Effects of Customized Generative AI on Student Engagement and Emotions in Visual Communication Design Education: Implications for Sustainable Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

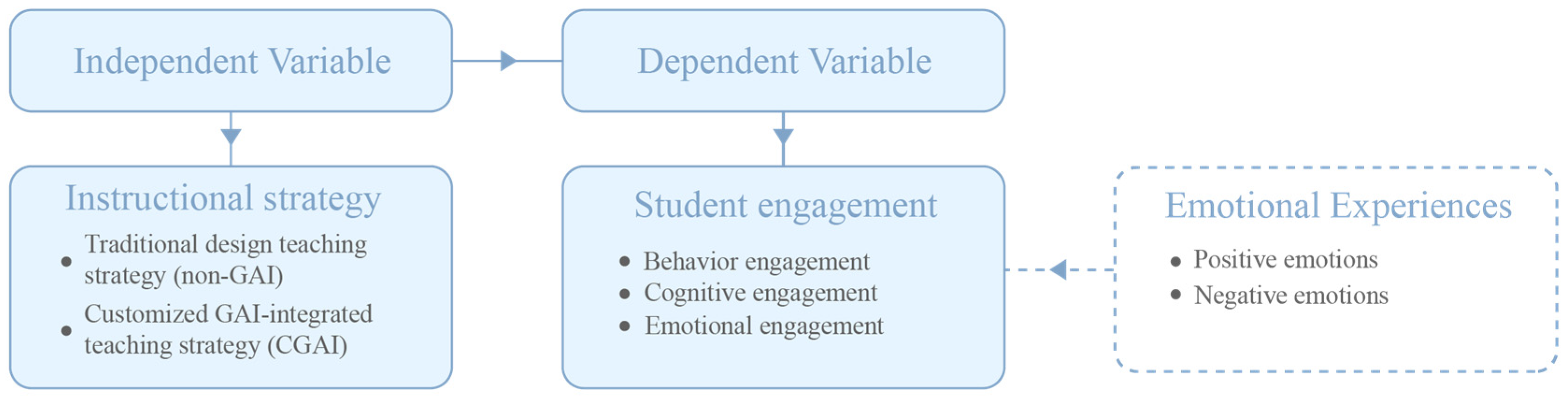

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Artificial Intelligence and Student Engagement

