1. Introduction

The involvement of companies in the climate crisis is far from negligible, as is their influence on global climate policies to serve their own interests. However, the international climate paradigm decentralizes governance and grants firms a more proactive role in driving sustainable transitions. Achieving the goal of limiting the global temperature increase to below 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels largely depends on political will and institutional capacity, which vary widely across nations [

1].

Improving the business environment can enhance carbon efficiency by promoting green technology innovation and fostering new ventures. Governments play a crucial role by providing fiscal incentives, improving financing channels, and establishing fast-track procedures for green technology implementation, enabling the rapid application of innovative solutions to improve carbon efficiency [

2]. Such technological progress reduces fossil energy consumption, optimizes pollution control, and contributes directly to firms’ energy efficiency [

2,

3].

The Circular Economy (CE) has gained prominence as a model that is more efficient and sustainable in the long term compared to the traditional linear “take–produce–dispose” approach [

4]. At the micro level, various Circular Business Models (CBMs) help firms integrate circular principles into production and operational processes [

5]. At the meso level, inter-firm collaboration occurs through the exchange of residual materials that become inputs for other companies—a practice referred to as industrial ecology or industrial symbiosis [

6,

7].

Investment in Eco-Innovation (EI) represents a key strategy for advancing the transition toward a circular economy and contributing to climate-mitigation goals. EI enhances resource-use efficiency, reduces costs, and strengthens firms’ environmental reputation. However, the adoption of such practices can be limited by financial, regulatory, and cultural barriers, as well as by institutional and market pressures that determine the speed and scope of implementation [

8,

9].

Meanwhile, Sustainable Marketing (SM) encompasses practices aimed at creating value for environmentally conscious consumers while generating social and environmental benefits. This discipline seeks to educate customers and stakeholders, foster continuous improvement, and consolidate a sustainable corporate culture that reflects political, cultural, environmental, and social considerations [

10].

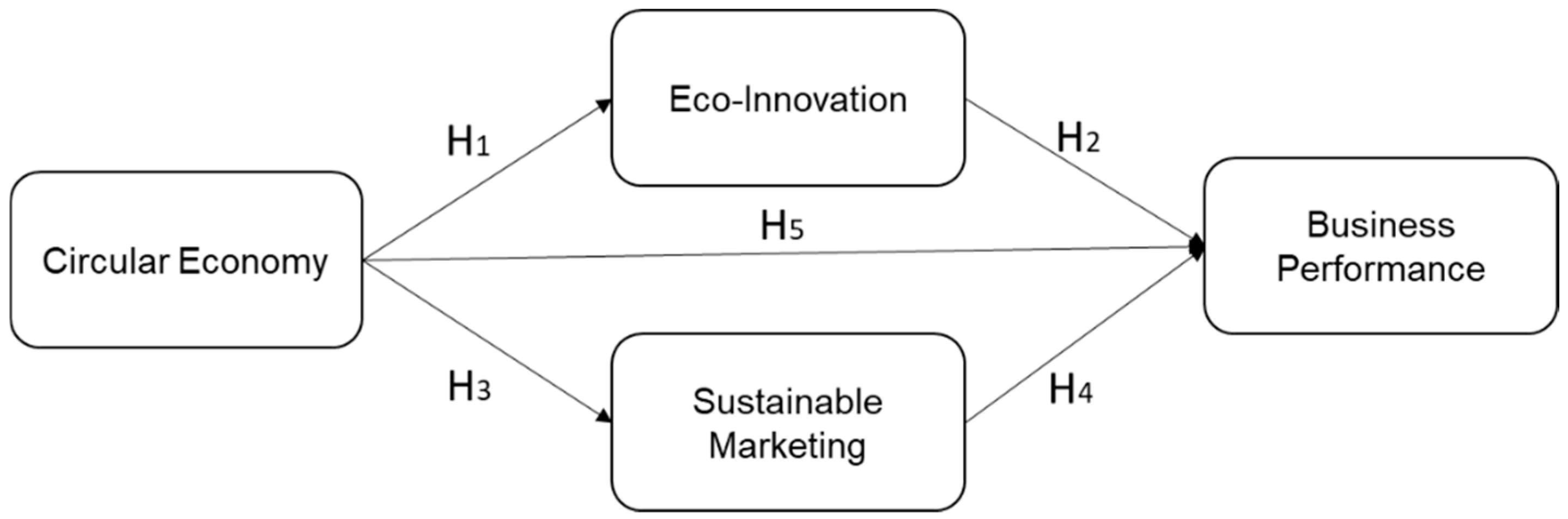

Business Performance (BP) captures firms’ internal and external outcomes, reflecting both operational efficiency and their capacity to adapt to regulatory, technological, and market changes. Effective adoption of CE, EI, and SM has the potential to strengthen BP, generating sustainable competitive advantages and organizational resilience.

