3.2. Characteristics of Heavy Metal Pollution in Farmland Soils

As shown in

Table 2, the Cd content ranged from 0.03 to 1.17 mg/kg, with an average value of 0.25 mg/kg. The As content ranged from 1.78 to 45.32 mg/kg, averaging 11.19 mg/kg. The Cr content ranged from 0.05 to 139.50 mg/kg, averaging 64.80 mg/kg. The Hg content ranged from 0.018 to 1.18 mg/kg, with an average of 0.122 mg/kg. The Pb content ranged from 6.81 to 80.06 mg/kg, with an average of 31.80 mg/kg. The soil concentrations of the heavy metals Cd and Hg in China have significantly increased, whereas those of Cr and Pb have decreased, and the As content has remained stable. The pollution severity ranking is Cd > Hg > Pb > Cr > As. Chen et al. [

30] also reached similar conclusions. Compared with the national soil background values, the Cd and Hg concentrations significantly increased, exceeding the background levels by 160.89% and 90%, respectively. Their average soil accumulation indices were 0.80 and 0.34, indicating mild contamination. The Cr and Pb concentrations exceeded the background values by 7.16% and 22.64%, with indices of −0.49 and −0.29, respectively. As exhibited a value of −0.59.

Table A5 presents the current status of heavy metal levels in this study compared with relevant research. Based on sample means, the findings of this study are broadly consistent with domestic research conclusions, both indicating that cadmium and mercury are the primary pollutants requiring urgent remediation [

40].

Compared with international soil heavy metal levels (

Table A5), the average Cd concentration (0.25 mg/kg) in China was lower than those in the United States (0.34 mg/kg and 0.32 mg/kg) and England (0.33 mg/kg), but higher than those in Australia and Europe (0.04 mg/kg and 0.18 mg/kg, respectively). As levels (11.19 mg/kg) and Pb levels (31.80 mg/kg) in China were intermediate between those in Europe (As: 7 mg/kg; Pb: 21 mg/kg) and the more industrialized England (As: 15 mg/kg; Pb: 49 mg/kg). Notably, historical industrial pollution in England has resulted in more severe soil contamination than that in other parts of Europe [

41]. Based on the risk screening values for farmland soils specified in GB 15618-2018 [

42], Cd exceedance rates of 24.66% and Hg exceedance rates of 1.61% were observed in China. The Cd value exceeds global Cd contamination levels in agricultural soils, Hou et al. reported that approximately 9.0% of global agricultural soils exceed the agricultural safety threshold for Cd [

3]. The current stringent soil risk management standards in China significantly overestimate soil heavy metal contamination levels. Taking Cd as an example, China’s standard (0.3 mg/kg) is stricter than those of Russia (0.76 mg/kg) and Finland (1.0 mg/kg) [

43]. However, the soil background levels of Cd in China (

Table 2) are comparable to those in Russia’s Arctic permafrost regions (0.053 mg/kg) and Finland in 1987 (0.123 mg/kg) [

44,

45]. Applying Russian or Finland standards would reduce, China’s soil Cd exceedance rate from 24.66% to 0.90–2.22%. Similarly, China’s Hg standard (0.5 mg/kg) is stricter than those of Sweden and Norway (1.0 mg/kg), despite the background Hg concentration in China (

Table 2) being close to those in central Norway (approximately 0.06 mg/kg) [

43,

46]. Adoption of the Norway’s standard would reduce Hg exceedance rates from 1.61% to 0.54%. For other elements such as As and Pb, despite the similar soil background values to Japan, China’s regulatory standards (As: 30 mg/kg, Pb: 80 mg/kg) are significantly stricter than Japan’s (As: 150 mg/kg, Pb: 150 mg/kg) [

43,

47]. Those comparisons indicates that the relatively high exceedance rates of soil pollutants in China are largely attributable to the stringency of its regulatory standards. The underlying reasons for these divergent international standards are complex and often rooted in differences in soil environmental background values, land use patterns, and national risk assessment frameworks. Soil background values, which are influenced by regional geology and pedogenesis, form the natural baseline for contamination assessment. While this study notes comparable background levels for some elements between China and certain other regions, the integration of these baseline levels into health-based standards varies. Furthermore, land use types critically determine exposure pathways and risk scenarios [