2.3. GAI in Visual Communication Design Education

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Student Engagement Scale

3.2.2. Semi-Structured Interview

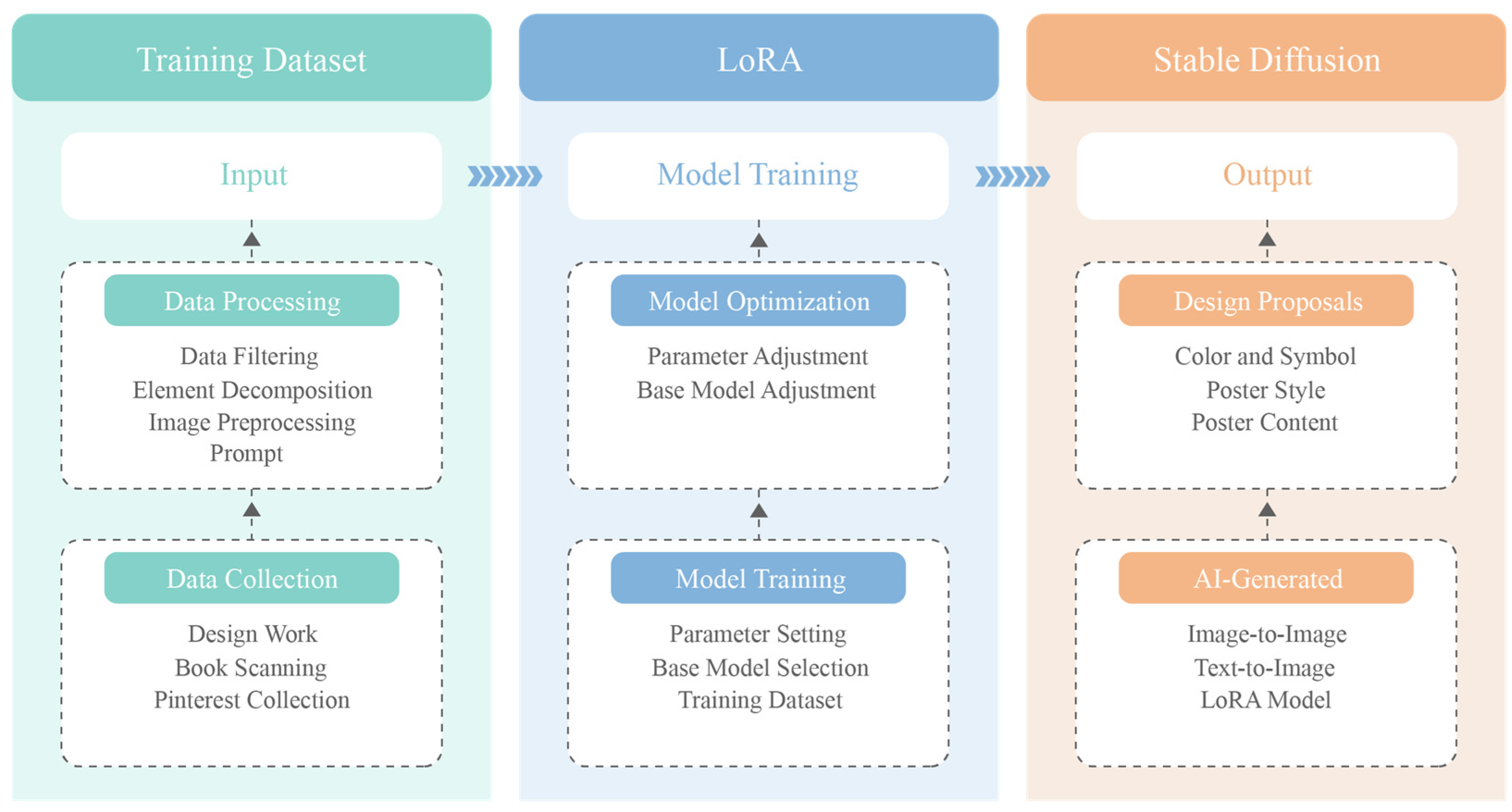

