Optimization of a Passive Solar Heating System for Rural Household Toilets in Cold Regions Using TRNSYS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Objects and Methodology

2.1. Research Objects

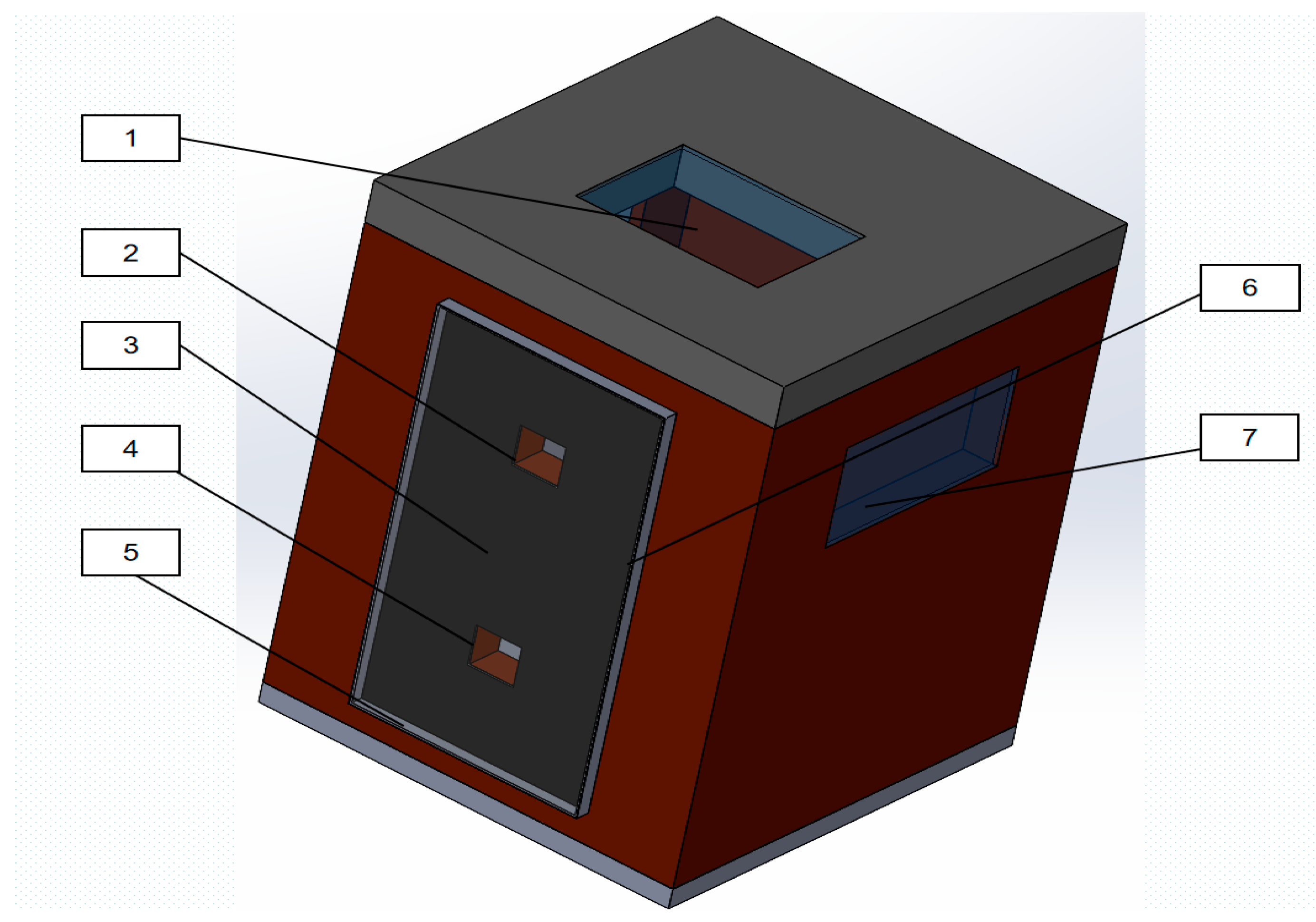

