1. Introduction

Carbon markets now channel substantial climate finance to smallholders, yet the architecture of those payments—not just whether they are made—shapes land-use outcomes. In the International Small Group and Tree Planting Program (TIST) (

https://program.tist.org/ accessed on 16 October 2025), participating farmers in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and India have been allowed to redirect a portion of their carbon revenues into community assets such as schools, water points, and shared inputs. When farmers combine individual cash with collective benefits, land-use outcomes change markedly: adoption of conservation farming nearly doubles and tree density rises sharply. This paper asks whether payment design itself is a decisive lever for land-use.

Standard protocols (e.g., Verra, Gold Standard) typically institutionalize individual cash transfers on the premise that recipients maximize welfare through private choice, a logic reinforced by Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) and a large body of literature on cash efficacy and program transaction costs [

1,

2,

3]. However, two practical features of agricultural carbon programs raise policy concerns. First, verification lags of 3–5 years create liquidity constraints for farmers between planting and credit issuance. Second, administrative costs scale with dispersed smallholders, stretching program capacity. Together, these frictions can blunt adoption and stall land-use change at scale, particularly in relation to 2030 climate timelines [

4,

5,

6]. If so, the way benefits are packaged—not only their magnitude—may be a decisive lever for accelerating conservation and improving landscape outcomes. In short, payment design can shape land-use outcomes as powerfully as payment magnitude.

We address a specific design gap. The operational field largely treats individual (cash) and collective (community) benefits as substitutes, forcing a binary program choice and limiting innovation in how finance is converted into land-use change. We instead conceptualize payment complementarity: the coordinated use of individual and collective mechanisms to relax distinct constraints—household liquidity and community coordination—thereby enabling super-additive effects on adoption and land-use intensity. Despite rich debates on common-pool governance, accountability, and local capacity [

7,

8,

9,

10], to our knowledge, no studies systematically test, in an operational carbon program, whether combining payment types outperforms either approach alone. Complementarity is therefore a falsifiable design hypothesis: outcomes under mixed mechanisms should exceed a convex combination of single-channel effects if the two channels truly target different bottlenecks.

Our empirical setting is a natural policy laboratory. TIST applies uniform rules for planting, monitoring, and crediting across four countries. Still, since 2008, participating farmers have negotiated alternative arrangements that convert carbon revenues into local public goods either instead of or in addition to cash. We compile the administrative and survey data for 8432 TIST participants and classify realized benefit mechanisms into three mutually exclusive regimes: cash-only, alternative-only, and mixed (cash + community). Alternatives encompass community-facing investments (e.g., classrooms, boreholes, shared tools, seed and fertilizer packages) that are made with documented consent and delivered through established program channels. This within-program heterogeneity permits credible comparisons under a common operational architecture.

We ask three questions. RQ1: Do mixed arrangements exhibit complementarity—effects exceeding those of cash-only or alternative-only on adoption and land-use intensity? If the two payment channels address distinct constraints (household liquidity and community coordination), we should observe super-additive effects under mixed regimes that exceed any convex combination of pure mechanisms. RQ2: Under what organizational conditions do payment innovations emerge and diffuse? We examine whether institutional density thresholds shape the adoption and spread of mixed arrangements, and whether spatial clustering indicates social learning processes. RQ3: Who benefits and what are the broader multipliers? We investigate gender-differentiated outcomes and quantify community-level spillovers to assess whether mixed designs generate returns that extend beyond direct participants. Throughout, we frame the results as associations and probe selection using observable controls and design-based robustness checks.

Our contributions are fourfold. First, we formalize and operationalize payment complementarity as a benefit-design principle for smallholder carbon programs, distinguishing super-additive complementarities from simple convex combinations of single-channel payments and linking the concept to observable outcomes in adoption and land-use intensity. We implement this through a transparent taxonomy (cash-only, alternative-only, mixed) and a program-grounded definition of complementarity. Second, leveraging within-program heterogeneity under a common rule set, we quantify how mixed mechanisms outperform either pure approach across core land-use outcomes, including gender-disaggregated results. Notably, farmers selecting mixed payments are more, not less, financially included, suggesting that their choices reflect strategic alignment of household and community objectives rather than financial exclusion. Third, we identify organizational and spatial conditions under which payment innovation emerges and diffuses, documenting threshold effects in participation and clustering that are consistent with social learning. Fourth, we quantify an effectiveness–efficiency trade-off: mixed arrangements entail roughly four times higher administrative effort than cash-only designs, but they also generate large community multipliers that materially alter cost-effectiveness once spillovers are counted.

For standards bodies and program designers, our findings suggest actionable design principles. Outcome-oriented rules that (i) permit mixed payments within safeguards, (ii) measure and credit spillovers alongside individual outcomes, and (iii) invest in organizational capacity where density is sufficient may substantially increase the land-use impact of climate finance, though causal validation through experimental implementation is needed. Safeguards include transparent negotiation, documented consent, third-party verification of delivery, and straightforward accountability templates to limit elite capture while enabling local experimentation. Reframing household and community aims as complementary policy targets—not competing ones—aligns program operations with how constraints are actually experienced in smallholder settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 situates our argument in the payments, collective action, and institutional innovation literature.

Section 3 develops our theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Section 4 describes the TIST setting, data, and empirical strategy, beginning with program context to establish the identification opportunity before detailing variables and specifications.

Section 5 reports the main and heterogeneous effects.

Section 6 examines mechanisms, thresholds, and scaling constraints.

Section 7 concludes with design guidance for land-use policy and carbon market architecture.

2. Literature Review

This section situates our study within four strands of work and clarifies the gap we fill. We first trace the evolution from price-centric instruments and PES toward implementation-sensitive design, where how payments are structured matters alongside how much is paid. We then review evidence on individual cash transfers—effective on several margins yet rarely compared against alternative mechanisms—and on collective approaches that can solve coordination problems but often depress participation or risk capture when used alone. Building on these, we highlight that the literature largely treats mechanisms as substitutes (cash versus in-kind; individual versus community), leaving untested whether combining channels can deliver super-additive outcomes. We also summarize institutional preconditions for innovation and diffusion—organizational density, leadership, and trust—and note the gendered constraints that shape responses to payment design. Against this backdrop, our study aims to formalize and test payment complementarity using a three-regime taxonomy (cash-only, alternative-only, mixed) within a standardized program, provide operational tests for super-additivity, quantify institutional thresholds and spatial clustering, and document gender-differentiated gains and community multipliers with direct policy implications.

2.1. From Price Instruments to Implementation-Sensitive Design

Market-based instruments and PES programs built on property rights and price signals have structured much of the environmental policy canon [

11]. In carbon markets this logic is operationalized through verified emission reductions (VERs) and standardized, recipient-level cash transfers. Yet agricultural implementation reveals persistent frictions: high transaction and verification costs for dispersed smallholders (30–40% of revenues; [

2]) and the need for continued support beyond initial adoption [

12]. Recent theory and evidence therefore move beyond “how much is paid” to “how payments are structured,” showing that payment timing and mechanism details can change behavioral responses even at similar budget levels [

13,

14]. This evolution motivates our focus on payment design as a lever for land-use outcomes.

