK has shown that technological uncertainties and policy shifts can significantly impact project viability and financial returns [

21]. In particular, in cases where policy encouragement and regulatory enforcement are inadequate, the returns on investments may fall short of expectations.

As companies’ debt burdens increase, financial leverage rises, and the pressure to repay debt also grows [

22]. In the face of project return uncertainties and policy changes, companies’ cash flows may fail to generate as expected, which can lead to deteriorating financial conditions [

23]. This pattern is consistent with findings from international studies. For instance, research on green finance in emerging markets, such as India and Brazil, has demonstrated that the high leverage associated with green projects often exacerbates default risks, particularly when policy support is inconsistent [

24]. When a company’s cash flow is unable to meet debt repayment obligations, it may face liquidity problems [

25] and even default. Therefore, the implementation of green finance reform pilot area policies will not only drive companies to increase their debt financing efforts but also increase the risk of debt default. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Green finance reform pilot zone policies will increase the debt default risk of enterprises in pilot zones.

Although the policies in green finance reform pilot areas provide companies with a wide range of green financing products and financial support, in practice, companies often face significant financing constraints [

26]. This is partly due to the long return cycles and high uncertainty within green projects. While green projects have long-term positive environmental effects, their economic benefits tend to be delayed, especially when technological innovation and market application are still immature. As a result, companies find it difficult to quickly realize financial returns from green projects [

27]. For example, studies on green finance in the EU have highlighted similar financing constraints, where the long-term nature of green investments often conflicts with the short-term profit expectations of investors [

28,

29].

Companies typically rely on traditional business models and profit sources to sustain their operations in the short term [

30]. However, the long-term investment returns from green projects often conflict with these short-term profit models. This causes companies to struggle in securing quick capital inflows through green project financing when they face urgent funding needs [

31,

32]. As a result, companies tend to rely more on debt financing to fill the funding gap. However, increased debt financing raises the company’s financial leverage, further increasing debt repayment pressure [

1,

33,

34]. For instance, research on green finance in the United States has shown that companies often resort to debt financing to bridge the gap between long-term green investments and short-term liquidity needs, which in turn heightens default risks [

25].

At the same time, due to the long-term nature and uncertainty of green projects, traditional financing channels and creditors may question the company’s ability to repay its debt, leading to higher financing costs [

35,

36,

37]. Companies may face higher risk premiums during the financing process, exacerbating financing constraints. To cope with these pressures, companies might resort to more debt financing. This financing dilemma is unlikely to be alleviated in the short term, thereby increasing the risk of default [

38]. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H2a: Enterprises in green finance reform pilot zones may experience increased debt default risk, as green finance policies can exacerbate financing constraints by increasing the uncertainty and long-term nature of green project investments.

Companies in green finance reform pilot areas often require substantial capital investment to support green projects, and the capital demands and liquidity issues of these projects pose significant challenges for businesses [

39,

40]. Green projects typically take several years to yield the expected environmental benefits and financial returns, which results in lower liquidity for the stocks associated with these projects. Stock liquidity is generally understood as the ability of investors to quickly buy or sell a company’s assets, and low liquidity means that a company’s stock is not easily traded or [

10] valued in the market, thus affecting the company’s ability to raise funds through equity financing [

40,

41].

The diversity, technological complexity, and regional differences in green projects result in a low level of standardization, which creates significant barriers for investors to understand and assess these projects [

42,

43]. This, in turn, affects the market’s pricing of these companies. In the stock market, a lack of liquidity means that investors are unable to quickly adjust their portfolios, especially when a company faces urgent funding needs. In such cases, shareholder and investor support may not meet expectations. This low liquidity not only limits the company’s ability to raise funds through capital markets but may also make it difficult for the company to resolve funding shortages through equity financing [

44].

