1. Introduction

Current human activities are nearing critical thresholds of planetary boundaries [

1], resulting in a triple ecological crisis at both global and regional levels. This crisis manifests in three major ways: first, the impending collapse of the climate system, as global temperatures approach the 1.5 °C limit established by the Paris Agreement; second, the current global rate of species extinction evidenced by the IPBES Global Assessment Report (2019) is at least tens to hundreds of times faster than the average rate observed over the past 10 million years; and third, significant pollution overload, jeopardizing the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) sub-target 14.1—aimed at preventing and significantly reducing marine pollution by 2025—and resulting in the failure to meet SDG target 15.2, which seeks to promote sustainable management of forests and halt deforestation by 2020. From a domestic perspective in China, statistics released by the Supreme People’s Court in its China Environmental Resources Judgments (2021–2024) report reveal that, from 2021 to 2024, the People’s Courts lawfully concluded 265,341, 246,104, 231,830, and 219,000 first-instance environmental resources cases, respectively. The frequent occurrence of environmental infringement cases not only threatens ecosystem stability and public health, but also undermines the effectiveness of judicial governance, ultimately hindering regional economic sustainability. In this context, legal responses must be designed to directly address these underlying structural causes. Javier Morán Uriel et al. provide an in-depth analysis of the relationship between urban expansion, population density changes, and regional development policies [

2]. These structural changes have driven the rise of environmental infringement disputes.

Punitive damages play a crucial role in advancing ecological sustainability and ecological civilization. They not only mitigate the limitations of traditional compensatory measures but also significantly heighten the costs associated with environmental torts, thereby deterring pollution and ecological damage. This internalization of negative externalities fosters a strong deterrent effect and provides sustained financial support for comprehensive, long-term ecological restoration initiatives. The Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China (2020) (hereinafter referred to as the “Civil Code (2020)”) and the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court regarding the application of punitive damages in ecological environment tort disputes (2022) (hereinafter referred to as the “Interpretation (2022)”) have laid the groundwork for the institutional framework governing punitive damages in environmental torts. However, specific rules remain contentious and insufficient, particularly concerning unclear definitions of punitive damages, ambiguous calculation rules (including base amount determination and multiplier application), inconsistent damage allocation, lack of distribution priority rules, and the failure to establish offset mechanisms for criminal fines and administrative penalties. Controversies and inadequacies in regulations often occur in the absence of robust “damage quantification tools.” European regions have pioneered ecological mapping through ecosystem assessments, such as the Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services (MAES), which translates environmental damage into spatially defined “ecological liabilities.” This approach provides an actuarial foundation for assessing punitive damages. Rafael Córdoba Hernández et al. propose a methodology for integrating ecosystem assessments, such as MAES, into land-use planning. Through a three-step evaluation framework—presenting spatial ecosystem information, proposing assessment methods, and evaluating the impacts of land-use planning—the authors translate ecosystem degradation into quantifiable “ecological deficits,” thereby providing a computational foundation for determining legal liability [

3]. Currently, China is currently experiencing a critical phase of rapid urbanization and the spatial redistribution of resources. Environmental pollution and ecological degradation are not merely matters of “violation-compensation,” but rather systemic risks arising from “spatial imbalances and capacity depletion.” This study aims not only to refine the rules for punitive damages in environmental torts but also marks the first systematic proposal in China to integrate ecological spatial mapping into the determination of compensation factors. This novel approach translates abstract legal requirements into verifiable spatial evidence, thereby providing the judiciary with precise and operational technical supports and methodological tools.

From the perspective of ecological sustainability, this study reflects the inclusive principle of “leaving no one behind” from the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the intergenerational equity requirement outlined in the Rio Declaration, the goal of “halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030” established in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, and the vision of “living in harmony with nature by 2050” set forth in the Convention on Biological Diversity. This study systematically examines China’s existing punitive damages rules for environmental torts, addressing current controversies and deficiencies through an analysis of key aspects such as the definition of nature, calculation rules, allocation arrangements, distribution priorities, and offset mechanisms with criminal fines and administrative penalties, proposing pathways for improvement oriented toward ecological sustainability. Additionally, this research aims to provide a “Chinese approach” to the construction of relevant global and regional institutions while enriching the theoretical framework surrounding these rules.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Basis

Ecological sustainability is fundamentally about achieving a balance between human development and the preservation of the natural environment. This concept has evolved from an early focus on ecosystem carrying capacity as highlighted by Goodland [

4], through to considerations of ecosystem services and integrity by Faveret et al. and Min Qingwen et al. [

5,

6], and extending to Lü Zhongmei’s framework for a harmonious coexistence between humans and nature [

7]. Despite varying perspectives, the underlying premise consistently emphasizes the importance of accommodating human development within the limits of ecological carrying capacity. In line with this unified understanding, this study defines ecological sustainability as the fulfillment of current development needs while strictly limiting human activities to those that the ecosystem can sustainably support, thereby preserving ecosystem health, biodiversity, and ensuring that resource extraction does not surpass natural regeneration rates. This framework ultimately seeks to establish a sustainable and harmonious relationship between humans and the environment. The myriad roles ecosystems play—such as maintenance, regulatory functions, provisioning, and resilience—form an essential ecological base that supports the equilibrium between environmental conservation and societal progress [

8,

9,

10].

In a related vein, environmental torts, identified as specific legal wrongs that entail liability for harming others’ rights to person or property through environmental contamination or ecological destruction, necessitate the evolution of legal remedies. Originating in the 18th century from the Wilkes case in England [

11]—initially addressing illegal searches, seizures, and detentions [

12]—punitive damages have been extensively applied within Common Law jurisdictions, especially in the United States, as shown in the Zarcone case [

13]. Their adoption into environmental law marks a shift from mere compensatory remedies towards a multifaceted governance tool that integrates punishment, deterrence, and incentives. This study characterizes punitive damages in environmental tort cases as monetary compensation that exceeds actual losses, awarded by courts upon a plaintiff’s request against a defendant who intentionally commits acts damaging the environment, thereby causing significant ecological harm and infringing upon the lawful rights and interests of individuals. Such measures not only address the inadequacies of purely compensatory methods in tackling the enduring and latent impacts of environmental harm but also serve to deter future infractions by escalating the financial consequences [

14], facilitating both specific and general prevention of environmental offenses [

15]. This approach aligns with the pressing demands for environmental protection, encourages claimants to actively pursue their rights, boosts public environmental consciousness, and supports the development of an ecological civilization, effectively embedding the imperatives of ecological sustainability within economic decision-making through judicial avenues.

To effectively enhance China’s punitive damages framework for environmental torts, a systematic exploration of the institutional logic and constraints across different legal traditions within a coherent comparative law framework is essential, providing a foundation for crafting context-specific legal mechanisms.

