1. Introduction

Frequency of contact is a key dimension of intergenerational solidarity [

1]. Especially in old age, contact with children is important not only in regard to quality of life, loneliness, and social isolation [

2] but also for receiving timely practical and informational help and feeling safe and trusting of help in case of need. It has been shown that high frequency of contact with children is indeed correlated with more intense exchange of social support [

3], emotional closeness [

4], and less frequent symptoms of depression [

5]. All these aspects became especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, to investigate the quality of intergenerational relationships, the frequency of contact among adult generations is the key issue to study.

While this holds true for all families irrespective of their migration status, that is, whether they live in their country of birth (non-migrants) or in a country other than their country of birth (migrants), migration challenges the frequency of contact between children and parents and, as a consequence, generates feelings of loneliness, social isolation, and non-access to help and support from children. As the shares of the population with migration experiences grow in most European countries for reasons such as labour migration, amenity migration, and conflicts [

6,

7], it becomes increasingly important to study the intergenerational relations of older adults who have migrated to a country other than their country of birth.

In this study, we define a migrant as a first-generation, foreign-born respondent currently residing in a SHARE country and a non-migrant as a native-born respondent in their own country. We employ this binary indicator of migrant status to maintain comparability across 25 countries and three repeated cross-sections and to preserve sufficient statistical power. We acknowledge, however, that this broad definition aggregates diverse subgroups such as by region of origin, age at migration, and language proficiency; we note this as a limitation and an important direction for future research.

Frequently it is assumed that migrants may have less contact with their parents than non-migrants would. This is attributed mainly to continued stay of the parents’ generation in the country of origin, meaning that it lives in a different country (which is often but not always the country of birth of the migrated children); however, it also holds in the special case of retirement migration (see [

8] for an overview). Especially if migrants move in early adulthood, they may ‘detach themselves to a greater or lesser extent from their parents’ and their siblings’ generations, and a consequence [constitute] an attenuated kin support network in old age’ ([

6]: 316). Conversely, at least in northern parts of Europe, it is also assumed that migrants have more frequent contact with their children than do non-migrants because they rely more strongly on a family-centred network while non-migrant individuals can resort to wider social networks including both family members and friends [

9]. However, as contact today is not only possible face-to-face but is easily accomplished via telephone, e-mail, video calling, and so on, frequency of contact between migrants aged 50 and above and non-migrants aged 50 and above may be largely independent of physical distance; modern technology may have had such a levelling effect that the frequency of contact between migrant and non-migrant populations would not differ [

10]. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic may have had different effects on these migrants and on their family members. A stronger decrease in contact frequency among the older migrant population than among the non-migrant population, caused by the pandemic, is to be assumed, such as one based on the on-average lower socioeconomic status of migrants compared with non-migrants, making it more difficult to realise a high frequency of contact in terms both of money and of time available. Recent evidence also stresses that not only international migration but even repeated internal migration trajectories may disrupt family-centred social networks, leading to more geographically dispersed ties and lower frequency of contact, though often without reducing overall satisfaction [

11].

In this paper, we apply an empirical approach using descriptive and multivariate methods to investigate the frequency of contact between parents and children who do not live in the same household, differentiating between migrant and non-migrant populations in Europe. Using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, [

12]), we analyse the frequency of contact between adults aged 50 and older with their adult children and the frequency of contact with their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using SHARE data from the 2021 COVID-19 wave, we compare frequencies of adult children’s contact with elderly parents among migrant and non-migrant populations in Europe and contrast these results with those from earlier waves of SHARE (Wave 7 from 2017 and Wave 8 from 2019, shortly before the pandemic erupted in early 2020). Hence, we examine differences across three repeated cross-sections (2017, 2019, 2021) to describe patterns of contact before and during the COVID-19 period.

We frame intergenerational contact as a health-equity concern. By health equity, we mean the absence of systematic, avoidable disparities in health and in the social determinants of health across population groups. Regular parent–child contact functions as a conduit for instrumental help (such as shopping, transportation, and arranging care), informational support (such as navigating services), and emotional connection—all linked to help-seeking and wellbeing in later life. If migrant and non-migrant families differ in their capacity to sustain contact—due to cross-border separation, economic pressures, or unequal access to digital communication—then access to these support resources may be unequally distributed. Understanding these differences is therefore relevant to designing sustainable and inclusive care systems.

Framing intergenerational contact within this broader context allows us to explore how demographic change, digitalization, and migration intersect with the sustainability of informal care networks and their implications for ageing policy.

Conceptualising Sustainability in the Present Study. In the context of this research, sustainability refers to the capacity of intergenerational and care systems to persist and adapt over time while promoting fairness and inclusion. This concept of social and health-system sustainability emphasises the maintenance of supportive family relations and their complementarity to formal health and welfare structures. Understanding how these ties are sustained among both migrant and non-migrant populations offers insights into the resilience and equity of Europe’s ageing societies.

