Impact of Gentrified Rural Landscapes on Community Co-Build Willingness: The Differentiated Mechanisms of Immigrants and Local Villagers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Rural Gentrification and Gentrified Landscapes

2.2. Rural Community Building

2.3. Co-Build Willingness and Its Differences Among Groups

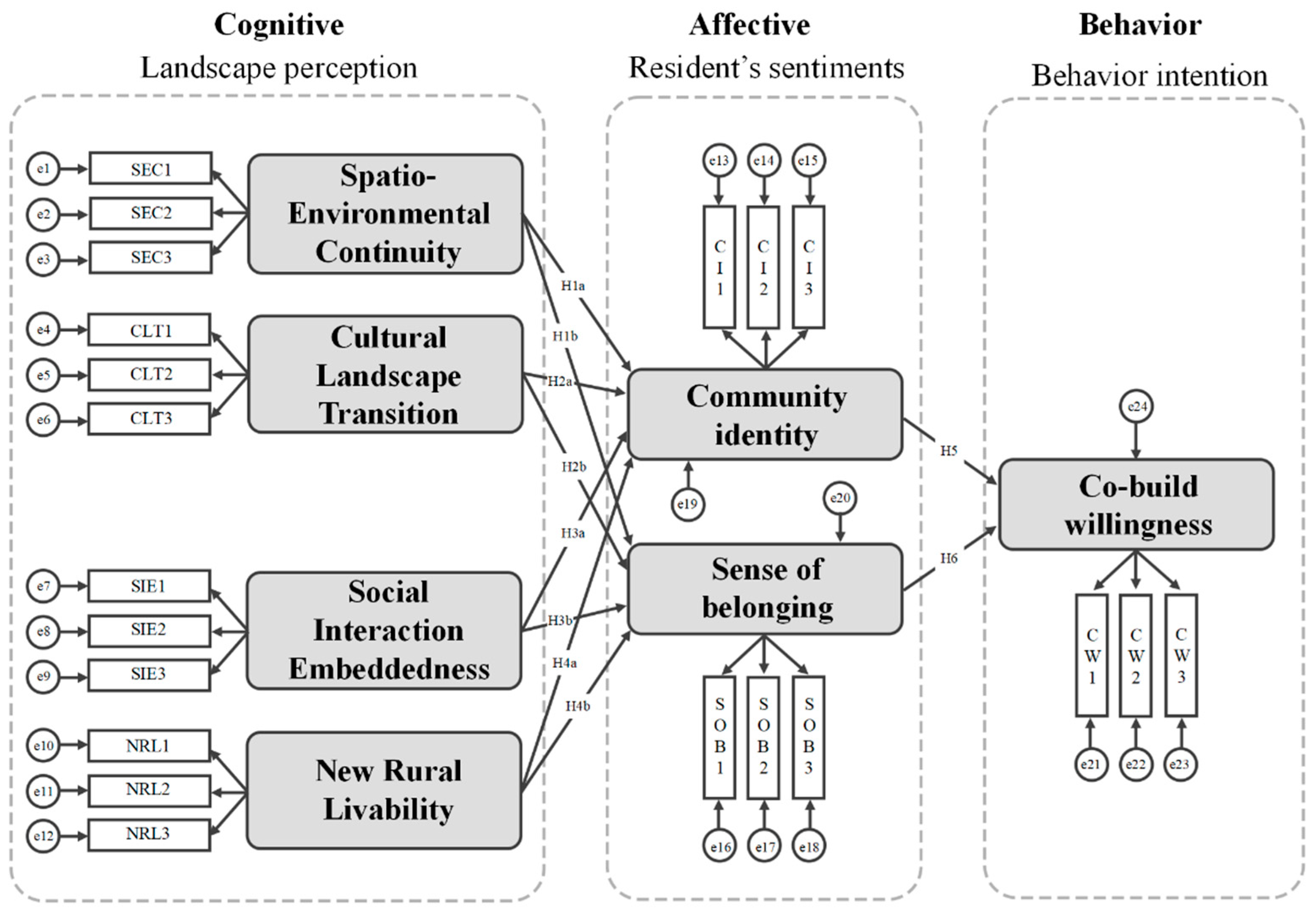

2.4. Research Hypothesis

2.4.1. Spatial–Environmental Continuity

2.4.2. Cultural Landscape Transition