48]. Therefore, China’s stringent standards likely reflect a precautionary approach, synthesizing its specific environmental background, intensive land use, and public health priorities. This contextual understanding strengthens the scientific basis for policy recommendations, suggesting that while international benchmarking is informative, soil management policies must be tailored to national and regional circumstances.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the heavy metal concentrations in the soils of agricultural land (mg/kg).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the heavy metal concentrations in the soils of agricultural land (mg/kg).

| Heavy Metal | As | Cd | Cr | Hg | Pb |

|---|

| Number of samples 1 | 235,643 | 248,386 | 219,834 | 229,085 | 239,561 |

| Max 1 | 45.32 | 1.17 | 139.50 | 1.18 | 80.06 |

| Min 1 | 1.78 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.018 | 6.81 |

| Mean 1 | 11.19 | 0.25 | 64.80 | 0.122 | 31.80 |

| Igeo | −0.59 | 0.80 | −0.49 | 0.34 | −0.29 |

| Number of outliers | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| Background value 2 | 11.20 | 0.097 | 61.00 | 0.065 | 26.00 |

| Standard value 3 | 30.00 | 0.30 | 250.00 | 0.50 | 80.00 |

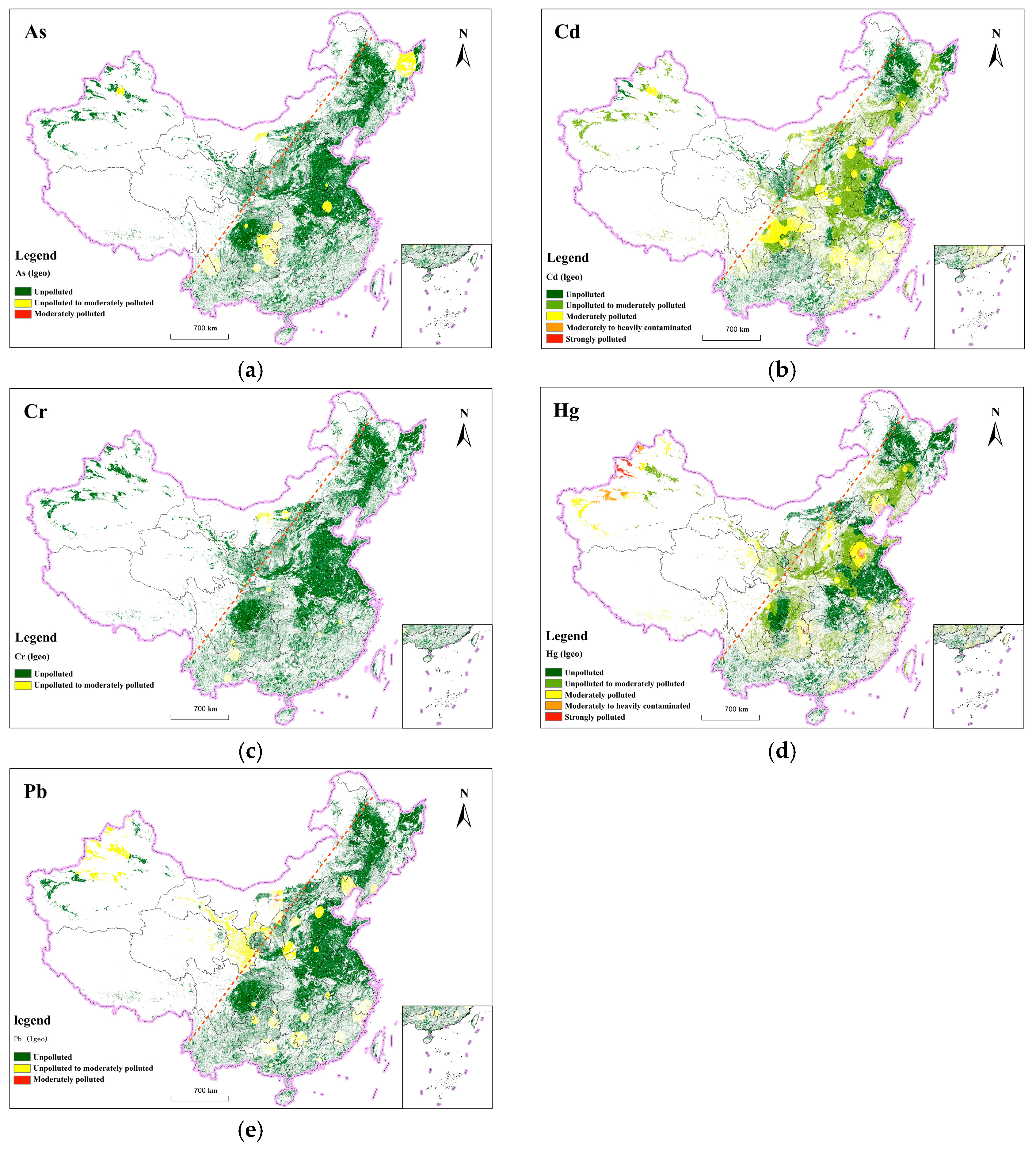

3.4. Spatial and Temporal Trends of Heavy Metal Pollution in Farmland Soils

The geoaccumulation index for the five heavy metals exhibited distinct temporal patterns between 2003 and 2025 (

Figure 4). The

value for As remained negative, indicating an unpolluted state, but it showed an upward trend. In contrast, the

values for Cd and Hg were positive and demonstrated a clear upward trajectory over the study period, although the rate of increase appeared to slow after approximately 2017. This attenuation is likely attributable to the implementation of stringent environmental policies—such as the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan—which have effectively reduced anthropogenic inputs of heavy metals into agricultural soils. The

for Cr fluctuated within a narrow range between −1.0 and −0.5, showing no significant trend, possibly reflecting its dominant natural origin and limited anthropogenic influence. The

