Study on the Influence of the Ecological Environment on the Subjective Well-Being of Farmers Around Nature Reserves: Mediating Effects Based on Environmental Cognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Commentary

2.1. Research on Subjective Well-Being and Its Influencing Factors

2.2. Research on Ecological Environment

2.3. Research on the Impact of Ecological Environment on Subjective Well-Being

2.3.1. Natural Environment and Subjective Well-Being

2.3.2. Social Environment and Subjective Well-Being

3. Theoretical Analysis Framework and Research Methods

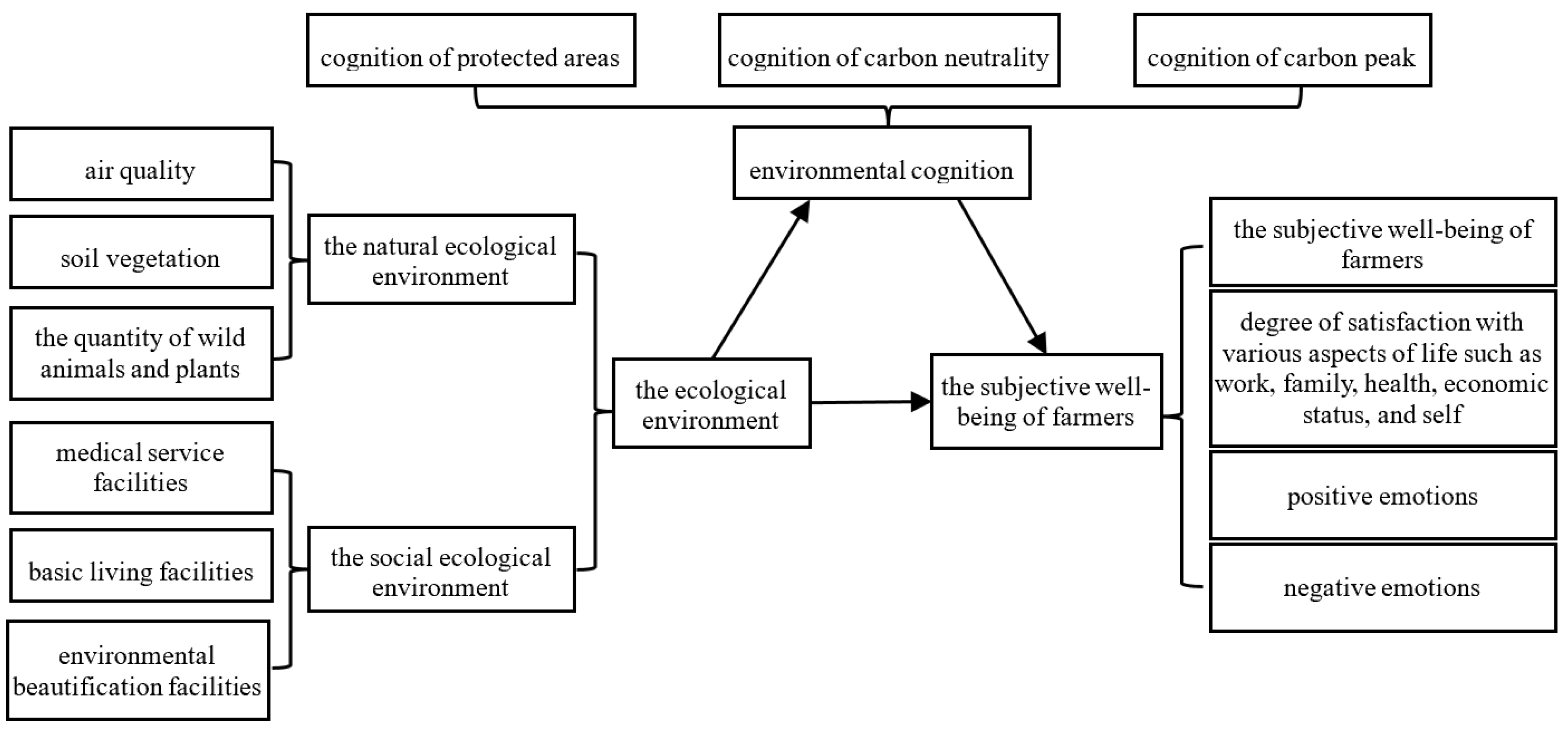

3.1. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Least Squares Regression Model