Despite extensive literature addressing sustainability-oriented strategies, prior studies have often analyzed CE, EI, and SM separately, providing limited understanding of their combined and comparative influence on BP. Research on the Circular Economy remains fragmented across disciplines and lacks integrative approaches that connect it with innovation and management perspectives [

11]. Likewise, studies on Circular Economy and innovation have largely focused on technological and operational aspects, with limited consideration of broader strategic functions such as marketing or stakeholder engagement [

12]. This gap is particularly relevant for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) operating in emerging economies, where limited resources require careful prioritization of sustainability investments.

Accordingly, this research contributes to the sustainability and management literature by rigorously analyzing the joint and relative effects of CE, EI, and SM on BP, providing empirical evidence from MSMEs located in Aguascalientes, Mexico. The proposed framework is empirically tested through a quantitative modeling approach that evaluates the relationships among these sustainability-oriented strategies and their influence on business performance. This analysis provides a robust basis for identifying which practices most effectively enhance competitiveness and long-term performance in resource-constrained business environments.

The involvement of companies in the climate crisis is far from negligible, as is their influence on global climate policies to serve their own interests. However, the international climate paradigm decentralizes global governance, granting firms a more proactive role. Achieving the goal of limiting the global temperature increase to below 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels largely depends on state political will, as countries differ in capacities, resources, cultures, and commitment to environmental preservation [

1].

Improving the business environment can enhance carbon efficiency by promoting green technology innovation and fostering new ventures. In this context, governments play a crucial role by providing fiscal incentives, improving financing channels, and establishing fast-track procedures for green technology implementation, enabling the rapid application of innovative solutions to improve carbon efficiency [

2]. Such technological progress can reduce fossil energy consumption, optimize pollution control, and directly contribute to firms’ energy efficiency [

2,

3].

CE has gained prominence as a model that is more efficient and sustainable in the long term compared to the traditional linear “take-produce-dispose” approach [

4]. At the micro level, various Circular Business Models (CBM) have been developed to assist firms in integrating circular principles into their production and operational processes [

5]. At the meso level, inter-firm collaboration is analyzed through the exchange of residual materials, which are reused as inputs by other companies—a practice referred to as industrial ecology or industrial symbiosis [

6,

7].

Therefore, investment in EI represents a key strategy to lead the transition toward a circular economy and contribute to climate mitigation goals. Eco-innovation enhances resource-use efficiency, reduces costs, and strengthens firms’ environmental reputation. However, the adoption of these practices can be limited by financial, regulatory, and cultural barriers, which affect companies’ proactivity in addressing environmental challenges [

8].

Meanwhile, SM encompasses practices aimed at creating value for conscious consumers, while delivering societal and environmental benefits. This discipline seeks to educate customers and stakeholders, foster continuous improvement, and consolidate a sustainable corporate culture, taking into account political, cultural, environmental, and social factors [

10].

Finally, BP constitutes a comprehensive measure of firms’ internal and external outcomes, reflecting both operational efficiency and the capacity to adapt to regulatory, technological, and market changes. Effective adoption of CE, EI, and SM has the potential to strengthen BP, generating sustainable competitive advantages and organizational resilience.

Overall, this study aims to identify and analyze gaps in the adoption of CE, EI, and SM strategies in the business sector and their impact on BP. These gaps represent critical points that can be addressed to optimize decision-making, mitigate climate change effects, and maximize positive socio-economic outcomes. The research proposes an analytical framework to facilitate the implementation of sustainable practices and contribute to the development of more resilient and environmentally responsible business models.

