Abstract

Although Sustainability Education (SE) is widely recognised as a priority across higher education, hospitality programmes often struggle to implement SE in meaningful and impactful ways. Given the hospitality sector’s resource-intensive operations and significant social footprint, SE is critical for fostering future leaders who can drive ethical, innovative, and transformative change. However, educators’ perspectives on how SE is integrated into hospitality curricula remain underexplored. This study addresses that gap by examining how educators perceive and interpret the integration of SE within Australian university programmes through a constructivist lens, recognising sustainability understanding as socially constructed through professional and institutional contexts. Twelve hospitality academics were recruited through convenience and snowball sampling and participated in semi-structured interviews. The data were thematically analysed using NVivo 14. Findings reveal four barriers, institutional constraints, curriculum overload with weak assessment frameworks, cultural resistance, and fragile industry–academic linkages. Leadership commitment and educator training emerged as critical enablers for advancing meaningful SE. The study concludes that hospitality curricula require stronger pedagogical innovation to move beyond tokenistic approaches. Embedding sustainability as a graduate attribute, supported by clear policies, measurable indicators, and industry–academic partnerships, is essential for systemic transformation aligned with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

1. Introduction

The hospitality industry is both resource-intensive and socially influential, contributing to global sustainability challenges such as environmental degradation, excessive energy and water consumption, food waste, and labour inequities [1,2,3]. Given this extensive footprint, the sector has both the responsibility and the capacity to drive systemic change [4]. As graduates enter such complex environments, sustainability education (SE) becomes vital to preparing leaders capable of addressing environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability [5].

Within higher education, the urgency of embedding SE is reinforced by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), which call for equipping learners with competencies for sustainable development [4,5]. Hospitality education occupies a unique position, as it connects the operational realities of service industries with broader societal systems, yet often struggles to balance academic ideals with market pressures [5].

Despite growing awareness, sustainability implementation in hospitality curricula remains fragmented and tokenistic [6,7,8]. Berjozkina and Melanthiou (2021) [9] describe tokenism in SE as symbolic or compliance-driven gestures, such as isolated lectures or recycling campaigns, that signal environmental awareness without transforming underlying pedagogical structures. Prior research highlights barriers such as curriculum overload, limited faculty training, and weak industry collaboration [7,8,9,10].

There is a significant lack of qualitative evidence that captures the lived experiences of educators and their insights regarding the implementation of sustainability principles in classroom practices. This gap is especially evident within the Australian context, which is renowned worldwide for its excellence in hospitality education. Despite this reputation, there has been limited investigation into the systemic barriers that hinder, as well as the enablers that promote, the effective integration of sustainability education in these programmes. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies that can enhance the inclusion of sustainability concepts in teaching and learning frameworks.

This paper is derived from a broader doctoral study that explored the integration of sustainability education (SE) within Australian hospitality management programmes [11]. The original project employed a two-phase qualitative design: an initial document analysis of hospitality curricula conducted between 2020 and 2021, followed by semi-structured interviews with hospitality educators. The current paper focuses solely on the interview phase to provide a focused, interpretive account of educators’ perceptions, experiences, and the institutional factors shaping SE integration. The earlier document analysis informed the interview design and interpretation but is not presented here, as curriculum content has since evolved, and the present analysis concentrates on educators’ lived experiences.

This study is based on three complementary theoretical perspectives that explain how educators develop, internalise, and apply sustainability values in their professional practice: constructivism, transformative learning, and organisational learning. The research aims to explore how sustainability education (SE) is conceptualised, implemented, and supported within Australian hospitality management programmes. Specifically, it seeks to identify the institutional, curricular, and cultural factors that influence the integration of SE and to highlight strategies that could promote systemic change.

The inquiry is guided by three questions:

- (1)

- How do hospitality educators conceptualise and implement SE in their curricula?

- (2)

- What institutional, cultural, and industry factors hinder or enable integration?

- (3)

- How can these insights inform sustainable curriculum transformation and policy development?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Global Trends in Sustainability Education in Hospitality

Sustainability education (SE) has rapidly become central to higher-education agendas worldwide, reflecting the growing urgency to prepare graduates with the competencies needed to navigate complex environmental, social, and economic systems. In hospitality, an industry marked by resource-intensive operations and extensive stakeholder networks, scholars have noted that the translation of sustainability principles into coherent curricula remains inconsistent.

Piramanayagam, Mallya, and Payini [12] conducted a comprehensive bibliometric and systematic review of more than 400 hospitality and tourism studies published between 2010 and 2023. Their analysis, based on Scopus and Web of Science data, revealed that research on sustainability education (SE) remains fragmented, geographically uneven, and conceptually underdeveloped. Most publications originated from developed economies, particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, with minimal representation from developing regions, highlighting a persistent geographic imbalance in sustainability education scholarship. The authors further noted that curriculum design and pedagogy represented only a small share of studies, while most focused on student attitudes or corporate social-responsibility initiatives.

This global review provides a critical foundation for the present study. It highlights the persistent conceptual fragmentation and regional imbalance in the field, underscoring the need for context-specific, educator-centred investigations. Building on this base, recent scholarship reinforces that challenge. Zhang and Tavitiyaman [6] found that both students and practitioners in Hong Kong recognised sustainability’s importance but treated it as an optional rather than core competency. Zeng et al. [8] noted that most institutions lack context-sensitive assessment frameworks, while Blanco-Moreno et al. [13] reported that pedagogical innovation lags behind policy discourse. Similarly, Liu et al. [10] demonstrated that learner-centred, experiential approaches, such as farm-to-table projects and carbon-footprint simulations, can enhance engagement but remain isolated cases. Fernández-Villarán et al. [5] showed that Spanish tourism curricula align rhetorically with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) yet fail to translate them into measurable learning outcomes, and Maguire et al. [7] found that Irish programmes face persistent faculty training gaps and weak institutional frameworks.

Taken together, these studies illustrate a global paradox: the hospitality sector acknowledges the ethical and economic imperatives of sustainability, yet higher-education programmes continue to integrate SE inconsistently and often superficially. This pattern of rhetorical commitment but limited transformation underscores the need for qualitative, context-driven analyses, such as the present study, that explore how educators themselves interpret and enact sustainability within their institutional realities.

Building on these global insights, the following section examines the recurring barriers and enablers identified in recent scholarship, providing a conceptual foundation for analysing the Australian context.

2.2. Key Barriers to Meaningful SE Integration

A recurring finding across recent scholarship is that sustainability education (SE) in hospitality remains hindered by entrenched structural and institutional barriers. The most pervasive of these is curriculum overload, in which the already dense content of hospitality management programmes competes with the addition of new sustainability-related modules. As Piramanayagam et al. (2023) [12] observed, most universities face intense pressure to deliver discipline-specific technical skills alongside employability outcomes, leaving limited room for integrative, reflective approaches to sustainability. The result is often a fragmented inclusion of sustainability topics, confined to elective courses, or treated as isolated “add-ons” rather than as cross-disciplinary principles embedded throughout the curriculum.

Faculty training and institutional support form the second major obstacle. Zeng et al. (2024) [8] found that while educators increasingly recognise the relevance of sustainability competencies, many lack the time, resources, and professional development needed to adapt their pedagogical practice. Similarly, Kang et al. (2024) [14] highlight that faculty perceive insufficient time, resources and knowledge as key barriers to integrating sustainability across curricula. Muhonen et al. (2025) [15] found that higher education institutions often lack coherent human resource strategies for developing sustainability competencies. Similarly, recent empowerment studies by Ankareddy et al. (2024) [16] emphasise the need for structured faculty development frameworks and sustained institutional support systems.