2.4.3. Social Interaction Embeddedness

2.4.4. New Rural Livability

2.4.5. Community Identity

2.4.6. Sense of Belonging

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

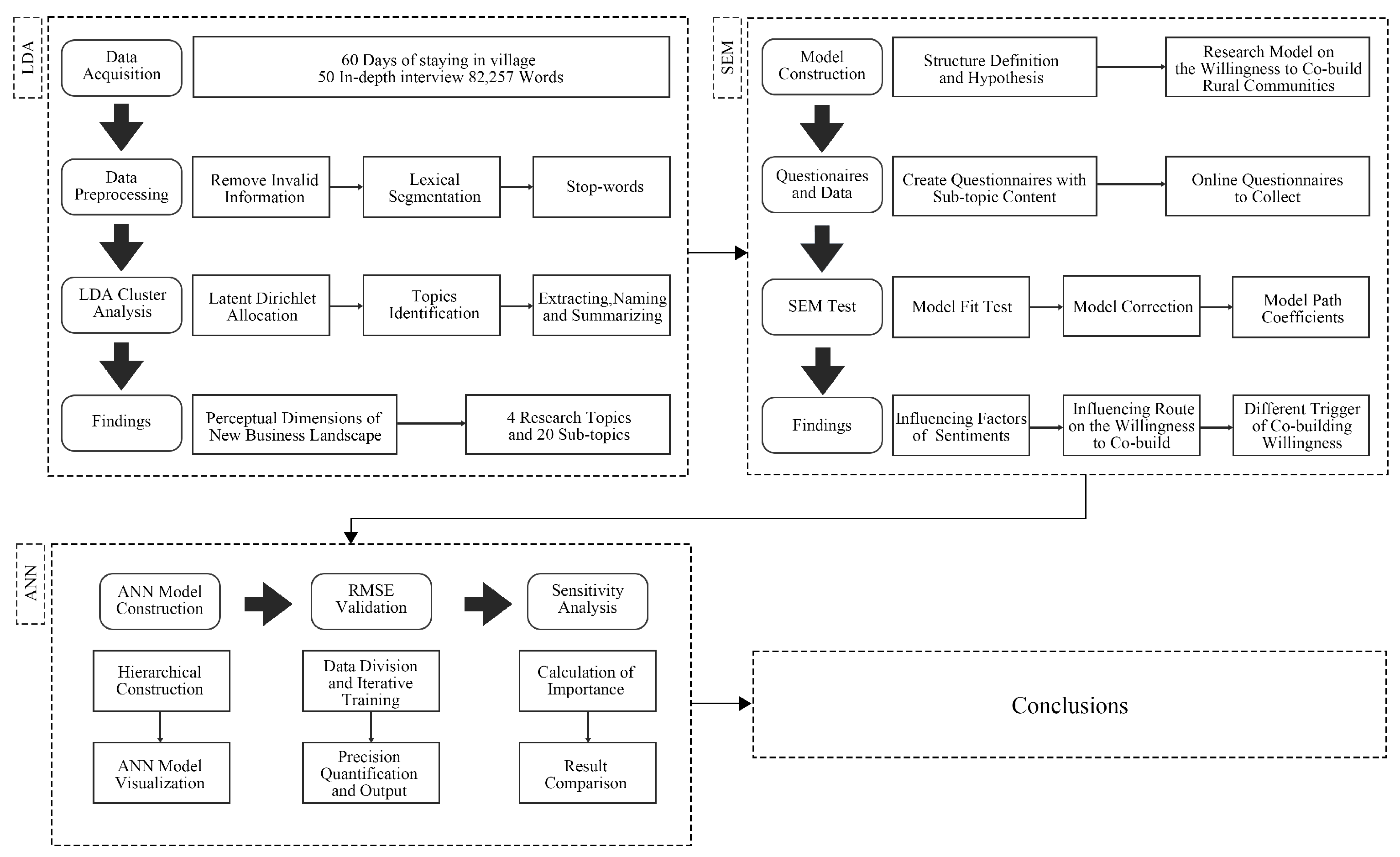

3.2. Data Analysis

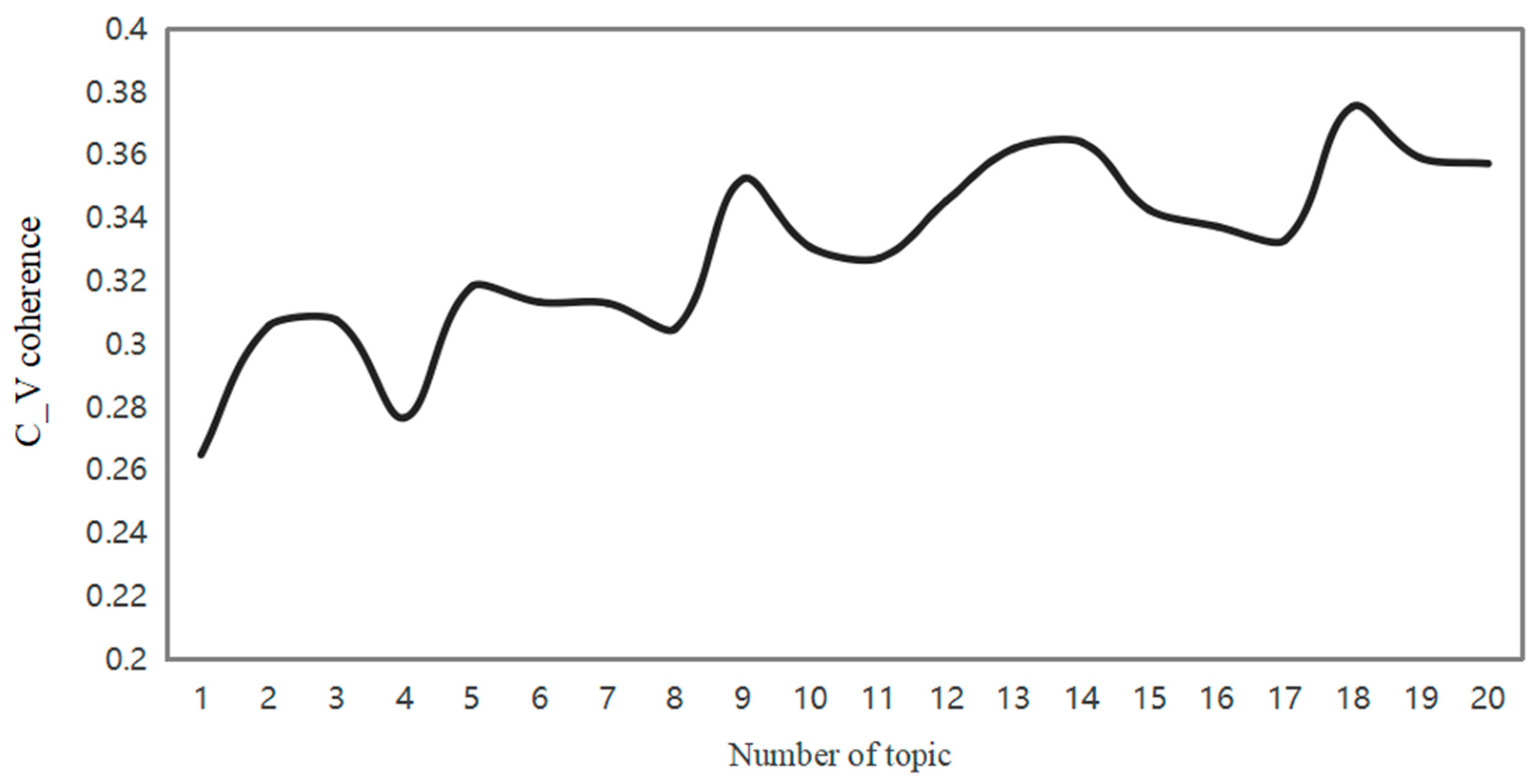

3.3. LDA Topic Modeling Analysis

3.4. Questionnaire Design

3.5. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. The Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

