Investigation of Coral Reefs for Coastal Protection: Hydrodynamic Insights and Sustainable Flow Energy Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling Coral Structure: Depth Ratio and Porosity

| Acropora Species | Sea Depth (m) | Coral Height (m) | Sea Depth Reference | Coral Height Reference | Ratio (Coral Height/Water Depth) (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acropora pharaonis Site 7 | 4 | 2 | [17] | [18] | 0.5 |

| Acropora pharaonis Site 27 | 7 | 2 | [17] | [19] | 0.29 |

| Acropora pharaonis Site 26 | 5 | 2 | [17] | [19] | 0.4 |

| Acropora cervicornis | 0–5 | 2 | [20] | [21] | 0.4–0.8 |

| Acropora muricata | 5 | 1 | [22] | [23] | 0.2 |

| Acropora prolifera | 7 | 0.02 | [24] | [25] | 0.00286 |

2.2. 3D-Printed Coral Reefs

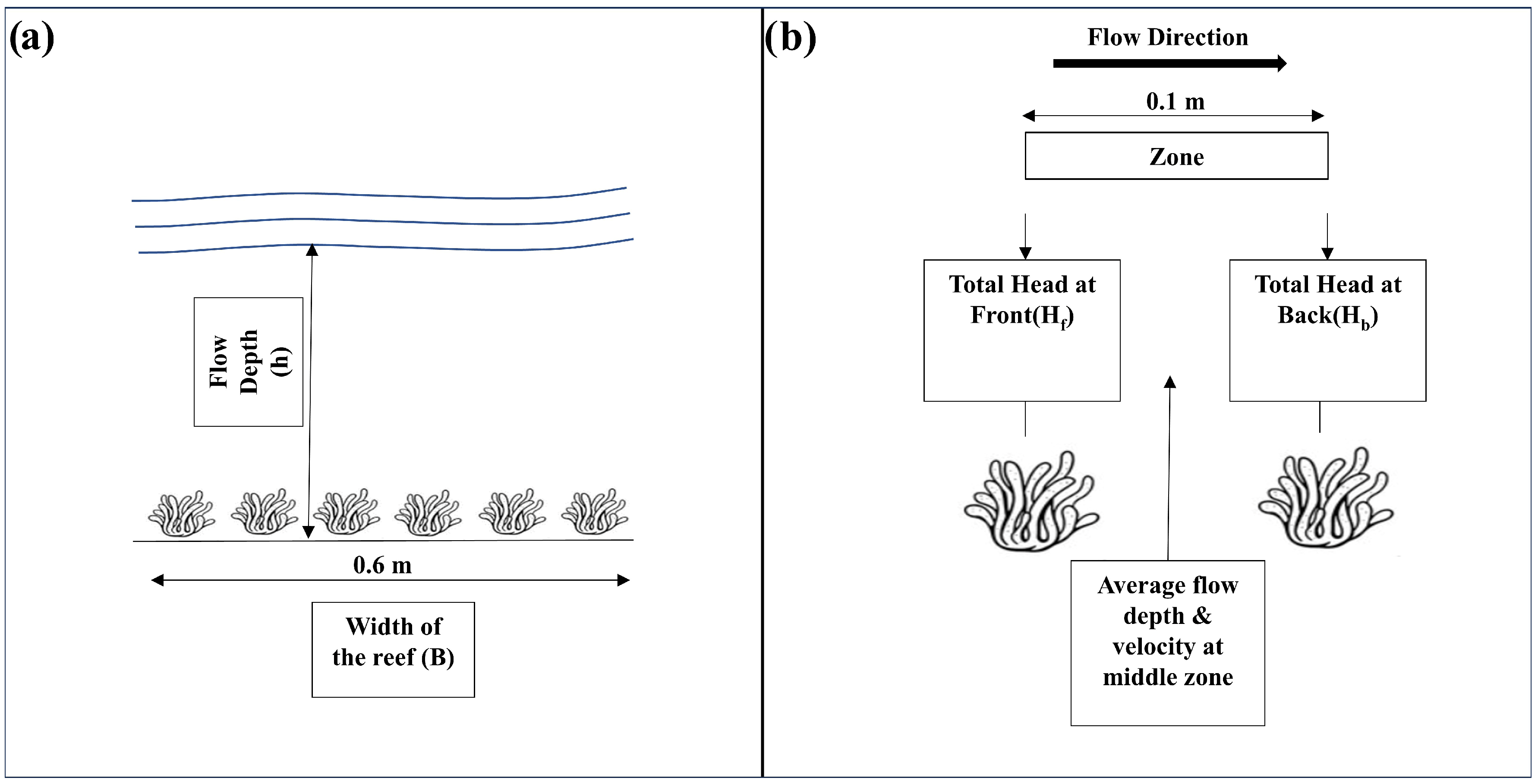

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. Nondimensional Numbers of the Flow–Coral Interaction and Test Cases

