The Effect of Eco-Recreational and Environmental Attitudes on Environmental Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

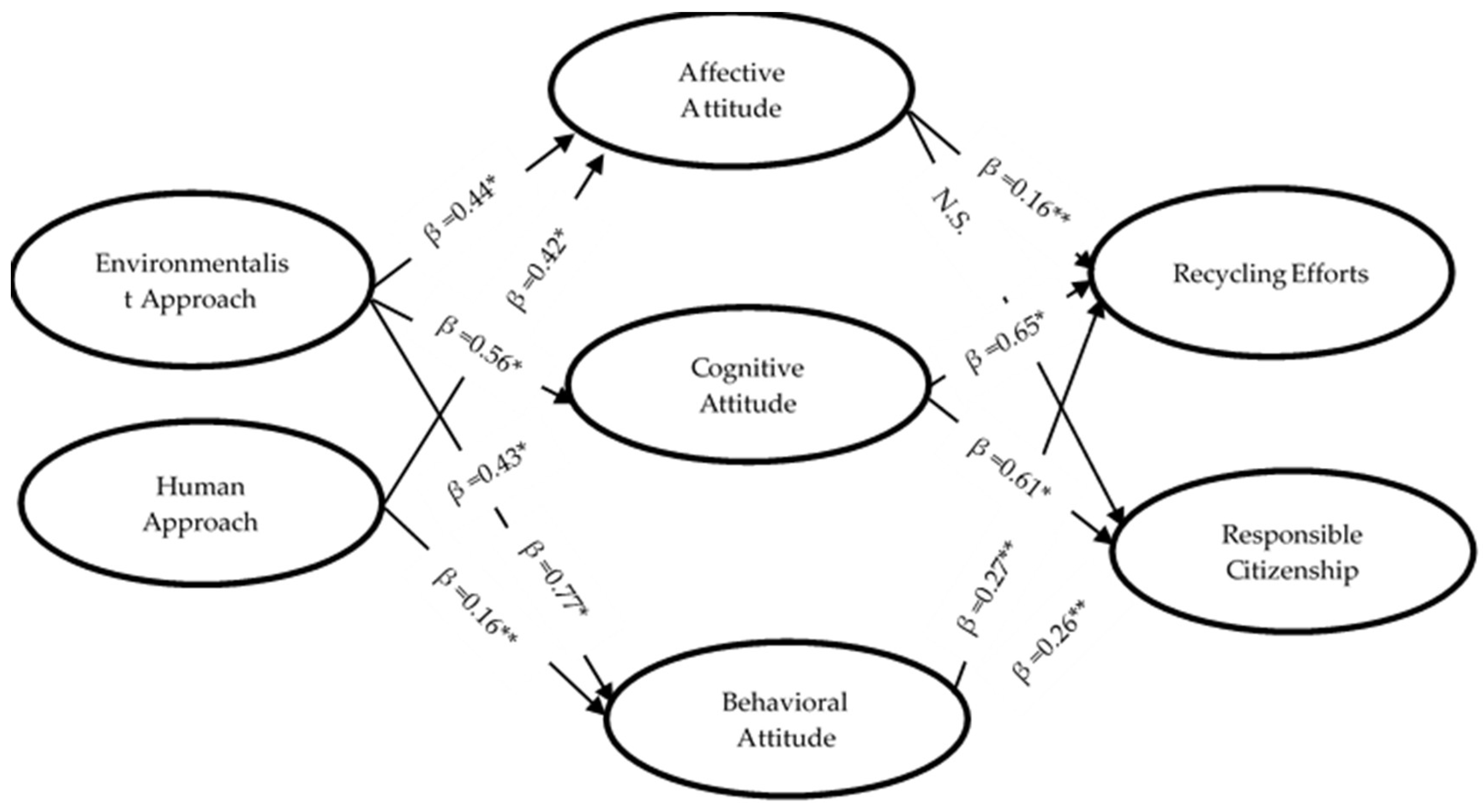

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection Tool and Data Collection Process