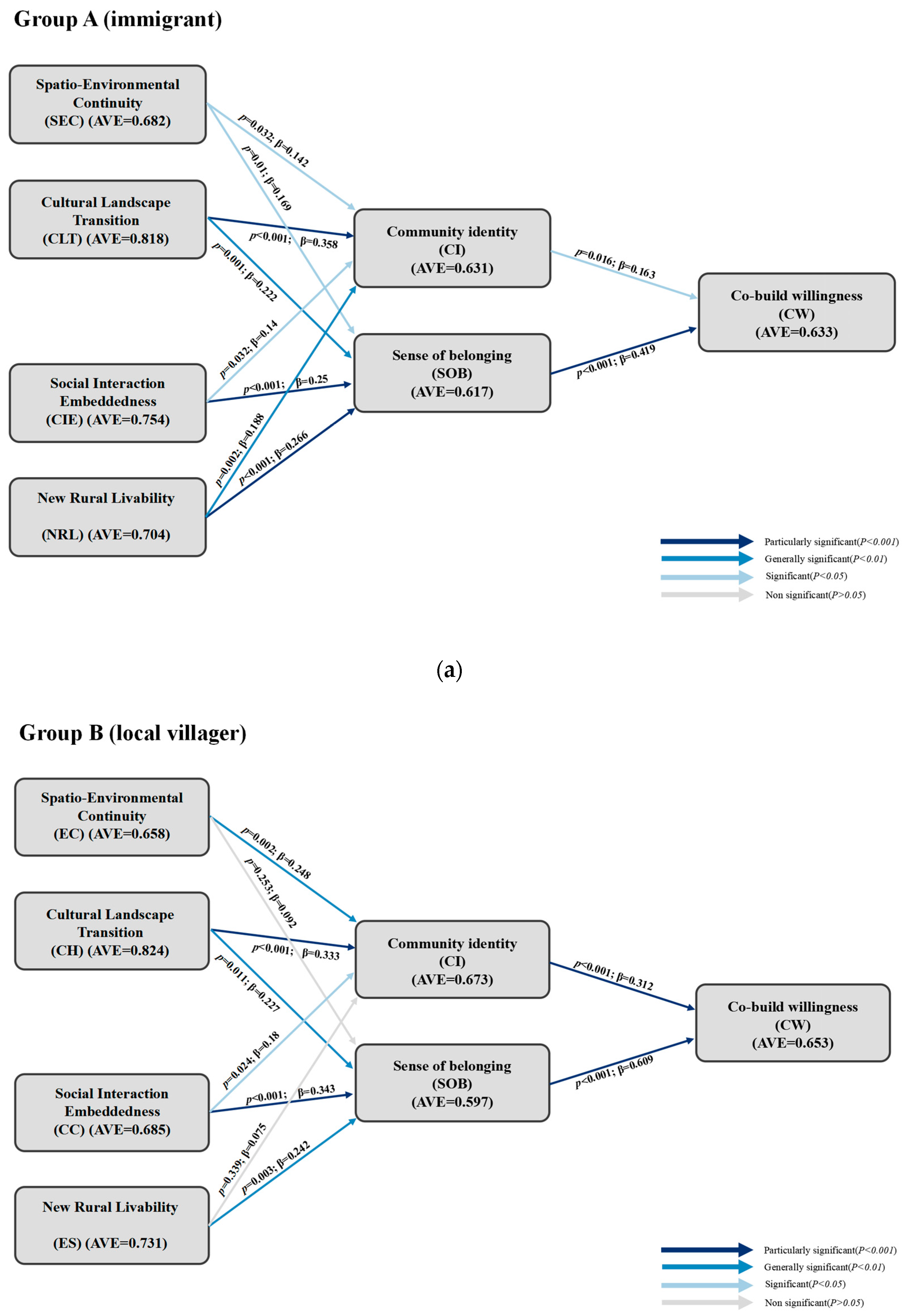

4.3. Moderating Effect Test

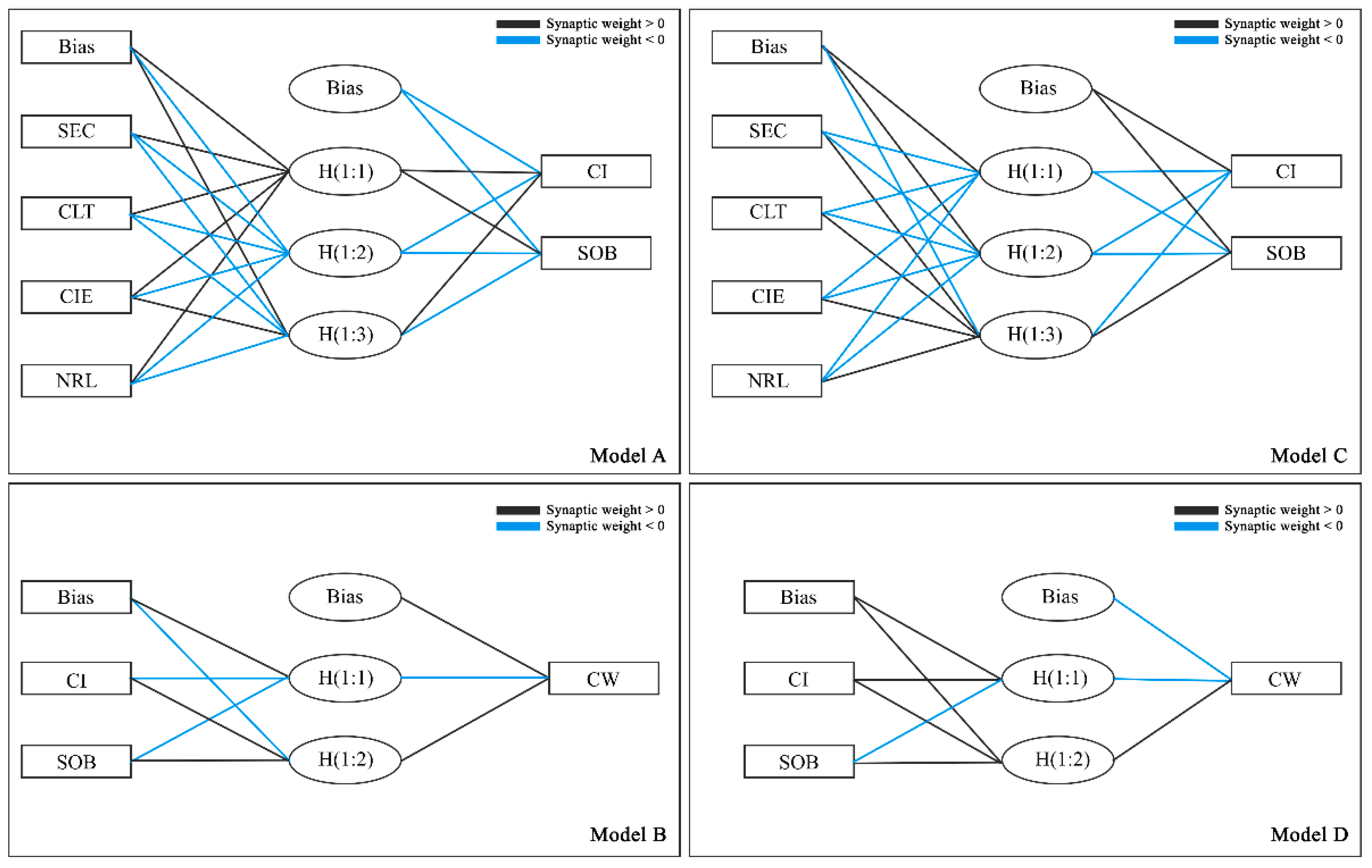

4.4. Construction of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Model

4.5. Root Means Square Error Validation

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Verification of the Impact Mechanism of Gentrified Landscapes

