Abstract

Urban livability is becoming an increasingly significant concept in the field of urban planning and design, especially in rapidly urbanizing mid-sized cities of the Global South, where unplanned growth raises concerns about the living condition of city dwellers. With a focus on Khulna City, Bangladesh, this study aims to improve the understanding of how subjective perceptions and objective assessments of urban livability can coexist and foster the effective planning and design of urban environments, in line with broader planning principles. By integrating local community input with expert evaluations and socio-technical analysis at the fine geographic granularity of urban districts, this study reveals a strong alignment between people’s lived experiences and empirical geographic data, but also significant discrepancies. It highlights the importance of inclusive urban planning that considers both human experiences and environmental factors, stressing the need for flexible planning tools that reflect the unique social and cultural contexts of mid-sized cities in addition to objective assessments. The findings underscore the importance of comprehending the factors that influence urban livability for promoting sustainable urban growth and adopting practical land-use plans. Moreover, this study offers valuable guidance for urban planners and policymakers in designing inclusive, accessible, and environmentally sustainable cities, tailored to the socio-economic realities of fast-growing urban areas.

1. Introduction

Urban livability has emerged as a crucial concept in the fields of urban studies, planning, and development, particularly in the context of mid-sized cities in the Global South [1,2,3]. As these cities face fast-paced urbanization, concerns about equitable and sustainable livability have gained prominence [4,5]. Urban planning in mid-sized cities of the Global South routinely presents unique challenges and opportunities owing to their rapid growth and unplanned physical development [3,6]. The present study aims to critically examine the spatial dynamics of urban livability empirically by assessing both subjective perceptions and objective indicators, a dual approach that acknowledges the complex and interrelated factors shaping urban environments. With increasing urbanization in mid-sized cities of the Global South, inclusive urban planning is crucial as it involves engaging local communities in shaping their environments, understanding their unique needs, and addressing contextual factors such as locational attributes and environmental conditions. Following this, there are two main objectives this study aims to accomplish. First, it examines the spatial dynamics of urban livability within the setting of Khulna City, Bangladesh, to enhance knowledge about the level of urban livability with the depth of nuances conducive to the effective planning and design of urban environments. Second, it covers a significant research gap by seeking to determine the degree of concordance between the objective geographical livability ratings of neighborhoods and the subjective opinions of city dwellers and to highlight circumstances conducive to discrepancies. In this endeavor, this research espouses a broad community perspective, underscoring the vital role that both experts’ opinions and local residents’ personal insights play in urban planning and design. This lens brings into focus the critical role of local communities besides experts in visioning and shaping the urban environment, as part of a broader commitment to plan and design more livable and more sustainable cities. This study underlines the need to adequately represent the variety of urban experiences and perspectives.

In recent years, the notion of “urban livability” has gained significant attention, leading to the emergence of research on the evolving development patterns in rapidly growing urban areas [7,8]. It has acquired various meanings, encompassing choices individuals make regarding their residential preferences, as well as the notion of preparing urban areas for better living conditions [9,10,11]. A livable urban setting refers to a location where the physical infrastructure and constructed surroundings are intentionally created to improve residents’ living conditions by satisfying their fundamental requirements. According to this viewpoint, livability may be defined as the degree to which locals engage with their living environment [12,13]. Due to its complexity and variety, the concept of livability lacks a precise or universally accepted definition [14,15]. Since “livability” is a relative concept, its significance may vary depending on the context of time and culture. The specific definition of livability depends on the context, chronology, and evaluation objective, as well as the value structure of the observer. Hence, there is no agreed-upon description of what makes something livable as its outcome. This would typically include a number of dimensions and several criteria and sub-criteria [16].

Over the last century, urbanization has accelerated significantly in most countries. Not only has the rate of change in the geographic extent of cities soared [17,18], but urban areas are also expanding twice as quickly as their population [19,20], and by 2050, urban areas are expected to accommodate approximately 68% of the world population [3]. On the one hand, this expansion of urban areas has resulted in noticeable changes to urban landscapes; experts have noted that uncontrolled expansion and inadequate planning have a significant impact on the life expectancy of residents, on the other hand [6,21,22,23]. Also, the lack of proper planning for emerging mid-size cities in developing countries in particular is hampering the living conditions of city dwellers [5,24]. The haphazard growth of cities in developing countries like India, Bangladesh, and others has resulted in a range of negative consequences [5,25] like traffic congestion [26], environmental pollution [27,28,29], and increasing pressure on urban ecosystems [30], among others. In these circumstances, researchers and policymakers have made strides to enhance the condition of urban life [31,32]. Although the idea of a livable city was first advanced to draw and retain multinational firms, it has now evolved into a significant driver of the government’s adoption of sustainable urban development policies [33]. This brings into focus the growing interest for effective strategies to oversee sustainable urban development [34,35,36] and sustainable urban land-use policies to ensure the future well-being of city dwellers [37]. Therefore, determining the standing of urban livability is fundamental to guiding urban governments in addressing the adverse consequences of unplanned development and in fostering sustainable urban growth.

Livability assessment has gained importance as a necessity for sustainable and livable urban development in developing countries [31,38,39]. Tracking urban livability in cities supports efforts to mitigate the detrimental consequences of future urban settlement development [32,40,41]. In this context, urban planners and other practitioners of urban science pay close attention to urban livability as a balanced and harmonious approach to city development [42,43], and strikingly so in developing nations [8,44]. Many Chinese cities have already started to give heed to this concept and to incorporate it as one of the objectives for long-term sustainable urban development [8,39,45]. Also, the Indian government has recently made the decision to implement an urban livability index based on a variety of variables, including the population, basic infrastructure, historic value, heritage preservation, tourism, crime rate, and public transit system [4]. Recommended by various organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), this assessment system uses a four-dimensional framework that can be applied to evaluate the livability potential of any city [7]. Based on this evaluation approach, this study examines the spatial dynamics of livability in Khulna City, Bangladesh, by conducting an explicitly spatial fine-grain analysis that uses the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) methodology grounded in expert opinions. A suite of variables has been selected by experts to measure livability, which encompasses the dimensions of livability assessment recommended by the WHO. Concurrently, we conducted a qualitative survey of city dwellers based on their lived experiences that permits triangulation to assess how closely the objective geographical livability aligns with the subjective perceptions of city dwellers. Thus, this twofold approach provides valuable insights into how residents perceive a place as more livable and underscores the role of bottom-up visions that should frame future urban design and developments.

Despite growing interest in urban livability assessment, existing research predominantly focuses on large cities or megacities [46,47], often overlooking mid-sized cities in the Global South that are often experiencing rapid, unplanned urban growth [25]. Additionally, most studies either rely on subjective perceptions of livability following social statistics or surveys at low spatial granularity [32,48], overlooking fine-grained geographic information and the sensitivity of community-specific factors, which points to another critical research gap [3,7]. Indeed, relying solely on subjective measures may not provide urban planners with the precise findings needed for effective planning, given the substantial needs of fast-growing Global South cities. While few studies have combined subjective perception along with geographic data at the community level [49], extending this approach for entire cities remains understudied, especially in developing countries with unplanned urban growth. Previous studies rarely sought to integrate both perspectives systematically; therefore, a significant research gap exists in understanding how subjective experiences and objective assessments can complement each other to inform inclusive urban planning in mid-sized cities facing distinct socio-environmental challenges.

By deeply comprehending urban livability and its application in mid-size cities, this study offers significant contributions to sustainable urban planning and design in the Global South. Unlike previous studies that predominantly focus on large cities, this research triangulates subjective perceptions of livability with objective indicators through fine-grained geospatial analysis using the AHP. This dual-method approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of urban livability by combining expert insights with local community engagement. This integration is crucial for supporting sustainable land-use policies and motivating governments to adopt sustainable urban development strategies that mitigate the negative impacts of unplanned development on urban settlements [32,33,45]. Furthermore, by highlighting the coexistence of subjective perceptions and objective livability indicators, this research acknowledges intrinsic value along with actionable insights for urban planners to develop inclusive and sustainable urban environments. For cities across the Global South, this study also underscores the importance for land-use strategies that prioritize proximity to services and amenities, ensuring that urban planning is both socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable. By offering a replicable framework for policymakers, this research serves as a potential model for addressing the unique needs of mid-sized cities, ensuring socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable urban development. Moreover, by advocating for inclusive and planned urban development to city development authorities, this study provides a strategic model to manage and control future development in a planned manner for achieving UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) [46].