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Energy Review 2025: CO2 Emissions. 2025. Available online: https://iea.org (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Forest Declaration Assessment Partners. 2024 Forest Declaration Assessment: Forests Under Fire. 2024. Available online: https://forestdeclaration.org (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Living Planet Report 2024: A Planet in Crisis. 2024. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ritchie, H. Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfa, V.; Septiana, A. Impact of Climate Change on Environmental Health: Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Quality of Life. Environ. Educ. Conserv. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koessler, A.-K.; Vorlaufer, T.; Fiebelkorn, F. Social Norms and Climate-Friendly Behavior of Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Gupta, J.J.; Hussain, S. Impact of Travel Motivation on Tourist’s Attitude Toward Destination: Evidence of Mediating Effect of Destination Image. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 946–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviour: Effects of Socioeconomic, Subjective, and Psychological Well-Being Factors from 37 Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J. The Environmental Attitudes Inventory: A Valid and Reliable Measure to Assess the Structure of Environmental Attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and Social Factors That Influence Pro-Environmental Concern and Behaviour: A Review: Personal And Social Factors That Influence Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, I.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Navarro, O. Environmental Attitudes in Context: Conceptualisations, Measurements and Related Factors of Environmental Attitudes. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1219471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, L.; Fazio, A.; Pelloni, A. Pro-Environmental Attitudes, Local Environmental Conditions and Recycling Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. Recreational Landscape Perception and Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Place Identity and pro-Environmental Behavioral Spillover. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1616154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayolla, R.; Escadas, M.; McCullough, B.P.; Biscaia, R.; Cabilhas, A.; Santos, T. Does Pro-Environmental Attitude Predicts pro-Environmental Behavior? Comparing Sustainability Connection in Emotional and Cognitive Environments among Football Fans and University Students. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos-Espinoza, I.I.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Gil-López, A.J.; Díaz-Reza, J.R. Effect of Environmental Knowledge on Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: A Comparative Analysis between Engineering Students and Professionals in Ciudad Juárez (Mexico). J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2025, 15, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Castro, S.L.; Souza, A.S. Psychological Barriers Moderate the Attitude-Behavior Gap for Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Kanitsar, G.; Seifert, M. Behavioral Barriers Impede Pro-Environmental Decision-Making: Experimental Evidence from Incentivized Laboratory and Vignette Studies. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 225, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.L.; Chiarella, S.G.; Raffone, A.; Simione, L. Understanding the Environmental Attitude-Behaviour Gap: The Moderating Role of Dispositional Mindfulness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, Norms, and Intrinsic Motivation to Act Proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.S.; Elkoca, A.; Gökçay, G.; Yilmaz, D.A.; Yıldız, M. The Relationship between Environmental Literacy, Ecological Footprint Awareness, and Environmental Behavior in Adults. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Forster, P. The Relationship between Connectedness to Nature, Environmental Values, and pro-Environmental Behaviours. Reinvention Int. J. Undergrad. Res. 2015, 8. Available online: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/research/reinvention/archive/volume8issue2/pereira/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. The Effects of Recreation Experience, Environmental Attitude, and Biospheric Value on the Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Nature-Based Tourists. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.C.-H.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to Nature: Children’s Affective Attitude Toward Nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.-S. Relationships between Outdoor Recreation-Associated Flow, pro-Environmental Attitude, and pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecke, S.L.; Huber, J.; Kirchler, M.; Schwaiger, R. Nature Experiences and Pro-Environmental Behavior: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the Natural Environment: The Role of Affective Connection and Identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzini, A.; Valdrighi, G.; Fiorenza, M.; Duradoni, M. The Relationship Between Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kement, Ü.; Karaküçük, S.; Çavuşoğlu, S. Ekorekreatif Tutum Ölçeği Geliştirilmesi: Geçerlik ve Güvenilirlik Çalışması. Tour. Recreat. 2021, 3, 34–54. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.J.; Krettenauer, T. Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behaviour from Early Adolescence to Adulthood: A Comparison of Urban and Rural Canada. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Promoting Environmentally Sustainable Attitudes and Behaviour through Free-choice Learning Experiences: What Is the State of the Game? Environ. Educ. Res. 2005, 11, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Osmani, M. Building Information Modelling (BIM) Driven Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism. Buildings 2023, 13, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Zhao, M.; Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Xie, C.; Ding, Y. Does Environmental Interpretation Impact Public Ecological Flow Experience and Responsible Behavior? A Case Study of Potatso National Park, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Teng, L.; Ji, J. Impact of Environmental Regulations on Eco-Innovation: The Moderating Role of Top Managers’ Environmental Awareness and Commitment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 2229–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Trujillo, E.; Pérez-Gálvez, J.C.; Orts-Cardador, J.J. Exploring Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior: A Bibliometric Analysis over Two Decades (1999–2023). J. Tour. Futur. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Peng, P.; Fan, S.; Liang, J.; Ye, J.; Ma, Y. Formation Mechanism of Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior in Wuyishan National Park, China, Based on Ecological Values. Forests 2024, 15, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of Human Connection to Nature and Proenvironmental Behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z. Structural Relationship between Ecotourism Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior Intention in Nature-Based Camping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Si, W. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Examining the Role of Ecological Value Cognition, Environmental Attitude, and Place Attachment among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Wuyun, T. Environmental Value and Pro-Environmental Behavior among Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Moral Anger. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 771421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Soylu, Y.; Atay, L.; Timothy, D.J. Environmentally Friendly Behaviors of Recreationists and Natural Area Tourists: A Comparative Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, A. A Note on Environmental Concern in a Developing Country: Results From an Istanbul Survey. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytaç, M.; Öngen, B. Doğrulayıcı Faktör Analizi Ile Yeni Çevresel Paradigma Ölçeğinin Yapı Geçerliliğinin Incelenmesi. İstatistikçiler Derg. İstatistik Ve Aktüerya 2012, 5, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D.; Yavetz, B.; Pe’er, S. Environmental Literacy in Teacher Training in Israel: Environmental Behavior of New Students. J. Environ. Educ. 2006, 38, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, S.; Yılmaz, M. Çevre Davranış Ölçeğinin Türkçe’ye Uyarlanması. Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2013, 33, 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G. Reliability and Validity Assessment. In Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, K.; Huang, D. Natural World Heritage Conservation and Tourism: A Review. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, S.; Simpson, S. Anthropocentric and Ecocentric: An Application of Environmental Philosophy to Outdoor Recreation and Environmental Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 38, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Ranney, M.; Hartig, T.; Bowler, P.A. Ecological Behavior, Environmental Attitude, and Feelings of Responsibility for the Environment. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-Environmental Behavior from a Socialcognitive Theory Perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçakese, A.; Demirel, M.; Yolcu, A.F.; Gümüş, H.; Ayhan, C.; Sarol, H.; Işık, Ö.; Harmandar Demirel, D.; Stoica, L. Nature Relatedness, Flow Experience, and Environmental Behaviors in Nature-Based Leisure Activities. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1397148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyem, J. Outdoor Recreation and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B. The Mediation Effect of Outdoor Recreation Participation on Environmental Attitude-Behavior Correspondence. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, G.L.; Richardson, S.J.; Harré, N.; Hodges, D.; Lyver, P.O.; Maseyk, F.J.; Taylor, R.; Todd, J.H.; Tylianakis, J.M.; Yletyinen, J. Evaluating the Role of Social Norms in Fostering Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 620125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipeolu, A.A.; Ibem, E.O.; Oriola, O.A. Influence of Green Infrastructure on Residents’ Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2022, 6, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kement, U.; Dogan, S.; Baydeniz, E.; Bayar, S.B.; Erkol Bayram, G.; Basar, B. Effect of Environmental Attitude on Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Comparative Analysis among Green and Non-Green Hotel Guests in Turkiye. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1640–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Y.; Anasori, E. Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Residents: Impact of Mindfulness, Enjoyment of Nature and Sustainable Attitude. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Berenguer, J. Environmental Values, Beliefs, and Actions: A Situational Approach. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.G. Values and Their Effect on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, D.; Nosrati, S.; Kim, S. Do Cultural and Individual Values Influence Sustainable Tourism and Pro-Environmental Behavior? Focusing on Chinese Millennials. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | f | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 207 | 49.1 |