5.2. Differentiated Approaches to the Rural Co-Build Willingness

5.3. Policy Suggestions

5.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Needs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Ye, S. Rural settlement of urban dwellers in China: Community integration and spatial restructuring. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerlund, U.; Sandberg, L. Stories of lifestyle mobility: Representing self and place in the search for the ‘good life’. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 16, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, J.; Amnå, E. Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 2012, 22, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Harlan, S.L.; Bolin, B.; Hackett, E.J.; Hope, D.; Kirby, A.; Nelson, A.; Rex, T.R.; Wolf, S. Bonding and bridging: Understanding the relationship between social capital and civic action. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 24, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPC Central Committee, S.C. Some Opinions on Promoting the Construction of New Socialist Villages. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2006-02/21/content_205958.htm (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Ministry of Agricuture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions of the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on the Development of ‘Beautiful Villages’ Creation Programm. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/tzgg_1/tz/201302/t20130222_3223999.htm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ministry of Agricuture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Implementing the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/zhnyzxd/zcfg/zybs/zyzc/202412/t20241203_6467389.htm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Bosworth, G. Commercial counterurbanisation: An emerging force in rural economic development. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 966–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xie, S.; Knight, D.W.; Teng, S.; Liu, C. Tourism-induced landscape change along China’s rural-urban fringe: A case study of Zhangjiazha. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Duncan, T.; Thulemark, M. Lifestyle mobilities: The crossroads of travel, leisure and migration. Mobilities 2015, 10, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. The Chinese new middle class and their production of an ‘authentic’rural landscape in China’s gentrified villages. Geoforum 2023, 144, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.P.; Kidger, J.; Hickman, M.; Le Gouais, A. The role of emotion in urban development decision-making: A qualitative exploration of the perspectives of decision-makers. Health Place 2024, 89, 103332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. London: Aspects of Change; MacGibbon & Kee: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. The production, symbolization and socialization of gentrification: Impressions from two Berkshire villages. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2002, 27, 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Other geographies of gentrification. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004, 28, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Gentrification and landscape change. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2018; pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, H.E. Capturing rural gentrification. Landsc. Res. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A. Picturing gentrification: Co-producing affective landscapes in an agrarian locale. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; He, S.; Liu, L. Aestheticisation, rent-seeking, and rural gentrification amidst China’s rapid urbanisation: The case of Xiaozhou village, Guangzhou. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. When guesthouse meets home: The time-space of rural gentrification in southwest China. Geoforum 2019, 100, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, L. Unraveling the dynamics of bed and breakfast clusters development: A multiscale analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 169, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, T. Community and Society; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Tonnies, F.; Loomis, C.P. Community and Society; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, F. Studien zu Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Guo, X. A conceptual model of community participation of middle-aged and older people based on interview data from China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Wu, Y.; MacLachlan, I.; Zhu, J. The role of social capital in the collective-led development of urbanising villages in China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 3335–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X. Towards a communication ecology in the life of rural senior citizens: How rural public spaces influence community engagement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Miao, Y.; Li, M.; Ding, X.; Wang, C.; Dou, W. Theoretical development model for rural settlements against rural shrinkage: An empirical study on Pingyin county, China. Land 2022, 11, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chou, R.-J.; Zhu, R.; Chen, S.-H. Experience of community resilience in rural areas around heritage sites in Quanzhou under transition to a knowledge economy. Land 2022, 11, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-C.; Peng, S.-H. Using analytic hierarchy process to examine the success factors of autonomous landscape development in rural communities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.; Sun, N.; Chu, Y.; Chen, H. The influence mechanism of community-built environment on the health of older adults: From the perspective of low-income groups. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengerer, F. Local community participation of older village residents: Social differences and the role of expectations. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 115, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Steiner, G.A. A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.P.; Liebert, D.; Larkin, K.W. Community identities as visions for landscape change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Pedroli, B. Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I. Relationships between personal and collective place identity and well-being in mountain communities. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurgó, B.; Smith, M.K. Cultural heritage, sense of place and tourism: An analysis of cultural ecosystem services in rural Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Li, Z. Tourists’ perceived restoration of Chinese rural cultural memory space. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, M.; Vetter, S.; Wiersum, K.F. From universal to local: Perspectives on cultural landscape heritage in South Africa. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonzaaier, C.; Wels, H. Juxtaposing a cultural reading of landscape with institutional boundaries: The case of the Masebe Nature Reserve, South Africa. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzer, M.; Schofield, J. People and places: Towards an understanding and categorisation of reasons for place attachment–case studies from the north of England. Landsc. Res. 2024, 49, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M. Rural social entrepreneurship: The role of social capital within and across institutional levels. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickes, R.; Zahnow, R.; Corcoran, J.; Hipp, J.R. Neighbourhood social conduits and resident social cohesion. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Zhou, G. Gentrifying rural community development: A case study of Bama Panyang River Basin in Guangxi, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1321–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, J. Chinese rural residents’ identity construction with tourism intervention. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 51, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, D.; Jiao, T.; Wu, W.; Wu, H.; Lu, Y. The dynamic interactive influence of community identity, being accepted by others, and life satisfaction among relocated residents for poverty alleviation in China. Cities 2024, 150, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y. Social participation of migrant population under the background of social integration in China—Based on group identity and social exclusion perspectives. Cities 2024, 147, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E.; Artemi, S.; Borghi, P.; Grohmann, D. Role of local action groups in improving the sense of belonging of local communities with their territories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Roy, M.; Michallet, B.; St-Hilaire, F.; Maltais, D.; Généreux, M. Associations between resilience, community belonging, and social participation among community-dwelling older adults: Results from the eastern townships population health survey. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2422–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Fattah, S.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2010, 5, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, R.E. The declaration of Helsinki. Oxf. Textb. Clin. Res. Ethics 2008, 21, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Hasna, M.F.; Aziz, F.A. Integrating LDA thematic model, FCE, and QFD methods for consumer-centered visual planning of the creative tourism destination: A macrosystem decision approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 177, 113299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Study on the conservation and renewal of traditional rural tourism spaces: A perspective based on tourists’ revisit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 499, 145184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Atik, M. Rural planning guidelines for urban-rural transition zones as a tool for the protection of rural landscape characters and retaining urban sprawl: Antalya case from Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Maliki, N.Z.B.; He, C.; Bi, Y.; Yu, S. Cultural gene characterization and mapping of traditional tibetan village landscapes in Western Sichuan, China. NPJ Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, S. Interpretation of Sustainable Spatial Patterns in Chinese Villages Based on AHP-GIS-FCE: A Case Study of Chawan Village, East Mountain Island, Taihu Lake, Suzhou. Buildings 2025, 15, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, J. Cultural reinvention or cultural erasure? A study on rural gentrification, land leasing, and cultural change. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, W. Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces. Land 2025, 14, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tao, W. The revival and restructuring of a traditional folk festival: Cultural landscape and memory in Guangzhou, South China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhong, D.; Liu, J.; Liao, Z. B&B accommodation entrepreneurship in rural China: How does embeddedness make a difference? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, D.; Duan, X. The impact of multiplex relationships on households’ informal farmland transfer in rural China: A network perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 112, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, D.; Wu, M. Rural tourism as a catalyst for labor return? A rethinking of return migration from a mixed embeddedness perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2026, 39, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H. A socio-spatial exploration of rural livability satisfaction in megacity Beijing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiao, L.; Wang, Q.; Karácsonyi, D. Towards the evaluation of rural livability in China: Theoretical framework and empirical case study. Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Su, W. When hosts meet guests: Local residents’ identity construction amidst rural tourism gentrification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2025, 112, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, S.; Li, Q. “It is my place”: Residents’ community-based psychological ownership and its impact on rural tourism participation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1303–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The use of heritage in the place-making of a culture and leisure community: Liangzhu Culture Village in Hangzhou, China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2024, 30, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Lan, J.; Zhang, G. Sense of belonging and social identity on the settlement intentions of rural-urban migrants: Evidence from China. Ciência Rural 2019, 49, e20190979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Cai, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z. Exploring heterogeneous paths of social integration of the floating population in the communities in Guangdong, China. Cities 2025, 163, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Enhancing Villager Participation in Remote Rural China Through the Co-Creation of ‘Small Gardens’: A Case Study of Hongtang Village. Plan. Theory Pract. 2025, 26, 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, H. Relative Deprivation and Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Village Governance: Evidence from Land Expropriation in Rural China. Asian Surv. 2021, 61, 917–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Koohang, A. An SEM-ANN approach-guidelines in information systems research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2024, 65, 706–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleg, M.; Watson, G.B.; Salheen, M.A. The path to resilience: Change, landscape aesthetics, and socio-cultural identity in rapidly urbanising contexts. The case of Cairo, Egypt. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction a Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 287–318. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Guo, J.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Restoring residents’ place attachment in long term post-disaster recovery: The role of residential environment, tourism, and social and cultural capital. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinke, L.; Rammelmeier, M. The impact of people’s creativity and networks on spatial localisation-Locals, multi-locals, newcomers or returnees as an opportunity for civic engagement in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 113, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, S.; Grant, R. Belonging, identity and place: Middle-class Tasmanian rural young people in urban university. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 103, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Salma, J.; Hegadoren, K.; Meherali, S.; Kolawole, T.; Díaz, E. Sense of community belonging among immigrants: Perspective of immigrant service providers. Public Health 2019, 167, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herslund, L. Everyday life as a refugee in a rural setting–What determines a sense of belonging and what role can the local community play in generating it? J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimermann, M.; Kordel, S. International lifestyle migrant entrepreneurs in two new immigration destinations: Understanding their evolving mix of embeddedness. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perceptual Dimensions | Including Dimensions | Topic Name | Theme Keywords (English Version) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial–environmental continuity | Topic 4 | Environmental aesthetics enhancement | Environment, space, beauty, village, main, feature, guests, courtyard, been there, two years |