for Pb increased from 2003 to around 2015, after which it began a marked decline, a reversal that coincides with the nationwide phase-out of leaded gasoline and enhanced industrial emission controls. Overall, the changes in concentration for these five heavy metals over the past two decades have been relatively modest. At the national scale, heavy metal pollution in China’s farmland soils remains generally mild, and the previously observed increasing trend has been preliminarily curbed. This improvement is likely attributable to the implementation of stringent environmental policies which have effectively reduced heavy metal inputs into agricultural soils. The findings of [

11,

40] also reported a decreasing trend of increasing Cd and Hg pollution in China in the past decade.

While the strict standards present a statistical challenge, they have been paralleled by a suite of aggressive policies that have successfully curbed the escalating trend of heavy metal pollution over the past decade. The escalating trend of heavy metal mercury and cadmium contamination in Chinese soils has been curbed. Compared with the 2006–2015 period, the comprehensive phase-out of leaded gasoline in 2000 and stringent post-2010 emission standards for lead and zinc industrial pollutants resulted in a 43.62% reduction in atmospheric Pb emissions during 2015–2020 [

51]. Since 2012, China has implemented stringent industrial emission standards and fulfilled its obligations under the Minamata Convention on Mercury, which prompted multipollutant synergistic ultralow emission retrofits in coal-fired power plants, nonferrous metals, and cement industries, as well as the phased closure of primary mercury mines (except for special purposes). As a consequence, compared with the 2006–2015 period, atmospheric Hg emissions decreased by approximately 63.87% during 2015–2020 [

51]. Following the nationwide ban on sewage irrigation in 2013, agricultural irrigation has relied primarily on surface runoff and groundwater. Since the implementation of the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan in 2015, the proportion of surface water sections meeting Class I–III standards nationwide has increased from 67.8% in 2016 to 89.4% in 2023, representing a 21.6% improvement, whereas the proportion of Class V or lower sections declined from 8.6% to 0.7% (a reduction of 7.9%). Heavy metal concentrations in surface water decreased by 1 to 19 times [