| Female | 215 | 50.9 |

| Age | ||

| 21–30 | 99 | 23.5 |

| 31–40 | 86 | 20.4 |

| 41–50 | 87 | 20.6 |

| 51–60 | 78 | 18.5 |

| 61 or more | 72 | 17.1 |

| Marial Status | ||

| Married | 168 | 39.8 |

| Single | 254 | 60.2 |

| Status | ||

| Research Assistant | 80 | 19.0 |

| Lecturer | 77 | 18.2 |

| Assist. Prof. Dr. | 93 | 22.0 |

| Assoc. Prof. Dr. | 89 | 21.1 |

| Prof. Dr. | 83 | 19.7 |

| Factors/Expressions | Standard Deviation | t-Value | CR | AVE | CA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Environmental Paradigm | ||||||

| Environmentalist Approach | 0.889 | 0.627 | 0.874 | |||

| The population is growing at a rate that exceeds the carrying capacity of the world. | 0.787 | 0.61 | ||||

| People are overusing and consuming nature and natural resources. | 0.680 | 14.66 * | 0.46 | |||

| Animals and plants have at least as much right to life as humans. | 0.675 | 14.54 * | 0.45 | |||

| Although humans possess unique abilities such as intelligence, they are still subject to the laws of nature. | 0.589 | 12.32 * | 0.34 | |||

| Nature has a delicate balance that can be easily disrupted. | 0.838 | 19.00 * | 0.70 | |||

| If current consumption habits are not changed, we will face major environmental problems in the future. | 0.806 | 18.10 * | 0.65 | |||

| Human Approach | 0.841 | 0.639 | 0.837 | |||

| People have the right to change nature according to their own desires and wishes. | 0.768 | 0.59 | ||||

| Thanks to their intellect and creativity, humans will make the world livable in all circumstances. | 0.810 | 20.76 * | 0.65 | |||

| In fact, if we know how to use and develop it correctly, the world’s natural resources are unlimited. | 0.821 | 21.14 * | 0.67 | |||

| Eco-Recreational Attitude | ||||||

| Emotional Attitude | 0.878 | 0.592 | 0.884 | |||

| I enjoy participating in eco-recreational activities. | 0.801 | 14.85 * | 0.64 | |||

| Participating in eco-recreational activities gives me pleasure. | 0.805 | 14.92 * | 0.65 | |||

| Participating in eco- recreational activities brings me peace. | 0.873 | 15.95 * | 0.76 | |||

| Participating in eco- recreational activities is fun. | 0.664 | 18.12 * | 0.44 | |||

| Failure to comply with the carrying capacity (physical) of eco- recreational activity areas worries me about the loss of natural areas for future generations. | 0.686 | 0.47 | ||||

| Cognitive Attitude | 0.917 | 0.614 | 0.926 | |||

| Responsible local governments must regularly collect waste from eco-recreational activity areas. | 0.758 | 17.41 * | 0.57 | |||

| Signage must be present in areas where eco-recreational activities take place. | 0.772 | 18.17 * | 0.59 | |||

| Plants and animals must be protected while eco-recreational activities are being carried out. | 0.785 | 18.74 * | 0.61 | |||

| Even if eco-recreational activities restrict mobility, natural areas with sensitive structures must be protected. | 0.786 | 18.78 * | 0.62 | |||

| Eco-recreational activities contribute to economic growth. | 0.800 | 18.70 * | 0.64 | |||

| People do not have the right to harm the environment to gain economic benefits from eco-recreational activities. | 0.777 | 18.02 * | 0.60 | |||

| Eco-recreationists should be educated on the conscious use of natural resources. | 0.809 | 0.65 | ||||