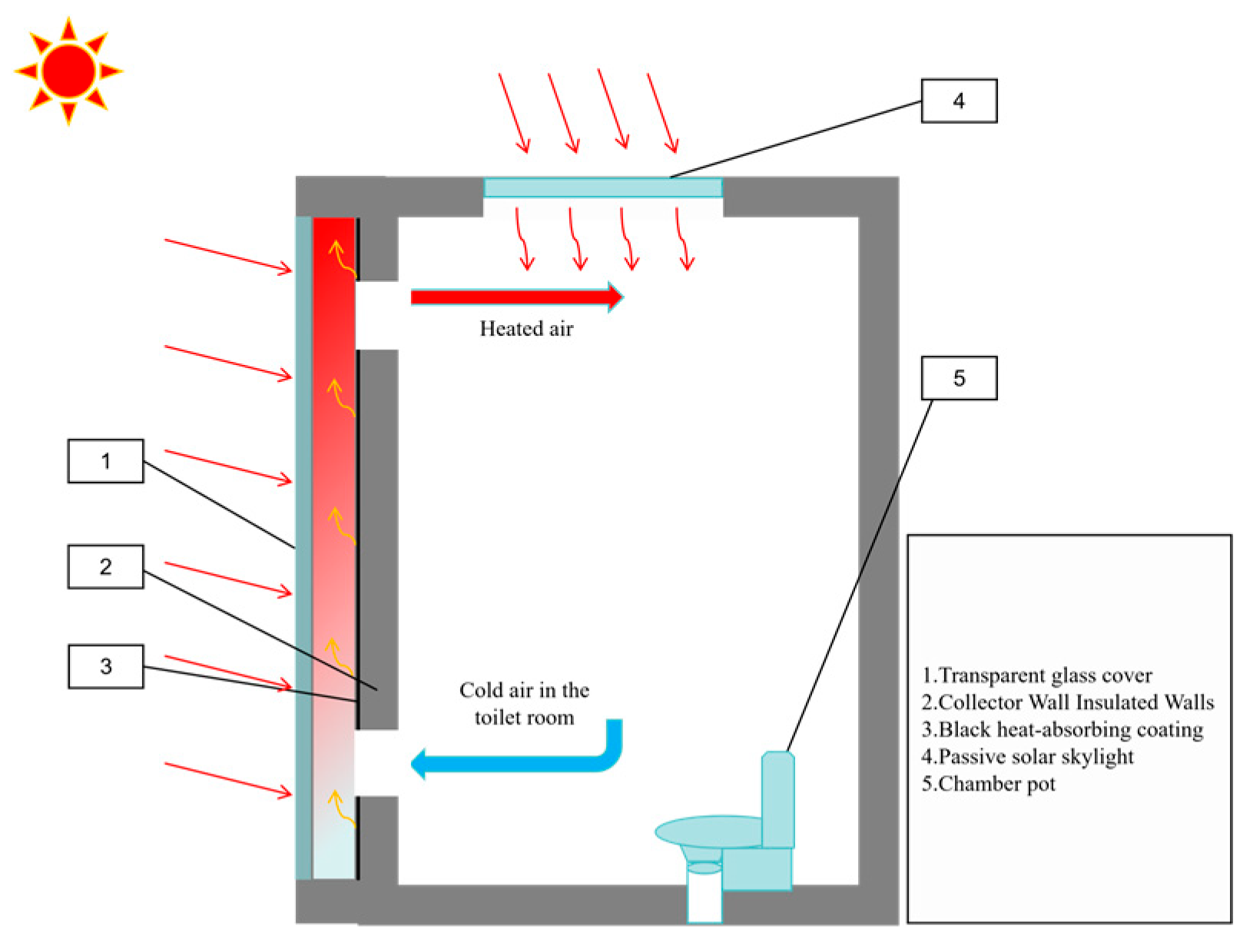

2.1.1. Passive Toilet Cabin

2.1.2. Passive Solar Heating System

2.2. Experimental Methodology

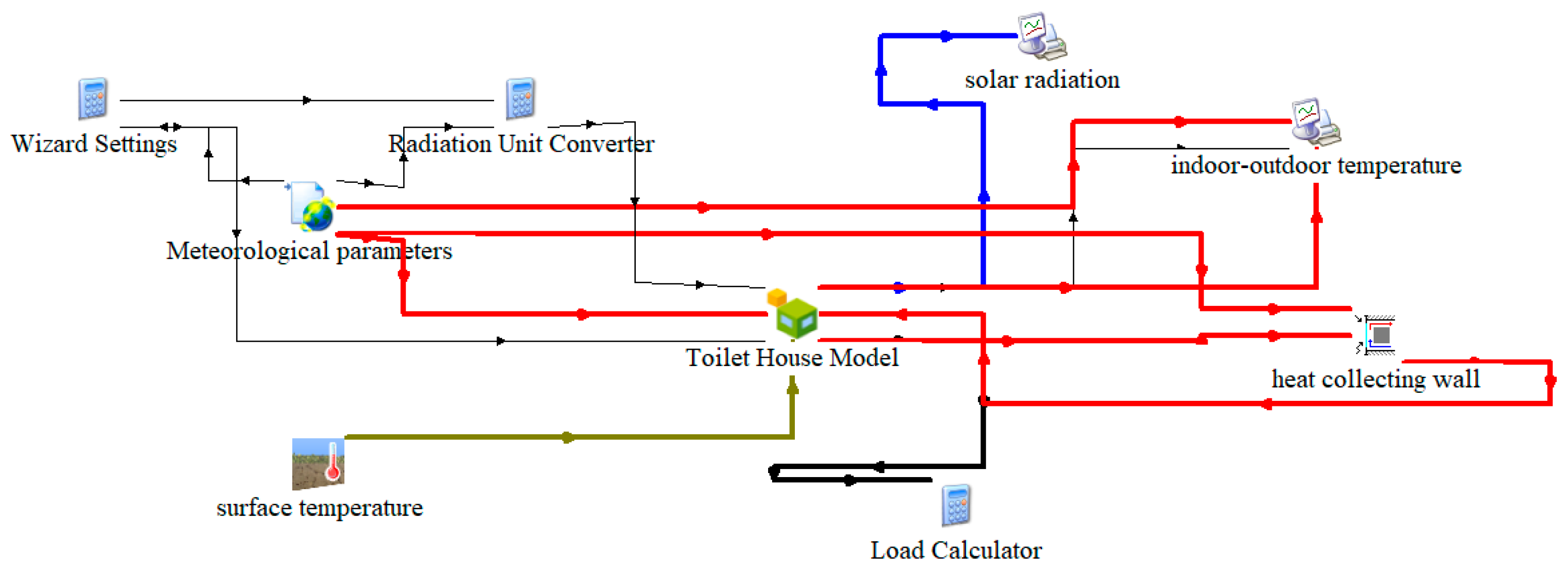

2.2.1. TRNSYS Simulation Modeling

- (1)

- Model Development

- (2)