From a theoretical perspective, intergenerational contact is a form of social capital that abets both health equity and the sustainability of care systems. Regular interaction between older adults and their children provides the former with instrumental support, facilitates their navigation of healthcare services, and strengthens their emotional wellbeing, thereby shaping equitable access to health-related resources. For migrant families, constraints on maintaining such contact may reflect structural disadvantages, including economic hardship, distance, or digital barriers, that translate into unequal opportunities for support. At the same time, resilient intergenerational ties reduce reliance on formal services and enhance the social sustainability of welfare systems by complementing the institutional provision of care. Therefore, by framing intergenerational contact in terms of health equity and sustainability, we provide a clear rationale for comparing migrant and non-migrant populations across Europe.

2. Research Questions

Guided by the literature on intergenerational solidarity and health equity, this study addresses two main questions.

RQ1: Do older migrants and non-migrants differ in the frequency of contact with their adult children and their living parents?

RQ2: How do these patterns compare across three repeated cross-sections of SHARE, conducted before and during the COVID-19 period (2017, 2019, and 2021)?

By focusing on these questions, we aim to shed light on whether and how migration status intersects with intergenerational contact in later life and whether broader social disruptions such as the pandemic altered these dynamics.

3. Literature Review

The population that has migrant status, while sharing the experience of migration across an international border, is very heterogeneous in other respects [

13]. Educational background, cultural and religious traditions, and economic conditions are most likely even more diverse among migrants than within non-migrant populations [

14,

15]. For example, [

6] differentiate between ‘the millions of labour migrants who, from the late 1940s, moved either from south to north within Europe or into Europe’ (2004: 311) and ‘northern Europeans who, when aged in the fifties or sixties, permanently or seasonally migrate to southern Europe for retirement’ (2004: 312). Examples of the latter are British pensioners in France or German pensioners in Spain (2004: 312) and other smaller groups such as persons who move internationally ‘to live near (and some with) their relatives’ (2004: 312) and provide care, such as for grandchildren. The crossing of an international border may have happened early, as occurs most often, but it takes place later in the life course, causing many older migrants to live in the host country for decades.

Kofman et al. [

16], describing the literature on family solidarity in extended migrant families, encounter strong intergenerational solidarity. ‘It is often assumed’, they comment, ‘that migrant families are special in this respect, and that non-migrant families in the course of modernisation have lost their solidarity potential beyond the nuclear household. However, the burgeoning research literature on contemporary family and kinship relations in Western societies provides a different picture. It shows that the family is still a key system of social support among all living generations, and thus a strong pillar of the welfare mix of these societies’ ([

16]: 31). Adult children and their elderly parents live rather close to each other (although most frequently not in the same household), feel close to each other emotionally, have frequent contact with each other, and give mutual support by helping in several ways [

17].

Focusing on differences in frequency of contact among migrant and non-migrant families throughout Europe, ref. [

18] report more frequent contact between parents and adult children in migrant families than in non-migrant families when analysing parent–child dyads in SHARE. This may be attributed to more family-oriented values in some cultures than in others [

19]. It may also reflect higher shares of co-residence with adult children in migrant families, although co-residence may be due not only to family-orientation but also to economic status and care responsibilities (for both the elderly and the children). In addition, the literature mentions smaller social networks beyond family members among the migrant population as well as a stronger focus on the family as potential compensation for the loss of friends, neighbours, and other relatives due to the migration itself [

20]. In single-country studies such as [

9,

21], it is found that frequency of contact is more intense in families of Turkish migrants than in families of non-migrant German residents, possibly reflecting these processes. However, especially when migration takes place earlier in the life course, the greater risk of intergenerational and intercultural conflict may also result in conflict and reduced frequency of contact [

20]. Geographical distance is also mentioned as a determinant of frequency of contact, but this becomes much less important when we take modern technology into account [

10,

22]: Video calls and messenger apps are used with growing frequency and abet frequent contact even in cases of very large distances among family members of all generations or in cases of lockdowns during the pandemic [

23].

Relatedly, research on ‘empty-nest’ transitions shows that reduced day-to-day interaction with adult children is experienced very differently across cultural contexts—for some parents as loneliness, distress, or loss of role, for others as relief or autonomy gained. These responses are shaped by norms regarding filial obligation, co-residence, and parental roles—norms that may differ between migrant and non-migrant families. By connecting our structural results to this literature, we see why similar contact frequencies may carry distinct emotional implications across groups [

24].

Several recent studies also have used the SHARE data to analyse intergenerational contact within the family during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ref. [

25] find that help from children to their parents increased at the beginning of the pandemic while help provided by parents to children dropped. This changed over time. Frequency of contact, however, was not targeted in their study. Ref. [

10], studying frequency of contact, find an increase in intergenerational contact on average but the opposite pattern some subgroups, especially old men, the less well educated, and nursing-home residents. Ref. [

10], however, do not take migration into consideration in their paper.

The life-course perspective and the embeddedness of individuals in extended families and different cultures help to explain the complexity of the frequency of contact between elderly migrants and their children and vice versa. This may be true especially at times of a pandemic that reminded us of the existence of international borders and the possibility of closing them in the event of a crisis, when different national regulations applied even within the European Union. In this paper, we focus on the effect of migration on frequency of contact at three points in time within families of older individuals aged 50 and above. The inquiry takes place irrespective of the biographical timing of the migration event because migration leaves an enduring effect on family structures, some relatives staying in the country of origin and other relatives joining the migration process at some point in time.