2.2. Individual Payments: Strengths and Unresolved Limitations

Individual cash transfers are justified by revealed-preference efficiency and low paternalism, and they often generate measurable welfare and production gains [

1,

3,

15]. However, three limits remain salient. First, most studies compare cash to no payment, rather than to alternative or combined mechanisms, leaving the relative effectiveness unknown. Second, frequency/schedule effects indicate that mechanisms matter beyond price levels. Third, markets value verified co-benefits (e.g., social or biodiversity), as reflected in credit premia [

16], suggesting that purely individual transfers do not always deliver the outcomes buyers seek. Gender evidence further cautions that women’s responses to cash may be constrained by norms and access to assets [

17,

18,

19,

20].

We address these limits by comparing three active regimes (cash-only, alternative-only, mixed) among participants within a single standardized program, holding core operational features constant. This isolates mechanism effects and allows gender-disaggregated assessment (RQs in

Section 4; results in

Section 5).

2.3. Collective Approaches: Promise and Pitfalls

Collective or community-delivered benefits can solve coordination and monitoring problems [

7], align with local institutions [

21], and scale public-goods investments [

22]. Yet replacing individual incentives entirely can depress participation [

23] and invite elite capture [

24]. Crucially, purely collective arrangements may not relax binding, household liquidity constraints that govern day-to-day land-use choices.

Rather than choosing between individual or collective designs, we test whether combining them can dominate both under real operational constraints (RQ1).

2.4. Toward a Synthesis: Payment Complementarity

Binary framings (cash vs. in-kind; individual vs. collective) dominate the literature [

25,

26,

27], leaving unexplored how mechanisms interact when deployed together. Drawing on incentive-combination insights from incentive combination (e.g., super-additivity in multi-channel incentives; [

28]), we define payment complementarity as the coordinated use of individual (liquidity) and collective (coordination/accountability) channels to relax distinct constraints. The testable implication is that mixed mechanisms should outperform a convex combination of single-channel effects on adoption and land-use intensity. We offer (i) an operational taxonomy (cash-only, alternative-only, mixed), (ii) program-grounded definitions of complementarity, and (iii) formal tests for super-additivity (

Section 4 and

Section 5).

2.5. Institutional Preconditions for Innovation and Diffusion

Polycentric governance predicts that local experimentation yields better-fit institutions when enabling conditions are present [

29]. Evidence from carbon pilots and agricultural programs suggests that learning-by-doing is effective, but minimum institutional requirements for more complex designs remain under-specified [

30]. Organizational density, leadership, and trust likely shape whether hybrid arrangements can be negotiated, delivered, and monitored [

31,

32,

33]. Gendered institutions also matter: women’s groups facilitate credible commitment and broaden benefit access [

34,

35].

We quantify institutional correlates of payment innovation, showing spatial clustering and a participation threshold associated with uptake of mixed mechanisms (RQ2;

Section 5), and we examine gender-differentiated outcomes (RQ3).

Table 1 summarizes how our study fills specific gaps across five literature streams. This paper advances the literature on environmental payment design in four ways that directly address the foregoing gaps:

We formalize payment complementarity as a design principle and operationalize it within a standardized program architecture, mapping channels to constraints (liquidity vs. coordination) and deriving testable predictions (RQ1).

Exploiting within-program heterogeneity in TIST across Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and India, we classify realized arrangements for 8432 participants into cash-only, alternative-only, and mixed regimes. Common rules for planting, monitoring, and crediting allow comparisons that focus on mechanisms rather than program idiosyncrasies.

Mixed mechanisms are associated with higher conservation adoption and tree density than either pure regime; formal tests indicate super-additivity (RQ1). Uptake of mixed designs clusters in districts above an organizational participation threshold (RQ2). Gender-disaggregated analysis shows larger gains for women under mixed/alternative benefits and documents large community multipliers (RQ3).

We quantify an effectiveness–efficiency trade-off: mixed designs require greater administrative effort but generate spillovers that materially change cost-effectiveness when credited. We translate these findings into outcome-oriented, safeguard-enabled standards (transparent negotiation, verified delivery, documented consent).

2.6. Conceptual Framework

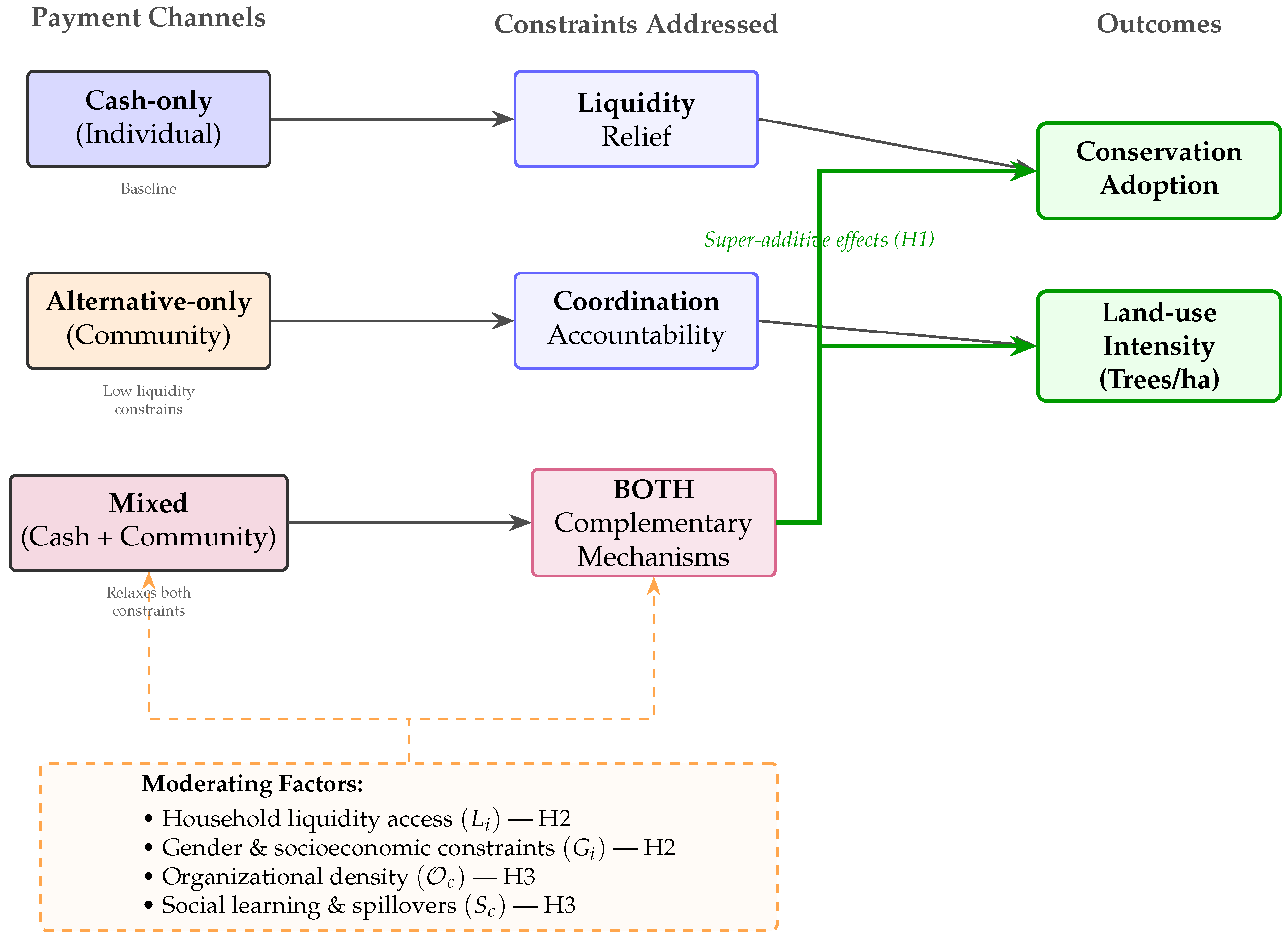

Figure 1 synthesizes our theoretical approach. We distinguish three payment architectures—cash-only, alternative-only, and mixed—each targeting different constraints in smallholder land-use decisions. Cash transfers address household liquidity constraints during the 3–5 year establishment period for agroforestry, enabling upfront investment in seedlings, labor, and inputs. Alternative benefits (community infrastructure, shared resources) address coordination and accountability constraints by creating visible, shared stakes that reduce defection from conservation norms. Mixed arrangements combine both channels, hypothesized to yield super-additive effects when both constraints bind simultaneously.