2.1. The “Quantitative Balancing” Model in Common Law Systems: Technocratic Control Centered on Judicial Practice

In common law jurisdictions, punitive damages are governed by judicial methods that aim to achieve a case-specific balance, focusing on two primary concerns: the factors for assessment and the limits on the amount awarded. With respect to assessment factors, UK law mandates that juries meticulously evaluate several elements, including the tortfeasor’s degree of fault, potential defenses, and financial capacity. The Law Reform Commission has also advised incorporating additional factors such as the number of implicated parties, the tortfeasor’s gains from the wrongdoing, and pertinent elements from the European Convention on Human Rights into assessments [

16]. In the United States, the South Dakota Supreme Court delineated five categories for consideration: the nature and gravity of the misconduct, the sum of compensatory damages awarded, the defendant’s mental state, their financial status, and other relevant circumstances [

17]. The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals expanded these categories in the Read case to include the defendant’s organization size, any corrective measures taken, attempts to hide the misconduct, and the duration of the misbehavior [

18]. Additionally, both the Restatement (Second) of Torts and the Model Punitive Damages Act integrate factors such as the extent of harm and other penalties imposed on the defendant to refine the assessment of culpability and societal impact.

Regarding limits on damages, while some scholars argue for the elimination of caps to better protect victims’ rights [

19], legal practice commonly employs proportional limits, set amounts, or hybrid systems to deter excessive awards. The UK Court of Appeal advises that punitive damages should not typically surpass triple the actual loss. In the U.S., constraints involve mechanisms based on the principle of proportionality, such as a multiple relationship between punitive and compensatory damages, statutory caps like the

$350,000 limit in Virginia, or a combination thereof, established through constitutional jurisprudence and state laws [

20]. This reflects a careful equilibrium between the need for punishment and the prevention of undue excess.

It is noteworthy that the deterrent effectiveness of punitive damages in the United Kingdom is not “comprehensively applicable.” According to a comprehensive regression analysis conducted by James Goudkamp et al. on 146 first-instance claims in the UK between 2000 and 2015 [

21], punitive damages in the UK exhibit characteristics of selective deterrence at the empirical level. The findings indicate that punitive damages demonstrate significant deterrent effects in cases involving insurance fraud and unlawful eviction: the success rate for insurance fraud cases reached 88.9%, while property torts recorded a success rate of 53.8%, with an average award of £12,625. By contrast, police misconduct cases had a success rate of only 25%, with awards below the average, and no rulings were issued in media tort cases. In the United States, the deterrent effectiveness of punitive damages appears stable yet marginal. According to Theodore Eisenberg et al. [

22], who analyzed state court data from 539 cases between 1992 and 2001 in which plaintiffs prevailed and received punitive damages, the overall award rate for punitive damages was only 4.6%. More than 60% of these awards were below USD 100,000, with the median punitive-to-compensatory ratio around 1:1, suggesting limited deterrent strength. In non-personal injury cases, jury award rates reached 11.6%, significantly higher than the 3.5% rate for judges, creating localized deterrence against commercial fraud and breaches of trust. In personal injury cases, judges rendered punitive damages in 6.1% of cases, while juries did so in 2.2%, indicating a modest restraining effect on repeat offenders.

2.2. The “Constitutional Constraint” Model in Civil Law Systems: A Focus on Proportionality

Historically, Civil Law systems have eschewed punitive damages, considering them more suited to public law [

23]. The European Commission has explicitly barred punitive damages in civil litigation through its Recommendation on Common Principles for Collective Redress [

24]. However, the growing trend of “publicizing private law” has seen Civil Law regions beginning to accommodate punitive damages in a restricted capacity, using proportionality as a cornerstone constitutional review tool.

Article 52 (1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000) and Articles 8–11 of the European Convention on Human Rights (1950) mandate that any limitation on citizens’ rights adhere to the principle of proportionality. German scholar Lothar Hirschberg et al. articulated this principle as a three-tier test: suitability, necessity (requiring the least restrictive means), and proportionality in the strict sense (involving a balancing test) [

25]. Within the punitive damages framework, the suitability principle necessitates a legitimate connection between the damages and the objectives of punishment and deterrence [

26]. The necessity principle favors methods that inflict the minimal harm necessary to achieve these goals [

27]. The balancing principle strictly requires that the damages are commensurate with the severity of the conduct. The Italian Supreme Court emphasized that punitive damages must align with principles of legality (per Articles 23 and 24 of the Constitution) and proportionality, guarding against judicial overreach [

28]. France has also adopted proportionality assessments when recognizing foreign punitive damages judgments [

29]. Therefore, the principle of proportionality in Europe has evolved beyond a mere technical guideline, becoming a constitutional benchmark for the legality of punitive damages. The proportionality principle, as a fundamental constraint within the civil law system, effectively balances the protection of individual rights with the prevention of excessive deterrence. However, its actual deterrent effect warrants further empirical investigation, particularly through specific case studies.