3.2.2. Mediation Effect Model

4. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Variable Selection

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

5.2. Analysis of Mediating Effects

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4. Robustness Test

- (1)

- Taking the subjective well-being measured by the single scale as the new dependent variable, as the measurement of subjective well-being can be conducted through a single scale or a multidimensional scale. This article uses the subjective well-being measured by a single scale as the dependent variable for robustness testing. The interviewee was asked “Overall, do you think you are happy?” and was assigned a score of 1–5 according to a Likert scale which represented “very unhappy”, “unhappy”, “average”, “happy”, and “very happy”, respectively; the higher the value is, the happier the interviewee is.

- (2)

- We changed the assignment of the new explained variable. The subjective well-being of farmers was judged by their own subjective evaluation. Due to the different definitions of “general” in subjective well-being among farmers, they were unable to make a correct choice between “happy/unhappy” and “general”, resulting in a lower or higher level for the subjective well-being of farmers. This article reassigns values to the subjective well-being of farmers to solve this problem. When farmers answered that they have a low level of happiness, we merged “very unhappy” and “unhappy” into unhappy and assigned them a value of 0, and we similarly merged “average”, “happy”, and “very happy” into happy and assigned farmers who answered in this way a value of 1. When farmers answered that they have a high level of happiness, we merged “very unhappy”, “unhappy”, and “average” into unhappy and assigned them a value of 0, and merged “happy” and “very happy” into happy and assigned them a value of 1.

- (3)

- Next, we transformed the regression model. We took the subjective well-being as a discrete ranking variable and conducted regression on the sample data with an ordered Probit model to test the robustness of the results.

6. Research Conclusions, Discussions, and Policy Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

- (1)