A third barrier concerns industry–academic collaboration, which is vital for ensuring that sustainability learning remains authentic and practice-driven. However, evidence suggests that such partnerships are frequently weak or narrowly focused. In many regions, including parts of Asia and Europe, collaboration tends to emphasise operational efficiency (e.g., waste reduction, energy use) rather than social or economic justice dimensions [13,14,15,16]. As Berjozkina and Melanthiou (2021) [9] note, such surface-level initiatives exemplify “tokenism,” where sustainability is expressed through symbolic or compliance-driven gestures rather than transformative practice. This pattern persists in higher education, where Woldegiorgis and Turner (2023) [17] observe that institutional partnerships often prioritise visibility over genuine curricular integration, signalling awareness without systemic change.

The combined effect of curriculum congestion, limited educator capacity, and superficial industry engagement is that many hospitality programmes adopt sustainability in name but not in practice. Hassan et al. (2025) [18] found that seniority-based hierarchies within hospitality faculties often inhibit curricular innovation by privileging tenure over recent industry experience; institutions that foster equitable academic–industry exchange demonstrate greater capacity for embedding sustainability. Recent reviews further reveal that many institutions publicise sustainability as a brand value while failing to embed it within measurable learning outcomes or assessment frameworks [19,20]. This pattern of rhetorical commitment without systemic transformation underscores the need for qualitative inquiry, such as the present study, that examines how educators navigate, interpret, and attempt to overcome these enduring structural barriers.

Understanding why these barriers persist and how educators attempt to navigate them requires examining the national and institutional contexts in which hospitality programmes operate. While global studies have identified common structural and cultural constraints, the specific dynamics within Australia’s higher education sector remain underexplored. To address this omission, the following section situates the discussion within the Australian context, outlining the distinctive policy environment, institutional conditions, and research gaps that justify the present study.

2.3. The Australian Context and Research Gap

Australia is widely recognised for its robust higher education system and globally ranked hospitality programmes, yet sustainability education (SE) integration within this sector remains uneven and under-examined. Despite national policy initiatives, such as the National Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development [21] and Australian Universities Accord Report [22], and National Statement of Commitment to Transform Education [23] that call for embedding sustainability competencies across disciplines, research reveals a persistent implementation gap between institutional rhetoric and pedagogical reality. Faculty-led transitions toward sustainability education require more than curriculum changes; they depend on institutional strategies that actively empower and resource academics, including clear action plans, training pathways, and sustained organisational commitment. Segalàs and Tejedor [24] argue that there is no universal model for embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), but progress is most effective when universities align faculty attitudes, incentives, and professional development with their broader sustainability vision. Studies of Australian universities indicate that sustainability is often framed as an aspirational brand value rather than an assessed learning outcome, with sustainability topics commonly appearing in elective or introductory units rather than within capstone or assessment frameworks [25,26].

While sustainability has become a visible policy objective across Australian universities, few institutions possess clear accountability structures to measure educational impact. Australian universities increasingly publicise sustainability commitments, yet reporting and measurement remain patchy, with many providers lacking fit-for-purpose frameworks for tracking educational outcomes; national reviews likewise call for clearer performance metrics and accountability mechanisms for curriculum impact [25]. This imbalance has created a policy–practice divide: sustainability is endorsed at the strategic level but inadequately operationalised at the programme level.

Within hospitality education specifically, empirical evidence remains limited. Wang et al. (2024) [27] examined how the Australian Tourism, Hospitality, and Events (TH&E) Curriculum and Assessment Quality Framework (CAQF) is perceived by educators in Taiwan. Their findings suggest that while Australian curricula consistently reference sustainability within programme aims, graduate attributes, and accreditation language, the translation of these commitments into pedagogical depth and assessment design is uneven. Participants viewed the Australian framework as conceptually strong but operationally weak. A system that articulates sustainability values without embedding them through measurable learning outcomes or authentic, practice-based assessments.

Crucially, the study highlights a perceptual gap: Australian institutions are seen to “perform” sustainability rhetorically, signalling global leadership, yet lack transparent mechanisms to evaluate how sustainability is actually taught or assessed within core hospitality units. This external critique reinforces findings from national studies [11,25,26] that the alignment between curriculum intent and teaching practice remains superficial. Together, these studies point to a need for educator-centred qualitative inquiry, like the present paper, that explores how such frameworks are enacted, negotiated, or resisted in everyday academic practice. These findings align with global analyses by [9,12,14] who report similar patterns of superficial adoption in hospitality programmes internationally.

Broader Australian higher-education studies reinforce these concerns. The Education for Sustainability and the Australian Curriculum Project (AESA, 2014) [28] found that while awareness of sustainability education principles was high, institutional follow-through on assessment and faculty training was inconsistent. Taken together, these studies reveal that the Australian experience mirrors a broader international paradox: while sustainability is championed as an institutional priority, its curricular implementation often remains symbolic or tokenistic. The lack of qualitative, educator-centred research compounds this gap. Most existing studies either quantify policy mentions or survey student attitudes, neglecting the nuanced, lived experiences of educators who mediate between institutional strategy and classroom reality. As Aljaffal (2023) [11] notes, understanding how educators interpret, negotiate, and enact sustainability within hospitality curricula is critical to bridging the rhetoric–practice divide.

Accordingly, the present study responds to this void by providing an interpretive, educator-centred examination of SE integration across Australian hospitality programmes. It investigates how institutional priorities, cultural expectations, and industry partnerships shape educators’ capacity to embed sustainability meaningfully. In doing so, it contributes to both national and global scholarship by illustrating how sustainability education can evolve from symbolic compliance toward systemic transformation within a key vocational discipline.

Addressing this persistent rhetoric–practice divide requires understanding how educators interpret, negotiate, and enact sustainability under institutional constraints. To examine these dynamics, the study adopts constructivist, transformative, and organisational learning perspectives, detailed in the following section.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

This study is guided by three interrelated theoretical perspectives, constructivism, transformative learning, and organisational learning, which together provide a robust lens for interpreting how educators conceptualise and enact SE in hospitality programmes.

Constructivism, first articulated by Vygotsky [29] views knowledge as a socially constructed process shaped by interaction, culture, and experience. Learning occurs first between individuals and is later internalised through reflection and dialogue, a process known as social constructivism. Collaboration, language, and engagement with more knowledgeable others form the basis through which learners build new understanding from prior knowledge [30]. In higher education, constructivist pedagogy emphasises student-centred learning and active inquiry, both essential for SE where learners must interpret and navigate complex socio-ecological systems [31,32]. In hospitality education, this requires educators to design learning experiences that engage students in authentic sustainability challenges, such as resource management, ethical consumption, or social equity, rather than relying on passive content delivery [33,34]. Adopting this lens positions educators not as transmitters of sustainability facts but as co-creators of meaning within institutional and cultural contexts.