2.3. China’s “Pragmatic Expansion” Model: Problem-Oriented Development Driven by Legislation

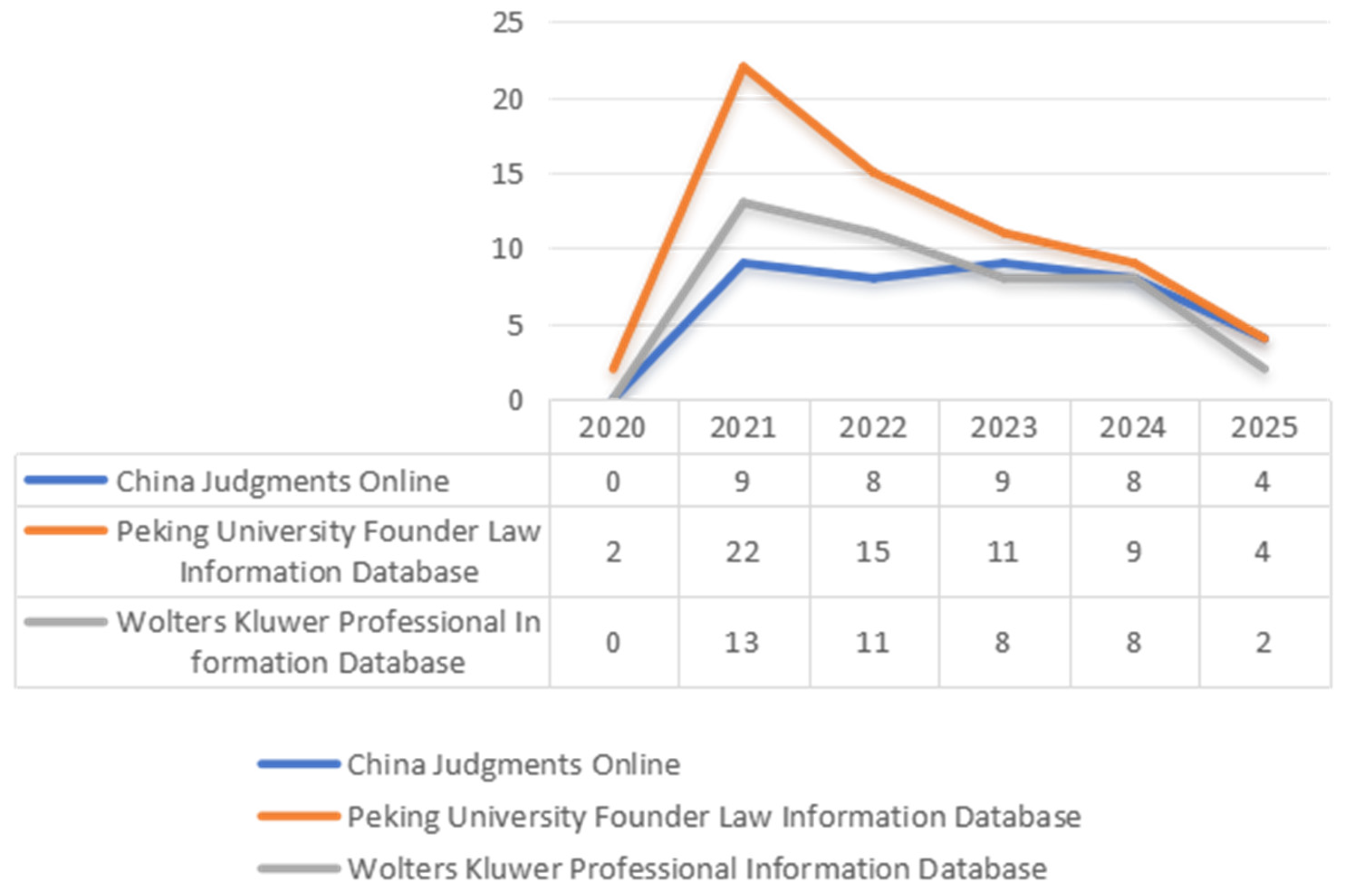

China’s punitive damages regime has evolved through a pragmatic and incremental approach since its inception. Initially introduced in the 1993 Consumer Rights Protection Law via the “return one, compensate one” rule, its application has expanded to areas such as food safety, intellectual property, and ecological environment (see

Table 1). The consolidation of this regime occurred in the Civil Code (2020), specifically Article 1232, which delineates the conditions under which punitive damages apply to environmental torts. A further refinement was made in 2022 when the Supreme People’s Court provided a judicial interpretation that detailed the constitutive requirements and methodology for calculating damages. Yet, despite these developments, scholarly focus has largely remained on theoretical explorations of the system’s nature, eligible claimants, and fundamental components, with a particular neglect of the practical rules governing damage amounts. This discrepancy persists across various elements of punitive damage calculations:

Calculation Model: Zhou Ke et al. suggest implementing both upper and lower limits to promote effective rights protection, contrasting with Zhang Xueqing’s position advocating for only an upper limit to prevent excessive liability. Calculation Base: Zhou Xiaoran recommends using actual loss as the base, a stance refined by Yang Lixin, who argues for the exclusion of litigation costs. Alternatively, some argue for employing environmental remediation costs or the loss of interim ecosystem services as benchmarks [

30,

31,

32]. Multiplier Setting: There is debate over whether multipliers should vary between private and public interest environmental lawsuits, with some advocating for differentiated ranges [

33] and others supporting a uniform standard. Assessment Factors: Article 10 of the Interpretation (2022) lists certain factors, but scholars propose a broader array including the wrongdoer’s illicit gains, subjective state, and previously imposed penalties, signaling a lack of consensus [

34,

35].

Despite this detailed theoretical framework, empirical research addressing deeper issues like the nature of damages, allocation mechanisms, and the interplay with criminal and administrative sanctions remains limited. An empirical study by Song Fei et al., based on 512 Chinese judicial cases involving ecological and environmental restoration liability, identifies practical challenges such as difficulties in executing restoration projects, unclear allocation of responsibility, and ambiguity in identifying litigation parties [

36]. These obstacles also hinder the full operation of the punitive damages system. In cases where the liable party is uncertain or the destination of compensation funds is unclear, the enforcement of high punitive damages may encounter difficulties, thus diminishing the system’s effectiveness.

2.4. Pathways for Refining China’s System from a Comparative Perspective: Technical Borrowing and Doctrinal Coherence

Improving China’s punitive damages system for environmental torts necessitates a grounded approach tailored to localized practices while integrating the technical refinements of common law and the principled constraints of civil law to foster synergistic innovation via ‘technical borrowing’ and ‘doctrinal coherence’.

On the front of technical borrowing, China may draw from common law precedents which address the intricacies of environmental harm. This entails enhancing the criteria for damage assessments by incorporating factors such as the tortfeasor’s degree of fault, illicit gains, and the impacts on ecosystem services. The implementation of an elastic range system with graded multiplier brackets determined by the severity of the offense could improve both predictability and discretionary flexibility. Regarding doctrinal coherence, the civil law principle of proportionality should be integrated, adopting ‘ecological sustainability’ as a criterion for assessing a legitimate purpose. This integration ensures that the quantum of damages correlates with the gravity of the tortious act, the tortfeasor’s fault, and any remedial actions undertaken. This assessment can follow a three-step test: suitability, examining whether the damages fulfill the objectives of ecological protection and deterrence; necessity, determining if the penalty is the minimum required to meet these objectives; and balancing, ensuring that the damages are commensurate with both the inflicted harm and the tortfeasor’s financial capacity. Moreover, there is an urgent need for empirical research to explore the application of punitive damages in specific instances, their deterrent effects, and their coordination with administrative and criminal penalties. Such studies will provide an empirical basis for further refining the punitive damages system.

4. Improving the Rules on Punitive Damages for Environmental Tort Towards Ecological Sustainability

4.1. Clarifying the Nature of Punitive Damages for Environmental Tort

The nature of punitive damages for environmental tort should be categorized as private law claims. From a legal perspective, the primary objective of instituting this system is to remedy private interests [

61]. Article 1232 of the Civil Code (2020) restricts the claimants to “victims,” rejecting the vertical “state-tortfeasor” dynamic described by public law claim theory and providing substantive legal backing for its classification as a private law claim. Functionally, punitive damages serve to implement the principle of full compensation, addressing damages not accounted for by conventional compensatory damages. The “Hand Formula” (prevention cost B < accident probability P × damage result L) in law and economics posits that if the cost of preventive measures is less than the expected accident loss, an obligation to take prevention arises. By internalizing social costs into the tortfeasor’s responsibilities, punitive damages help deter intentional neglect of preventive measures, fostering behaviors that protect social efficiency [

62]. If punitive damages were characterized as public law claims, the risk of duplicated punishment could arise from the overlap with criminal fines and administrative penalties. Procedurally, while punitive damages litigation may attain certain public law objectives via private law channels, it adheres to civil litigation norms, such as equality and party autonomy in asserting claims. In environmental civil public interest litigation, even if the plaintiff is not the directly harmed party, the nature of the litigation remains civil, asserting civil rights [

63]. From a systemic coordination standpoint, punitive damages can be viewed through the lens of a “compensatory punishment” segment and a segment reflecting “excessive deterrence.” The former aims to recompense actual losses and excludes any offset, while the latter aligns with penalties or fines and allows for offsets. Offset discussions are purely focused on the allocation of amounts rather than altering claim ownership. Article 10, paragraph 2 of the Interpretation (2022) stipulates that the amount of punitive damages should be “comprehensively considered” when criminal or administrative responsibilities have been assumed, which indirectly denies the characterization of public law claims, otherwise the principle of “no punishment for one thing” can be directly applied. If it is not allowed to offset, it may lead to an excessive burden on the infringer, which will affect environmental restoration and compensation for the victims. The mixed theory of public and private law does not really respond to the subject of claim and the right of disposition, so it is not suitable for adoption.

4.2. Clarifying the Calculation Rules for Punitive Damages for Ecological Environment Tort

To accurately quantify ecological value into specific compensation amounts, establishing precise, operable, and balanced calculation rules is essential. This approach aims to internalize environmental costs, deter potential pollution, and secure resources for ecological restoration—directly supporting sustainability goals regarding damage prevention and ecological recovery.