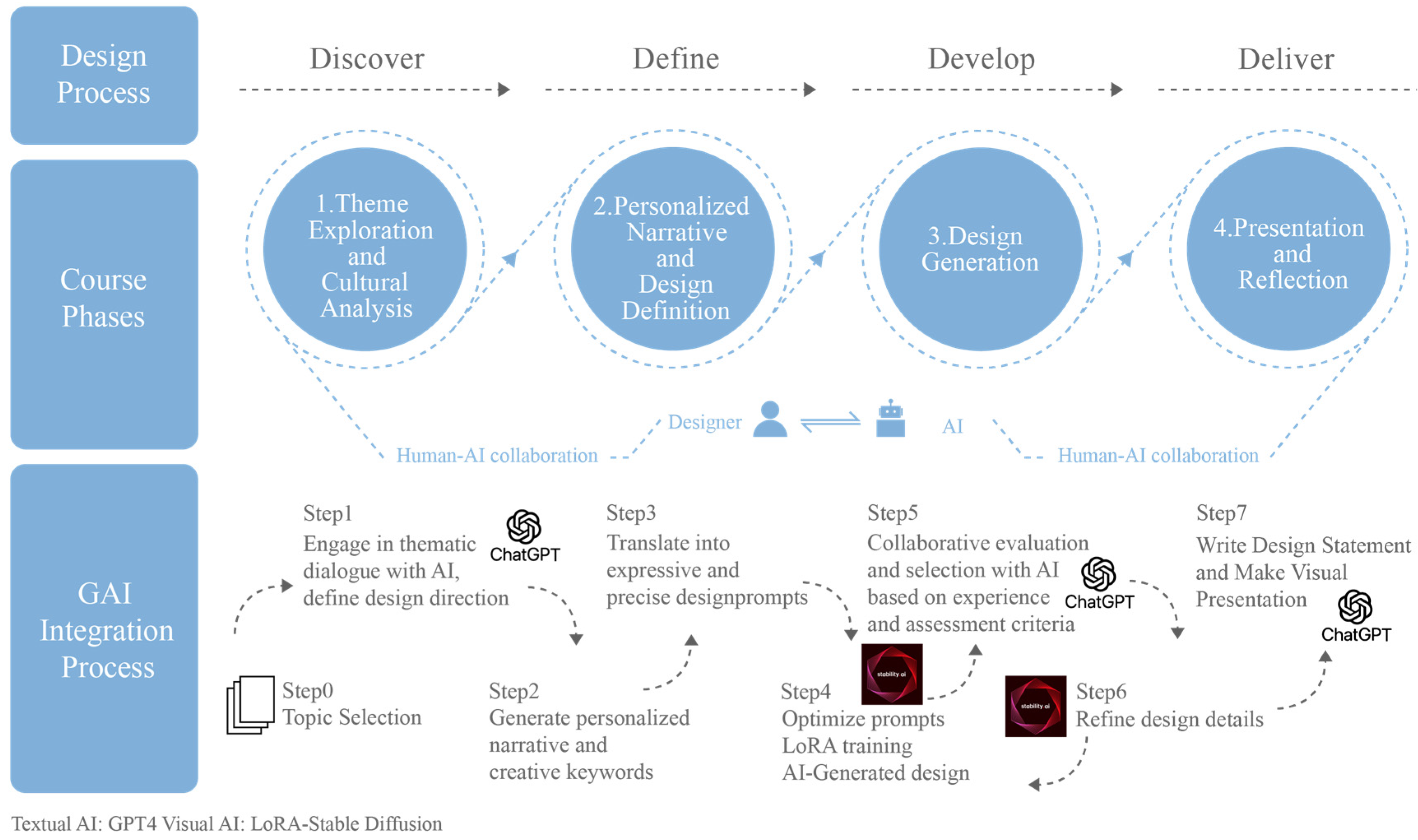

3.2.3. Customized GAI Tools

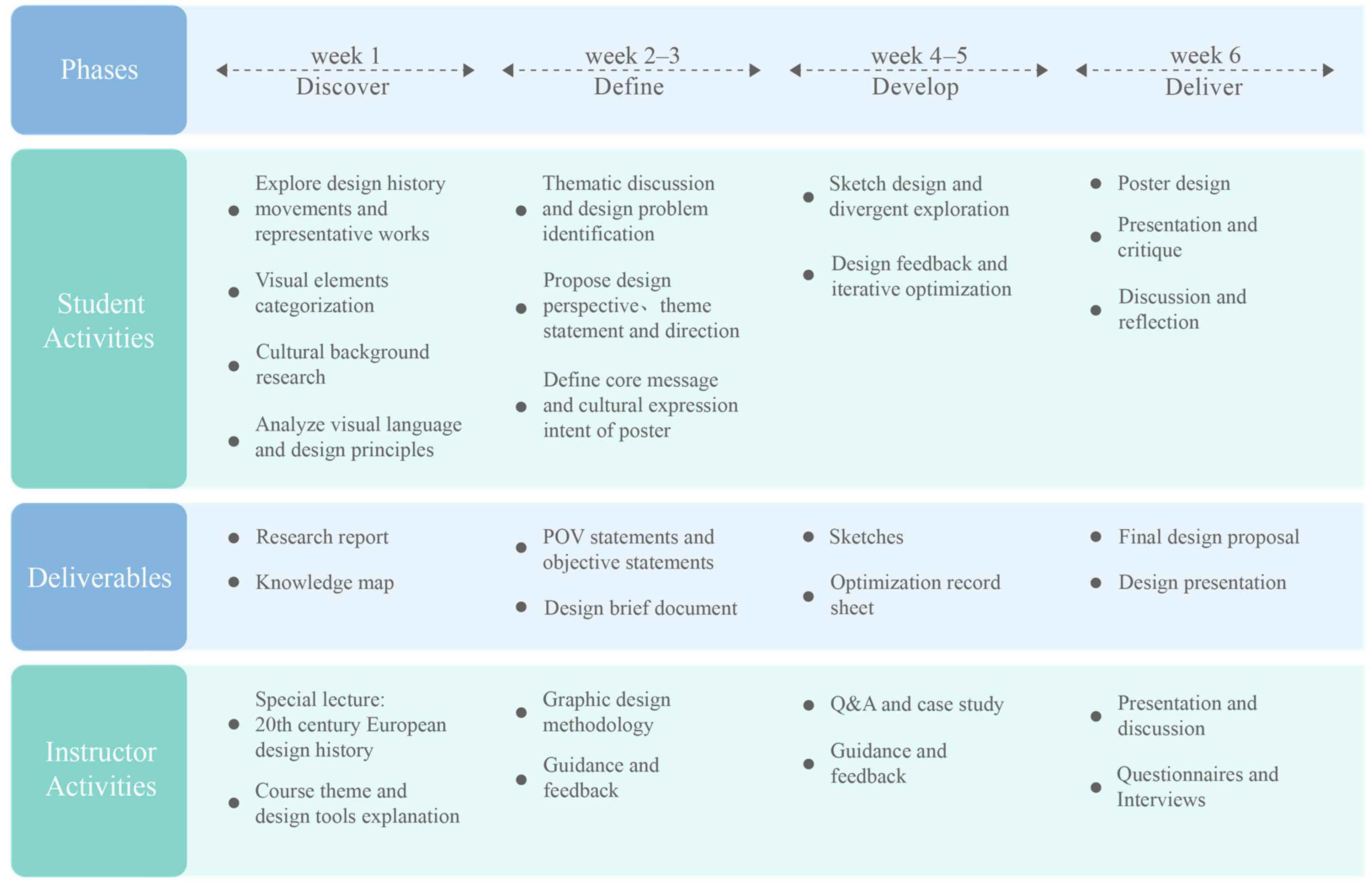

3.3. Course Design

3.4. Experimental Procedure

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Student