The framework incorporates three sets of moderating factors that condition the effectiveness of each payment type. First, household-level characteristics (liquidity access, gender, asset holdings) determine the severity of private constraints. Second, community-level factors (organizational density, leadership, social cohesion) govern the feasibility of collective arrangements. Third, institutional context (verification capacity, transaction costs, trust) shapes which payment innovations can be sustained. Our empirical strategy tests whether mixed arrangements dominate pure mechanisms (H1), whether effectiveness patterns align with dual-constraint logic (H2), and whether organizational thresholds enable innovation and diffusion (H3).

3. Theory and Hypotheses

Agricultural carbon programs are shifting from prescriptive, single-channel transfers toward arrangements that participants can co-design. To interpret these innovations, we link three foundational perspectives: (i) household liquidity and intertemporal investment under binding cash-flow constraints (explaining why payment timing/mechanism matters beyond price) [

36]; (ii) collective action and accountability in common-pool settings (explaining why community infrastructure can sustain behavior) [

7]; and (iii) multi-incentive interaction, where combined instruments can yield super-additive responses when they relax distinct frictions [

28]. We use these lenses to formulate three hypotheses that map directly to our research questions.

3.1. H1: Payment Complementarity Increases Adoption and Land-Use Intensity (RQ1)

Prevailing program logic treats individual and collective benefits as substitutes along a single design frontier. In contrast, cash transfers and community benefits target different constraints: the former relax household liquidity over a 3–5 year establishment horizon for agroforestry; the latter build accountability and shared capacity that lower defection from pro-conservation norms [

7,

36]. When deployed together, they form a complementary bundle that can dominate either component alone.

Hypothesis 1. Effectiveness and super-additivity

Let , and let indicators denote cash-only, alternative-only, and mixed (cash + community) regimes. Then,and, more stringently,for any , where is the baseline regime within the program. Operationally, in a saturated model , H1 implies and rejects the convex-combination null via linear restriction tests. 3.2. H2: Complementarity Operates Through Dual Constraint Resolution, with Heterogeneous Gains (RQ3)

Complementarity is not merely an average performance claim; it is a mechanism claim about jointly relaxing liquidity and coordination failures. Cash-only designs leave coordination externalities unaddressed; alternative-only designs can underperform when households lack the buffer to finance adoption costs. Mixed designs should therefore perform best where both constraints bind, with sharper effects among groups facing tighter private constraints (e.g., women or asset-poor households), for whom community infrastructure alone is insufficient.

Hypothesis 2. Mechanisms and heterogeneity—directional

Let measure household liquidity access (e.g., financial inclusion, asset index) and denote salient socioeconomic or gender markers. Then,

Dual-constraint mechanism: The mixed-regime premium relative to alternative-only is larger for low-liquidity households, since mixed designs provide the cash buffer that alternative-only lacks:Meanwhile, the premium relative to cash-only is approximately invariant to liquidity, since both provide cash: Heterogeneous gains: The mixed-regime effect is strictly larger for groups with tighter constraints:where , predicting stronger gains for women, smaller farms, or lower-income households under mixed designs.

Empirically, we implement this via moderated regressions that test whether increases as falls (relative to alternative-only) and whether interactions are positive and larger than or .

3.3. H3: Institutional Thresholds Enable Innovation; Mixed Designs Generate Spillovers (RQ2)

Negotiating, delivering, and monitoring hybrid arrangements requires organizational capacity that simple cash transfers do not. Polycentric governance implies that local experimentation scales when enabling institutions clear a minimum density threshold [

29]. Once mixed designs emerge, they plausibly create spillovers: infrastructure benefits reach non-participants, and demonstration effects shift local norms.

Hypothesis 3. Institutional prerequisites and spillovers

Let be organizational density in community c and the share of mixed arrangements. Then,

- 1.

Threshold for innovation: exhibits a change-point at with for and for (piecewise or spline change-point). This aligns with observed clustering and predicts diffusion where organizational density is sufficiently high.

- 2.

Spillovers to non-participants: For households j with , outcomes increase in : This reflects infrastructure reach and social learning. We expect larger spillovers in places where mixed designs are sustained (i.e., ).

H1 provides the core effectiveness test for RQ1 and embeds the explicit super-additivity restrictions used in

Section 4 and tested in

Section 5. H2 speaks to RQ3 by specifying how mixed payments work (dual-constraint resolution) and for whom (gender and liquidity heterogeneity), implemented via moderated effects and subgroup contrasts. H3 answers RQ2 by positing an institutional change-point for innovation and measurable spillovers to non-participants, motivating spatial clustering tests and local exposure models. Together, these hypotheses translate established theory into operational, falsifiable predictions that our within-program comparisons can evaluate.

Table 2 synthesizes the conceptual framework, showing how payment regimes address specific constraints and map to predicted outcomes.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Program Setting and Identification Opportunity

TIST provides a standardized operational architecture across Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and India: farmers self-organize into small groups, receive uniform training, and undergo annual GPS-verified monitoring of trees. Crucially, variation in payment mechanisms arises from farmer negotiation within this common rule set, initially via bank transfers/cash points, later (post-2007) via mobile money, and, beginning in 2008, through alternative arrangements that convert carbon revenues into local public goods (e.g., classrooms, boreholes, shared inputs) either instead of or in addition to cash. This organic heterogeneity within a uniform operational environment creates a “natural policy laboratory” for testing whether individual and collective benefits behave as substitutes (standard view) or as complements (our theory).

4.2. Data Sources and Sample Construction

We combine administrative program records with a primary survey conducted from January 2022 to September 2023 as part of the SDG Impact assessment. Enumerators implemented structured, face-to-face interviews in local languages. Within 215 districts containing TIST participants, villages were sampled proportionally to enrollment; enumerators targeted full coverage of participants, with supplemental random draws of non-participants to provide village-level context. From 11,529 interviews, we focus on the 8432 enrolled farmers eligible for carbon payments. Administrative records for 576 farmers provide details on alternative arrangements (benefit type; number of community members reached), enabling analysis of both household outcomes and community spillovers. The results generalize primarily to TIST’s Kenyan operations given sample shares (

Table 3).