4.2.1. Unifying Base Amount Identification and Quantification

Initially, the identification of base amounts should be standardized. The calculation base must strictly limit itself to personal injury, property loss, interim service function loss, and permanent damage resulting from environmental pollution or ecological degradation, excluding environmental restoration costs. Its basis lies in: on the one hand, the Civil Code (2020), Interpretation (2022) and other laws and regulations clearly distinguish the environmental restoration costs from the aforementioned losses, and the two should not be confused. On the other hand, the interim service function loss and permanent damage loss directly reflects the loss of ecological value, which is highly consistent with the disciplinary purpose of punitive damages. Limiting the base to such losses and strictly limiting the compensation multiple (less than 2×) will help to prevent excessive punishment, achieve a balance between punishment, restoration and development, and meet the goal of ecological sustainable development. To enhance consistency in setting baseline amounts across judicial practices, the Supreme People’s Court should revise the Interpretation (2022) by incorporating specific provisions. These provisions should adopt a “negative list” methodology to definitively exclude ineligible expenses, such as costs for environmental restoration, and use a “positive list” to clearly define eligible components of compensation, including personal injury, property damage, temporary functional loss of services, and permanent impairment. Moreover, it is advisable to introduce “Guidelines on Calculating Punitive Damages for Ecological and Environmental Torts (hereinafter referred to as the “Guidance”).” These guidelines should require all courts to explicitly refer to these punitive measures in their rulings, providing a detailed justification for each component of the baseline amount and the evidence supporting it. Non-compliance should be grounds for retrial or case reversal.

Next, the methods of quantifying the base amount should be standardized. To resolve existing ambiguities and strengthen operability, it is recommended: First, strengthen the legal framework. Relevant laws and regulations need revision, and the Supreme People’s Court should provide a uniform clarification of the definition of interim service function loss in the accompanying Guidelines. Second, refine technical standards by issuing detailed guidelines that clarify assessment procedures, methodologies, and formula parameters for different damage types. Third, delineate priority orders for quantification, providing a structured approach based on ascending criteria. For the same damage type, priority reference of interim service function loss basis during quantification under the same damage type: official data such as technical guidelines-occupation standard-regional market transaction data-alternative regional analogy data-model simulation data-virtual treatment cost adjustment coefficient (see

Table 4). Fourth, break through professional barriers. (1) Implement a Structured Capacity Building Program for Environmental Adjudication. The Supreme People’s Court and Supreme People’s Procuratorate should collaborate with the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and leading research institutions to initiate a structured environmental education program tailored for judges and prosecutors. This initiative must encompass a compulsory course named “Environmental and Resource Adjudication Practice,” delivering at least 60 credit hours of training. The curriculum is designed to emphasize practical skills, including the interpretation of appraisal reports, the cross-verification of quantification methods, and the evaluation of parameter reasonableness, thereby extending beyond mere theoretical knowledge. The implementation strategy consists of three phases: Pilot and Voluntary Participation Phase: Begin with pilot projects in economically advanced provinces with high incidences of environmental litigation, such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian. This phase encourages voluntary participation, with completion of the training serving as a criterion for appointing presiding judges in significant, complex environmental cases or for inclusion in specialized adjudication teams. Standardization and Talent Pool Development Phase: Utilize insights from the initial pilots to develop standardized training curricula, assessment standards, and certification procedures, thereby creating a cohesive national framework. Limited Integration with Career Progression Phase: As acceptance and reliability of the training system are established, incorporate it as a preferred qualification for leadership positions within environmental divisions or as a consideration in judicial promotions. (2) Promote Standardized Procedures for the Participation of Environmental Expert Assessors. The Ministry of Justice, in conjunction with the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, should establish an “Expert Database for Environmental Adjudication Technology.” This platform should feature rigorous criteria for expert admission and selection procedures. In cases classified as major or complex, courts must use the expert assessor system, selecting assessors randomly from this database. The role of these experts will primarily involve providing assessments on technical matters, such as the quantification of damages. Importantly, their professional judgements should be meticulously documented in the records of the collegiate panel, thus enhancing the scientific validity of the adjudications at an organizational level.

4.2.2. Unifying Multiplier Determination

Initially, to address inconsistencies in base amount identification, private interest litigation should utilize “personal injury” and “property loss” as the base; civil public interest litigation should apply “interim service function loss” and “permanent damage loss,” explicitly excluding “environmental restoration costs.” The quantitative basis of “interim service function loss” shall strictly follow

Table 4.

Moreover, to address the inconsistency in judges not adhering to the “base amount × multiplier” calculation method for punitive damages, it is imperative that the Supreme People’s Court specify in its “Guidance” that this formula is the definitive statutory method. This clarification will eliminate ambiguous practices such as discretionary determinations. Furthermore, judgment documents must adhere to a mandatory three-step process: confirming the multiplier through technical analysis, performing the multiplication, and comprehensively documenting each step of the computation, including all relevant data sources such as appraisal reports and third-party audits to ensure the calculation’s traceability and verifiability. Additionally, the “Guidance” shall mandate a specific hierarchy for quantifying key base amounts, such as ‘interim service function loss.’ This hierarchy must apply existing technical standards in a prescribed sequence—prioritizing national standards, followed by industry standards, and finally authoritative academic models—to prevent significant assessment discrepancies arising from methodological differences (see

Table 4). When determining the multiplier, a structured correlation between ‘consideration factors and their quantified weights’ must be established (see

Table 5). It is crucial that judges explicitly list and explain each statutory factor in their rulings—factors such as the degree of malice, the extent of harm, benefits obtained, and the efficacy of remedial measures—and detail how these considerations influence the calculation of the final multiplier value. This explicit documentation ensures transparency and adherence to the stipulated punitive damages calculation framework.

Lastly, in view of the lack of minimum multiple for punitive damages in environmental private interest litigation and the lack of multiple provisions for punitive damages in environmental civil public interest litigation, the minimum multiple of environmental infringement can be set to 1 on the basis of clear base selection and quantification [

64], and consideration of factors and weights. At the same time, it is suggested that the first paragraph of Article 10 of the Interpretation (2022) be amended as: but generally not less than personal injury compensation, twice the amount of property losses, and not more than twice the amount of personal injury compensation and property losses. Article 12 is added: but generally, it shall not be less than twice the amount of loss caused by loss of service function during the period from ecological environment damage to restoration completion, nor more than twice the amount of loss caused by loss of service function during the period from ecological environment damage to restoration completion.

4.2.3. Unifying Consideration Factors and Their Weights

The selection of consideration factors for punitive damages should emphasize the primary goal of achieving equitable punishment for environmental torts while safeguarding individual freedoms. It is crucial that punitive damages are positively correlated to the culpability of the tortious behavior [

65]. This analysis proposes evaluating punitive damages based on various influencing factors, as outlined below. The foremost elements of subjective malice, damage scale, and severity of damage should retain prominence during evaluations. This study proposes incorporating ecological spatial mapping into the assessment of factors considered in environmental tort compensation claims. By overlaying the coordinates of infringing activities with GIS layers representing eight categories of protected areas—including national nature reserves, natural and cultural heritage sites, national scenic areas, national geoparks, national forest parks, national conservation areas, priority conservation zones, and key ecological function zones—it seeks to provide verifiable spatial evidence for evaluating “intentional misconduct,” “permanent damage,” and “environmental remediation measures and outcomes.”