4. Data and Method

4.1. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)

We use data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). The data collected in SHARE offer a unique way to compare the family, health, economic situation, and welfare of people aged 50 and above in different European countries over time. SHARE is a multidisciplinary cross-national bank of microdata on health, psychological, and economic variables [

26]. The SHARE survey is partly harmonised with leading international surveys such as the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), and the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). It is also a prime resource for newer surveys of its type in a range of countries such as Japan (JSTAR), China (CHARLES), India (LASI), and Brazil (ELSI) [

12]. We use the seventh, eighth, and COVID-19 waves of the survey (data collected in 2017, 2019, and 2021, respectively) for cross-sectional analyses that, first, allow for comparison of the contact behaviour of population groups such as migrants versus non-migrants, and second, focus on change in the frequency of contact with parents and children over time at the aggregate level. Given that our analyses are based on repeated cross-sections rather than longitudinal change models, we refrain from inferring within-person stability or change.

4.2. Variables

We analyse two dependent variables: The first is frequency of contact between individuals aged 50 and above and their children. Results are based on individuals who have at least one child and report to have had contact with at least one child. Second, we analyse frequency of contact between individuals aged 50 and above and their parents, based on individuals with at least one living parent and reported contact with at least one parent.

Frequency of contact with adult children is categorised as contact with the most frequently contacted child, ranging in this study from ‘about once a month or less’, ‘about every week or every two weeks’, and ‘several times a week’ to ‘daily’. Results reported refer to the population with children; childless individuals aged 50 and above are excluded. Furthermore, those who reported to have ‘never’ contact with their children had to be excluded from our analyses because in the COVID-19 wave, it remains unclear if ‘never’ should be interpreted as childlessness or as no contact with child. The reason for this is that no filter question was applied in the COVID-19 wave questionnaire of SHARE, as opposed to Waves 7 and 8, in which only individuals who had living children were asked about the frequency of contact with their children.

Accordingly, frequency of contact with parent is categorised as contact with the most frequently contacted living parent, ranging in this study from ‘about once a month or less’, ‘about every week or every two weeks’, and ‘several times a week’, to ‘daily’. Results reported relate to the population that has at least one living parent, to the exclusion of individuals aged 50 and above whose parents have died. In addition, the group of those who reported ‘never’ having had contact with their parents are excluded. Again, this was decided because in the COVID-19 wave of SHARE, it remains unclear if ‘never’ should be interpreted as both parents deceased, as may be the case among most individuals aged 50 and above included in SHARE, or as at least one parent still alive but totally out of contact with the individual. The lack of a filter question in the COVID-19 wave questionnaire obviously confused many respondents. For example, nearly one third of respondents aged 70–79 reported having had no contact when given the COVID-19 wave questionnaire, as against only 6 percent in Waves 7 and 8, where a preceding question on living parents filtered out respondents who had no living parents.

Given the difference in measures between the COVID-19 wave questionnaire and the preceding waves of SHARE (7 and 8), we also recategorised the answers in order to obtain a comparable measure for all three waves analysed. Because the response categories varied slightly across the waves, we harmonised them into five categories (daily, several times/week, about once/week, less often, never). For the COVID-19 wave, where ‘never’ may partly capture temporary restrictions rather than long-term absence of contact, we interpret the results with caution and note the possibility of bias. The original questions were more differentiated in the COVID-19 wave concerning types of contact but more differentiated in Wave 7 and Wave 8 concerning frequency of contact (the same answering categories applied to contact with own children and contact with own parents):

- (1)

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, how often did you have personal contact, that is, face-to-face, with the following people from outside your home? Own children: Was it daily, several times a week, about once a week, less often, or never? Own parents: Was it daily, several times a week, about once a week, less often, or never?

- (2)

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, how often did you have contact by phone, email, or any other electronic means with the following people from outside your home? Own children: Was it daily, several times a week, about once a week, less often, or never? Own parents: Was it daily, several times a week, about once a week, less often, or never?

We combined the two types of information on contact—personal and via phone, email, or other electronic means—into one variable in order to have a measure that is comparable to Waves 7 and 8, as there was no differentiation between face-to-face and other modes of contact:

- (1)

In the past twelve months, how often did you have contact with (name of child) either in person or by phone, mail, email, or any other electronic means? Daily, several times a week, about once a week, about every two weeks, about once a month, less than once a month, never.

- (2)

In the past twelve months, how often did you have contact with (your mother/your father) either in person or by phone, mail, email, or any other electronic means? Daily, several times a week, about once a week, about every two weeks, about once a month, less than once a month, never.

We reduced the number of answering categories to four in order to make the results in 2021 comparable with those in 2017/2019 in terms of the cross-sectional distributions, ranging from 1 (less than once a week) to 4 (daily).

