Exploring the Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior—Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

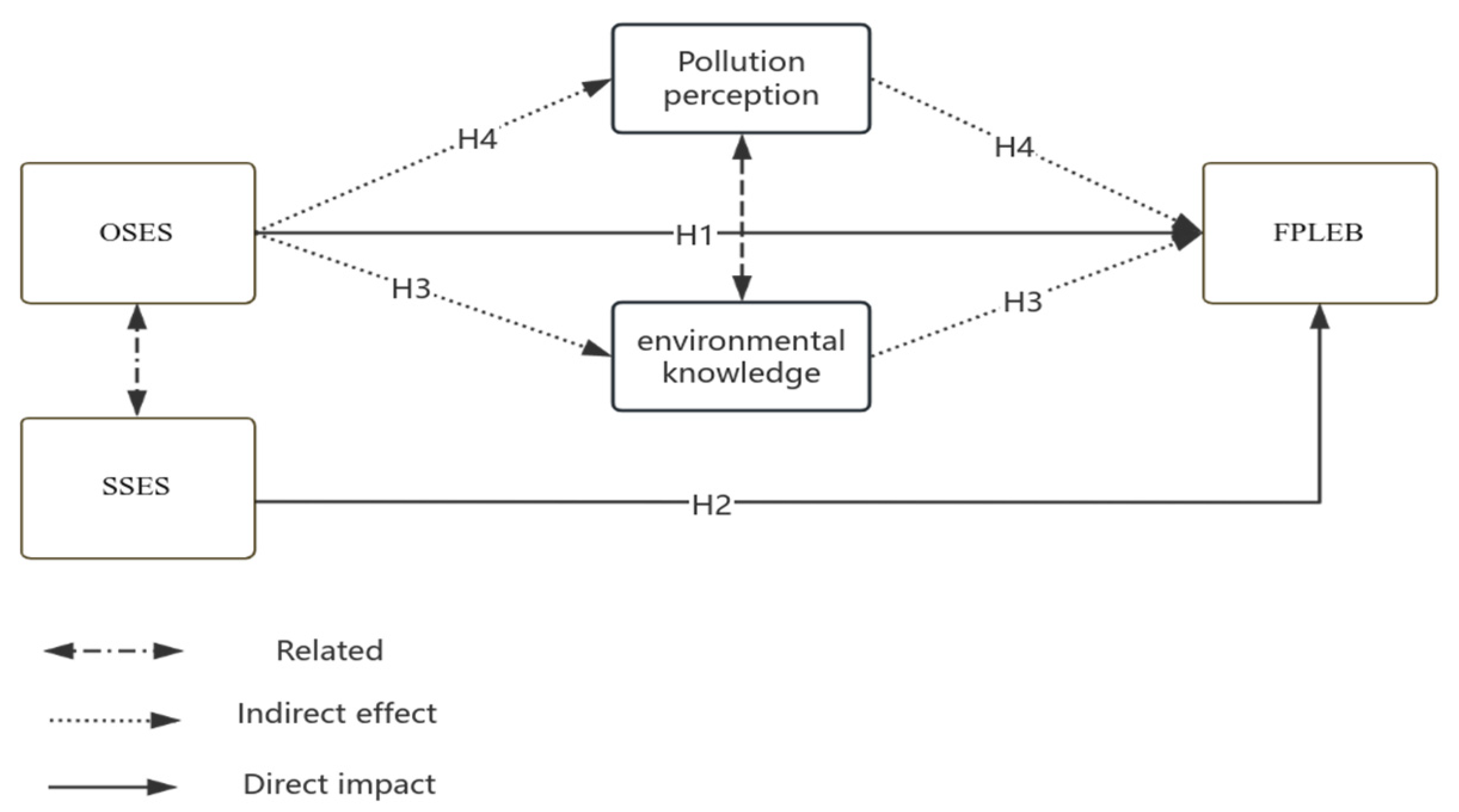

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Objective Socioeconomic Status

2.2. Subjective Socioeconomic Status of the Farmers

2.3. Mediating Effect of Environmental Cognition

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Probit Model

3.2.2. Mediation Effect Model

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior (FPLEB)

3.3.2. Socioeconomic Status (SES)

3.3.3. Environmental Cognition

3.3.4. Controlled Variables

4. Results

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.1.1. Oprobit Regression Result Analysis

