1. Introduction

Bridging science, culture and sustainability, astrotourism emerges as a practice capable of simultaneously addressing global challenges—such as light pollution—and local demands for community cohesion and inclusive development. The night sky, regarded as a common heritage of humankind, has in recent decades been reframed as a strategic resource for sustainable development. Astrotourism, understood as a form of special interest tourism, values stargazing and the natural and cultural heritage associated with the astronomical experience, combining naked-eye observation, educational activities, cultural events, and local knowledge [

1,

2,

3]. Its relevance extends beyond leisure: by encouraging light pollution reduction, it contributes to environmental conservation [

4,

5]; by diversifying activities in rural and low-density areas, it expands livelihood opportunities and reinforces community identities [

6,

7]. In Portugal, for instance, the Dark Sky Alqueva certification transformed a low-density territory into an international reference, generating employment and global visibility [

8].

Although stargazing is an age-old practice, the consolidation of the term astrotourism is recent, having expanded in the past two decades with the rise of Dark Sky certifications, public policies, and strengthened debates on light pollution [

9,

10]. In 2024 alone, nearly 30 new sites were certified, bringing the global total to around 250 recognized areas [

11]. This expansion reflects the emergence of international networks dedicated to dark-sky preservation while creating new economic, cultural, and educational opportunities. In summary, astrotourism has rapidly evolved into a global phenomenon with significant environmental, cultural, and economic implications.

Despite such progress, the social potential of astrotourism remains underexplored. The literature has primarily highlighted environmental and economic impacts [

12,

13], devoting less attention to its ability to foster productive inclusion, strengthen social capital, and enhance community cohesion—dimensions central to territorial social innovation [

14,

15,

16]. This study seeks to address this gap, approaching astrotourism as fertile ground for social innovation by linking local practices to broader institutional scales. This confirms the need to reposition astrotourism within broader debates on territorial social innovation. The core assumption is that, when guided by socially innovative practices, astrotourism can transform peripheral territories into living laboratories of sustainable development while offering strategic references for inclusive public policies.

Previous research has already linked sustainable tourism to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

17,

18] and documented cases in which astrotourism directly contributes to global targets, such as in Namibia [

19]. Yet most analyses have privileged environmental metrics or marketing approaches, without adequately exploring how community practices connect with public policies and governance models. It is within this gap that the present paper positions itself, advancing a comparative interpretative framework capable of revealing patterns and specificities.

By engaging with SDGs 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), 4 (Quality Education), and 10 (Reduced Inequalities), this research emphasizes peripheral contexts—small municipalities, rural areas, and regions of lower economic density in both the Global South and developed countries—where the night sky can be activated as common heritage and as a driver of inclusive development. In particular, SDG 10 is operationalised through place-based capability building, inclusive governance arrangements, and local value-capture mechanisms that mitigate territorial disparities in peripheral contexts.

The originality of this study lies in the comparative analysis of four international experiences—Chile, Portugal, Canada, and South Africa—operating across distinct governance scales (from micro to macro). Case selection was guided by three criteria: social relevance, geographical diversity, and availability of reliable sources. Ultimately, the findings provide insights for public policy, governance strategies, and replicable models of sustainable astrotourism, broadening dialogue among science, communities, and decision-makers.

2. Theoretical Framework

Astrotourism is a practice that intertwines science, culture, environment, and economy. To capture its multi-dimensional impacts, we adopt a social innovation perspective that addresses collective and territorial transformations beyond purely technical or economic views. This choice is grounded in recent scholarship that moves beyond technocentric, efficiency-driven models of innovation toward frameworks centred on sustainability, public value, and territorial transformation [

19,

20,

21] and aligns with mission-oriented approaches that link grand challenges (e.g., energy transition, environmental justice) to place-based capabilities [

22,

23]. In peripheral contexts, these transformations involve environmental preservation, community strengthening, socio-economic inclusion, and cultural valorisation.

We therefore hypothesise that the night sky, recognised as a common good, can be activated through astrotourism to generate public value at multiple scales. Accordingly, the framework is organised into four thematic blocks: (i) social innovation and territorial development in peripheral contexts; (ii) astrotourism as a multi-faceted practice; (iii) light pollution as a socio-environmental issue; and (iv) interfaces with the United Nation (UN) 2030 Agenda [

