Challenging to Change? Examining the Link Between Public Participation and Greenwashing Based on Organizational Inertia

Abstract

1. Introduction

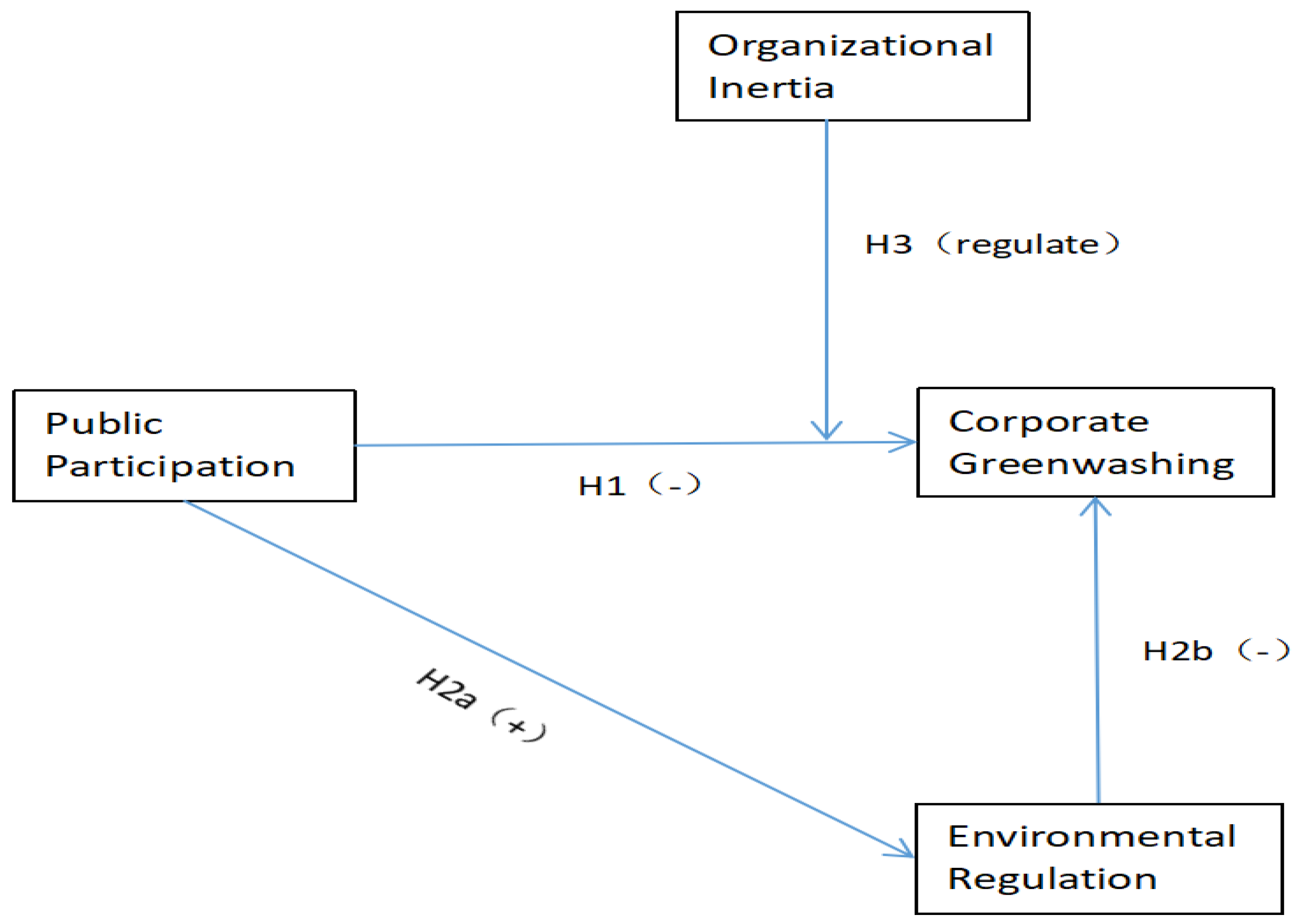

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Public Participation and Corporate Greenwashing

