European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: Historical Context, Definitions and Research

2.1. Historical Context and Definitions

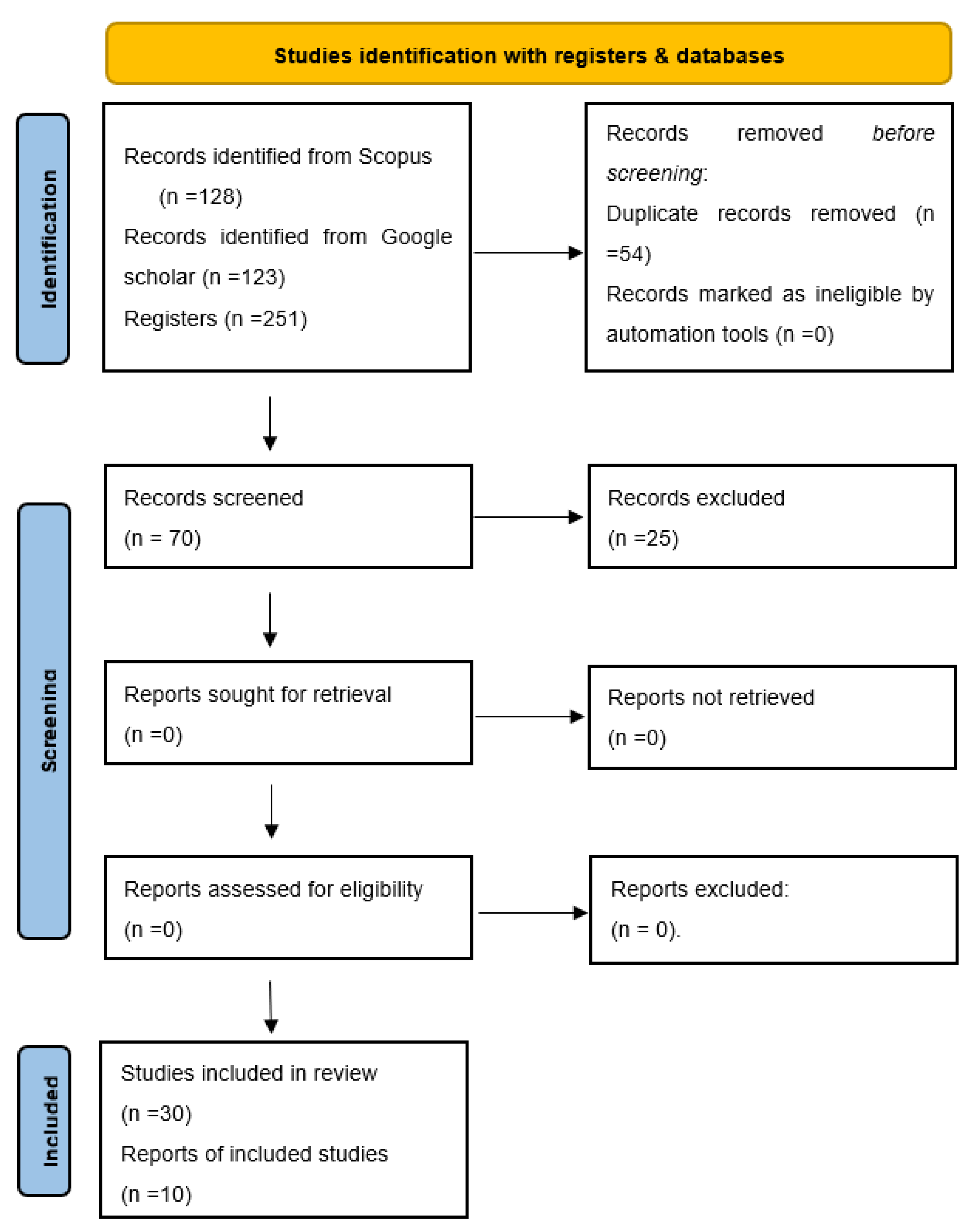

2.2. Current Research

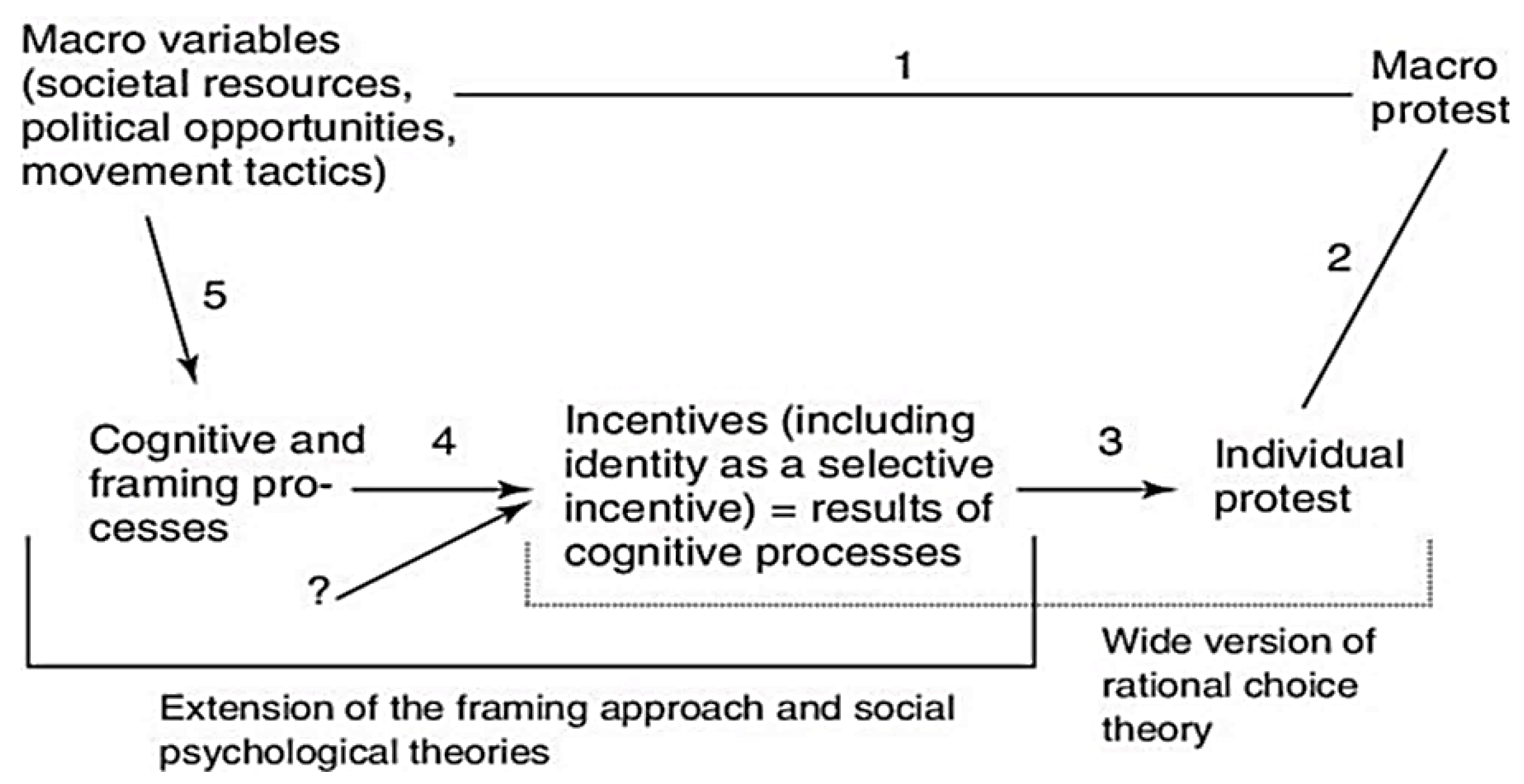

3. Theoretical Framework: The Structural-Cognitive Model (SCM)

3.1. Basic Ideas of the Structural-Cognitive Model

3.2. Macro Perspective

3.3. Micro Perspective

4. Case Study: SCM Applied to the Canary Islands’ Tourismphobia

4.1. Overview Pre-SCM on the Canary Islands Case

4.2. SCM Applied to the Canary Islands’ Tourismphobia

4.3. Relevant Macro Perspective of the Canary Islands Case

4.3.1. Political Opportunity Structures

- -

- Participation in local elections: Local elections offer residents the opportunity to influence policy-making by supporting candidates and parties that prioritize sustainable development and community interests. Although voter turnout in the Canary Islands is often modest, mobilizing voters to support reform-oriented candidates can lead to tangible change. In Lanzarote, for example, members of the local council were elected who supported tourism restrictions after campaigning for stricter regulations on holiday rentals.