Transformative learning theory [35,36] centres on how individuals revise their frames of reference through critical reflection, leading to a shift in meaning-perspectives. Recent work emphasises its applicability to sustainability education: emotions, moral disequilibrium, and critical reflection become triggers for change [37]. Trevisan et al. (2024) [38] found that transformative and organisational learning combined provide a useful framework for institutions seeking sustainability whole-institution. Frank et al. (2024) [39] show that without addressing cognitive biases, sustainability education risks remaining superficial, reinforcing comfort zones rather than challenging them. This is why Transformative Learning is so essential: it provides a theoretical mechanism for moving learners (and educators) beyond “awareness” to “actionable change in worldview.” Their review thus supports the idea that transformative learning must be consciously facilitated in SE through reflective dialogue, discomfort, and experiential engagement, not just information transmission. Within the context of hospitality education, this theory helps explain how committed educators may move beyond tokenistic gestures (e.g., isolated sustainability modules) toward deeper pedagogical innovation when their assumptions about hospitality, industry and sustainability are challenged. Thus, this lens supports exploration of not just what is taught, but how and why educators might shift their approach in response to institutional, cultural and industry-linked pressures.

Organisational Learning Theory [40] provides the institutional counterpart to these individual-level transformations. Originating in the work of Argyris and Schön (1978) [40], this theory posits that organisations learn and adapt through feedback, reflection, and the modification of shared mental models. Within the higher-education context, it has become a foundational lens for analysing how universities integrate sustainability across curriculum, governance, and operations [41,42]. de Campos Junges et al. (2024) [41] conceptualise universities as learning organisations that must internalise sustainability principles throughout institutional structures. Yet, most remain at the single-loop learning stage, making procedural improvements without challenging underlying assumptions about knowledge or success. In contrast, ElBawab (2024) [42] empirically demonstrates that universities with strong organisational-learning cultures, characterised by leadership commitment, staff collaboration, and reflective evaluation, achieve higher sustainable performance outcomes. Within hospitality education, this perspective highlights how leadership priorities, institutional resourcing, and industry partnerships shape educators’ capacity to embed SE meaningfully. Organisational learning thus situates individual educator agency within the larger ecosystem of institutional adaptation.

By integrating these three frameworks, this study addresses SE at multiple scales: constructivism captures how educators and learners co-create meaning; transformative learning explains how critical reflection drives changes in pedagogical worldview; and organisational learning reveals how institutional systems either enable or constrain sustained change. This composite theoretical framework aligns directly with the study’s research questions, which explore how educators conceptualise and enact SE (constructivist), what factors hinder or enable integration (transformative and organisational), and how insights inform systemic transformation (organisational). These perspectives collectively inform the methodological design, shaping both the interview structure and thematic analysis by guiding attention to meaning-making, reflection, and institutional context.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study adopted a qualitative, interpretivist research design [43] guided by the principles of constructivism, transformative learning, and organisational learning. Within this paradigm, knowledge is understood as co-constructed through human experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than discovered as objective truth. Such a perspective is particularly suited to examining how educators conceptualise, enact, and negotiate sustainability education (SE) within complex institutional and cultural contexts.

According to Creswell and Poth (2023) [43], qualitative inquiry enables researchers to explore participants’ lived experiences and interpret the meanings they assign to social phenomena. This interpretivist approach privileges depth over breadth, seeking to illuminate the why and how of human behaviour rather than measure its frequency. The research therefore focused on uncovering educators’ internal reasoning, emotional labour, and contextual decision-making as they navigated competing academic and institutional demands related to sustainability. Tracy (2024) [44] emphasises that interpretivist designs are especially powerful when researchers aim to examine the values-based and ethical dimensions of professional practice, as is the case with sustainability teaching. The criteria for qualitative rigour outlined by Tracy (2024) [44] are sincerity, credibility, resonance, and significant contribution, which guided the study’s methodological decisions.

Thus, the interpretivist paradigm underpinning this research reflects both its theoretical and ethical commitments: to engage participants as knowledge co-creators, to prioritise context over generalisation, and to illuminate the interplay between personal belief systems, pedagogical practice, and institutional culture. The design is inherently exploratory, aiming not to generalise but to generate situated, actionable insights that contribute to both educational practice and scholarly understanding of sustainability integration in hospitality higher education.

The research design was implemented in two sequential phases: an initial document analysis of hospitality curricula followed by semi-structured interviews with hospitality academics. The present paper reports findings from the interview phase only. The decision to focus exclusively on interviews was deliberate. As the purpose of this study was to capture educators lived experiences, interpretive insights, and reflections on sustainability education, interviews provided the most appropriate means of generating rich, contextualised narratives. This qualitative emphasis aligns with the study’s constructivist and transformative learning foundations, privileging depth of understanding over breadth of measurement. The earlier document analysis informed the interview guide and interpretation but was not repeated to avoid redundancy and to maintain analytical focus on participants’ experiential perspectives.

3.2. Participants and Sampling

Twelve hospitality academics from Australian universities participated in this study. Participants were selected through purposive and snowball sampling approaches, which is well-suited to qualitative research seeking rich, contextualised understanding from specialised professional populations.

Purposive sampling was used to intentionally recruit information-rich participants, academics with substantial experience in teaching, curriculum design, or research within hospitality higher education. This strategy enables researchers to select participants and sites that can purposefully inform an understanding of the central phenomenon [44]. As Patton (2015) [45] notes, purposive sampling maximises depth and relevance, ensuring that participants possess the insight necessary to illuminate the research questions rather than represent a statistical population.

Snowball sampling was subsequently employed to broaden participation through professional referrals, a well-established method for accessing interconnected academic networks [46]. Because hospitality academics often operate within tightly knit disciplinary and institutional circles, peer recommendations were instrumental in identifying colleagues with diverse teaching and research perspectives across Australia.

Initial recruitment occurred through professional connections established at the Council for Australasian Tourism and Hospitality Education (CAUTHE) [47] Conference and on LinkedIn, followed by participant referrals. This approach facilitated access to educators from a range of university types (research-intensive, regional, and teaching-focused), academic ranks, and disciplinary subfields within hospitality management.

Together, purposive and snowball sampling enhanced the credibility and transferability of findings by assembling a theoretically relevant and experientially diverse participant group, an approach consistent with interpretivist research principles that privilege depth, contextual insight, and meaning over representativeness [44,45,46]. The final sample represented educators across diverse institutions (public and private), career stages (early, mid, and senior-level academics), and programme roles (course coordinators, lecturers, and heads of discipline), thereby strengthening transferability across comparable contexts.

The sample size (n = 12) was determined according to the principle of thematic saturation, defined as the point at which no new codes or themes emerge from successive interviews [48,49]. Empirical research shows that 12–15 interviews are typically sufficient to capture meaningful thematic patterns in relatively homogeneous participant groups [49]. Vasileiou et al. (2018) [50] emphasise that sample sufficiency in qualitative research depends on the study’s purpose, the quality of dialogue, and the depth of interpretation rather than on fixed numerical benchmarks. In their systematic review of more than 200 interview-based studies, they observed that thematic sufficiency is commonly achieved with 6–20 participants, particularly when participants share a coherent professional background. Within this study, the participant cohort, hospitality academics with specialised teaching and curriculum expertise, constitutes a relatively homogeneous yet experientially diverse group. This aligns with Vasileiou et al.’s conclusion [50] that smaller, purposively selected samples can yield rich, credible, and analytically robust insights once saturation is reached.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants, highlighting their diverse academic and industry backgrounds, qualifications, and roles across multiple Australian institutions.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 12).