2.2. Public Participation, Environmental Regulation and Corporate Greenwashing

2.3. Public Participation, Organizational Inertia, and Corporate Greenwashing

3. Research Design

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Independent Variable

3.3. Dependent Variables

3.4. Intermediary Variable

3.5. Moderator Variable

3.6. Control Variable

3.7. Model Design

3.8. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

4. Main Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Robustness and Endogeneity Test

4.3. Mediation Effect Test

4.4. Moderating Effect Test

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Significance

5.3. Practical Significance

5.4. Innovation Point

5.5. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.; He, J.; Cai, L.; Du, M.; Huang, M. Accurate multi-objective prediction of CO2 emission performance indexes and industrial structure optimization using multihead attention-based convolutional neural network. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 337, 117759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnewe, E.; Yao, T.; Zaman, M. Informing or obfuscating stakeholders: Integrated reporting and the information environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3893–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kadach, I.; Ormazabal, G. Institutional investors, climate disclosure, and carbon emissions. J. Account. Econ. 2023, 76, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, M.J.; Danilova-Jensen, E.; Nielsen, M.; Rosdahl, C.G.; Schmidt, C.J. Defining greenwashing: A concept analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciabuschi, F.; Dellestrand, H.; Kappen, P. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Technology transfer competence, rent-seeking, and bargaining power. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. J. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, J. Plastic politics of delay: How political corporate social responsibility discourses produce and reinforce inequality in plastic waste governance. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2024, 24, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. The co-creation of social value: What matters for public participation in corporate social responsibility campaigns. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.; Ye, S. Window Dressing in Impression Management: Does Negative Media Coverage Drive Corporate Green Production? Sustainability 2024, 16, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyögg, G.; Sydow, J. Organizational path dependence: A process view. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.E.; Neimark, B.; Garvey, B.; Phelps, J. Unlocking “lock-in” and path dependency: A review across disciplines and socio-environmental contexts. World Dev. 2023, 161, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lu, X.; Jin, Y.; Meer, T.G. Pushing hands and buttons: The effects of corporate social issue stance communication and online comment (in) civility on publics’ responses. Public Relat. Rev. 2024, 50, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driss, H.; Drobetz, W.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O. The Sustainability committee and environmental disclosure: International evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2024, 221, 602–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.G.; Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M.; Árvai, J. The benefit of virtue signaling: Corporate sleight-of-hand positively influences consumers’ judgments about “social license to operate”. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, F.; Aragon-Correa, J.A. Greenwashing in corporate environmentalism research and practice: The importance of what we say and do. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, K.; Ryu, D. Corporate environmental responsibility: A legal origins perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Orazalin, N.; Uyar, A.; Shahbaz, M. CSR achievement, reporting, and assurance in the energy sector: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, L. The corporate social responsibility price premium as an enabler of substantive CSR. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2022, 47, 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimmerveen, L.; Ybema, S.; Nies, H. Who participates in public participation? The exclusionary effects of inclusionary efforts. Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.E.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Mann, J.; Sabherwal, R. Public participation in policy making: Evidence from a citizen advisory panel. Public Perform. Manag. 2022, 45, 1308–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langella, C.; Anessi-Pessina, E.; Botica Redmayne, N.; Sicilia, M. Financial reporting transparency, citizens’ understanding, and public participation: A survey experiment study. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, K.; Kaufmann, D. Actors, arenas and aims: A conceptual framework for public participation. Plan. Theory 2023, 22, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J. Governance edging out representation? Explaining the imbalanced functions of China’s people’s congress system. J. Chin. Gov. 2021, 6, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tao, L.; Yang, B.; Bian, W. The relationship between public participation in environmental governance and corporations’ environmental violations. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, M.; Aissaoui, A. Rooting for the green: Consumers and brand love. J. Bus. Strategy 2024, 45, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktadir-Al-Mukit, D.; Bhaiyat, F.H. Impact of corporate governance diversity on carbon emission under environmental policy via the mandatory nonfinancial reporting regulation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1397–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Segerson, K.; Wang, C. Is environmental regulation the answer to pollution problems in urbanizing economies? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 117, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizi, A.; Gentile, M.; Guarini, G.; Meliciani, V. The impact of environmental regulation on innovation and international competitiveness. J. Evol. Econ. 2024, 34, 169–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tang, W. Additional social welfare of environmental regulation: The effect of environmental taxes on income inequality. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chandio, A.A.; Farooq, U.; Sahito, J.G.M.; He, G. Assessing the impact of mechanism of green public consumption policy on environmental equity: Evidence from China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.W. Public participation and trust in government: Results from a vignette experiment. J. Policy Stud. 2023, 38, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhiveeran, J.; Orr, M. Examining the impact of social media use, political interest, and canvassing on political participation of the american public during the 2020 Presidential Campaigns. J. Policy Pract. Res. 2023, 4, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herian, M.N.; Hamm, J.A.; Tomkins, A.J.; Pytlik Zillig, L.M. Public participation, procedural fairness, and evaluations of local governance: The moderating role of uncertainty. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 815–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Cao, C.; Qiu, H.; Xie, Z. Impact of organizational inertia on organizational agility: The role of IT ambidexterity. Inform. Technol. Manag. 2021, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Wetering, R.; Krogstie, J. Building dynamic capabilities by leveraging big data analytics: The role of organizational inertia. Inform. Manag. 2021, 58, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjadi, B.; Soewarno, N.; Sutarsa, A.; Jermias, J. Effect of intellectual capital on organizational performance in the Indonesian SOEs and subsidiaries: Roles of open innovation and organizational inertia. J. Intellect. Cap. 2024, 25, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yi, Y.; Yuan, C. Bottom-up learning, organizational formalization, and ambidextrous innovation. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2011, 24, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, S.J.; Whittington, R. Reconfiguration, restructuring and firm performance: Dynamic capabilities and environmental dynamism. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. Top-management-team tenure and organizational outcomes: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1990, 35, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; He, X. CEO openness, strategy persistence and organizational performance: A study based on Chinese listed companies. J. Manag. Sci. China 2015, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, F.; Barkema, H. Pace, rhythm, and scope: Process dependence in building a profitable multinational corporation. Strategic Manag. J. 2002, 23, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksom, H. Institutional inertia and practice variation. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2022, 35, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Subsidy expiration and greenwashing decision: Is there a role of bankruptcy risk? Energ. Econ. 2023, 118, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Can environmental monitoring power transition curb corporate greenwashing behavior? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 212, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Sun, Y.; Xu, S. Financial report comment letters and greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2024, 127, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Nie, R.; Gao, X. Public Participation, Government Response and Corporate Environmental Performance: A Research Based on the Mediating Effects of Pollution Supervision and Resource Support. Financ. Res. 2022, 13, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. The Influence Mechanism of Media Attention on Green Technology Innovation of Heavily Polluting Enterprises: Based on the Mediating Effects of Government Environmental Regulation and Public Participation. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Z.W.; Xu, C.X.; Wu, Y. Business environment optimization, human capital effect and firm labor productivity. Manag. World 2023, 39, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Symbol | Mean | S.D. | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Corporate greenwashing—difference between standardized environmental, social, and governance disclosure scores and environmental, social, and governance performance scores | gw | −0.038 | 1.190 | Wind Database CSMAR Database |