- Thermodynamic Simulation Framework

2.2.2. Key Factor Screening Experiment

2.2.3. Optimal Parameterization Experiment

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Key Factor Screening

3.2. Optimal Parameters of Key Factors

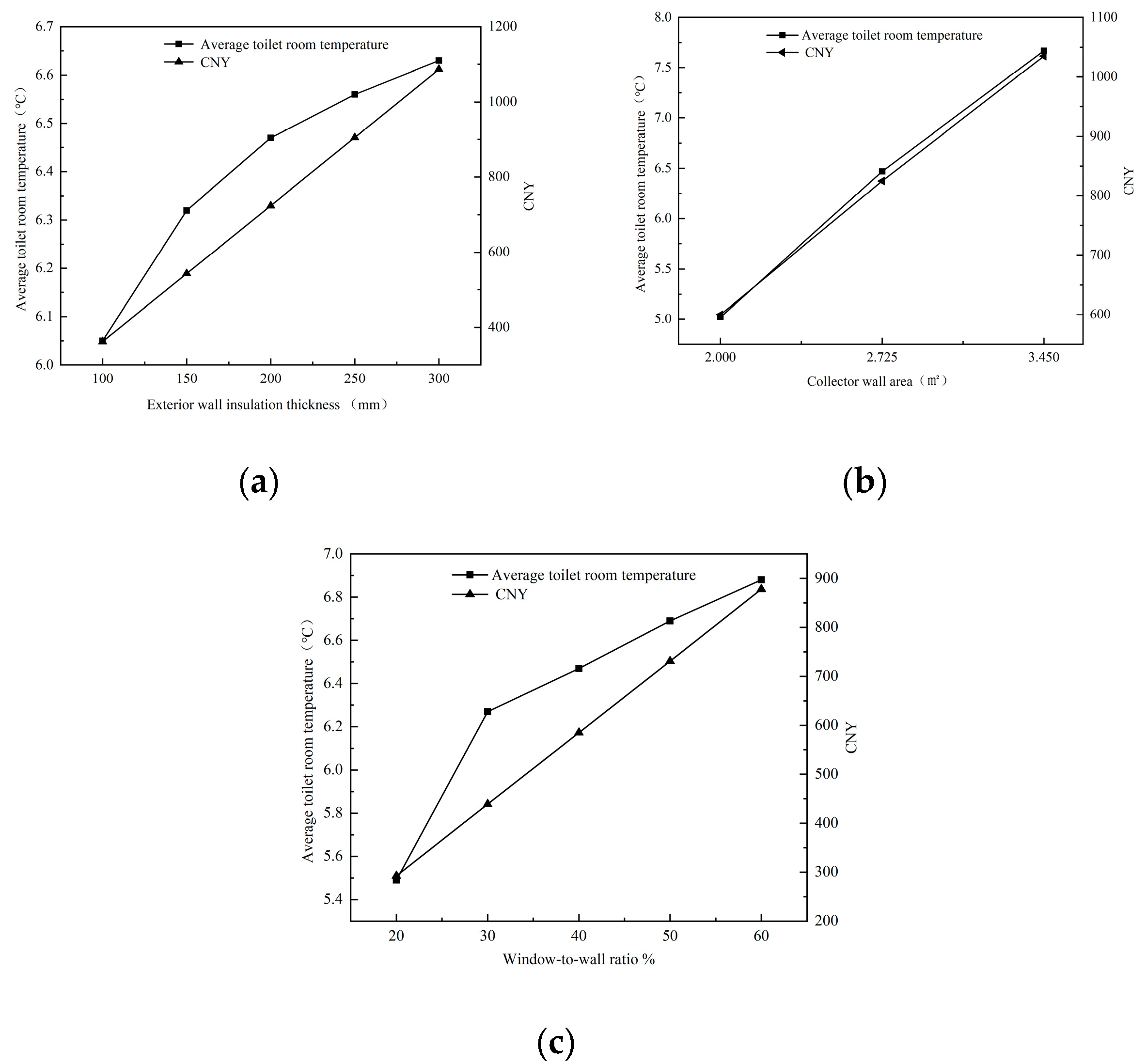

3.2.1. Optimal Parameter Determination of Exterior Wall Insulation Thickness (A), Collector Wall Area (D), and Window-to-Wall Ratio (C) of the Toilet House