- -

- Engaging in public consultations and decision-making processes: Although public consultations in the Canary Islands are often criticized as inadequate, participation in these processes can still provide a platform to voice concerns. Stakeholders can also advocate for more transparency and more frequent consultations. In 2023, for example, activists in Gran Canaria succeeded in delaying the approval of a new hotel complex by overwhelming a public hearing with objections and forcing the planners to revise the proposal.

- -

- Legal action and advocacy: Legal action can be an effective tool for influencing policy. Filing lawsuits or challenging decisions in court has proven successful in other regions facing similar issues. In 2021, a legal challenge by environmental groups delayed the approval of a golf course in Fuerteventura, citing violations of environmental protection laws.

- -

- Grassroots movements: Such movements can influence political decisionmakers and change their decision-making behavior.

- -

- Utilizing social media and digital lobbying: Social media can be used to raise awareness and mobilize support for selected areas of concern, which, in turn, can influence policy makers. The hashtag #StopCunaDelAlma gained a lot of attention and raised awareness of the impact of the planned luxury resort on local communities and the environment [108].

- -

- Education and awareness-raising campaigns: Educating tourists about the environmental, social, and economic impacts of overtourism can be effective. For example, the aforementioned #StopCunaDelAlma campaign in Tenerife made tourists aware of the effects of overtourism [108].

- -

- Protest actions at tourist hotspots: Direct protests at popular tourist destinations can deter tourists and draw attention to local grievances. For example, protests against the construction of new tourist facilities in Gran Canaria have disrupted operations and sent a clear message to tourists about the community’s dissatisfaction with urban sprawl [99].

- -

- Negative reviews on travel platforms: Residents can use platforms, such as TripAdvisor and Google, to highlight the disadvantages of visiting the islands. Negative reviews can shape the perceptions of potential visitors and discourage them from choosing the Canary Islands as a travel destination [109].

- -

- Raising awareness through social media: As previously mentioned, social media campaigns can be an effective tool to sensitize tourists. Hashtags, such as #OvertourismCanaries or #NoMoreHotels, have been used to sensitize both locals and tourists to the pressures of overtourism [110].

- -

- Restriction of tourist services through boycotts: The refusal to provide services to tourists leads to a significant reduction in the quality of the travel destination. In Lanzarote, for example, protests led to the temporary closure of beaches.

- -

- Violent measures: The quality of the travel destination can also be lowered with violent measures, for example against tourist buses and the infrastructure in hotspots of overtourism [110].