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews designed to capture educators’ perceptions, experiences, and reflections on sustainability education (SE) integration. Interviews were conducted between March and July 2021, either via Zoom or in person, depending on participant preference. Each session lasted approximately 60–90 min and followed a flexible, open-ended guide that encouraged participants to elaborate on how they conceptualised, enacted, and navigated SE in their teaching and curriculum design. This approach balanced consistency across interviews with the flexibility to pursue emergent ideas, consistent with Creswell and Poth’s (2023) [43] emphasis on iterative, meaning-oriented inquiry and Tracy’s (2024) [44] criteria of “sincerity” and “rich rigor” in qualitative research.

The interview guide comprised three main sections, each designed to elicit rich, reflective responses. Section 1 captured demographic and professional background information to contextualise each participant’s experience, including academic role, qualifications, and years of teaching in hospitality higher education. Section 2 explored the extent and nature of SE integration, focusing on curriculum design, learning activities, assessment approaches, and institutional influences on pedagogy. Section 3 examined perceived challenges and enablers to embedding SE, inviting reflection on leadership, culture, and examples of effective or innovative practice.

Probing questions encouraged elaboration and critical reflection, allowing educators to articulate both systemic barriers and personal pedagogical strategies. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim with participant consent. Field notes were taken immediately after each session to capture contextual observations and researcher reflections. Participants received their transcripts for member checking, and minor clarifications were incorporated where relevant.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol No. H13612). All participants provided informed consent and were assured of confidentiality, anonymity, and their right to withdraw at any time. Identifying details have been removed or generalised to protect participant privacy.

The data were then prepared for systematic analysis, as outlined in the following section.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2021) [51] six-phase approach to thematic analysis, which provides a flexible yet systematic framework for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns of meaning within qualitative data. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 14 for organisation and coding. Initial inductive coding was conducted line by line to capture salient concepts and recurring ideas directly from the data. This inductive orientation allowed codes to emerge naturally from participants’ narratives rather than being pre-imposed by existing theoretical constructs, ensuring that the analysis remained grounded in participants lived experiences. Through iterative comparison and refinement, these preliminary codes were grouped into higher-order categories that reflected systemic barriers, pedagogical strategies, institutional enablers, and educators’ evolving conceptions of sustainability. An Excel matrix was used to cross-compare patterns across all twelve interviews, supporting both horizontal (across cases) and vertical (within case) thematic consistency.

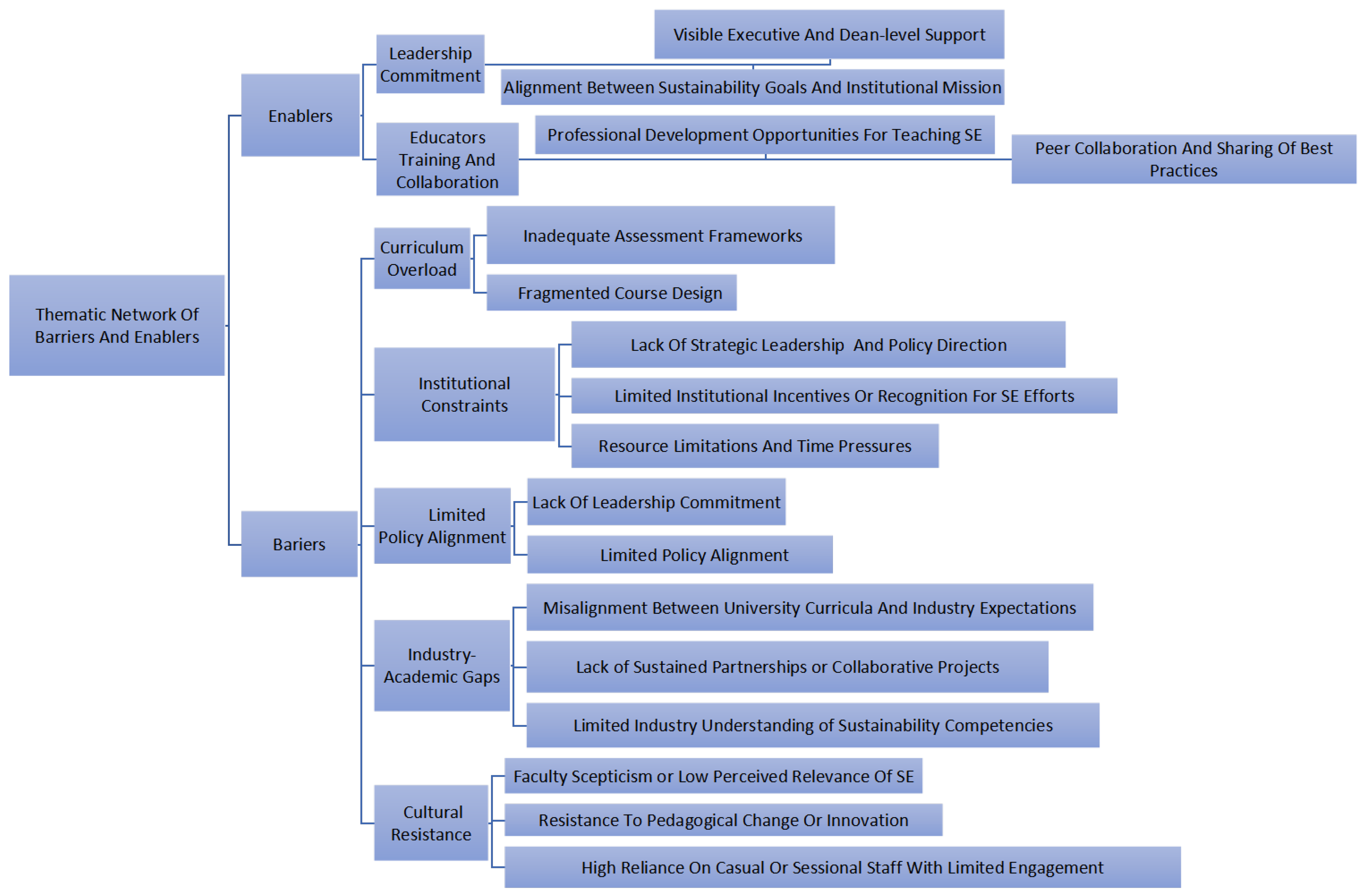

To illustrate the relationships identified through thematic coding, Figure 1 presents the Thematic Network of Barriers and Enablers generated in NVivo 14. The diagram visualises how participants’ narratives clustered around two overarching domains, Barriers (institutional constraints, curriculum overload, cultural resistance, and weak industry–academic linkages) and Enablers (leadership commitment and educator training and collaboration). Each domain is further divided into subthemes that represent the structural, cultural, and pedagogical factors shaping sustainability education within Australian hospitality programmes.

Figure 1.

Thematic Network of Barriers and Enablers.

The interpretive orientation of this study meant that coding was not limited to surface-level description; instead, it sought to uncover underlying assumptions and meaning structures consistent with the study’s constructivist and transformative learning perspectives. Themes were reviewed and redefined through repeated engagement with the data to ensure coherence and theoretical alignment.

To enhance trustworthiness, several validation strategies were implemented in line with Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) [52] criteria and subsequent methodological refinements. Credibility was strengthened through member checking with five participants, who reviewed summary interpretations for accuracy and resonance. Dependability and confirmability were ensured through peer debriefing with academic supervisors, who provided critical feedback on coding consistency and theme construction. Transferability was supported by providing detailed contextual descriptions of participants and institutional settings, allowing readers to assess the applicability of findings to similar contexts.

Ethical and data management standards were rigorously maintained. The anonymised transcripts and coding framework are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical restrictions, raw transcripts cannot be publicly shared.

