What Drives or Hinders Sustainability? Lessons from Organizational Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable Development in Organizations

2.2. Education for Sustainable Development

3. Method

3.1. Study Area and Agents Involved

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection and Procedures

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Semi-Structured Interview Guide

- This guide was developed based on the concepts of Ref. [40] and Ref. [29], who understand the interview as a form of dialogue, in which one party seeks to collect data and the other presents themselves as a source of information. Open-ended questions allow for free response from the interviewee Ref. [41], and some precautions are taken during the interview and the appropriate use of the technique Ref. [42].

- Dear Sir/Madam,

- This research aims to promote corporate sustainability by identifying success stories and failure factors in light of SDGs 4 and 12 within the organization.

- What is the company’s role in corporate sustainability?

- What is employee engagement with sustainability within the company?

- What are the company’s strengths (success stories) in relation to sustainability?

- What are the company’s needs (failure factors) in relation to sustainability?

- What is the company’s current corporate sustainability scenario?

- What are the company’s expectations regarding sustainability?

- What (viable) projects does the company consider essential to implement to foster sustainability?

- Are there any considerations you would like to make that have not been addres

References

- Boiral, O.; Baron, C.; Gunnlaugson, O. Environmental leadership and consciousness development: A case study among Canadian SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, B.J.P.; Siqueira, D.D.; de Barros Camara, R.P.; Paiva, S.B. Responsabilidade Social Corporativa e os Objetivos do Desenvolvimento Sustentável à Luz da Teoria da Legitimidade. ConTexto-Contab. Texto 2023, 23, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Agne Tybusch, F.B.; Silva, P. Desenvolvimento sustentável versus bem-viver: A necessidade de buscar meios alternativos de vida. Opinión Jurídica 2021, 20, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Louche, C. Journeying toward business models for sustainability: A conceptual model found inside the black box of organisational transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Zin, R.M.; Štreimikienė, D.; Yousefpour, A.; Strielkowski, W.; Mardani, A. Aligning the criteria of the green economy (GE) and the sustainable development goals (SDGs) to implement sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoernig, A.M.; Junior, B.A.H. A sustentabilidade ambiental efetivada através da gestão educacional. Rev. Angolana Ciências 2021, 3, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.L.M.; Guerra, E.M.L.; Acosta, R.H.; Delgado, L.H.M. Implementación de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible desde un–Centro de Estudios Universitario. Mendive 2020, 18, 336–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; García-Miguélez, M.P.; Lanero-Carrizo, A. Internal Corporate Social Responsibility for Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuholske, C.; Gaughan, A.E.; Sorichetta, A.; de Sherbinin, A.; Bucherie, A.; Hultquist, C.; Stevens, F.; Kruczkiewicz, A.; Huyck, C.; Yetman, G. Implications for Tracking SDG Indicator Metrics with Gridded Population Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.V.X.D. The Right to Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The principle of interdependence as a parameter for the creation and maintenance of public policies. Rev. La Secr. Trib. Perm. Revis. 2021, 9, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G.C. Sustainable Leadership Practices Driving Financial Performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A.; Clarke, T.; Boersma, M. The governance of corporate sustainability: Empirical insights into the development, leadership, and implementation of responsible business strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolletti, M.; Alem, G.; Fillippi, P.; Bismarchi, L.F.; Blazek, M. Atuação empresarial para sustentabilidade e resiliência no contexto da COVID-19. Rev. Adm. Empres. 2020, 60, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, U.J.; Bessant, J. Sustainable business models: A systematic review of approaches and challenges in manufacturing. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2021, 25, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, H.; Svensson, G.; Rahman, A. “Triple bottom line” as “Sustainable corporate performance”: A proposition for the future. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanga, B.; Groenewald, D. Leveraging effects of triple bottom line business model on the building and construction small and medium-sized enterprises’ market performance. Acta Commer. 