52], reducing soil heavy metal inputs from irrigation water. China launched the “Zero Growth in Fertilizer Use Action” in 2015. By 2024, application rates of phosphate, nitrogen, and potassium fertilizers had decreased by 33%, 31%, and 14.7%, respectively, compared with the 2009 levels (

Figure A2). Fertilizer registration and management measures have imposed strict controls on the heavy metal content in registered fertilizer products, thereby reducing fertilizer-derived inputs of certain heavy metals. Furthermore, continuous improvements in fertilization techniques and advances in production processes have also decreased heavy metal contributions from fertilizers. In 2017, the Hygiene Standard for Feeds (GB13078-2017) [

53] systematically established maximum allowable limits for heavy metals, including Pb, Hg, As, Cd, and Cr in livestock, for the first time, effectively reducing heavy metal concentration in manure. Between 2015 and 2020, relative to 2006–2015, total inputs of As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb from livestock manure decreased by 9.90%, 32.76%, 9.03%, 30.77%, and 18.49%, respectively [

51]. However, the current Limit Requirements of Toxic and Harmful Substance in Fertilizers (GB 38400-2019) [

54] still set higher thresholds for Cd and Hg than the soil pollution risk screening values defined in GB 15618-2018 [

50], implying that fertilizer application remains a potential source of soil heavy metal contamination. In 2016, the State Council issued the Action Plan for Soil Pollution Prevention and Control, establishing the first comprehensive institutional framework for soil pollution management in China. This initiative has played a fundamental, systematic, and transformative role in reversing the trend of soil pollution deterioration.