2.5. Roughness Estimation

3. Results

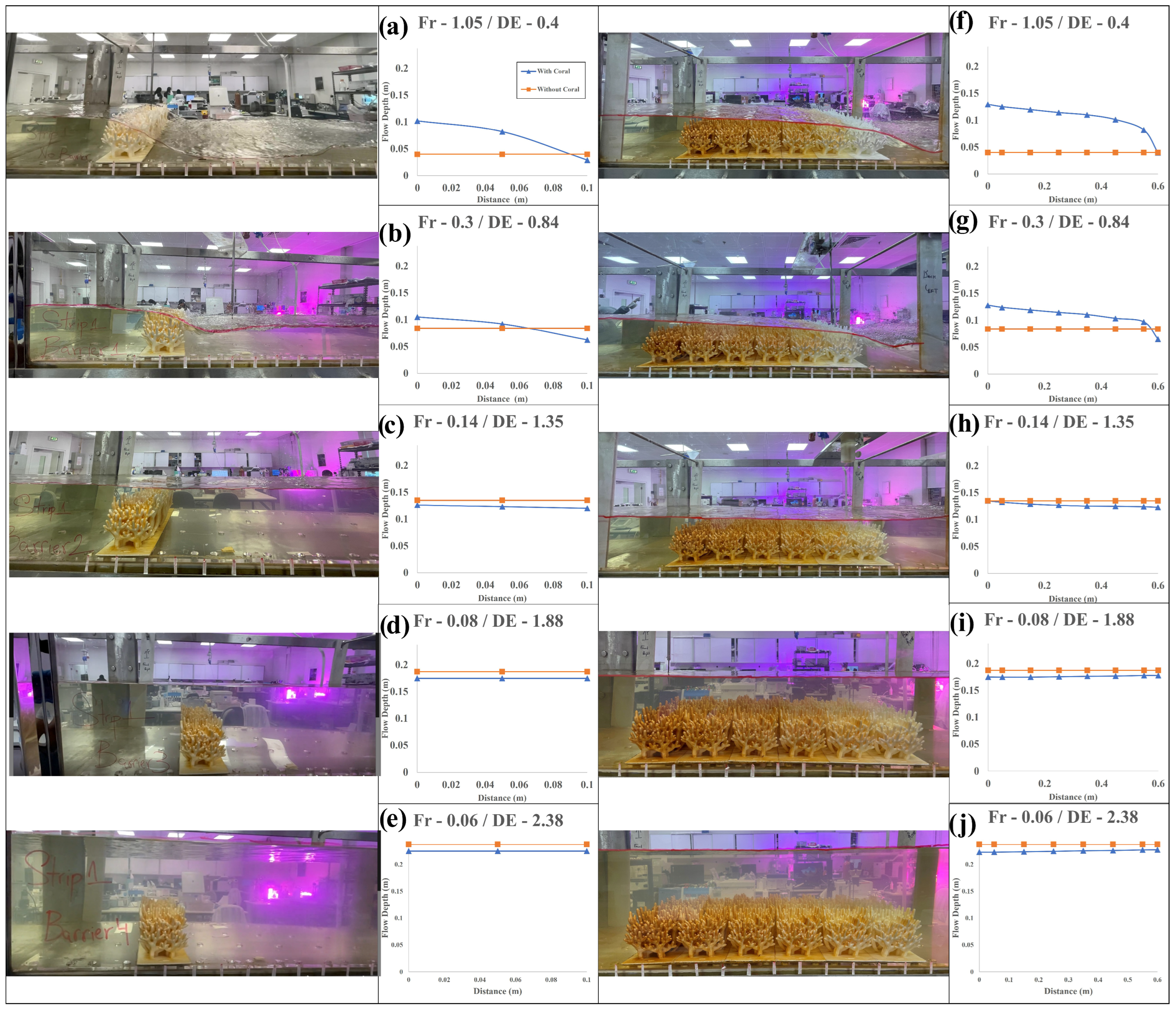

3.1. Spatial Variation in Flow Depth over the Reef

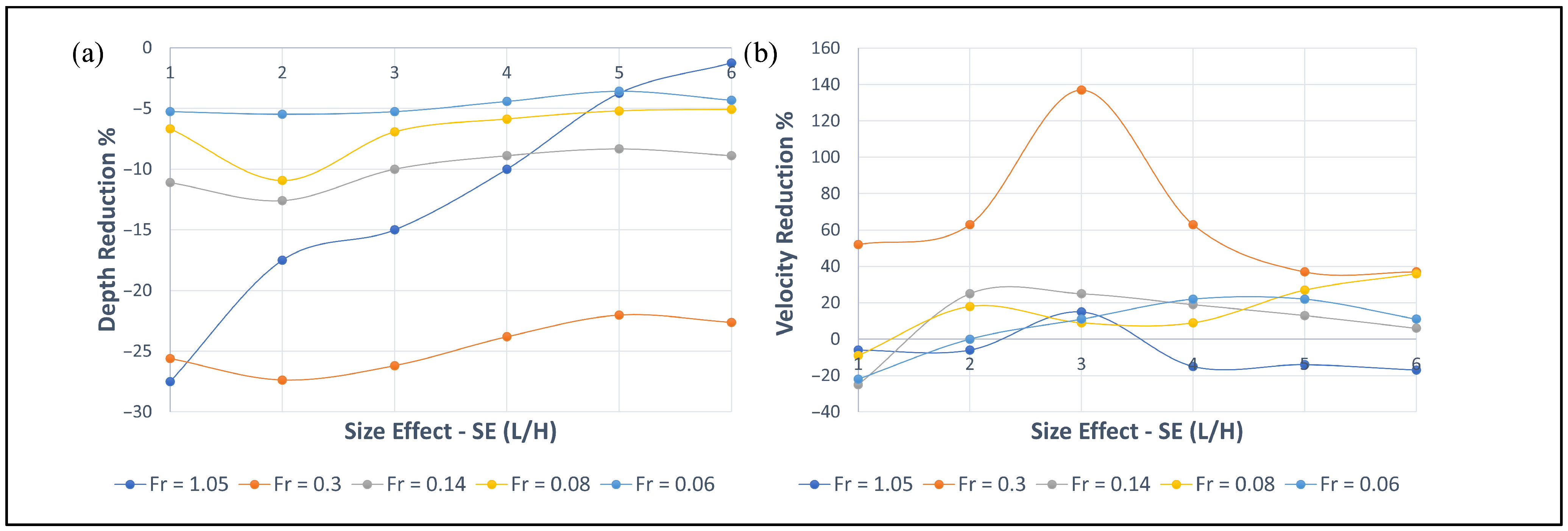

3.2. Flow Depth and Velocity Reduction Behind the Reef

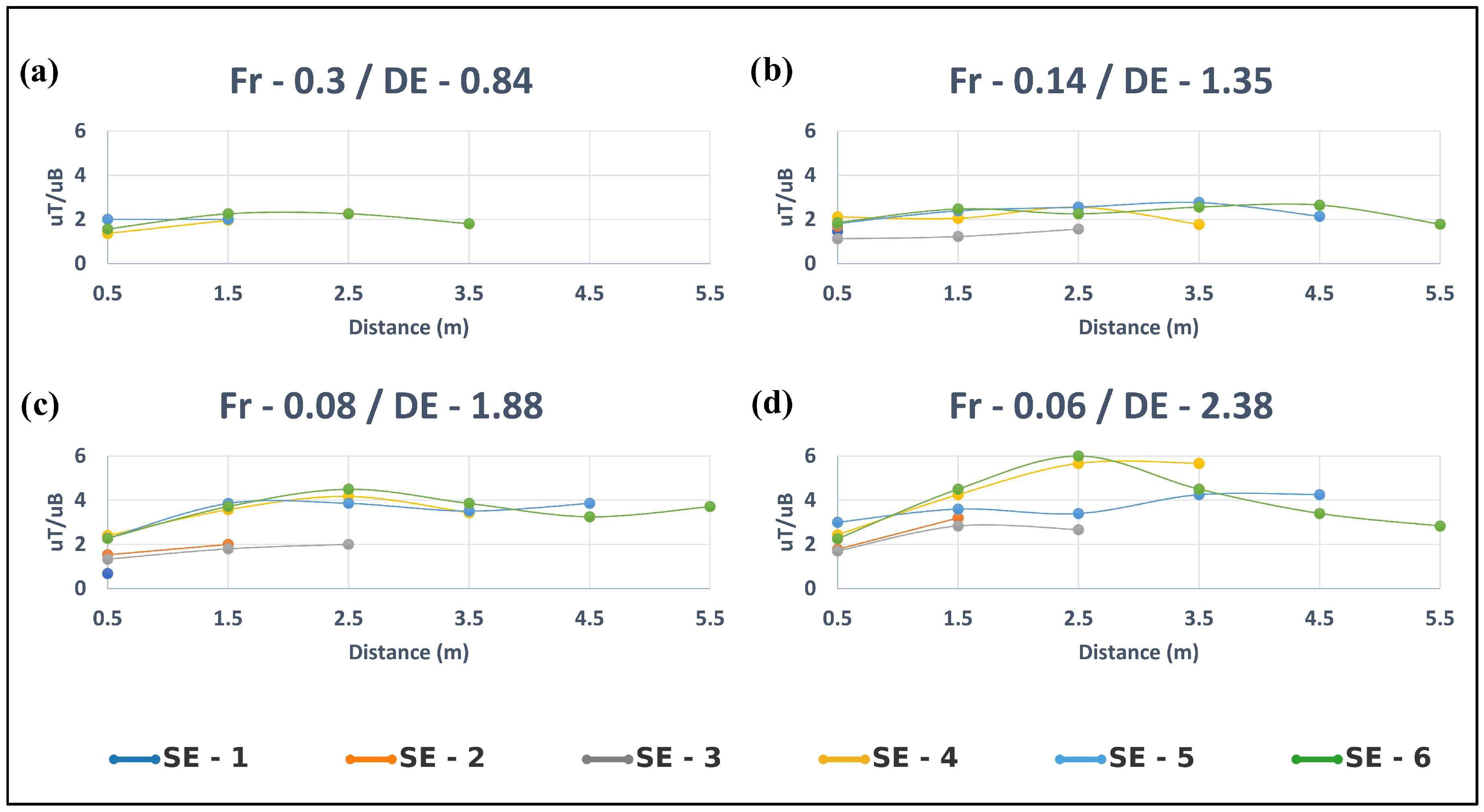

3.3. Two-Layered Flow Analysis

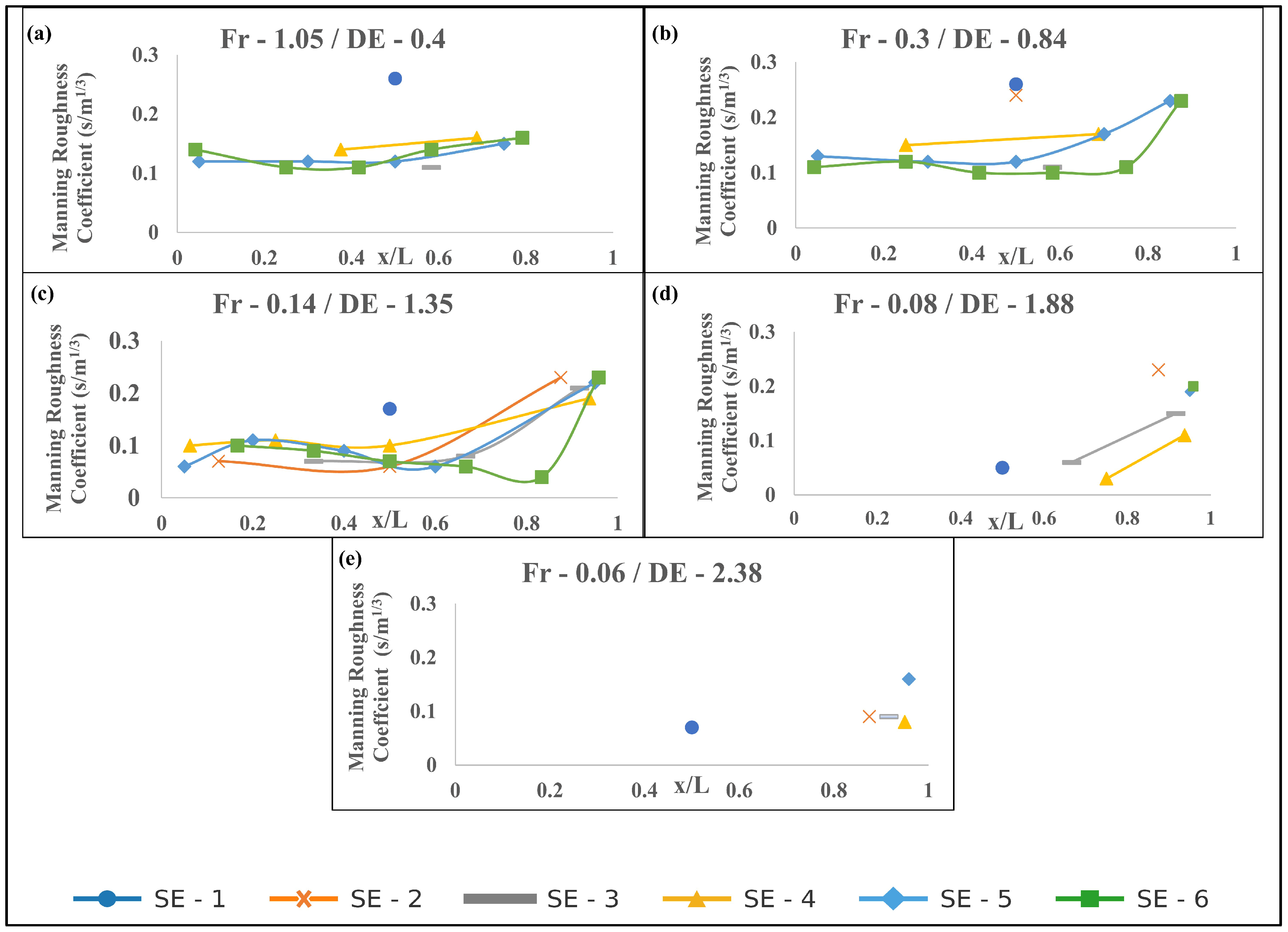

3.4. Coral Roughness Coefficient

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution to Sustainable Coastal Engineering

4.2. Flow Behavior and Depth Variation

4.3. Contextualizing with Previous Research

4.4. Spatial Variation and Velocity Layers

4.5. Influence of Coral Structure and Flow Parameters

4.6. Implications for Modeling and Reef Management

5. Conclusions

- Analysis of the spatial flow depth variation for narrow and wide corals showed that in shallower and fast flows (high Fr and low DE), the depth initially increased at the reef front (due to reflection) but gradually decreased toward the leeward end. For deeper slow flows (low Fr and high DE), the reduction observed in the coral case compared to the case without corals was less significant but remained constant throughout the reef for narrower and wider corals. It was also observed that the water surface gradient was higher for wider corals compared to narrower corals for fast and shallow flows at the reef end.

