Circular Economy Practices in Fashion Design Education: The First Phase of a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

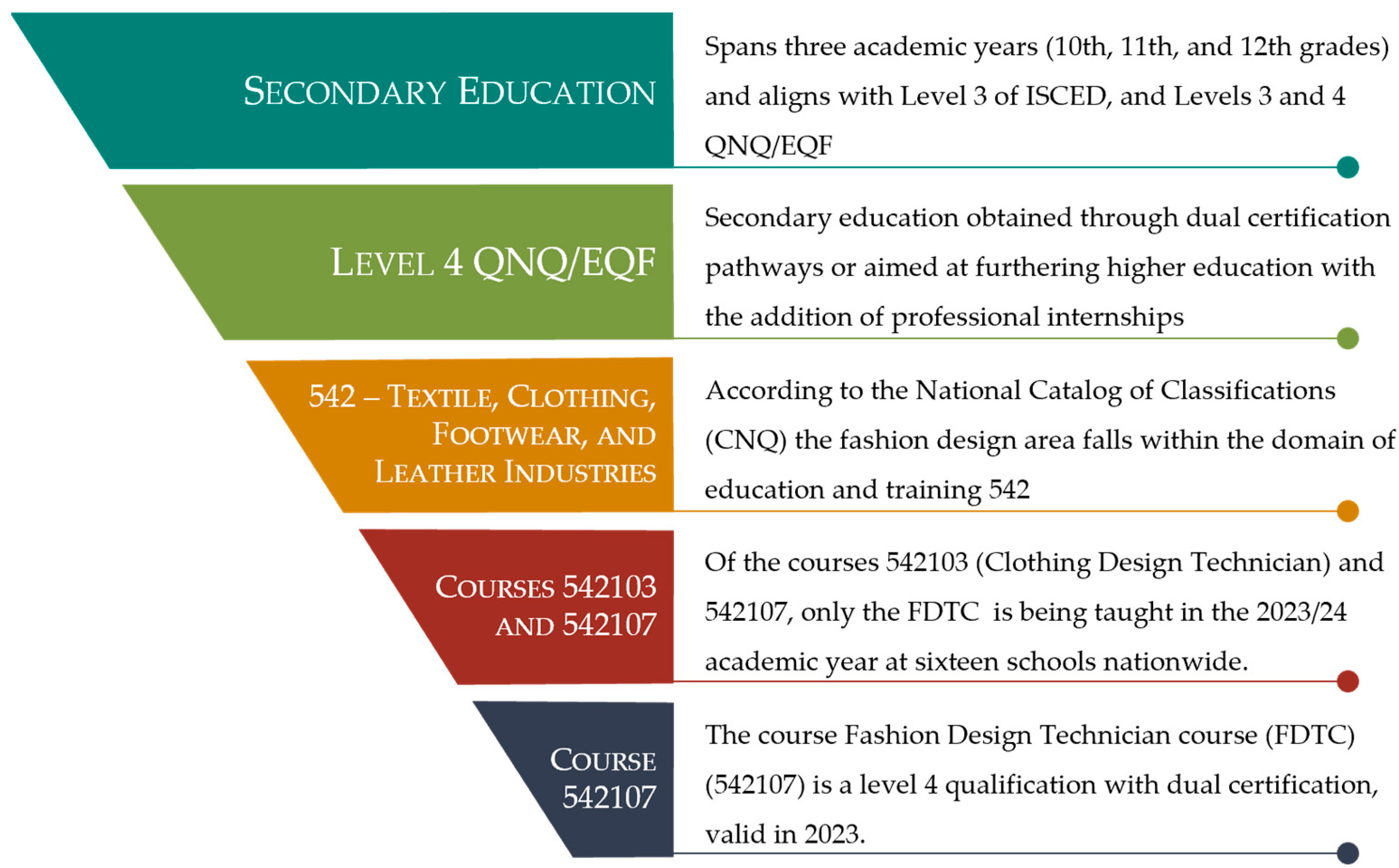

2.1. Study Object

Circular Economy and Sustainability in the Fashion Design Technician Course Curriculum

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

- Evaluating the emphasis placed on sustainability issues in the curriculum of the discipline(s) taught by teachers in the course’s study program.

- Identifying sustainability concepts already embedded in the curriculum of the discipline(s) within this course’s study program, as indicated by educators.