Engagement Results

4.2. Emotional Analysis Results

4.2.1. Types of Customized GAI-Induced Emotional Experiences

4.2.2. Sources of Positive Emotions

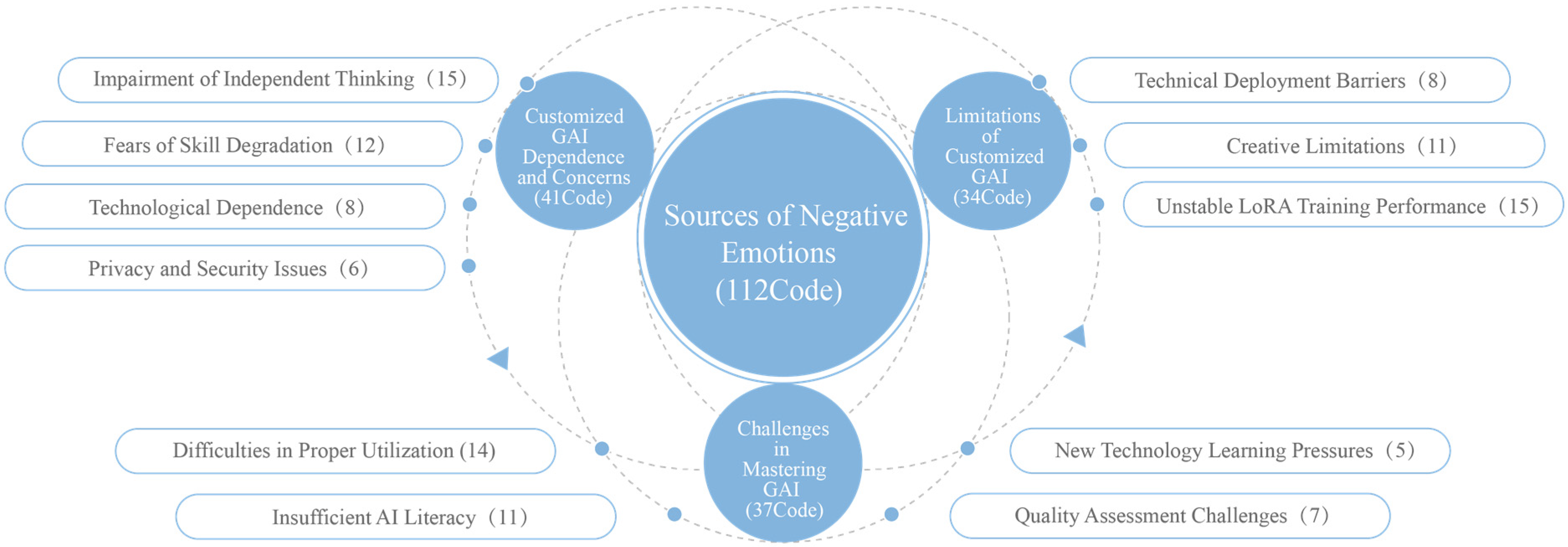