4.3. Measures and Variable Construction

Payment status is coded from two survey items (cash receipt; other benefits received “instead of” or “in addition to” cash), yielding four mutually exclusive groups: cash-only (52.6%), alternative-only (1.2%), mixed—cash + community (5.8%), and awaiting first payment due to verification lags (40.4%). Unless stated, cash-only is the baseline. The alternative-receiving groups (alternative-only and mixed) collectively enable tests of complementarity.

The primary outcomes are as follows: (i) conservation adoption (binary), defined as practicing ≥3 of minimum tillage, rotation, cover crops, composting, mulching, and agroforestry; (ii) trees per hectare (continuous), computed as monitored trees divided by self-reported farm size. We winsorize trees/ha at the 99th percentile and, in robustness, fit Poisson/negative binomial models to raw counts. We also construct an administrative effort index from program procedures: cash-only receives a baseline score of 1 (standard bank transfer or mobile money); an alternative-only score of 3 (requiring benefit negotiation, procurement, and delivery verification); and a mixed score of 4 (combining cash transfer with alternative benefit coordination). The index reflects procedural steps rather than time expenditure. Cash-only includes (1) payment processing. Alternative-only includes (1) community negotiation, (2) procurement/contracting, and (3) delivery verification. Mixed includes all four steps, though cash and alternative components can be partially parallelized in administration. We interpret this as relative implementation complexity. The index is normalized to [0, 1] for regression analysis by dividing by the maximum score.

The moderators for H2/H3 include liquidity access (financial inclusion, asset index), gender (female), and organizational density at the community/district level (share of households in formal groups; TIST leadership presence). The controls include daily income (log USD), farm size (ha), age, years in TIST, group membership, leadership role, and country/district indicators. Sampling weights (if any) are applied in descriptive statistics; the regression results are unweighted with district fixed effects, and weighted as robustness.

4.4. Empirical Strategy

Our analyses align with the research questions and hypotheses presented in

Section 3: (RQ1/H1) effectiveness and super-additivity; (RQ3/H2) mechanisms and heterogeneity; and (RQ2/H3) institutional thresholds and spillovers.

We first model payment choice via multinomial logit to profile who selects cash-only, alternative-only, or mixed regimes relative to the awaiting/cash baseline:

where

includes

and country dummies. This clarifies whether alternatives target exclusion or reflect strategic choice by better-resourced/organized farmers.

4.4.1. RQ1/H1: Effectiveness and Super-Additivity Tests

We estimate saturated outcome models with district fixed effects:

For adoption we report linear probability and logit marginal effects; for trees/ha, OLS on winsorized levels, and for robustness, Poisson/negative binomial on counts. Super-additivity implies that

tested via linear restrictions (grid over

) and an omnibus

using pairwise Wald tests with Holm–Bonferroni correction.

4.4.2. RQ3/H2: Mechanism and Heterogeneity (Dual Constraints)

We probe liquidity/coordination channels via moderated effects:

where

measures liquidity access and

marks gender/SES. H2 predicts

relative to alternative-only (mixed compensates low-liquidity households) and

(larger mixed gains among women or more constrained groups).

4.4.3. RQ2/H3: Institutional Thresholds and Spillovers

Let

denote organizational density in community/district

c. We estimate a change-point (segmented) model for innovation:

where

, and

is estimated by grid search with bootstrap CIs. We then test spillovers to non-recipients using exposure

(share of mixed in

c):

with

predicted by H3 (infrastructure reach; social learning). Spatial dependence is a key concern given the geographic clustering of alternative payments documented in

Section 5. We address this through three approaches: (i) computation of Moran’s I statistic to quantify spatial autocorrelation in payment mechanisms and outcomes; (ii) standard errors clustered at the village level, which accounts for within-village correlation; and (iii) as a robustness check, Conley [

37] spatial HAC standard errors with distance cutoffs of 50 km and 100 km to allow for cross-village spatial correlation. The results are substantively unchanged across specifications, suggesting that district fixed effects and village clustering adequately capture spatial dependence in our setting.

4.5. Addressing Selection and Identification

Payment choice is endogenous. We triangulate using three complementary strategies:

- (i)

Fixed effects and rich controls

Equation (

9) includes district FE and extensive

to absorb location-specific confounders and farmer heterogeneity.

- (ii)

Design-adjacent matching/weighting

We estimate pairwise propensity scores for (A vs. C) and (M vs. C) using logit on and district FE, implement nearest-neighbor matching with caliper 0.1 SD, and re-estimate effects on matched samples. As a doubly robust alternative, we report inverse-probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA).

- (iii)

Sensitivity to unobservables

Following [

38], we compute coefficient-stability bounds for

and

relative to the cash baseline under plausible

, providing transparent intervals consistent with selection on unobservables. Where relevant, we complement with Altonji–Elder–Taber ratios.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1 [

39]. The key packages included the following:

lfe for fixed-effects regressions with clustered standard errors;

MatchIt for propensity score matching;

WeightIt for inverse probability weighting;

spdep for spatial autocorrelation tests (Moran’s I) and spatial weight matrices;

lmtest and

sandwich for robust inference; and

ggplot2 and

sf for visualization and mapping. Conley spatial standard errors were computed using custom functions based on [

37]. Standard errors were clustered at the village (or group) level throughout; inference was adjusted for multiple hypotheses using Benjamini–Hochberg FDR using the

p.adjust function.

4.6. Data Quality, Missingness, and Ethics

We document item non-response rates and apply listwise deletion for missing treatment or outcome data; the results are robust to inverse probability weighting for missingness. Trees are audited annually via GPS-verified counts; farm size is self-reported (trimmed at 99th percentile; alternative results with median-ratio adjustment). The study protocol followed informed-consent procedures; the analysis uses de-identified records.

Our cross-sectional design estimates associations, not causal dynamics, and payment selection may reflect unobservables (motivation, norms). Administrative-effort measures are indices rather than time-use quantifications. Nonetheless, the within-program variation under a common operational architecture, coupled with fixed effects, matching/weighting, and sensitivity bounds, provides credible evidence on whether and where mixed mechanisms outperform pure designs, and on the institutional conditions under which payment complementarity is most likely to translate into landscape change.

5. Results

5.1. Overview and Linkage to Empirical Models

We organize the results based on the research questions and hypotheses outlined in

Section 3 and estimated using the specifications in

Section 4. First, we report the main effects and super-additivity tests (RQ1/H1) from the saturated model in Equation (

9). Second, we examine mechanisms and heterogeneity (RQ3/H2) using moderated versions of Equation (

9). Third, we quantify institutional thresholds and spillovers (RQ2/H3) with the change-point/logit model in Equation (

12) and exposure regressions for non-recipients. Throughout, we present descriptive contrasts as a prelude to the regression estimates and retain the visual evidence to aid interpretation.