4.3.2. Resource Mobilization (RM)

4.4. Relevant Micro Perspective of the Canary Islands Case

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat. Tourism Statistics—Statistics Explained. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tourism_statistics (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Digital transition and readjustmen on EU tourism industry. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2023, 18, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Cerdá, L. Digital Transition, Sustainability and Readjustment on EU Tourism Industry: Economic & Legal Analysis. Law State Telecommun. Rev./Rev. De Direito Estado E Telecomunicacoes 2023, 15, 146–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Sastre, F.J.; Sánchez, L.I. Public management of digitalization into the Spanish tourism services: A heterodox analysis. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellejero, C.; García, J. Historia económica del turismo en España. De los viajeros románticos al pasaporte COVID; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Tragedy of the Commons. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C. Overtourism and Tourismophobia: Global Trends and Local Contexts; Ostelea School of Tourism and Hospitality: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: Global Trends and Local Contexts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 518–532. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C. Overtourism, social unrest and tourismphobia: A controversial debate. Pasos-Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents, and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Renovación del pensamiento económico-empresarial tras la globalización. Bajo Palabra 2020, 24, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; García-Ramos, M.A. A win-win case of CSR 3.0 for wellbeing economics: Digital currencies as a tool to improve the personnel income, the environmental respect & the general wellness. Rev. Estud. Coop.-REVESCO 2021, 138, e75564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Urbina, D.; Alonso-Neira, M.A.; Arpi, R. Problema del conocimiento económico: Revitalización de la disputa del método, análisis heterodoxo y claves de innovación docente. Bajo Palabra 2023, 34, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, D.; Séraphin, H. A systematic literature review and lexicometric analysis on overtourism: Towards an ambidextrous perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; McCabe, S.; Chen, N.C. A socio-psychological conceptualisation of overtourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host Perceptions of Tourism: A Review of the Research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Conceptualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalič, T.; Kuščer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Pellejero, C.; Luque, M. A review of scientific-academic production on tourism in the European Union (2013-23). Iber. J. Hist. Econ. Thought 2024, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M. European historic cities and overtourism—Conflicts and development paths in the light of systematic literature review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. Experiencing Ancient Landscapes. In The Oxford Handbook of Tourism History; online ed.; Zuelow, E.G.E., James, K.J., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, K.M. Medieval Tourism. In The Oxford Handbook of Tourism History; online ed.; Zuelow, E.G.E., James, K.J., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, G. Grand Tour. In The Oxford Handbook of Tourism History; online ed.; Zuelow, E.G.E., James, K.J., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. The evolution of tourism and tourism research. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Yolal, M. Golden age of mass tourism: Its history and development. In Visions for Global Tourism Industry-Creating and Sustaining Competitive Strategies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bagus, P.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Capitalism, COVID-19 and lockdowns. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib.-BEER 2023, 32, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Cultural consumption and entertainment in the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain: Orange economy crisis or review? Vis. Rev. 2021, 8, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rojo, C.; Llopis-Amorós, M.; García-García, J.M. Overtourism and sustainability: A bibliometric study (2018–2021). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Grossling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, J. Critical tourism: Rules and resistance. In The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies; Ateljevic, I., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hajibaba, H.; Gretzel, U.; Leisch, F.; Dolnicar, S. Crisis-resistant tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 53, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, R.; Mantecón, A. The Rise of Anti-Tourism Movements in Spain: Social Movements and the ‘Tourism Degrowth’. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2018, 16, 496–511. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, S.; Alvarez, M. Animosity toward a country in the context of destinations as tourism products. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 1002–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Alvarez, M.; Campo, S. Animosity and perceived risk in conflict-ridden tourist destinations. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Costa, C. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A systematic literature review. Tourism 2020, 68, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, E.M.; Yñiguez, R. Measuring Overtourism: A Necessary Tool for Landscape Planning. Land 2021, 10, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, C.; Szyda, B.; Dubownik, A.; García-Álvarez, D. Airbnb offer in Spain—Spatial analysis of the pattern and determinants of its distribution. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. (Eds.) Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dhiraj, A.; Kumar, S. Overtourism: Causes, Impacts and Solution. In Overtourism as Destination Risk (Tourism Security-Safety and Post Conflict Destinations); Sharma, A., Hassan, A., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V.G.; Thanh, T.V. Between Overtourism and Under Tourism: Impacts, Implications, and Probable Solutions. In Overtourism. Causes, Implications and Solution; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Thanh, T.V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.; Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. Overtourism: A Potential Outcome in Contemporary Tourism—Causes, Solutions, and Management Challenges. In Sustainable Development and Resilience of Tourism; Chhabra, D., Atal, N., Maheshwari, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.M.M.; Martínez, J.M.G.; Fernández, J.A.S. An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of overtourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Silva, M. Residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards future tourism development: A challenge for tourism planners. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M. Tourism and community resilience in the anthropocene: Accentuating temporal overtourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Jeong, Y.; Putri, I.; Kim, S. Sociopsychological aspects of butterfly souvenir purchasing behavior at Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park in Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T.; Bulut, U.; Kocak, E.; Isik, C.; Suess, C.; Sirakaya-Turk, E. The nexus between tourism, economic growth, renewable energy consumption, and carbon dioxide emissions: Contemporary evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 40930–40948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, J.K.S.; Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: Antecedents of destination attractiveness. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinke-Sziva, I.; Smith, M.; Olt, G.; Berezvai, Z. Overtourism and the night-time economy: A case study of Budapest. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E.; Terkenli, T.S. Non-institutionalized forms of tourism accommodation and overtour ism impacts on the landscape: The case of Santorini, Greece. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotopoulos, A.; Pisano, C. Overtourism dystopias and socialist utopias: Towards an urban armature for Dubrovnik. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, P. Selling the rain’, resisting the sale: Resistant identities and the confl ict over tourism in Goa. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2001, 2, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ attitudes towards overtourism from the perspective of tourism impacts and cooperation: The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namberger, P.; Jackisch, S.; Schmude, J.; Karl, M. Overcrowding, overtourism and local level disturbance: How much can Munich handle? Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F. The Perception of Overtourism in Urban Destinations. Empirical Evidence based on Residents’ Emotional Response. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 19, 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Li, L. Understanding visitor–resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Archi, Y.; Benbba, B.; Nizamatdinova, Z.; Issakov, Y.; Vargáné, G.I.; Dávid, L.D. Systematic Literature Review Analysing Smart Tourism Destinations in Context of Sustainable Development: Current Applications and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sard, M.; Valle, E. Tourism degrowth: Quantification of its economic impact. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3786–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z. Reinterpreting activity space in tourism by mapping tourist-resident interactions in populated cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, K.-D. Sociology and Economic Man. Z. Gesamte Staatswiss. 1985, 141, 213–243. [Google Scholar]