4.2.3. Sources of Negative Emotions

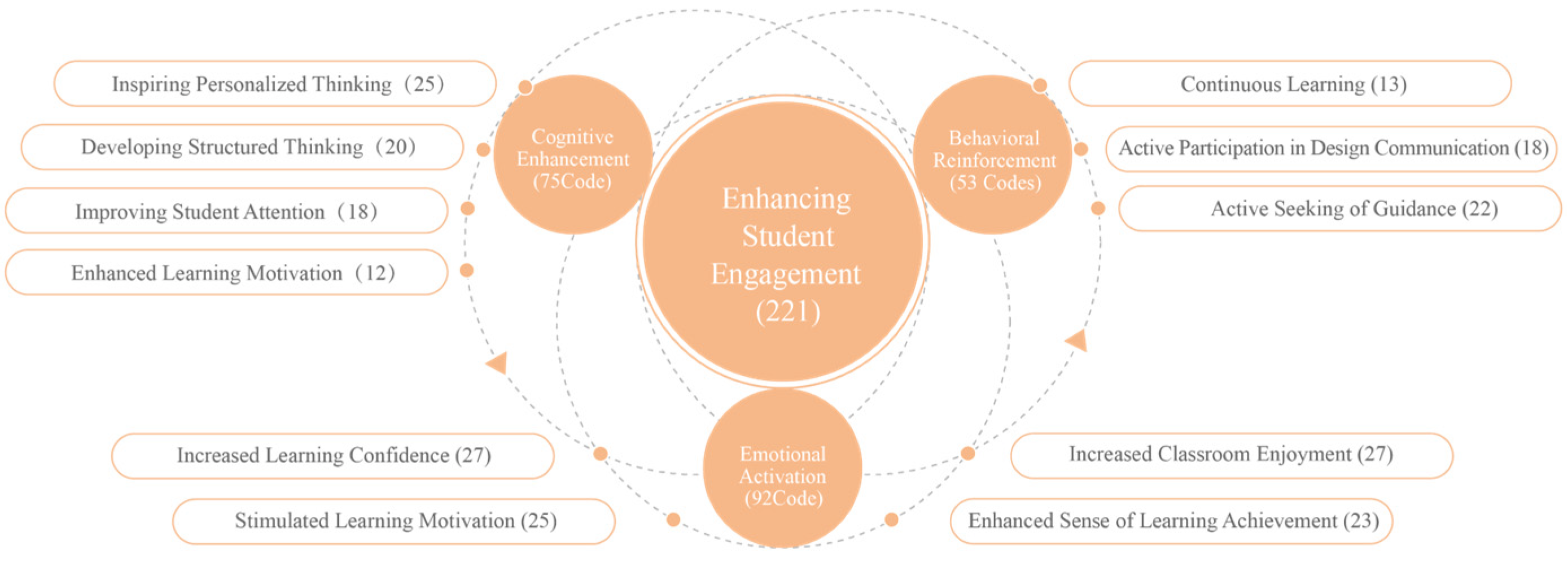

4.2.4. Enhancing Student Engagement

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| CVT | Control-Value Theory |