As an independent variable of interest, we focus on migration status. Migration status is coded 1 for respondents who were born outside the country of current residence (foreign-born) and 0 for respondents born in the country (native-born). This operationalisation yields a consistent binary measure across countries and waves. As controls we use indicators that are known to be of relevance from the sociological literature on intergenerational relationships [

27]. In addition to gender and age groups, the indicators are education (years of schooling), self-rated health (on a five-point scale: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor; the higher the value, the worse is one’s health), and subjective assessment to ability to make ends meet (arrayed on a four-point scale: 1 = with great difficulty, 2 = with some difficulty, 3 = fairly easily, 4 = easily). Furthermore, we insert dummies for the 25 countries for which we have data at three points in time, from Wave 7 (2017), Wave 8 (2019) and the COVID-19 wave (2021): Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. In the models estimated, we use Germany as reference category because it is the most populous country on the list. The inclusion of various countries takes account of differences in intergenerational relationships among welfare regimes among European countries, with more co-residence as well as more intense contact between generations in Southern Europe than in Central and Northern Europe [

28].

4.3. Methods

We employ descriptive and multivariate regression analyses (ordinary least squares with country fixed effects) to examine the frequency of intergenerational contact. Analyses are based on repeated cross-sectional data from SHARE Waves 7–9.

4.4. Sample Description

In the samples for our analysis (

Table 1, unweighted results), the average reported frequency of contact with children in each wave is somewhat higher (3.36, 3.26, and 3.30) than the average reported frequency of contact with parents (2.81, 2.80, and 3.02). There are more women than men in all waves—7, 8, and COVID-19. The samples of those with living parents are comprised mainly of individuals aged 50–59 and 60–69, making this sample somewhat younger than the sample with at least one child. The share of migrants varies from 6 percent to 10 percent in our analysis samples.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Results

As the following findings in this paper are based on migrant and non-migrant individuals who had at least one child and those who had one living parent, it is important to see first whether the two groups differ systematically in the share of those who have children or have parents. In the European countries included in this analysis: there are no such differences between migrant and non-migrant populations were not found; less than 10 percent of both the migrant and the non-migrant elderly populations aged 50 and above are childless. While there is some evidence of a slow but steady increase in the share of childless individuals, in most countries this is currently a phenomenon among individuals in their forties, who will reach old age only in the long run, beginning in the 2040s (see, for example, [

29] for the case of Germany).

What we may observe, however, is that the SHARE populations differ to some degree, as the percentages of those with at least one living parent are much higher in Wave 8 and the COVID-19 wave than in Wave 7. While a slight increase in 2021 relative to 2017/2019 in the cross-sectional distributions would be plausible due to increases in longevity, it is also plausible to assume differences in the SHARE samples over time with younger refresher samples in later waves.