- Establishing connections between disciplines and UFCDs taught, and the integration and significance attributed to sustainability issues within this course.

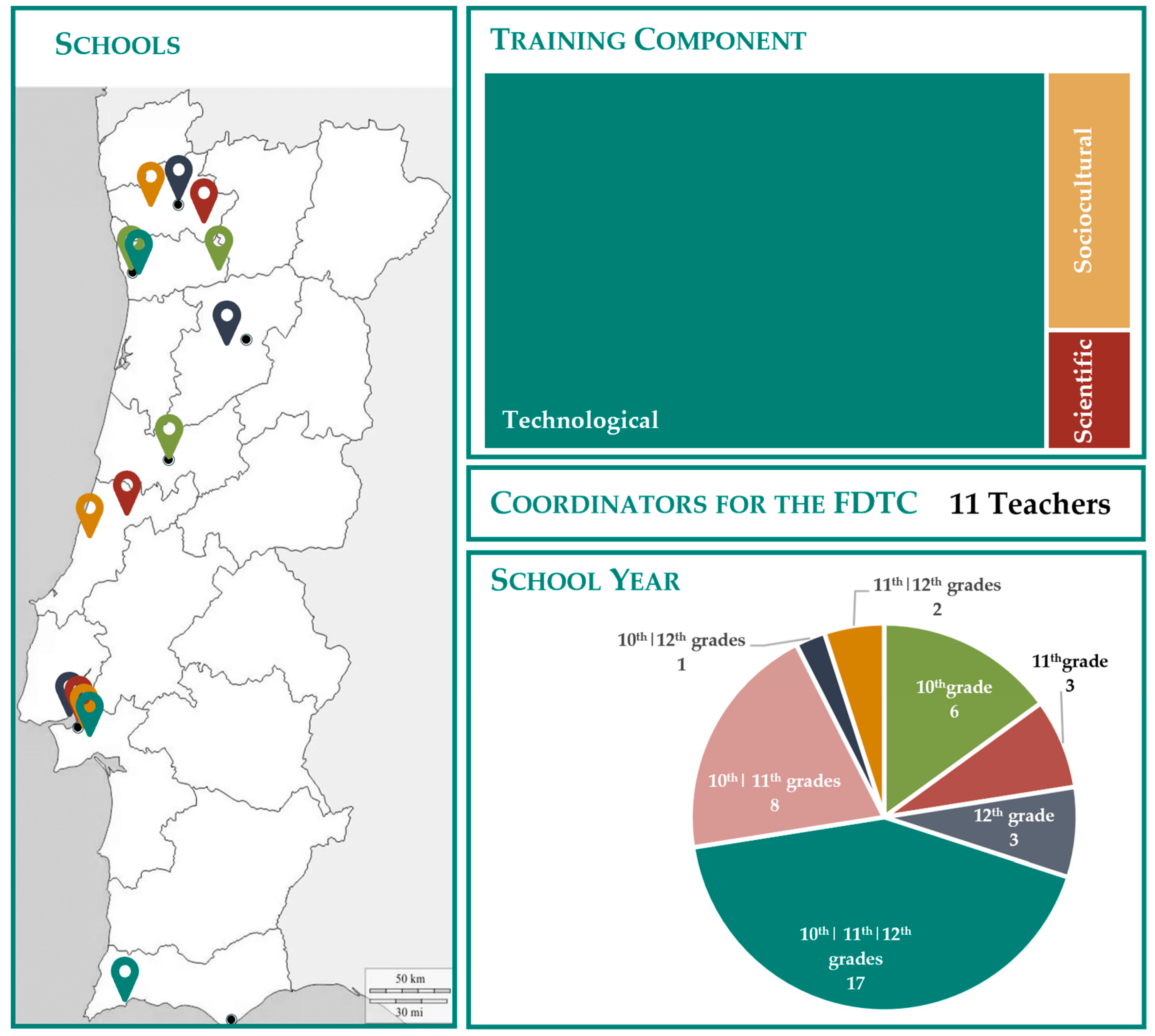

Sample

3. Results and Discussion

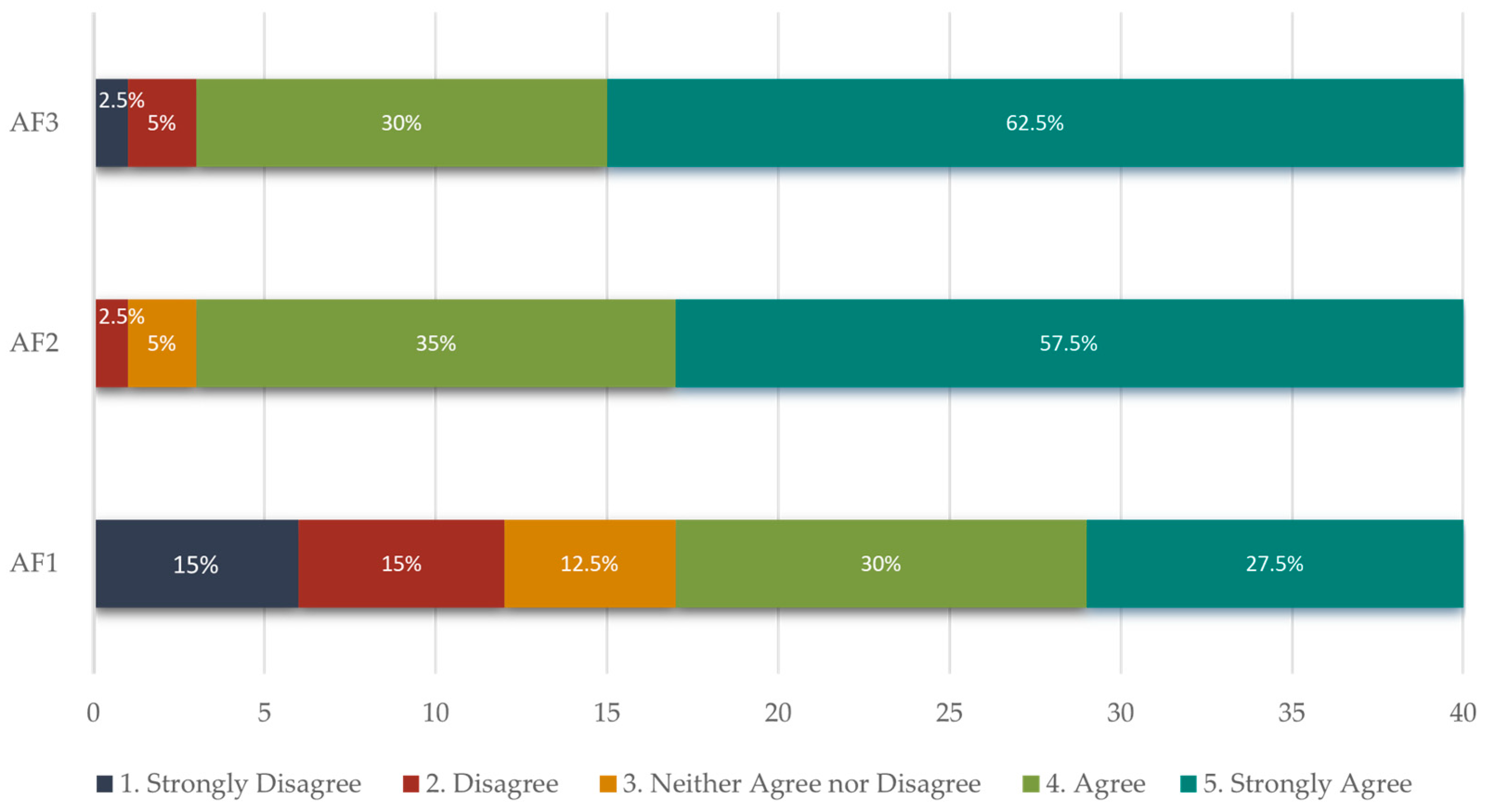

3.1. Circular Economy and Sustainability in the Fashion Design Technician Course Curriculum—Perspective of the Surveyed Teachers

- AF1. Sustainable development is integrated into the curriculum of the subject(s) or UFCDs I teach;

- AF2. The integration of environmental issues (environmental protection) should be a fundamental component in all subjects I teach;

- AF3. Sustainable development should be addressed not only within the subjects of my specific area but also integrated into all curricula as a cross-cutting theme;

