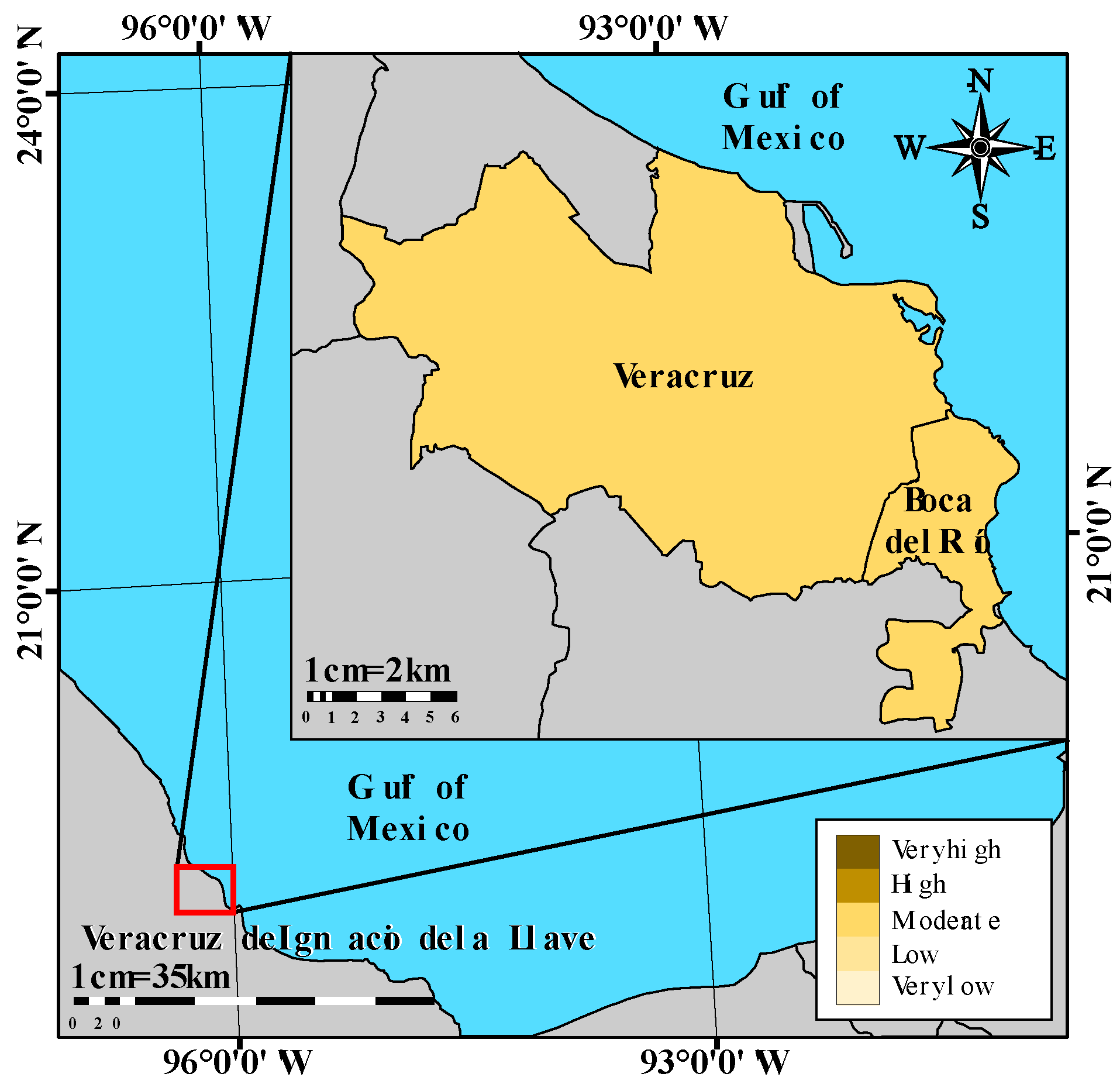

Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment: The Case of the Veracruz–Boca del Río Urban Conurbation, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

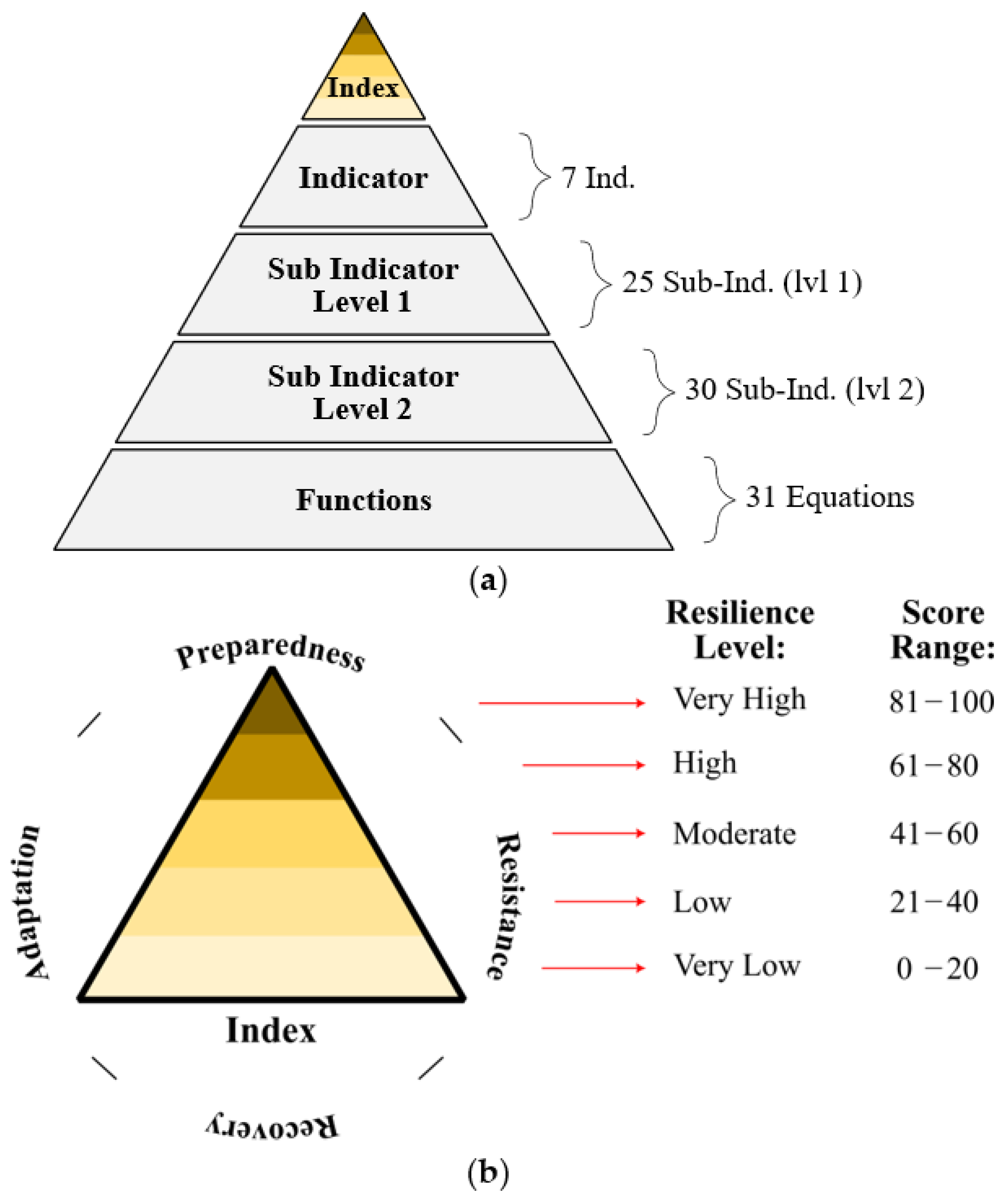

2. Methodology

- Infrastructure.

- Land use planning and ecological programs and building codes.