24]. Three transversal axes underpin this discussion—citizen participation [

25,

26], the commons [

27,

28], and Brazilian social technologies [

29,

30]—articulated with the ecology of knowledges [

31] and relational territorial ecologies [

32,

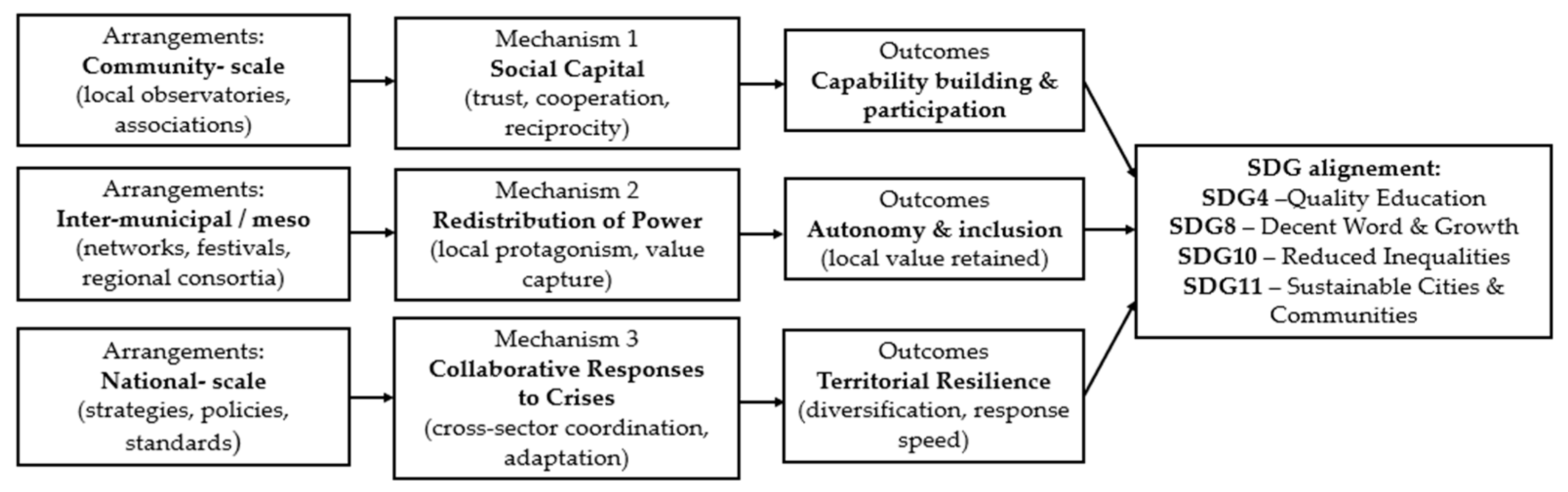

33]. The study aims to interpret, in comparative perspective, how astrotourism activates dimensions of social innovation across different territorial contexts by analysing four international cases (Chile, Portugal, Canada, South Africa), using secondary documentary and bibliographic sources and a three-dimensional analytical matrix (social capital, redistribution of power, collaborative responses to crises). Because the study relies exclusively on secondary materials, constructs such as trust/social capital are treated as interpretive inferences rather than measured variables, and primary data collection lies outside the scope of this article (see Limitations).

2.1. Social Innovation and Territorial Development in Peripheral Contexts

Recent scholarship documents a move beyond technocentric innovation—centred on efficiency and competitiveness—towards approaches stressing sustainability, public value, and territorial transformation [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Mission-oriented policies embody this shift by linking grand challenges (energy transition, environmental justice) to locally grounded strategies. In peripheral regions, astrotourism consolidates when global aspirations are anchored in territorial realities, where science, culture, and community resources intersect to generate inclusive development. In this horizon, social innovation is pivotal: more than technical advances, it entails collective solutions capable of transforming practices and producing lasting impacts amid material constraints and symbolic challenges (identity, belonging) [

31,

34].

Three dimensions structure the analysis: social capital, redistribution of power, and collaborative responses to crises:

- 1

Social capital—Associated with the quality of trust networks, cooperation, and reciprocity that sustain collective action [

35,

36]. Moulaert et al. [

34] emphasize that, without trust-based ties, social innovation rarely takes root in territories. In astrotourism, this dimension manifests in the creation of community associations, the engagement of residents as guides and hosts, and partnerships with observatories and universities. Experiences such as Alfa Aldea (Chile) or rural communities certified as Dark Sky Places illustrate how local networks are decisive for consolidating the activity.

- 2

Redistribution of power—Refers to the strengthening of community protagonism and the appropriation of social and economic benefits. Moulaert & Nussbaumer [

14] argue that, in peripheral contexts, social innovation only consolidates when it promotes real shifts of power, enabling local groups to move beyond being passive recipients. Cajaiba-Santana [

19] adds that social innovation implies institutional changes that transform power structures. In astrotourism, this occurs when communities manage observatories, festivals, or tourism routes, setting their own rules. South Africa’s National Astrotourism Strategy exemplifies this by prioritizing women and rural youth in leadership roles.

- 3

Collaborative responses to crises—Concerns the capacity for creative mobilization of internal and external actors in the face of structural deficiencies or situations of vulnerability. Neumeier [

15] shows that, particularly in rural areas, social innovation often emerges as a reaction to crises, when traditional institutions fail to provide adequate responses. Pereira & Bittencourt [

37] further stress that, in contemporary contexts of uncertainty, cross-sectoral arrangements become fundamental for sustaining innovative activities. In astrotourism, this dimension appears in initiatives that bring together universities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local governments to address issues such as light pollution or lack of infrastructure. Cases like the Jasper Dark Sky Festival (Canada) or training programs in Kenya highlight how multiscale alliances sustain the activity.

Taken together, these three dimensions provide a flexible interpretive matrix for observing how astrotourism activates commons, expands territorial capabilities, and advances SDG-aligned outcomes—especially SDGs 4, 8, 10, and 11.

This core framework connects with complementary references: citizen participation as a continuum from consultation to co-production [

25,

26]; intangible commons, whose preservation requires collective agreements [

28]; and territorial governance, which articulates multiple actors and scales [

38]. In this perspective, the territory should be seen as a relational ecology [

32,

33], aligned with the concept of the pluriverse [

39], which recognizes the coexistence of diverse rationalities. In astrotourism, this means acknowledging that the night sky can be simultaneously a scientific object, a tourism resource, and a cultural heritage of local communities.

In applied terms, this perspective translates into social technologies—developed in Brazil [

29]—that politicize the innovation process by incorporating community protagonism [

30]. Carniello & Santos [

40] emphasize that, when conceived participatorily, these technologies enhance the capacity of territories to address socio-environmental challenges. In astrotourism, this includes initiatives ranging from astronomy workshops in rural schools to tourism routes based on indigenous constellational narratives, exemplifying a true ecology of knowledges [

31].

Table 1 condenses the three dimensions into operational signals, expected outcomes, and example indicators, making the relationships explicit for later cross-case comparison.

The table above translates the three dimensions into observable signals in the documents and into mid-term outcomes relevant to peripheral territories. The example indicators are illustrative (not exhaustive) and are intended to guide future primary data collection and monitoring. The criteria for selection and the coding procedures used to derive these signals are detailed in the Methodology (

Section 3).

Thus, territorialized social innovation demonstrates that astrotourism is not merely an economic or cultural strategy, but a fertile field for activating commons, strengthening local ties, and inaugurating new forms of governance. It is on this basis that its concepts, scope, and potentialities are understood, as discussed in the next subsection.

2.2. Astrotourism: Concepts, Practices, and Social Innovation Potential

Astrotourism is a form of special-interest tourism based on the observation of the night sky and the valorisation of natural and cultural heritage associated with the astronomical experience [

1,

2]. Its hybrid nature—scientific, environmental, cultural, and recreational—allows it to engage diverse audiences, generating both contemplative and educational experiences as well as strategies for territorial development. Analysed through the lens of social innovation, three premises guide this study: (i) the night sky is an intangible common good whose preservation requires collective governance; (ii) the sustainability of the activity depends on community protagonism and the integration of plural knowledges; and (iii) international evidence indicates synergistic environmental, cultural, and economic benefits that strengthen territorial capacities.