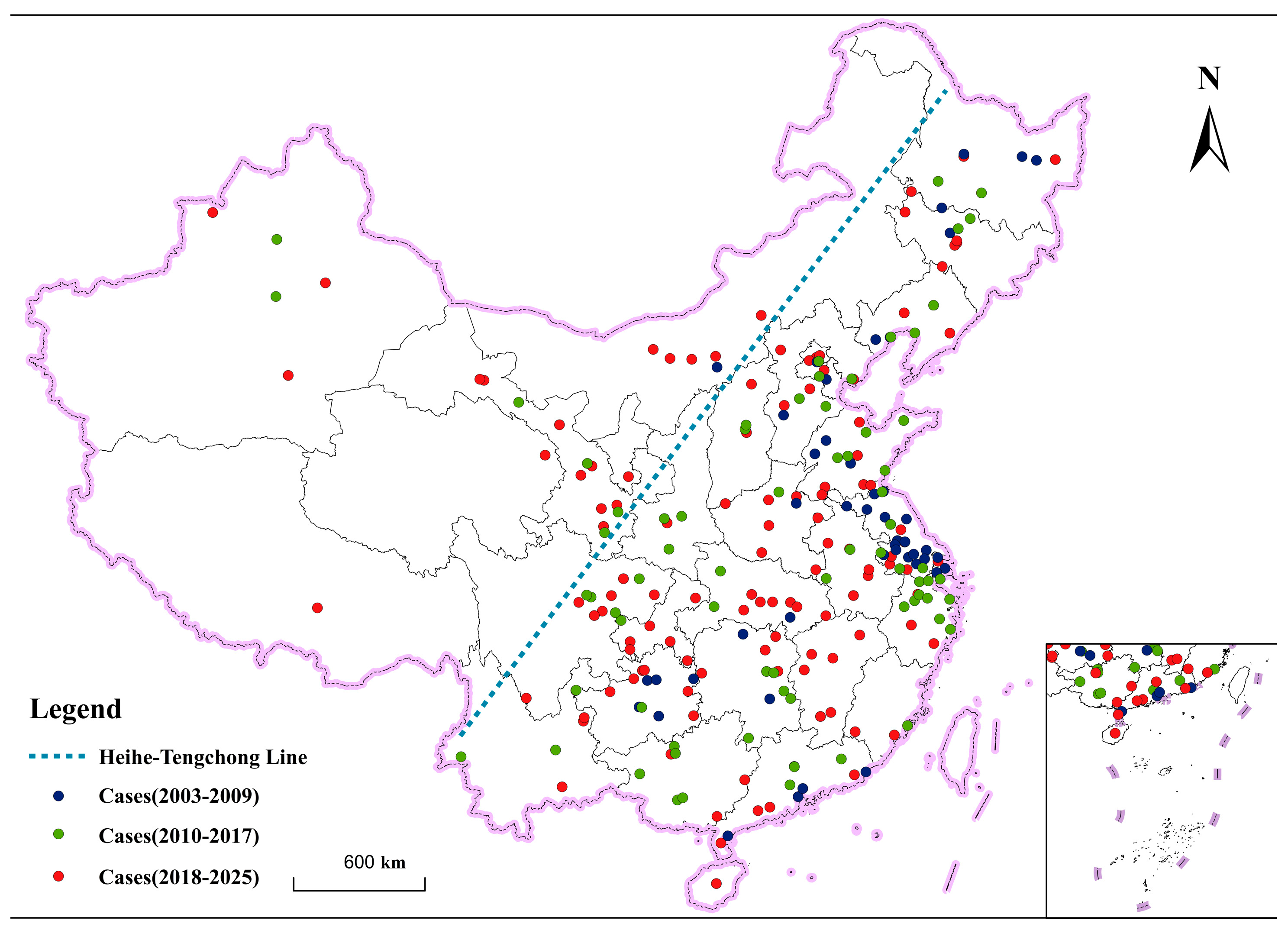

The spatial evolution patterns of the five heavy metals in Chinese farmland soils across the three periods, as revealed by the SDE analysis, are shown in

Figure 3. In Phase I, the 48 cases recorded exhibited a north-south axial banded distribution, with most cases located in eastern provinces and the SDE rotation angle was 19.32°. In Phase II, the number of cases increased to 75, forming a dual-core spatial pattern with expansion in the both the eastern coastal regions (Hebei, Zhejiang) and the central–southern inland areas (Hunan, Guangxi). During this phase, the SDE rotation angle reached 93.27°, predominantly oriented “east (slightly south) and west (slightly north)”. The SDE gradually shifted along a northeast-southwest axis, with its centroid moving westward by 3.67° in longitude from east to southwest. The east-west standard distance increased, with many cases distributed within the ellipse, indicating higher spatial density of heavy metal occurrences. In Phase III, the number of cases further increased to 121. The SDE major axis (12.51) and minor axis (7.2) expanded by 4.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with phase I and phase II. The SDE rotation angle increased to 109.87°, with its major axis oriented along the northeast–southwest direction and the centroid continued to drift westward 3.74° in longitude. Over the past two decades, the SDE centroid has shifted from the eastern coastal regions toward the western inland areas, accompanied by an expanding spatial distribution and heightened dispersion. This migration pattern aligns with the evolution of China’s economic landscape. Over the past decade, the central and southwestern regions have progressively emerged as the nation’s fastest-growing economic zones. From 2013 to 2023, the annual average growth rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the central and western regions (LP, YR, SB, YGP, QTP, NAR) stood at 7.66%, exceeding that of the eastern regions (EC, NR, HP, SC) by 0.94 percentage points [

55]. Ren and Yang also reached similar conclusions [

40,

56].