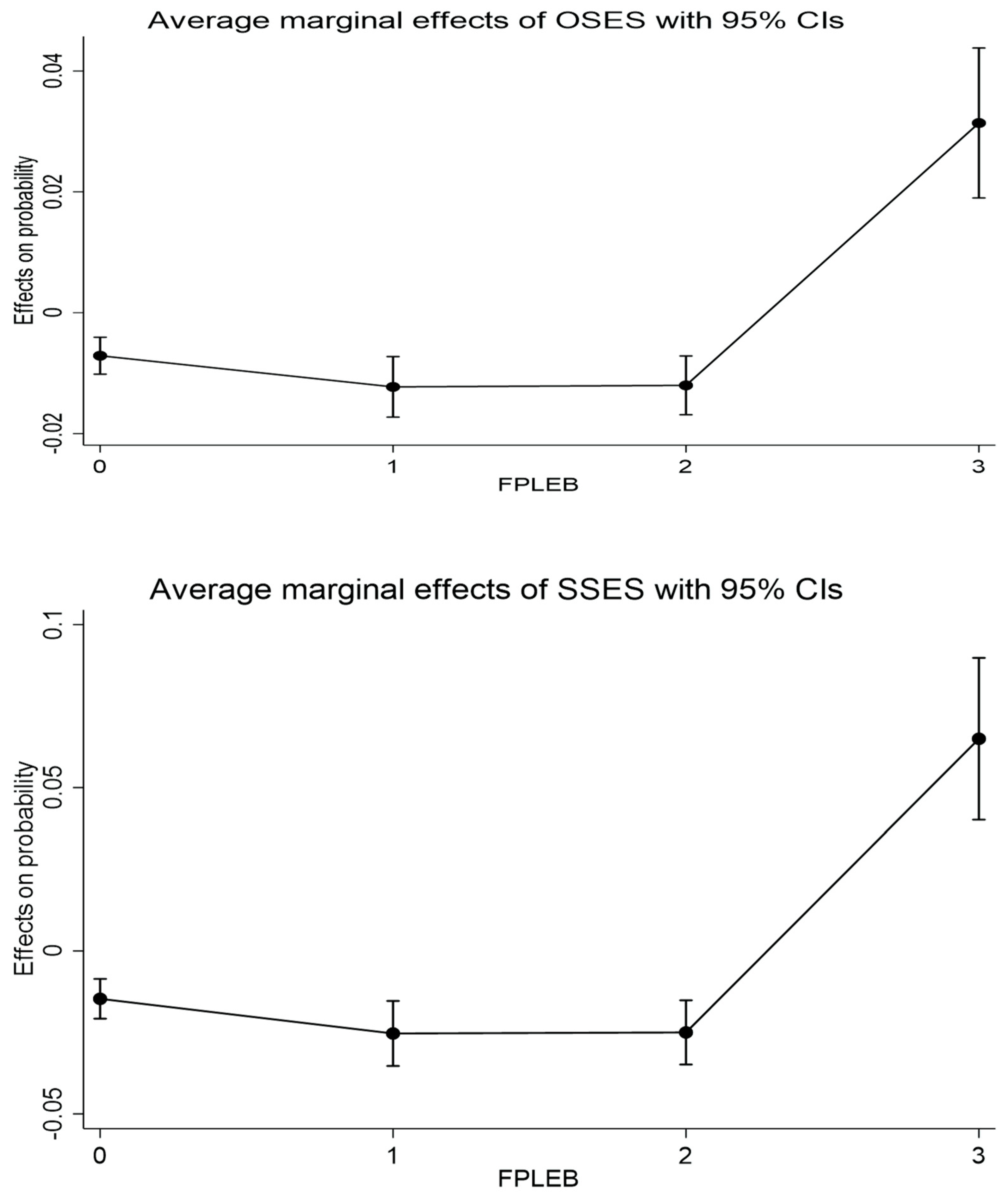

4.1.2. Marginal Effect Analysis

4.1.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.1.4. Robustness Test

4.2. Mediation Analysis

| Variables | Route | Effect Values | Boot Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval (BootCI) Lower Bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BootCI Lower | BootCI Upper | ||||

| OSES | Direct effect | 0.046 *** | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.070 |

| Environmental knowledge | Indirect effect | 0.013 *** | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.018 |