2. Theoretical Perspectives on Livability and Urban Planning

Urban livability is a multidimensional concept that reflects the interplay between the built and natural environments and their capacity to enhance residents’ well-being and living satisfaction in a particular place. This study adopts a robust theoretical framework to analyze urban livability, with a particular focus on the unique challenges faced by mid-sized cities experiencing rapid, unplanned growth. Understanding urban livability is essential for designing cities that address immediate human needs while supporting long-term sustainability [4,5,11].

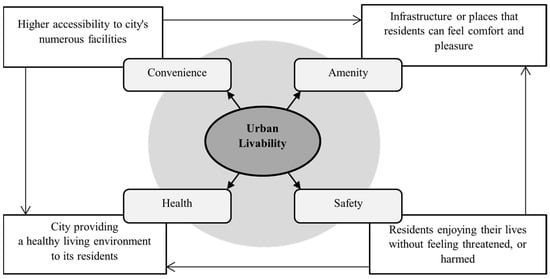

The conceptual foundation of urban livability is built on the four dimensions featured by the World Health Organization (WHO): convenience, amenity, health, and safety [5,7]. Convenience highlights the importance of higher accessibility to a city’s numerous facilities, ensuring ease of use and availability for residents. Building on this, amenity focuses on the presence of infrastructure and places that provide comfort and pleasure, contributing to overall satisfaction with the urban environment. Complementing these, health emphasizes creating a living environment that actively supports physical and mental well-being, addressing fundamental needs for clean and healthy surroundings. Finally, safety ensures that residents can enjoy their lives without feeling threatened or harmed, fostering a sense of security and stability in their communities. Together, these interconnected dimensions provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and assessing urban livability (Figure 1), helping cities better meet the needs of their inhabitants [7,11,41].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of urban livability (adopted and modified from [5,7,41]).

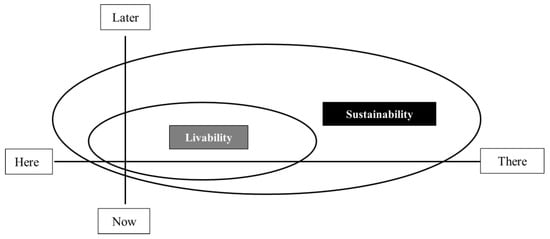

Urban livability is deeply intertwined with sustainability, though the two concepts differ in emphasis. While sustainability focuses on preserving resources for future generations (“there and later”), livability addresses immediate, localized experiences that enhance residents’ quality of life (“here and now”) (Figure 2) [14,15].

Figure 2.

‘Livability’ is a subset of ‘Sustainability’ (adopted and modified from [14,15]).

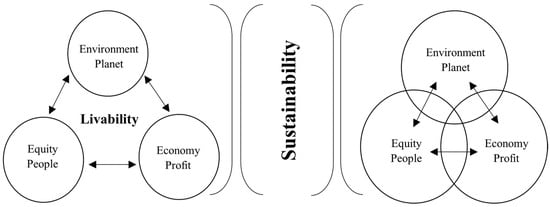

This dynamic relationship positions livability as a subset of sustainability, integrating social, economic, and environmental goals. Livability’s relationship with sustainability can also be viewed through the lens of the “triple-bottom-line” framework, emphasizing equity, economy, and environment (Figure 3). While sustainability often prioritizes environmental preservation, livability brings a sharper focus to social equity and human-centered experiences. This nuanced interplay highlights the complementary roles of livability and sustainability in fostering inclusive urban growth and environmental responsibility [17,18,21,25].

Figure 3.

Livability acts as an integral part of sustainability (adopted and modified from [17,18,21,25]).

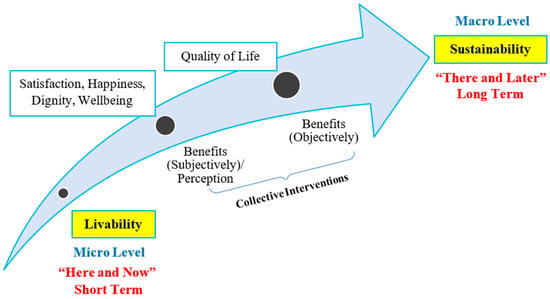

By embedding livability within the sustainability agenda, cities can address short-term challenges while fostering long-term development goals. This connection is particularly significant for mid-sized cities in the Global South, where unplanned urbanization creates unique socio-economic and environmental pressures (Figure 4). To address these challenges, this study draws on urban planning frameworks that expand on these foundational concepts. The Compact City Model advocates for high-density, mixed-use development and efficient public transport systems, minimizing urban sprawl and enhancing walkability [5,7,21]. Similarly, New Urbanism emphasizes human-scale design, vibrant public spaces, and socially cohesive neighborhoods [22,31,32]. Both frameworks align with the livability dimensions of convenience and amenity, offering practical strategies to improve accessibility and urban comfort in rapidly growing cities like Khulna. The Healthy Cities Framework, developed by the WHO, complements these approaches by focusing on urban environments that promote physical and mental well-being [7,37,38]. Prioritizing clean air, green spaces, and sanitation, this framework directly aligns with the health dimension of livability. Addressing environmental challenges such as pollution and inadequate infrastructure in Khulna is critical for improving residents’ quality of life and fostering a livable urban environment.

Figure 4.

Livability as a crucial component of long-term sustainability (adopted and modified from [5,7,25]).

Another key perspective is provided by Resilience and Adaptive Urban Planning, which emphasizes the need for cities to remain functional and inclusive amid rapid urbanization, climate change, and socio-economic pressures [32,33,37]. Resilience frameworks encourage flexibility and preparedness, ensuring that cities can adapt to future uncertainties while maintaining livability. For Khulna, integrating resilience into urban planning is essential for creating stable, adaptable environments. Equity is a central consideration in urban livability, as highlighted by theories of spatial justice and the “just city” framework. Equitable urban planning ensures that all residents, especially marginalized populations, have fair access to services and opportunities. Livability factors, such as accessibility, social cohesion, and environmental quality, directly contribute to improving quality of life for all. These relationships highlight how livability factors translate into tangible benefits for individuals and communities.

This study also draws inspiration from Jane Jacobs’s principles, particularly her emphasis on community-driven design, diversity, and vibrant public spaces. The duality effect strongly aligns with Jacob’s foundational principles of local community engagement, which emphasize the importance of creating vibrant, diverse, and people-centered urban environments [5,7,50] by integrating the perspectives of local citizens into the planning process. Her advocacy for mixed-use neighborhoods and active public spaces remains a cornerstone of modern livability theory and directly informs this study’s emphasis on community perceptions, highlighting the value of local insights in planning sustainable and livable cities. Additionally, this study draws on the Compact City Model, which underpins the contemporary 15 min city concept by emphasizing proximity, accessibility, and walkability as key factors in improving urban livability [6,7,51,52]. For cities across the Global South, this study also underscores the importance of land-use strategies that prioritize proximity to services and amenities, ensuring that urban planning is both socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable. This model, which emphasizes accessibility and proximity, offers actionable solutions for cities like Khulna, where unplanned growth has strained transport networks and reduced accessibility. By promoting localized urban development, the 15 min city concept aligns with both livability and sustainability goals.

By situating urban livability within these theoretical frameworks, this study bridges critical gaps in the literature. The dual-method approach, which combines subjective perceptions with objective indicators, offers actionable insights for policymakers to design inclusive, equitable, and sustainable urban environments. This integrated perspective contributes to advancing sustainable urban development practices tailored to the unique challenges of the Global South [30,53,54].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

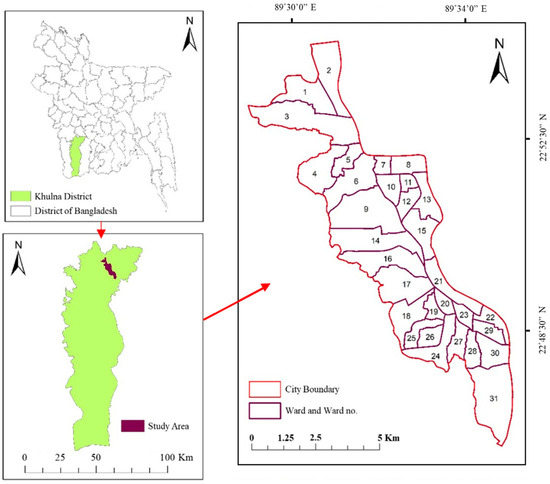

Khulna City in Bangladesh has been chosen as the study area (Figure 5) because of its relevance in representing the challenges and future growth potential that mid-sized cities in the Global South have and for undergoing chaotic urban expansion where rapid population growth and insufficient planning have led to significant urban issues [26,27,28,29]. It has a geographic area of 51 km2 with a population close to 0.6 million [29]. The land-use pattern of Khulna City has evident spatial differentiation marked by a highly heterogeneous living environment across 31 municipal wards [27]. Over the past few decades, Khulna has experienced significant population growth, leading to increased pressure on infrastructure, housing, and public services. Moreover, it faces socio-economic disparities, environmental degradation, and inadequate urban planning challenges that are common to many mid-sized cities in developing countries [27,55]. The scattered growth of cities such as Khulna City affects the overall quality of life of the residents and degrades the urban ecology of the area [30]. The city is also gradually suffering from a series of urban problems, including traffic congestion [26], environmental pollution [27,28,29], and increasing pressure on its infrastructure. These characteristics make Khulna an ideal microcosm for studying urban livability in the context of mid-sized cities with similar urban growth dynamics. By focusing on Khulna, this study provides insights that are broadly applicable to other mid-sized cities in the Global South undergoing similar transformations.