| Behavioral Attitude | 0.927 | 0.561 | 0.928 | |||

| I avoid using motor vehicles when going to eco-recreational activity areas. | 0.684 | 14.08 * | 0.46 | |||

| I try to dispose of the waste I generate during my eco-recreational activities in recycling bins. | 0.796 | 16.62 * | 0.63 | |||

| I pick up litter I find on the ground during my eco-recreational activities. | 0.724 | 14.97 * | 0.52 | |||

| In my eco-recreational activities, I prefer to stay within the permitted area when using protected areas. | 0.805 | 16.84 * | 0.65 | |||

| In my eco-recreational activities, I consume organic food and beverages. | 0.688 | 14.19 * | 0.47 | |||

| I use recyclable materials (tools, clothing, etc.) in my eco-recreational activities. | 0.710 | 14.65 * | 0.50 | |||

| In my eco-recreational activities, I take care not to harm plants and animals. | 0.820 | 17.18 * | 0.67 | |||

| When participating in eco-recreational activities, I prefer to stay at environmentally conscious facilities (such as green hotels). | 0.816 | 17.08 * | 0.66 | |||

| I would like to purchase the food and beverages I consume during my eco-recreational activities from local producers operating in the area. | 0.688 | 14.18 * | 0.47 | |||

| I follow social media groups (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.) focused on environmental protection and eco-recreational activities. | 0.740 | 0.54 | ||||

| Environmental Behavior | ||||||

| Recycling Efforts | 0.854 | 0.665 | 0.845 | |||

| I take waste such as newspapers and plastic bottles to recycling collection points. | 0.848 | 0.72 | ||||

| I return beverage bottles with a deposit. | 0.907 | 23.57 * | 0.82 | |||

| I put used batteries in appropriate collection boxes for batteries instead of trash cans. | 0.675 | 16.43 * | 0.45 | |||

| Responsible Citizenship | 0.825 | 0.613 | 0.821 | |||

| I send letters to the media about environmental issues. | 0.826 | 0.68 | ||||

| I participate in campaigns for the protection and cleaning of public places. | 0.777 | 21.01 * | 0.60 | |||

| I warn people who litter in public areas or harm the environment. | 0.744 | 18.95 * | 0.55 |

| Relationships | β | p | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Environmentalist approach → Affective attitude | 0.44 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H1b: Environmentalist approach → Cognitive attitude | 0.56 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H1c: Environmentalist approach → Behavioral attitude | 0.77 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2a: Human approach → Affective attitude | 0.42 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2b: Human approach → Cognitive attitude | 0.43 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2c: Human approach → Behavioral attitude | 0.16 | 0.032 | Accepted |

| H3a: Affective attitude → Recycling efforts | 0.16 | 0.029 | Accepted |

| H3b: Affective attitude → Responsible citizenship | 0.03 | 0.540 | Rejected |

| H4a: Cognitive attitude → Recycling efforts | 0.65 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H4b: Cognitive attitude → Responsible citizenship | 0.61 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H5a: Behavioral attitude → Recycling efforts | 0.27 | 0.048 | Accepted |

| H5b: Behavioral attitude → Responsible citizenship | 0.26 | 0.037 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uygur, A.; Sevin, H.D.; Yayla, O.; Topaçoğlu, O. The Effect of Eco-Recreational and Environmental Attitudes on Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310660

Uygur A, Sevin HD, Yayla O, Topaçoğlu O. The Effect of Eco-Recreational and Environmental Attitudes on Environmental Behavior. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310660

Chicago/Turabian StyleUygur, Akyay, Halise Dilek Sevin, Ozgur Yayla, and Orhun Topaçoğlu. 2025. "The Effect of Eco-Recreational and Environmental Attitudes on Environmental Behavior" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310660

APA StyleUygur, A., Sevin, H. D., Yayla, O., & Topaçoğlu, O. (2025). The Effect of Eco-Recreational and Environmental Attitudes on Environmental Behavior. Sustainability, 17(23), 10660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310660