| OSES | Direct effect | 0.056 *** | 0.013 | 0.030 | 0.081 |

| Pollution cognition | Indirect effect | 0.003 * | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The World Bank Rural Population (% of Total Population). 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Xiao, C.; Zhou, J.; Shen, X.; Cullen, J.; Dobson, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, X. Rural Living Environment Governance: A Survey and Comparison between Two Villages in Henan Province of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Si, W. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Examining the Role of Ecological Value Cognition, Environmental Attitude, and Place Attachment among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202402/content_6934790.htm (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Liu, P.; Han, A. How does community leadership contribute to rural environmental governance? Evidence from shanghai villages. Rural Sociol. 2023, 88, 856–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.N.; Gao, Q.; Jin, L.S. The influence of rural household income and trust in village leaders on households’ willingness to treat the domestic solid wastes: Based on survey data of 465 households in yunnan province. Resour. Environ. 2021, 30, 2512–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Koondhar, M.A.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Kong, R. Perceived Value Influencing the Household Waste Sorting Behaviors in Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L. The Effect of Environmental Cognition on Farmers’ Use Behavior of Organic Fertilizer. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; He, K.; Zhang, J. The Influence of Clan Social Capital on Collective Biogas Investment. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and Social Factors That Influence Pro-Environmental Concern and Behaviour: A Review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Keh, H.T.; Chen, J. Assimilating and Differentiating: The Curvilinear Effect of Social Class on Green Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 47, 914–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, P.; Greig, W.H. Environmental Pollution Control: Two Views from the General Population. Environ. Behav. 1977, 9, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Delistavrou, A. Types and Influential Factors of Consumers’ Non-purchasing Ecological Behaviors. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, G.S.; Delgado, E.; Miller, D.; Gubbins, S. Transforming Values into Actions: Ecological Preservation through Energy Conservation. Couns. Psychol. 1993, 21, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.Q.; Xiao, H.; Xiaoning, Z.; Mei, Q. Influence of Social Capital on Rural Household Garbage Sorting and Recycling Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Class Identity. Waste Manag. 2023, 158, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Buttel, F.H.; Flinn, W.L. Social Class and Mass Environmental Beliefs: A Reconsideration. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K. Social Class, Control, and Action: Socioeconomic Status Differences in Antecedents of Support for pro-Environmental Action. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 77, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, S.; Chen, H. Nonmonotonic Effects of Subjective Social Class on Pro-Environmental Engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Lyu, H.; Li, X. Social Class and Subjective Well-Being in Chinese Adults: The Mediating Role of Present Fatalistic Time Perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 5412–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, E.C.; McGrath, J.J. Community, family, and subjective socioeconomic status: Relative status and adolescent health. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lyu, H. Social status and subjective well-being in Chinese adults: Mediating effect of future time perspective. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 2101–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandin, A.; Guillou, L.; Abdel Sater, R.; Foucault, M.; Chevallier, C. Socioeconomic Status, Time Preferences and pro-Environmentalism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Long, Q. Prediction of Environmental Cognition to Undesired Environmental Behavior—The Interaction Effect of Environmental Context. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.H.; Abid, M.; Yan, T.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Akhtar, S.; Faisal, M. Understanding Farmers’ Intentions to Adopt Sustainable Crop Residue Management Practices: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W. Environmental Concern Has a Weaker Association with Pro-Environmental Behavior in Some Societies than Others: A Cross-Cultural Psychology Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N.; Cosset, J.-C.; Saffar, W. Political Connections of Newly Privatized Firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2008, 14, 654–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Nie, J. The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Rucker, D.D.; Galinsky, A.D. Social Class, Power, and Selfishness: When and Why Upper and Lower Class Individuals Behave Unethically. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigkas, M.; Partalidou, M.; Lazaridou, D. Trust and Other Historical Proxies of Social Capital: Do They Matter in Promoting Social Entrepreneurship in Greek Rural Areas? J. Soc. Entrep. 2021, 12, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.; Rottman, J. The Burden of Climate Action: How Environmental Responsibility Is Impacted by Socioeconomic Status. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 77, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Franzen, A. The Wealth of Nations and Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wen, Y.; Gao, J. What Ultimately Prevents the Pro-Environmental Behavior? An in-Depth and Extensive Study of the Behavioral Costs. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 158, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much; Macmillan Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781250056115. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux, A.; Marmot, M.G.; Adler, N.E. Does Subjective Social Status Predict Health and Change in Health Status Better than Objective Status? Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going Green to Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Sarkar, A.; Zhang, F. How Capital Endowment and Ecological Cognition Affect Environment-Friendly Technology Adoption: A Case of Apple Farmers of Shandong Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.T.; Zhang, J.B. How does environmental regulation affect the willingness of farmers to participate in environmental governance in the village. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 34, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C.Z.; Chen, H.Y. How Perceived Fairness and Subjective Happiness Affect Individual’s Pro-Environmental Behavior——Moderating Effects Based on Environmental Knowledge. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2024, 39–50+125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How Does Environmental Knowledge Translate into pro -Environmental Behaviors?: The Mediating Role of Environmental Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, D.E.; Hornback, K.E.; Warner, W.K. The environmental movement: Some preliminary observations and predictions. In Social Behavior, Natural Resources and the Environment; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Sun, Z.; Huang, M. The Impact of Digital Literacy on Farmers’ pro-Environmental Behavior: An Analysis with the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1432184. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, M.; Zhao, K. Study on the influence of family socioeconomic status on farmers’ environmentally friendly production behaviors. J. Northwest A&F Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 20, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.H.; Zhang, Y.X. Impact of Farmers’ Social Stratification on Land Transfer Behavior: From the Perspective of Wealth Capital and Prestige Capital. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Ying, H.; Li, X.; Tong, L. Association between Socioeconomic Status and Mental Health among China’s Migrant Workers: A Moderated Mediation Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Alper, C.M.; Doyle, W.J.; Adler, N.; Treanor, J.J.; Turner, R.B. Objective and Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. How Does Social Interaction Affect Pro-Environmental Behaviors in China? The Mediation Role of Conformity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 690361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir-Ozdes, A.; Strickland-Hughes, C.M.; Bluck, S.; Ebner, N.C. Future Perspective and Healthy Lifestyle Choices in Adulthood. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milfont, T.L.; Wilson, J.; Diniz, P. Time Perspective and Environmental Engagement: A Meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, K.; Kim, J.H. Factors determining the social participation of older adults: A comparison between Japan and Korea using EASS 2012. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194703. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Lewis, N.A.; Ballew, M.T.; Bravo, M.; Davydova, J.; Gao, H.O.; Garcia, R.J.; Hiltner, S.; Naiman, S.M.; Pearson, A.R.; et al. What Counts as an “Environmental” Issue? Differences in Issue Conceptualization by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Information Entropy e | Utility Value d | Weight Coefficient w |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSES | Cadres’ status | 0.756 | 0.243 | 0.526 |