(1) The degree of subjective malice. Punitive damages for environmental tort require stricter subjective fault than general tort liability, and are limited to “intentional”, that is, knowingly and intentionally pursuing or letting damage happen, including direct intentional and indirect intentional, excluding gross negligence [

66]. The higher the degree of subjective malice, the higher the amount of punitive damages. Subjective malice can be judged from three aspects: first, the nature, frequency and duration of behavior, and bad, frequent or long-lasting behavior reflects high malice [

67]. Second, whether there is re-offending or recidivism, and repeated infringement shows disregard for the law; Third, whether there is any act of concealing or forging evidence, which can be presumed to be intentional. Furthermore, the degree of subjective malice can be evaluated using a two-step method consisting of ‘spatial overlay analysis’ followed by a ‘procedural legality review’. Initially, the precise coordinates of the infringing activity are overlaid with GIS layers of eight different types of protected zones in China, including nature reserves and natural/cultural heritage sites, to determine the extent of overlap with these red-line zones. If the overlap is 80% or more, it is presumed that there was knowledge of the infringement. For overlaps ranging from 50% to 80%, a judgment of “should have known” is inferred, supported by documentary evidence such as environmental impact assessment approvals and planning permits. Conversely, if the overlap is 50% or less, evidence of intent must be corroborated by additional proof, such as satellite remote sensing, nighttime infrared data, or enforcement records that illustrate covert methods like hidden pipelines or secret discharges. Additionally, projects situated in ecologically sensitive areas along national or cross-provincial boundaries, initiated without authorization from the national-level ecological and environmental authority, are considered highly malicious, warranting the assignment of the highest possible multiplier within the weighting range.

(2) The scale of damage. Paragraph 1 of Article 8 of the Interpretation (2022) lists the scale of damage as the primary basis for determining “serious consequences”. Specific measurement can be carried out from three aspects: first, the polluted area can be determined by satellite remote sensing and geographic information system, and the larger the area, the higher the compensation. Second, the total amount of pollutants needs to be evaluated by means of mass balance method and fingerprint, and the chemical properties of highly toxic substances (such as PFAS and dioxin) should also be considered. Third, the number of sensitive receptors can be quantified by population exposure model or ecological service value assessment.

(3) The severity of the damage. Environmental infringement must cause “serious consequences” before punitive damages can be applied. Article 8 of the Interpretation (2022) makes it clear that “serious consequences” in private interest infringement include death, serious health damage or major property losses, and public welfare infringement refers to “serious damage to the ecological environment or significant adverse social impact” [

68]. Judging the severity of damage can be based on the following three aspects: first, public health effects, such as death or organ function damage, can be directly identified as serious consequences, but the general impact on psychological or physiological functions is still controversial [

69]. The second is the loss of service function and permanent damage during the period, which are often used as the base for calculating compensation. The third is whether the environmental damage is reversible. The lower the reversibility, the more serious the damage, and the compensation amount should be increased accordingly. When pollution affects protected areas, such as nature reserves or natural/cultural heritage sites, and causes a population decline of ≥30% in nationally protected or IUCN Red List species, or results in the loss of critical habitat functions, it shall be classified as ‘permanent damage.’ For instance, in the 130° E coral reef area, according to the 2013 ‘Marine Ecological Damage Assessment Technical Guide (Trial)’, a permanent reduction exceeding 10% in live coral cover is regarded as irreversible. Pixel-level data from mapping technologies can provide sufficient evidence to invoke the maximum statutory multiplier of 2×.

(4) Illegal gains. Illegal interests are often divided into positive interests and negative interests in comparative law [

70]. Positive interests refer to the gains obtained from infringement, while negative interests refer to the necessary expenses saved due to infringement [

71]. The higher the illegal gains, the higher the punitive damages. Specific identification includes first, direct illegal gains, that is, quantifiable economic benefits directly brought by infringement, should deduct legal production costs but not illegal costs. The second is the proportion of illegal cost, which aims to deal with the situation of low illegal cost and high gains, and only includes the expenditure directly used for infringement.

(5) Restoration measures and effects. The attitude and action taken after infringement is an important basis for judging its subjective malice [

72], and it also directly affects environmental recovery. Active, timely and effective repair behavior can reflect remorse and should be mitigated as appropriate when determining the amount of compensation; On the contrary, if you ignore or shirk, you should increase the punishment. Judging the repair measures and effects depends on two aspects: first, the start-up time of repair should be based on the date when the responsibility is determined or the time limit of administrative order. Second, the completion of remediation, which requires comprehensive quantitative (such as whether the pollutant concentration reaches the standard, whether it is stable and sustainable) and qualitative indicators (whether the ecological function is restored to the baseline). The evaluation of remediation strategies and their effectiveness should be based on the principles of prioritizing in situ remediation and ensuring equivalency for off-site remediation. If an environmental wrongdoer proactively begins remediation prior to the initiation of legal proceedings and a third-party assessment verifies that the ecological environment quality index has been restored to more than 80% of its original state, the costs incurred during the pre-litigation phase can be credited against punitive damages at a rate of 120% of the expenditure. Nevertheless, this credit may not surpass 50% of the total punitive damages awarded. If in situ remediation proves impractical, off-site remediation should be conducted within the same ecological functional zone or watershed, as verified through GIS watershed analysis. To qualify for reductions, a certification of ‘functional equivalence and net ecological benefit increase’ must be issued by an ecological expert committee and submitted to a provincial-level ecological and environmental authority. In such instances, the maximum allowable credit is also limited to 50% of the total punitive damages.

(6) Economic affordability. Punitive damages should reflect the deterrent effect but should also take into account the actual affordability of the infringer to ensure the enforceability of the judgment and the effectiveness of repair [

73]. Different infringers should be treated differently. Ordinary natural persons or small and micro enterprises have weak affordability, and excessive compensation may lead to bankruptcy. For large enterprises, a lower amount may not have a deterrent effect.

(7) Other mitigating or aggravating circumstances. Acts such as voluntarily surrendering after infringement, truthfully confessing, and actively reaching or fulfilling repair and compensation agreements can be regarded as mitigating circumstances. Refusing to cooperate with the investigation, using violence to obstruct law enforcement, taking revenge on informants or witnesses, etc., should be regarded as aggravating circumstances, and the amount of compensation should be increased accordingly to reflect severe sanctions against malicious infringement.

In addition, in view of the lack of weight distribution of current consideration factors, this study preliminarily puts forward the weight distribution scheme of various factors of punitive damages for environmental infringement (see

Table 5) for reference in judicial practice, which still needs to be further adjusted and improved in practice.

4.3. Regulating the Ownership of Punitive Damages for Environmental Tort

Establishing clear ownership guidelines for damages will incentivize private rights protection in private interest litigation while depositing civil public interest litigation damages into dedicated environmental protection funds, ensuring they are specifically allocated for environmental recovery—directly facilitating the sustainable management and conservation of ecosystems.