Furthermore, low liquidity can lead to a depressed market valuation for the company’s stock, which affects the company’s market confidence [

44,

45]. In such situations, companies rely more on debt financing to meet their funding needs. The increased reliance on debt financing inevitably leads to higher financial leverage, thereby raising the risk of debt default. Due to low stock liquidity, the company’s financing costs rise, which in turn increases the risk of debt default. For example, research on green finance in Scandinavia has shown that low stock liquidity often exacerbates financing challenges, leading to higher default risks for companies engaged in green projects [

10]. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H2b: Enterprises in green finance reform pilot zones may face higher debt default risk, as the low liquidity of stocks associated with green projects can limit their ability to raise funds through equity markets, forcing them to rely more on debt financing.

5. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

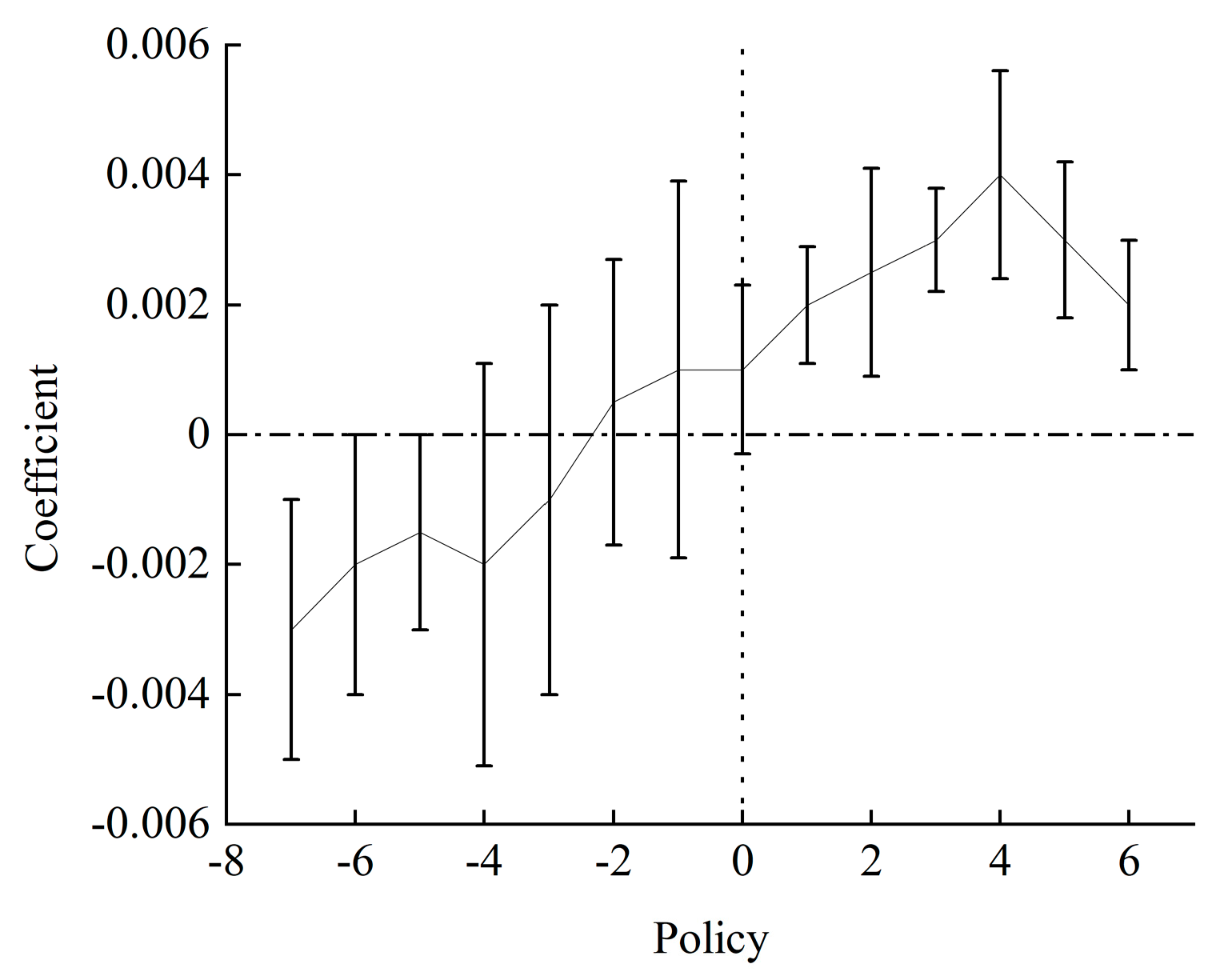

The study presented in this paper shows that green finance reform policies have exacerbated corporate debt default risks to some extent, particularly for polluting firms and those facing greater financing constraints. Polluting firms have experienced increased financing pressures and greater uncertainty regarding technological transformation following policy implementation, leading to a significant rise in their default risk. This can be attributed to several underlying factors. First, polluting firms face substantial costs to meet stricter environmental standards, including investments in cleaner technologies and production processes. These costs can strain their financial resources, especially for firms already operating with limited liquidity. Second, as green finance policies emphasize environmental performance, polluting firms may suffer from reputational damage, which can further restrict their access to financing. Investors and financial institutions may perceive these firms as higher-risk borrowers, leading to higher borrowing costs or even credit rationing. Third, variations in policy enforcement across regions may exacerbate the challenges faced by polluting firms. In regions with stricter enforcement, firms may face more immediate and severe financial pressures, while in regions with more lenient enforcement, the transition may be slower but still fraught with uncertainty.

In contrast, non-polluting and state-owned enterprises are less affected by policies, indicating heterogeneous responses across different types of firms within the green finance reform. Non-polluting firms typically have lower compliance costs and are better positioned to benefit from green finance incentives, such as preferential loans or tax breaks. State-owned enterprises, on the other hand, often have stronger financial backing and greater access to government support, which mitigates the risks associated with the transition to greener practices.