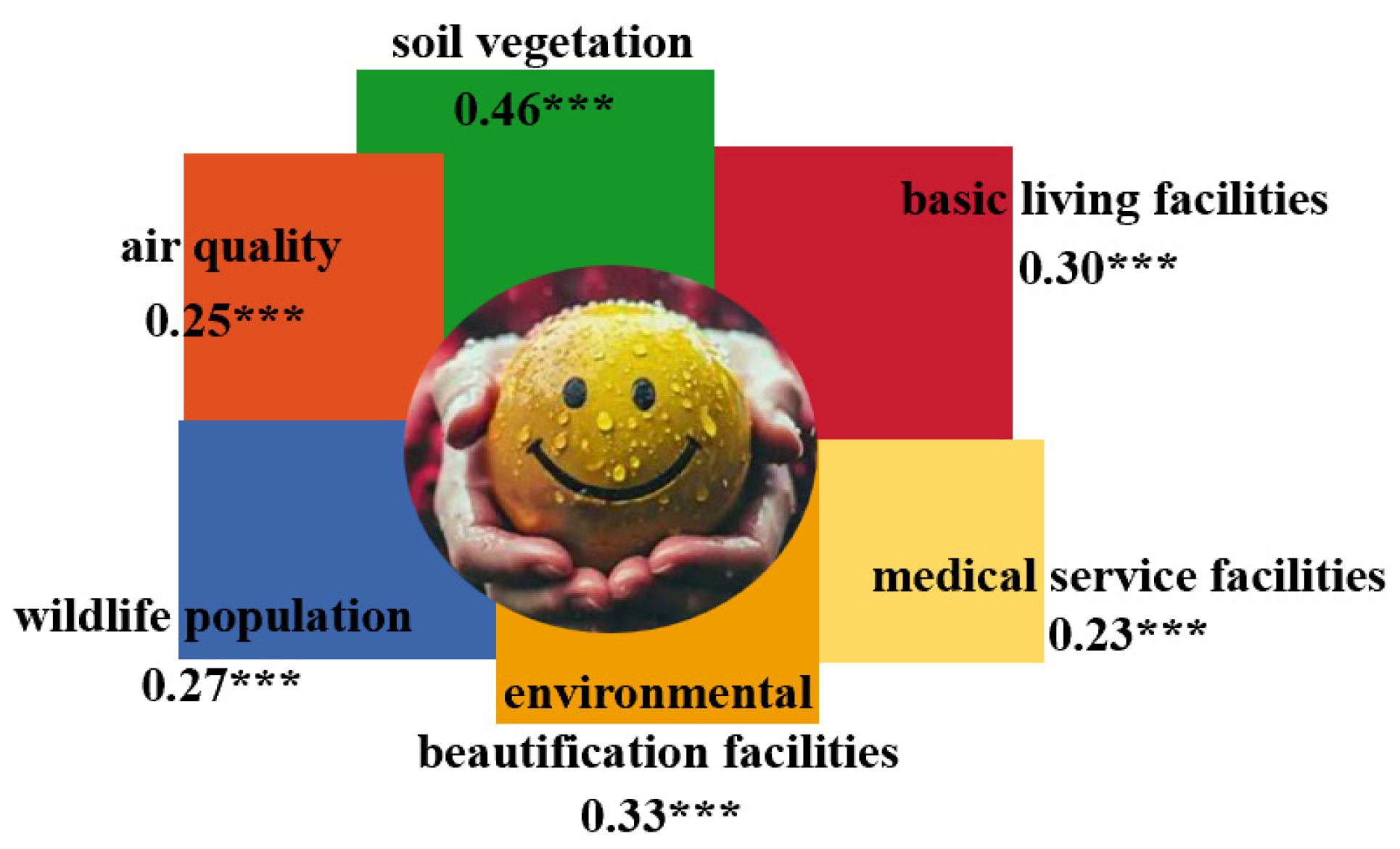

- Both the natural and social environments in the ecological environment have a significant positive impact on the subjective well-being of farmers around nature reserves. For every 1% increase in air quality, soil vegetation, wildlife population, medical service facilities, basic living facilities and environmental beautification facilities, the subjective well-being of farmers increases by 25%, 46%, 27%, 23%, 30%, and 33%, respectively (As shown in Figure 3.).

- (2)

- Subjective well-being is the overall emotional and cognitive evaluation people make of their quality of life. Environmental cognition plays a mediating role between both the natural/social environment and farmers’ subjective well-being.

- (3)

- There are differences in the impact of the ecological environment on the subjective well-being of farmers inside and outside nature reserves. The air quality and soil vegetation in the natural environment have positive impacts on both farmers within and outside nature reserves, which are significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. However, the number of wild animals only has a significant positive impact on farmers outside nature reserves, and has no significant impact on the subjective well-being of farmers within nature reserves. Medical service facilities, basic living facilities, and environmental beautification facilities in the social environment have a significant positive impact on both farmers within and outside nature reserves. The impact of both the natural and social environments in the ecological environment on the subjective well-being of farmers outside nature reserves is higher than that on farmers inside reserves.

6.2. Discussion

6.3. Policy Implications

- (1)

- Increase investment in nature reserves and improve the ecological environment quality of rural areas surrounding reserves. Insufficient funding is an urgent issue that needs to be addressed in the development of nature reserves, which is quite common worldwide. In the context of global environmental governance, it is necessary to further expand funding channels and seek more financial support from international organizations, public welfare funds, etc. to invest in ecological protection work. The subjective well-being of farmers will be improved by improving the quality of their ecological environment.