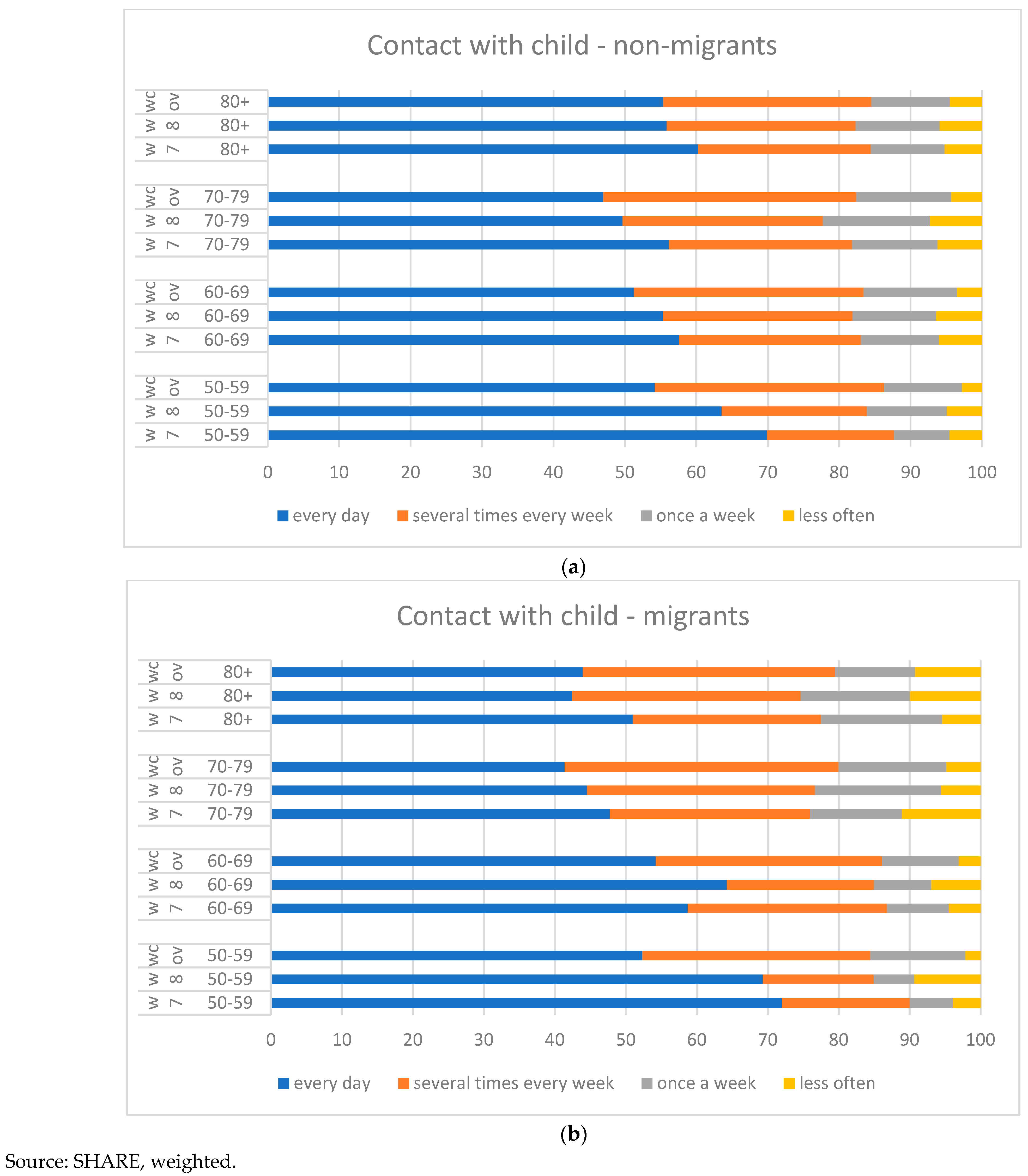

Among those with children, the frequency of contact with their children is high among the non-migrant population in all European countries included in our analysis. Most non-migrant individuals aged 50 and above who contacted at least one child reported daily contact. The second most frequent category is contact several times a week. Hence, fewer than 20 percent had contact only once a week or less often. In a comparison of age groups, daily contact with children is most widespread among those aged 50–59, followed by those aged 80 and above (

Figure 1a). Less frequent contact than once a week is rare among all age groups. Comparing in 2021 with 2017/2019 in the cross-sectional distributions, we found that non-migrant individuals are slightly less likely to report daily contact with children in the COVID-19 wave; the shift was not toward overall less frequent contact but toward having contact only several times a week.

As for the migrant population aged 50 and above, again, we find high frequency of contact with children (

Figure 1b). Comparing across age groups, however, the differences among age groups are more pronounced in the migrant population than in the non-migrant population. Daily contact is much more widespread among those aged 50–59 and 60–69 but not among those aged 70–79 and 80 and above. Concurrently, about 20 percent of the two oldest age groups have contact with children only once a week or less frequently in the migrant population. Comparing across waves, daily contact is weaker in the COVID-19 wave than in Wave 7 and Wave 8, but this small change is compensated by the increase in contact several times a week, leaving the percentages of respondents with contact once a week or less often rather stable.

By comparison, the elderly migrant population with children generally reports slightly less frequent contact with children. Especially daily contact is somewhat less frequent in the age groups aged 70 and above. The differences in 2021 relative to 2017/2019 in the cross-sectional distributions, however, are very similar to those among the non-migrant population: We see a minor shift from daily contact to contact several times a week but no increase in contact once a week or less often.

Overall, the reported frequency of contact with parents is much lower among individuals aged 50 and above throughout Europe than the frequency of contact with children (The pattern of contact with parents less frequently reported by parents than by children is well documented [

30,

31], for example, argue: ‘There may also be some tendency to overreport contact with children and/or underreport contact with parents—a response pattern associated with the often-observed difference in the “developmental stake” of parents and children’ ([

31]: 169)). About one-third of the non-migrant population with parents still alive has daily contact with parents and roughly another third has contact only once a week or even less often (