| Independent Variable | ||||

| Public engagement—number of proposals by NPC deputies and CPPCC members | x | 6.302 | 0.852 | China Environmental Yearbook |

| Intermediary Variable | ||||

| Environmental regulation—ratio of environmental terms in the Government’s annual working report to the total number of terms in the working report | gov | China Environmental Yearbook | ||

| Moderator Variable | ||||

| Organizational inertia—The extent to which the organization’s strategic resourcing fluctuates over annual time frames | str | 0.127 | 0.752 | CSMAR Database |

| Control Variable | ||||

| Year—dummy variable | age | 2.815 | 0.348 | CSMAR Database Wind Database |

| Enterprise size—natural logarithm of the total assets of the enterprise at the end of the period | size | 23.083 | 1.288 | |

| Cash flows—ratio of net profit to total assets | cf | 0.058 | 0.067 | |

| Liability—Total debt to total assets | debt | 0.467 | 0.195 | |

| Tobin Q—Market value divided by the replacement cost of its assets | tobin | 2.017 | 1.320 | |

| SOE dummy = 1 if the firm is state-owned and 0 if not | SOE |

| Mean | sd | age | size | cf | debt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.038 | 1.190 | 1 | |||||||

| 6.302 | 0.852 | −0.072 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 0.127 | 0.752 | 0.098 *** | −0.002 | 1 | |||||

| age | 2.815 | 0.348 | 0.040 *** | −0.017 | −0.019 | 1 | |||

| size | 23.083 | 1.288 | 0.183 *** | −0.130 *** | 0.028 ** | 0.141 *** | 1 | ||

| cf | 0.058 | 0.067 | 0.007 | 0.082 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.025 * | −0.019 | 1 | |

| debt | 0.467 | 0.195 | 0.147 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.038 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.537 *** | −0.246 *** | 1 |

| tobin | 2.017 | 1.320 | −0.068 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.086 *** | −0.087 *** | −0.455 *** | 0.224 *** | −0.438 *** |

| Variable Name | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| −0.095 *** | −0.067 *** | |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| age | 0.204 *** | |

| (0.05) | ||

| size | 0.160 *** | |

| (0.02) | ||

| cf | 0.182 | |

| (0.23) | ||

| debt | 0.465 *** | |

| (0.10) | ||

| tobin | 0.036 *** | |

| (0.01) | ||

| Year-fixed Effect | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed Effect | YES | YES |