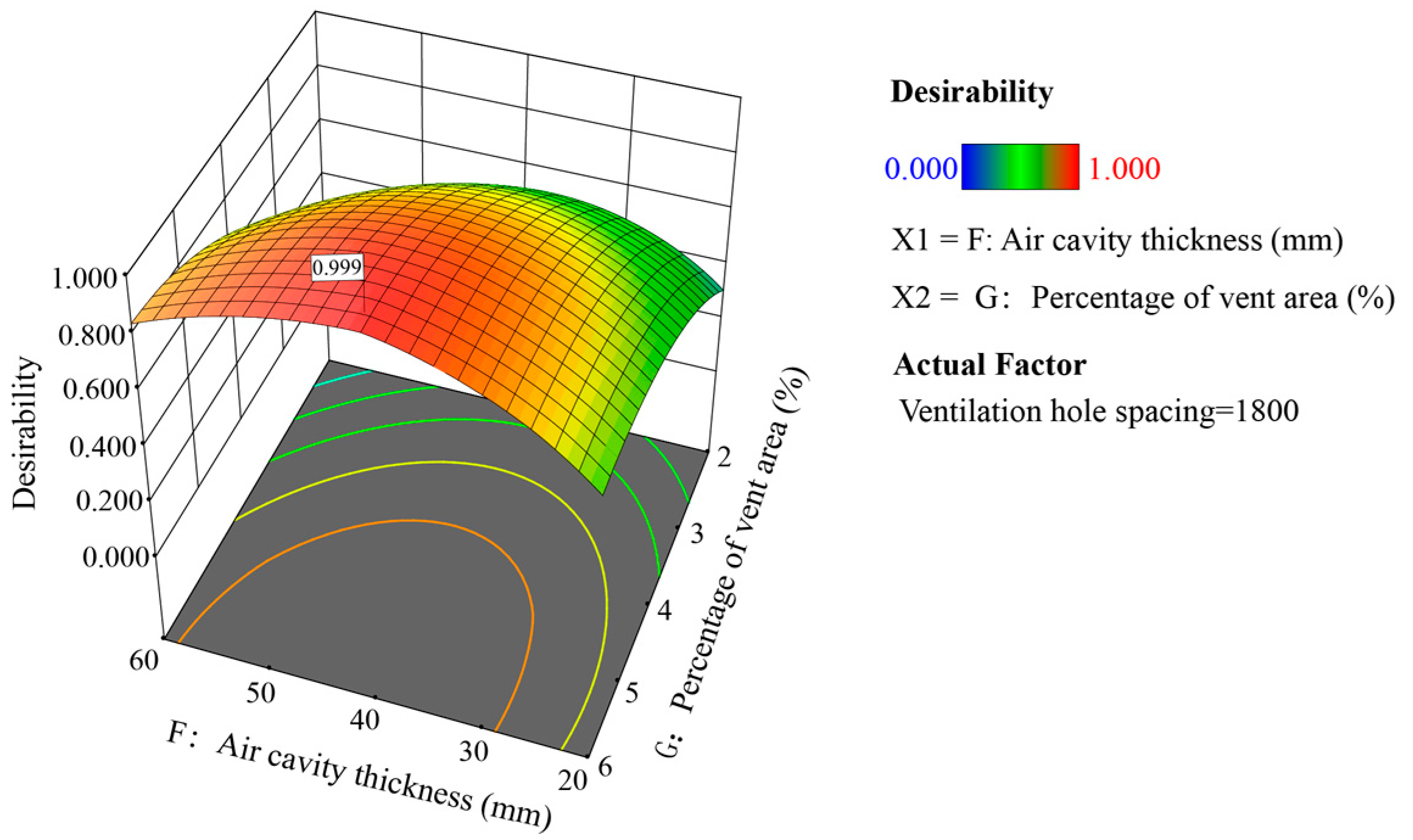

3.2.2. Optimal Parameter Determination of Vent Spacing (E), Air Cavity Thickness (F), and Vent Area Ratio (G) of the Solar Collector Wall

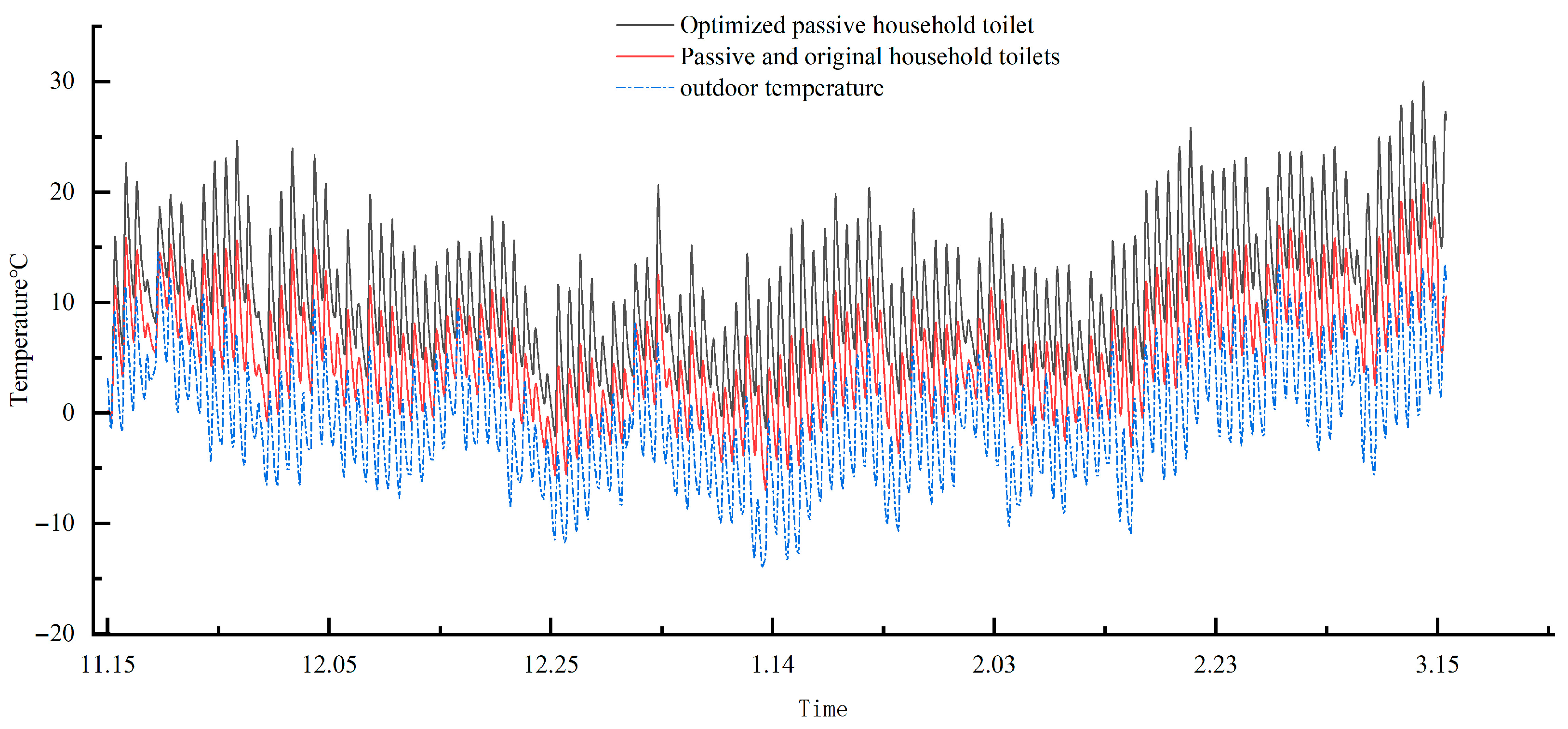

3.3. Comprehensive Performance of Optimized Passive Solar Toilet System

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence Mechanism of Key Parameters on the Thermal Environment of Toilet Houses