References

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in Education and Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386165 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Matthews, B.; Shannon, B.; Roxburgh, M. Destroy all humans: The dematerialization of the designer in an age of automation and its impact on graphic design—A literature review. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2023, 42, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shin, J. The impact of Gen AI on art and design program education. Des. J. 2025, 28, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, H.; Tedre, M. Using artificial intelligence in craft education: Crafting with text-to-image generative models. Digit. Creat. 2023, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicklighter, C.; Seo, J.H.; Andreassen, M.; Bujnoch, E. Empowering creativity with generative AI in digital art education. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Educator’s Forum; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, M.J.; Yuan, R. Exploring the integration of generative AI in advertising agencies: A co-creative process model for human–AI collaboration. J. Advert. Res. 2025, 65, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Buntins, K.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M. Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurma, O.A.; Albahti, F.; Ali, N.; Bustanji, A. AI ChatGPT and student engagement: Unraveling dimensions through PRISMA analysis for enhanced learning experiences. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2024, 16, ep503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. Pedagogical applications of generative AI in higher education: A systematic review of the field. TechTrends 2025, 69, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, G.M.; Heddy, B.C.; Lombardi, D. The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Tseng, C.-M. Agency as a Fourth Aspect of Students’ Engagement during Learning Activities. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.K.; Feng, C.H.; Liu, Y.L.E. Generative AI-Enhanced UX Storyboarding: Transforming Novice Designers’ Engagement and Reflective Thinking for IoMT Product Design. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fathi, T.; Saad, A.; Larhzil, H.; Al Ibrahmi, E.M. Integrating generative AI into STEM education: Enhancing conceptual understanding, addressing misconceptions, and assessing student acceptance. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 2025, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanyam, F.E.; Edeh, N.I.; Abanyam, V.A.; Obimgbo, J.I.; Nwokike, F.O.; Ugwunwoti, P.E.; Idris, B.A. Artificial intelligence: Interactive effect of Google Classroom and learning analytics on academic engagement of business education students in universities in Nigeria. Lib. Philos. Pract. 2023, 7703. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/7703 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Saritepeci, M.; Yildiz Durak, H. Effectiveness of artificial intelligence integration in design-based learning on design thinking mindset, creative and reflective thinking skills: An experimental study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 25175–25209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, L. Using AI-driven chatbots to foster Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement: An intervention study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 159, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisco, R.; Hay, L.; Dhami, S. Exploring the role of text-to-image AI in concept generation. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Holmes, W. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386693 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Sáez-Velasco, S.; Alaguero-Rodríguez, M.; Delgado-Benito, V.; Rodríguez-Cano, S. Analyzing the impact of generative AI in arts education: A cross-disciplinary perspective of educators and students in higher education. Informatics 2024, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.; Stephens, C.; Leach, L.; Zepke, N. Linking academic emotions and student engagement: Mature-aged distance students’ transition to university. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, A.; Graziani, D.; Bei, E.; Bischetti, L.; Bambini, V.; Gursesli, M.C. Emotional engagement in a humor-understanding reading task: An AI study perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 7818–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, M.; Lashari, T.A.; Akasah, Z.A.; Kesot, M.J. Self-efficacy, attitude, student engagement: Emphasising the role of affective learning attributes among engineering students. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, X. The effect of artificial intelligence tools on EFL learners’ engagement, enjoyment, and motivation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 162, 108474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, S. AI-Induced Emotions in L2 Education: Exploring EFL Students’ Perceived Emotions and Regulation Strategies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 159, 108337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Mei, Y.; Duh, H.; Zhou, Z. Envisioning the incorporation of generative artificial intelligence into future product design education: Insights from practitioners, educators, and students. Des. J. 2025, 28, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grájeda, A.; Córdova, P.; Córdova, J.P.; Laguna-Tapia, A.; Burgos, J.; Rodríguez, L.; Sanjinés, A. Embracing artificial intelligence in the arts classroom: Understanding student perceptions and emotional reactions to AI tools. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Mokmin, N.A.M. Unveiling the canvas: Sustainable integration of AI in visual art education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, A.F. Leveraging generative AI solutions in art and design education: Bridging sustainable creativity and fostering academic integrity for innovative society. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 426, 01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ni, C.; Lin, P.; Lin, R. Designing the future: A case study on human-AI co-innovation. Creat. Educ. 2024, 15, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, K. The commodification of creativity: Integrating generative artificial intelligence in higher education design curriculum. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Fu, X.; Zhao, J. Research on AIGC-integrated design education for sustainable teaching: An empirical analysis based on the TAM and TPACK models. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mokmin, N.A.M.; Su, H. Integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence into Design and Art Course: Effects on Student Achievement, Motivation, and Self-Efficacy. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Dong, M.; Lu, C. Integrating AIGC into product design ideation teaching: An empirical study on self-efficacy and learning outcomes. Learn. Instr. 2024, 92, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Jiang, X.; Deng, X.; Bian, Z.; Fang, C.; Zhu, Y. Comparing AIGC and traditional idea generation methods: Evaluating their impact on creativity in the product design ideation phase. Think. Ski. Creat. 2024, 54, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.K.; Turner, J.C. Discovering emotion in classroom motivation research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P.A.; Lanehart, S.L. Introduction: Emotions in Education. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Frenzel, A.C.; Götz, T.; Perry, R.P. Control-Value Theory of Academic Emotions: How Classroom and Individual Factors Shape Students Affect. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; AERA: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://kops.uni-konstanz.de/handle/123456789/36408 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Li, Y.; Chiu, T. The mediating effects of needs satisfaction on the relationship between teacher support and student engagement with generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) chatbots from a self-determination theory (SDT) perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 20051–20070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.E.; Lee, T.P.; Huang, Y.M. Enhancing student engagement and higher-order thinking in human-centred design projects: The impact of generative AI-enhanced collaborative whiteboards. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeoguine, E.P.; Eteng-Uket, S. Artificial intelligence tools and higher education student’s engagement. Edukasiana J. Inov. Pendidik. 2024, 3, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, I.S.; Sarwary, S.A.M.; El Refae, G.A.; Chabchoub, H. Time to revisit existing student’s performance evaluation approach in higher education sector in a new era of ChatGPT—A case study. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2023, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Phongsatha, S. An empirical study of the AI-driven platform in blended learning for Business English performance and student engagement. Lang. Test. Asia 2025, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoseni, A.; Kolade, O.; Egbetokun, A. Enhancing personalised learning and student engagement using generative AI. In Generative AI in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Ye, L.; Chen, M. The influence of educational psychology on modern art design entrepreneurship education in colleges. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 843484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lively, J.; Hutson, J.; Melick, E. Integrating AI-generative tools in web design education: Enhancing student aesthetic and creative copy capabilities using image and text-based AI generators. DS J. Artif. Intell. Robot. 2023, 1, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, S.; Zheng, J.; He, F. Enhancing visual communication design education: Integrating AI in collaborative teaching strategies. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2024, 24, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.; Hanson, W. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook on Mixed Methods in the Behavioral and Social Sciences; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Ge, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xu, W.; Mi, Y.; Hu, Z.; Gao, Y. A survey on LoRA of large language models. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 197605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Du, X. Vibration of creativity: Exploring the relationship between appraisal shift and creative process in design teams. Think. Skills Creat. 2024, 54, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.M.T.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Sutton, I.L. A model incorporating the rationale and purpose for conducting mixed-methods research in special education and beyond. Learn. Disabil. 2006, 4, 67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Wu, Y. The influence of generative artificial intelligence on creative cognition of design students: A chain mediation model of self-efficacy and anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1455015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacave, C.; Velázquez-Iturbide, J.Á.; Paredes-Velasco, M.; Molina, A.I. Analyzing the influence of a visualization system on students’ emotions: An empirical case study. Comput. Educ. 2020, 149, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creely, E.; Blannin, J. Creative Partnerships with Generative AI: Possibilities for Education and Beyond. Think. Skills Creat. 2025, 56, 101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Hu, W. Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.; Krishna, R.; Bernstein, M.; Gerstenberg, T. AI Overreliance Is a Problem: Are Explanations a Solution? Stanford HAI. 2023. Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ai-overreliance-problem-are-explanations-solution (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Passi, S.; Vorvoreanu, M. Overreliance on AI: Literature Review; Microsoft Research: Redmond, WA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/uploads/prod/2022/06/Aether-Overreliance-on-AI-Review-Final-6.21.22.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Kaitharath, M.F.; Shifna, K.N.; Anuradha, P.S. Generative AI and Its Impact on Creative Thinking Abilities in Higher Education Institutions. In Impacts of Generative AI on Creativity in Higher Education; Fields, Z., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wan Jaafar, W.M.; Sulong, R.M. Building better learners: Exploring positive emotions and life satisfaction as keys to academic engagement. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1535996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Tang, T.; Pu, L.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S. Teacher emotional support facilitates academic engagement through positive academic emotions and mastery-approach goals among college students. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241245369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, C.A. Regulation of Motivation: Evaluating an Underemphasized Aspect of Self-Regulated Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Engagement | Pre–Test | Post–Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Df. | Sig. | Statistic | Df. | Sig. | ||