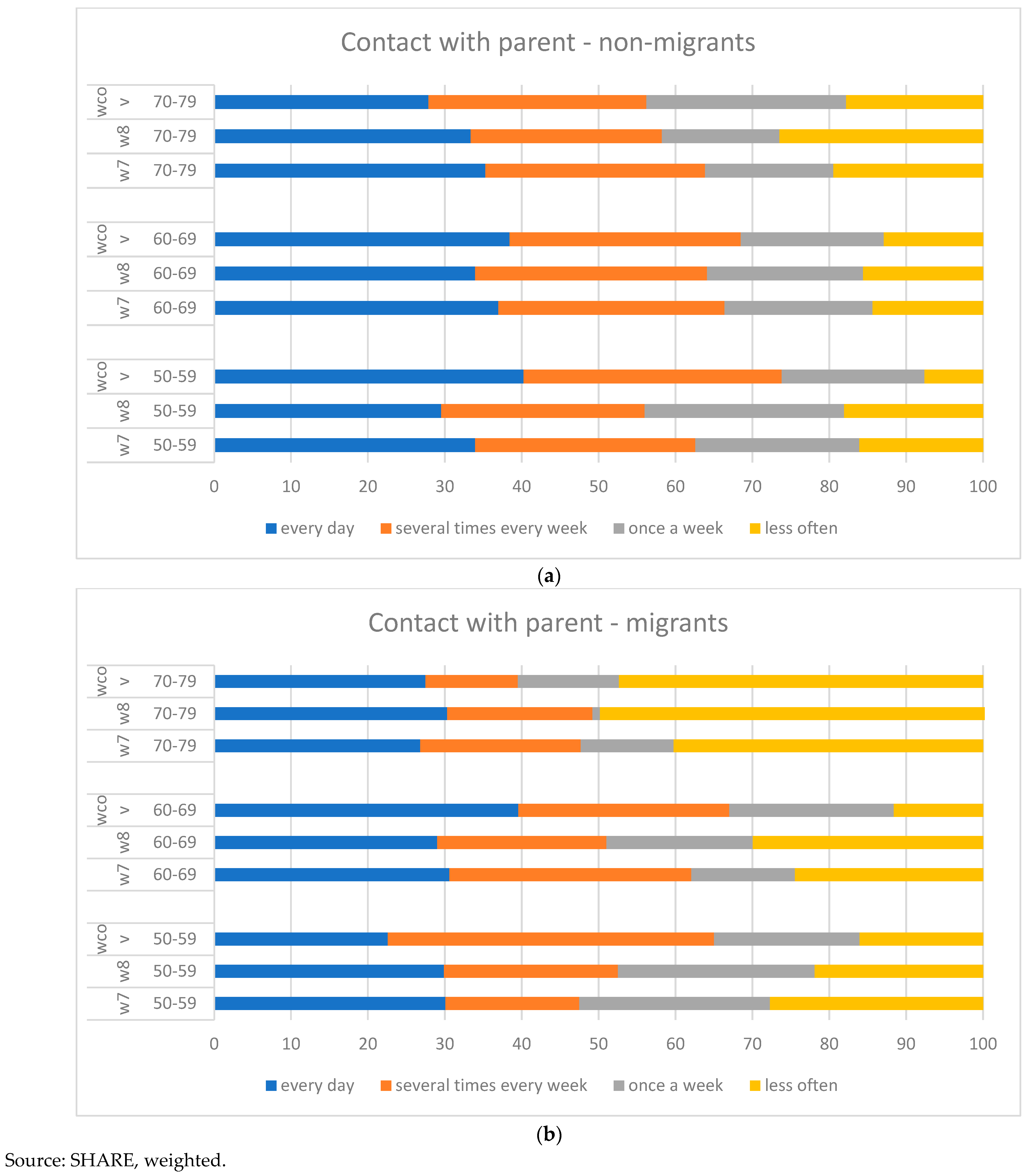

Figure 2a). Comparing across age groups, the frequency of contact with parents is highest among those aged 60–69 in the non-migrant population. Comparing across waves, we find diverging patterns among different age groups: While those aged 50–59 seem to have intensified their contact with parents during the pandemic, those aged 70–79 show a smaller share of daily contact in the COVID-19 wave than in Wave 7 and Wave 8.

Among the migrant population aged 50 and above, the frequency of contact with parents is generally somewhat lower than among the non-migrant population aged 50 and above throughout Europe. Comparing age groups, having rare contact with parents—less often than once a week—is much more widespread among migrants aged 70–79 than among those aged 50–59 and those aged 60–69 (

Figure 2b). Comparing waves, migrants aged 50–59 have a larger share of contact at least several times a week in the COVID-19 wave than in Wave 7 and Wave 8, a finding again very similar to the pattern described among non-migrant individuals aged 50–59.

This difference relative to the non-migrant population is most likely a result of the migration event, as older migrants who immigrate to a European host country as first-generation migrants usually have parents who remain in the country of origin. In addition, life expectancy is lower in many countries of origin than in the European host countries included in this analysis. However, as these results reflect average values across 25 European countries and varying sociodemographic and socioeconomic individual characteristics, differences in frequency of contact with family members of different generations should be investigated by estimating multivariate models.

5.2. Multivariate Results

The estimated multivariate models focus on the research question of the impact of migration status on the frequency of contact with children respective contact with parents. The effects are calculated using linear (OLS) regression models for each wave included in our analysis.

As for frequency of contact with adult children, the effect of migrant status is positive and statistically significant at all three points in time investigated: Migrants aged 50 and above have more frequent contact with children than do non-migrants across the 25 European countries included in the analysis (

Table 2). The effect sizes are 0.040 in Wave 7, 0.092 in Wave 8 and 0.066 in the COVID-19 wave; they can be described as weak effects and they do vary only slightly. That is, the difference between the elderly non-migrant and migrant population is comparatively small when it comes to frequency of contact with adult children, as in both groups, the frequency of contact with children is on average very high (in the subpopulation analysed—individuals aged 50 and above who have at least one child and some contact with the child)—with migrants having even slightly more contact. While this is somewhat contrary to our observation in the descriptives (

Section 4.1), it may be especially reflective of the higher frequency of contact in the 50–59 age group. Furthermore, we found no evidence of a varying change in contact behaviour during the pandemic in the two groups, non-migrant and migrant-born: contact with children remained high among both groups during the pandemic. Also, the small group differences persisted, with migrants having slightly more frequent contact with their children.