| Topic 6 | Reconstruction of Rest Areas | Business, young people, hours, tourists, space, no, children, B&B, village, products | |

| Topic 14 | Ecological landscape restoration | Space, tourists, courtyard, rest, nature, doorway, Double Ninth Festival, construction, B&B, elderly people | |

| Topic 15 | Farmland Landscape Experience | Utilize, cultivate, environment, assist, entrance, villagers, construction, main, several, dance troupe | |

| Topic 16 | Children’s play area layout | villagers, village, food and drink, farming, children, aesthetic sense, what are you doing, rice fields, perspective, photography | |

| Cultural landscape transition | Topic 7 | Cultural symbol dissemination | Tourists, role, environment, viral popularity, impact, opinion, reason, choice, merchants, whether |

| Topic 8 | Festive activities continuing | ordinary people, every day, support, carry out, unable to, real, ability, square, Chongyang Festival, every year | |

| Topic 12 | Space function conversion | Impression, guest, tourist, every day, location, use, B&B, school, small, substitute | |

| Topic 17 | Traditional business model renewal | Issues, B&B, Children, Business model, Tradition, Space, Cultural tourism, Business, Children, Catering | |

| Social interaction embeddedness | Topic 1 | Intergroup interaction | Tourists, less than, restaurants, ordinary people, contact, B&Bs, many, children, between, experience |

| Topic 5 | Youth Entrepreneurship Development Activities | B&B, experience, hope, young people, service, outside world, sometimes, organize, others, participate | |

| Topic 9 | Collaboration among diverse groups | Construction, tourists, B&Bs, operational standards, villages, characteristics, groups, infrastructure, residents, experience | |

| Topic 13 | Public affairs collaboration | B&B, Help, Work, Services, Government, Operational Level, Construction, Outdoor, Research, Stories | |

| Topic 18 | Neighborhood relations | B&B, questions, characteristics, normal, villagers, impressions, hopes, opinions, village, common people | |

| New rural livability | Topic 2 | Life services adaptation | Villagers, tourists, face, need, consumption, issues, operational level, investment, village, daily |

| Topic 3 | Optimization of residential facilities | B&B, environment, problems, hopes, desires, facilities, ordinary people, very large, opening a shop, three years | |

| Topic 10 | Business Policy Support | Environment, publicity, preliminary work, local residents, guests, operations, renovation, assistance, children, updates | |

| Topic 11 | Rural innovation and employment attraction | B&B, space, attraction, issues, characteristics, villagers, young people, entrepreneurship, tourists, interviews |

| Variable Dimension | Measurement Items | Indicator Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial–environmental continuity | Diversified environmental features | Measure respondents’ perception of the visual harmony between traditional and modern landscapes. | Balta, Sıla, and Meryem Atik (2022) [57] Fan, Ding et al. (2025) [58] Wang, Lei et al. (2025) [59] |

| Composite spatial functions | Representing the adaptability of public space renovations to accommodate different needs | ||

| Social service levels | Measuring the dual capacity of public service facilities to meet basic and quality needs | ||

| Cultural landscape transition | Cultural symbol translation | Measuring the acceptance of traditional cultural elements transformed into modern consumer symbols | Zhao, Jiexiang and Zhu, Jiangang (2025) [60] Li, Peiyuan, and Wencui Zhang (2025) [61] Chen, Huiling, and Wei Tao (2017) [62] |

| Consumption scenario iteration | Measuring the innovative appeal of the transition from traditional business models to cultural and tourism experience-oriented scenarios. | ||

| Dynamic Revitalization of Traditional Festivals | Measuring the level of participation and sense of belonging in traditional festive activities within communities | ||

| Social interaction embeddedness | Interaction between cross-groups | Reflecting the intensity of interaction between immigrants and villagers in a gentrified landscape | Liu, Jun et al. (2023) [63] Fang, Tingting et al. (2024) [64] Wang, Xinrui, Dandan Huang, and Meiling Wu (2026) [65] |

| Immigrant Community Development | Measuring the depth of integration of new immigrant groups into local social networks | ||

| Neighbor Relations Adjustment | Measuring the level of neighborhood adaptability of new and old residents caused by spatial changes | ||

| New rural livability | Inclusiveness of consumer services | Reflecting the accuracy of the match between consumer services and residents’ needs | Pang, Yuxin, Wenxin Zhang, and Huaxiong Jiang (2024) [66] Li, Yurui et al. (2020) [67] |