- Risk assessments.

- Disaster risk reduction plans.

- Budget assigned to emergency response.

- Institutions related to disaster risk reduction.

- Vital services.

- A.

- Predominant hazard.

- B.

- Recovery speed.

2.1. Technical Resilience Index (TRI)—Quantitative Analysis

- For variables without publicly available information, values were conservatively set to zero. This does not imply that the condition is literally absent. Rather, it reflects a methodological decision to exclude indicators for which reliable data could not be obtained.

- Seven variables required estimation, notably those related to essential services (such as access to potable water, electricity, and sewage systems). These were only available in aggregated form for the municipalities of Veracruz, Boca del Río, and Medellín de Bravo. To address this limitation, and to avoid reporting implausible values (e.g., zero coverage of potable water), the aggregated data were proportionally disaggregated according to the relative population size of each municipality. This approach ensured a reasonable approximation that preserved consistency and enabled the inclusion of these critical variables. In Appendix A, these estimated variables are marked with an asterisk (*).

2.2. Technical Profile of Resilience (TPR)—Qualitative Analysis

- Analysis of information on existing vulnerability, hazard, and risk in the city: Study of the main shortcomings and disadvantages of the urban area that increase exposure and susceptibility.

- Socioeconomic impacts of hydrometeorological events: An evaluation of the historical consequences of floods, hurricanes, and related phenomena on the city’s population, economy, and infrastructure.

- Predominant hazard analysis: Identification of the dominant hydrometeorological threats that shape local risk exposure.

- Water resource availability: Review of existing studies on the availability, use and distribution of water resources.

- Analysis of land use and ecological planning instruments, as well as of the regulation codes: Examination of the availability and currency of planning instruments, ecological frameworks and policies, and building codes that support urban development in the city.

- Statistics generation and updating: Production of new information from the literature review and resilience index, presented in graphs, maps, or tables.

- Proposal of structural and non-structural measures: Compilation of recommended strategies, both physical and institutional, aimed at strengthening resilience.

3. Results

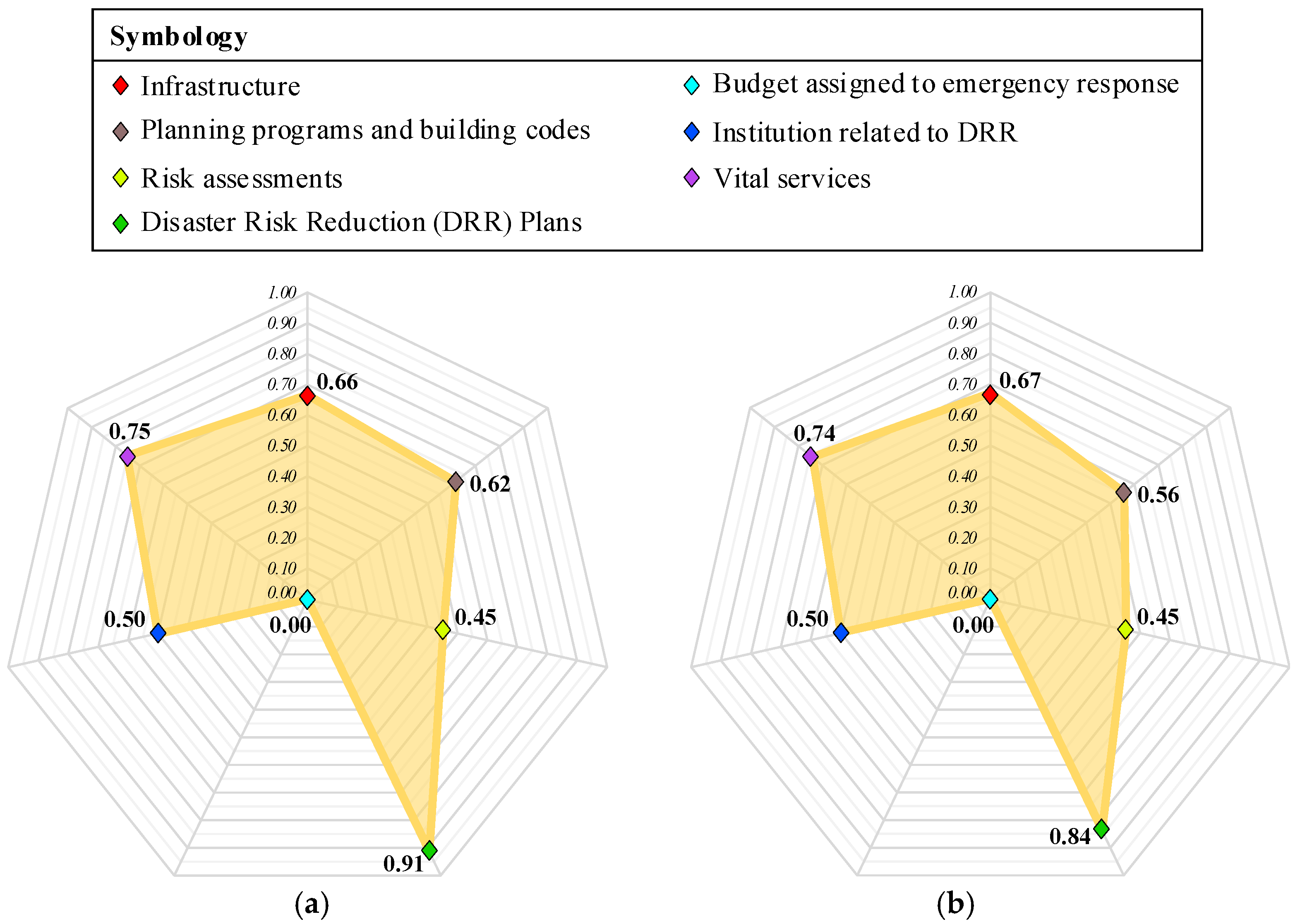

3.1. Quantitative Component (TRI) Results

3.1.1. Infrastructure Indicator

3.1.2. Indicator of Planning Programs and Building Codes

3.1.3. Indicator of Risk Assessments

3.1.4. Indicator of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Plans

3.1.5. Indicator of Budget Assigned to Emergency Response

3.1.6. Indicator of Institution Related to DRR

3.1.7. Indicator of Vital Services

3.1.8. Hydrometeorological Technical Resilience Index (TRI)

3.2. Qualitative Component (TPR) Results

- Updating the VBC Municipal Risk Atlas: The current atlases date to 2006 [29,30] and do not reflect updated information on hazards, vulnerabilities, and risks. Detailed multi-hazard maps are essential tools for planning spatially targeted interventions, as they allow authorities to reduce exposure and vulnerability while improving adaptive capacity in areas subject to multiple threats [93]. Updating this instrument would therefore strengthen territorial planning and emergency preparedness.

- Establishing a municipal historical damage database: Current records of damage to housing, infrastructure, and services remain incomplete and dispersed. While national-level databases have proven useful for identifying recurring vulnerabilities and guiding cost-effective preventive actions [94], developing this type of system at the municipal scale would provide greater spatial precision, enabling local authorities to prioritize interventions more effectively and strengthen long-term disaster management capacities.

- Developing relocation strategies for high-risk settlements: Populations living in flood-prone areas face recurrent threats to life and property. Developing clear, gradual relocation protocols aligns with established practices in managed retreat, which emphasize reducing human exposure and minimizing long-term economic losses [95].

- Developing a new sewage and drainage system for vulnerable neighborhoods. Frequent flooding in low-income areas is exacerbated by insufficient or deteriorated drainage. Investments in improved sewerage and stormwater management systems, such as permeable pavements and communal rainwater harvesting, have been proven to reduce exposure and improve adaptive capacity in coastal cities [96,97].