Figure 5.

Map of study area.

3.2. Overview of Research Framework

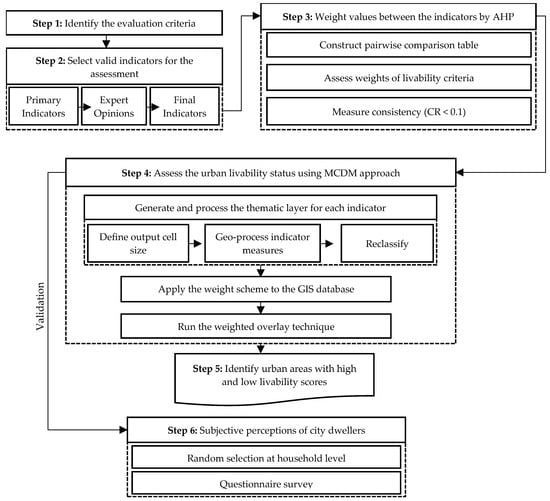

A schematic overview of the methodology to study urban livability in Khulna City is presented in Figure 6. In the first step, several criteria for urban livability were screened out from the literature. Indicators were initially shortlisted through a comprehensive review of studies on urban livability, focusing on their relevance to the four core dimensions (convenience, amenity, health, and safety) and their applicability in the context of mid-sized cities like Khulna. The selection process emphasized indicators commonly used in global studies and aligned with the challenges and priorities of urban planning in the Global South. From the list of indicators, a total of 22 indicators were identified based on expert opinions for the livability assessment of Khulna City. These experts, who are directly involved in Khulna’s urban development, validated the relevance of each indicator, ensuring they capture the local complexities of livability. After finalizing the assessment criteria, the next step involved the implementation of the AHP to assess the weight of every single indicator. Next, an urban livability map was produced following the multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) approach applied to multisource data layers in a geospatial platform. Finally, subjective perceptions on livability were collected from a random sample of city dwellers across locations within the city.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of research.

3.3. Dimensions, Indicators, and Datasets

Livability is a complex concept that includes different aspects of how good it is to live in a place. Researchers have looked at these aspects in slightly different ways in different studies. Relevant articles have been reviewed to understand appropriate data requirements and then identify reliable sources [3,6,7,39,56,57]. As already indicated, the WHO came up with a way to think about livability that embodies four major dimensions. They said it is about how easy things are, how nice the place is, how healthy it is, and how safe it is [3,7]. In our research, we want to measure livability and its variability inside the city and also to consider what people think about it. So, we are using the same four aspects that the WHO suggested: convenience, amenity, health, and safety. For this study, a total of 22 indicators were selected to align with the four dimensions of livability (convenience, amenity, health, and safety) as defined by the WHO framework. Each indicator was chosen based on its relevance to the local context of Khulna City, its ability to represent a specific livability dimension, and its feasibility for geospatial analysis. Additionally, expert consultations were conducted to ensure the chosen indicators accurately reflect the unique socio-environmental and infrastructural conditions of Khulna. These consultations helped refine the indicators by eliminating redundant or less applicable ones and prioritizing those that are most impactful in the study area. See Table 1 for a synopsis.

Table 1.

Dimensions, indicators, relevant literature, and data sources.

In the interest of consistency of the analysis and to enable the calculation of weighted scores of livability for specific geographical locations within the study area, all 22 indicators have been computed for the same set of geographic locations, taken to be the geometric centers of 15 m × 15 m grid cells. Data for this study have been gathered from a diverse array of sources to ensure a robust and comprehensive dataset. All data are compiled from secondary sources (Table 1) in raster data format. These sources encompass satellite imagery, such as MODIS-A2, MODIS-Q1, Landsat 8, Sentinel-2, and Sentinel-5P, which has been processed through the Google Earth Engine Platform. Additionally, we have obtained pertinent data in vector format from local organizations, including local government entities, e.g., Khulna Development Authority (KDA), and selected published documents. Also, whenever possible, point data collected through field surveys and via Google Earth Pro have been integrated to produce a current dataset as of 2022. For the effective visualization, processing, and analysis of the data, we have employed geospatial techniques, resulting in a comprehensive and informative map of livability for our study area.

The processing of satellite imagery has primarily involved classification tasks following well-established procedures used in other studies (see references cited in Table 1). The drinking water quality indicator has been computed from original point data [59]; these data have been interpolated through an IDW process in ArcGIS and finally translated to a 5-class ordinal index based on equal intervals. Distance indicators measure the straight-line distance from each grid cell centroid to the closest feature in its class. This processing was performed in ArcGIS.

3.4. Criteria Weighing Through Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Technique

The AHP is regarded as a powerful deterministic method for weighing and ranking criteria based on expert opinions. The AHP gained wide application in various domains such as site selection, suitability analysis, regional planning, and landslide susceptibility analysis [60,61]. It accepts and weighs the opinions of experts for multi-criteria decision making. It uses pairwise comparisons to measure the relative importance of the criteria in each level and/or calculate the alternatives in order to prioritize options at the lowest level of the hierarchy [62,63,64,65,66].

In this study, the AHP method serves to weigh and rank the factors of urban livability, based on the opinions of five local experts who are directly connected to the core urban planning and development of Khulna City. The panel comprised key professionals, including the Chief Planning Officer of the Khulna City Corporation and Senior Urban Planner of the Khulna Development Authority alongside the project lead of the Healthy City initiative by the WHO. Their expertise was complemented by two senior academics specializing in urban planning, who actively contribute to city development projects. This carefully selected panel ensured that both practical and academic perspectives were integrated, offering a comprehensive understanding of the city’s livability dynamics.

Although the expert panel size was limited to five, steps were taken to mitigate potential biases and ensure representativeness. First, these experts were selected based on their direct involvement with Khulna’s urban development, ensuring their relevance and knowledge of the city’s context. Second, individual judgments were pooled by averaging their pairwise comparison scores, reducing the influence of any single expert’s subjective preferences. Third, the consistency ratio (CR) was calculated for each expert’s judgments to ensure logical coherence, and only responses with a CR below 0.10 were included in the analysis. Finally, the aggregated AHP results were cross-validated against secondary data and reviewed with broader stakeholder feedback to confirm the reliability of the findings.

In this process, we have followed a sequence of five consecutive steps. Initially, a pairwise comparison table was constructed for each dimension based on the assessments of each expert, which were scored on a nine-point Likert scale [64]. Here, the score of 1 refers to equal importance between two compared criteria, while the score 9 indicates an extreme importance of one criterion over another. Second, the scores of experts were averaged into a set of pooled pairwise comparison tables. Third, these pooled tables were converted to square comparison matrices. Fourth, the marginal total within each column of the pairwise comparison matrices was calculated, and subsequently, each value in a column was divided by the marginal total of that particular column, yielding a normalized matrix:

where mij refers to the unnormalized value in the i-th row and j-th column and n represents the number of influential parameters in the pairwise comparison matrix. Following normalization, the sum of entries in each column in the matrix equals 1. Lastly, the internal consistency of expert opinions was assessed using the consistency ratio (CR), as calculated by Equations (2) and (3).

Here, λmax represents the largest eigenvalue of the normalized pairwise comparison matrix, and RI is the random consistency index [67], a predefined constant based on the size of the assessment parameters (N). A CR value exceeding 0.10 indicates inconsistency in the comparison matrix, with the implication that the result is unreliable. Hence, the pairwise comparison process needs to be repeated until achieving acceptable consistency below 0.1 (CR < 0.1). Pooled pairwise comparison tables and matrices are shown in Appendix B.