| N | 6286 | 6286 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.061 | 0.099 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.042 *** | −0.172 *** | −0.103 *** | |

| (−3.17) | (−2.34) | (−1.22) | |

| age | 0.071 ** | 0.104 | |

| (2.26) | (3.25) | ||

| size | 0.292 *** | 0.328 *** | |

| (29.39) | (28.42) | ||

| cf | 0.303 * | ||

| (3.51) | |||

| debt | −0.422 *** | ||

| (−6.55) | |||

| tobin | 0.009 | ||

| (1.45) | |||

| Year-fixed Effect | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed Effect | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 6286 | 6286 | 6286 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| FEM | Sample Interval | (M4) | (M5) | (M6) | (M7) | Endogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2014 | 2015–2019 | |||||||

| (M1) | (M2) | (M3) | SOE | Non-SOE | High- Polluting | Low- Polluting | (M8) | |

| −0.033 *** | −0.075 *** | −0.117 *** | −0.102 | 0.097 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.183 *** | ||

| (−1.44) | (−2.01) | (−4.36) | (−2.12) | (4.15) | (5.01) | (3.71) | ||

| L.χi, | 0.016 ** | |||||||

| (−2.27) | ||||||||

| age | 0.021 | 0.081 | 0.130 | 0.071 | 0.181 | 0.112 | 0.531 *** | 0.662 |

| (0.18) | (0.01) | (0.11) | (0.54) | (0.65) | (2.21) | (4.34) | (2.49) | |

| size | 0.037 | 0.197 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.311 | 0.532 *** | 0.391 *** | 0.228 *** | 0.543 |

| (0.12) | (3.31) | (1.83) | (0.12) | (0.77) | (4.06) | (1.16) | (2.04) | |

| cf | 0.316 | 0.040 | 0.388 | 0.052 *** | 0.421 | 0.432 *** | 0.229 | 0.074 |

| (1.43) | (1.22) | (0.79) | (3.01) | (0.91) | (3.01) | (0.123) | (3.95) | |

| debt | −0.331 | 0.499 *** | 0.542 | 0.034 | 0.743 | 0.874 | 0.396 *** | 0.483 *** |

| (−2.91) | (3.31) | (0.92) | (0.19) | (0.12) | (0.11) | (4.31) | (2.15) | |

| tobin | 0.004 | 0.001 | 1.021 *** | 0.453 *** | 0.049 | 0.632 | 2.83 *** | 0.191 *** |

| (0.97) | (0.55) | (3.49) | (2.48) | (0.44) | (0.52) | (0.98) | (4.87) | |

| Year-fixed Effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed Effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry-fixed Effect | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City-fixed Effect | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 6286 | 2718 | 3569 | 3211 | 3075 | 4001 | 2285 | 4576 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.091 *** | −0.050 *** | |

| (−16.61) | (−2.88) | |

| age | −0.048 *** | 0.169 *** |

| (−3.25) | (3.81) | |

| size | 0.006 | 0.150 *** |

| (1.29) | (9.80) | |

| cf | 0.048 | 0.054 |

| (0.65) | (0.25) | |

| debt | −0.076 ** | 0.487 *** |

| (−2.49) | (5.27) | |

| tobin | −0.006 | 0.036 *** |

| (−1.58) | (3.12) | |

| −0.023 *** | ||

| (2.67) | ||

| N | 6286 | 6286 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| −0.094 *** | −0.066 *** | |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| 0.104 | 0.123 *** | |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | |

| −0.075 *** | −0.061 *** | |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| age | 0.207 | |

| (0.05) | ||

| size | 0.155 | |

| (0.02) | ||

| cf | 0.203 | |

| (0.23) | ||

| debt | 0.489 *** | |

| (0.11) | ||

| tobin | 0.032 ** | |

| (0.13) | ||

| Year-fixed Effect | YES | YES |

| Firm-fixed Effect | YES | YES |

| N | 6286 | 6286 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.067 | 0.105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; Li, C.; Zhong, Y. Challenging to Change? Examining the Link Between Public Participation and Greenwashing Based on Organizational Inertia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031229

Liu B, Li C, Zhong Y. Challenging to Change? Examining the Link Between Public Participation and Greenwashing Based on Organizational Inertia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(3):1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031229

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Bei, Chengwu Li, and Yin Zhong. 2025. "Challenging to Change? Examining the Link Between Public Participation and Greenwashing Based on Organizational Inertia" Sustainability 17, no. 3: 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031229

APA StyleLiu, B., Li, C., & Zhong, Y. (2025). Challenging to Change? Examining the Link Between Public Participation and Greenwashing Based on Organizational Inertia. Sustainability, 17(3), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031229