- Strengthening wind-resistant design standards: Given the exposure of coastal infrastructure to strong winds, it is essential to update design criteria for non-structural elements (e.g., light poles, signage), since the wind code currently in force for the VBC [98] focuses on civil structures and does not provide specific guidance for these components.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BM | Boca del Río Municipality |

| CENAPRED | Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres [National Center for Disaster Prevention in Mexico] |

| CRI | City Resilience Index |

| CONAGUA | Comisión Nacional del Agua [National Water Commission] |

| FIR | Ficha Informativa de los Humedales de Ramsar [Ramsar Wetlands Information Sheet] |

| DRR | Disaster Risk Reduction |

| FONDEN | Fondo de Desastres Naturales [Natural Disaster Fund] |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [National Institute of Statistics and Geography] |

| IMPLADE | Instituto Metropolitano de Planeación para el Desarrollo Sustentable [Metropolitan Institute for Sustainable Development Planning] |

| IMTA | Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua [Mexican Institute of Water Technology] |

| LDUOTVEVIDLL | Ley De Desarrollo Urbano, Ordenamiento Territorial Y Vivienda Para El Estado De Veracruz De Ignacio De La Llave [Urban Development, Territorial Planning and Housing Law for the State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave] |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| ORFIS | Órgano de Fiscalización Superior del Estado de Veracruz [Superior Audit Office of the State of Veracruz] |

| PEOTDUVDIL | Programa Estatal De Ordenamiento Territorial Y Desarrollo Urbano De Veracruz De Ignacio De La Llave [State Program for Territorial Planning and Urban Development of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave] |

| PIGOO | Programa de Indicadores de Gestión de Organismos Operadores [Management Indicators Program for Water Utility Agencies] |

| POTZMV | Programa de Ordenamiento Territorial de la Zona Metropolitana de Veracruz |

| [Territorial Planning Program for the Metropolitan Area of Veracruz] | |

| SEFIPLAN | Secretaría de Finanzas y Planeación [Secretariat of Finance and Planning] |

| SPCV | Secretaría de Protección Civil del Estado de Veracruz [Civil Protection Secretariat of the State of Veracruz] |

| TPR | Technical Profile of Resilience |

| TRI | Technical Resilience Index |

| UNDRR | United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction |

| VM | Veracruz Municipality |

| VBC | Zona Conurbada Veracruz—Boca del Río. [Veracruz—Boca del Río Conurbation] |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Infrastructure Indicator

| Indicator | 1. Infrastructure Weight = 30 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 1.1. Investment in new infrastructure * | 7.0 | |

| 1.2. Investment in maintenance * | 7.0 | ||

| 1.3. Supervision of the physical conditions of infrastructure * | 7.0 | ||

| 1.4. Critical infrastructure | 9.0 | ||

| 1.4.1. Hospitals * | 5.0 | ||

| 1.4.2. Schools * | 4.0 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Investment in infrastructure in the current period | $MXN | ||

| Growth rate in the current period | % | ||

| Investment in infrastructure in the previous period | $MXN | ||

| Growth rate in the previous period | % | ||

| Investment in maintenance in the current period | $MXN | ||

| Investment in maintenance in the previous period | $MXN | ||

| Number of supervisions made per year | supervisions | ||

| Connecting factor in America between the number of hospital beds and population | beds/10,000 inhab | ||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | inhab | ||

| Number of hospital beds in the city | beds | ||

| Number of basic education students in the city | students | ||

| Number of basic education schools in the city | schools | ||

| Connecting factor nationwide of student population and number of schools | students/schools | ||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19], (pp. 226–227). | |||

Appendix A.2. Indicator of Planning Programs and Building Codes

| Indicator | 2. Planning Programs and Building Codes Weight = 10 | Weight | Equation | ||

| Sub-indicators | 2.1. Land use | 2.50 | |||

| 2.1.1. Existence | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.1.2. Update * | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.2. Ecological | 2.50 | ||||

| 2.2.1. Existence | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.2.2. Update * | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.3. Regulation and building codes | 2.50 | ||||

| 2.3.1. Existence | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.3.2. Update * | 1.25 | ||||

| 2.4. Application of regulatory plans and codes | 2.50 | ||||

| Variables: | |||||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | years | ||||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | years | ||||

| Year the document was issued | years | ||||

| Number of works executed | works | ||||

| Number of works executed under supervision of a Chief Construction | works | ||||

| Assigned value: 1 | |||||

| Assigned value: 0 | |||||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19], (pp. 227–228). | |||||

Appendix A.3. Indicator of Risk Assessments

| Indicator | 3. Risk Assessments Weight = 10 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 3.1. Climate risk projections and trends | 2.0 | |

| 3.1.1. Existence | 1.0 | ||

| 3.1.2. Update * | 1.0 | ||

| 3.2. Hazard, exposure, and risk maps | 2.0 | ||

| 3.2.1. Existence | 1.0 | ||

| 3.2.2. Update * | 1.0 | ||

| 3.3. Insurance coverage statistics | 2.0 | ||

| 3.3.1. Existence | 1.0 | ||

| 3.3.2. Update * | 1.0 | ||

| 3.4. History of socioeconomic impacts | 2.0 | ||

| 3.4.1. Existence | 1.0 | ||

| 3.4.2. Update * | 1.0 | ||

| 3.5. Population in risk areas | 2.0 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | years | ||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | years | ||

| Year the document was issued | years | ||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | inhab | ||

| Number of inhabitants settled in risk areas within the city | inhab | ||

| Assigned value: 1 | |||

| Assigned value: 0 | |||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 229–230). | |||

Appendix A.4. Indicator of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Plans

| Indicator | 4. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Plans Weight = 10 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 4.1. Proactive | 3.50 | |

| 4.1.1. Existence | 1.75 | ||

| 4.1.2. Update * | 1.75 | ||

| 4.2. Reactive | 3.00 | ||

| 4.2.1. Existence | 1.50 | ||

| 4.2.2. Update * | 1.50 | ||

| 4.3. Post-disaster | 3.50 | ||

| 4.3.1. Existence | 1.75 | ||

| 4.3.2. Update * | 1.75 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | years | ||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | years | ||

| Year the document was issued | years | ||

| Assigned value: 1 | |||

| Assigned value: 0 | |||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 231–232). | |||

Appendix A.5. Indicator of Budget Assigned to Emergency Response

| Indicator | 5. Budget Assigned to Emergency Response Weight = 10 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 5.1. Budget assigned to emergencies * | 5.00 | |

| 5.2. Budget assigned to prevention programs * | 5.00 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Budget allocated for emergency response | $MXN | ||

| Budget allocated to the development of DRR plans and programs | $MXN | ||

| Budget of the city | $MXN | ||

| Historic percentage of investment on DRR | % | ||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 232–233). | |||

Appendix A.6. Indicator of Institution Related to DRR

| Indicator | 6. Institution Related to DRR Weight = 10 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 6.1. Qualified personnel (emergency response) * | 2.5 | |

| 6.2. Equipment * | 2.5 | ||

| 6.3. Units * | 2.5 | ||

| 6.4. Early-Warning system | 2.5 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Connecting factor between the population and trained personnel | inhab/personnel | ||

| Connecting factor between the population and number of units | inhab/ambulances | ||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | inhab | ||

| Number of trained personnel | personnel | ||

| Budget allocated for equipment acquisition | $MXN | ||

| Historic percentage of investment on DRR | % | ||

| Budget of the city | $MXN | ||

| Number of ambulances | ambulances | ||

| Assigned value: 1 | |||

| Assigned value: 0 | |||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 233–234). | |||