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Findings

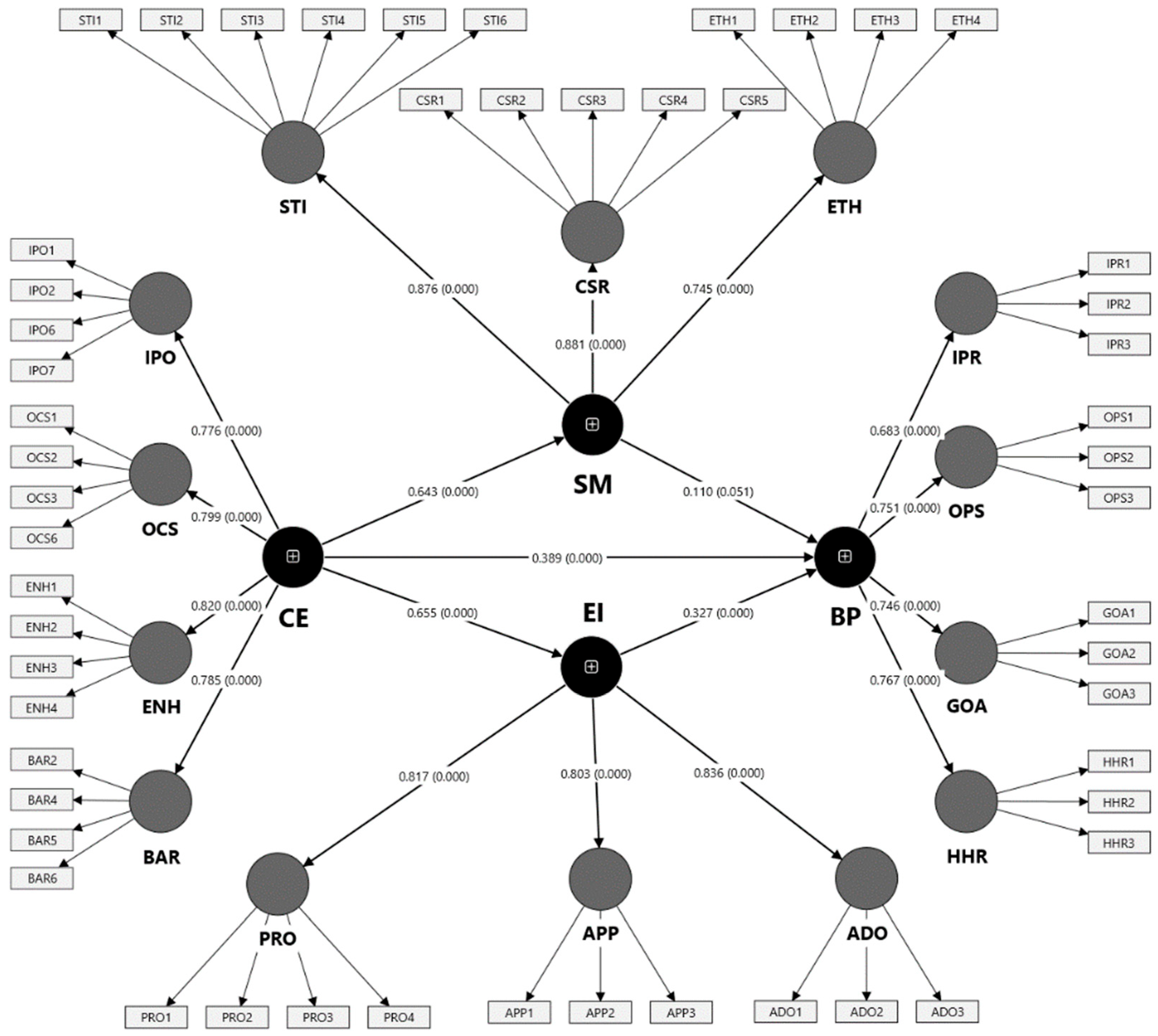

The findings highlight a distinctive pattern among sustainability-oriented strategies. Although CE, EI, and SM share the ultimate goal of improving business sustainability, their impacts on BP unfold through different mechanisms and time horizons. CE and EI display immediate and significant effects, as their implementation directly enhances operational efficiency, resource optimization, and innovation-driven competitiveness. In contrast, SM shows a weaker and marginal relationship with BP, suggesting that its benefits materialize more gradually through long-term processes of brand consolidation, customer engagement, and stakeholder trust.

This distinction reinforces the idea that sustainability strategies differ not only in scope but also in the temporality of their outcomes. CE and EI deliver tangible short-term results by transforming production systems and technologies, whereas SM represents a relational and perception-based capability that requires time to translate into measurable performance improvements. Such temporal differentiation helps explain why MSMEs—often constrained by limited resources and short-term objectives—prioritize CE and EI initiatives over marketing-based strategies, even when the latter can strengthen resilience and market positioning in the long run.