- (2)

- Strengthen the promotion of ecological environment protection and improve the environmental cognition of farmers around nature reserves. In the context of global ecological environment governance, the government should scientifically formulate environmental protection policies, encourage farmers to adopt measures such as returning straw to the field and applying organic fertilizers to reduce soil greenhouse gas emissions, encourage farmers to use renewable energy to reduce global carbon dioxide emissions, and promote the process of carbon neutrality and carbon peak in rural areas around nature reserves, so as to further improve farmers’ subjective well-being.

- (3)

- Clarify the compensation subject and establish a sound compensation mechanism for wildlife-caused accidents. Establishing nature reserves is the most effective measure to protect biodiversity, and protecting wildlife is also an effective way to maintain ecological balance. With the continuous improvement of the global ecological environment, the number of wild animals continues to increase, and the conflict between farmers and wild animals is becoming increasingly severe. Farmers in nature reserves suffer much more personal and property loss than those outside the reserves. The government should clarify the compensation subject and effectively achieve compensation for households, so as to reduce the loss of farmers around the protected areas and enhance their subjective well-being.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being and personality. In Advanced Personality; Hersen, M., Van, H., Eds.; The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.D.; Gathergood, J. Consumption changes, not income changes, predict changes in subjective well-being. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauseef, S. Can money buy happiness? Subjective wellbeing and its relationship with income, relative income, monetary and non-monetary poverty in Bangladesh. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Zhang, R.; Xie, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cai, W.; Dong, W.; Deng, G. Education and subjective well-being in Chinese rural population: A multi-group structural equation model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orru, K.; Orru, H.; Maasikmets, M.; Hendrikson, R.; Ainsaar, M. Well-being and environmental quality: Does pollution affect life satisfaction? Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, H.E.; Nepal, S.K. Social-ecological wellbeing of communities engaged in ecotourism: Perspectives from Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, Bhutan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1177–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Cai, L. Effects of cultural ecosystem services on visitors’ subjective well-being: Evidences from China’s national park and flower expo. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shuai, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Shuai, J. Topic modelling of ecology, environment and poverty nexus: An integrated framework. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 267, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başar, S.; Tosun, B. Environmental Pollution Index and economic growth: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36870–36879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.N.; Chen, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Mok, T.M. The dynamic relationship between environmental pollution, economic development and public health: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Hu, X. The health impact of environmental pollution. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, C. Strengthening regional cohesion: Collaborative networks and sustainable development in Swiss rural areas. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.C.; Joshi, B. Local and regional institutions and environmental governance in Hindu Kush Himalaya. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 49, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Yu, H. Analysis on the ecosystem service protection effect of national nature reserve in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from weight perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Sun, X. Study on the impact of air pollution control on urban residents’ happiness from microscopic perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, T. How does air quality affect residents’ life satisfaction? Evidence based on multiperiod follow-up survey data of 122 cities in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 61047–61060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M. Heterogeneity in the impact of air pollution on labor mobility: Insights from panel data analysis in China. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, D. Analysis of the impact of social insurance on farmers in China: A study exploring subjective perceptions of well-being and the mechanisms of common prosperity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1004581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattnaik, P. Study of subjective wellbeing of adult population in arsenic contaminated rural areas of west bengal. Pollut. Res. 2020, 39, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Du, G.; Shin, K.J.; Managi, S. Variability in impact of air pollution on subjective well-being. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 183, 175–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wood, S.A.; Lawler, J.J. The relationship between natural environments and subjective well-being as measured by sentiment expressed on Twitter. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, D. Air pollution, environmental protection tax and well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ren, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. The impact of air pollution on individual subjective well-being: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S. The subjective well-being of older adults in Shanghai: The role of residential environment and individual resources. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1692–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, S.J.; Desai, S.A.; Mutsaa, E.; Lottering, R.T. A comparative study of community perceptions regarding the role of roads as a poverty alleviation strategy in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 71, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Lien, C.H.; Wang, T.; Lin, T.W. Impact of social support and reciprocity on consumer well-being in virtual medical communities. INQUIRY: J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2023, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.B.; Kim, C.B.; Ranabhat, C.; Kim, C.S.; Chang, S.J.; Ahn, D.W.; Joo, Y.K. Influence of community satisfaction with individual happiness: Comparative study in semi-urban and rural areas of Tikapur, Nepal. Glob. Health Promot. 2018, 25, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, D.; Zhan, D. How does growing city size affect residents’ happiness in urban China? A case study of the Bohai rim area. Habitat Int. 2020, 97, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, K.; Li, R.L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.J. Air pollution impairs subjective happiness by damaging their health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Perceived residential environment of neighborhood and subjective well-being among the elderly in China: A mediating role of sense of community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. Effect of the ecological environment on the residents’ happiness: The mechanism and an evidence from Zhejiang Province of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, R. Ecologically sustainable development: Origins, implementation and challenges. Desalination 2006, 187, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Ambrose, S.H.; Bassett, T.J.; Bowen, M.L.; Crummey, D.E.; Isaacson, J.S.; Johnson, D.N.; Lamb, P.; Saul, M.; Winter-Nelson, A.E. Meanings of environmental terms. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qi, Z.; Zhu, L. Latitudinal and longitudinal variations in the impact of air pollution on well-being in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 90, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsen, C.N.; Mizuta, K.; Wulfhorst, J.D. Advancing the intersection of soil and well-being systems science. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, P.O.W.; Agyei, F.K. Biodiversity, environmental health and human well-being: Analysis of linkages and pathways. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1085–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, P.; Garg, R.K. A study on farmers’ satisfaction and happiness after the land sale for urban expansion in India. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-García, G.; Buendía-Azorín, J.D.; Sánchez-de-la-Vega, M.D.M. Infrastructure and subjective well-being from a gender perspective. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Kong, X.; Liu, G. Restructuring rural settlements based on subjective well-being (SWB): A case study in Hubei province, central China. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, F. Rural–urban living and level of economic development as factors in subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frager, R.; Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Yin, M.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X. Exploring the influence path of high-rise residential environment on the mental health of the elderly. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.J.N.; Kim, M.J. Green environments and happiness level in housing areas toward a sustainable life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Yu, Y. Relationship between ecosystem services and farmers’ well-being in the Yellow River Wetland Nature Reserve of China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartter, J. Attitudes of rural communities toward wetlands and forest fragments around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2009, 14, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Is environment ‘a city thing’ in China? Rural–urban differences in environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, N. Research on citizen participation in government ecological environment governance based on the research perspective of “dual carbon target”. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 5062620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, K.; Pang, X. Investigation into the Factors Affecting the Green Consumption Behavior of China Rural Residents in the Context of Dual Carbon. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardage, C.; Pluijm, S.M.; Pedersen, N.L.; Deeg, D.J.; Jylhä, M.; Noale, M.; Blumstein, T.; Otero, Á. Self-rated health among older adults: A cross-national comparison. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prus, S.G. Comparing social determinants of self-rated health across the United States and Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, D.; Chen, K. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on urban residents’ consumption behavior of forest food—An empirical study of 6,946 urban residents. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1289504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Chen, J.; Johannesson, M.; Kind, P.; Burström, K. Subjective well-being and its association with subjective health status, age, sex, region, and socio-economic characteristics in a Chinese population study. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 833–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen, T.; Fibæk, M.; Tarp, F.; Tuan, N.D.A. The happy farmer: Self-employment and subjective well-being in rural Vietnam. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1613–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Deller, S. Effect of farm structure on rural community well-being. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Nature Reserve | Position | Village(s) | Sample Size (Units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laotudingzi Nature Reserve | Huanren Manchu Autonomous County/Xinbin County, Benxi City | 9 | 184 |