3.5. Urban Livability Assessment and Map Generation

The 22 indicators listed in Table 1 were processed in several steps to generate Khulna City’s livability map. We started with transforming the disparate measurement scales of the indicators to a consistent 5-point scale linked to the spatial thematic layer (Appendix Table A1). As indicated earlier, to ensure uniformity in spatial data resolutions, we set the spatial resolution of the output to 15 m × 15 m. The processing and preparation of these spatial criteria layers were accomplished using ArcGIS 10.8 software.

After finalizing the spatial criteria layers and calculating their weights with the AHP method, we proceeded to generate digital maps of the dimensions in a common georeferencing system. Subsequently, these spatial thematic layers were merged through cartographic modeling [68] using a weighted overlay operation. To conclude, we classified the resulting map into five distinct ordinal categories of livability status (Very Low, Low, Medium, High, and Very High) for Khulna City, based on equal intervals.

3.6. Direct Insights of City Dwellers on Urban Livability

To gain insights into people’s understanding of urban livability as mediated by the experiences of their daily lives, a semi-structured survey instrument was developed. The objective of this survey was to assemble primary data to gauge the perspective of local residents on better living conditions that they experience and to probe their assessment of desirable locales across Khulna City. The goal was to draft an unfiltered image of livability experiences across Khulna and explore the degree of correspondence with the objective assessment findings of the AHP and MCDM via triangulation.

A sample size of 100 respondents was determined based on logistical considerations and the need for a manageable yet sufficiently diverse dataset to capture a range of perspectives across the city. Respondents were selected using random sampling at the household level across various locations within the city to avoid selection bias and ensure diversity. This diverse cross-section of respondents provides a comprehensive and representative understanding about their subjective views on the city’s livability. To ensure representativeness, sampling locations were distributed to cover neighborhoods from all administrative zones within Khulna City, capturing a mix of socio-economic and demographic profiles.

During the survey, respondents were asked to express their opinions through scoring of the 22 studied indicators that would reveal the degree of concern they have regarding a more livable setting. A 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ’Not Important’ to ’Extremely Important’, was used for scoring these indicators to quantify respondents’ perceptions. In addition, respondents were asked to identify top three Khulna City locations that they consider most livable. Then, they were encouraged to provide detailed reasons behind their choices to rank them in the top three. Moreover, respondents who were not currently residing in any of those places were again asked to share the reasons. This provides valuable insights into the dynamics of urban livability in the city. The survey instrument included a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. A pilot study with 10 participants was conducted to refine the survey for clarity and relevance, incorporating feedback into the final design. To minimize response bias, questions were neutrally phrased, and respondents were assured of complete anonymity. Surveys were conducted in person to ensure consistency in data collection. Sampling locations covered neighborhoods across all administrative zones of Khulna City, ensuring representation of diverse socio-economic and demographic profiles. After data collection, quantitative responses were aggregated and analyzed to identify trends, while qualitative responses were coded thematically to uncover deeper insights. This multi-faceted approach allowed for a comprehensive understanding of urban livability dynamics from the perspectives of city dwellers.

4. Results

4.1. Objective Livability Assessment

4.1.1. Priorities in Urban Livability

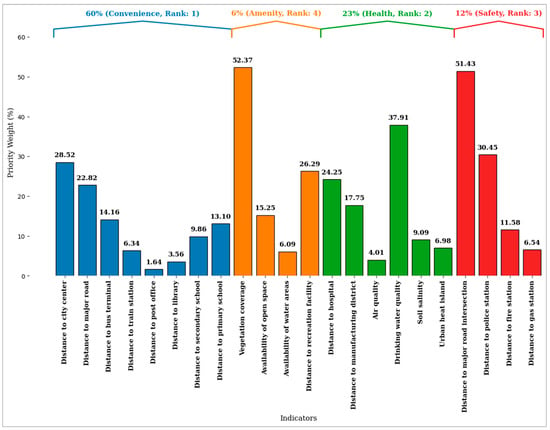

The consensus prioritization achieved through the AHP exercise indicates that urban convenience is the most important dimension (60%), followed by health considerations (23%), safety (12%), and finally amenities (6%) (Figure 7). The contribution towards each dimension of livability is also found to be quite focused on a small number of indicators: only 8 of 22 indicators have a priority score over 20%. Specifically, distance to the city center and to a major road are key determinants of convenience (51% taken together), drinking water quality and distance to a hospital determine health quality (62%), distance to a major road intersection and to a police station identify safe places (82%), and vegetation cover and distance to a recreational facility are the foremost amenities (78%). Each of the four dimensions is further discussed hereunder. Numerical scores are reported in Table A2.

Figure 7.

Prioritization rank of dimensions and indicators.

4.1.2. Convenience Dimension

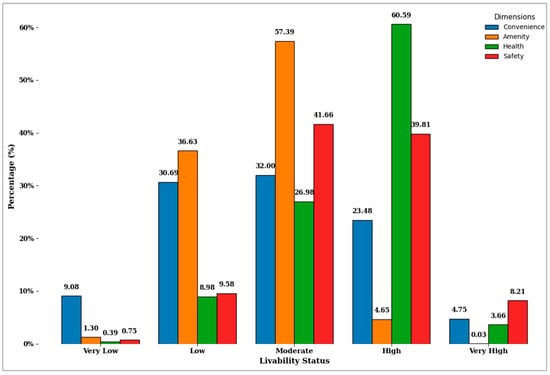

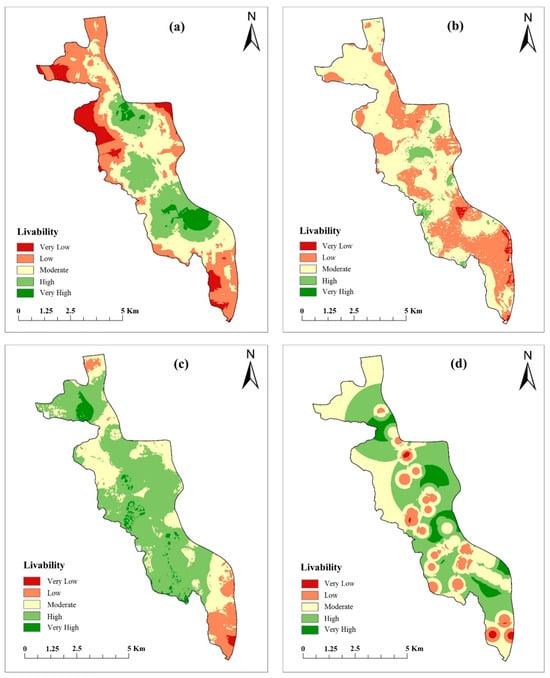

Easy access to facilities and services offers a hassle-free life for city residents. It is a necessity that directly impacts their daily lives. Areas closer to the city center offer easy access to a variety of facilities, like transportation, education, shopping, entertainment, employment opportunities, and so on. Thus, areas closer to the city center stand out as more accessible, and highly livable, whereas peripheral areas exhibit lower livability due to the greater distance to reach the city center. When categorized into different livability tiers (Figure 8), the map of the convenience dimension of urban livability (Figure 9a) displays a distinctive spatial pattern that departs from a random geography (Moran’s I = 0.28, p-value < 0.001). It is marked by large clusters of high to very high convenience along the mid-sections of the city (wards no. 6, 7, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 23), surrounded by lower convenience towards the periphery, especially the northern and southern reaches of the city. This distribution highlights that a significant portion of the city falls into the low and moderate livability categories, indicating a considerable scope for enhancing convenience-related aspects.

Figure 8.

Percentage of land areas under each livability status by dimensions.

Figure 9.

Livability status of Khulna City in terms of (a) convenience, (b) amenity, (c) health, and (d) safety.

4.1.3. Amenity Dimension

The amenity aspect emphasizes adequate infrastructures and spaces, which provide residents with comfort and enjoyment. Areas with sufficient infrastructures and spaces indicate higher livability compared to the areas that lack or are distant from this essential urban asset. Breaking down livability levels, the city can be segmented into distinct livability tiers (Figure 8). While overall, the city has a lower livability through the lens of amenities, the map in (Figure 9b) indicates a strongly clustered spatial pattern (Moran’s I = 0.91, p-value < 0.001). Specifically, the city center (wards no. 5, 6, 7, 18, 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31) is suffering from a severe lack of essential amenities, including vegetation cover, open spaces, water areas, and recreational facilities. The distribution reveals that a large portion of the city needs significant improvement in amenities, especially its central areas.