Appendix A.7. Indicator of Vital Services

| Indicator | 7. Critical Services Weight = 20 | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | 7.1. Drinking water | 7.0 | |

| 7.1.1. Service coverage | 1.0 | ||

| 7.1.2. 24 h service coverage | 1.0 | ||

| 7.1.3. PIGOO overall efficiency | 2.0 | ||

| 7.1.4. Water stress degree PRONACOSE * | 2.0 | ||

| 7.1.5. Supply | 1.0 | ||

| 7.2. Sanitation | 7.0 | ||

| 7.2.1. Sewerage service coverage | 3.0 | ||

| 7.2.2. Wastewater vs. Treated water | 2.0 | ||

| 7.2.3. Wastewater treatment plants | 2.0 | ||

| 7.3. Energy | 6.0 | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | inhab | ||

| Number of inhabitants with drinking water services | inhab | ||

| Number of inhabitants with 24 h drinking water services | inhab | ||

| Indicator of global efficiency of Water Utilities Management | % | ||

| Available guaranteed resources | hm3 | ||

| Environmental demand | hm3 | ||

| Demand for urban supply | hm3 | ||

| Other demands | hm3 | ||

| Supply per inhabitant per day in the city | l/inhab/day | ||

| Supply per inhabitant per day recommended by the World Health | l/inhab/day | ||

| Number of inhabitants with sewerage services | inhab | ||

| Amount of water used by the city | hm3 | ||

| Amount of water treated in the city | hm3 | ||

| Number of treatment plants in operation | plants | ||

| Number of treatment plants in the city | plants | ||

| Number of inhabitants with electricity service | inhab | ||

| * The sub-indicator has the condition: . Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 234–235). | |||

Appendix A.8. Hydrometeorological Event Indicator

| Indicator | A. Main Hazard Indicator | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | A.1 Droughts | -- | |

| A.2 Tropical cyclones | -- | ||

| A.3 Floods | -- | ||

| A.4 Frosts | -- | ||

| A.5 Frosts | -- | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Economic impact due to droughts in the city | $MXN | ||

| Economic impact due to tropical cyclones in the city | $MXN | ||

| Economic impact due to floods in the city | $MXN | ||

| Economic impact due to severe storms in the city | $MXN | ||

| Economic impact due to frost in the city | $MXN | ||

| Economic impact due to hydrometeorological events in the city | $MXN | ||

| Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 225–226). | |||

Appendix A.9. Indicator of Damage Assessment, Time and Speed of Recovery

| Indicator | B. Damage Assessment, Time and Speed of Recovery | Weight | Equation |

| Sub-indicators | B.1 Damaged infrastructure | -- | |

| B.1.1 Update of the number of the affected structures. | -- | ||

| B.1.2 Updated execution time | -- | ||

| B.2 Global assessment | -- | ||

| B.2.1 Cost of disaster | -- | ||

| B.2.2 Estimated recovery time | -- | ||

| B.3 Recovery speed | -- | ||

| Variables: | |||

| Original amount of work | $MXN | ||

| Year in which disaster occurred | years | ||

| Year of infrastructure construction | years | ||

| Time of execution of the infrastructure | months | ||

| Percentage of damage | % | ||

| Reconstruction time | months | ||

| Source: Bahena et al., 2021 [19] (pp. 236–237). | |||

Appendix A.10. Structure of the Indicators Comprising the Technical Index and Their Specific Contribution to the Core Dimensions of Hydrometeorological Resilience

| Indicator | Weight | Preparedness | Resistance | Recovery | Adaptation |

| A. Main hazard indicator | |||||

| A.1 Tropical cyclones | —— | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| A.2 Floods | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| A.3 Severe storms | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| A.4 Strong winds | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 1. Infrastructure | 30 | ||||

| 1.1 Investment in new infrastructure | 7.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1.2 Investment in maintenance | 7.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 1.3 Supervision of the physical conditions of infrastructure | 7.0 | ✓ | |||

| 1.4 Critical infrastructure | 9.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2. Planning programs and building codes | 10 | ||||

| 2.1 Land use | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2.2 Ecological | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2.3 Regulation and building codes | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2.4 Application of regulatory plans and codes | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3. Risk assessments | 10 | ||||

| 3.1 Climate risk projections and trends | 2.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3.2 Hazard, exposure, and risk maps | 2.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3.3 Insurance coverage statistics | 2.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3.4 History of socioeconomic impacts | 2.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3.5 Population in risk areas | 2.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) plans | 10 | ||||

| 4.1 Proactive | 3.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4.2 Reactive | 3.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4.3 Post-disaster | 3.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5. Budget assigned to emergency response | 10 | ||||

| 5.1 Budget assigned to emergencies | 5.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 5.2 Budget assigned to prevention programs | 5.0 | ✓ | |||

| 6. Institution related to DRR | 10 | ||||

| 6.1 Qualified personnel (emergency response) | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 6.2 Equipment | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6.3 Units | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6.4 Early-Warning system | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7. Critical services | 20 | ||||

| 7.1 Drinking water | 7.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7.2 Sanitation | 7.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7.3 Energy | 6.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| B. Damage assessment and time and speed of recovery | |||||

| B.1 Damaged infrastructure | —— | ✓ | |||

| B.2 Global assessment | ✓ | ||||

| B.3 Recovery speed | ✓ | ||||

| Note: The symbol “✓” indicates that the corresponding indicator contributes to the respective resilience dimension. Source: Adapted from (Bahena, 2021) [19] (pp. 214–218). | |||||

References

- Vieira Passos, M.; Barquet, K.; Kan, J.-C.; Destouni, G.; Kalantari, Z. Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment of Interconnected Critical Infrastructures. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2025, 10, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.R.; Renaud, F.G.; Anderson, C.C.; Wild, A.; Domeneghetti, A.; Polderman, A.; Votsis, A.; Pulvirenti, B.; Basu, B.; Thomson, C.; et al. A Review of Hydro-Meteorological Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk Assessment Frameworks and Indicators in the Context of Nature-Based Solutions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majlingova, A.; Kádár, T.S. From Risk to Resilience: Integrating Climate Adaptation and Disaster Reduction in the Pursuit of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzel, T.; Lüdeke, M.K.B.; Walther, C.; Kok, M.T.; Sietz, D.; Lucas, P.L. Typology of Coastal Urban Vulnerability under Rapid Urbanization. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodess, C.M. How Is the Frequency, Location and Severity of Extreme Events Likely to Change up to 2060? Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 27, S4–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, E.; Novelo Casanova, D.A.; Domínguez, C.; García Benítez, M.; Piña, V. A New Model to Analyze Urban Flood Risk. Case Study: Veracruz, Mexico. Nova Sci. 2022, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-González, C.; Moreno-Casasola, P.; Peralta Peláez, L.A.; Monroy, R.; Espejel, I. The Value of Coastal Wetland Flood Prevention Lost to Urbanization on the Coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico: An Analysis of Flood Damage by Hurricane Impacts. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 37, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, M.A.; Jiménez, M. Inundaciones, 1st ed.; CENAPRED: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; ISBN 9706288708. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cenapred/documentos/serie-de-fasciculos-inundaciones (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Kurhade, M.; Wankhade, R. An Overview on Decision Making Under Risk and Uncertainty. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, L.J. The Foundations of Statistics Dover Publications; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1954; ISBN 9780566003271. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, A. Statistical Decision Functions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 342–357. ISBN 978-1-4612-0919-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kmietowicz, Z.W.; Pearman, A.D. Decision Theory and Incomplete Knowledge; Gower Publishing Company Limited: Aldershot, UK, 1981; ISBN 0566003279. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspars-Wieloch, H. Modifications of the Hurwicz’s Decision Rule. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 22, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, B. A Critique of Some Classical Theories of Decisions Under Uncertainty. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 1996, 4, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ayan, B.; Abacıoğlu, S.; Basilio, M.P. A Comprehensive Review of the Novel Weighting Methods for Multi-Criteria Decision-Making. Information 2023, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-H. Integrating Subjective–Objective Weights Consideration and a Combined Compromise Solution Method for Handling Supplier Selection Issues. Systems 2023, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ji, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Environmental Vulnerability Assessment for Mainland China Based on Entropy Method. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Liu, Z.W.; Li, Q.; Shi, Y.L. A New Improved Entropy Method and Its Application in Power Quality Evaluation. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 706–708, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahena-Ayala, R.; Arreguín-Cortés, F.I.; Cervantes-Jaimes, C.E. Assessing Resilience of Cities to Hydrometeorological Hazards. Tecnol. Y Cienc. Del. Agua 2021, 12, 192–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.L.; Silva, R.; Chávez, V.; López-Portillo, J.; Salgado, K.; Marín-Coria, E.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Maximiliano-Cordova, C.; Landgrave, R.; de la Cruz, V. The Challenges of Climate Change and Human Impacts Faced by Mexican Coasts: A Comprehensive Evaluation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. How to Make Cities More Resilient A Handbook for Local Government Leaders; United Nations, UNISDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-92-1-101496-9. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/26462_handbookfinalonlineversion.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. On the Suitability of Assessment Tools for Guiding Communities towards Disaster Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR DesInventar: Disaster Information Management System. Available online: https://www.desinventar.net/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010. Veracruz. Veracruz de Ignacio de La Llave. 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/30/30193.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010. Boca del Río. Veracruz de Ignacio de La Llave. 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/30/30028.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020: Presentación de Resultados.Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave. 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- INEGI. Cuéntame de México: Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave. Available online: https://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/descubre/conoce_tu_estado/tarjeta.html?estado=30 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- INEGI. Principales Resultados. Censo de Población y vivienda. 2020. Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/702825198367.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- IMPLADE. Atlas de Riesgos Municipio Veracruz, Ver. 2006. Available online: https://rmgir.proyectomesoamerica.org/AtlasMunPDF/2010_anteriores/30193_VERACRUZ_2006.PDF (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- H. Ayuntamiento de Boca del Río. Atlas de Riesgos Naturales Para el Municipio de Boca del Río, Ver. 2006. Available online: http://atlasnacionalderiesgos.gob.mx/archivo/cob-atlas-municipales.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- ORFIS. Sistema de Consulta de Obras y Acciones Municipales de Veracruz. Available online: https://sistemas.orfis.gob.mx/simverp/home/municipios (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- H. Ayuntamiento de Veracruz Obras. Públicas y Desarrollo Urbano. Available online: https://gobiernoabierto.veracruzmunicipio.gob.mx/registrovisitasdomiciliarias/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- OECD. The World Bank. Panorama de La Salud: Latinoamérica y El Caribe 2020. OECD, 2020; ISBN 9789264973497. [CrossRef]