| Baishilazi Nature Reserve | Kuandian County, Dandong City | 4 | 75 |

| Haitangshan Nature Reserve | Fuxin Mongolian Autonomous County, Fuxin City | 14 | 309 |

| Heshanghatai Nature Reserve | Benxi County, Benxi City | 4 | 76 |

| Sankuaishi Nature Reserve | Fushun County, Fushun City | 8 | 194 |

| Monkey Stone Nature Reserve | Fushun County, Fushun City | 5 | 118 |

| Total | 44 | 956 |

| Variable Type | Variable Description | Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained Variable | Subjective well-being | Life Satisfaction | 1 = very dissatisfied 2 = dissatisfied 3 = average 4 = satisfied 5 = very satisfied | 3.61 | 0.57 |

| Positive Emotions | 1 = Never 2 = Occasionally 3 = Sometimes 4 = Often 5 = Always | 2.93 | 1.04 | ||

| Negative Emotions | 1 = Never 2 = Occasionally 3 = Sometimes 4 = Often 5 = Always | 1.77 | 0.86 | ||

| Explanatory Variable | Natural Environment | Air Quality Situation | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 4.33 | 0.75 |

| Soil and Vegetation Conditions | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 3.89 | 0.98 | ||

| Number of Wild Animals | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 3.89 | 1.05 | ||

| Social Environment | Medical Service Facilities | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 3.54 | 1.17 | |

| Basic Living Facilities | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 3.91 | 1.04 | ||

| Control Variable | Individual Level | Environmental Beautification Facilities | 1 = very poor 2 = poor 3 = average 4 = good 5 = very good | 4.02 | 1.02 |

| Gender | 1 = Male 0 = Female | 0.58 | 0.49 | ||

| Age | Actual age of farmers | 54.75 | 10.62 | ||

| Educational Level | 1 = Never attended school 2 = Primary school 3 = Junior high school 4 = High school/vocational school 5 = Junior College diploma 6 = Undergraduate degree 7 = Graduate degree (including doctoral degree) | 2.90 | 0.78 | ||

| Marital Status | 1 = Married 2 = Unmarried 3 = Divorced 4 = Widowed | 1.15 | 0.60 | ||

| Self-Assessed Health Status | 1 = very good 2 = good 3 = average 4 = not good 5 = very bad | 1.75 | 0.90 | ||

| Medical Insurance | 1 = Yes 0 = No | 0.10 | 0.30 | ||

| Endowment Insurance | 1 = Yes 0 = No | 0.20 | 0.40 | ||

| Household Level | Annual Total Household Income | Annual household income logarithm | 10.89 | 0.88 | |

| Cultivated Area | Family-owned cultivated land area (mu) | 12.21 | 17.13 | ||

| Forest Land Area | Area of family-managed forest land (mu) | 69.95 | 222.99 | ||

| Intermediary Variable | Environmental Cognition | 1 = strongly disagree 2 = disagree 3 = average 4 = agree 5 = strongly agree | 3.30 | 0.67 | |

| Variable | Subjective Well-Being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Air Quality | 0.25 *** | |||||

| (2.66) | ||||||

| Soil Vegetation | 0.46 *** | |||||

| (6.99) | ||||||

| The Quantity of Wild Animals and Plants | 0.27 *** | |||||

| (4.41) | ||||||

| Medical Service Facilities | 0.23 *** | |||||

| (3.97) | ||||||

| Basic Living Facilities | 0.30 *** | |||||

| (4.42) | ||||||

| Environmental Beautification Facilities | 0.33 *** | |||||

| (4.87) | ||||||

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| (0.92) | (0.26) | (0.65) | (1.24) | (0.75) | (1.07) | |

| Age | 0.02 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.03 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.02 *** |

| (2.86) | (3.22) | (3.29) | (2.98) | (3.08) | (2.78) | |

| Education Level | 0.29 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.28 *** |

| (2.95) | (2.97) | (3.28) | (2.63) | (2.65) | (2.86) | |

| Health Status | −0.43 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.43 *** |