Although sky observation is millennial, the term “astrotourism” has consolidated only in the last two decades [

16], driven by: (i) Dark Sky certifications that established technical and symbolic standards of protection; (ii) the recognition of light pollution as an environmental, cultural, and public-health problem; and (iii) the inclusion of scientific–cultural tourism in conservation policies [

1,

11]. By 2024, nearly 250 Dark Sky Places existed worldwide [

11], ranging from national parks to rural communities and private initiatives [

6].

International examples reveal this potential: in Spain, diversified experiences increased demand for sky tourism by 400% [

41]; in Kenya, Leo Sky Africa combines astronomy with Samburu traditions [

42]; in New Zealand, the Kaikōura Dark Sky Sanctuary connects conservation and tourism [

43]; in India, the Dark Sky Conclave brings together science and community [

44]; in the United States, the Adirondacks have developed mobile planetariums [

45]; in Argentina, the search for southern auroras has attracted tourists and scientists [

46]; and in China, Xichong (Shenzhen) became the first International Dark Sky Community after lighting reforms and local mobilization [

47]. Across these cases, the key dimensions of social innovation already highlighted are evident: trust networks (social capital), activation of endogenous resources (redistribution of power), and shared solutions to collective challenges (collaborative responses).

International experiences across regions show consistent patterns along the three dimensions.

Figure 1 summarises the interpreted linkages between these mechanisms and their associated mid-term outcomes, with illustrative case hints (see

Section 3 and

Section 3.7).

Across environmental, economic, cultural, and educational fronts, effects are interconnected: preservation of night skies and nocturnal ecosystems [

4]; productive diversification and support for micro-enterprises [

6]; valorisation of traditional cosmologies [

48]; and closer links between science and society [

49]. In peripheral contexts often rendered invisible by urban centralities [

50], astrotourism can re-signify preserved skies as ecological, cultural, and economic assets. By activating existing resources, it counters extractivist models and strengthens endogenous development, aligning with SDGs 4, 8, 10, and 11.

This approach converges with the “ecology of knowledges” [

31], which promotes dialogue between science, techniques, and local cosmologies. In practice, initiatives such as school workshops, routes based on indigenous star narratives, and public sky events turn the sky into a symbolic interface between science and culture. Unlike resources that require transformation, the sky is a universal heritage already present; its activation, however, depends on institutional recognition and multi-scalar governance.

Finally, consolidation requires addressing structural threats, especially light pollution—a global socio-environmental issue whose impacts on biodiversity, health, and celestial cultures are discussed in the next subsection.

2.3. Light Pollution as a Socio-Environmental Issue

Light pollution—understood as the adverse alteration of natural nocturnal light levels caused by excessive, inappropriate, or poorly directed artificial emissions—has become a major challenge for preserving the night sky and sustaining nocturnal ecosystems [

4,

5]. It is a global, multi-scalar phenomenon intensified by urbanisation and industrialisation; its effects spread beyond cities to remote areas via atmospheric dispersion. In astrotourism, this is strategic: without effective lighting management, destinations quickly lose their core asset—the quality of the sky.

From the perspective of territorial social innovation, the night sky can be treated as an intangible common good [

28], difficult to exclude and collectively used. Its degradation echoes Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” [

27], whereas Ostrom [

28] shows that communities can design collaborative rules—grounded in trust and social norms—applicable to lighting regulation and sky protection.

Excessive lighting disrupts circadian rhythms and ecological behaviours, affecting food chains, migrations, and reproduction [

13]. These pressures are critical in places that combine nature tourism and conservation. In such contexts, response capacity is closely associated with social capital—trust networks and cooperation among communities, researchers, and environmental managers.

For human health, evidence links chronic night-time exposure to sleep disturbance, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular disease [

5]. Because impacts are uneven, mitigation also requires redistribution of power—ensuring that peripheral communities participate in lighting decisions and have access to information and adequate infrastructure.

Culturally, the loss of the starry sky erodes intangible heritage embedded in cosmologies, rituals, and narratives, diminishing both the educational and contemplative potential of astrotourism and the continuity of identities [

1]. Sustained cultural and tourism initiatives therefore depend on collaborative responses to crises, mobilising residents, educators, operators, and scientific institutions to restore sky visibility and reactivate symbolic meanings.

Economically, dark-sky destinations risk losing visitors and value chains. Yet responsible lighting policies can yield multiple benefits: mitigating environmental impacts, reducing energy costs, and strengthening a territory’s sustainable image [

13]. Flagstaff (USA)—the first International Dark Sky City—illustrates that community lighting standards, combined with citizen participation, can protect the sky while supporting local dynamism [

11].

Taken together, these strands indicate that light pollution is a complex socio-environmental issue requiring coordination among governments, communities, the private sector, and international organisations. Policies on responsible lighting, environmental education, and dark-sky certification align with SDGs 3 (Health and Well-Being), 10 (Reduced Inequalities), 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and 15 (Life on Land).

2.4. Astrotourism and the UN 2030 Agenda: Interfaces with the SDGs

Although astrotourism can be linked to a broad range of Sustainable Development Goals—as demonstrated by Dalgleish et al. [

18] in the Namibian case, highlighting impacts across fields from education to gender equality, from innovation to cultural preservation—this paper does not aim to exhaust this relationship. The analytical focus is narrowed to four SDGs most directly connected to the dimensions of territorial social innovation discussed in

Section 2.1: Quality Education (SDG 4), Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10), and Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11). This choice is justified not only by their recurrence in the international literature [

1,

2,

6,

50], but also by their practical relevance: these SDGs are central to guiding public policies, governance strategies, and community initiatives in peripheral territories.

In the field of Quality Education (SDG 4), astrotourism promotes scientific literacy and fosters interest in astronomy and environmental sciences, particularly in contexts with limited educational opportunities [

48]. Beyond formal instruction, it enables encounters between scientific knowledge and traditional wisdom, strengthening both learning processes and the preservation of local cosmologies. Community workshops in Chile and training programs in Namibia [

18] illustrate how the night sky can serve as a living laboratory for learning and territorial identity.