- Shallower fast flow (greater Fr) led to higher flow depth reduction, with consistent reduction magnitudes except for Fr–1.05, where depth reduction decreased over wider corals (higher SE). Velocity reductions for narrow and wide corals were more notable for shallow and fast flows (Fr–1.05). In other flow cases of Fr = 0.3, 0.14, 0.08, and 0.06, velocity increments occurred over wider corals (increasing SE), which is due to the two-layered velocity effect.

- The two-layered flow analysis revealed that the flow velocity above the coral was considerably greater than the flow through the coral. The difference in velocity over and through the corals for deep and slow flows (lower Fr and higher DE) was six times.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elliff, C.I.; Silva, I.R. Coral reefs as the first line of defense: Shoreline protection in face of climate change. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 127, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M.; Reguero, B.G.; Mendoza, E.; Secaira, F.; Silva, R. Coral reef geometry and hydrodynamics in beach erosion control in North Quintana Roo, Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 684732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monismith, S.G. Hydrodynamics of coral reefs. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2007, 39, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocking, J.B.; Laforsch, C.; Sigl, R.; Reidenbach, M.A. The role of turbulent hydrodynamics and surface morphology on heat and mass transfer in corals. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrario, F.; Beck, M.W.; Storlazzi, C.D.; Micheli, F.; Shepard, C.C.; Airoldi, L. The effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, R.J.; Falter, J.L.; Monismith, S.G.; Atkinson, M.J. A numerical study of circulation in a coastal reef-lagoon system. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 2009, 114, C06022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelvink, F.E.; Storlazzi, C.D.; Van Dongeren, A.R.; Pearson, S.G. Coral reef restorations can be optimized to reduce coastal flooding hazards. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 653945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falter, J.L.; Lowe, R.J.; Zhang, Z.; McCulloch, M. Physical and biological controls on the carbonate chemistry of coral reef waters: Effects of metabolism, wave forcing, sea level, and geomorphology. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Cano, J.D.; Osorio, A.; Peláez-Zapata, D. Ecosystem management tools to study natural habitats as wave damping structures and coastal protection mechanisms. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 130, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Berman, O.; Neri, R.; Tarazi, E.; Parnas, H.; Lotan, O.; Zoabi, M.; Josef, N.; Shashar, N. Three-Dimensional-Printed Coral-like Structures as a Habitat for Reef Fish. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidenbach, M.A.; Koseff, J.R.; Monismith, S.G. Laboratory experiments of fine-scale mixing and mass transport within a coral canopy. Phys. Fluids 2007, 19, 075107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, V.; Pawlak, G. Observations of Bed Roughness of a Coral Reef. J. Coast. Res. 2008, 24, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, H.J.S.; Samarawickrama, S.P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Hettiarachchi, S.S.L.; Voropayev, S. Effects of porous barriers such as coral reefs on coastal wave propagation. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2008, 1, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendrik, F.; Houseago, R.C.; Hackney, C.R.; Parsons, D.R. Microplastic trapping efficiency and hydrodynamics in model coral reefs: A physical experimental investigation. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pagán, B.S.; Mercado-Molina, A.E. Evaluation of the effectiveness of 3D-printed corals to attract coral reef fish at Tamarindo Reef, Culebra, Puerto Rico. Conserv. Evid. 2018, 15, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Manzello, D.P. Bioerosion and Coral Reef Growth: A Dynamic Balance. In Coral Reefs in the Anthropocene; Birkeland, C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Claereboudt, M.R. Reef Corals and Coral Reefs of the Gulf of Oman; Historical Association of Oman: Muscat, Oman, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C.C. Staghorn Corals of the World: A Revision of the Coral Genus Acropora (Scleractinia; Astrocoeniina; Acroporidae); CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, UK, 1999.