In addition, document analysis was undertaken to triangulate the interview data. Publicly available curriculum documents, unit outlines, and programme handbooks, sourced from university websites and participant-provided materials, were examined for sustainability-related content, learning outcomes, and assessment strategies. This triangulation strengthened the interpretive depth of the findings and ensured analytic credibility.

4. Findings and Analysis

The thematic analysis of twelve in-depth, semi-structured interviews revealed a complex interplay of four overarching barriers and one cluster of enabling strategies that collectively shape how sustainability education (SE) is understood, prioritised, and enacted within Australian hospitality programmes. These emergent themes—institutional constraints, curricular challenges, cultural and workforce dynamics, industry–academic partnerships, and enabling strategies—capture both the systemic impediments and the sites of innovation through which educators negotiate sustainability in their professional practice. The findings reflect not merely descriptive categories but interlocking dimensions of a larger organisational ecosystem, where policy ambitions, pedagogical realities, and industry expectations often collide.

The analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2021) [51] reflexive thematic approach, enabling the identification of patterned meanings across the dataset while remaining sensitive to individual context and voice. Themes were derived inductively through repeated coding cycles, iterative comparison within and across cases, and continuous theoretical reflection guided by the study’s constructivist and transformative learning frameworks. This process moved beyond surface-level description toward interpretive depth, illuminating how educators co-construct and sometimes contest the meanings of sustainability under varying institutional pressures.

To visually synthesise these interconnections, Figure 1 presents the NVivo-generated Thematic Network of Barriers and Enablers, which depicts the hierarchical relationships between codes, subthemes, and overarching categories. Table 2 complements this visualisation by providing representative quotations that illustrate the nuances of each theme, demonstrating the diversity of educator perspectives and the analytical reasoning that underpins the thematic structure.

Table 2.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes.

4.1. Institutional Constraints

Educators consistently described institutional constraints as the most significant barrier to authentic sustainability integration. Sustainability, they argued, often appeared in mission statements yet failed to materialise in resource allocation or leadership priorities.

“They talk about sustainability in every strategy,” noted one senior lecturer, “but when we ask for release time to redesign a unit, there’s suddenly no budget” (Academic 1). Others described this pattern as symbolic compliance, aligning with Berjozkina and Melanthiou’s (2021) [9] concept of tokenism, in which public declarations of sustainability are separate from pedagogical transformation.

The proliferation of casual academic contracts further entrenched this disconnection. As one participant explained, “Casuals like me don’t have the authority or even the time to make changes” (Academic 4). From an organisational learning perspective, this reveals a single-loop learning process: institutions adjust language and policy without questioning underlying structures that constrain innovation. Collectively, these comments expose a system where leadership rhetoric eclipses the material support required for curriculum renewal.

4.2. Curricular Challenges

Participants repeatedly characterised the hospitality curriculum as overcrowded and fragmented. “We’ve already got overloaded units. To properly integrate sustainability, something else has to give, and that rarely happens” (Academic 8). The pressure to maintain technical and operational content, such as cost control, service quality, and event logistics, left minimal space for new competencies. The result was superficial coverage, or what one educator labelled “greenwashing tick-box teaching” (Academic 10).

However, dissenting voices offered glimpses of progress. “In our food-production subject, students calculate carbon footprints for menus,” reported Academic 3. “It’s practical, they see waste, not just talk about it.” These contrasting accounts demonstrate the coexistence of tokenistic gestures and transformative experimentation within the same disciplinary space.

Viewed through a constructivist lens, educators are negotiating meaning within conflicting institutional narratives, some reproducing compliance-based practices, others reconstructing pedagogy through reflection and dialogue. Without measurable assessment frameworks, sustainability risks remain a thematic decoration rather than an integrated competency.

4.3. Cultural and Workforce Dynamics

Cultural attitudes emerged as a subtle yet pervasive barrier. Several participants noted that colleagues treated sustainability as peripheral or politically charged. “Some still think it’s activism, not education” observed Academic 7. This cultural hesitation was mirrored among students, many of whom prioritised employability over environmental or ethical concerns: “They ask, ‘how does this get me a job?’” (Academic 1).

The casualisation of teaching compounded this problem, limiting opportunities for sustained mentorship and curriculum innovation. As Academic 11 explained, “You’re hired to deliver content, not redesign it.” From a transformative learning perspective, these findings suggest that both educators and students occupy pre-reflective stages of awareness; without institutional triggers for critical reflection, sustainability remains cognitively acknowledged but behaviourally dormant.

Cultural resistance, therefore, operates as an adaptive defence mechanism, protecting existing professional identities against the discomfort of paradigm change. Overcoming it requires safe spaces for dialogue and reward systems that recognise sustainability-oriented innovation.

4.4 Industry–Academic Partnerships

The interviews revealed a recurring disconnect between educational ambition and industry demand. Employers rarely requested sustainability-trained graduates, which discouraged deeper integration at the curriculum level. “If hotels aren’t asking for it, universities won’t prioritise it” said Academic 1. Another added, “Our partners care more about cost efficiency than carbon efficiency” (Academic 6).

Nevertheless, educators identified emerging bridges between academia and industry. Guest speakers from sustainable hotel chains, industry challenges on waste minimisation, and student-led audits were cited as effective tools for applied learning. One lecturer (Academic 5), who possessed extensive industry experience and well-established professional networks, described personally leveraging these connections to enrich student learning. “I bring in someone from hotels to talk about circular practices; it flips the switch for students”, he explained. This initiative exemplifies individual agency in the absence of formal institutional frameworks, demonstrating how educators with professional credibility can mobilise their networks to embed authentic industry perspectives within the classroom. These collaborations embody double-loop learning, where engagement with external stakeholders provokes reflection on internal teaching norms and catalyses incremental curricular transformation. Yet such partnerships remain sporadic. Without systemic frameworks linking accreditation bodies and industry to sustainability metrics, these initiatives risk remaining isolated experiments rather than structural reform.

4.5. Enablers and Strategies for Change

Despite challenging constraints, educators demonstrated creativity and persistence in identifying strategies that could move hospitality education beyond rhetorical engagement with sustainability. Their insights reveal that systemic change, while institutionally fragile, can be cultivated from within through informed pedagogy, leadership alignment, and learner empowerment. Four key enablers consistently emerged from the interviews.

- 1.

- Embedding sustainability across core units

Participants repeatedly emphasised that sustainability must move from the margins of elective offerings into the mainstream of programme design. “If students only hear about sustainability in an elective, they’ll see it as optional,” explained Academic 4. Embedding sustainability as a graduate attribute rather than an add-on ensures continuity and reinforces its relevance across disciplinary boundaries. Educators argued that true integration requires aligning sustainability competencies with unit learning outcomes and assessment rubrics, enabling students to encounter these principles not once, but repeatedly through their learning journey. This systemic embedding represents a form of organisational learning, where curriculum structures evolve to reflect institutional values rather than individual enthusiasm alone.

- 2.

- Experiential and problem-based learning to bridge theory and practice

Many educators described experiential and project-based activities as transformative vehicles for understanding. “When they audit the kitchen’s waste stream, sustainability suddenly becomes real”, reflected Academic 7. Others incorporated hotel sustainability reports, energy audits, and food-waste challenges as authentic assessment tasks. These activities foster constructivist learning, where students build understanding through doing, reflecting, and engaging with tangible sustainability dilemmas. Such approaches dissolve the boundary between classroom and industry reality, fostering action competence, the ability to translate sustainability ideals into operational practice. Academic 3 elaborated that these experiences often sparked “aha” moments, revealing how sustainability intersects with cost efficiency, quality control, and ethics simultaneously.