3.2. Circular Economy and Sustainability in the Pedagogical Practice of the Surveyed Teachers

4. Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Circle Economy. Circularity Gap Report 2024: Closing the Global Circularity Gap. 2024. Available online: https://www.circularity-gap.world/2024 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The Circular Economy in Higher Education–Insights from Course Offerings in London and New York. 2021. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/eychfk79tktg-grlsty/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Vision of a Circular Economy for Fashion. 2020. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/nbwff6ugh01m-y15u3p/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Sarker, M.R.; Islam, M.; Marma, U.A.S.; Alam, M.M.; Shabur, M.A.; Rahman, M.S. Circular economy strategies: A fuzzy DEMATEL decision framework for the fast fashion footwear manufacture. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition, Volume 1. 2013. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-1-an-economic-and-business-rationale-for-an (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Bonelli, F.; Caferra, R.; Morone, P. In need of a sustainable and just fashion industry: Identifying challenges and opportunities through a systematic literature review in a Global North/Global South perspective. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.; Casamayor, J.L.; Ramirez, M.; Moreno, M.; Faludi, J.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Sustainable product design education: Current practice. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innovat. 2021, 7, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Hołuj, D. Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Dewberry, E. Demi: A case study in design for sustainability. Int. J. High. Educ. 2002, 3, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart, M.; McDonough, W. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, T.; Dan, C. Circling round change. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2021), Herning, Denmark, 9–10 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, L.; Cabral, I.; Cunha, J. Color in Sustainable Fashion: A Reflection on the Importance of Design Education. In Advances in Design, Music and Arts II. EIMAD 2022; Raposo, D., Neves, J., Silva, R., Correia Castilho, L., Dias, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 25, pp. 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.; Bardecki, M.; Searcy, C. Tools for sustainable fashion design: An analysis of their fitness for purpose. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, L. Fashion design education for sustainability practice. Reflections on undergraduate level teaching. In Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles. Values, Design, Production and Consumption; Gardetti, M.A., Torres, A.L., Eds.; Routledge/Green Leaf Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Dewberry, E.; Goggin, P. Sustainable Consumption by Design. In Exploring Sustainable Consumption: Conceptual Issues and Policy Perspectives; Cohen, M., Murphy, J., Eds.; Elseiver: London, UK, 2001; pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, F.E.; Freire, L.H.; da Cunha, J.L.F.L. The 7 Complex Lessons from Edgar Morin Applied in Fashion Design Education for Sustainability. In Advances in Design, Music and Arts II. EIMAD 2022; Raposo, D., Neves, J., Silva, R., Correia Castilho, L., Dias, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 25, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collina, L. Designing design education: An articulated programme of collective open design activities. Des. J. 2017, 20, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binde, M.; Freimane, A. Is there a zero in a fashion design? In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2022), London South Bank University, London, UK, 8–9 September 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/uiwtaHvud8YIG_uiSTauTlJH74/A%20New%20Textiles%20Economy%3A%20Redesigning%20fashion%E2%80%99s%20future.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Onur, D.A. Integrating Circular Economy, Collaboration and Craft Practice in Fashion Design Education in Developing Countries: A Case from Turkey. Fash. Pract. 2020, 12, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Law of the Education System. Lei n.º 46/86, de 14 de outubro, com alterações introduzidas por: Lei n.º 115/97; Lei n.º 49/2005; Lei n.º 85/2009; Lei n.º 16/2023. Diário da República eletrónico. 1986. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/lei/1986-34444975 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. 2012. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Decree, n. º 782/2009, de 23 de julho. Diário da República Eletrónico, 1ª Série, n.º 141, 4776–4778. 2009. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2009/07/14100/0477604778.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Rocha, A.L.; Guia Interpretativo do Quadro Nacional de Qualificações. Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e Ensino Profissional, IP. 2014. Available online: https://anqep.gov.pt/np4/file/312/QNQ_GuiaInterpretativoQNQ_2014.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- ANQEP Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional, IP. Catálogo Nacional de Qualificações (CNQ)–Qualificações de dupla certificação. 2008. Available online: https://catalogo.anqep.gov.pt/qualificacoesPesquisa (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Moreira, S.; Dinis Marques, A. Education for the circular economy: Analysis of the high school curriculum for fashion design courses in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 16th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED2022), Online Conference, 7–8 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Educational Offer Portal-Portal da Oferta Educativa. Available online: https://www.ofertaformativa.gov.pt (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Decree n.º 1291/2006 de 21 de novembro. Diário da República Eletrónico, 1.ª Série, n.º 224, 8000–8001. 2006. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2006/11/22400/80008001.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Decree-Law n.º 396/2007, de 31 de dezembro. Diário da República Eletrónico, 1.ª Série, n.º 251, 9165–9173. 2007. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2007/12/25100/0916509173.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Order n.º 13456/2008, de 14 de maio. Diário da República Eletrónico, 2.ª Série, n.º 93, 21591–21597. 2008. Available online: https://files.diariodarepublica.pt/2s/2008/05/093000000/2159121597.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Boletim do Trabalho e Emprego (BTE), de 22 de julho. n.º 27, vol. 87, 2302–2400. 2020. Available online: http://bte.gep.msess.gov.pt/completos/2020/bte27_2020.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- ANQEP Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional, IP. Catálogo Nacional de Qualificações (CNQ)–Técnico(a) de Design de Moda (alterado a 22 de julho de 2020). 2008. Available online: https://catalogo.anqep.gov.pt/qualificacoesDetalhe/7276 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- ANQEP Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional. Programas e Aprendizagens Essenciais-Cursos Profissionais. Available online: https://www.anqep.gov.pt/np4/240.html (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Moreira, S.; Marques, A.D. Circular Economy and Sustainability in the Fashion Design Technician Course: Questionnaire Survey. Repositório de Dados da Universidade do Minho. 2024. Available online: https://datarepositorium.uminho.pt/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.34622/datarepositorium/GVGTRK (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Sousa, E.; Marques, A.D.; Broega, A.C. Ensino da moda centrado na sustentabilidade: Instituições de ensino em Portugal com cursos em moda sustentável. In Proceedings of the 4º CIMODE 2018–International Fashion and Design Congress, Madri, Spain, 10 July 2018; ISBN 978-989-54168-0-6. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, S.; Montagna, G.; Félix, M.J. Weaving the Gap: Giving a Place to Textile Design in Portuguese Higher Education. In Perspectives on Design III. Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Raposo, D., Neves, J., Silva, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 34, pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-toolkit-for-policymakers (accessed on 16 April 2024).