2017, 17, a457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, L.C.; Pedrozo, E.A. Transformation for sustainability and its promoting elements in educational institutions: A case study in an institution focused on transformative learning. Rev. Organ. Soc. 2019, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, J.M.; Cayumil Montecino, R.; Sánchez Medina, M. Una aproximación termodinámica para la comprensión de la economía circular aplicada al ámbito minero-metalúrgico. Rev. Medio Ambiente Y Min. 2021, 6, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Programa das Nações Unidas Para o Desenvolvimento-PNUD. 2022. Available online: https://www.br.undp.org/content/brazil/pt/home/about-us.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Organização das Nações Unidas. Transformando Nosso Mundo: A Agenda 2030 Para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável; Organização das Nações Unidas: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://nacoesunidas.org/pos2015/agenda2030/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Sachs, I. Estratégias de Transição Para o Século XXI; Nobel: São Paulo, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Yin, R.K. Estudo de Caso: Planejamento e Métodos; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kashan, A.J.; Mohannak, K.; Perano, M.; Casali, G.L. A Discovery of Multiple Levels of Open Innovation in Understanding the Economic Sustainability. A Case Study in the Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Minayo, M.C.D.S. O desafio da pesquisa social. In Pesquisa Social: Teoria, Método e Criatividade; Ed. Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2010; pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Análise de Dados Qualitativos; Costa, R.C., Ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Iervolino, S.A.; Pelicioni, M.C.F. A utilização do grupo focal como metodologia qualitativa na promoção da saúde. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2001, 35, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo, 3rd ed.; Edições 70: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Caeiro, S. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, T.; Belt, M.V.D.; Denby, L.; Ross, K.; Thwaites, J.; Hawkes, M. Cómo Empezar Con Los ODS en Las Universidade Una Guia Para Las Universidades, Los Centros de Educación Superior y el Sector Académico; SDSN: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, A.C. Métodos e Técnicas de Pesquisa Social, 6th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, C.; Calame, M. Global Pressing Problems and the Sustainable Development Goals/Higher Education in the World: Towards a Socially Responsible University: Balancing the Global with the Local; Global University Network For Innovation (GUNi): Girona, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V. Sustainability as corporate culture of brand for superior performance. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.S.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Lassala, C.; Skare, M. Networking and knowledge creation: Social capital and collaborative innovation in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RocaA-Puig, V. The circular path of social sustainability: An empirical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.; Massini, S.; Malik, K. Benefícios do ensino de colaborações de pesquisa entre universidade e indústria em múltiplas hélices: Em direção a uma estrutura holística. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeyimana, B.S.; Gandhi, J.A.C.; Tiwari, S.; Santos, T.F.; Nair, S.S.G.; Mary, S.; Santos, C.M. Reduzindo lacunas na sustentabilidade: Colaborações entre instituições de ensino superior e indústria para acelerar os ODS. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 529, 146768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Neto, G.C.D.; Pinto, L.F.R.; Amorim, M.P.C.; Giannetti, B.F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.D. Um quadro de ações para uma sustentabilidade forte. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P. An overview of the engagement of higher education institutions in the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyrio, R.D. Métodos e Técnicas de Pesquisa em Administração; Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rudio, F.V. Introdução ao Projeto de Pesquisa Científica; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell, G. Entrevistas individuais e grupais. In Pesquisa Qualitativa Com Texto, Imagem e Som; Bauer, M.W., Gaskell, G., Eds.; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Subcategories | Context Unit | Enumeration | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Success Stories | “…we have our mug to drink our coffee…” “The barrels are used for tables, stools, and pallets as sofas…” | 28 | 45.90% |