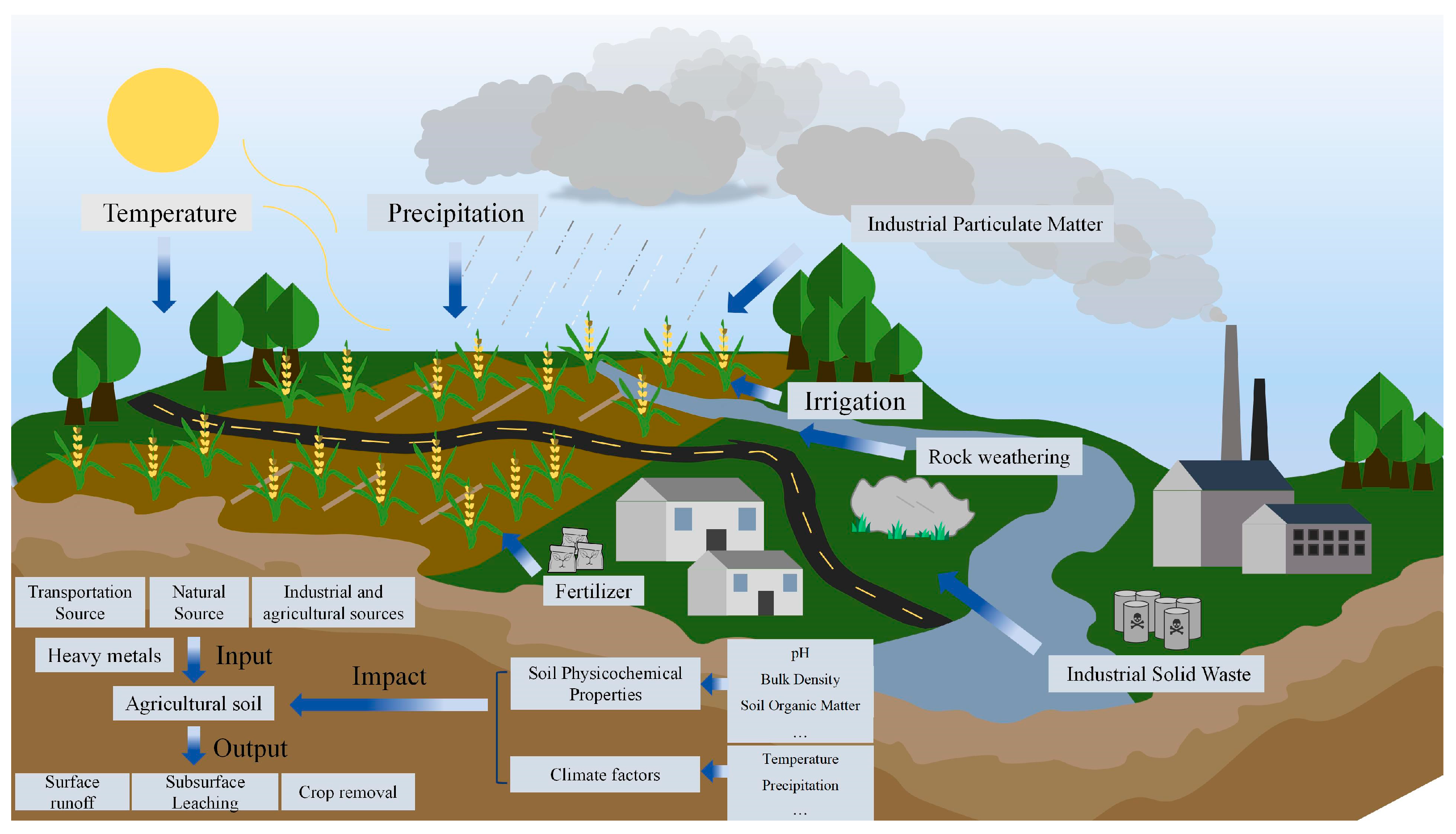

3.5. The Drivers of Potentially Toxic Elements Pollution in Farmland Soils

Figure 5 illustrates the primary drivers for five heavy metals, with varying contributions from different influencing factors across the five heavy metals. The primary influencing factors for As were identified as Average Comprehensive Utilization Rate of Industrial Solid Waste (ACURISW), Average Per Capita GDP (APCGDP), Average Output Value of Primary Industry (AOVSI), Fertilizer, and Average Wind Speed (AWS). For Cd, the dominant factors included Soil Organic Matter (SOM), AWS, Total Nitrogen (TN), Irrigation, and Total Volume of Non-Compliant Industrial Wastewater Discharge (TVNCIWD). The key factors affecting Cr were Average Temperature (AT), Average Humidity (AH), Total Volume of Industrial Wastewater Discharge (TVIWD), Average Precipitation (APR), and AWS. In the case of Hg, the major influencing factors were TVIWD, pH, AH, Clay, and SOM. Regarding Pb, the most significant factors were pH, Clay, APR, AT, Available Phosphorus (AP), and SOM.