In addition, the results of the multivariate models show that fathers aged 50 and above have less frequent contact with their children than do mothers at all points of time investigated. This effect, well-known in the literature [

32], follows rather traditional gender-specific roles within families, as mothers bear the main responsibility for maintaining contact within families and also with friends and the wider social network. The results also show that older individuals have less frequent contact with their adult children than do those aged 50–59, the reference group in the model. Furthermore, frequency of contact with children varies among countries that represent different welfare regimes, with more frequent contact in Southern and Eastern European countries and less frequent contact in Northern European countries.

As for frequency of contact with living parents, the effect of migrant status is negative with effect sizes of −0.279 in Wave 7, −0.167 in Wave 8 and −0.059 in the COVID-19 wave (

Table 3). However, this effect is statistically significant only in Wave 7. This means that migrants aged 50 and above have less frequent contact with parents than did non-migrants in 2017 across the 25 European countries included but that this finding does not attest during the pandemic. However, one should not interpret this as evidence of a change in contact behaviour in 2020 due to the pandemic because the results of Wave 8, preceding the onset of the pandemic, are very similar. And today, as technical means of communication are widely available at low cost, geographical distance and/or international borders are no longer a real hurdle to contact, although some groups (such as those of low income and those living in remote and rural areas) may be especially disadvantaged in this regard.

Consistent with the findings on contact with children, we again find a strong gender effect, sons aged 50 and above having significantly less frequent contact with parents than daughters aged 50 and above. In addition, we see strong differences between countries in different welfare regimes, with large positive effects in Southern European countries: individuals aged 50 and above are in much more frequent contact with parents in these countries than in Germany (the reference country in our model). Similar to the findings on frequency of contact with children, there is evidence of less frequent contact in Northern European countries, such as Denmark, Sweden and Finland, than in Germany as well as in Southern European countries.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we focused on populations aged 50 and above and analysed both directions of intergenerational contact: frequency of contact with parents and with adult children. Our findings provide clear answers to both research questions. First (RQ1), migrants and non-migrants show systematic differences in contact frequency with both children and parents. Second (RQ2), the cross-sectional distributions of contact remained largely similar across the three survey waves, with only modest shifts during the COVID-19 period. Together, these results highlight the resilience of family ties in later life while underscoring important disparities associated with migration status. Although many differences are statistically significant, they must be interpreted against the generally high baseline of contact across groups. Thus, differences, while systematic, are often modest in substantive size. From a health equity perspective, these disparities matter because reduced opportunities for intergenerational contact may translate into unequal access to social support, with implications for wellbeing and care in ageing populations.

Migrants aged 50 and above have less frequent contact with their parents and more frequent contact with their children than does the non-migrant population across the European countries investigated. In repeated cross-sections, population-level distributions were similar before and during the COVID-19 period, leaving the differences between the migrant and the non-migrant populations rather stable during the pandemic. This may be the result of an increase in use of video calls and messenger apps. (If so, access to these technologies is of course a precondition, pointing to social inequalities that we were not able to study directly in this paper). New technologies facilitate contact between adult children and parents in general [

33]. In SHARE, however, it is not possible to empirically differentiate in type of contact between face-to-face and via telephone or digital technologies when comparing frequency of contact in 2021 relative to 2017/2019 in the cross-sectional distributions, that is, before and during COVID-19.

Frequency of contact is at the heart of intergenerational contact within families due to its impact on quality of life. As contact between family members can be such as a protective factor in preventing feelings of loneliness and a condition for the receipt of social support, it is important to discover from our descriptive results that the frequencies of contact fell only slightly during COVID-19, with only small shifts and more contact several times a week instead of daily contact. From the standpoint of equity, less frequent contact may signal structural barriers to support that policies (such as digital inclusion, transport and proximity policies, and caregiver leave) can remedy. However, further research is needed to see if contact via telephone or online has the same protective power as face-to-face contact.

It is also found that fathers aged 50 and above have less frequent contact with their children than do mothers at all points in time investigated. This most likely reflects traditional gender-specific roles that also shape, for example, labour-market participation. Similarly, sons aged 50 and above report significantly less frequent contact with their parents than do daughters aged 50 and above.

Frequency of contact with parents may be driven especially by elderly parents’ needs such as healthcare, vulnerability, and frailty, and these needs may intensify both with ageing and in a pandemic. However, not all groups could step up the frequency of contact with their parents during the pandemic to the same extent, as shown in the descriptive results. We interpret these findings as examples of existing difficulties in realising higher frequency of contact with parents among the elderly migrant population. This may trace to socioeconomic factors such as an on-average lower socioeconomic status or larger geographical distances between familial generations in migrant families than in non-migrant families. As face-to-face contact is a condition for instrumental help from children, some groups of migrants aged 50 and above may be less able to support elderly parents than are non-migrants aged 50 and above. In addition, migrants aged 50 and above may be more dependent and rely more on their own adult children.

These findings have broader implications for sustainable healthcare systems and intergenerational care models. As populations age and healthcare systems face growing resource constraints, families’ capacity to provide informal support becomes a key pillar of sustainability. Our results suggest that this capacity is unequally distributed. Migrants aged 50 and above, who report less frequent contact with their parents, may face greater challenges in providing support across borders—whether due to geographic distance, economic pressures, or unequal access to digital tools. These barriers may exacerbate health disparities in later life, particularly if reduced contact limits access to timely emotional or practical assistance. Promoting equitable access to digital communication technologies, as well as strengthening informal care networks through supportive policy, should therefore be considered integral to sustainable and inclusive approaches to health management in diverse ageing populations. In this sense, sustaining intergenerational contact represents a core mechanism of social sustainability, reinforcing the continuity of informal support and ensuring that care systems remain adaptive and inclusive in the face of demographic ageing and migration.