| Experimental | BE 1 | 0.091 | 47 | 0.200 | 0.078 | 47 | 0.200 |

| EE 2 | 0.095 | 47 | 0.200 | 0.086 | 47 | 0.200 | |

| CE 3 | 0.118 | 47 | 0.147 | 0.115 | 47 | 0.148 | |

| Control | BE 1 | 0.089 | 47 | 0.200 | 0.112 | 47 | 0.197 |

| EE 2 | 0.106 | 47 | 0.200 | 0.121 | 47 | 0.142 | |

| CE 3 | 0.095 | 47 | 0.200 | 0.108 | 47 | 0.200 | |

| Group | Engagement | N | Pre Test | Post-Test | Change Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Δ Mean | 95% CI | |||

| Experimental | BE 1 | 48 | 3.911 | 0.528 | 4.198 | 0.561 | 0.286 | [0.167, 0.405] |

| EE 2 | 3.792 | 0.486 | 4.188 | 0.411 | 0.396 | [0.270, 0.522] | ||

| CE 3 | 3.757 | 0.541 | 4.229 | 0.533 | 0.472 | [0.386, 0.558] | ||

| Control | BE 1 | 48 | 3.865 | 0.491 | 3.948 | 0.418 | 0.083 | [−0.036, 0.202] |

| EE 2 | 3.776 | 0.457 | 3.734 | 0.559 | −0.042 | [−0.144, 0.060] | ||

| CE 3 | 3.733 | 0.469 | 3.753 | 0.543 | 0.020 | [−0.050, 0.090] | ||

| Mean (PRE) | Mean (POST) | Mean Difference | Std. Deviation | t-Value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE 1 | 3.911 | 4.198 | 0.286 | 0.419 | 4.737 | <0.001 |

| EE 2 | 3.792 | 4.188 | 0.396 | 0.446 | 6.147 | <0.001 |

| CE 3 | 3.757 | 4.229 | 0.472 | 0.304 | 10.752 | <0.001 |

| Mean (PRE) | Mean (POST) | Mean Difference | Std. Deviation | t-Value | p 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE 1 | 3.865 | 3.948 | 0.083 | 0.422 | −1.101 | >0.200 |

| EE 2 | 3.776 | 3.734 | −0.042 | 0.362 | 0.443 | >0.200 |

| CE 3 | 3.733 | 3.753 | 0.020 | 0.246 | −0.317 | >0.200 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 2.856 | 2 | 1.428 | 12.25 | <0.001 | 0.208 |

| Pre-BE (covariates) | 0.975 | 1 | 0.975 | 8.36 | <0.01 | 0.082 |

| Group | 1.881 | 1 | 1.881 | 16.13 | <0.001 | 0.148 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 4.329 | 2 | 2.165 | 17.28 | <0.001 | 0.208 |

| Pre-EE (covariates) | 2.482 | 1 | 2.482 | 19.81 | <0.001 | 0.082 |

| Group | 1.847 | 1 | 1.847 | 14.74 | <0.001 | 0.116 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 4.892 | 2 | 2.446 | 22.79 | <0.001 | 0.329 |

| Pre-CE (covariates) | 2.634 | 1 | 2.634 | 24.55 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| Group | 2.258 | 1 | 2.258 | 21.04 | <0.001 | 0.185 |

| Emotional Experiences | Categories | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (235 codes) | Excitement | 38 | 16.2 |

| Satisfaction | 32 | 13.6 | |

| Curiosity | 29 | 12.3 | |

| Pleasure | 28 | 11.9 | |

| Enjoyment | 26 | 11.1 | |

| Confidence | 25 | 10.6 | |

| Surprise | 23 | 9.8 | |

| Pride | 19 | 8.1 | |

| Anticipation | 15 | 6.4 | |

| Negative (112 codes) | Stress | 26 | 23.2 |

| Doubt | 22 | 19.6 | |

| Worry | 18 | 16.1 | |

| Confusion | 15 | 13.4 | |

| Anxiety | 12 | 10.7 | |

| Frustration | 10 | 8.9 | |

| Fear | 5 | 4.5 | |

| Disappointment | 4 | 3.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Sun, L.; Kim, S. Effects of Customized Generative AI on Student Engagement and Emotions in Visual Communication Design Education: Implications for Sustainable Integration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229963

Li H, Sun L, Kim S. Effects of Customized Generative AI on Student Engagement and Emotions in Visual Communication Design Education: Implications for Sustainable Integration. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229963

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, He, Liang Sun, and Seongnyeon Kim. 2025. "Effects of Customized Generative AI on Student Engagement and Emotions in Visual Communication Design Education: Implications for Sustainable Integration" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229963

APA StyleLi, H., Sun, L., & Kim, S. (2025). Effects of Customized Generative AI on Student Engagement and Emotions in Visual Communication Design Education: Implications for Sustainable Integration. Sustainability, 17(22), 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229963