5.2. Implications

The findings of this study provide relevant implications for theory and context. From a theoretical perspective, the results reinforce previous evidence positioning CE as a systemic paradigm that enhances firm performance through improved resource efficiency and circular production systems [

4,

13]. The significant influence of CE on both EI and BP supports the argument that circular strategies not only optimize material flows but also foster innovation-oriented learning processes that strengthen competitiveness in MSMEs [

5,

17]. Similarly, the positive relationship between EI and BP confirms that eco-innovation remains a key mechanism linking environmental performance and economic outcomes, consistent with the findings of Demirel and Kesidou [

16] and Janahi et al. [

15].

In contrast, the marginal effect of SM on BP diverges from results observed in studies conducted in developed markets [

21,

22]. This difference may stem from contextual and temporal factors. From a contextual perspective, MSMEs in emerging economies face resource limitations, limited sustainability awareness, and weaker institutional pressures, which constrain the immediate effect of marketing-based sustainability strategies [

10,

20]. From a temporal perspective, SM may generate its greatest impact over time, as it involves cumulative processes of brand development, customer engagement, and stakeholder trust—dimensions that require longer time horizons to translate into measurable business performance.

While the sample is geographically limited to the state of Aguascalientes, this region represents a typical industrial cluster within Mexico’s emerging economy, characterized by a strong manufacturing base, a high concentration of MSMEs, and growing integration into global supply chains. These features reflect conditions common to many emerging economies, where industrial dynamism coexists with financial, technological, and institutional constraints. The analytic generalization achieved in this study rests on a statistically rigorous sampling design that ensures representativeness within the target population while providing theoretical transferability to comparable contexts where similar institutional and resource conditions shape sustainability adoption [

33].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides valuable insights into the relationships among CE, EI, SM, and BP in MSMEs, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research focuses on a single region—Aguascalientes, Mexico—whose characteristics, while typical of emerging economies, may limit the generalization of the findings to other geographical contexts. Future research should replicate this model in different industrial clusters and countries to assess its applicability across diverse institutional and cultural settings.

Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data restricts the ability to capture the temporal dynamics of sustainability strategies. Longitudinal designs would allow researchers to observe how the effects of CE, EI, and particularly SM evolve over time, potentially confirming the delayed impact of SM on BP suggested by this study.

Third, the model focuses on internal firm-level factors and does not explicitly incorporate external influences such as regulatory frameworks, market turbulence, or technological change. Future studies could extend the model by including moderating or mediating variables—such as institutional pressures, environmental uncertainty, or digital maturity—to better understand the boundary conditions of sustainability-driven performance.

Finally, expanding the dataset to include qualitative evidence, such as interviews or case studies, could enrich the understanding of how firms perceive and operationalize sustainability practices. Such mixed-methods approaches would strengthen the explanatory and predictive capacity of future research in this field.

6. Conclusions and Strategic Implications

The findings highlight that integrating sustainability into business strategies not only supports environmental stewardship but also enhances organizational performance and stakeholder engagement. Although each sustainability strategy demands different levels of resources and commitment, even incremental actions can yield tangible benefits such as greater efficiency, stronger brand trust, and more resilient organizational culture.

For MSMEs, the results confirm that CE and EI represent the most effective short-term strategies to improve BP and resilience. Accordingly, firms should prioritize initiatives that enhance resource efficiency, reduce waste, and embed eco-innovation into production and process design. These actions can deliver faster and more visible outcomes, consolidating competitiveness while advancing sustainability.

Based on these findings, strategic recommendations are proposed for the wholesale trade and food and beverage service sectors in Aguascalientes. In wholesale trade, it is essential to adopt circular logistics and traceability systems that enable packaging recovery, optimize transportation routes, and leverage digital platforms for efficiency and transparency. Complementarily, responsible marketing campaigns should promote sustainable consumption and highlight products with lower environmental impact, while strategic alliances with manufacturers and retailers can help integrate sustainability criteria into supplier selection. In the food and beverage services sector, priority should be given to waste reduction and by-product utilization through practices such as composting or bioenergy generation, alongside the adoption of eco-technologies that improve energy and water efficiency. These measures can strengthen corporate reputation and consumer trust through certification programs and environmental standards.

Finally, business sustainability decisions rest on three fundamental pillars: goals, stakeholders, and capital [

23]. Goals encompass economic, environmental, and social objectives that seek to balance profitability, environmental care, and social well-being. Stakeholders—governments, organizations, and citizens—must interact in a coordinated manner to promote sustainable development. Capital comprises human, natural, financial, institutional, and technological resources, all of which are essential to sustaining a comprehensive and balanced sustainability model over time. Achieving equilibrium among these pillars ensures that sustainability efforts are both strategic and enduring.