- 3.

- Leadership commitment and institutional alignment

While individual champions can ignite change, participants stressed that institutional structures must sustain it. “It’s not enough for a few champions to care; sustainability has to be in KPIs”, asserted Academic 2. Educators described the need for top-down leadership commitment, policies that embed sustainability into teaching, key performance indicators, curriculum review processes, and academic promotion frameworks. Without this alignment, initiatives risk fading when key individuals depart. From an organisational learning perspective, this stage marks the shift from isolated innovation to institutional memory: sustainability becomes encoded within governance systems rather than dependent on personality or goodwill. Several participants called for clear accountability mechanisms, faculty-wide workshops, and funding allocations to translate rhetorical mission statements into measurable outcomes.

- 4.

- Harnessing student engagement as a catalyst for change

Finally, participants highlighted the potential of student voices as powerful levers of transformation. “When students push for change, it creates momentum that institutions cannot ignore”, emphasised Academic 10. Educators observed that student activism—manifested through green clubs, project ideas, or sustainability-focused feedback—often stimulates administrative responsiveness. This reflects a transformative learning dynamic, where the enthusiasm and moral conviction of learners’ challenge educators and institutions to re-examine their assumptions. By positioning students as co-creators rather than passive recipients, sustainability education gains authenticity and moral urgency. Academic 8 noted, “The best ideas come from students, they’re living sustainability in ways we’re still learning to teach.”

Together, these narratives demonstrate that meaningful change in sustainability education does not depend solely on policy reform but on distributed agency, the collective actions of educators and students who co-construct meaning within institutional constraints. Through a constructivist–transformative synthesis, educators operate simultaneously as learners and change agents, experimenting within imperfect systems to model the very adaptability that sustainability demands.

4.6. Summary

The findings collectively reveal that the transition from rhetorical to authentic sustainability requires alignment across three interdependent levels: pedagogical innovation (curriculum design, learning activities, and assessment frameworks), organisational governance (leadership commitment, accountability systems, and policy reinforcement), and external collaboration (industry and community partnerships). Where these dimensions converge, sustainability ceases to be a symbolic gesture and becomes a living, iterative practice embedded within the DNA of hospitality education.

Overall, the analysis paints a nuanced portrait of sustainability integration within Australian hospitality programmes. Institutional branding without genuine investment, overloaded curricula, cultural rigidity, and fragile industry linkages constitute interlocking barriers that perpetuate superficial engagement. Yet within these same structures, committed educators and motivated students are cultivating transformative practices that challenge institutional complacency. The persistent tension between tokenism and authentic integration underscores the need for universities to evolve from symbolic compliance toward systemic, measurable change; a process explored in greater depth in the following Discussion Section.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of research on sustainability education (SE) in hospitality by revealing how educators navigate the persistent gap between institutional rhetoric and pedagogical reality. The findings illustrate a system shaped by competing forces: structural rigidity, cultural resistance, and individual agency. Within this interplay, educators act as both constrained participants and catalysts of transformation. By interpreting these dynamics through the lenses of constructivist, transformative, and organisational learning theories, this section theorises why barriers endure and how meaningful change may emerge despite them.

The barriers identified in this study, limited resources, curriculum overload, casualised labour, and weak industry linkages, mirror global patterns reported in sustainability education research [4,12,16,20]. Yet their persistence cannot be attributed solely to administrative oversight. From an organisational learning perspective, these obstacles reflect single-loop learning [40], where universities adjust policies and language without questioning the deeper structures that reproduce inefficiency. Sustainability thus becomes rhetorically embedded but operationally marginal.

Institutional lock-in further explains why reform efforts often stall. Bureaucratic cultures tend to reward compliance over creativity, and workload models prioritise quantifiable outputs over pedagogical experimentation. Educators who innovate, by embedding sustainability audits, low-carbon menu design, or community partnership projects, often do so at personal cost. Their efforts exemplify micro-agency operating within macro-constraints: adaptive strategies emerging in systems resistant to deep change. These dynamic reveals that SE integration is not merely a pedagogical challenge but a matter of institutional identity and governance.

Constructivist theory provides insight into the fragmented nature of sustainability understanding within hospitality education. Educators interpret “sustainability” through the lens of their disciplinary norms and institutional contexts, constructing meaning socially within their academic communities. Consequently, sustainability often competes with long-established priorities such as employability and operational efficiency.

Transformative learning theory, by contrast, explains how genuine progress occurs when both educators and students experience cognitive dissonance that challenges these assumptions. As Mezirow (1991) [36] and Frank et al. (2024) [39] argue, transformation arises from critical reflection triggered by discomfort or contradiction. Educators in this study who engaged students in experiential projects, such as sustainability audits or campus waste analyses, created precisely such reflective turning points. These activities moved learners from abstract discussion to embodied understanding, translating sustainability from rhetoric into lived experience.

5.1. Transformative and Constructivist Learning in Action

The findings reveal that several educators are reframing their roles from transmitters of information to co-learners who construct sustainability meaning alongside students. This reflects constructivist pedagogy, where learning emerges through active engagement, dialogue, and reflection rather than passive reception [29,30,33]. In practice, educators who embedded sustainability across core units found that students were more likely to view it as integral to hospitality education rather than an elective concern.

Authentic assessment practices illustrate this pedagogical shift in action. In one programme, students conducted low-carbon menu projects, auditing ingredient sourcing, energy use, and waste streams to propose measurable improvements. Another initiative required learners to map supply chains, tracing the environmental and ethical implications of procurement decisions. Reflexive journals and peer-led sustainability audits further encouraged students to examine personal values and professional assumptions, fostering transformative reflection [36,37]. Through these activities, learners moved from cognitive awareness to action competence, the confidence and capacity to apply sustainability thinking beyond the classroom.

Despite these innovations, most programmes still lack reliable mechanisms to evaluate the impact of sustainability learning, echoing the observations of Wang et al. (2024) [27]. However, the emergent models identified in this study offer tangible pathways toward measurable impact, aligning with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Authentic assessments such as sustainability audits, reflective journals, and cross-disciplinary capstone projects link theory to practice by integrating cognition, emotion, and behaviour. These forms of learning also generate measurable indicators, carbon-reduction data, behavioural-change narratives, and partnership outputs that universities can embed within quality-assurance frameworks. When integrated into institutional reporting, such assessments transform sustainability from rhetorical commitment into verifiable educational achievement.

5.2. Bridging Organisational Constraints and Pedagogical Innovation

The coexistence of institutional constraints and individual innovation reveals a crucial intersection between organisational learning and sustainability pedagogy. Viewed through the lens of Argyris and Schön’s (1978) theory [40], universities often operate within single-loop learning cycles—adjusting language, policies, or branding to appear progressive while avoiding double-loop reflection that would challenge entrenched priorities such as workload allocation, resourcing, or governance structures. In this mode, sustainability becomes rhetorically embedded yet operationally peripheral.

Against this backdrop, educators who leverage their industry experience and networks—such as Academic 5’s collaboration with QT Hotels—exemplify double-loop learning. By introducing real-world sustainability practices into their teaching, they generate feedback loops that expose institutional blind spots and model adaptive change. These actions demonstrate distributed agency, where small, context-specific innovations accumulate to reshape organisational culture.