When interpreted in conjunction with existing literature on Chinese agricultural soils, our findings underscore the combined influence of climatic conditions and soil physicochemical properties on heavy metal distribution, with the exception of arsenic. For As, the model places greater emphasis on socio-economic and industrial indicators (e.g., ACURISW, APCGDP), aligning with mounting evidence linking arsenic accumulation to anthropogenic activities [

2]. For the remaining heavy metals (Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb), our results strongly support established consensus. For the heavy metals examined in this study (Hg, Cr, Pb, Cd), environmental behavior is predominantly governed by the interaction between soil physicochemical properties (e.g., pH, SOM) and climatic factors (e.g., AWS, AT, AH), which collectively form a key integrated driving framework [

57,

58]. Notably, for Hg, the combined influence of industrial sources (TVIWD) and soil pH highlights a typical scenario where pollutant emissions interact with soil geochemical conditions to determine final accumulation. This nuance refines the purely industrial emission source previously emphasized by Song [

15].

The R

2 values for As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb were 0.60, 0.61, 0.81, 0.85, and 0.60, respectively. These results indicate that the models for Cr and Hg explained over 80% of the spatial variance, demonstrating high reliability. The models for As, Cd, and Pb, while slightly lower, still accounted for approximately 60% of the variance, which is considered acceptable for complex environmental systems. The corresponding RMSE values (As: 2.97, Cd: 0.09, Cr: 8.09, Hg: 0.04, Pb: 7.80) provide context for the average prediction error relative to the actual concentration ranges. The slightly lower but still acceptable R

2 for As, Cd, and Pb (around 0.60) indicates that while our model captured the major influencing factors, there might be additional localized or unmeasured sources contributing to their variability. This favorable model performance underpins the credibility of the subsequent spatial distribution and driver analysis (

Figure 6).

Broadly, the key drivers can be summarized as follows: anthropogenic activities play a dominant role in governing As accumulation while also exerting a partial yet significant influence on Cd and Hg. In contrast, Cr is primarily controlled by climatic conditions, and Hg and Pb are mainly regulated by soil physicochemical properties. Importantly, the environmental behavior of multiple heavy metals—particularly Hg, Cr, Pb, and Cd—is jointly shaped by the interactive effects of climatic factors and soil properties, highlighting the complexity of their driving mechanisms. This categorization provides a structured framework for discussing the underlying processes, which are elaborated in the subsequent sections according to these three factor categories.

Among anthropogenic factors, Cd accumulation is affected primarily by the irrigation volume, the discharge of noncompliant industrial wastewater, and fertilizer application rates. Owing to a 56-year history of sewage irrigation, heavy metal-contaminated areas accounting for 65% of the total sewage-irrigated land area, with Hg and Cd being the most severe contaminants [

59]. Although sewage irrigation was officially banned in 2013, sporadic practices persists in several northern regions (e.g., the HP) [

60]. Excessive irrigation further intensifies leaching, enhancing the downward migration of heavy metals into deeper soil and groundwater, thereby increasing the risks of secondary pollution diffusion [

61]. In agriculture system, phosphate fertilizers are a major pathway for Cd and As, as these elements present as impurities in phosphate rock [

29]. Moreover, excessive nitrogen fertilizer application decreases soil pH, creating acidic conditions that enhance heavy metal dissolution, migration and bioavailability [

62]. This effect is particularly obvious in the major grain-producing and fertilizer-intensive regions such as HP, SB, YR, and SC [

63,

64], which account for 14.7%, 8.7%, 14%, and 7.3% of the national phosphorus fertilizer consumption and 21.5%, 7.3%, 15%, and 7.4% of the nitrogen fertilizer application, respectively [

55]. Industrial solid waste utilization rates, per capita GDP, and fertilization practices significantly affect soil As concentration. Consequently, industrial zones and intensive farmed regions (e.g., HPs and YRs) may represent potential hotspots of arsenic accumulation.