With regard to Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), astrotourism diversifies the productive base and reduces dependency on seasonal activities [

6]. In addition to direct employment, it stimulates short value chains in hospitality, transport, handicrafts, and local services. These benefits, however, only become sustainable when models prioritize community governance and avoid market capture by large operators. Experiences such as the integration of astrotourism into conservancies in Namibia confirm that economic sustainability depends on endogenous institutional arrangements [

18].

Concerning Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10), astrotourism can foster social inclusion and benefit redistribution, especially when structured around the protagonism of historically marginalized groups—youth, women, Indigenous peoples, and rural populations [

50]. Here, the dimension of power redistribution becomes central, enhancing autonomy and local participation. The valorization of Ju/’Hoansi starlore in Namibia exemplifies how astrotourism practices can recover endangered cultural heritage while strengthening community self-esteem [

18].

Finally, in SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) the connection is clear in the mitigation of light pollution and the promotion of responsible lighting policies [

4]. Such measures reinforce local identities, protect nocturnal ecosystems, and increase tourism attractiveness. The case of Xichong, China—recognized as the country’s first International Dark Sky Community—illustrates the convergence between community action and public policies to balance coastal tourism and sky protection, integrating conservation with regional development [

47].

To synthesize these interactions,

Table 2 systematizes the potential contributions of astrotourism to the four selected SDGs, highlighting fields of impact and example indicators. More than an academic synthesis, the table is presented as a practical tool, useful for guiding managers, communities, and policymakers in translating the SDGs into tangible territorial development strategies. At the same time, the highlighted examples should be understood as situated inspirations—not universal models, but experiences that demonstrate how astrotourism can be articulated across diverse socio-territorial contexts while preserving cultural and environmental specificities.

This table is intended as a practical guide for programmes and policies. Indicator selection should be co-defined with local stakeholders, include disaggregation (e.g., gender, age, territory), and specify baseline and periodicity. Where feasible, combine these indicators with primary methods (surveys, interviews, network analysis) to validate the interpretive pathways summarised in

Figure 2 and to track progress over time.

2.5. Concluding Remarks on the Theoretical Framework

The analysis developed throughout this section demonstrated that social innovation, astrotourism, light pollution, and the 2030 Agenda already have consolidated contributions in the literature, yet they are rarely addressed in an integrated manner. By bringing them together within a single framework, this study proposes a perspective that recognizes the night sky as a common good and astrotourism as a practice capable of articulating environmental preservation, cultural strengthening, economic dynamization, and social inclusion.

Each previous subsection contributed to this synthesis: (i) social innovation, particularly in peripheral contexts, highlights the importance of social capital, power redistribution, and community cooperation; (ii) astrotourism emerges as a hybrid modality that connects science, culture, and economy; (iii) light pollution is revealed as a transversal threat requiring collective governance; and (iv) the UN 2030 Agenda [

24] provides a global framework for translating these dimensions into public policies and local strategies.

This framework is not merely an analytical exercise but also points to practical applications: guiding responsible lighting policies, structuring inclusive territorial governance models, valorizing intangible heritage, and expanding opportunities in often marginalized territories. By emphasizing the articulation between global references and local specificities, the study offers an original contribution to understanding the role of astrotourism in promoting fairer and more sustainable forms of development.

Based on this theoretical apparatus, the following section presents the research methodology, detailing the analytical pathways and interpretative choices that guide the comparative analysis of international experiences.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative, exploratory, and interpretative multiple-case design grounded in documentary and bibliographic evidence. In line with Creswell [

51] and Flick [

52], the emphasis is on depth of meaning and context rather than statistical generalisation. We comparatively examine four international astrotourism initiatives—Alfa Aldea (Chile), Dark Sky Alqueva (Portugal), the Jasper Dark Sky Festival (Canada), and the National Astrotourism Strategy (South Africa)—and apply thematic content analysis and cross-case synthesis, guided by a three-dimensional analytical matrix (social capital; redistribution of power; collaborative responses to crises).

3.1. Research Subject

The research subject is the phenomenon of astrotourism as social innovation in peripheral territories under dark skies. The unit of analysis consists of four documented initiatives at different governance scales—Alfa Aldea (Chile), Dark Sky Alqueva (Portugal), Jasper Dark Sky Festival (Canada), and the National Astrotourism Strategy (South Africa). The spatial scope spans peripheral municipalities and regions in these four countries, and the temporal scope focuses on 2010–2025 to capture design, implementation, and consolidation phases. The level of analysis is multi-scalar (community, inter-municipal/meso, and national), and the evidentiary base is documentary/bibliographic rather than individual respondents.

3.2. Analytical Dimensions (Operationalisation)

The comparative reading was guided by three dimensions of social innovation identified in the literature:

Social capital—Linked to networks of trust, cooperation, and belonging that sustain collective action. Oberle [

36] and Putnam [

35] highlight how the quality of social relations enables collaboration and reciprocity. In astrotourism, this manifests in community associations, residents working as guides and hosts, and partnerships with observatories and universities.

Redistribution of power—Refers to the strengthening of local protagonism and the activation of endogenous resources. Moulaert & Nussbaumer [

14] stress that social innovation in peripheral contexts consolidates only when real shifts in power occur, enhancing community autonomy.

Collaborative response to crises—Concerns the creative mobilisation of actors and resources in the face of structural challenges. Neumeier [

15] shows that, particularly in rural areas, social innovation often arises as a collective response to crises or scarcity, generating context-adapted solutions.

In the documentary corpus, social capital was traced through convergent signals such as sustained partnerships, repeated multi-actor participation, third-party recognition, and continuity of citizen-science and volunteering programmes; redistribution of power, through community governance, shared decision-making, municipal instruments, and revenue-sharing; and collaborative responses to crises, through cross-sector arrangements, protocols/funds, and adaptive strategies to shocks (e.g., seasonality, wildfires, energy shortages).