This dynamic extends existing sustainability education [27,38,42], advancing the concept of relational integration, the alignment of pedagogy, governance, and external partnership as interdependent systems. Rather than positioning educators, institutions, and industry as discrete actors, the findings suggest a dynamic ecosystem model in which transformation arises through their continual interaction.

Hospitality education thus serves as a microcosm of organisational transformation. Sustainable change cannot thrive in isolation; it must be reinforced through coherent policy, authentic pedagogy, and responsive industry engagement. In this sense, sustainability education evolves from a curricular addition into an institutional practice, a living system of reflection, negotiation, and adaptation.

5.3. Toward Practical Indicators of Progress

The study identifies a set of measurable indicators that serve as tangible signals of genuine sustainability integration across multiple levels of higher education practice. These indicators translate abstract commitments into actionable metrics, bridging the gap between rhetorical sustainability and evidence-based accountability.

At the curricular level, integration is most evident when sustainability principles are embedded within core unit outcomes rather than confined to electives or specialist topics. This includes explicit learning outcomes referencing environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability, as well as mapped assessment rubrics aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Authentic curriculum indicators also reflect vertical alignment, ensuring sustainability concepts are progressively revisited across foundation, intermediate, and capstone subjects.

At the pedagogical level, authentic assessment provides the most reliable signal of progress. Effective practices identified by participants included sustainability audits, carbon-accounting exercises, reflexive journals, and project-based assignments co-designed with industry. These assessments move beyond theoretical comprehension toward action competence, students’ demonstrated ability to apply sustainability thinking in real-world contexts [10,31]. For instance, low-carbon menu projects, hotel waste audits, and cross-disciplinary sustainability challenges exemplify experiential learning that links cognitive understanding with behavioural change. Such practices also enable measurement of learning outcomes through performance-based and reflective criteria, aligning with emerging international benchmarks for sustainability education [15,19,41].

At the institutional level, the most credible indicators are those that link sustainability to governance and performance systems [16,20,21]. Embedding sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) within academic reviews, curriculum approval processes, and funding allocations ensures alignment between institutional rhetoric and operational reality. Universities that integrate sustainability into staff promotion criteria, strategic planning cycles, and annual reporting frameworks demonstrate double-loop learning, an organisational willingness to reassess priorities and reshape institutional culture in response to sustainability goals [38,40,42].

Finally, partnership indicators reflect the extent to which institutions engage meaningfully with external stakeholders. To consolidate these insights into actionable benchmarks, Table 3 outlines key indicators across curriculum, pedagogy, institutional governance, and partnerships, alongside examples of authentic practice and measurable evidence of progress.

Table 3.

Indicators of Sustainability Integration in Hospitality Education.

Ongoing collaboration with sustainable hotel groups, tourism boards, and local councils provides authentic contexts for applied learning and mutual knowledge exchange. Co-designed research projects, industry internships, and sustainability-focused events generate concrete outputs, such as carbon reduction data, circular procurement models, or community engagement metrics, that can be tracked longitudinally to evaluate impact. Together, these indicators shift sustainability education from symbolic compliance toward evaluative accountability. They offer educators, policymakers, and accreditation bodies a roadmap for benchmarking progress across multiple dimensions of learning and governance. By operationalising sustainability through curriculum, pedagogy, policy, and partnership, universities can move from performing sustainability to practising sustainability, embedding transformative values within their institutional DNA.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how sustainability education (SE) is conceptualised and enacted within Australian hospitality programmes, addressing the persistent gap between institutional rhetoric and pedagogical reality. Guided by constructivist, transformative, and organisational learning theories, the research revealed how educators navigate entrenched constraints while fostering authentic, experience-based learning.

Findings identified four interrelated barriers; institutional constraints, curriculum overload, cultural resistance, and weak industry linkages that limit genuine integration. Yet within these challenges, several enablers emerged: leadership commitment, educator training, and student engagement. Educators who adopted constructivist and transformative approaches created spaces where students co-constructed knowledge through sustainability audits, low-carbon menu projects, and reflexive journals. These practices demonstrate how pedagogy can move sustainability from abstract ideals to lived, measurable learning experiences.

The study extends current frameworks by introducing the concept of relational alignment, which views pedagogy, governance, and industry collaboration as mutually reinforcing systems. This relational lens underscores that sustainability integration depends not only on curriculum reform but also on institutional culture, professional values, and cross-sector partnerships. For policymakers and universities, the message is clear: sustainability must evolve from rhetorical commitment to measurable institutional practice through embedded performance indicators and authentic learning design.

6.1. Limitations

The study’s qualitative design and modest sample size (n = 12) limit its generalisability. Data reflect the experiences of Australian hospitality academics, which may not capture the full diversity of global higher education contexts. Additionally, findings rely on self-reported perceptions, which, while rich in insight, may underrepresent institutional or student perspectives. As participation was voluntary, some degree of self-selection bias is possible; however, this was mitigated through purposive sampling across multiple institutions and academic roles, enhancing the diversity and transferability of perspectives. Nevertheless, the depth and contextual richness of participants’ accounts provide valuable insights into the systemic and pedagogical conditions shaping sustainability education in higher education.

6.2. Future Research

Future research should adopt comparative and longitudinal designs to investigate how sustainability integration in hospitality education evolves across different national, institutional, and disciplinary contexts. Comparative studies between regions with established sustainability frameworks (e.g., Europe, Australia, and East Asia) and emerging economies could reveal how policy, culture, and industry engagement shape implementation pathways. Longitudinal research would further illuminate how institutional reforms and leadership transitions influence the durability of sustainability practices over time.

Mixed-method approaches remain particularly valuable. Quantitative curriculum audits can be combined with qualitative classroom observations and focus groups to triangulate how sustainability competencies are embedded, taught, and assessed. Student learning outcomes, both cognitive and behavioural, should be systematically measured through pre- and post-course evaluations, reflective journals, and performance-based assessments. These designs would strengthen the reliability and transferability of future findings.

Future studies may address key questions such as:

- ➢

- How do leadership commitment and organisational culture influence educators’ capacity to integrate sustainability meaningfully?

- ➢

- In what ways do accreditation standards and external rankings shape curriculum priorities and pedagogical innovation in hospitality programmes?

- ➢

- What forms of industry–academic partnerships most effectively promote authentic sustainability learning experiences?

- ➢

- How do students’ values, cultural backgrounds, and employability expectations influence their engagement with sustainability education?

Emerging technologies also open new avenues for inquiry. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven tools such as adaptive learning systems, curriculum analytics, and automated feedback platforms could be examined for their capacity to support sustainability integration. Future researchers might employ experimental or quasi-experimental designs to assess whether AI-enabled curriculum mapping and formative assessment improve learning outcomes and institutional accountability. Combining AI-based data analytics with qualitative inquiry would allow real-time monitoring of sustainability indicators, offering evidence-based insights for curriculum improvement and policy design.

Collectively, these directions can advance theoretical and practical understanding of how sustainability transitions occur within hospitality education—moving from rhetorical commitment to measurable, systemic transformation.

Together, these limitations and future directions provide the foundation for translating this study’s insights into theoretical and practical implications, as outlined below.