4.2. Multi-Parameter Synergistic Effect of the Passive Solar Heating System

4.3. Long-Term Feasibility of the Optimized Passive Solar Heating System

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Practical implications: The extra cost per toilet of CNY 800–1200 fits national subsidies (CNY 1000–3000 per household); widely available components (XPS insulation, aluminum absorber plates) and simple installation suit rural construction capacity. It can be scaled to other cold regions (e.g., 10–15% larger solar walls in Heilongjiang), supporting China’s rural sanitation plans and carbon goals.

- (2)

- Future research: Integrate passive heating with low-cost thermal storage (e.g., PCMs in air cavities) to cut subzero hours; use CMIP6 data to optimize for climate change; and conduct rural field trials to refine user-centric designs (e.g., detachable collector walls), boosting adoption.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Statistics Division. Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/Goal-06/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- United Nations. Ensure Safe and Hygienic Sanitation for All, UN Urges, Marking World Toilet Day. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/11/1078032 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- World Bank; Global Water Security & Sanitation Partnership (GWSP). 2025 Global Sanitation Crisis: Emergency Action Pathways. Available online: https://m.sohu.com/a/942605847_121833998 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); Jomoo Group. Technology Innovation Empowers Toilet Revolution: Contributing to Global Sustainable Development. Available online: https://m.toutiao.com/group/7339821371268203047/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Ma, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, T. Current situation and technical progress of rural latrine reform in the cold and arid region of northwest China:a case study of Gansu Province. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2025, 42, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, P.; Gao, Y.; Tan, L.; Peng, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, X. Reference for technology models and management mechanisms of toilets in dry and cold regions abroad. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2023, 40, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J. Investigation and Solutions to Winter Anti-Freezing Problems in Rural Dry Toilet Renovation. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2018, 16, 92–93+95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Hua, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, X.; Luo, L. Establishment of an index system for evaluating technical models adapted for rural toilet renovation in cold and arid regions. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2023, 40, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.A.; Imghoure, O.; Tittelein, P.; Belouaggadia, N.; Chehade, F.H.; Sebaibi, N.; Lassue, S.; Zalewski, L. Application of Ventilated Solar Façades to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings: A comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1266–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, S.A.M.; Li, X. Evaluating the feasibility and challenges of using passive solar systems for achieving thermal comfort in African countries: A review. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Current Status of Passive Solar Heating Buildings. Agric. Technol. 2021, 41, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, S.; Jiang, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Simulation of the thermal performance of a Trombe wall in winter using computational fluid dynamics. Sichuan Build. Sci. 2018, 44, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Che, R.; Zhou, L. Optimization design of active and passive solar combined heating in Lhasa based on zero energy consumption constraint. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 53, 811–818, +834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, H.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Arici, M.; Li, D.; Luo, D.; Jia, J.; Jiang, W.; Qi, H. Evaluation of energy-saving retrofits for sunspace of rural residential buildings based on orthogonal experiment and entropy weight method. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 70, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ma, L.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Qi, H.; Liu, Y. Energy-Saving Retrofits of Prefabricated House Roof in Severe Cold Area. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 254, 124455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z. Study on Improving Effect of Solar Heating on Rural Toilet Thermal Environment in Qinghai Area. Master’s Thesis, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Feng, Y.; Gu, J.; Gao, Q. Dynamic analysis on the thermal parameters of direct gain solar building. Renew. Energy Resour. 2010, 28, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yongheng, D.; Guohua, W.; Xucan, S.; Junchao, Z.; Zhongtao, Z. Research on Multi-Energy Sequential Complementary Heating System Based on TRNSYS Simulation. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yan, L.; Yi, W.; Jia, L. Measurement and Evaluation of Indoor Thermal Environment of Residential Buildings in Lhasa in Winter. Build. Sci. 2011, 27, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ju, Z.; Tian, H.; Liu, Y.; Arici, M.; Tang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Qi, H. Net-zero energy retrofit of rural house in severe cold region based on passive insulation and BAPV technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Study on Thermal Efficiency of Large-Scale Flat Plate Solar Collectors. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2021, 42, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, L. Collaborative Optimization Design of Building Thermal Insulation and Solar Heat Collection Area of Residential Buildings in Lhasa. J. BEE 2023, 51, 36–41+61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Research on Thermal Environment Improvement and Energy Conservation of Rural Toilets with Active and Passive Solar Energy in Qinghai. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10009-1023683781.htm (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- GB/T 10801.1-2021; Moulded Polystyrene Foam Board for Thermal Insulation (EPS). State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: http://c.gb688.cn/bzgk/gb/showGb?type=online&hcno=09AF800545D952238FCD2EA8CB71EBCE (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Name | Material | Heat Transfer Coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | Specific Heat Capacity [kJ/(kg·K)]· |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Envelope structure of the toilet house | Roof assembly: 20 mm fiberboard + 50 mm XPS insulation + 20 mm corrugated sheet | 0.30 | - | - |