5.2. Main Effects and Super-Additivity

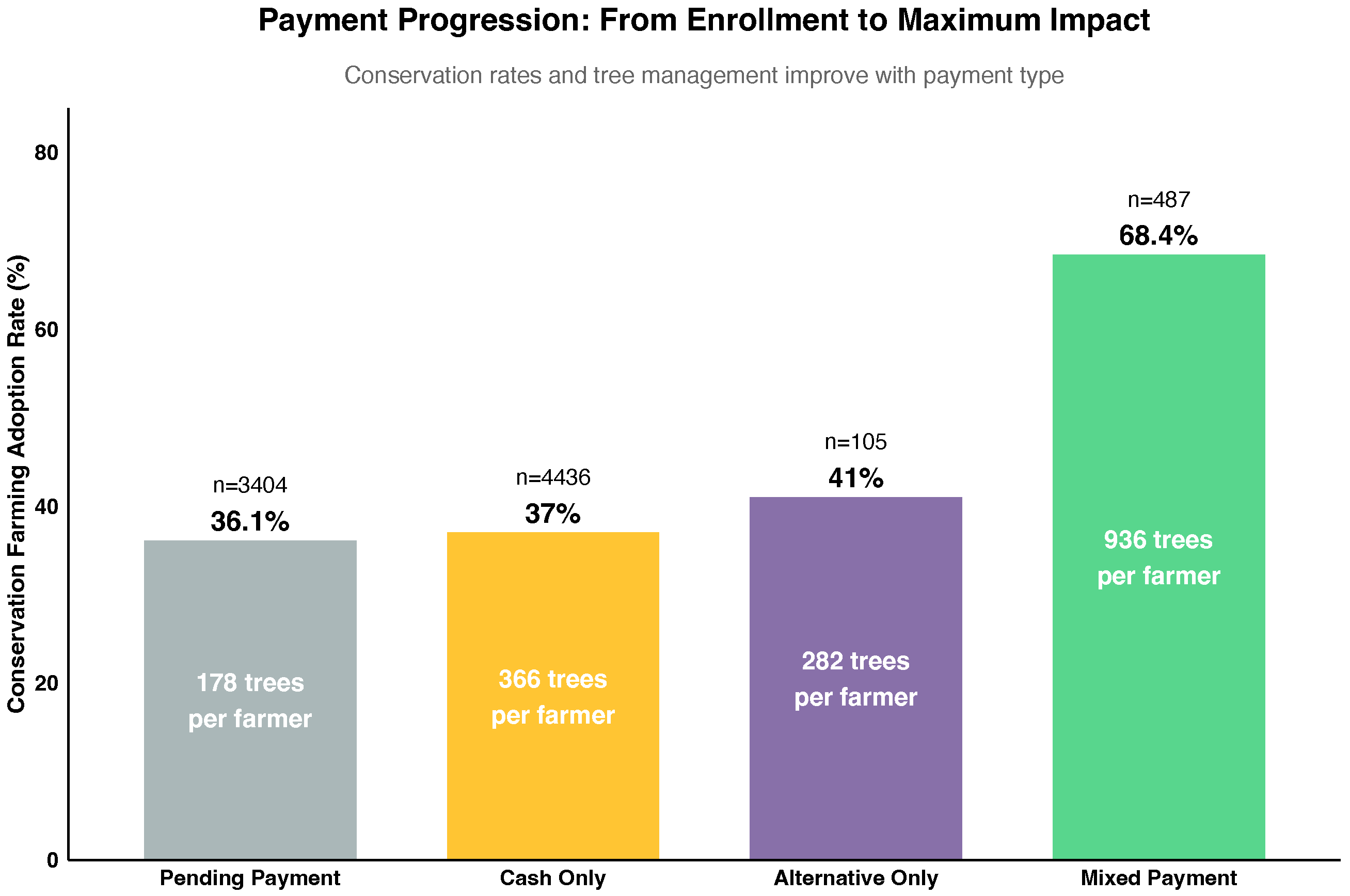

Figure 2 summarizes unadjusted differences across regimes. Farmers receiving cash-only report 36.6% conservation adoption; alternative-only, 41.0%; and mixed (cash + community), 68.4%. Tree management exhibits analogous patterns: cash-only maintains 366 trees/farmer versus 282 under alternative-only and 936 under mixed. Intensification is evident in trees/ha: 215 (cash-only), 115 (alternative-only), and 281 (mixed). These contrasts motivate formal tests under Equation (

9).

Table 4 reports coefficients from Equation (

9). Relative to the cash-only baseline, mixed payments are associated with a 0.274 (s.e. 0.047) increase in conservation adoption when controlling for income, financial inclusion, farm size, and district fixed effects; for intensification, mixed payments are associated with 0.534 (s.e. 0.058) higher log(trees/ha). Alternative-only shows no gain in adoption and a reduction in log(trees/ha). These results corroborate the descriptive pattern with covariate adjustment and location controls.

We test whether mixed exceeds both pure regimes and any convex combination thereof (H1).

Table 5 summarizes linear-restriction F-tests implied by Equation (

9). Mixed significantly exceeds cash, alternatives, and the convex-combination benchmark, supporting complementarity rather than substitution.

5.3. Mechanisms and Heterogeneous Effects

Why does alternative-only underperform? Consistent with H2, alternative-only recipients have substantially lower daily income (USD 1.95) than cash-only (USD 2.74) and mixed (USD 3.56) recipients, suggesting unresolved liquidity constraints that may limit the ability to capitalize on community infrastructure. Mixed arrangements address both liquidity (cash) and coordination/accountability (community), enabling adoption and intensification.

Moderated versions of Equation (

9) show larger mixed-regime gains where liquidity is tighter (financial inclusion

) and among women, consistent with dual-constraint resolution.

Figure 3 illustrates the magnitude: women with alternatives (predominantly in mixed regimes) earn USD 4.22/day and manage 872 trees/farmer versus USD 1.91 and 304 under cash-only regimes. These patterns align with H2’s prediction that mixed designs disproportionately benefit groups facing tighter private constraints.

From a practical standpoint, mixed payment mechanisms present a trade-off between effectiveness and administrative complexity. Per-recipient outcomes are substantially higher for mixed payments (68.4% adoption vs. 36.6% for cash-only; 281 vs. 215 trees/ha), but implementation requires greater coordination capacity for benefit negotiation, procurement, and verification. Each alternative arrangement reaches an average of 167 community members beyond the direct recipient, suggesting that programs crediting community-level outcomes may find mixed mechanisms cost-effective despite higher implementation effort. However, definitive cost–benefit analysis requires comprehensive program cost data that incorporate both administrative expenses and benefit transfer values, which were not available for this study. Programs should pilot mixed mechanisms in settings with sufficient organizational capacity (above the ≈38.9% threshold identified in

Section 5) while collecting detailed cost data to inform scaling decisions.

5.4. Institutional Thresholds, Clustering, and Spillovers

Payment innovations are geographically concentrated. Across 215 districts, only 73 feature any alternative payments; Moran’s

(

) indicates spatial clustering. Estimating Equation (

12) yields an organizational-density change-point around

: below this threshold, the probability of mixed adoption is flat; above it, uptake rises with organizational density, consistent with H3.