| (−5.45) | (−5.49) | (−5.37) | (−5.47) | (−5.54) | (−5.62) | |

| Marital Status | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.21) | (0.24) | (0.23) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.11) | |

| Medical Insurance | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| (1.39) | (1.46) | (1.36) | (1.40) | (1.42) | (1.63) | |

| Pension Insurance | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.32 * | 0.26 |

| (1.48) | (1.28) | (1.44) | (1.51) | (1.86) | (1.51) | |

| LN the Total Annual Household Income | 0.22 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.21 ** | 0.23 *** |

| (2.58) | (2.88) | (2.65) | (2.78) | (2.77) | (2.69) | |

| Cultivated Land Area | 0.01 ** | 0.01 ** | 0.01 ** | 0.01 * | 0.01 ** | 0.01 ** |

| (2.16) | (1.98) | (2.35) | (1.89) | (2.20) | (2.28) | |

| Forest Land Area | −0.00 ** | −0.00 ** | −0.00 ** | −0.00 ** | −0.00 *** | −0.00 *** |

| (−2.56) | (−2.48) | (−2.57) | (−2.50) | (−2.74) | (−2.92) | |

| Constant | −4.42 *** | −5.41 *** | −4.68 *** | −4.32 *** | −4.43 *** | −4.72 *** |

| (−3.48) | (−4.45) | (−3.81) | (−3.52) | (−3.64) | (−3.91) | |

| Sample Size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| F | 10.19 | 16.01 | 11.46 | 12.18 | 11.92 | 12.91 |

| Variable | Subjective Well-Being | Air Quality | Soil Vegetation | The Quantity of Wild Animals and Plants | Medical Service Facilities | Basic Living Facilities | Environmental Beautification Facilities | Environmental Cognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Well-Being | 1 | |||||||

| Air Quality | 0.07 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Soil Vegetation | 0.21 *** | 0.25 *** | 1 | |||||

| The Quantity of Wild Animals and Plants | 0.11 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.24 *** | 1 | ||||

| Medical Service Facilities | 0.13 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.08 ** | 1 | |||

| Basic Living Facilities | 0.15 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.34 *** | 1 | ||

| Environmental Beautification Facilities | 0.15 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.45 *** | 1 | |

| Environmental Cognition | 0.38 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.11 *** | 1 |

| Variable | Subjective Well-Being (1) | Environmental Cognition (2) | Subjective Well-Being (3) | Subjective Well-Being (4) | Environmental Cognition (5) | Subjective Well-Being (6) | Subjective Well-Being (7) | Environmental Cognition (8) | Subjective Well-Being (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Quality | 0.25 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.13 * | ||||||

| (2.66) | (3.87) | (1.40) | |||||||

| Environmental Cognition | 1.06 *** | 1.01 *** | 1.04 *** | ||||||

| (10.94) | (10.67) | (10.72) | |||||||

| Soil Vegetation | 0.46 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.38 *** | ||||||

| (6.99) | (3.20) | (6.03) | |||||||

| The Quantity of Wild Animals and Plants | 0.27 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.19 *** | ||||||

Control Variable | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | (4.41) controlled | (3.79) controlled | (3.20) controlled |

| Constant | −4.42 *** | 1.98 *** | −6.51 *** | −5.41 *** | 2.05 *** | −7.49 *** | −4.68 *** | 2.04 *** | −6.80 *** |

| (−3.48) | (4.95) | (−5.57) | (−4.45) | (5.11) | (−6.52) | (−3.81) | (5.03) | (−5.99) | |

| Sample Size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.22 |

| Variable | Subjective Well-Being | Environmental Cognition | Subjective Well-Being | Subjective Well-Being | Environmental Cognition | Subjective Well-Being | Subjective Well-Being | Environmental Cognition | Subjective Well-Being |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Medical Service Facilities | 0.23 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.16 *** | ||||||