Climate factors (temperature, wind speed, humidity, and precipitation) and soil physicochemical properties (pH, clay content, and soil organic matter (SOM)) jointly control the environmental behavior of heavy metals (Hg, Cr, Pb, and Cd), with significant interactions between these two categories of drivers. In terms of climate, elevated temperatures enhance the solubility and mobility of heavy metals in environmental media [

65] and accelerate the SOM decomposition, thereby altering metals-binding forms and stability [

66], which can lead to the release of previously bound metals or the formation of more stable organo-metal complexes, depending on the specific metal and soil conditions [

67]. Moreover, increased temperature can stimulate microbial activity, which consumes oxygen and lowers the redox potential (Eh) in soil microsites [

68,

69]. This shift towards anaerobic conditions can promote the reductive dissolution of iron and manganese (oxyhydr) oxides, thereby releasing associated heavy metals such as As and Cd into the soil solution [

69]. further indicated that heavy metal contamination is more severe in subtropical monsoon climate zones than in colder, humid subnorthern climate zones. It does this firstly through leaching, which lowers soil pH and enhances metal desorption from clay particles. Secondly, the resulting water saturation alters the soil’s redox state, triggering the reductive dissolution of iron and manganese oxides and the subsequent release of their associated heavy metals. These processes work in tandem to drive the desorption and remigration of heavy metals, ultimately controlling their vertical and lateral redistribution [

70,

71,

72].

This mechanism is obvious in southern regions with high rainfall, especially in southwestern China, where extreme weather events are becoming more frequent [

34]. Humidity also affects heavy metal mobility within the soil–plant system by altering evaporation pathways [

73]. Wind speed primarily affects heavy metal redistribution and deposition: high-speed winds from uncontaminated directions typically dilute and remove pollutants, reducing soil contamination from atmospheric deposition, whereas low-speed or calm winds may cause pollutant accumulation and deposition, increasing soil heavy metal input and accumulation [

74]. With respect to soil physicochemical properties, the soil pH affects the dissolution/precipitation equilibrium and adsorption behavior of heavy metals, whereas the adsorption rate is affected by factors such as precipitation and fertilization. Increased clay concentration increases soil adsorption and immobilization of heavy metal ions, reducing leaching losses and facilitating accumulation in surface soils [

75,

76,

77]. SOM adsorbs heavy metals through complexation [

78], but its stability is also affected by factors such as temperature and pH.

Compared with anthropogenic influences, climatic factors and soil physicochemical properties are the main drivers affecting the spatial distribution and accumulation of multiple heavy metals. This process essentially involves complex source–sink relationships and migration pathways (

Figure 7). For example, climatic factors not only directly affect the migration and transformation of heavy metals but also indirectly affect their fate by altering critical soil properties. In the context of global climate change, rising temperatures and frequent extreme precipitation events may significantly alter regional soil environments, further disrupting heavy metal stability and elevating their ecological risks, ultimately posing threats to agricultural environmental safety [

79,

80,

81]. With respect to Cd, the high-risk regions in China—such as the SB, SC, and YR—are located within the subtropical monsoon climate zone. The combination of elevated-temperatures and abundant rainfall not only increase weathering and the release of metals from parent materials but also facilitate Cd accumulation in surface soils by affecting SOM decomposition and the adsorption-desorption behavior of clay particles [

3]. Therefore, it is recommended that future research systematically investigate the environmental behavior and ecological risks of heavy metals in the context of climate change, providing theoretical support for the formulation of strategies aimed at preventing and controlling food security risks.