3.3. Source Material (Selection and Inclusion Criteria)

Data collection was based exclusively on secondary sources: academic papers, institutional reports, official documents, and publicly available outreach materials. Sources were retrieved from national policy portals, municipal gazettes, official institutional websites, the IDA Dark Sky and UNESCO/UNWTO repositories, academic databases (e.g., Scopus/Google Scholar), and verified media archives. Priority was given to recent, consistent, and verifiable records, ensuring a solid empirical foundation for comparison.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria. We used publicly traceable materials (URL/DOI or institutional repository) with substantive relevance to at least one analytical dimension and cross-case comparability of information depth. Opinion pieces without documentary basis or untraceable items were excluded. Source types included policy documents, institutional reports, official websites, academic publications, grey literature, and media articles. Whenever possible, we sought triangulation across source types (e.g., policy document + institutional report + academic publication) to improve evidentiary robustness.

3.4. Case Selection (Justification)

Case selection justification. The selection of the four cases sought to ensure diversity of institutional scales, geographical contexts, and governance forms, thereby reinforcing the validity of the comparative analysis. Methodologically, we adopt a multiple-case study design and a comparative approach appropriate for complex socio-territorial phenomena [

53,

54]. Three criteria guided case selection:

Social relevance—each experience demonstrates concrete forms of productive inclusion, community cooperation, or identity strengthening in peripheral territories [

15,

34].

Institutional and geographical diversity—the sample includes community initiatives, inter-municipal networks, cultural events, and national public policies, distributed across South America, Europe, North America, and Africa.

Availability and reliability of sources—all cases are supported by sufficient academic, institutional, and publicly available documentation, ensuring empirical consistency and enabling critical analysis [

8,

55,

56,

57].

The adoption of these three criteria is justified by their complementarity. Social relevance guarantees that selected cases represent effective manifestations of social innovation, aligned with the analytical dimensions of the study. Institutional and geographical diversity enables the identification of patterns and contrasts across different scales and territorial contexts, avoiding over-generalisation and enriching the comparative approach. Finally, the availability and reliability of sources ensures methodological consistency, enabling critical interpretation even in a study based primarily on secondary data. Together, these criteria ensure that the sample is substantive, diverse, and methodologically robust.

Arrangements:

Alfa Aldea (Chile): a family-based community initiative that has become a vector of social cohesion and affective hospitality in a rural context.

Dark Sky Alqueva (Portugal): a pioneering inter-municipal consortium that institutionalised dark-sky certification as a central axis of regional policy.

Jasper Dark Sky Festival (Canada): a meso-scale event integrating science, culture, and tourism in a national park, engaging multiple actors through collaborative governance arrangements.

South Africa’s National Astrotourism Strategy: a nationwide public policy that consolidates astrotourism as a development strategy, with emphasis on productive inclusion and the valorisation of African cosmologies.

This diversity of formats and scales makes it possible to observe how the principles of social innovation—social capital, redistribution of power, and collaborative response to crises—materialise in different ways, while also revealing convergences such as cultural valorisation and the strengthening of trust networks. The first example, situated at the micro-scale, is Alfa Aldea in the Región Estrella (Chile), which demonstrates how a community initiative can transform the night sky into a collective heritage and a driver of territorial resilience.

3.5. Research Method Applied to the Source Material

Interpretation followed two complementary steps:

Content analysis [

58], aimed at identifying recurrent categories within the documents.

Thematic analysis [

59], used to interpret meanings and connections between social innovation, astrotourism, and territorial development.

Procedure. We organised the material by case, coded it along the three dimensions, triangulated across policy/institutional/academic/media sources to seek convergent signals and note discrepancies, and then built a cross-case comparative matrix to synthesise convergences and divergences by governance scale, institutional arrangements, and territorial conditions. Coding was deductive-guided by the three dimensions and open to emergent sub-codes; coding memos documented how specific textual passages mapped onto each construct. Where possible, claims were checked against at least two independent source types (e.g., policy + institutional report); discrepancies were noted and discussed as part of the interpretive synthesis.

Qualification of inferences. Given the exclusive reliance on secondary sources, statements regarding trust/social capital are presented as interpretive inferences from convergent documentary signals rather than measured constructs.

3.6. Comparative Procedure

The cases were organised into a comparative analytical matrix, where each social innovation dimension was cross-referenced with the four cases. This strategy allowed the identification of convergences (such as the centrality of trust and belonging) and specificities related to governance scale, institutional arrangements, and territorial conditions.

3.7. Limitations

The research relies exclusively on secondary data, without primary fieldwork. Its character is exploratory and interpretative, seeking to provide an initial analytical framework that can be further developed in future studies employing interviews, surveys, participant observation, and network analysis. Given the exclusive reliance on secondary sources, statements regarding trust/social capital are presented as interpretive inferences rather than measured constructs; consequently, generalisability is bounded and causal claims are not advanced. These limitations delimit the scope of the conclusions advanced in the Discussion.

4. Results

This section presents and analyzes four international cases of astrotourism, selected for their relevance to the social dimension. The approach combines contextual description and integrated analytical interpretation: in each case, after characterizing the territorial, historical, and institutional context, manifestations of three interdependent axes of social innovation are identified—social capital, redistribution of power, and collaborative response to crises—as defined by classical and contemporary literature on the topic [

14,

34,

60,

61,

62].

The analytical perspective adopted here understands social innovation as a process of transforming community ties and governance structures, linking the satisfaction of collective needs, the reconfiguration of social relations, and the strengthening of local autonomy [

34,

63]. This view recognizes that socially innovative actions often emerge when problems or opportunities cannot be adequately addressed by traditional institutional formats, thus requiring creative and collaborative arrangements among different actors and sectors [

37].

The presentation of results follows a governance-scale logic, showing how the principles of social innovation manifest at different levels: it begins with the community micro-scale (Alfa Aldea, Chile), advances to the regional scale (Dark Sky Alqueva, Portugal), includes the meso-scale of cultural events (Jasper Dark Sky Festival, Canada)—positioned between the local and the institutionalized levels, as it involves multiple actors and projects impacts beyond the immediate territory—and culminates at the national macro-scale (South Africa’s National Astrotourism Strategy). This progression highlights that social innovation in astrotourism is not restricted to a single institutional model, but can emerge through multiple arrangements, marked by convergences—such as cultural valorization and trust networks—as well as specificities related to the degree of institutionalization, territorial conditions, and crisis management strategies.