| (3.97) | (3.54) | (2.91) | |||||||

| Environmental Cognition | 1.04 *** | 1.03 *** | 1.03 *** | ||||||

| (10.87) | (10.27) | (10.77) | |||||||

| Basic Living Facilities | 0.30 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.13 ** | ||||||

| (4.42) | (8.30) | (1.98) | |||||||

| Environmental Beautification Facilities | 0.33 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.25 *** | ||||||

| (4.87) | (3.31) | (3.83) | |||||||

| Control Variable | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled |

| Constant | −4.32 *** | 2.14 *** | −6.55 *** | −4.43 *** | 1.90 *** | −6.38 *** | −4.72 *** | 2.09 *** | −6.87 *** |

| (−3.52) | (5.46) | (−5.74) | (−3.64) | (5.05) | (−5.61) | (−3.91) | (5.26) | (−6.14) | |

| Sample Size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.22 |

| Variable | Subjective Well-Being | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Within Nature Reserves | Outside Nature Reserves | ||

| (1) | (2) | ||

| air quality | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** | |

| (2.12) | (2.04) | ||

| natural ecological environment | soil vegetation | 0.47 *** | 0.48 *** |

| (4.94) | (5.20) | ||

| the quantity of wild animals and plants | 0.14 | 0.38 *** | |

| (1.62) | (4.25) | ||

| medical service facilities | 0.14 * | 0.32 *** | |

| (1.73) | (3.95) | ||

| social ecological environment | basic living facilities | 0.21 ** | 0.38 *** |

| (2.32) | (4.20) | ||

| environmental beautification facilities | 0.31 *** | 0.34 *** | |

| (3.30) | (3.89) | ||

| control variable sample size | controlled 402 | controlled 554 | |

| Variable | Single Scale Subjective Well-Being (Oprobit) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| air quality | 0.19 * | |||||

| (1.90) | ||||||

| soil vegetation | 0.18 *** | |||||

| (2.81) | ||||||

| the quantity of wild animals and plants | 0.12 * | |||||

| (1.74) | ||||||

| medical service facilities | 0.19 *** | |||||

| (3.20) | ||||||

| basic living facilities | 0.14 ** | |||||

| (1.96) | ||||||

| environmental beautification facilities | 0.19 *** | |||||

| (2.90) | ||||||

| control variable | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled |

| sample size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Variable | Single Scale Subjective Well-Being (Oprobit) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| air quality | 0.15 ** | |||||

| (2.28) | ||||||

| soil vegetation | 0.22 *** | |||||

| (4.64) | ||||||

| the quantity of wild animals and plants | 0.17 *** | |||||

| (3.77) | ||||||

| medical service facilities | 0.17 *** | |||||

| (4.21) | ||||||

| basic living facilities | 0.15 *** | |||||

| (3.30) | ||||||

| environmental beautification facilities | 0.22 *** | |||||

| (4.85) | ||||||

| control variable | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled | controlled |

| sample size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, K.; Cao, B.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y.; He, D. Study on the Influence of the Ecological Environment on the Subjective Well-Being of Farmers Around Nature Reserves: Mediating Effects Based on Environmental Cognition. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041546

Chen K, Cao B, Pan X, Wang Y, He D. Study on the Influence of the Ecological Environment on the Subjective Well-Being of Farmers Around Nature Reserves: Mediating Effects Based on Environmental Cognition. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041546

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ke, Boyang Cao, Xinning Pan, Yang Wang, and Dan He. 2025. "Study on the Influence of the Ecological Environment on the Subjective Well-Being of Farmers Around Nature Reserves: Mediating Effects Based on Environmental Cognition" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041546

APA StyleChen, K., Cao, B., Pan, X., Wang, Y., & He, D. (2025). Study on the Influence of the Ecological Environment on the Subjective Well-Being of Farmers Around Nature Reserves: Mediating Effects Based on Environmental Cognition. Sustainability, 17(4), 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041546