| Education level | 0.977 | 0.023 | 0.049 | |

| Relationship network | 0.986 | 0.014 | 0.030 | |

| Household income | 0.996 | 0.012 | 0.011 | |

| Financial assets | 0.986 | 0.005 | 0.031 | |

| Housing assets | 0.837 | 0.163 | 0.353 |

| Variables | Definition | Evaluation | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPLEB | Number of participants in three types of environmental governance behaviors, including sewage treatment, garbage sorting, and the use of flushable toilets | No participation = 0; 1 type of participation = 1; 2 types of participation = 2; and 3 types of participation = 3 | 2.223 | 0.818 |

| SES | OSES | Lower level = 1; middle and lower = 2; middle = 3; middle and upper = 4; and upper = 5 | 2.966 | 1.414 |

| SSES | 1 = very low; 2 = relatively low; 3 = general; 4 = relatively high; and 5 = very high | 2.941 | 0.700 | |

| Environmental knowledge | Knowledge of rural habitat improvement | 1 = have not heard of it; 2 = have heard of it but do not know much about it; 3 = know a little about it; 4 = Know a lot; and 5 = Very well understood | 2.739 | 1.330 |

| Pollution perception | Impacts on rural ecosystems (deterioration of water quality, contamination of soil, etc.) caused by indiscriminate dumping and non-separation of household waste | 1 = very small; 2 = relatively small; 3 = average; 4 = relatively large; and 5 = very large | 4.168 | 0.796 |

| Impacts on the community environment (village appearance and order of life in the village) caused by the haphazard accumulation and non-separation of household garbage | 1 = very small; 2 = relatively small; 3 = average; 4 = relatively large; and 5 = very large | 4.171 | 0.807 | |

| Gender | Gender | Male = 1 and female = 0 | 0.925 | 0.263 |

| Age | Age | Year | 63.207 | 10.311 |

| Health | Self-identified health status | 1 = incapacitated; 2 = poor; 3 = medium; 4 = good; and 5 = excellent | 4.001 | 1.097 |