| Roof glazing: Thermally broken aluminum frame window | 1.30 | |||

| Wall assembly: 20 mm fiberboard + 50 mm XPS insulation + 20 mm embossed metal cladding | 0.40 | - | - | |

| Windows: Thermally broken aluminum windows | 2.70 | - | - | |

| Door: 80 mm standard aluminum panel | 2.70 | - | - | |

| Floor assembly: 20 mm ceramic tile + 50 mm cement fiberboard + 50 mm XPS insulation | 0.30 | - | - | |

| The collector wall of the toilet | 10 mm black aluminum absorber plate | - | 203 | 0.92 |

| 50 mm XPS insulation | - | 0.032 | 1.38 | |

| 200 mm high-density fiberboard | - | 0.330 | 2.51 |

| Treatment | A Exterior Wall Insulation Thickness (mm) | B Roof Insulation Thickness (mm) | C Window-to-Wall Ratio (%) | D Collector Wall Area (m2) | E Vent Spacing (Inlet/Outlet) (mm) | F Air Cavity Thickness (mm) | G Vent Area Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 3.45 | 1000 | 100 | 6 |

| 2 | 100 | 300 | 60 | 3.45 | 1000 | 20 | 2 |

| 3 | 300 | 300 | 60 | 2 | 1000 | 20 | 6 |

| 4 | 100 | 300 | 20 | 3.45 | 1800 | 20 | 6 |

| 5 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 2 | 1000 | 20 | 2 |

| 6 | 300 | 100 | 60 | 3.45 | 1800 | 20 | 2 |

| 7 | 300 | 300 | 20 | 3.45 | 1800 | 100 | 2 |

| 8 | 100 | 300 | 60 | 2 | 1800 | 100 | 6 |

| 9 | 300 | 100 | 60 | 3.45 | 1000 | 100 | 6 |

| 10 | 300 | 300 | 20 | 2 | 1000 | 100 | 2 |

| 11 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 2 | 1800 | 100 | 2 |

| 12 | 300 | 100 | 20 | 2 | 1800 | 20 | 6 |

| Treatment | E (mm) | F (mm) | G (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1800 | 40 | 6 |

| 2 | 1400 | 40 | 4 |

| 3 | 1400 | 40 | 4 |

| 4 | 1400 | 20 | 6 |

| 5 | 1800 | 60 | 4 |

| 6 | 1400 | 60 | 2 |

| 7 | 1400 | 40 | 4 |

| 8 | 1800 | 40 | 2 |

| 9 | 1400 | 60 | 6 |

| 10 | 1400 | 20 | 2 |

| 11 | 1000 | 60 | 4 |

| 12 | 1800 | 20 | 4 |

| 13 | 1400 | 40 | 4 |

| 14 | 1000 | 20 | 4 |

| 15 | 1000 | 40 | 6 |

| 16 | 1000 | 40 | 2 |

| 17 | 1400 | 40 | 4 |

| Source of Variance | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Significance Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.33 | 1.33 | 52.30 | 0.0019 | 3 |

| B | 0.0481 | 0.0481 | 1.89 | 0.2414 | 7 |

| C | 6.42 | 6.42 | 252.01 | <0.0001 | 2 |

| D | 19.35 | 19.35 | 759.26 | <0.0001 | 1 |

| E | 0.2523 | 0.2523 | 9.90 | 0.0346 | 6 |

| F | 0.4563 | 0.4563 | 17.90 | 0.0134 | 5 |

| G | 0.6912 | 0.6912 | 27.11 | 0.0065 | 4 |

| total regression | 28.56 | 4.08 | 160.05 | 0.0001 | significant |

| Treatment | E (mm) | F (mm) | G (%) | Average Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) | Maximum Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) | Minimum Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1800 | 40 | 6 | 7.87 | 20.36 | −1.40 |