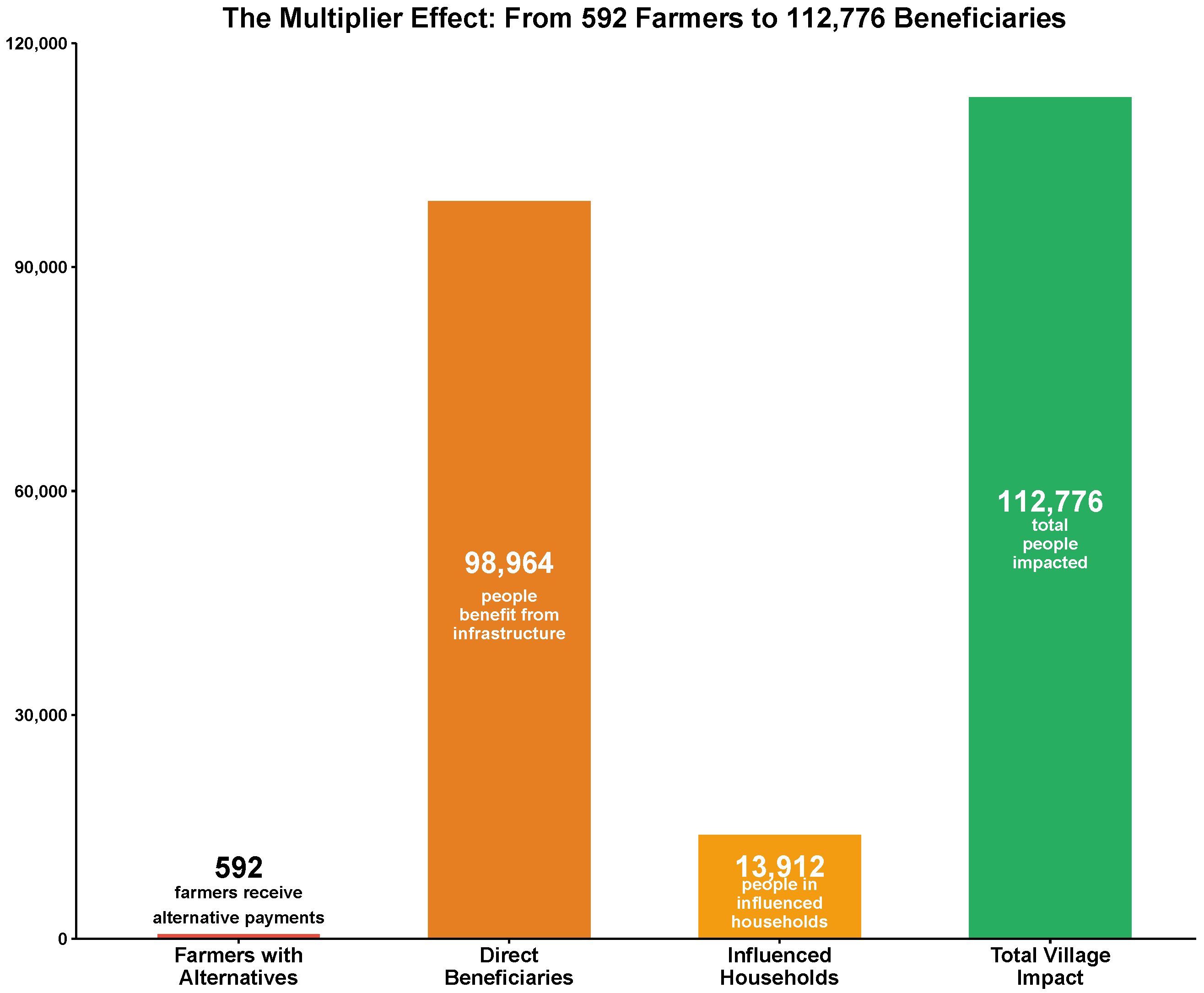

In villages where mixed arrangements exceed 20% of farmers, non-recipients exhibit higher conservation adoption (42.8% vs. 31.6% in cash-dominated villages;

,

). Exposure regressions for non-recipients (

on village share of mixed) yield positive and significant

, indicating spillovers via infrastructure reach and social learning. Aggregating direct beneficiaries (mean 167 persons per alternative arrangement) with spillovers implies a large community multiplier (

Figure 4).

5.5. Administrative Effort and Effectiveness–Efficiency Trade-Off

Mixed arrangements entail higher implementation complexity. Using the program-based effort index (cash-only , alternative-only , mixed ), we document an effectiveness–efficiency trade-off: higher administrative effort accompanies the regimes associated with the largest land-use gains. This supports outcome-oriented standards that permit mixed payments with safeguards and realistic budgeting for delivery and verification.

6. Discussion

Our estimates indicate that mixing individual cash with community benefits is associated with substantively and statistically higher levels of conservation adoption and land-use intensity than either mechanism on its own. Unadjusted contrasts show adoption of conservation farming at 68.4% for mixed recipients compared to 36.6% for cash-only and 41.0% for alternative-only recipients. The average number of trees per hectare is 281 under mixed, compared to 215 for cash-only and 115 for alternative-only. When we move from descriptive differences to the saturated models in Equation (

9), the coefficient on mixed in the log(trees/ha) specification is 0.534 (s.e. 0.058), which corresponds to approximately 70% higher tree density relative to observationally similar cash-only farmers within the same districts. In parallel, the linear probability model implies a 27.4 percent higher probability of conservation adoption for mixed recipients after adjusting for household and location covariates. These results, taken together with the rejection of the convex-combination null across

, are consistent with the super-additivity prediction in H1, namely that two instruments acting on distinct frictions yield outcomes that exceed either instrument alone

The mechanism evidence is consistent with the theory of dual constraint resolution advanced in H2. Our findings suggest that cash transfers may alleviate short-run liquidity and risk constraints that loom large during the three–five year establishment period common in agroforestry systems, while community-delivered infrastructure and services foster the social accountability and coordination required to sustain behavior change. The pattern that alternative-only underperforms on land-use intensity, despite providing public goods, is informative rather than anomalous. Alternative-only recipients have substantially lower daily income than either cash-only or mixed recipients in our data, suggesting that the private liquidity constraint remains binding when cash is fully replaced by community benefits. In other words, the collective mechanism is necessary to generate persistent, visible stakes and shared capacity, but it is insufficient when households cannot finance the transition costs; the mixed bundle addresses both sides of this problem, which explains its superior performance on adoption and trees per hectare without invoking unobserved preferences.

The heterogeneous gains among women reinforce the same mechanism. Women receiving alternatives—predominantly through mixed arrangements—record higher daily incomes and maintain far more trees than women paid cash only, a difference of practical rather than merely statistical significance. These patterns are consistent with binding private constraints that are more difficult for women to overcome, including limited control over household finances, weaker access to inputs and extension services, and higher exposure to idiosyncratic shocks. By preserving a private cash stream while simultaneously installing publicly visible assets negotiated in groups, mixed arrangements operate along two channels that are each individually incomplete for many women. The result is not that community benefits “target women” by design, but that the complementarity of private liquidity and collective provision enlarges the feasible set for groups facing tighter constraints.

Institutional preconditions limit where complementarity emerges and scales. The change-point analysis in Equation (

12) indicates that the probability of adopting mixed arrangements is flat at low levels of organizational density and rises only after a threshold around 0.389 is reached. The observed spatial clustering (Moran’s

,

) is therefore not an artefact of agro-ecology alone, but reflects the presence of capacity to negotiate, deliver, and verify community assets under a carbon standard. Above the threshold, we also observe spillovers to non-recipients: exposure to mixed arrangements within a village is associated with higher adoption even among farmers who did not themselves receive alternatives, an effect consistent with both infrastructure reach and social learning. Together these findings speak directly to H3: innovation in payment architecture is contingent on institutional density, and once present, it propagates land-use change beyond the set of direct recipients.