- Shafir, S.; Rinkevich, B. Integrated long-term mid-water coral nurseries: A management instrument evolving into a floating ecosystem. Univ. Maurit. Res. J. 2010, 16, 365–386. [Google Scholar]

- Alcolado, P.; Claro-Madruga, R.; Menéndez-Macías, G.; García-Parrado, P.; Martínez-Daranas, B.; Sosa, M. The Cuban coral reefs. In Latin American Coral Reefs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnicliffe, V. Breakage and propagation of the stony coral Acropora cervicornis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 2427–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulyani, S.; Tuwo, A.; Syamsuddin, R.; Jompa, J. Effect of seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii aquaculture on growth and survival of coral Acropora muricata. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2018, 11, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, G. Annotated check list of corals in the Mascarene Archipelago, Indian Ocean. Atoll Res. Bull. 1977, 203, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precht, W.F.; Vollmer, S.V.; Modys, A.B.; Kaufman, L. Fossil Acropora prolifera (Lamarck, 1816) reveals coral hybridization is not only a recent phenomenon. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 2019, 132, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, P.L. Marine Invertebrates and Plants of the Living Reef; TFH Publications: Neptune, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter, E. Skeletal development in Acropora cervicornis: I. Patterns of calcium carbonate accretion in the axial corallite. Coral Reefs 1982, 1, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, K.; Van Woesik, R. Spatial differences and seasonal changes of net carbonate accumulation on some coral reefs of the Ryukyu Islands, Japan. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2000, 252, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongo, C.; Kayanne, H. Holocene coral reef development under windward and leeward locations at Ishigaki Island, Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Sediment. Geol. 2009, 214, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore, N.E. Diagenesis and porosity modification in Acropora palmata, Pleistocene of Barbados, West Indies. J. Sediment. Res. 1970, 40, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msallem, B.; Sharma, N.; Cao, S.; Halbeisen, F.S.; Zeilhofer, H.-F.; Thieringer, F.M. Evaluation of the dimensional accuracy of 3D-printed anatomical mandibular models using FFF, SLA, SLS, MJ, and BJ printing technology. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruth, J.-P.; Froyen, L.; Rombouts, M.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; Mercelis, P. New ferro powder for selective laser sintering of dense parts. CIRP Ann. 2003, 52, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Nandasena, N.A.K. Experimental and numerical assessment of marine flood reduction by coral reefs. Nat. Hazards Res. 2023, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, M.R.; Colleter, G. Wave-generated flow on coral reefs—An analysis for two-dimensional horizontal reef-tops with steep faces. Coast. Eng. 2005, 52, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.; Koseff, J.; Monismith, S. Effects of the depth to coral height ratio on drag coefficients for unidirectional flow over coral. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, H. 3D mesoscopic investigation of the specimen aspect-ratio effect on the compressive behavior of coral aggregate concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 198, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foubert, A.; Huvenne, V.; Wheeler, A.; Kozachenko, M.; Opderbecke, J.; Henriet, J.-P. The Moira Mounds, small cold-water coral mounds in the Porcupine Seabight, NE Atlantic: Part B—Evaluating the impact of sediment dynamics through high-resolution ROV-borne bathymetric mapping. Mar. Geol. 2011, 282, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L. Flow resistance in broad shallow grassed channels. J. Hydraul. Div. 1976, 102, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltz, M.A.; Arslan, A.B.; Lane, L.J. Hydraulic roughness coefficients for native rangelands. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 1992, 118, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, N.A.K.; Chawdhary, I. Coral mitigates high-energy marine floods: Numerical analysis on flow–coral interaction. Sci. J. King Faisal Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R.C.; Williams, S.L. Effects of algal turf canopy height and microscale substratum topography on profiles of flow speed in a coral forereef environment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1993, 38, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, C.J. Wave-breaking hydrodynamics within coral reef systems and the effect of changing relative sea level. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 30007–30019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.; Bilger, R. Effects of water velocity on phosphate uptake in coral reef-flat communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1992, 37, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-C.; Lenain, L.; Melville, W.K.; Middleton, J.H.; Reineman, B.; Statom, N.; McCabe, R.M. Dissipation of wave energy and turbulence in a shallow coral reef lagoon. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, C03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.S.; Monismith, S.G.; Koweek, D.A.; Torres, W.I.; Dunbar, R.B. Thermodynamics and hydrodynamics in an atoll reef system and their influence on coral cover. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2016, 61, 2191–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monismith, S.G.; Rogers, J.S.; Koweek, D.; Dunbar, R.B. Frictional wave dissipation on a remarkably rough reef. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.J.; Falter, J.L.; Bandet, M.D.; Pawlak, G.; Atkinson, M.J.; Monismith, S.G.; Koseff, J.R. Spectral wave dissipation over a barrier reef. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, C04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, A.W.M.; Ghisalberti, M.; Peterson, M.; Farooji, V.E. A framework to quantify flow through coral reefs of varying coral cover and morphology. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Whittaker, C.; Melville, B. The effects of structural complexity on the turbulent structure around cubic artificial reefs with multiscale cavities. Ocean Eng. 2025, 334, 121594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Natan, A.; Chernihovsky, N.; Shashar, N. Augmenting Coral Growth on Breakwaters: A Shelter-Based Approach. Coasts 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Qin, P.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C. Prediction of seawater intrusion run-up distance based on K-means clustering and ANN model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Baptist, M.J.; Alkharoubi, A.I.K.; Nasca, S.; Cavallaro, L.; Foti, E.; Musumeci, R.E. Nature-based solutions as building blocks for coastal flood risk reduction: A model-based ecosystem service assessment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coral Reef Length (m) | Froude Number (Fr) | Depth Effect (DE) | Size Effect (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No strip (Control) | - | 1.05 | - | - |