- Opp, K.-D. Contending conceptions of the theory of rational action. J. Theor. Politics 1999, 11, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, K. Theories of Political Protest and Social Movements: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, Critique and Synthesis; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Opp, K. Rational Choice Theory and Social Movements. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements; Snow, D.A., Della Porta, D., Klandermans, B., McAdam, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, K. Advanced Introduction to Social Movements and Political Protests; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Opp, K. Methodological Individualism and Micro-Macro Modeling. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methodological Individualism; Bulle, N., Di Iorio, F., Eds.; Palgrave: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume I, pp. 377–405. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger, P.K. The Conditions of Protest Behavior in American Cities. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1973, 67, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.D.; Zald, M.N. Resource Mobilization and Social Movements. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 1212–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; McCarthy, J.D.; Mataic, D.R. The Resource Context of Social Movements. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements; Snow, D.A., Soule, S.A., Kriesi, H., McCammon, H.J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; Strahan & Cadell: London, UK, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A. An Essay on the History of Civil Society; A. Millar & T. Cadell; A. Kincaid & J. Bell: London, UK; Edinburgh, UK, 1766. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, D. A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects; Noon: London, UK, 1739. [Google Scholar]

- Daumann, F. Interessenverbände im politischen Prozeß. Eine Analyse auf Grundlage der Neuen Politischen Ökonomie; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mises, L. The Treatment of “Irrationality” in the Social Sciences. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1944, 4, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mises, L. Human Action. A Treatise on Economics; The Scholar’s Edition; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 1998; [1949]; Available online: https://cdn.mises.org/Human%20Action_3.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Clark, P.B.; Wilson, J.Q. Incentive Systems: A Theory of Organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1961, 6, 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Scarnato, A. “Barcelona in Common”: A New Urban Regime for the 21st-Century Tourist City? J. Urban Aff. 2018, 40, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Overtourism as a Trigger for Tourism Policy Change: The Case of the Barceloneta Neighbourhood, Barcelona. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.; Page, S. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Gestión comparada de empresas colonizadoras del Oeste americano: Una revisión heterodoxa. Retos Rev. Cienc. Adm. Econ. 2022, 12, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Communist origin of American capitalism: Cooperatives in the colonization of the West. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2023, 144, e87973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Ortodoxia versus heterodoxias sobre la colonización del Oeste estadounidense por empresas religiosas e ideológicas. Carthaginensia 2024, 40, 117–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. The Unfinished Agenda: Essays on the Political Economy of Government Policy in Honour of Arthur Seldon; Institute of Economic Affairs: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R. The Nature of the Firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. The problem of Social Cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. The Theory of the Firm as Governance Structure: From Choice to Contract. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de Canarias. Estadísticas (Estadísticas y estudios viejo concepto). 2024. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/turismo/estadisticas_y_estudios/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Instituto Canario de Estadística. Turismo en cifras. 2024. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/estadisticas/sintesis/operacion_C00075B.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Euronews. Multitudinaria Manifestación en Canarias Contra el Turismo Masivo. 2024. Available online: https://es.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/10/20/multitudinaria-manifestacion-en-canarias-contra-el-turismo-masivo-es-un-exceso (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hayek, F. The Fatal conceit; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R. Tourism Restructuring and the Politics of Sustainability: A Critical View from the European Periphery (The Canary Islands). J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 495–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J.V.; Hernández, J.M. Technological heterogeneity and time-varying efficiency of sharing accommodation: Evidence from the Canary Islands. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 111, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Pérez, D. Holiday homes for short-term rental in La Palma (Canary Islands): Evolution and spatial distribution (2015–2020). Cuad. Tur. 2022, 50, 143–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titsa. Informes estadísticos. 2024. Available online: https://Informesestadísticos2023&2024(titsa.com) (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Gobierno de Canarias. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias (Indice >> Memoria 2022 ::: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias). 2022. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs/scs/as/tfe/28/memorias/2022/indice.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Gobierno de Canarias. Contaminación (Contaminación atmosférica). 2024. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/medioambiente/materias/calidad-del-aire/contaminantes-atmosfericos/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hernández Martín, R.; León González, C.; Baute Díaz, N.; Rodríguez González, P.; Marrero Rodríguez, J.R.; Gutiérrez Taño, D.; Santana Turégano, M.A.; Guerra Lombardi, V.; García Altmann, S.; García González, S.; et al. Canary Islands Tourism Sustainability. Progress Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/36905 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Periódico de Canarias. Comunicado de la acampada stop cuna del alma. 2023. Available online: https://www.elperiodicodecanarias.es/comunicado-de-la-acampada-stop-cuna-del-alma/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- TripAdvisor. Reviews for Canary Islands. 2024. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowUserReviews-g187479-r7313853-Tenerife_Canary_Islands.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Manchester Evening News. ‘Forbidden’ Spanish Holiday Destinations. 2024. Available online: https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/trips-and-breaks/travel-guide-names-three-forbidden-30730913 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hidalgo, A.; Riccaboni, M.; Velázquez, F. The effect of short-term rentals on local consumption amenities: Evidence from Madrid. J. Reg. Sci. 2023, 64, 621–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vaquero, M.; Daumann, F.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. European Green Deal, Energy Transition and Greenflation Paradox under Austrian Economics Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G.; Mastini, R.; Zografos, C. Perceptions of degrowth in the European Parliament. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Neira, M.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Spanish Boom-bust Cycle Within the Euro Area: Credit Expansion, Malinvestments & Recession (2002–2014). Politická Ekon. 2024, 72, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Tourism Carrying Capacity Research: A Perspective Article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, A.; Laratte, L. European Green Deal necropolitics: Exploring ‘green’energy transition, degrowth & infrastructural colonization. Political Geogr. 2022, 97, 102640. [Google Scholar]

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S.; Kröger, M.; Dressler, W. From pro-growth and planetary limits to degrowth and decoloniality: An emerging bioeconomy policy and research agenda. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 144, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Essays in Positive Economics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, P. Problems of Methodology: Discussion. Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B. A Critique of Friedman’s Methodological Instrumentalism. South. Econ. J. 1980, 47, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaug, M. Economic Theory in Retrospect; Richard Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Machlup, F. The Problem of Verification in Economics. South. Econ. J. 1955, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. Mathiness in the theory of economic growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Daumann, F. European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031125

Sánchez-Bayón A, Daumann F. European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands. Sustainability. 2025; 17(3):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031125

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Bayón, Antonio, and Frank Daumann. 2025. "European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands" Sustainability 17, no. 3: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031125

APA StyleSánchez-Bayón, A., & Daumann, F. (2025). European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands. Sustainability, 17(3), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031125