4.1. Alfa Aldea, Región Estrella—Chile (Micro-Scale)

The Coquimbo Region, promoted as Región Estrella (Star Region), has consolidated itself as an international hub of astrotourism due to its exceptional natural conditions—more than 300 clear nights per year, stable semi-arid climate, and low levels of light pollution. The total solar eclipse of July 2019 marked a turning point in international visibility, attracting around 300,000 visitors and generating US

$83 million in revenue, while also stimulating investments in infrastructure, training, and territorial promotion [

64]. Within this context, Alfa Aldea, a family-run initiative located in Vicuña, in the Elqui Valley, stands out as a community laboratory of social innovation. The project gained recognition by receiving the

Más Valor Turístico award in 2022, promoted by SERNATUR, in the category of accessible tourism, for implementing inclusive and sustainable practices [

65]. Local recognitions, such as the

Sello V granted by the municipality of Vicuña, further reinforced its community legitimacy and role as a reference in responsible tourism [

66].

Social Capital: Alfa Aldea strengthens networks of trust through affective hospitality and inclusive experiences that bridge science and ancestry. The Inclusive Astronomical Talks, highlighted by the national award, employ radio telescopes that convert cosmic signals into sound and 3D-printed tactile models, enabling visually impaired visitors to “hear” and “touch” the universe [

67]. This personalized mediation reinforces emotional bonds with the night sky and legitimizes local protagonism as host of the tourism experience. Moreover, intergenerational ties built with schools and cultural associations have helped consolidate a shared sense of belonging around the night sky.

Redistribution of Power: Redistribution of Power: Alfa Aldea operates under a fully community-driven model, ensuring that opportunities are redirected to guides, artisans, and small entrepreneurs in low-density territories [

65]. Local certification, such as the municipal Sello V, reinforces service quality and community autonomy [

66]. Nonetheless, challenges persist, including reliance on voluntarism and the risk that external tourism pressures may undermine local governance.

Collaborative Response to Crises: Alfa Aldea also exemplifies territorial resilience. In response to agricultural vulnerability and tourism seasonality, it developed partnerships with wineries, artisans, and schools to diversify tourism packages and maintain visitor flow throughout the year. Furthermore, it participates in regional initiatives, such as the strategic alliance between Vicuña and Paihuano for the joint promotion of the Elqui Valley as a sustainable astrotourism destination, aimed at overcoming dependency on seasonal events and consolidating tourism as a pillar of local development [

68]. However, the absence of structured public policies to provide financial support for small enterprises, combined with vulnerability to environmental crises—such as droughts and wildfires—exposes limits to long-term sustainability.

Interpretive Synthesis: The case of Alfa Aldea demonstrates how community-scale astrotourism can operate as a vector of territorially embedded social innovation. In Vicuña, the night sky has shifted from being merely a natural resource to becoming a collective heritage capable of fostering inclusive hospitality, redistributing economic opportunities, and mobilizing collaborative responses to local vulnerabilities. More than a tourism enterprise, Alfa Aldea functions as symbolic and relational infrastructure, activating networks of trust and positioning the Elqui Valley as an international reference in sustainable and accessible tourism. This community-led protagonism is part of a broader international recognition of Chilean astrotourism, recently highlighted by Hernández and León [

69] as a paradigmatic example of territorial innovation in tourism and hospitality.

If in Chile social innovation manifests at the community scale, rooted in local trust networks, in Portugal—as discussed in the following section—it unfolds at the regional scale, through an inter-municipal consortium that institutionalized astrotourism as an integrated territorial policy: Dark Sky Alqueva.

4.2. Dark Sky Alqueva—Portugal (Regional Scale)

Created in 2007 as the first territory certified by the Fundación Starlight, Dark Sky Alqueva has consolidated itself as a global reference by institutionalizing astrotourism at a regional scale [

8]. The certification, supported by UNESCO and UNWTO, established astronomical and environmental quality standards that positioned the night sky as a common heritage and a strategic resource for sustainable development. Spanning more than 10,000 km

2 and bringing together 11 Portuguese municipalities and adjacent Spanish areas, the project emerged as a response to the risk of tourism massification following the construction of Lake Alqueva. Its cooperative governance, led by the Dark Sky Foundation, integrates municipalities, tourism operators, universities, and NGOs, forming a resilient network—though not without tensions between global standardization and cultural diversity. Internationally awarded, this arrangement transformed astrotourism into a structuring axis of territorial policies in Alentejo. In 2021, the project received the Europe’s Responsible Tourism Award at the World Travel Awards, further strengthening its image as a socially and environmentally innovative and responsible tourism destination [

70].

Social Capital. The inter-municipal network and citizen science programs strengthened ties between local and regional actors, fostering trust and cooperation among institutions, residents, and visitors. Activities such as astrophotography workshops, night observation trails, and educational campaigns multiplied opportunities for rural communities, consolidating the night sky as a cultural and educational asset [

71]. At the same time, reliance on international certifications and labels can generate tensions, especially when global standards override local cultural practices.

Redistribution of Power. By involving small municipalities and local entrepreneurs in governance, the model reduced the centrality of major cities and redirected opportunities to low-density territories. The Dark Sky brand has integrated guides, artisans, and wine producers into the astrotourism economy, thereby expanding regional autonomy. More recently, the expansion of the Dark Sky Portugal network to destinations such as Aldeias do Xisto and Vale do Tua reinforced this decentralizing effect, broadening the territorial base for productive inclusion [

72,

73]. Nevertheless, some studies warn of the risk of benefit concentration among better-structured actors, requiring additional equity mechanisms across participating municipalities.

Collaborative Response to Crises. The project originated as an alternative to the risk of tourism massification brought by Lake Alqueva, re-signifying the territory through an intangible asset. During the pandemic, it adopted different response scenarios (Grade One, Two, and Three), ensuring the continuity of activities, maintaining community engagement, and prioritizing sensitive communication, including through astrophotography campaigns [

73]. This adaptive capacity preserved local jobs, encouraged solidarity, and reinforced territorial resilience amid uncertainty. However, heavy dependence on international tourism poses a long-term challenge, as global crises may directly affect the economic sustainability of the destination.