4.3.1. Damages in Environmental Private Interest Litigation Belong to the Victim

In environmental private interest litigation, the rationality of attributing punitive damages for environmental infringement to the infringed is that from the perspective of the unity of legal order, punitive damages are attributed to the infringed in the fields of intellectual property, food safety and consumer rights protection in China [

74]. From the functional point of view of punitive damages, punitive damages have the functions of punishment and encouragement, which can not only punish environmental torts but also encourage environmental infringers to actively defend their rights. This is because environmental torts have a wide range of infringed groups, and litigation costs are high and time-consuming. Most of the infringed people often choose to “hitchhike” and are unwilling to take the initiative to file a lawsuit. If they are not encouraged, all the infringed people will be unwilling to file a lawsuit. In environmental private interest litigation, punitive damages are attributed to the infringed, which is not only a relief for the interests of the infringed, but also a relief for the public environmental interests. In addition, attributing punitive damages to the infringer in environmental private interest litigation will not increase the burden on environmental protection agencies and organizations, nor will it affect their ability to perform environmental restoration duties. Compared with environmental civil public interest litigation, the punitive damages obtained by environmental private interest litigation are significantly low, and the expenses for environmental protection agencies and organizations to repair the ecological environment should still be mainly obtained through environmental civil public interest litigation [

75].

4.3.2. Damages in Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation Should Be Paid into Special Environmental Protection Funds

The Supreme People’s Court’s “Opinions on Strengthening Environmental Resources Adjudication” recommends establishing specialized funds for environmental public interest litigation to ensure earmarked use of punitive damages. It is inadvisable to attribute punitive damages to courts, procuratorates or the state treasury. The irrationality of belonging to the court or procuratorate lies in: first, there is no legal basis, and the current law does not stipulate that the two organs can be the subject of punitive damages. Second, the two organs do not have the ability for environmental restoration and long-term supervision. Take the restoration of American Superfund as an example, the process of environmental restoration can last for about 12 years [

76]. If the funds are managed by two agencies, it will easily lead to the extension of the implementation period and the retention of compensation in the account, making it difficult to achieve the goals of protecting the environment and maintaining public welfare [

77]. Third, as neutral arbiters, courts should not engage financially in damages, and the role of procuratorates should encompass oversight without fostering conflicting interests.

It is also unreasonable to attribute punitive damages to the state treasury, because the funds may be included in the general public budget for comprehensive fiscal expenditure and cannot be guaranteed to be dedicated to environmental restoration.

Consequently, the punitive damages in environmental civil public interest litigation should be included in the special environmental protection fund managed in the form of independent accounts, so as to realize the safe storage and effective supervision of funds and effectively use them for environmental restoration. In China, punitive damages in environmental public interest litigation accumulate on a case-by-case basis, with the establishment of dedicated funds still in preliminary stages. In practice, the extent of funding is constrained by the case volume, compensation amounts, and disparities in regional development, preventing the formation of a systematic, large-scale funding pool. However, the fund can be constructed from two dimensions of “vertical + horizontal”: vertically, in view of the wide range and great uncertainty of environmental infringement, provincial and municipal environmental protection special funds can be established. Provincial funds are suitable for cross-regional environmental cases, which helps to reduce jurisdictional disputes and improve the efficiency of fund use. Municipal funds serve the city’s environmental restoration. Horizontally, in areas where specific environmental resources are concentrated, special funds for such resources can be set up, such as a special fund for wildlife protection based on local characteristic species, in order to achieve professional management [

78]. Although the current total punitive damages awarded for environmental torts may not completely fulfill the requirements for large-scale ecological restoration across the nation, the establishment of a special fund mechanism offers an institutional assurance for the ongoing collection, efficient oversight, and specific allocation of these funds. As environmental litigation increases, compensation standards are enhanced, and public awareness of environmental issues grows, it is anticipated that the environmental special fund will progressively increase, more effectively supporting ecological restoration objectives.

Since its establishment, the fund has been integrated into the “Citizen Audit” system. By the fifth working day of each month, the custodial bank generates and encrypts the previous month’s transaction records, which are then uploaded to the provincial government’s open data portal for public access. Annually in March, the Provincial Finance Department collaborates with a third-party notary to randomly select potential citizen auditors from a list of verified residents, with specific numbers varying by province. Following a public notification period, the final selection of main and alternate auditors is confirmed. Granted the authority to inspect records, request additional data, and perform onsite checks, these auditors have their travel and accommodation expenses covered by the fund during audits. Before starting, the auditors must participate in a mandatory 1–2-day training provided by the Provincial Departments of Ecology and Environment and Finance. This training, covering transaction analysis and on-site verification techniques, ensures auditors are well-prepared. They also have access to an expert advisory pool for ongoing support. The “Citizen Auditor Operational Guide and Casebook,” produced jointly by the aforementioned departments, serves as a key resource. Centralized audits occur biannually in June and December and involve detailed inspections of key financial documents and large transactions (≥¥500,000) to ensure proper justification and compliance. During these sessions, auditors select certain projects for detailed onsite examination. Teams of at least three members each assess these sites, documenting their findings with photos and videos. If irregularities are suspected, the team prepares an “Issue Transfer Form,” submitted to the Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection and Supervision. This body then has 15 working days to issue a preliminary judgment on initiating further investigation, disseminating their findings publicly. If misuse is confirmed, the offending entity must reimburse the misused funds within 30 days, or face penalties in the form of deductions from future governmental financial transfers. Those responsible are listed on the “Dishonesty List for the Environmental Fund” for a minimum duration of three years. Comprehensive records of each audit phase, including bank statements and the final report, are preserved in encrypted electronic archives, with access durations varying by province. Redacted versions of these records are available to the public free of charge upon request with appropriate identification.

4.4. Establishing Distribution Priority Rules for Punitive Damages for Environmental Tort

From the perspective of interest rank, the private interests protected by private interest litigation should be realized before the social public interests in public interest litigation [

79]. In practice, there are three situations when private interest litigation and public interest litigation are filed at the same time for the same environmental tort. The first situation is that private interest litigation is filed before public interest litigation, and punitive damages of private interest litigation can be compensated first, and there is no distribution dispute. The second is to mention both at the same time. Plaintiffs in private interest litigation are often in a weak position in proof and professional ability, and they need to rely on the support of procuratorial organs. In order to encourage the victims to defend their rights, it is often more urgent to consider the damage of private interests (such as personal injury and property loss), and the public interests involved in public interest litigation generally do not directly endanger specific individuals [

80], so the compensation for private interests should be given priority. Article 31 of the Interpretation of Applicable Laws in Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation Cases (2020) also clearly recognizes this priority. The third is that private interest litigation is filed later than public interest litigation. At this time, the property of the infringer may not be enough to pay the compensation for private interests. We can learn from Brazil’s “two-stage” management model: in the first stage, the court decided to determine the liability for compensation and made an announcement to inform the victims to declare their claims; in the second stage, the victim applies for compensation according to the judgment. If no one claims or the amount claimed is insufficient within one year, the remaining funds can be transferred to the special fund for environmental protection [

81]. It is suggested that the proportion of deposit should be set and publicized according to the actual situation of infringement, so as to reserve the share of compensation for private interests, and at the same time set the time limit for application, and the overdue part should also be included in the special fund for environmental restoration.

By establishing the distribution order of “giving priority to compensation for private interests and using the remaining public welfare”, on the basis of giving priority to protecting people’s basic survival and health, the overdue compensation funds will eventually be transferred to the environmental protection fund, ensuring that all compensation funds can finally serve environmental restoration and providing sustainable capital circulation guarantee for the long-term stability and restoration of the ecosystem.