| Component 1 | Discipline or UFCD |

|---|---|

| Sociocultural Training | Portuguese and Portuguese as a Non-Native Language (PLNM) Foreign Language I, II, or III Integration Area Physical Education Information and Communication Technology (ICT) or School Offer Citizenship and Development |

| Scientific Training | Descriptive Geometry History and Culture of the Arts Mathematics Moral and Religious Education |

| Technological Training | Basics of Jeanswear Jeanswear Design Project Basics of Streetwear Streetwear Design Project Development of Women’s Classics Women’s Apparel Design Project Development of Men’s Classics Men’s Apparel Design Project Dress Pattern Transformation Shirt Pattern Transformation Skirt and Pants Pattern Transformation Coat Pattern Making Apparel Assembly Apparel Manufacturing Bitmap Image and Vector Drawing Relationship Fashion Design Project Using CAD CAD Illustration Graphic Composition Commercial Fashion Design Project Creative Fashion Design Project Individual Collection Planning Individual Collection Development Volume Experimentation Prototype Modeling Prototype Construction Final Garment Construction |

| Work Context Training | Workplace training in vocational courses constitutes an autonomous component. Workplace training aims to help students acquire and develop technical, relational, and organizational skills relevant to the professional qualification to be obtained and is subject to its own regulation. |

| Theme | Yes | No | Already Present in the Curriculum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sustainable development and its goals (SDGs) | 18 | 6 | 16 |

| 2. Climate change | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| 3. Global warming | 19 | 12 | 9 |