- Trading Economics Camas de Hospital por País—América. Available online: https://es.tradingeconomics.com/country-list/hospital-beds?continent=america (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Gobierno de Mexico DATA MEXICO: Veracruz. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/veracruz (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Gobierno de Mexico DATA MEXICO: Boca del Río. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/boca-del-rio (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- SEV. Anuario Estadístico. Información Estadística del Sistema Educativo Estatal. Available online: https://www.sev.gob.mx/v1/servicios/anuario-estadistico/consulta/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- SEP. Principales Cifras del Sistema Educativo Nacional 2024–2025. Mexico City, 2025. Available online: https://www.planeacion.sep.gob.mx/Doc/estadistica_e_indicadores/principales_cifras/principales_cifras_2024_2025_bolsillo.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Congreso del Estado de Veracruz. Ley de Desarrollo Urbano, Ordenamiento Territorial y Vivienda Para El Estado de Veracruz de Ignacio de La Llave. Congreso del Estado de Veracruz, 2021. Available online: https://www.legisver.gob.mx/Inicio.php?p=le (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- H. Ayuntamiento de Veracruz. Reglamento de Construcciones Públicas y Privadas del Municipio Libre de Veracruz. Xalapa, 2020. Available online: https://gobiernoabierto.veracruzmunicipio.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Gac2020-406-Viernes-09-TOMO-II-Ext-.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- H. Ayuntamiento de Boca del Río. Reglamento Para Construcciones Públicas y Privadas del Municipio Libre de Boca Del Río. Veracruz. 2022. Available online: https://sistemas4.cgever.gob.mx/Normatividad/archivos/pdfs/6/4222.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SPCV. Atlas de Riesgos del Estado de Veracruz 2023. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/proteccioncivil/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2024/10/Atlas-de-Riesgos-del-Estado-de-Veracruz_.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- CENAPRED. Información del Impacto Socioeconómico Provocado por Desastres en Mexico. Available online: https://historico.datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/informacion-del-impacto-socioeconomico-provocado-por-desastres-en-mexco (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- SPCV. Índice de Vulnerabilidad Social. Veracruz, Ver. 2024. Available online: http://www.atlasnacionalderiesgos.gob.mx/InformacionBasicaMunicipal/Veracruz/30193.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- SPCV. Índice de Vulnerabilidad Social. Boca del Río, Ver. 2024. Available online: http://www.atlasnacionalderiesgos.gob.mx/InformacionBasicaMunicipal/Veracruz/30028.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- SEFIPLAN. Presupuesto de Egresos 2025. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/finanzas/transparencia/transparencia-proactiva/programacion-y-presupuesto/presupuesto/presupuesto-de-egresos-2025/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- El Arsenal En Veracruz, Alrededor de 3 Mil Elementos Son Desplegados en Operativo Semana Santa. El Arsenal. Diario Digital, 15 April 2025. Available online: https://www.elarsenal.net/?p=1206684 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- H. Ayuntamiento de Veracruz. Respuesta a Oficio PM/UT/1016/19. Veracruz, 15 October 2019. Available online: https://gobiernoabierto.veracruzmunicipio.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Respuesta-PNT-05362619.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Secretaría de Economía DATA México: Medellín de Bravo. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/medellin-de-bravo (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Hansen, P.; Rodríguez, J. Indicadores de Gestión Prioritarios en Organismos Operadores. Informe Final HC1915.1. 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.imta.mx/handle/20.500.12013/2221 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- CONANP. ¿Sabes Cuántas Agua Consumes? Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conanp/es/articulos/sabes-cuanta-agua-consumes (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- CONAGUA. Inventario Nacional de Plantas Municipales de Potabilización y de Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales en Operación. 2015. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/197610/Inventario_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SEMARNAT. Compendio de Estadísticas Ambientales 2021: Cobertura de Población Con Servicio de Energía Eléctrica (Porcentaje). Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/compendio_2021/dgeiawf.semarnat.gob.mx_8080/ibi_apps/WFServletc64c.html (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Méndez, K.; Franco, E.; Nolasco, J.; Baeza, C.; Cordero, D. Subdirección de Riesgos Sísmicos. Impacto Socioeconómico de Los Principales Desastres Ocurridos en la República Mexicana en 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.cenapred.unam.mx/PublicacionesWebGobMX/buscar_buscaSubcategoria (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Méndez, K. 20 Años del Análisis del Impacto Socio-Económico de los Desastres. 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/875600/Tema_4_AIED_cf.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- UNDRR Perfil de País: México. Available online: https://www.desinventar.net/DesInventar/profiletab.jsp?countrycode=mex&continue=y (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Medina, V. Fuerte Lluvia Causa Severas Inundaciones en Veracruz y Boca del Río; ¿seguirá Lloviendo? N+, 31 May 2025. Available online: https://www.nmas.com.mx/racruz/lluvia-causa-inundaciones-veracruz-y-boca-del-rio-hoy-31-de-mayo-seguira-lloviendo/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ruíz, I. Lluvia Por Frente Frío 20 en Veracruz Inunda Calles y Causa Cortes de Energía Eléctrica. Diario de Xalapa, 3 January 2025. Available online: https://oem.com.mx/diariodexalapa/local/lluvia-por-frente-frio-20-en-veracruz-inunda-calles-y-causa-cortes-de-energia-electrica-20966652 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bermúdez, M. Veracruz Bajo El Agua: Fuerte Lluvia Causa Inundaciones en la Ciudad. La Silla Rota Veracruz, 3 January 2025. Available online: https://lasillarota.com/veracruz/local/2025/1/3/veracruz-bajo-el-agua-fuerte-lluvia-causa-inundaciones-en-la-ciudad-516895.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Toriz, V. Lluvias Dejan Calles Inundadas y Suspensión de Clases en Veracruz y Boca del Río. La Silla Rota Veracruz, 21 October 2024. Available online: https://lasillarota.com/veracruz/local/2024/10/21/lluvias-dejan-calles-inundadas-suspension-de-clases-en-veracruz-boca-del-rio-506579.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Salomón, A. Inundaciones y Socavón Dejan Lluvias en Puerto de Veracruz. QUADRATIN Veracruz, 21 October 2024. Available online: https://veracruz.quadratin.com.mx/inundaciones-y-socavon-dejan-lluvias-en-puerto-de-veracruz/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Navarrete, C. Revelan Afectaciones por las Lluvias en la Zona de Veracruz-Boca del Río. e-consulta Veracruz, 22 October 2024. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2024-10-22/municipios/revelan-afectaciones-por-las-lluvias-en-la-zona-de-veracruz-boca-del-rio (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bermúdez, M. Autos Varados e Inundaciones: Afectaciones por la Tormenta en Veracruz. La Silla Rota Veracruz, 26 September 2024. Available online: https://lasillarota.com/veracruz/local/2024/9/26/autos-varados-inundaciones-afectaciones-por-la-tormenta-en-veracruz-503247.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SPCV. PC Informa Atenciones por Lluvias en Veracruz-Boca del Río. Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz. Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz, 10 July 2024. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/2024/07/10/pc-informa-atenciones-por-lluvias-en-veracruz-boca-del-rio/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Flores, D. Onda Tropical Causa Inundaciones y Socavones en la Zona Conurbada Veracruz–Boca del Río: PC. Diario de Xalapa, 2024. Available online: https://oem.com.mx/diariodexalapa/local/onda-tropical-causa-inundaciones-y-socavones-en-la-zona-conurbada-veracruz-boca-del-rio-pc-video-13443293 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- García, I. Lluvias Inundan Zona Conurbada Veracruz–Boca del Río. E-Veracruz. e-consulta Veracruz, 9 July 2024. Available online: https://da21w.e-veracruz.mx/nota/2024-07-09/municipios/lluvias-inundan-zona-conurbada-veracruz-boca-del-rio (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Coto, J. Calles Inundadas y Vehículos Varados por Intensa Lluvia en Veracruz–Boca del Río. XEU Noticias, 5 August 2023. Available online: https://xeu.mx/veracruz/1283748/calles-inundadas-y-vehiculos-varados-por-intensa-lluvia-en-veracruz-boca-del-rio-videos (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Arellano, A. Inundaciones y Caos Vial Ocasiona Lluvia en Veracruz–Boca del Río. XEU Noticias, 5 June 2025. Available online: https://xeu.mx/veracruz/1274730/inundaciones-y-caos-vial-ocasiona-lluvia-en-veracruzboca-del-rio (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Mont, L. Calles Inundadas Fue la Principal Afectación de las Lluvias en Veracruz Puerto y Boca Del Río. masnoticias, 15 September 2022. Available online: https://www.masnoticias.mx/calles-inundadas-fue-la-principal-afectacion-de-las-lluvias-en-veracruz-puerto-y-boca-del-rio/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bermúdez, M. Activan Plan DN-III-E en Colonias de Veracruz Puerto por Inundaciones. e-consulta-Veracruz, 3 September 2022. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2022-09-03/veracruz/activan-plan-dn-iii-e-en-colonias-de-veracruz-puerto-por-inundaciones (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- La Clave Redacción Se Inunda Zona Conurbada del Puerto de Veracruz por Fuertes Lluvias. Activan Plan DN-III. La Clave, 4 September 2022. Available online: https://laclaveonline.com/2022/09/04/activan-plan-dn-iii-por-inundaciones-en-la-conurbacion-veracruz-boca-del-rio/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Guevara, M. Calles Inundadas Dejó Lluvia Registrada en Veracruz. masnoticias, 28 July 2022. Available online: https://www.masnoticias.mx/calles-inundadas-dejo-lluvia-registrada-en-veracruz/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Cortés, Á. “Nos Inundamos Cada Año y Estamos Olvidados”, Vecinos En Veracruz. e-consulta-Veracruz, 22 November 2021. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2021-11-22/veracruz/nos-inundamos-cada-ano-y-estamos-olvidados-vecinos-en-veracruz (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bermúdez, M. Tras Lluvia, Veracruz y Boca del Río Amanecen Con Calles Inundadas. e-consulta-Veracruz, 22 October 2021. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2021-10-22/veracruz/tras-lluvia-veracruz-y-boca-del-rio-amanecen-con-calles-inundadas (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bermúdez, M. Amanece Veracruz Puerto Bajo El Agua; Intensas Lluvias Inundaron Calles. e-consulta-Veracruz, 31 May 2021. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2021-05-31/veracruz/amanece-veracruz-puerto-bajo-el-agua-intensas-lluvias-inundaron-calles (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Flores, D. Lluvias En Veracruz Continuarán; Deja Afectaciones por Inundaciones: PC. El Sol de Córdoba, 11 June 2020. Available online: https://oem.com.mx/elsoldecordoba/local/lluvias-en-veracruz-continuaran-deja-afectaciones-por-inundaciones-pc-temporada-de-lluvias-cristobal-huracan-damnificados-18959581 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ávalos, E. Inundaciones en Colonias de Veracruz Alcanzaron Hasta Medio Metro: PC. XEU Noticias, 28 July 2019. Available online: https://xeu.mx/veracruz/1070723/inundaciones-en-colonias-de-veracruz-alcanzaron-hasta-medio-metro-pc (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- López-Dóriga Digital Lluvia Provoca Inundaciones en El Puerto de Veracruz. López-Dóriga Digital, 13 September 2019. Available online: https://lopezdoriga.com/nacional/lluvia-provoca-inundaciones-en-el-puerto-de-veracruz/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Gómez, E. Daños en 20 Colonias por Lluvias en Veracruz. La Jornada, 4 August 2018. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2018/08/04/estados/029n1est (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Atl, A. Tres Horas de Lluvia Intensa Dejan Inundaciones y Daños en Veracruz Puerto. e-consulta-Veracruz, 3 August 2018. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2018-08-03/veracruz/tres-horas-de-lluvia-intensa-dejan-inundaciones-y-danos-en-veracruz-puerto (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Periodistasdigitales Por Exceso de Basura, Lluvia Inundó Varias Zonas En El Puerto de Veracruz. PlumasLibres, 26 April 2018. Available online: https://plumaslibres.com.mx/2018/04/26/exceso-basura-lluvia-inundo-varias-zonas-puerto-veracruz/index.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Flores, D. Veracruz Bajo El Agua: Lluvia Causa Graves Inundaciones. Agua.org.mx, 31 May 2017. Available online: https://agua.org.mx/veracruz-bajo-agua-lluvia-causa-graves-inundaciones/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Crónica Veracruz Galería y Videos de Las Inundaciones En Veracruz. Crónica Veracruz, 23 August 2016. Available online: https://cronicaveracruz.com/informacion/noticias/96098/galer-a-y-videos-de-las-inundaciones-en-veracruz.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- E-consulta-Veracruz Sin Afectaciones por la Lluvia de Esta Madrugada en Veracruz Puerto. e-consulta-Veracruz, 16 August 2016. Available online: https://e-veracruz.mx/nota/2016-08-16/municipios/sin-afectaciones-por-la-lluvia-de-esta-madrugada-en-veracruz-puerto (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Hernández, A.; Bravo, C.; Díaz, J. Reseña Del Huracán “Karl” del Océano Atlántico, 2010. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/ciclones-tropicales/informacion-historica (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- CONAGUA. Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en El Acuífero Costera de Veracruz (3006), Estado de Veracruz. Mexico City, 2024. Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/sections/Edos/veracruz/veracruz.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- CONAGUA. Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en El Acuífero Cotaxtla (3008), Estado de Veracruz; Mexico City, 2024. Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/Edos_Acuiferos_18/veracruz/DR_3008.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SEDESOL. Programa Estatal de Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano de Veracruz y de Ignacio de la Llave (PEOTDUVDIL); Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz: Xalapa-Enríquez, 2021. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/desarrollosocial/programa-estatal-de-ordenamiento-territorial-y-desarrollo-urbano-de-veracruz-y-de-ignacio-de-la-llave/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SEDATU. Programa de Ordenamiento Urbano de la Zona Conurbada Veracruz-Boca del Río-Medellín-Alvarado (POUZCVBRMA). 2008. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/desarrollosocial/direcciones/direccion-general-de-desarrollo-urbano-y-ordenamiento-territorial/programas-de-ordenamiento/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- SEDATU. Programa de Ordenamiento Territorial de La Zona Metropolitana de Veracruz (POTZMV). 2021. Available online: https://www.veracruz.gob.mx/desarrollosocial/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2022/02/ZMV-Presentaci%C3%B3n-Resumen-23.12.21.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- FAO. Plataforma de Territorios y Paisajes Inclusivos y Sostenibles. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/territorios-inteligentes/componentes/ordenamiento-territorial/contexto-general/es/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- SEMARNAT. Ordenamiento Ecológico Del Territorio. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/acciones-y-programas/ordenamiento-ecologico-del-territorio (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Amarnath, G.; Amarasinghe, U.A.; Alahacoon, N. Disaster Risk Mapping: A Desk Review of Global Best Practices and Evidence for South Asia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Díaz, F.; Marín Ferrer, M. Loss Database Architecture for Disaster Risk Management; Luxemburg. 2018. Available online: https://civil-protection-knowledge-network.europa.eu/system/files/2024-04/loss-database-architecture-jrc110489%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Siders, A.R. Managed Retreat in the United States. One Earth 2019, 1, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Kumar, A. Evaluation of Stormwater Management Approaches and Challenges in Urban Flood Control. Urban. Clim. 2023, 51, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Ho, M.-C.; Chiou, Y.-S.; Huang, L.-L. Assessing the Performance of Permeable Pavement in Mitigating Flooding in Urban Areas. Water 2023, 15, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFE; INEEL. Manual de Diseño de Obras Civiles, Sección C: Estructuras, Tema 1: Criterios Generales de Análisis y Diseño, Capítulo C.1.4 Diseño por Viento; CFE: Mexico City, Mexico. 2020. Available online: https://civil.ineel.mx/SistViento/es/viento.php (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Mulia, F.A.; Handayani, W. Assessment and Comparison of Community Resilience to Floods and Tsunamis in Padang, Indonesia. J. Integr. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 14, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P.; Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Peña y Lillo, O.; Ariccio, S.; Ceballo, M. Resilient Planning Pathways to Community Resilience to Tsunami in Chile. Habitat. Int. 2024, 152, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukounis, C.N.; Tsoukala, V.K.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. An Index-Based Method to Assess the Resilience of Urban Areas to Coastal Flooding: The Case of Attica, Greece. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Ortiz, J. Gestión Integral de Diseño. Vulnerabilidad Social y Manejo de Riesgos Hidrometeorológicos En Veracruz: Comprehensive Design Management. Social Vulnerability and Hydrometeorological Risk Management in Veracruz. RDEIADyC 2024, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Geneva. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- ISO 37123:2019; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for Resilient Cities. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70428.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