4.5. Establishing Offset Rules with Criminal Fines and Administrative Penalties

According to Article 187 of the Civil Code (2020) and Article 11, Paragraph 2, of the Interpretation (2022), the order of liability fulfillment should be: compensatory damages > punitive damages > criminal fines or administrative penalties. Offset provisions between punitive damages and such fines must align with these established structures, as academia has proposed one of three primary rules:

The first is the direct deduction rule, that is, already paid fines or penalties can be deducted directly from the payable punitive damages amount, adhering to the principle of “ne bis in idem” [

82].

The second is the comprehensive consideration rule, that is, judges can take previously imposed penalties into account when determining the amount of punitive damages [

83].

The third is the maximum limit rule, that is, the upper limit of all punitive property liability that the actor should bear is determined first, and if the fine or penalty does not reach the upper limit, the punitive damages will make up the difference [

84].

In practice, it is crucial to differentiate the handling of criminal fines from administrative fines, each being governed by distinct rules. The mechanism for integrating punitive damages with criminal fines should follow one of two frameworks: the “Maximum Limit + Direct Deduction” rule or the “Maximum Limit + Comprehensive Consideration” rule. Conversely, the integration with administrative fines should consistently utilize the “Maximum Limit + Direct Deduction” rule.

Specifically, when determining the offset of criminal fines, it is important to distinguish between types of legal interest infringements in legal terms. For genuine concurrency—where actions, such as illegal dumping of hazardous waste that culminates in the crime of “environmental pollution” and concurrently harms soil and groundwater quality—both criminal fines and punitive damages address the same harmed public interest, namely ecological well-being. In such cases, the “Maximum Limit + Direct Deduction” rule should be applied. For non-genuine concurrency, where disparate legal interests are impacted—for instance, illegal mining may violate “state ownership of mineral resources and the management order of mineral resources,” while a public interest lawsuit might focus on the degradation of ecological functions like landscape beauty and carbon sequestration caused by the same act. Here, different interests are infringed, so the “Maximum Limit + Direct Deduction” rule becomes inappropriate. Instead, the “Maximum Limit + Comprehensive Consideration” rule should be employed to evaluate the distinct infringements separately. Furthermore, because administrative authorities excel in enforcement efficiency, scope, and expertise, they should lead in safeguarding public interests. Hence, administrative fines often precede punitive damages in environmental cases. Punitive damages should only commence if administrative fines prove inadequate for holding the environmental offender accountable. When assessing punitive damages, any previously imposed administrative fines must be subtracted.

For the “maximum limit + direct deduction” rule to occur, three conditions must be met: actions must align with the same ecological interest, proof of payment must be provided, and the punitive damages must not exceed established limits. Specific steps include initially calculating the theoretical amount of punitive damages, deducting anticipated fines within the same upper limit. The difference is the actual amount that should be awarded, and even if it is negative, it will not be refunded unless the original criminal judgment or administrative punishment is revoked.

5. Discussion

Based on the perspective of ecological sustainability, this study systematically elucidates the deficiencies present in China’s current punitive damages regime for environmental torts, offering five structured recommendations aimed at reform: define the nature of punitive damages, standardize calculation rules related to bases, multipliers, and consideration factors, clarify ownership mechanisms within various litigation types, establish priority in distributions, and delineate offset rules between punitive damages and public law liabilities. In order to enhance the practical feasibility of the proposal, it is necessary to further analyze its policy fit, potential challenges, interdisciplinary theoretical support and scalability.

The perfect path proposed in this study is highly consistent with the ecological civilization concepts of “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” and “protecting the ecological environment with the strictest system.” For instance, the 2016 UN Environment Assembly report acknowledges China’s “Two Mountains” theory as a significant contributor to global sustainability discussions [

85]. The system of punitive damages for environmental infringement established in Article 1232 of the Civil Code (2020) is an important legal tool for the concept of ecological civilization, and the perfection of its core rule system is easy to get support from the decision-making level. The suggestions such as “standardizing the ownership” and “determining the distribution order” reflect the people-centered development thought and help to effectively protect the public’s environmental rights and interests [

86].

This study integrates diverse perspectives from law, environmental economics, ecology, and management, providing a systematic theoretical foundation. In the legal domain, it utilizes theories of public–private governance collaboration, the principle of proportionality, and corrective justice to harmonize the various legal liabilities involved. Within environmental economics, it employs frameworks concerning the internalization of negative externalities and optimal deterrence to scientifically determine the compensation amounts necessary for achieving efficiency and fairness. In ecological terms, the principles of ecosystem service value and ecological integrity are applied to emphasize the significance of interim service function loss and permanent damage in compensation calculations. Additionally, in the management arena, theories related to risk society and stakeholder engagement guide enterprises towards adopting environmentally sustainable production practices. Building on this foundation, the study effectively addresses the inherent tension between the “exemplary punishment” sought by punitive damages for environmental torts and the “legal certainty” required by the rule of law. While the former relies on discretionary flexibility and the unpredictability of sanctions to strengthen deterrence, the latter demands clear rules and predictable outcomes to stabilize expectations. To resolve this tension, the study explicitly defines punitive damages as private law claims; restricts the calculation base and sets the multiplicative limits (ranging from 1× to 2×); systematically proposes relevant consideration factors along with their corresponding weight allocation schemes; establishes distinct ownership paths for damages within public and private interest litigation; formulates distribution priority rules based on the order of litigation filing; and designs “maximum limit + offset” mechanisms for various scenarios of liability concurrence.

From a cost–benefit perspective, the compensatory frameworks suggested in this study are designed to internalize negative externalities, thereby effectively penalizing wrongdoers and deterring future infractions. Nevertheless, it is crucial during implementation to avoid inhibiting investments due to overly punitive compensation demands. To mitigate such risks, we propose a tiered compensation cap system tailored to stabilize corporate expectations. The system would vary by economic development levels across provinces. For example, total punitive damages could be limited to no more than R1% of the tortfeasor’s previous year’s operating revenue, with an additional cap set at not exceeding R2 times the net profit from that same year. In cases where a company operates at a loss or if its net profit is below a designated threshold (e.g., less than R3% of operating revenue), a singular cap of R4% of operating revenue could be enforced to lessen the burden on businesses and prevent market polarization. For industries with high environmental risks, such as the energy and chemical sectors, industry-specific adjustment factors should be considered to reflect unique industry risks while ensuring consistency across the board. Additionally, an offset mechanism for early remediation efforts should be considered. If a company completes ecological restoration before a judicial decision is finalized and this is verified by an independent assessment, the amount spent can be deducted from punitive damages at a rate of 120% pre-litigation and 100% during litigation, provided the total deduction does not surpass 50% of the awarded punitive damages. On the fiscal front, a 100% super-deduction for corporate income taxes could be allowed for expenditures on environmental protection enhancements. Moreover, a company’s record of environmental compliance should be integrated into the tax credit evaluation process, aligning with financial institutions to furnish ‘green channels’ for environmentally focused financing. This strategy preserves the punitive function of damages while enhancing their predictability and aligning them with incentive mechanisms. It strikes a balance between legal sanctions and motivations for corporate environmental advancement, aiming to safeguard the ecological environment without undermining economic vitality. Moreover, it encourages local governments to transition from traditional “GDP races” to “green development competitions,” thereby fostering a dynamic equilibrium among judicial enforcement, corporate green transformation, and sustainable local development.