Interpretive Synthesis. Dark Sky Alqueva exemplifies how astrotourism can be institutionalized at a regional scale, transforming the night sky into a device of territorial regeneration. Notably, in 2024 Dark Sky Alqueva won the World Travel Awards’ Responsible Tourism (global) prize, recognizing its balance between tourism development and environmental preservation—further consolidating the destination’s leadership in sustainable astrotourism [

74]. Its strength lies not only in its pioneering certification but also in its ability to mobilize social capital, through cooperative networks and citizen science; re-distribute power, by decentralizing opportunities to low-density municipalities; and foster collaborative responses to crises, ensuring resilience in adverse scenarios. By integrating cooperative governance, cultural valorization, and productive inclusion, the project consolidates astrotourism as an innovative territorial policy, projecting Alentejo—and, by extension, Portugal—as a European reference in sustainable tourism.

4.3. Jasper Dark Sky Festival—Canada (Meso-Scale)

Unlike the Portuguese case, in which social innovation becomes institutionalized at a regional scale through inter-municipal consortia, in Canada it manifests in a cultural and festive format: the Jasper Dark Sky Festival (JDSF), held annually in Jasper National Park, Alberta. Created in 2011 to celebrate the park’s designation as a Dark Sky Preserve by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the festival has become one of the world’s most recognized astrotourism events. Initially conceived to stimulate tourism during the low season, it has consolidated itself as a catalyst for social inclusion, cultural valorization, and collective learning. According to a University of Alberta study, its success is linked to the capacity to mobilize community buy-in and empower local champions—individuals who understand the community’s social dynamics and lead initiatives collaboratively, bridging local interests with festival goals [

75].

Social Capital. The festival’s strength lies in its community embeddedness, sustained by trust-based relationships and the active role of local leadership. Betkowski [

75] and Shokeir [

76] emphasize that using community spaces—rather than external infrastructures—and combining science with infotainment reinforce a sense of belonging. Complementarily, Betkowski [

75] reports high satisfaction and learning outcomes that deepen visitor–resident ties, while Hayes [

77] highlights the engagement of multiple stakeholders (e.g., the Royal Astronomical Society and TELUS World of Science), expanding collaborative networks. The official 2025 program [

78] further illustrates this dimension by including free, open-access activities such as concerts, outdoor cinema, and ScienceFest, connecting science, culture, and society. Empirical research reinforces these findings: visitors to the JDSF report very high satisfaction levels, largely due to the diversity of events, welcoming community, and low costs, while also highlighting learning outcomes related to astronomy and nocturnal wildlife [

78]. Yet, the challenge remains of broadening inclusivity to underrepresented social groups, ensuring that community mobilization is genuinely equitable.

Redistribution of Power. While Tourism Jasper leads the festival’s governance, decision-making integrates multiple local actors. Betkowski [

75] points to the involvement of Indigenous communities and local curation as mechanisms ensuring that economic and cultural benefits remain within the territory. Shokeir [

76] observes that balancing scientific talks with cultural attractions broadens opportunities for artists and local entrepreneurs. Hayes [

77], however, warns that further adjustments in management and organizational behavior are needed to align the event more closely with dark-sky conservation goals. The 2025 edition sought to reinforce redistribution by launching the Dark Sky Package, integrating lodging, food, and experiences offered by community operators, ensuring that a significant share of revenue flowed back into the local economy. Survey results, however, indicate that most participants are urban-based, middle-aged visitors who travel considerable distances to attend (average 430 km) [

78], raising questions about the extent to which festival benefits and participation are equitably distributed among local communities. Still, the growing international visibility increases pressure from external operators, potentially undermining community autonomy.

Collaborative Response to Crises. The festival demonstrated resilience in facing COVID-19 restrictions and the impacts of wildfires. Betkowski [

75] reports that the response included planned cost reductions, free events, and a downscaled format to maintain community participation. Shokeir [

76] stresses the strategic choice of October, outside the high season, as a way to stimulate the local economy and mitigate seasonal vulnerabilities. Hvenegaard & Banack [

78] show that while 42% of visitors expressed willingness to adopt dark-sky protection practices, the translation of awareness into concrete conservation actions remains limited. Hayes [

77] corroborates this intention–action gap: although attitudes toward protecting dark skies are overwhelmingly positive, fewer than half of visitors plan to modify their behaviours. In 2025, programme diversification—including mountaintop observations on Whistlers Mountain, drone shows, and indoor activities—aimed to attract new audiences, reduce weather-related risks, and strengthen the event’s resilience. These efforts highlight the need for continuous strategies to balance conservation, tourism, and community engagement.

Interpretive Synthesis. The Jasper Dark Sky Festival demonstrates how astrotourism, at a meso-scale, can consolidate itself as a platform of social innovation by integrating science, culture, and community into an international event. Its relevance lies not only in attracting visitors but in its capacity to strengthen social capital—mobilizing trust and local leadership; redistribute power—by including entrepreneurs, artists, and Indigenous peoples in governance and benefits; and stimulate collaborative responses to crises—adapting to challenges such as pandemics, wildfires, and seasonality. More than a tourism product, the festival functions as a device of collective learning and identity reinforcement, though the challenge persists of converting environmental awareness into concrete conservation practices.

4.4. National Astro-Tourism Strategy—South Africa (Macro-Scale)

South Africa has established itself as a reference in the Global South by launching the National Astro-Tourism Strategy and Implementation Plan (2023–2033), approved by Cabinet in May 2025 and presented to Parliament after an extensive public consultation process. The symbolic launch took place in Carnarvon, on World Tourism Day (27 September 2024), in partnership between the Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation [

79]. This is the first national astro-tourism strategy on the African continent, articulating science, tourism, and social inclusion in a multi-scalar and cross-sectoral approach. The strategic document [

56] defines as its vision the positioning of South Africa as a global leader in astrotourism, integrating science, culture, and sustainable tourism. Its mission is to create inclusive economic opportunities, protect the night sky, and foster cultural and scientific exchange. Among the strategic pillars, the following stand out:

- (i)

Socioeconomic inclusion and capacity building for young people and women in rural communities;

- (ii)

Development of authentic tourism products that combine astronomy, local culture, and the environment;

- (iii)

Investment in infrastructure and marketing to create national astro-tourism routes and support community-based micro-enterprises.