| 4. Pollution | 20 | 9 | 11 |

| 5. Release of microplastics into water resources | 21 | 11 | 8 |

| 6. Biodiversity loss | 18 | 13 | 9 |

| 7. Renewable/alternative energies | 23 | 12 | 5 |

| 8. Circular economy | 19 | 7 | 14 |

| 9. Polluter-pays principle | 20 | 16 | 4 |

| 10. Fast fashion | 16 | 9 | 15 |

| 11. Excessive consumption | 23 | 3 | 14 |

| 12. Destruction of natural resources | 20 | 9 | 11 |

| 13. Excessive use of pesticides and insecticides | 17 | 16 | 7 |

| 14. Textile waste | 17 | 10 | 13 |

| 15. Reuse | 23 | 2 | 15 |

| 16. Recycling | 23 | 3 | 14 |

| 17. Redoing | 23 | 2 | 15 |

| 18. Product repair | 23 | 9 | 8 |

| 19. Upcycling | 18 | 11 | 11 |

| 20. Eco-products | 21 | 8 | 11 |

| 21. Greenwashing | 18 | 12 | 10 |

| 22. Slow design | 21 | 9 | 10 |

| 23. Product durability | 17 | 9 | 14 |

| 24. Composting | 13 | 23 | 4 |

| Total | 471 | 231 | 258 |

| Pedagogical Strategies |

|---|

| “Research, debate, and reflection” “Viewing documentaries and critical assessments of them. Completing practical assignments on various topics, all with oral presentations (…)” “Dialogue with students (…)” “Videos, discussion, and written and oral activities” “Dialogue with students, (…); Presentation of informational content (…); Prioritization of design solutions with a digital focus; Regular dialogue with students (…); Encouragement of analysis and critical reflection on current affairs.” “Upcycling project (…) Study of textile materials (…) Workshops and lectures on sustainability, circular economy, and slow fashion. (…) Presentation of projects to the school community (…)” “Research on specific situations, visits to exhibitions, documentaries, etc.” “(…) project on textile fibers and research eco-sustainable fibers (…)” “Researching materials, seeking sustainable raw materials at fashion fairs, (…)” “Debates on the topic, viewing videos, sharing projects and designers (…)” “Providing information, study visits, application projects, interdisciplinary teaching practices” “Viewing and analyzing case studies on the impact of fashion and the textile industry, documentaries, films” “Guidance in researching and practicing sustainable options in fashion design and execution of projects” “Problem-Based Learning methodology. Practical activities. Socio-emotional education” “Case analysis, workshops on upcycling” “Diverse information, research, and application of knowledge to practice” “Explain the linear economy and its problems. (…) Recommend authors and/or sources for consultation.” “I try to give examples (…).“ “ (…) In the classroom, I suggest and sometimes we watch parts of programs related to sustainable fashion, such as ‘Wardrobe’ on RTP 2; reports, such as ‘The Clothes of Dead White Men’, where the journalist has visited our school. (…) As exercises, I propose many from the book ‘Sustainable Fashion’ by GG.” |

| Cultural, Social, and Environmental Impact |

|---|

| “(…) all students can be aware of the topics, raise awareness of the problems, and discuss what can be done for individual and global improvement.” “Dialogue with students about the importance of preserving nature and the environment we are in, as well as the harmful consequences of exercising in areas with high levels of pollution.” “Dialogue with students, based on consumption estimates, about optimizing resource management in each developed project; Presentation of informative content on material production and its implications in terms of raw materials and extraction processes; Prioritization of project solutions focusing on the digital aspect; Regular dialogue with students about environmental, developmental, geopolitical, production, and consumption issues; Encouragement of analysis and critical reflection on current affairs.” “(…) Study of textile materials and understanding of their environmental impact (from cultivation or collection to the design of the pieces and their distribution). Workshops and lectures on sustainability, circular economy, and slow fashion topics. (…) Presentation of the projects to the school community to raise awareness of the topic.” “All work proposals always have a related question. For example, in the last proposal, students were asked to do a project on textile fibers and research eco-sustainable fibers, specifying characteristics, origin, and application. We also utilize our textile waste to create new fabrics later. This year we will create new materials with classroom leftovers to make objects to be sold at a circular economy fair we will have at the school in May.” “Research of materials, searching for sustainable raw materials at fashion fairs, monitoring the market for fashion trends related to sustainability.” “Debates on the topic, viewing videos, sharing projects and designers who integrate sustainable development in their practice, (…), etc.” “Reuse of fabrics/clothing practicing the Upcycling technique. (…) Reuse of denim presented in a parade in partnership with the Vouzela City Council.” “Viewing and analyzing case studies on the impact of fashion and the textile industry, documentaries, films.” “I incorporate, whenever possible, topics directly related to environmental sustainability issues in work proposals, such as upcycling strategies, reuse, recycling, and new product construction. Fashion with added value based on extending its life cycle.” “Projects developed with material reuse; waste separation in the classroom.” “Explaining the linear economy and its problems. Emphasizing ’knowledge is power’. Suggesting more sustainable alternative paths. (…)” “(…) In more practical work, we reuse all the scraps from cutting pieces to make new fabrics or new pieces. We have our project ‘Trocas e Baldrocas’, which involves bringing clothes we no longer use, and students exchange them among themselves. (…)” |