Despite outlining a systematic improvement pathway, five major challenges persist in its implementation. Unified Standards and Assessment Capacity: The inconsistency in forensic assessment standards, varying competency levels across institutions, and high operational costs demand the development of scientifically sound and actionable national standards and technical guidelines. There is a need to refine assessment procedures and mechanisms for institutional access, as well as to establish expert think tanks and third-party assessment systems. Management Risks of Environmental Special Funds: These funds are plagued by inefficiency, misuse, and corruption. Legislation must specify the rules for fund allocation, management, auditing, and information disclosure, while promoting oversight by the public and social organizations. Insufficient Coordination in Implementing Offset Rules: To effectively apply offsets, it is essential to provide detailed judicial interpretations and develop inter-departmental collaboration mechanisms. These should clarify the roles and procedures for courts, procuratorates, and administrative agencies. Practical Dilemma Regarding the Recipient of Compensation from Environmental Civil Public Interest Litigation: The allocation of punitive damages from such litigation to special environmental funds—which facilitates targeted use—contrasts with the current framework where non-tax fiscal revenues are uniformly transferred to the state treasury. This necessitates coordination by the State Council with finance, taxation, and other relevant departments to define a management mechanism and legislatively establish a dual ownership structure: Thus, damages from private interest lawsuits would benefit the directly affected parties, whereas damages from public interest litigation would support environmental funds. Effectiveness in Recidivism Deterrence Needs Further Evaluation: The capacity of environmental tort punitive damage rules to deter recidivism requires more empirical assessment. Suggested measures include Establishing a case tracking database for comprehensive follow-up on punitive damage cases since 2021, including recording compliance and subsequent involvement in environmental litigation of implicated entities, particularly enterprises. Conducting interdisciplinary empirical research that integrates environmental enforcement data, corporate environmental investment data, and judicial case records for a regression analysis to scientifically determine the specific effects of punitive damages on recidivism rates. Refining research on deterrent effects by differentiating between “intentional first-time offenders” and “potential repeat offenders,” examining the influence of various factors such as the multiples of compensation and enterprise size on deterrence effectiveness. These steps are paramount to ameliorating the identified challenges and enhancing the efficacy of environmental regulations and litigation strategies.

Developing countries such as India, analogous to China, are rapidly evolving as emerging economies and encounter similar challenges in environmental governance. The Ganges River basin exemplifies these issues, grappling with severe long-term water pollution, ecological degradation, and water scarcity [

87]. Likewise, India’s environmental enforcement system confronts typical developmental challenges including fragmented regulatory structures, limited technical resources, and inefficient implementation of regulations [

88]. Within this framework, this study offers methodological and institutional insights through the proposed systematic rules for assessing punitive damages for environmental torts. Technical Level: India has developed a robust national geospatial data infrastructure and is proactive in deploying remote sensing and GIS technologies for managing natural resources. This establishes a crucial prerequisite for adopting tools akin to China’s “ecological spatial maps.” The methodologies employed in this study, using “interim service function loss” and “permanent damage” as metrics for calculating punitive damages, and further refining these assessments with spatial overlay analysis (e.g., reconciling infringement coordinates against ecological protection redlines and sensitive area layers), provide a practical technique for assessing ecological damage in multi-regional water environments such as the Ganges River basin. Rule Level: The advanced “base amount × multiplier” calculation model presented here, alongside well-defined factors and their weighted significance (e.g., subjective malice, the scale of damage, remediation effectiveness), offers India a structured adjudicative framework for complex environmental tort cases. This approach is aimed at minimizing arbitrariness in judicial discretion and enhancing the predictability and efficacy of legal outcomes. Policy Level: The concept of “exemplary sanction” highlighted in this study, illustrated by China’s pioneering application of punitive damages in environmental torts (as seen in Jiangxi Fuliang County People’s Procuratorate v. Zhejiang Hailan Chemical Group Co., Ltd. case), serves as a deterrent by penalizing prototypical cases. This approach holds significant policy relevance for a vast and enforcement-challenged nation like India, helping to address the predicament of “high enforcement costs versus low violation penalties.” Nonetheless, adapting punitive damage mechanisms across jurisdictions requires consideration of local contexts. Given India’s federated structure, where environmental legislation and enforcement primarily rest at the state level, there is a need to foster coordination mechanisms between central and state governments to ensure consistent and effective application of these rules. However, the fundamental principles of “scientifically quantifying damage and precisely determining liability” recommended in this study retain broad applicability for India and other similarly situated developing nations.

6. Conclusions

This study situates itself within the confluence of China’s “Dual Carbon” objectives and the ongoing global ecological crisis, emphasizing the principle of ecological sustainability. It seeks to address inherent challenges in China’s environmental tort punitive damages rules across five critical aspects: defining damages, methods of calculation, recipient designation, distribution hierarchy, and the interaction of these damages with public law liabilities. To enhance the judicial operability and ecological governance effectiveness of the system, this study proposes a cohesive improvement pathway. In the short term, the focus is on unifying judicial standards and reinforcing the foundation for adjudication. At the legal theory level, it clarifies the private law creditor nature of punitive damages in environmental torts, distinguishing them from public law liabilities. On the operational front, the study suggests establishing statutory bases for “interim service function loss” and “permanent damage,” with a benchmark fluctuation range of 1 to 2 times. Additionally, it calls for mandatory environmental education programs for judges and prosecutors, along with standardized protocols for the participation of environmental expert jurors in trials. In the medium term, the study emphasizes the integration of ecological space mapping for a precise assessment of ecological damage. By pioneering the use of ecological spatial mapping in determining compensation for environmental torts, this approach overlays the coordinates of infringing activities with GIS layers from eight protected areas, including nature reserves and natural cultural heritage sites. This creates verifiable spatial evidence that aids in determining “malicious intent,” “permanent damage,” and “environmental remediation measures and outcomes.” It offers judicial practice technical support and a methodological toolkit for precise, actionable decision-making. In the long term, the study focuses on establishing sustainable safeguards and collaborative governance frameworks. First, a dual-track allocation model is proposed: compensation from private interest lawsuits would go directly to the injured parties, while compensation from public interest lawsuits would be directed to an environmental protection fund. A transparent oversight mechanism, incorporating “citizen auditing” procedures, would ensure the proper use of these funds and promote public supervision. Furthermore, a priority distribution system is suggested, where private interest compensation takes precedence over public interest compensation, supplemented by creditor notice and escrow systems to safeguard fundamental human rights. The study also proposes a refined dual-track coordination mechanism, combining “maximum caps and set-off provisions,” to carefully manage the relationship between punitive damages and criminal fines or administrative penalties, based on the nature of the infringed legal interests. This framework aims to achieve a balance between punitive, restorative, and equitable aspects of both public and private law liabilities. This progressive pathway—comprising “short-term entitlement verification, mid-term technological empowerment, and long-term institutional coordination”—is firmly grounded in China’s judicial practice and integrates cross-disciplinary technological and institutional innovations. It aims to provide a comprehensive operational guide that can be directly adopted for legislative and judicial purposes. Ultimately, this approach seeks to transition the environmental tort punitive damages system from theory to practice and from principle to precision, making it a robust tool for achieving ecological sustainability goals.