| Indicator | 1. Infrastructure Weight = 30 | Weight | Estimation | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | ||

| Sub-indicators | 1.1. Investment in new infrastructure | 7.0 | 7.0 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 4.86 | 4.16 | |

| 1.2. Investment in maintenance | 7.0 | 7.0 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 7.00 | ||

| 1.3. Supervision of the physical conditions of infrastructure | 7.0 | 7.0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 1.4. Critical infrastructure | 9.0 | 9.0 | ||||||

| 1.4.1. Hospitals | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 1.4.2. Schools | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 3.00 | 3.86 | ||

| Total | 19.94 | 20.03 | ||||||

| Variables | Values | |||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | ||||||

| Investment in infrastructure in the current period | 298,997,403.58 [31] | 74,385,722.77 [31] | $MXN | |||||

| Growth rate in the current period | 0 | 0 | % | |||||

| Investment in infrastructure in the previous period | 430,692,590.10 [31] | 125,108,916.07 [31] | $MXN | |||||

| Growth rate in the previous period | 0 | 0 | % | |||||

| Investment in maintenance in the current period | 580,000.00 [31] | 56,329,022.58 [31] | $MXN | |||||

| Investment in maintenance in the previous period | 52,674,539.13 [31] | 41,412,684.15 [31] | $MXN | |||||

| Number of supervisions made per year | 1172 [32] | 0 | supervisions | |||||

| Connecting factor in America between the number of hospital beds and population | 24.47 [33,34] | 24.47 [33,34] | beds/10,000 inhab | |||||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | 607,209 [35] | 144,550 [36] | inhab | |||||

| Number of hospital beds in the city | 1724 [35] | 534 [36] | beds | |||||

| Number of basic education students in the city | 86,522 [37] | 19,706 [37] | students | |||||

| Number of basic education schools in the city | 645 [37] | 189 [37] | schools | |||||

| Connecting factor nationwide of student population and number of schools | 101 [38] | 101 [38] | students/schools | |||||

| Indicator | 2. Planning Programs and Building Codes Weight = 10 | Weight | Estimation | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | ||

| Sub-indicators | 2.1. Land use | 2.50 | 2.50 | |||||

| 2.1.1. Existence | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | ||

| 2.1.2. Update | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | ||

| 2.2. Ecological | 2.50 | 2.50 | ||||||

| 2.2.1. Existence | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2.2.2. Update | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2.3. Regulation and building codes | 2.50 | 2.50 | ||||||

| 2.3.1. Existence | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | ||

| 2.3.2. Update | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | ||

| 2.4. Application of regulatory plans and codes | 2.50 | 2.50 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 1.17 | 0.57 | ||

| Total | 6.17 | 5.57 | ||||||

| Variables | Values | |||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | ||||||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | 5 | 5 | years | |||||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | 2025 | 2025 | years | |||||

| Urban Development, Territorial Planning, and Housing Law of the State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave | 2021 [39] | 2021 [39] | years | |||||

| Publication Year of the Ecological Planning Instrument | 0 | 0 | years | |||||

| Regulations Governing Public and Private Construction in the Municipality of Veracruz | 2020 [40] | 2022 [41] | years | |||||

| Number of works executed | 30 [31] | 22 [31] | works | |||||

| Number of works executed under supervision of a Chief Construction | 14 [31] | 5 [31] | works | |||||

| Indicator | 3. Risk Assessments Weight = 10 | Weight | Estimation | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | ||

| Sub-indicators | 3.1. Climate risk projections and trends | 2.0 | 2.0 | |||||

| 3.1.1. Existence | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3.1.2. Update | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | ||

| 3.2. Hazard, exposure, and risk maps | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||||||

| 3.2.1. Existence | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3.2.2. Update | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | ||

| 3.3. Insurance coverage statistics | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||||||

| 3.3.1. Existence | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 3.3.2. Update | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 3.4. History of socioeconomic impacts | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||||||

| 3.4.1. Existence | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3.4.2. Update | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3.5. Population in risk areas | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Total | 4.52 | 4.52 | ||||||

| Variables | Values | |||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | ||||||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | 5 | 5 | years | |||||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | 2025 | 2025 | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2006 [29] | 2006 [30] | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2006 [29] | 2006 [30] | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 0 | 0 | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2024 [43] | 2024 [43] | years | |||||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | 751,759 [26] | 144,550 [26] | inhab | |||||

| Number of inhabitants settled in risk areas within the city | 0 | 0 | inhab | |||||