7. Conclusions

Given the importance of contact for quality of life in old age and as a condition for the provision of help, support, and prevention of loneliness among adults of different familial generations, it is important to study the frequency of contact between parents and adult children and changes in this parameter over time in greater detail. In the foregoing comparison of patterns of frequency of contact of adults aged 50 and above who have adult children as well as their frequency of contact with living parents between non-migrant and migrant populations in Europe, we see on average a high frequency of contact between familial generations among all families irrespective of migration status. The results of our analyses, based on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), reveal that migrants aged 50 and above have only slightly less frequent contact with their parents and slightly more frequent contact with their children than do the non-migrant population in Europe.

COVID-19 challenged intergenerational contact in many ways. The two groups investigated, however, hardly changed the frequency of contact behaviour, differences between the migrant and the non-migrant populations remaining rather stable over time. Again, this holds for migrant and non-migrant families alike, and it shows the importance of social interaction between individuals from different familial generations even, or especially, in more difficult times such as during a pandemic. Therefore, it would be important to study the different types and means of contact between parents and adult children, such as use of digital technologies, in greater detail in order to understand changes in intergenerational contact within families and to determine how frequency of contact is associated with support given and received in old age in population subgroups such as older migrants over time.

From the perspective of health policy, sustaining intergenerational contact—be it through physical proximity or by digital means—is vital for building resilient informal care systems. Ensuring that older adults, particularly those with a migration background, are not excluded from these support structures is essential for promoting health equity. As Europe continues to age, sustainable innovations in care must address both demographic and social diversity. Policies should promote digital literacy and affordable internet access for older migrants, encourage proximity and mobility solutions (e.g., transport support), and tailor family-support initiatives to the welfare-regime context. Our findings point to the need for inclusive strategies that will strengthen intergenerational ties, support digital access, and recognise family networks as foundational components of long-term health and social sustainability. Overall, the ability of families and communities to maintain regular intergenerational contact—through proximity, mobility, or digital means—should be recognised as a fundamental pillar of social and health-system sustainability in ageing societies.

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is limited in several ways. The first limitation pertains to the available sample of analysis for migrants. As often occurs in migration studies, our sample was restricted to SHARE respondents who lived in the European host country where the survey took place. As some migrants choose to return to their country of birth in retirement, the SHARE sample may be biassed because older migrants with children or grandchildren in the host country are more likely to stay than are those with children or grandchildren living in the country of origin [

34]. To compare the full spectrum of migrants with non-migrants, the sampling would also have to include migrants who returned to their country of birth.

A second limitation is the heterogeneity of the group of migrants, as in terms of migration-specific characteristics such as cultural background, length of stay in the host country, and command of the host country’s language, but also in terms of socioeconomic characteristics. In further research, it would be important to study the specific patterns of subgroups of older migrants in specific settings in host countries, such as the situation of elderly Turkish migrants in Germany or in Sweden, elderly Spanish migrants in France or Austria, and elderly German migrants in Spain, for example, as the structure of family relationships may be a function of characteristics of the country of birth, the host country, and the migration process itself. Our definition of migration status inevitably masks heterogeneity by origin region, migration cohort, and integration characteristics. Future studies that can draw on more detailed data or larger migrant samples should investigate these subgroup differences. In addition, although we control for country-level differences by using fixed effects, our analysis does not examine heterogeneity across broader European regions. Patterns of intergenerational contact may vary systematically between, for example, Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western Europe due to differences in welfare regimes, cultural expectations, and/or migration histories. Given that sample-size constraints prevent us from conducting these subgroup analyses reliably within the current framework, we note this as an important avenue for future research. More broadly, migrants should not be treated as a single homogeneous category. Distinct groups such as labour migrants, retirement migrants, and refugees often face very different opportunities and constraints in maintaining intergenerational contact. These differences may shape the extent, form, and meaning of contact in ways not captured by our binary migrant/non-migrant distinction. This limitation should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings.

A third limitation traces to the data infrastructure of SHARE and pertains to the need to adjust the interview mode and the wording of the question in the COVID-19 wave, as described above. The recommendation for cross-sectional comparisons at different points in time is to use the same measurement in every wave of data collection. Because we analysed repeated cross-sections and somewhat different measures/samples in 2021, we did not model within-person change. All of our temporal statements referred to aggregate distributions across waves.

A fourth limitation is that the study presented here focuses on the quantity of contact only. In further research, the quality of family relationships should be investigated, it being known that positive outcomes of contact among family members depend on relationship quality. Nevertheless, we may conclude that even though COVID-19 challenged intergenerational contact within families, changes in frequency of contact are exceptions, not the rule, and that differences between migrant and non-migrant populations remained largely stable.