4.1.4. Health Dimension

Access to healthcare services, such as hospitals or clinics, safe drinking water, proper distance from manufacturing districts, better air quality, and so on, prioritizes health and promotes overall well-being. Areas having these characteristics reveal a higher livability status compared to those that do not. From a health perspective, the city’s overall livability is quite high (Figure 8). However, the urban livability map of the health dimension (Figure 9c) presents a geographic pattern that is strongly clustered and contrasted (Moran’s I = 0.97, p-value < 0.001). In the southern part of the city, particularly in wards no. 30 and 31, livability significantly declines because of saline drinking water. Addressing the issue of saline water is crucial to improve livability in these areas.

4.1.5. Safety Dimension

The safety dimension allows people to live without worrying about threats or being harmed. Living in areas close to police and fire stations enhances safety and livability. Moreover, areas far from major road intersections or gas stations also have better livability status as they have lower accident and fire incident risks. Through the lens of safety, Khulna City’s livability is good overall (Figure 8) (numerical values are in Table A3), but the livability map of the safety dimension (Figure 9d) indicates heterogeneity that follows a clustered spatial pattern (Moran’s I = 0.99, p-value < 0.001). A few of the central areas (wards no. 6, 9, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, and 26) exhibit lower livability due to the proximity to major road intersections, which occasionally leads to serious traffic accidents as well as increased noise and air pollution. Considering this, urban traffic management and pollution control measures can be an effective way to improve livability.

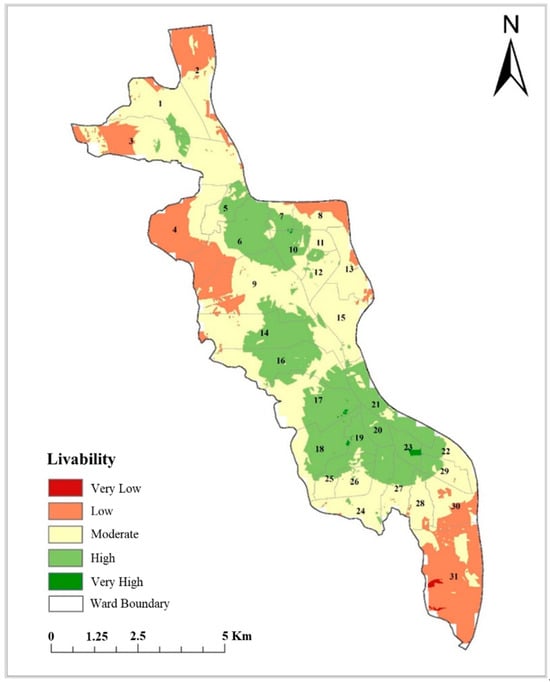

4.1.6. Overall Urban Livability Status

The overall livability scenario in Khulna City, as depicted by the map in Figure 10, reveals that local disparities are consistent with a significantly clustered geographic pattern as a whole (Moran’s I = 0.97, p-value < 0.001). The central areas of the city boast a high livability status, offering residents easy access to essential amenities and services in particular. Notably, wards 5, 6, 7, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 23 are strategically situated close to these high-livability zones, benefiting from a better quality of life. On the other hand, living away from these central areas towards the peripheries of the city, a noticeable decline in livability becomes evident. While the city as a whole exhibits a moderate level of livability, there are striking disparities. The upper northern and lower southern parts of the city face challenges in terms of livability status. These areas are distant from the city’s center, resulting in reduced connectivity, a lack of essential services, limited access to drinkable water, and the presence of manufacturing activities, which pose health risks to residents. Urgent attention is required for wards 2, 3, 4, 8, 13, 30, and 31, as they face significant livability challenges. Improvements in these regions are imperative to provide residents with a healthier and more conducive living environment. By addressing these concerns, urban planners and policymakers can work towards creating a more balanced and inclusive livability landscape for residents of Khulna City.

Figure 10.

Urban livability mapping for Khulna City.

4.2. Insights from City Dwellers

4.2.1. Determinants of Urban Livability from People’s Perspectives

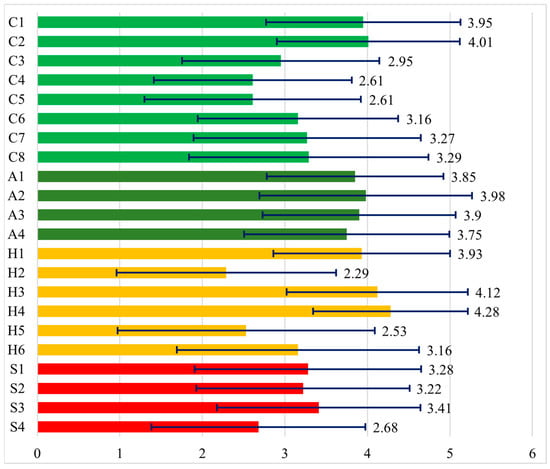

Valuable insights into how residents of Khulna City conceive of urban livability on the basis of their own lived experiences can be gained from the simple distributional properties of a standard set of livability indicators such as those discussed earlier in this article (Figure 11). The average score of each indicator reveals the importance residents show towards these factors when making decisions about where to live and therefore their degree of concern regarding a more livable place from each perspective. The scores have been assessed using a five-point Likert scale. This permits us to assess the convergence of views held by the local citizens and those expressed by the urban planning experts.

Figure 11.

Average subjective scoring on the indicators of urban livability and their standard deviation: (C1) distance to city center, (C2) distance to major road, (C3) distance to bus terminal, (C4) distance to train station, (C5) distance to post office, (C6) distance to library, (C7) distance to secondary school, (C8) distance to primary school, (A1) vegetation coverage, (A2) availability of open space, (A3) availability of water areas, (A4) distance to recreation facilities, (H1) distance to hospital, (H2) distance to manufacturing district, (H3) air quality, (H4) drinking water quality, (H5) soil salinity, (H6) urban heat island, (S1) distance to major road intersections, (S2) distance to police station, (S3) distance to fire station, (S4) distance to gas station.

When considering the convenience dimension, people have prioritized proximity to the city center and to major roads as the two most influential factors (3.95 and 4.01, respectively), as these aspects enable connectivity to essential facilities located in central areas of the city and ensure reaching other services with easy access. Also, proximity to educational institutions has emerged as another significant advantage (3.27 to 3.29), as people think that being close to schools provides more safety and accessibility for their children. However, the library, bus station, train station, and post office hold less draw in people’s residential preferences and therefore in shaping their vision of the livable city (3.16, 2.95, 2.61 and 2.61 respectively).

With regard to the amenity dimension, respondents have shown their desire to a similar degree towards all four factors. People think that recreational facilities, greenery, open space, and water areas collectively play a significant role in a more satisfying and high-quality living experience (all are above 3.5).

From the health perspective, people have expressed their strong consideration for drinking water quality and air quality (scores of 4.28 and 4.12, respectively). Being situated along the Rupsha River, a nearby section of the city is plagued by saline water, which is commonly considered unhealthy. Additionally, high levels of dust and pollutants downgrade air quality in the core commercial urban areas; as a result, people rate these factors as a major concern. Also, people place a premium on having a health care facility readily accessible (3.93). Conversely, other health-related factors are comparatively less of a concern to local residents (less than 3.25).

When it comes to safety considerations, people have shown similarly high levels of preference for proximity to a fire station and police station (3.41 and 3.22 respectively), perceiving that this closeness mitigates the potential harm or risks. Moreover, they have also prioritized the distance from major road intersections for a noise-free and less polluted environment (3.28). Gas stations hold the least importance in terms of the safety considerations (2.68).

To sum up, residents have a clear sense of what livability conditions may be in Khulna City. Average scores exhibit a broad range across indicators, from a minimum of 2.29 for the distance to manufacturing districts to a maximum of 4.28 for drinking water quality. Also, it is clear that Khulna City residents have diverse views on what livability may entail and what conditions bundle together to create more livable places and geographic environments. Standard deviations across the sample (Figure 11) are notably high, which underscores the role of people’s personal experiences in filtering their perspectives on urban livability, a point that will be brought up again later in the article. Altogether, these findings can serve as a reliable source of information for city planners and policymakers, helping them to prioritize their efforts towards improving the factors that have importance to residents. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the average subjective scores on the 22 indicators are largely in line with the opinions expressed by the urban planning experts who informed us during the AHP implementation reported earlier in this paper. Therefore, this concordance lends credence to the objective assessment of urban livability in Khulna City that was conducted on the basis of the AHP analysis. Yet, the broad variance of scorings intimates that objective assessment of livability is not sufficient to convey the state of conditions across the urban space and that personal experiences rooted in social and economic circumstances as well as spatially grounded contexts matter to a considerable extent. This is now further studied.