| Indicator | 4. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Plans Weight = 10 | Weight | Estimation | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | ||

| Sub-indicators | 4.1. Proactive | 3.50 | 3.50 | |||||

| 4.1.1. Existence | 1.75 | 1.75 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.88 | ||

| 4.1.2. Update | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.75 | 1.75 | ||

| 4.2. Reactive | 3.00 | 3.00 | ||||||

| 4.2.1. Existence | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.75 | ||

| 4.2.2. Update | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 1.50 | ||

| 4.3. Post-disaster | 3.50 | 3.50 | ||||||

| 4.3.1. Existence | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.75 | 1.75 | ||

| 4.3.2. Update | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.75 | 1.75 | ||

| Total | 9.13 | 8.38 | ||||||

| Variables | Values | |||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | ||||||

| Maximum number of years for considering a document to be updated | 5 | 5 | years | |||||

| Year in which the assessment is performed | 2025 | 2025 | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2024 [44] | 2024 [45] | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2024 [44] | 2024 [45] | years | |||||

| Year the document was issued | 2024 [44] | 2024 [45] | years | |||||

| Indicator | 5. Budget Assigned to Emergency Response Weight = 10 | Weight | Estimation | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | |

| Sub-indicators | 5.1. Budget assigned to emergencies | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5.2. Budget assigned to prevention programs | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| Variables | Values | ||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | |||||

| Budget allocated for emergency response | 0 | 0 | $MXN | ||||

| Budget allocated to the development of DRR plans and programs | 0 | 0 | $MXN | ||||

| Budget of the city | 175,245,285,470.00 [46] | 554,370,785.00 [46] | $MXN | ||||

| Historic percentage of investment on DRR | 1 [46] | 1 [46] | % | ||||

| Indicator | 6. Institution Related to DRR Weight = 10 | Weight | Estimation | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | |

| Sub-indicators | 6.1. Qualified personnel (emergency response) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 6.2. Equipment | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 6.3. Units | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| 6.4. Early-Warning system | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 5.00 | 5.00 | |||||

| Variables | Values | ||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | |||||

| Connecting factor between the population and trained personnel | 257.41 [35,47] | 245.41 [36,47] | inhab/personnel | ||||

| Connecting factor between the population and number of units | 5782.94 [35,47] | 5559.61 [36,47] | inhab/ambulances | ||||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | 607,209 [35] | 144,550 [36] | inhab | ||||

| Number of trained personnel | 2359 [47] | 589 [47] | personnel | ||||

| Budget allocated for equipment acquisition | 0 | 0 | $MXN | ||||

| Historic percentage of investment on DRR | 1 [46] | 1 [46] | % | ||||

| Budget of the city | 175,245,285,470.00 [46] | 554,370,785.00 [46] | $MXN | ||||

| Number of ambulances | 105 [47] | 26 [47] | ambulances | ||||

| Indicator | 7. Critical Services Weight = 20 | Weight | Estimation | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM | |

| Sub-indicators | 7.1. Drinking water | 7.0 | 7.0 | ||||

| 7.1.1. Service coverage | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| 7.1.2. 24 h service coverage | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.63 | |

| 7.1.3. PIGOO overall efficiency | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.89 | |

| 7.1.4. Water stress degree PRONACOSE | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 7.1.5. Supply | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.92 | |

| 7.2. Sanitation | 7.0 | 7.0 | |||||

| 7.2.1. Sewerage service coverage | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 1.78 | 1.45 | |

| 7.2.2. Wastewater vs. Treated water | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| 7.2.3. Wastewater treatment plants | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| 7.3. Energy | 6.0 | 6.0 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 5.93 | 5.93 | |

| Total | 15.06 | 14.81 | |||||

| Variables | Values | ||||||

| VM | BM | Unit | |||||

| Number of inhabitants in the city | 607,209 [35] | 144,550 [36] | inhab | ||||

| Number of inhabitants with drinking water services | 604,282 * [35,48,49] | 144,066 * [36,48,49] | inhab | ||||

| Number of inhabitants with 24 h drinking water services | 470,851 * [35,48,49] | 91,332 * [36,48,49] | inhab | ||||

| Indicator of global efficiency of Water Utilities Management | 44.80 [50] | 44.80 [50] | % | ||||

| Available guaranteed resources | 78.69 * [35,48] | 19.67 * [36,48] | hm3 | ||||

| Environmental demand | 0 | 0 | hm3 | ||||

| Demand for urban supply | 0 | 0 | hm3 | ||||

| Other demands | 0 | 0 | hm3 | ||||

| Supply per inhabitant per day in the city | 300 [35,48] | 72 [36,48] | l/inhab/day | ||||

| Supply per inhabitant per day recommended by the World Health | 100 [51] | 100 [51] | l/inhab/day | ||||

| Number of inhabitants with sewerage services | 361,795 * [35,48] | 70,178 * [36,48] | inhab | ||||

| Amount of water used by the city | 46.44 * [35,48] | 11.61 * [36,48] | hm3 | ||||

| Amount of water treated in the city | 27.78 * [35,48] | 6.95 * [36,48] | hm3 | ||||

| Number of treatment plants in operation | 25 [52] | 2 [52] | plants | ||||

| Number of treatment plants in the city | 25 [52] | 2 [52] | plants | ||||

| Number of inhabitants with electricity service | 600,468 * [35,53] | 142,945 * [36,53] | inhab | ||||

| Indicator | Weight | Score | Score vs. Weight | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBC | VM | BM | VM | BM | VM | BM |

| 1. Infrastructure | 30 | 30 | 19.94 | 20.03 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| 2. Planning programs and building codes | 10 | 10 | 6.17 | 5.57 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

| 3. Risk assessments | 10 | 10 | 4.53 | 4.53 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| 4. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) plans | 10 | 10 | 9.13 | 8.38 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| 5. Budget assigned to emergency response | 10 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 6. Institution related to DRR | 10 | 10 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| 7. Vital services | 20 | 20 | 15.06 | 14.81 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 59.83 | 58.32 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Márquez-Domínguez, S.; Barradas-Hernández, J.E.; Carpio-Santamaria, F.A.; Vargas-Colorado, A.; Delgado-Reyes, G.; Piña-Flores, J.; Aguilar-Meléndez, A.; Gómez-Velasco, B.d.J.; Ramírez-González, I.; Mota-López, B.J.; et al. Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment: The Case of the Veracruz–Boca del Río Urban Conurbation, Mexico. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229986

Márquez-Domínguez S, Barradas-Hernández JE, Carpio-Santamaria FA, Vargas-Colorado A, Delgado-Reyes G, Piña-Flores J, Aguilar-Meléndez A, Gómez-Velasco BdJ, Ramírez-González I, Mota-López BJ, et al. Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment: The Case of the Veracruz–Boca del Río Urban Conurbation, Mexico. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229986

Chicago/Turabian StyleMárquez-Domínguez, Sergio, José E. Barradas-Hernández, Franco A. Carpio-Santamaria, Alejandro Vargas-Colorado, Gustavo Delgado-Reyes, José Piña-Flores, Armando Aguilar-Meléndez, Bryan de Jesús Gómez-Velasco, Irving Ramírez-González, Brandon Josafat Mota-López, and et al. 2025. "Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment: The Case of the Veracruz–Boca del Río Urban Conurbation, Mexico" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229986

APA StyleMárquez-Domínguez, S., Barradas-Hernández, J. E., Carpio-Santamaria, F. A., Vargas-Colorado, A., Delgado-Reyes, G., Piña-Flores, J., Aguilar-Meléndez, A., Gómez-Velasco, B. d. J., Ramírez-González, I., Mota-López, B. J., Uscanga-Villafañez, D., Osorio-González, J. d. J., & Martínez-Cosío, M. d. l. Á. (2025). Hydrometeorological Resilience Assessment: The Case of the Veracruz–Boca del Río Urban Conurbation, Mexico. Sustainability, 17(22), 9986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229986