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretical implications: This study extends understanding of sustainability education (SE) within hospitality management by illustrating how institutional culture, curriculum design, and educator agency interact to shape SE integration. It reinforces constructivist, transformative, and organisational learning theories by showing that educators’ reflective engagement and value internalisation are essential to systemic curriculum reform. These findings suggest that sustainability adoption is a relational process linking personal belief systems, pedagogical strategies, and institutional learning mechanisms.

Practical implications: For hospitality schools and universities, the findings emphasise the need to move beyond symbolic initiatives toward structural and cultural alignment. Institutions should provide professional development, allocate time for curriculum redesign, and embed sustainability KPIs into academic performance frameworks. Partnerships between academia and industry are critical to bridging theoretical ideals with operational realities, ensuring graduates develop the competencies required for sustainable hospitality practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.A. and P.D.; methodology, T.A., K.W. and H.A.; validation, P.D., T.S. and T.A.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, T.A., H.A. and P.D.; resources, T.A., P.D., K.W. and T.S.; data curation, T.A. and H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, P.D., K.W. and H.A.; visualisation, T.A.; supervision, P.D., K.W. and T.S.; project administration, T.A. and H.A.; funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Western Sydney University (Protocol No. H13612, 2020-01-21).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, which funded her doctoral research on which this article is based. The author also wishes to thank the journal for considering a discount on the article processing charge (APC), as no institutional or external funding was available to support publication costs. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Grammarly AI to assist with text editing and language refinement. The author reviewed and edited all outputs and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Makoondlall-Chadee, T.; Bokhoree, C. Environmental Sustainability in Hotels: A Review of the Relevance and Contributions of Assessment Tools and Techniques. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giousmpasoglou, C. Working Conditions in the Hospitality Industry: The Case for a Fair and Decent Work Agenda. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAskill, S.; Becken, S.; Coghlan, A. Engaging hotel guests to reduce energy and water consumption: A quantitative review of guest impact on resource use in tourist accommodation. Clean. Respons. Consum. 2023, 11, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Barth, M.; Wiek, A.; von Wehrden, H. Drivers and barriers of implementing sustainability curricula in higher education—Assumptions and evidence. High. Educ. Stud. 2021, 11, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villarán, A.; Guereño-Omil, B.; Ageitos, N. Embedding sustainability in tourism education: Bridging curriculum gaps for a sustainable future. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tavitiyaman, P. Sustainability courses in hospitality and tourism higher education: Perspectives from industry practitioners and students. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 31, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, K.; O’Connor, N.; Condron, R.; Archbold, P.; Hannevig, C.; Honan, D. Examining the alignment of tourism management-related curriculum with the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) in higher education institutions in Ireland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Yoshida, W.; Chano, J. Advancing sustainable hospitality education: A systematic literature review. High. Educ. Stud. 2024, 14, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjozkina, G.; Melanthiou, Y. Is tourism and hospitality education supporting sustainability? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Hung, C.L.; Yen, C.Y.; Su, Y.; Lo, W.S. Enhancing student behaviour with the learner-centred approach in sustainable hospitality education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaffal, T. Investigating Sustainability Education Within Australian Hospitality Management Undergraduate Curricula. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://researchers-admin.westernsydney.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/94926047/uws_70239.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Piramanayagam, S.; Mallya, J.; Payini, V. Sustainability in hospitality education: Research trends and future directions. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2023, 15, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Moreno, S.; Aydemir-Dev, M.; Santos, C.R.; Bayram-Arlı, N. Emerging sustainability themes in the hospitality sector: A bibliometric analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2025, 31, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Cholakis-Kolysko, K.; Dehghan, N. Sustainability teaching in higher education: Assessing arts and design faculty perceptions and attitudes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 1751–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, T.; Timonen, L.; Väänänen, K. Fostering education for sustainable development in higher education: A case study on sustainability competences in research, development and innovation (RDI). Sustainability 2025, 16, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankareddy, S.; Dorfleitner, G.; Zhang, L.; Ok, Y.S. Embedding sustainability in higher education institutions: A review of practices and challenges. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 17, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegiorgis, E.T.; Turner, I. Editorial to the special issue “Narrowing the gap beyond tokenism: Transdisciplinary search for innovative approaches in the integration of indigenous knowledge systems and epistemologies in higher education”. Curric. Perspect. 2023, 43 (Suppl. 1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Alfehaid, M.M.; Alhuqbani, F.M.; Hassanin, M.A.; Ali, O.M.; Uulu, K.N.; Cornelia, P.A.; Salem, A.E. Hierarchical seniority vs. innovation in hospitality and tourism sustainability education: A social exchange theory perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Yarritu, I.; Saez de Cámara, E.; Beloki, N.; Vozmediano, L. The challenge of education for sustainability in higher education: Key themes and competences within the University of the Basque Country. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1158636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G. Integrating sustainability into higher education: Challenges and Opportunities for universities worldwide. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian National University (ANU). Sustainability Progress Report 2024; ANU: Canberra, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://sustainability.anu.edu.au/files/2024-05/Sustainability%20Reporting%20In%20Universities%20.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Education. Australian Universities Accord: Final Report; Department of Education: Canberra, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/final-report (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Australia’s National Statement of Commitment to Transform Education; Australian Government Department of Education: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/download/14780/australia%E2%80%99s-national-statement-commitment-transform-education/30622/australia%E2%80%99s-national-statement-commitment-transform-education/pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Segalàs, J.; Tejedor, G. Faculty empowerment in the sustainability education transition. In The Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Education and Thinking for the 21st Century; Routledge: New Delhi, India, 2025; pp. 452–462. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M.; Hardy, I. Sustainability and the Australian international higher education industry: Towards a multidimensional model. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 13, 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.A.; Nabi, M.N.; Sadeque, S.; Gudimetla, P. Incorporating Sustainability in Engineering Curriculum: A Study of the Australian Universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 576–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.S.; Thanh, L.M.; Tham, A.; Dickson, T.; Le, A. How is the Australian tourism and hospitality curriculum and assessment quality framework perceived elsewhere? a Taiwanese case study. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2024, 24, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Education for Sustainability Alliance (AESA). Education for Sustainability and the Australian Curriculum Project: Final Report for Research Phases 1–3; AESA: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, L.M.; Valle, B.E. Social constructivist teaching strategies in the small group classroom. Small Group Res. 2013, 44, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, B.A.; Miller, K.K.; Cooke, R.; White, J.G. Environmental sustainability in higher education: How do academics teach? Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, D.; Hales, R.; Arcodia, C.; Ferreira, J.A. Overcommitted to tourism and under committed to sustainability: The urgency of teaching “strong sustainability” in tourism courses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 882–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAfnan, M.A.; Dishari, S. ESD goals and soft skills competencies through constructivist approaches to teaching: An integrative review. J. Educ. Learn. 2024, 18, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, L.; Hernawan, A.H.; Dewi, L.; Najmudin, D.; Abdurohim, R. Enhancing teacher competencies in ESD: A framework for professional development. Inov. Kurikulum 2024, 21, 2305–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J.; Marsick, V. Education for Perspective Transformation: Women’s Re-Entry Programs in Community Colleges; Centre for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning as discourse. J. Transform. Educ. 2003, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, J.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Buessing, A.G. Emotions and transformative learning for sustainability: A systematic review. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, L.V.; Leal Filho, W.; Pedrozo, E.Á. Transformative organisational learning for sustainability in higher education: A literature review and an international multi-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Henkel, G.; Lysgaard, J.A. Between evidence and delusion: A scoping review of cognitive biases in environmental and sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 1477–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]