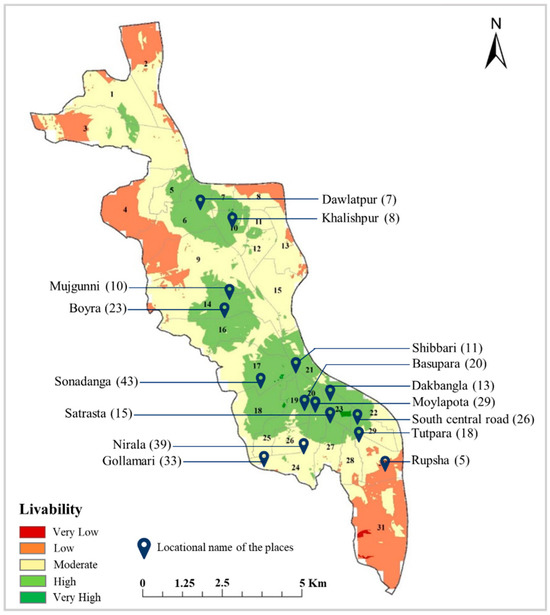

4.2.2. Subjective Livability in Khulna City

Survey respondents were prompted to name the three neighborhoods they consider as having the highest degree of livability in Khulna City at the present time. Overall, the three locations that garner the greatest numbers of endorsements are Sonadanga, Nirala, and Gollamari, with response rates of 43%, 39%, and 33%, respectively (Figure 12). Forming a second tier, the areas of Moylapota, South Central Road, and Boyra garnered moderate responses at 29%, 26%, and 23%, respectively, while other areas received significantly fewer responses. The fifteen locations that received non-trivial endorsement (over 5) are all situated in rather close proximity to each other. The geography of living preferences along with the spatial pattern of urban livability from objective findings indicate that the central sections of the city are more livable than peripheral areas (Figure 12). Hence, the living preferences of city dwellers align well with the observed pattern of livability found in the objective findings of our analysis. From the opinions expressed by residents, the preferred locations demonstrate that, on the whole, the central parts of the city are highly preferable to live, which also supports the outcome of the AHP and MCDM analysis. Even though two of the highly desired neighborhoods identified by city dwellers, Nirala and Gollamari, somewhat depart from the objective findings, they stand out as emerging areas that have seen significant improvements in their service and facility offerings towards a better quality of life. Notwithstanding these cases, the preferences of livable areas by city dwellers are in agreement with the spatial pattern of urban livability identified from the objective findings of urban livability mapping for Khulna City.

Figure 12.

Aggregated preferences expressed by residents for most livable places to live (endorsement percentages) and geographic distribution of objective livability index.

The reasons behind these preferences are multifaceted (Figure 13). A significant number of individuals cited the presence of a wide range of services, the convenient proximity to the city center, and easily accessible transportation facilities as the driving factors behind their choices. Moreover, the top-ranked areas were perceived as well-planned with better infrastructure systems, standard road widths, and a serene and clean environment, making them attractive to potential residents. Enhanced security measures, ample green spaces, improved sanitation, and efficient waste management systems were also highlighted as contributing factors to the favorable disposition towards these areas. These data illustrate a clear trend towards urban planning and infrastructure quality influencing the residential choices of Khulna City’s inhabitants. The findings emphasize the importance of considering these factors in future urban development and city planning initiatives to create more livable and attractive areas for residents.

Figure 13.

Word cloud of reasons supporting living preferences.

4.2.3. Reasons for Not Relocating to Favorite Living Areas

However, it is crucial to understand why certain individuals may decide not to relocate to their favorite living areas. While their endorsement of Sonadanga, Nirala, and Gollamari as ideal places to live is quite overwhelming, they have mentioned a few reasons that prevent them from residing in these areas. According to the respondents, several common factors deter individuals from relocating to their highly regarded areas (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Word cloud of reasons for not relocating to favorite living areas.

One of the most prevalent reasons is the cost of living. While these preferred places are considered highly desirable, the elevated living expenses, encompassing housing, utilities, and other amenities, often exceed the budgetary constraints of many; this may lead them to seek alternative options.

A respondent from the Rupsha slum stated it as follows:

“Although we aspire to reside in those areas, the cost of living there is beyond our means. As low-income individuals, it becomes exceedingly challenging to sustain our households amidst the rising expenses, making it unattainable for us to afford a decent place to live.”

Another significant reason that discourages people from relocating is their attachment to their own homes or ancestral properties. The presence of a homestead or ancestral home often binds them to their current location, even if they express a desire to move elsewhere.

A respondent from Religate stated it as follows:

“As this is my ancestral home where I grew up and have been living here for a long time, I don’t feel any problem, everything is fine with facilities and I have some business of my own, due to which I do not want to relocate to the area.”

Social connections play a significant role in relocation decisions, fostering a sense of familiarity and belonging. This connection and sense of belonging make it challenging for individuals to relocate to a different place where a new social network would need to be woven. Individuals who have spent a substantial amount of time in their current area find it challenging to sever the bonds they have forged with the community. This sense of connection and belonging becomes a powerful deterrent to moving to a different place.

A respondent from Dawlaatpur stated the following:

“We have been living in this area for almost 14 years and have developed a special relationship and bonding with the people of the area. Everyone knows each other and behaves like family because of this I don’t want to leave the familiar area and go to another area”.

Considering the distance to one’s workplace is another essential factor. A lengthy commute can be both time-consuming and costly, leading many individuals to opt for living closer to their current workplace, even if living conditions are less attractive. The added time and expenses associated with a longer commute often discourage individuals from relocating to their better-regarded locations.

A respondent from Rupsha stated it as follows:

“I am an employee of Caritas and have been living in Rupsha for four long years as my workplace is nearer to here. As moving home away from the workplace will increase both my travel time and cost. That’s why I choose this location to live in.”

For some families, the proximity to their children’s school becomes a significant consideration. Many individuals prioritize living in areas near school to ensure their children can safely and confidently commute to and from school.

A respondent from Boyra stated the following:

“The only reason we live here is because my daughter’s school is very close. Since she is young, it is convenient for us to bring her to school and pick her up, especially since her father is often at work. Additionally, having a nearby residence allows flexibility for my daughter to come and go to school safely or fearlessly.”

In conclusion, the reasons for not relocating to areas with high livability are diverse and deeply rooted in personal, financial, and social considerations. These factors highlight the importance of personal attachments, financial constraints, and practicality in making decisions about where to reside.

5. Discussion

5.1. Level of Coexistence Between Subjective and Objective Measures: Embracing Broader Planning Principles

This study highlights the intricate interplay between subjective perception and objective indicators in assessing urban livability, which is complex and often not as straightforward as one might expect. It has been found that the objective indicators are often rooted in the subjective experiences and preferences of city dwellers, underscoring the critical role of local community input in shaping urban living environments. As highlighted by previous research [2], the livability concept encompasses a broad range of considerations including both subjective experiences and objective realities, which establish a connection between individual well-being, livable communities, and a sustainable environment. This dual essence of livability highlights the necessity for more balanced urban planning. Such interconnections reaffirm the vital role of community engagement in the urban planning process, reflecting the fundamental principles of Jane Jacobs [50], to consider bottom-up insights from local populations alongside traditional top-down planning practice. This is echoed by our findings, which highlight the fact that livability cannot be completely grasped by using just objective measures.

This study demonstrates a substantial overlap between the two approaches, particularly in central areas where high accessibility and service clustering align with residents’ preferences for convenience and proximity to amenities. However, there are nuanced differences in priorities; for instance, while objective measures emphasize physical infrastructure and environmental factors, subjective perceptions highlight the importance of social dynamics and functional needs such as safety and mobility. Although central districts are objectively rated higher due to their concentration of amenities, residents sometimes express concerns about overcrowding or limited green spaces. Conversely, peripheral areas, often rated lower in objective assessments due to fewer facilities, are sometimes preferred for their quieter environments and perceived safety. These findings resonate with the Compact City Model, which advocates for high-density, mixed-use development and efficient transport systems to address both convenience and accessibility, while also emphasizing walkability and vibrant public spaces as promoted by New Urbanism. These subtle differences suggest that urban livability is shaped by the interaction of structural and individual factors, highlighting the need for a holistic and inclusive approach.