| Optimization of residential facilities | Measuring the degree of satisfaction with the compatibility of modern facilities with the local environment | ||

| Rural Innovation and Employment Attraction | Measuring the strength of the attraction of the gentrified landscape to local talent | ||

| Community identity | Cultural subjectivity perception | Reflecting resident’s shared sense of belonging to the core values of community culture | Ma, Xiaolong, Yiyuan Zhao, and Weifeng Su (2025) [68] Guan, Jingjing et al. (2025) [69] Zhang, Yingchun (2024) [70] |

| Consensus on community values | Assess the strength of identification with core community values | ||

| Collective dignity maintenance tendency | Detect behavioral intentions to actively maintain community image and collective dignity | ||

| Sense of belonging | Emotional anchoring depth | Measuring the strength of residents’ sense of belonging to a specific community space | Liu, Zhen et al. (2019) [71] Liao, Liao et al. (2025) [72] Chen, Peipei, Min Zhang, and Ying Wang (2023) [11] |

| Perception of community acceptance | Assessing individuals’ sense of recognition and inclusion in community social networks | ||

| Long-term attachment | Assess residents’ psychological tendency to view the community as a long-term place of residence. | ||

| Community co-build willingness | Tendency to environmental creation | Reflecting residents’ initiative in environmental creation | Long, Ye, Luan Chen, and Xun Li (2025) [73] Yao, Yuting, Shenghua Lu, and Hui Wang (2021) [74] |

| Cultural capital investment | Representative level of resource support for local cultural innovation | ||

| Public affairs involvement | Measuring the intensity of residents’ initiative in community public decision-making and affairs management |

| Demographic Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Villagers’ household registration | Local | 231 | 61.4% |

| Non-local | 145 | 38.6% | |

| Age | 16–25 age | 76 | 20.2% |

| 25–35 age | 90 | 23.9% | |

| 35–50 age | 128 | 34.1% | |

| 50–75 age | 82 | 21.8% | |

| Gender | Male | 208 | 55.3% |

| Female | 168 | 44.7% | |

| Educational level | Secondary school and below | 117 | 31.1% |

| Associate degree | 114 | 30.3% | |

| Bachelor degree | 107 | 28.5% | |

| Master degree | 38 | 10.1% | |

| Occupation | Rural entrepreneur | 84 | 22.3% |

| B&B operator | 48 | 12.8% | |

| Service worker | 76 | 20.2% | |

| Farmer | 62 | 16.5% | |

| Other | 106 | 28.2% | |

| Length of residence | <1 year | 61 | 16.2% |

| 1–3 years | 135 | 35.9% | |

| 3–5 years | 106 | 28.2% | |

| >5 years | 74 | 19.7% |

| Fit Indices | Standard | Group A Results | Group B Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | 1–3 is excellent, 3–5 is good | 1.651 | 1.735 |

| RMSEA | <0.05 is excellent, <0.08 is good | 0.045 | 0.06 |

| NFI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.8 is good | 0.934 | 0.9 |

| IFI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.8 is good | 0.973 | 0.955 |

| CFI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.8 is good | 0.973 | 0.955 |

| Level 1 Indicators | Level 2 Indicators | Group A Results | Group B Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| KMO | 0.820 | 0.882 | |

| Bartlett’s sphericity | spherical test | 1994.331 | 2898.109 |

| df-value | 210 | 210 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Variable Dimension | Measurement Items | Group A α | Group B α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial–environmental continuity | Diversified environmental features | 0.870 | 0.852 |

| Composite spatial functions | |||

| Social service levels | |||

| Cultural landscape transition | Cultural symbol translation | 0.926 | 0.933 |

| Consumption scenario iteration | |||

| Dynamic Revitalization of Traditional Festivals | |||

| Social interaction embeddedness | Interaction between cross-groups | 0.889 | 0.866 |

| Immigrant Community Development | |||

| Neighbor Relations Adjustment | |||

| New rural livability | Inclusiveness of consumer services | 0.852 | 0.890 |

| Optimization of residential facilities | |||

| Rural Innovation and Employment Attraction | |||

| Community identity | Cultural subjectivity perception | 0.791 | 0.863 |

| Consensus on community values | |||

| Collective dignity maintenance tendency | |||

| Sense of belonging | Emotional anchoring depth | 0.827 | 0.821 |

| Perception of community acceptance | |||

| Long-term attachment | |||

| Community Co-build willingness | Tendency to environmental creation | 0.819 | 0.849 |

| Cultural capital investment | |||

| Public affairs involvement |

| Path Relationship | Group A Standard Regression Coefficient | Group A AVE | Group A CR | Group B Standard Regression Coefficient | Group B AVE | Group B CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEC1 <--- SEC | 0.817 | 0.682 | 0.865 | 0.786 | 0.658 | 0.852 |