| Failure Factors | “…also a PET bottle for water, for the student…” “…collective action for society to adopt outdoor gyms…” | 19 | 52.78% | |

| Social | Success Stories | “Inside the classroom, for students to be aware of the correct waste disposal…” “We participate in clothing campaigns and contribute to the community…” | 22 | 36.06% |

| Failure Factors | “Charitable campaigns, among others, that certainly help many people…” Voluntary actions that we can do, right, to help the municipality…” | 12 | 33.33% | |

| Economic | Success Stories | “…printing of documents is minimal, certificates and communications are all sent by the digital secretariat”. “To form a class, there is a minimum amount; I think that goes a long way regarding financial sustainability, right?” | 11 | 18.04% |

| Failure Factors | “…here we only sell courses on solar panels, but we do not have one here, for example.” “Reusing rainwater… LED lamps, of course, involve an investment issue.” | 5 | 13.88% | |

| Environmental | Economic | Social | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

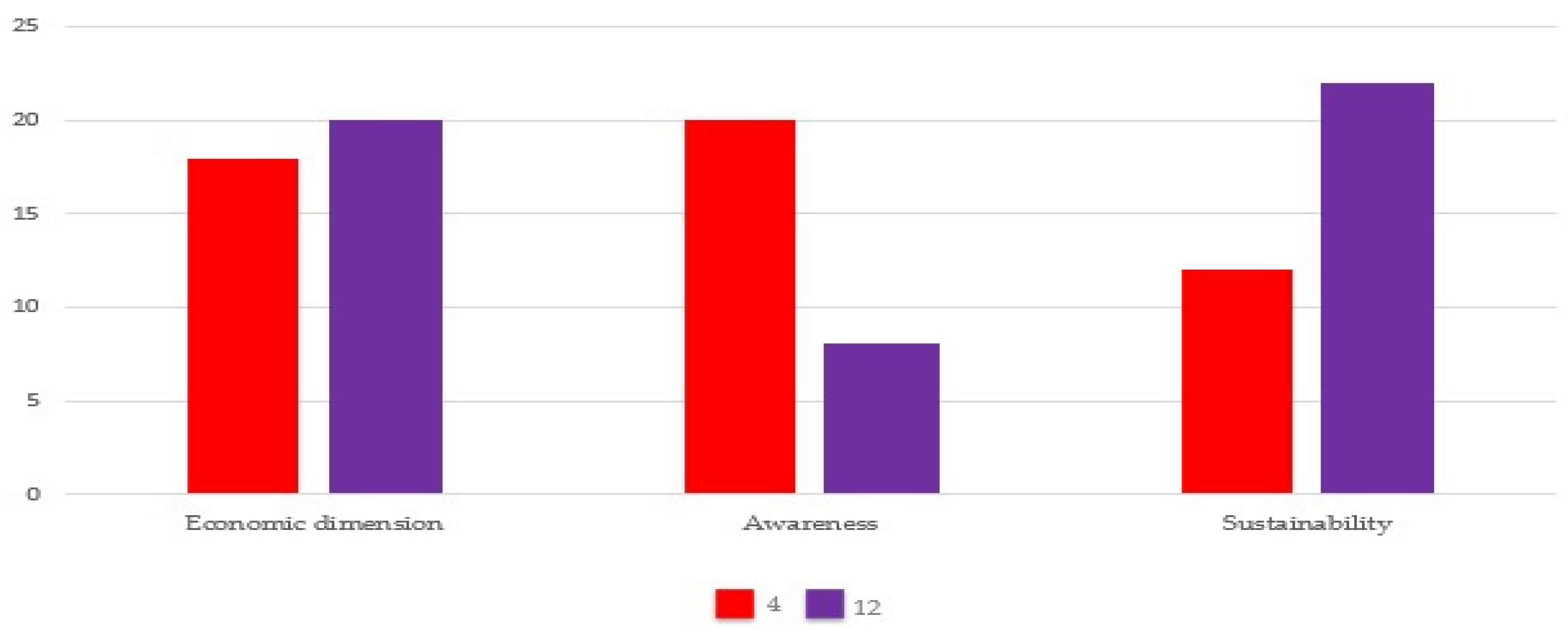

| Economic dimension | 12.00% | 90.00% | 24.24% | 37.18% |

| Awareness | 8.00% | 0.00% | 60.61% | 28.21% |

| Sustainability | 80.00% | 10.00% | 15.15% | 34.62% |

| Total | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dornelles, V.d.C.; Medeiros, D.; Rosa, P.S.; Brandli, L.L.; Ruffatto, J.; Mores, G.; Neckel, A.; Moreno-Rios, A.L.; Dal Moro, L. What Drives or Hinders Sustainability? Lessons from Organizational Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310559

Dornelles VdC, Medeiros D, Rosa PS, Brandli LL, Ruffatto J, Mores G, Neckel A, Moreno-Rios AL, Dal Moro L. What Drives or Hinders Sustainability? Lessons from Organizational Practices. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310559

Chicago/Turabian StyleDornelles, Vaneli do Carmo, Daniela Medeiros, Priscila Souza Rosa, Luciana Londero Brandli, Juliane Ruffatto, Giana Mores, Alcindo Neckel, Andrea Liliana Moreno-Rios, and Leila Dal Moro. 2025. "What Drives or Hinders Sustainability? Lessons from Organizational Practices" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310559

APA StyleDornelles, V. d. C., Medeiros, D., Rosa, P. S., Brandli, L. L., Ruffatto, J., Mores, G., Neckel, A., Moreno-Rios, A. L., & Dal Moro, L. (2025). What Drives or Hinders Sustainability? Lessons from Organizational Practices. Sustainability, 17(23), 10559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310559