Two implications follow for how effectiveness might be assessed. First, if spillovers can be verified and attributed to specific arrangements, cost-effectiveness calculations could incorporate per-beneficiary and per-hectare metrics rather than per-direct-recipient measures alone when arrangements measurably create spillovers and community reach. The back-of-the-envelope multiplication from 592 alternative recipients to roughly 112,776 people affected is not an accounting trick but a change in the unit of analysis once infrastructure and demonstration effects are integral to the intervention logic. Second, higher administrative effort in mixed regimes—coordination, verification of asset delivery, documentation of consent—should be interpreted as an input that enables scale through social multipliers, not as deadweight cost. In settings where organizational density is below the threshold, those inputs may be wasteful; where the threshold is exceeded, they are a prerequisite for translating private incentives into landscape-level change.

Finally, the “alternative-only paradox” is better framed as a sequencing problem than a failure of collective provision. Where households face acute liquidity shortages, replacing cash entirely with public goods leaves the private constraint unresolved and can depress intensification even if the public asset is well chosen. This interpretation reconciles our results with the broader collective-action literature: public goods are effective once private feasibility is restored. In practice, programs should expect different payment architectures to be appropriate at different institutional and income levels, with mixed options emerging as the dominant design only when both household and community constraints can be addressed simultaneously.

Our findings on mixed cash–community mechanisms align with, yet are distinct from, three adjacent branches of the literature. First, relative to price-based effects in cash-transfer and PES experiments, our estimates capture associations within a program’s realized options rather than causal responses to randomized prices alone. As such, our super-additivity tests complement those studies by asking whether combining a liquidity instrument (cash) with collective or in-kind benefits shifts outcomes beyond what a convex combination of single-channel effects would predict.

Second, in contrast to collective-benefit-only designs that sometimes underperform due to liquidity constraints or coordination frictions, our mixed architecture appears to relax household-level cash constraints while preserving local public-goods provision and knowledge spillovers, which together can rationalize the observed super-additive association.

Third, mechanism-interaction and co-benefit valuation studies suggest that buyers (and communities) may reward packages that jointly deliver private and verifiable social outcomes. Our evidence is consistent with that perspective: mixed designs are associated with higher adoption and tree density, and we detect diffusion consistent with participation thresholds.

External validity hinges on local institutions, gendered access to resources, and social learning pathways. Our gender-disaggregated patterns suggest that when alternatives are embedded in mixed regimes, women’s productivity gains are comparatively larger, potentially reflecting complementarities between liquidity relief and reduced exposure to binding input or mobility constraints. Program replication should therefore attend to (i) the share of cash vs. community benefits, (ii) safeguards and verification for spillovers, and (iii) the local participation density required for social learning. We outline a phased rollout approach in the Conclusions to accumulate credible evidence on optimal mixes across contexts.

7. Conclusions

This paper advances the literature on environmental payment design by formalizing and empirically testing the notion of payment complementarity in a large, operational program. Three conclusions stand out. First, mixed arrangements are associated with higher conservation adoption and substantially higher trees per hectare than either cash-only or alternative-only mechanisms, and they pass formal tests that rule out simple averaging of component effects. Second, the association between mixed designs and superior outcomes is consistent with a dual-constraint mechanism: cash may ease private liquidity and risk during the transition period, while community assets may supply coordination and accountability that private transfers alone do not provide; these channels appear to function as complements for many households, particularly women. Third, complementarity is not universally available: adoption of mixed designs concentrates above an organizational-density threshold and generates measurable spillovers to non-recipients once present, implying that institutions govern both feasibility and diffusion.

7.1. Policy Recommendations for Carbon Program Design

Our findings suggest three concrete design principles for programs seeking to convert climate finance into durable land-use change:

Recommendation 1: Adopt outcome-based flexibility with procedural safeguards. Carbon standards should permit farmers to negotiate mixed payment arrangements—combining individual cash with community benefits—where institutional capacity permits, rather than mandating uniform cash transfers. However, this flexibility must be paired with safeguards: documented individual consent for benefit conversion, third-party verification of infrastructure delivery, transparent negotiation processes recorded at the group level, and straightforward accountability templates. Programs implementing mixed mechanisms should establish clear protocols for how community benefits are proposed, approved, procured, and verified, ensuring that individual participants retain agency while enabling collective solutions.

Recommendation 2: Credit community-level outcomes in carbon accounting. Current standards credit only individual landowner outcomes, making mixed mechanisms appear inefficient when evaluated on a per-recipient basis. If standards were adapted to recognize and verify community infrastructure benefits and documented spillover adoption—using monitoring approaches analogous to how grouped projects currently aggregate participants—mixed mechanisms would show substantially higher cost-effectiveness per dollar of climate finance deployed. This requires developing protocols for (i) measuring community reach (number of people benefiting from shared infrastructure), (ii) documenting spillover adoption among non-recipients, and (iii) attributing these outcomes to specific payment arrangements. Pilot crediting of community co-benefits, already emerging in some standards, should be systematized and scaled.

Recommendation 3: Target mixed mechanisms to settings above institutional thresholds. Mixed payment innovations cluster in districts exceeding approximately 38.9% organizational participation density in our setting, indicating that institutional prerequisites condition feasibility. Programs should assess local organizational capacity—including presence of established farmer groups, trusted leadership, and prior experience with collective resource management—before piloting mixed mechanisms. In low-capacity settings, cash-only designs with concurrent capacity-building may be more appropriate as initial interventions, with mixed mechanisms introduced once organizational density reaches sufficient levels. Phased rollouts with built-in learning, where a subset of communities receives encouragement to adopt mixed arrangements while others continue with cash-only, would allow programs to identify locally optimal cash–community shares while generating causal evidence.

7.2. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

Four limitations condition the interpretation and generalizability of our findings.

First, identification is associative, not causal. Our cross-sectional design compares farmers participating in different payment mechanisms under a common program architecture. While we employ district fixed effects, rich controls, propensity score matching, and sensitivity analyses to address selection on observables, we cannot rule out selection on unobservables. Farmers choosing mixed payments have higher baseline incomes and larger farms, and although regression adjustment suggests that the persistence of effects is conditional on covariates, unobserved characteristics—such as motivation, social capital, or forward-looking orientation—may drive both payment choice and land-use outcomes. Experimental or quasi-experimental designs that randomize payment types, or encouragement designs that shift the availability of mixed options while holding farmer characteristics constant, are needed to establish causality definitively.

Second, external validity depends on institutional context. Our findings emerge from a program with specific design features: long-term relationships between farmers and implementing organizations, GPS-verified monitoring, group-based structures, and established trust. Whether complementarity operates similarly in programs with different verification regimes, shorter time horizons, or weaker organizational foundations remains an empirical question. The organizational density threshold (≈38.9%) we identify is specific to TIST’s operational context; other programs may face higher or lower thresholds depending on local institutional capacity and the complexity of collective arrangements. Cross-program replication studies are essential to map the boundary conditions under which mixed mechanisms deliver super-additive effects.

Third, measurement constraints limit precision. Administrative effort indices capture procedural complexity rather than actual staff time or monetary costs. Farm sizes are self-reported and may contain measurement errors, particularly at the upper tail where we observe the largest mixed-payment effects. Trees per hectare is a flow outcome (current stock), rather than a dynamic measure, that tracks establishment, survival, and growth over time. Community reach is measured for a subset of arrangements (576 of 8432 farmers), and spillover effects are estimated using exposure to program presence rather than experimental variation. These measurement limitations introduce noise that may attenuate estimated effects, though they are unlikely to generate spurious positive associations.