The findings align with a previous study in Dhaka, Bangladesh that showed that subjective perceptions of safety, accessibility to basic services, and environmental health significantly shape residents’ experiences of livability in dense neighborhoods [69]. This concurrence suggests a more holistic strategy to incorporate localized community feedback and subjective experiences to actually improve the quality of life for all citizens when developing urban landscapes [2]. However, in Dhaka, challenges such as noise pollution and traffic congestion further exacerbate subjective dissatisfaction, a factor less pronounced in Khulna’s urban environment. This comparison illustrates the relative advantages and challenges unique to mid-sized cities like Khulna versus larger megacities like Dhaka. This comparison illustrates the unique socio-economic challenges of cities in the Global South, where theories such as Resilience and Adaptive Urban Planning emphasize the need for flexibility in addressing these pressures while ensuring equitable and inclusive growth. Another recent work of research [70] has also emphasized the significance of the participatory approach in local-level urban planning by illustrating how integrated feedback from community people can effectively address the multiple social, economic, and environmental aspects in developing strategies at a local level. This participatory approach is closely tied to the “just city” framework, which emphasizes spatial justice and equitable access to urban amenities for all residents, especially marginalized populations. This participatory approach aligns with the findings of our study, where residents’ subjective preferences provide vital insights into improving objective livability factors, ultimately guiding urban growth in a more inclusive and sustainable direction. Researchers have argued that incorporating the needs and preferences of the population in the city planning and neighborhood design leads to more sustainable and satisfactory outcomes [53]. This participatory approach strongly aligns with the findings of our study, highlighting that community-driven insights are crucial for improving the objective factors in an effective manner to guide urban growth sustainably.

The locational factors and the agglomeration of facilities play a crucial role in shaping urban livability, as evidenced by a recent study [54], which emphasizes that locations with better pedestrian accessibility tend to attract a higher concentration of community facilities, including retail centers, parks, and other amenities. Recent research in Barishal highlights the importance of urban open spaces in fostering livability, with residents expressing dissatisfaction due to insufficient maintenance and accessibility [71]. This coexistence is particularly evident in Khulna, where subjective preferences for proximity to schools, workplaces, and markets complement objective indicators of accessibility but also point to overlooked concerns like recreational spaces and public safety. In Khulna, residents have shown a preference for functional needs like proximity to workspaces and schools, even when environmental amenities such as parks and open spaces are less prioritized in subjective assessments. This prioritization reflects the socio-economic realities of mid-sized cities where livelihood concerns often take precedence over recreational or aesthetic considerations.

In comparison to studies in Raiganj, India, where spatial livability assessments showed declining livability in peripheral regions due to inadequate access to infrastructure [3], our study similarly found peripheral areas of Khulna to exhibit lower livability scores. However, the incorporation of subjective preferences, such as proximity to educational facilities and markets, offers a more nuanced understanding of this dynamic in Khulna. Continuing this perspective, our findings also reveal that while the objective analysis of urban livability identifies the central districts as boasting a significantly higher degree of livability compared to the outlying regions, the subjective perceptions of city dwellers also illuminate their desire for accessibility and convenience. This finding is echoed in research conducted in small cities like Mongla and Noapara, where rapid urbanization and insufficient infrastructure development created disparities in accessibility, emphasizing the role of social processes and local governance in shaping urban livability [72]. The objective assessment validates these subjective preferences, indicating that areas closer to service amenities are perceived as more livable. This resonates with other findings, where the effects of visual space indicators on resident’s subjective perceptions have been demonstrated [73], hence the significance of considering both subjective and objective perception together in shaping urban livability. This dual focus on structural accessibility and subjective convenience mirrors the Healthy Cities Framework, which emphasizes clean air, sanitation, and health-promoting urban environments to enhance both physical and mental well-being.

Researchers also found that most livable areas identified by the geographic model overlapped with individuals’ preferred living environments [6]. Residents emphasize the importance of living close to their workplace, urban centers, schools, major roads, etc., which are markers of a preference for areas that offer more convenience and accessibility. This clustering effect of services and facilities is driven not only by proximity but also by individual preferences for multiple facilities in close proximity with reduced need for travel. The high density and centrality of these locations contribute significantly to the vibrancy and livability of urban neighborhoods [54]. This observation aligns with earlier works which posited that livability tends to progressively decrease as one moves away from the city’s central business district towards its periphery [51,74]. Residents prioritize proximity to convenience service areas over environmental concerns, strongly aligning with the 15 min city concept, which aims for allocating essential goods and services that are accessible within 15 min of travel.

So, this study underscores the importance of carefully planned urban form and community facility distribution in enhancing accessibility and promoting a livable urban environment. These findings underscore the importance of targeted investments in peripheral areas to improve access to services and infrastructure while preserving their quieter and safer characteristics. Such investments can alleviate pressure on central districts while promoting more balanced urban growth. The results advocate for urban planners to incorporate participatory approaches that address both immediate functional needs and long-term livability goals, particularly in the Global South where socio-economic and environmental challenges demand tailored, context-sensitive strategies. Incorporating these frameworks provides a blueprint for improving urban planning in cities like Khulna by ensuring equitable resource allocation and meaningful community engagement. These findings suggest the need to design urban spaces that balance accessibility with functional and recreational needs, ensuring that infrastructure investments are aligned with both community preferences and strategic urban planning frameworks.

Furthermore, it is impossible to ignore the influence that the physical environment plays in making cities livable. According to previous research [1], vegetation cover, water areas, and other natural environmental elements are important for raising urban comfort levels and making cities more livable overall. This study also suggests that while human thermal sensation is an important aspect of livability, relying solely on subjective measures may not provide urban planners with the precise findings needed for effective planning. Our results support this, highlighting the necessity of a well-rounded strategy that combines objective environmental measurements with subjective human experiences in order to attain sustainable urban livability.

5.2. Barriers to Relocation in Preferred Living Areas: Insights of City Dwellers

The findings reveal several underlying reasons for individuals to opt not to relocate to their preferred living locations, despite the universal desire for highly livable settings. In effect, this identifies the premises for dissonance between goals and aspirations on the one hand and between actions and behaviors on the other hand. For instance, the cost of living and affordability often create inner conflicts between personal desires and practical circumstances. In New York City, despite being reputed for better living, the high living cost has been found to lead to mixed feelings among residents [75]. Additionally, individuals’ emotions are significantly influenced by their social connections and familiarity with their surroundings. A few studies have stated that strong social connections may contribute to an individual’s own happiness [76]. Factors like birthplace and ancestral home further limit individual’s choices.

5.3. Limitations

Assessing urban livability status in Khulna City revealed significant challenges. The lack of a universally accepted definition of livability underscores its complex nature, which may vary by geographic location and cultural norms. However, this research explored the connections between objective geographic indicators and residents’ subjective perceptions, highlighting the importance of both perspectives in urban planning and policy making to enhance the overall livability of the city. Further investigation is needed to understand the relationship between livability and residents’ satisfaction, considering variables such as age, gender, occupation and income. While this study does not encompass these aspects, they warrant future exploration. Also, given the fast pace of socio-physical changes in mid-size cities such as Khulna City, cross-sectional studies represent only a snapshot entry point in understanding the causal chains of evolutionary dynamics in the complex geographies of human capital and livability. Longitudinal observatories are needed to channel energies and policies towards more sustainable urban futures.

6. Conclusions

This study has explored the correspondence between subjective perceptions and objective assessment of urban livability at fine spatial granularity in Khulna City, Bangladesh, by integrating residents’ experiences with geospatial analysis. The dual-method approach emphasized the coexistence of subjective and objective perspectives, underscoring their complementary roles in shaping urban livability. The objective analysis revealed a distinct pattern of livability, with central areas having higher livability status, while the peripheral areas show a declining nature. However, subjective assessments highlighted nuanced priorities, such as residents’ preferences for quieter environments in peripheral areas, despite their lower objective scores, and concerns about overcrowding in central districts. In addition, this research has confirmed that subjective preferences, such as proximity to workplaces, schools, and urban centers, are also reflected in and strongly aligned with the objective analysis, which reveals high communalities between subjective and objective perspectives in livability assessments.