| Minority households | Whether it is a minority household | 1 = yes and 0 = no | 0.030 | 0.171 |

| Agricultural laborers | Several members of the family worked in agriculture | Number of people working in agriculture | 1.418 | 0.997 |

| Terrain | Topography of the village | 1 = plains and 2 = hills | 1.165 | 0.371 |

| Location | The village is located in the city suburb | 1 = yes and 0 = no | 0.372 | 0.483 |

| Distance | The distance between the village committee and the county seat | Kilometer | 18.784 | 12.602 |

| Social norm | Household waste sorting can be appreciated and praised | 1 = Completely disagree; 2 = do not quite agree; 3 = general; 4 = agree more; and 5 = agree very much | 4.152 | 0.857 |

| Social pressure | Whether the government should publicize the classification of rural domestic waste | 1 = yes and 0 = no | 0.848 | 0.359 |

| Variables | FPLEB | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| OSES | 0.091 *** | |

| (0.019) | ||

| SSES | 0.188 *** | |

| (0.037) | ||

| Gender | 0.041 | 0.065 |

| (0.095) | (0.094) | |

| Age | −0.010 *** | −0.012 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Health | 0.131 *** | 0.120 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | |

| Minority households | −0.056 | −0.048 |

| (0.146) | (0.146) | |

| Agricultural laborers | −0.034 | −0.043 |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | |

| Terrain | 0.574 *** | 0.556 *** |

| (0.077) | (0.077) | |

| Location | 0.374 *** | 0.362 *** |

| (0.054) | (0.054) | |

| Distance | −0.002 | −0.003 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Social norm | 0.089 ** | 0.095 ** |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Social pressure | 0.754 *** | 0.756 *** |

| (0.068) | (0.068) | |

| No. of respondents | 2086 | 2086 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.097 | 0.097 |

| Variables | Present-Oriented | Both Present- and Future-Oriented | Future-Oriented |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSES | 0.049 | 0.090 ** | 0.166 ** |

| (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.054) | |

| SSES | 0.253 *** | 0.046 | 0.263 * |

| (0.058) | (0.060) | (0.104) | |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| No. of respondents | 879 | 898 | 264 |

| Variables | OSES | SSES | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replacement Variable | Replacement Model | Replacement Variable | Replacement Model | |

| SES | 0.145 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.167 * | 0.126 *** |

| (0.041) | (0.012) | (0.073) | (0.024) | |

| Gender | −0.202 | 0.027 | −0.131 | 0.039 |

| (0.215) | (0.062) | (0.211) | (0.061) | |

| Age | −0.003 | −0.005 ** | −0.006 | −0.007 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.002) | |

| Health | 0.139 ** | 0.094 *** | 0.136 ** | 0.086 *** |

| (0.046) | (0.016) | (0.046) | (0.016) | |

| Minority households | −0.135 | −0.044 | −0.129 | −0.039 |

| (0.286) | (0.094) | (0.284) | (0.094) | |

| Agricultural laborers | 0.014 | −0.017 | 0.005 | −0.023 |

| (0.055) | (0.016) | (0.056) | (0.016) | |

| Terrain | 1.098 ** | 0.316 *** | 1.057 ** | 0.305 *** |

| (0.375) | (0.046) | (0.371) | (0.046) | |

| Location | 0.338 ** | 0.234 *** | 0.316 * | 0.227 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.034) | (0.129) | (0.034) | |

| Distance | 0.005 | −0.001 | 0.004 | −0.002 |

| (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.001) | |

| Social norm | 0.113 | 0.063 ** | 0.120 * | 0.067 *** |

| (0.059) | (0.019) | (0.058) | (0.019) | |

| Social pressure | 0.361 ** | 0.537 *** | 0.370 ** | 0.538 *** |

| (0.122) | (0.046) | (0.122) | (0.046) | |

| No. of respondents | 2088 | 2086 | 2088 | 2086 |

| R2 | 0.193 | 0.195 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.125 | 0.114 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Tan, S.; Yuan, R. Exploring the Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior—Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041502

Yang L, Tan S, Yuan R. Exploring the Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior—Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041502

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lisha, Shuang Tan, and Rao Yuan. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior—Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041502

APA StyleYang, L., Tan, S., & Yuan, R. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environmental Governance Behavior—Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability, 17(4), 1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041502