Fourth, scope conditions apply. Our sample is concentrated in Kenya (74%), with smaller representation from Tanzania, Uganda, and India. Gender-disaggregated results reflect the specific constraints women face in these settings—norms around mobility, input access, and household financial control—which may differ in other contexts. The types of community benefits negotiated in our sample (schools, water points, shared inputs) represent the range of feasible options given local infrastructure gaps and procurement channels; different settings may generate different benefit portfolios with distinct effectiveness profiles. These results generalize most directly to carbon programs in smallholder settings with similar organizational structures, institutional capacity, and infrastructure needs.

7.3. Future Research Priorities

Three research directions would strengthen the evidence base for payment design. First, randomized or quasi-experimental studies that vary payment types while holding farmer characteristics constant are needed to establish causal effects and optimal cash–community shares. Second, longitudinal tracking of tree survival, growth trajectories, and sustained adoption over 5–10-year horizons would clarify whether complementarity translates into durable landscape change or reflects short-term responses to program presence. Third, comparative extension to European contexts and indicators would be beneficial. Although outside the scope of the present dataset (East Africa and South Asia), a structured comparison using EU-relevant sustainability indicators and institutional settings would test external validity and clarify conditions under which complementarity travels across regions. Engagement with the recommended European literature can guide indicator selection, program architecture contrasts, and policy relevance. Together, these directions would link internal and external validity: establishing causal mechanisms, quantifying dynamic benefits and full costs, and assessing transferability across institutional environments—including EU settings and generational renewal priorities—thereby advancing both science and policy design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and S.G.; methodology, P.L.; software, J.G.; validation, A.D., S.G., and L.Z.; formal analysis, A.D., J.G., and P.L.; investigation, A.D.; resources, J.G.; data curation, A.D. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., S.G. and P.L.; writing—review and editing, S.G., L.Z., and P.L.; visualization, A.D. and L.Z.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of third party usage limitations including ongoing research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Dr. James Gibson.

Acknowledgments

We thank the International Small Group and Tree Planting Program (TIST) for providing access to administrative records and survey data. We are grateful to the program participants and field enumerators who made this research possible. We acknowledge the valuable feedback from conference participants and anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TIST | International Small Group and Tree Planting Program |

| PES | Payments for Ecosystem Services |

| VER | Verified Emission Reduction |

| FE | Fixed Effects |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

References

- Haushofer, J.; Shapiro, J. Erratum to “The Short-term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers to the Poor: Experimental Evidence from Kenya”. Q. J. Econ. 2017, 132, 2057–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Sauer, J. The Cost Effectiveness of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 30, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Daidone, S.; Davis, B.; Handa, S.; Winters, P. The Household and Individual-Level Productive Impacts of Cash Transfer Programs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 1401–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing Payments for Environmental Services in Theory and Practice: An Overview of the Issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsenmeier, M.; Mohommad, A.; Schwarz, G. Global Carbon Pricing: Evidence from Border Adjustments. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 118, 102785. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, K.; Ndiaye, D. Supporting Climate Finance with Carbon Markets. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 151, 103628. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Labonne, J.; Chase, R.S. Do Community-Driven Development Projects Enhance Social Capital? Evidence from the Philippines. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Robinson, S.A. Agent-Based Modeling of Energy Technology Adoption: Empirical Integration of Social, Behavioral, Economic, and Environmental Factors. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 70, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebin, R.E.; Kedir, A.; Mussema, R. Sustainability and Collective Action in Smallholder Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, J.; Costanza, R. Payments for Ecosystem Services: From Local to Global. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, Y.; Wetterlind, J.; Jonsson, M. Effects of Agroforestry on Soil Fertility in East Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 301, 107034. [Google Scholar]

- Mashud, A.H.M.; Roy, D.; Daryanto, Y.; Chakrabortty, R.K. A Sustainable Inventory Model with Controllable Carbon Emissions in Green-Warehouse Farms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.; Roy, S.; Saha, S. Effectiveness of Payment Mechanisms in Ecosystem Services Programs. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 205, 107705. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, S.; De Laat, J.; Lambin, E.F.; Stanton, C.Y.; Audy, R.; Thomas, N.E. Cash for Carbon: A Randomized Trial of Payments for Ecosystem Services to Reduce Deforestation. Science 2017, 357, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, J.; Hultman, N.E.; Patwardhan, A.; Shindell, D. Integrating Social Co-benefits into Carbon Markets. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- Diiro, G.M.; Seymour, G.; Kassie, M.; Muricho, G.; Muriithi, B.W. Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture and Agricultural Productivity. World Dev. 2018, 105, 196–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ky, S.; Rugemintwari, C.; Sauviat, A. Credit Access and Agricultural Productivity. J. Afr. Econ. 2025, 34, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A.; Theis, S. Women in Agriculture: Four Myths. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisumbing, A.R.; Sproule, K.; Martinez, E.M.; Malapit, H. Do Tradeoffs Among Dimensions of Women’s Empowerment and Nutrition Outcomes Exist? Food Policy 2021, 104, 102142. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, E.; Brown, K.; Adger, W.N. The Equity and Legitimacy of Markets for Ecosystem Services. Dev. Change 2009, 38, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Ostrom, E. Applying the Social-Ecological System Framework to the Diagnosis of Urban Commons Management. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczan, D.; Swallow, B.M.; Adamowicz, W.L. Designing a Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) Program to Reduce Deforestation in Tanzania. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, K.P.; Smith, S.M.; Alston, L.J.; Andersson, E.P.; Licht, O.; Mello, R.; Giannini, F.; Fernández, L.C.; van Laerhoven, F. Wealth and the Distribution of Benefits from Tropical Forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4986–4991. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S.; Brouwer, R.; Engel, S.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Muradian, R.; Pascual, U.; Pinto, R. From Principles to Practice in Paying for Nature’s Services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J.; Bennett, G.; Carroll, N.; Goldstein, A.; Jenkins, M. The Global Status and Trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.P.; Cook, N.J.; Grillos, T.; Lopez, M.C.; Coslovsky, S.V.; Mwangi, E.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Experimental Evidence on Payments for Forest Commons Conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, U.; Meier, S.; Rey-Biel, P. When and Why Incentives (Don’t) Work to Modify Behavior. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2009, 15, 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zahid, S.; Khan, U.; Akbar, M.A. Impact of Organizational Learning on Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation and Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9152. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. The Effectiveness of Payments for Ecosystem Services in China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 63, 101547. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, S.; Harrison, G.W.; Lau, M.I.; Rutström, E.E. Elite Capture in Development Programs. J. Dev. Econ. 2022, 155, 102787. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural Dimensions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2010, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, A.; Demetriades, J.; Esplen, E. Gender and Climate Change: Mapping the Linkages—A Scoping Study on Knowledge and Gaps; BRIDGE, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2008; 27p. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C. Intrahousehold Bargaining and Resource Allocation in Developing Countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 2013, 28, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Osei, R.; Osei-Akoto, I.; Udry, C. Agricultural Decisions after Relaxing Credit and Risk Constraints. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 597–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, T.G. GMM Estimation with Cross Sectional Dependence. J. Econom. 1999, 92, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).