The findings support the broader planning principle, especially advocating for socially inclusive urban growth models like the 15 min city concept, which can better serve the Global South’s unique challenges in rapidly urbanizing nations with uncontrolled expansion. Incorporating frameworks like the Compact City Model and Healthy Cities principles, this study highlights the importance of balancing accessibility with functional and recreational needs. Targeted investments in peripheral areas to enhance infrastructure and services while preserving their quieter characteristics can reduce pressures on central districts, fostering more balanced urban development. Given the notable points of departure in subjective perceptions of livability and other environment interactions with objective assessments, this study also offers valuable insights for fostering more inclusive, accessible, and sustainable urban environments by emphasizing community engagement and physical factors in the urban planning process that can guide more balanced and equitable urban growth, given the unique social and geographic dynamics of these regions of the Global South.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K.J. and M.Z.H.; methodology, P.K.J.; software, P.K.J.; validation, P.K.J., M.Z.H. and J.-C.T.; formal analysis, P.K.J.; investigation and data curation, P.K.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.J.; writing—review and editing, P.K.J., M.Z.H. and J.-C.T.; visualization, P.K.J.; supervision, M.Z.H. and J.-C.T.; project administration, M.Z.H. and J.-C.T.; funding acquisition, M.Z.H. and J.-C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were comprehensively briefed on the assurance of their anonymity, the purpose behind the research, and the potential utilization of the data in case of publication. As is standard in all research involving human subjects, ethical approval from the relevant ethics committee was secured.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the experts for generously sharing their invaluable insights, and to all individuals who contributed their perspectives in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Rescaling of indicators.

Table A1.

Rescaling of indicators.

| Indicator (Numerical Measurement Scale) | Ordinal Scale of Livability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low (1) | Low (2) | Moderate (3) | High (4) | Very High (5) | |

| Distance to city center | Over 1400 | 1200–1400 | 1000–1200 | 800–1000 | Under 800 |

| Distance to major road | Over 400 | 300–400 | 200–300 | 100–200 | Under 100 |

| Distance to bus terminal | Over 1400 | 1200–1400 | 1000–1200 | 800–1000 | Under 800 |

| Distance to train station | Over 1400 | 1200–1400 | 1000–1200 | 800–1000 | Under 800 |

| Distance to post office | Over 2000 | 1500–2000 | 1000–1500 | 500–1000 | Under 500 |

| Distance to library | Over 2000 | 1500–2000 | 1000–1500 | 500–1000 | Under 500 |

| Distance to secondary school | Over 900 | 700–900 | 500–700 | 300–500 | Under 300 |

| Distance to primary school | Over 500 | 400–500 | 300–400 | 200–300 | Under 200 |

| Vegetation coverage | Under −0.6 | −0.6–−0.2 | −0.2–0.2 | 0.2–0.6 | Over 0.6 |

| Availability of open space | 0 | -- | -- | -- | 1 |

| Availability of water areas | Under −0.6 | −0.6–−0.2 | −0.2–0.2 | 0.2–0.6 | Over 0.6 |

| Distance to recreation facility | Over 800 | 700–800 | 600–700 | 500–600 | Under 500 |

| Distance to hospital | Over 800 | 700–800 | 600–700 | 500–600 | Under 500 |

| Distance to manufacturing district | Under 300 | 300–500 | 500–700 | 700–900 | Over 900 |

| Air quality | Under 4.376 | 4.376–4.422 | 4.422–4.468 | 4.468–4.514 | Over 4.514 |

| Drinking water quality | Under 113.75 | 113.75–179.00 | 179.00–244.25 | 244.25–309−50 | Over 309.50 |

| Soil salinity | Over 0.6 | 0.2–0.6 | −0.2–0.2 | −0.6–−0.2 | Under −0.6 |

| Urban heat island | Over 15,268.3 | 15,216.1–15,268.3 | 15,163.8–15,216.1 | 15,111.6–15,163.8 | Under 15,111.6 |

| Distance to major road intersection | Under 200 | 200–300 | 300–400 | 400–500 | Over 500 |

| Distance to police station | Over 2000 | 1500–2000 | 1000–1500 | 500–1000 | Under 500 |

| Distance to fire station | Over 1700 | 1400–1700 | 1100–1400 | 800–1100 | Under 800 |

| Distance to gas station | Under 200 | 200–300 | 300–400 | 400–500 | Over 500 |

Table A2.

Prioritization of dimensions and indicators.

Table A2.

Prioritization of dimensions and indicators.

| Dimension | Indicator | Priority (% in Dimension) | Rank | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience (60%) | Distance to city center | 28.52 | 1 | 1 |

| Distance to major road | 22.82 | 2 | ||

| Distance to bus terminal | 14.16 | 3 | ||

| Distance to train station | 6.34 | 6 | ||

| Distance to post office | 1.64 | 8 | ||

| Distance to library | 3.56 | 7 | ||

| Distance to secondary school | 9.86 | 5 | ||

| Distance to primary school | 13.10 | 4 | ||

| Amenity (6%) | Vegetation coverage | 52.37 | 1 | 4 |

| Availability of open space | 15.25 | 3 | ||

| Availability of water areas | 6.09 | 4 | ||

| Distance to recreation facility | 26.29 | 2 | ||

| Health (23%) | Distance to hospital | 24.25 | 2 | 2 |

| Distance to manufacturing district | 17.75 | 3 | ||

| Air quality | 4.01 | 6 | ||

| Drinking water quality | 37.91 | 1 | ||

| Soil salinity | 9.09 | 4 | ||

| Urban heat island | 6.98 | 5 | ||

| Safety (12%) | Distance to major road intersection | 51.43 | 1 | 3 |

| Distance to police station | 30.45 | 2 | ||

| Distance to fire station | 11.58 | 3 | ||

| Distance to gas station | 6.54 | 4 | ||

| Overall Consistency Test: λ max = 4.24; CI = 0.08; RI = 0.9; CR = 0.087 | ||||

Table A3.

Land area and percentages under each livability status by considered dimension.

Table A3.

Land area and percentages under each livability status by considered dimension.

| Livability Status | Convenience | Amenity | Health | Safety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | Area (Sq.km) | (%) | Area (Sq.km) | (%) | Area (Sq.km) | (%) | Area (Sq.km) | |

| Very Low | 9.08 | 4.63 | 1.3 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

| Low | 30.69 | 15.65 | 36.63 | 18.68 | 8.98 | 4.27 | 9.58 | 4.89 |

| Moderate | 32.00 | 16.32 | 57.39 | 29.27 | 26.98 | 13.76 | 41.66 | 21.24 |

| High | 23.48 | 11.98 | 4.65 | 2.37 | 60.59 | 30.90 | 39.81 | 20.30 |

| Very High | 4.75 | 2.42 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 3.66 | 1.87 | 8.21 | 4.18 |

Appendix B

Table A4.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the dimensions.

Table A4.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the dimensions.

| Dimensions | Convenience | Amenity | Health | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Amenity | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.33 |

| Health | 0.20 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Safety | 0.20 | 3.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 |

Table A5.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight value for the dimensions.

Table A5.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight value for the dimensions.

| Dimensions | Convenience | Amenity | Health | Safety | Criterion Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.60 |

| Amenity | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Health | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| Safety | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Sum | 1.00 | ||||

Table A6.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the convenience dimension.

Table A6.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the convenience dimension.

| Convenience | DUC | DMR | DBT | DTS | DPO | DL | DSS | DPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUC | 1.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| DMR | 0.33 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| DBT | 0.33 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 0.33 |

| DTS | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| DPO | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| DL | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| DSS | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| DPS | 0.33 | 0.33 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Distance to city center = DUC, distance to major road = DMR, distance to bus terminal = DBT, distance to train station = DTS, distance to post office = DPO, distance to library = DL, distance to secondary school = DSS, and distance to primary school = DPS.

Table A7.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight for convenience dimension.

Table A7.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight for convenience dimension.

| Convenience | DUC | DMR | DBT | DTS | DPO | DL | DSS | DPS | Criterion Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUC | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| DMR | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| DBT | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| DTS | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| DPO | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| DL | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| DSS | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| DPS | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Sum | 1.00 | ||||||||

Table A8.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the amenity dimension.

Table A8.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the amenity dimension.

| Amenity | VC | AOS | AWA | DRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 |

| AOS | 0.20 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.33 |

| AWA | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 |

| DRF | 0.33 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 |

Vegetation coverage = VC, availability of open space = AOS, availability of water areas = AWA, and distance to recreation facilities = DRF.

Table A9.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight for the amenity dimension.

Table A9.

Normalized pairwise comparison and weight for the amenity dimension.

| Amenity | VC | AOS | AWA | DRF | Criterion Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.52 |

| AOS | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| AWA | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| DRF | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.26 |

| Sum | 1.00 | ||||

Table A10.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the health dimension.

Table A10.

Pairwise comparison matrix for the health dimension.