Furthermore, the regional classification analysis revealed the varying impacts of green finance policies across different areas. In the Eastern region, firms face a significantly higher default risk, which may be linked to stricter environmental regulations and increased market competition. The Eastern region, being more economically developed, often implements environmental policies more rigorously, placing additional financial and operational burdens on firms. Additionally, the higher level of market competition in this region may amplify the financial risks for firms undergoing green transformation, as they must balance compliance costs and maintaining competitiveness. Meanwhile, firms in the Central and Western regions are less affected, likely due to smaller firm sizes and lower pressures related to the implementation of green projects. These regions may also benefit from more gradual policy implementation and greater government support aimed at promoting regional economic development.

Based on these findings, this paper offers the following policy recommendations: First, the government should adopt differentiated green finance policies tailored to the characteristics of different types of enterprises and regions, avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach. For polluting firms and those with greater financing constraints, policies should provide targeted financial support, such as green credit lines, low-interest loans, and financing guarantees, to alleviate the financial pressure they face during the transformation process. For example, establishing a dedicated green transition fund could help these firms access the capital needed for technological upgrades and compliance with environmental standards.

Second, for firms in the eastern region with high default risks, it is essential to strengthen financing support for green projects and implement measures to mitigate the financial risks associated with the green transition. Specific tools, such as green bonds or public–private partnerships, could be leveraged to mobilize additional resources for green investments. Additionally, the government could introduce risk-sharing mechanisms, such as credit insurance or loan guarantees, to reduce the financial burden on firms and encourage broader participation in green initiatives.

Lastly, in the Central and Western regions, the promotion of green finance policies should focus on the design of incentive mechanisms to enhance firms’ green financing capacity and promote their green transformation. For instance, the government could offer tax incentives or subsidies for firms that adopt green technologies or achieve specific environmental performance targets. Regional green finance pilot programs could also be established to test and scale innovative financing models tailored to the unique economic and environmental conditions of these regions.