| 2 | 1400 | 40 | 4 | 7.65 | 19.81 | −1.51 |

| 3 | 1400 | 40 | 4 | 7.61 | 19.76 | −1.58 |

| 4 | 1400 | 20 | 6 | 7.39 | 19.89 | −1.83 |

| 5 | 1800 | 60 | 4 | 7.54 | 19.31 | −1.47 |

| 6 | 1400 | 60 | 2 | 6.93 | 17.89 | −1.75 |

| 7 | 1400 | 40 | 4 | 7.65 | 19.81 | −1.51 |

| 8 | 1800 | 40 | 2 | 7.35 | 19.13 | −1.65 |

| 9 | 1400 | 60 | 6 | 7.58 | 19.46 | −1.44 |

| 10 | 1400 | 20 | 2 | 7.05 | 19.09 | −2.00 |

| 11 | 1000 | 60 | 4 | 7.28 | 18.69 | −1.59 |

| 12 | 1800 | 20 | 4 | 7.53 | 20.19 | −1.77 |

| 13 | 1400 | 40 | 4 | 7.60 | 19.81 | −1.51 |

| 14 | 1000 | 20 | 4 | 7.09 | 19.19 | −1.98 |

| 15 | 1000 | 40 | 6 | 7.57 | 19.70 | −1.52 |

| 16 | 1000 | 40 | 2 | 7.01 | 18.35 | −1.81 |

| 17 | 1400 | 40 | 4 | 7.62 | 19.74 | −1.62 |

| Source of Variance | Average Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) | Maximum Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) | Minimum Temperature of Toilet Room (°C) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | F-Value | p-Value | Sum of Squares | F-Value | p-Value | Sum of Squares | F-Value | p-Value | |

| E | 0.2245 | 275.88 | <0.0001 | 1.17 | 374.20 | <0.0001 | 0.0465 | 28.08 | 0.0011 |

| F | 0.0091 | 11.20 | 0.0123 | 1.13 | 362.07 | <0.0001 | 0.2211 | 133.49 | <0.0001 |

| G | 0.5356 | 658.35 | <0.0001 | 3.06 | 979.20 | <0.0001 | 0.1300 | 78.51 | <0.0001 |

| EF | 0.0081 | 9.96 | 0.0160 | 0.0361 | 11.54 | 0.0115 | 0.0020 | 1.22 | 0.3054 |

| EG | 0.0004 | 0.4917 | 0.5058 | 0.0036 | 1.15 | 0.3189 | 0.0004 | 0.2415 | 0.6382 |

| FG | 0.0240 | 29.53 | 0.0010 | 0.1482 | 47.39 | 0.0002 | 0.0049 | 2.96 | 0.1291 |

| E2 | 0.0030 | 3.70 | 0.0957 | 0.0202 | 6.46 | 0.0386 | 0.0000 | 0.0078 | 0.9322 |

| F2 | 0.2410 | 296.24 | <0.0001 | 0.5819 | 186.03 | <0.0001 | 0.1054 | 63.66 | <0.0001 |

| G2 | 0.0938 | 115.28 | <0.0001 | 0.4634 | 148.15 | <0.0001 | 0.0108 | 6.55 | 0.0376 |

| residual | 0.0057 | 0.0219 | 0.0116 | ||||||

| lack of fit (LOF) | 0.0036 | 2.25 | 0.2249 | 0.0174 | 5.13 | 0.0742 | 0.0011 | 0.1362 | 0.9334 |

| pure error | 0.0021 | 0.0045 | 0.0105 | ||||||

| aggregate | 1.17 | 6.73 | 0.5372 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Su, B.; Shen, Y.; Ding, J.; Shu, S.; Jia, Y. Optimization of a Passive Solar Heating System for Rural Household Toilets in Cold Regions Using TRNSYS. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411269

Fan S, Wang Z, Wang H, Su B, Shen Y, Ding J, Shu S, Jia Y. Optimization of a Passive Solar Heating System for Rural Household Toilets in Cold Regions Using TRNSYS. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411269

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Shengyuan, Zhenyuan Wang, Huihui Wang, Bowei Su, Yujun Shen, Jingtao Ding, Shangyi Shu, and Yiman Jia. 2025. "Optimization of a Passive Solar Heating System for Rural Household Toilets in Cold Regions Using TRNSYS" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411269

APA StyleFan, S., Wang, Z., Wang, H., Su, B., Shen, Y., Ding, J., Shu, S., & Jia, Y. (2025). Optimization of a Passive Solar Heating System for Rural Household Toilets in Cold Regions Using TRNSYS. Sustainability, 17(24), 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411269