| - | 0.3 | - | - | |

| - | 0.14 | - | - | |

| - | 0.08 | - | - | |

| - | 0.06 | - | - | |

| Strip 1 | 0.1 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 1 |

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 1 | |

| Strip 2 | 0.2 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 2 |

| 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 2 | |

| 0.2 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 2 | |

| 0.2 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 2 | |

| 0.2 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 2 | |

| Strip 3 | 0.3 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 3 |

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 3 | |

| 0.3 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 3 | |

| 0.3 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 3 | |

| 0.3 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 3 | |

| Strip 4 | 0.4 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 4 |

| 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 4 | |

| 0.4 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 4 | |

| 0.4 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 4 | |

| 0.4 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 4 | |

| Strip 5 | 0.5 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 5 |

| 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 5 | |

| 0.5 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 5 | |

| 0.5 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 5 | |

| 0.5 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 5 | |

| Strip 6 | 0.6 | 1.05 | 0.4 | 6 |

| 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.84 | 6 | |

| 0.6 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 6 | |

| 0.6 | 0.08 | 1.88 | 6 | |

| 0.6 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karim, F.; Nandasena, N.A.K.; Terry, J.P.; Mohamed, M.M.; Xu, Z. Investigation of Coral Reefs for Coastal Protection: Hydrodynamic Insights and Sustainable Flow Energy Reduction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410996

Karim F, Nandasena NAK, Terry JP, Mohamed MM, Xu Z. Investigation of Coral Reefs for Coastal Protection: Hydrodynamic Insights and Sustainable Flow Energy Reduction. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410996

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarim, Faisal, Napayalage A. K. Nandasena, James P. Terry, Mohamed M. Mohamed, and Zhonghou Xu. 2025. "Investigation of Coral Reefs for Coastal Protection: Hydrodynamic Insights and Sustainable Flow Energy Reduction" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410996

APA StyleKarim, F., Nandasena, N. A. K., Terry, J. P., Mohamed, M. M., & Xu, Z. (2025). Investigation of Coral Reefs for Coastal Protection: Hydrodynamic Insights and Sustainable Flow Energy Reduction. Sustainability, 17(24), 10996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410996