| Innovation and Creativity |

|---|

| “Utilizing materials (e.g., fabrics and others) for more creative work” “Reusing fabrics/clothing using the upcycling technique. Coordinated development/dresses on mannequins with dried plants in a forest environment. Reusing denim presented in a fashion show in partnership with the Vouzela City Council” “Upcycling as a form of creative unlocking” “Explain the linear economy and its problems. Link ‘knowing how is power’. Suggest more sustainable alternative paths. Recommend authors and/or sources for consultation.” |

| Resource Management |

|---|

| “I don’t use paper.” “Reuse of materials (paper, writing materials), sharing of manuals.” “Utilizing materials (e.g., fabrics and others) for more creative projects.” “Dialogue with students, based on consumption estimates, about optimizing resource management in each developed project; (…) Prioritization of project solutions focusing on the digital aspect; (…)” “Upcycling project (…), we collect all the waste, gathering and using them in future projects. (…) Many of the textile materials used in the creation of our pieces are second-hand (…)” “Alert to waste, reuse of materials with an understanding of the process, multiple use of created pieces.” “(…) We also utilize our textile waste to create new fabrics later. This year we will create new materials with classroom leftovers to make objects to be sold at a circular economy fair we will have at the school in May.” “Reuse of fabrics/clothing practicing the Upcycling technique. (…) Reuse of denim (…)” “Avoid paper and fabric waste. Reuse fabrics. When not necessary, avoid leaving tools and devices plugged in. Avoid water waste. Keep materials clean.” “(…), such as upcycling strategies, reuse, recycling, and new product construction. (…)” “Upcycling (…)” “Reuse of materials and equipment, alteration of existing models, and transformation into new products.” “Projects developed with material reuse; waste separation in the classroom.” “Reuse, zero waste, recycling.” “Reuse of fabrics for garment making.” “(…) In more practical work, we reuse all the scraps from cutting pieces to make new fabrics or new pieces. We have our project ‘Trocas e Baldrocas’, which involves bringing clothes we no longer use, and students exchange them among themselves.” |

| Practical Applications |

|---|

| “I don’t use paper.” “Utilizing materials (e.g., fabrics and others) for more creative projects.” “Upcycling project (…); in the development projects of new pieces, we collect all the waste, gathering and using them in future projects. (…) Many of the textile materials used in the creation of our pieces are second-hand. (…)” “Alert to waste, reuse of materials with an understanding of the process, multiple use of created pieces.” “(…) For example, in the last proposal, students were asked to do a project on textile fibers and research eco-sustainable fibers, specifying characteristics, origin, and application. We also utilize our textile waste to create new fabrics later. This year we will create new materials with classroom leftovers to make objects (…)” “Research of materials, searching for sustainable raw materials at fashion fairs, monitoring the market for fashion trends related to sustainability.” “Viewing and analyzing case studies on the impact of fashion and the textile industry, (…).” “Avoid paper and fabric waste. Reuse fabrics. (…)” “Guidance in researching and practicing sustainable options in the creation and execution of fashion projects.” “I incorporate, (…), such as upcycling strategies, reuse, recycling, and new product construction. Fashion with added value based on extending its life cycle.” “Upcycling as a form of creative unlocking.” “Case analysis, (…)” “Projects developed with material reuse; waste separation in the classroom.” “(…) In more practical work, we reuse all the scraps from cutting pieces to make new fabrics or new pieces. We have our project ‘Trocas e Baldrocas’, which involves bringing clothes we no longer use, and students exchange them among themselves. (…)” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreira, S.; Felgueiras, H.P.; Marques, A.D. Circular Economy Practices in Fashion Design Education: The First Phase of a Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17030951

Moreira S, Felgueiras HP, Marques AD. Circular Economy Practices in Fashion Design Education: The First Phase of a Case Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(3):951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17030951

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreira, Sofia, Helena P. Felgueiras, and António Dinis Marques. 2025. "Circular Economy Practices in Fashion Design Education: The First Phase of a Case Study" Sustainability 17, no. 3: 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17030951

APA StyleMoreira, S., Felgueiras, H. P., & Marques, A. D. (2025). Circular Economy Practices in Fashion Design Education: The First Phase of a Case Study. Sustainability, 17(3), 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17030951