| SEC2 <--- SEC | 0.836 | 0.817 | ||||

| SEC3 <--- SEC | 0.824 | 0.829 | ||||

| CLT1 <--- CLT | 0.867 | 0.818 | 0.931 | 0.859 | 0.824 | 0.934 |

| CLT2 <--- CLT | 0.926 | 0.941 | ||||

| CLT3 <--- CLT | 0.919 | 0.922 | ||||

| CIE1 <--- CIE | 0.890 | 0.754 | 0.902 | 0.822 | 0.685 | 0.867 |

| CIE2 <--- CIE | 0.867 | 0.768 | ||||

| CIE3 <--- CIE | 0.847 | 0.888 | ||||

| NRL1 <--- NRL | 0.805 | 0.704 | 0.877 | 0.819 | 0.731 | 0.890 |

| NRL2 <--- NRL | 0.848 | 0.871 | ||||

| NRL3 <--- NRL | 0.863 | 0.873 | ||||

| CI1 <--- CI | 0.832 | 0.631 | 0.837 | 0.862 | 0.673 | 0.861 |

| CI2 <--- CI | 0.768 | 0.770 | ||||

| CI3 <--- CI | 0.781 | 0.827 | ||||

| SOB1 <--- SOB | 0.789 | 0.617 | 0.828 | 0.768 | 0.597 | 0.816 |

| SOB2 <--- SOB | 0.802 | 0.795 | ||||

| SOB3 <--- SOB | 0.765 | 0.754 | ||||

| CW1 <--- CW | 0.867 | 0.633 | 0.837 | 0.840 | 0.653 | 0.850 |

| CW2 <--- CW | 0.767 | 0.784 | ||||

| CW3 <--- CW | 0.747 | 0.800 |

| Implicit Variable | Path | Independent Variable | Estimate | S.E. (Standard Error) | C.R. (Critical Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | <--- | SEC | 0.139 | 0.065 | 2.144 |

| CI | <--- | CLT | 0.276 | 0.054 | 5.066 |

| CI | <--- | CIE | 0.119 | 0.056 | 2.142 |

| CI | <--- | NRL | 0.165 | 0.053 | 3.132 |

| SOB | <--- | SEC | 0.161 | 0.062 | 2.581 |

| SOB | <--- | CLT | 0.168 | 0.052 | 3.241 |

| SOB | <--- | CIE | 0.209 | 0.054 | 3.846 |

| SOB | <--- | NRL | 0.228 | 0.051 | 4.426 |

| CW | <--- | CI | 0.168 | 0.07 | 2.404 |

| CW | <--- | SOB | 0.442 | 0.075 | 5.859 |

| Latent Variable | Path | Independent Variable | Estimate | S.E. (Standard Error) | C.R. (Critical Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | <--- | SEC | 0.259 | 0.086 | 3.031 |

| CI | <--- | CLT | 0.262 | 0.071 | 3.701 |

| CI | <--- | CIE | 0.16 | 0.071 | 2.252 |

| CI | <--- | NRL | 0.066 | 0.069 | 0.956 |

| SOB | <--- | SEC | 0.09 | 0.079 | 1.144 |

| SOB | <--- | CLT | 0.168 | 0.066 | 2.536 |

| SOB | <--- | CIE | 0.288 | 0.069 | 4.148 |

| SOB | <--- | NRL | 0.201 | 0.066 | 3.023 |

| CW | <--- | CI | 0.294 | 0.067 | 4.422 |

| CW | <--- | SOB | 0.609 | 0.083 | 7.314 |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input: SEC, CLT, CIE, NRL | Input: CI, SOB | Input: SEC, CLT, CIE, NRL | Input: CI, SOB | |||||

| Output: CI, SOB | Output: CW | Output: CI, SOB | Output: CW | |||||

| Neural network | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing |

| ANN1 | 0.169 | 0.179 | 0.157 | 0.181 | 0.184 | 0.163 | 0.104 | 0.105 |

| ANN2 | 0.177 | 0.207 | 0.165 | 0.117 | 0.190 | 0.180 | 0.116 | 0.093 |

| ANN3 | 0.171 | 0.159 | 0.158 | 0.173 | 0.178 | 0.210 | 0.116 | 0.092 |

| Mean | 0.172 | 0.182 | 0.160 | 0.157 | 0.184 | 0.184 | 0.112 | 0.097 |

| SD (Standard Deviation) | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Model A | Model B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output: CI, SOB | Output: CW | |||||

| Neural network | SEC | CLT | CIE | NRL | CI | SOB |

| ANN1 | 0.142 | 0.339 | 0.100 | 0.418 | 0.065 | 0.935 |

| ANN2 | 0.262 | 0.379 | 0.025 | 0.333 | 0.489 | 0.511 |

| ANN3 | 0.142 | 0.383 | 0.119 | 0.356 | 0.249 | 0.761 |

| Average relative importance | 0.182 | 0.367 | 0.081 | 0.369 | 0.268 | 0.736 |

| Normalized relative importance (%) | 49.323 | 99.455 | 21.976 | 100.000 | 36.413 | 100.000 |

| Model C | Model D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output: CI, SOB | Output: CW | |||||

| Neural network | SEC | CLT | CIE | NRL | CI | SOB |

| ANN1 | 0.203 | 0.273 | 0.347 | 0.176 | 0.420 | 0.580 |

| ANN2 | 0.175 | 0.286 | 0.363 | 0.176 | 0.436 | 0.564 |

| ANN3 | 0.185 | 0.302 | 0.315 | 0.197 | 0.531 | 0.469 |

| Average relative importance | 0.188 | 0.287 | 0.342 | 0.183 | 0.462 | 0.538 |

| Normalized relative importance (%) | 54.971 | 83.918 | 100.000 | 53.509 | 85.859 | 100.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Z.; Tang, R.; Peng, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Q. Impact of Gentrified Rural Landscapes on Community Co-Build Willingness: The Differentiated Mechanisms of Immigrants and Local Villagers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310613

Guo Z, Tang R, Peng X, Xiao Y, Liang Q. Impact of Gentrified Rural Landscapes on Community Co-Build Willingness: The Differentiated Mechanisms of Immigrants and Local Villagers. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310613

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Zixi, Ruomei Tang, Xiangbin Peng, Yanping Xiao, and Qiantong Liang. 2025. "Impact of Gentrified Rural Landscapes on Community Co-Build Willingness: The Differentiated Mechanisms of Immigrants and Local Villagers" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310613

APA StyleGuo, Z., Tang, R., Peng, X., Xiao, Y., & Liang, Q. (2025). Impact of Gentrified Rural Landscapes on Community Co-Build Willingness: The Differentiated Mechanisms of Immigrants and Local Villagers. Sustainability, 17(23), 10613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310613