The strategy identifies priority zones such as the Northern Cape (SALT and SKA), the Free State, and the Eastern Cape, encouraging the creation of internationally recognized Dark Sky Reserves. It also sets indicators and targets for 2033, including doubling the participation of local communities in the sector, expanding protected night-sky areas by 50%, and certifying a significant number of guides and community-based enterprises.

Social Capital. Programs such as the Astro-Tourism Enterprise Development and the Starlore Heritage Project build trust networks among scientists, local entrepreneurs, schools, and community guides. In the Karoo, six young people from Carnarvon and Vanwyksvlei—previously unemployed—were selected for an immersive training program covering business management, astronomy, telescope maintenance, storytelling, first aid, and tourism guiding. In Sutherland, where the SALT attracts around 13,000 visitors per year [

80], partnerships between the observatory, private operators, and community guides resulted in greater social integration and valorization of African starlore, strengthening cultural belonging and creating intergenerational bridges [

56,

80,

81].

Redistribution of Power. The strategy prioritizes the productive inclusion of youth and women, ensuring that local communities manage their own tourism enterprises. In the Karoo, participants of the SARAO program became micro-entrepreneurs, offering experiences that combine astronomical observation with traditional narratives of the !Xam (San) and Xhosa peoples, as well as routes along the Karoo Heritage Trail and traditional cart rides. In Sutherland, local guides play a central role in visitor services, transforming sky access into a community-driven product and reducing dependence on large external operators [

80]. According to Wassenaar and Coetzee [

81], the adoption of a polycentric governance model—bringing together local governments, the private sector, scientific institutions, and communities—is fundamental to redistribute power and ensure genuine participation in strategic decisions [

56,

82].

Collaborative Response to Crises. In areas marked by structural unemployment and rural exodus, astrotourism has served as an adaptive strategy to diversify the economy. In the Karoo, the SARAO program provided daily stipends to participants during training, ensuring immediate financial security, and prepared them to meet future demand from the SKA Carnarvon Exploratorium, designed as the region’s largest scientific tourism hub. In Sutherland, according to Jacobs, Du Preez, and Fairer-Wessels [

80], astrotourism stimulated improvements in community infrastructure and created new direct and indirect jobs, although challenges persist, such as reliance on a single attraction and the need to diversify tourism products to counteract seasonality. The creation of Astronomy Advantage Areas, protected against light and radiofrequency pollution, is interpreted by Wassenaar and Coetzee [

81] not only as a conservation action but also as a tool for territorial identity and sustainable investment attraction [

81,

82].

Interpretive synthesis. As the strategy is still under early implementation, its long-term impacts remain to be fully assessed. The South African case illustrates how astrotourism can be institutionalized as a national strategy of social innovation, integrating cutting-edge science, local cosmologies, and productive inclusion in peripheral territories. Its strength lies in the combination of social capital, built through trust networks and training programs; redistribution of power, by prioritizing youth, women, and rural communities in enterprise management; and collaborative responses to crises, creating alternatives to structural unemployment and rural exodus. Unlike community-based arrangements (Chile), regional consortia (Portugal), or festival formats (Canada), South Africa projects astrotourism as an integrated public policy, with a long-term vision and measurable targets, consolidating it as an instrument of social, cultural, and economic transformation on a continental scale.

5. Discussions

Across four distinct territorial contexts and governance scales the cases converge in showing astrotourism as a driver of social innovation via three interdependent mechanisms: strengthening trust-based networks, expanding community autonomy and value capture, and coordinating collaborative responses to structural challenges. The diversity of arrangements indicates that social innovation is less a property of a given model than a relational, situated, and adaptive process [

82,

83].

In Chile, community leadership is embodied in a family-based initiative that, through affective hospitality and inclusivity, became a regional reference point. In Portugal, an inter-municipal consortium institutionalized astrotourism as an integrated territorial policy, combining citizen science, decentralized economic opportunities, and resilience to crises. In Canada, an annual festival mobilizes multiple actors around a collective celebration of the night sky, turning science and culture into a platform for community learning. In South Africa, a national public policy establishes long-term goals, articulating cutting-edge science, local cosmologies, and productive inclusion as a strategy of territorial transformation at a continental scale.

To make convergences and context-specific variations explicit across governance scales,

Table 3 synthesises the four cases along the three analytical dimensions (social capital; redistribution of power; collaborative responses to crises).

Cross-case interpretive synthesis. By scale, mechanisms materialise differently: community formats (Chile) leverage intimate networks and affective hospitality; inter-municipal arrangements (Portugal) formalise cooperation and distribute benefits regionally; meso-scale events (Canada) mobilise broad coalitions but need to translate awareness into conservation behaviours; national policy (South Africa) provides enabling instruments and measurable targets. These are interpreted patterns from secondary documentation and do not imply causality; see Methodology and Limitations for inference bounds and validation avenues.

Regardless of scale—from a family-based initiative in Chile to a nationwide strategy in South Africa—astrotourism becomes socially innovative when the three mechanisms operate together: social capital (trust networks, intergenerational bonds, collective identity), redistribution of power (community management, productive inclusion, local protagonism), and collaborative responses to crises (adaptive capacity, diversification, coordinated action). Rather than mutually exclusive models, the arrangements form an ecology of scales in which different governance forms coexist, reinforce one another, and broaden the sector’s capacity for impact.

The comparative reading therefore suggests that preserving and valorising the night sky becomes a vector of territorial development only when linked to inclusion, cooperation, and resilience strategies. For policymakers, the lesson is clear: multi-scalar designs that value grassroots initiatives while articulating them with regional and national frameworks can convert local trust networks and cultural specificities into strategic assets for sustainable development. Astrotourism is thus best understood not as a single model, but as a mosaic of practices adapted to diverse socio-territorial contexts.

Limitation: This study relies exclusively on secondary documentation; findings are interpretive rather than causal and generalisability is bounded by scale, governance, and territorial conditions. Signals of trust/social capital and participation are inferred from convergent documents; despite triangulation across policy, institutional, academic, and media sources, residual coverage/reporting biases may remain. See Conclusion for avenues of empirical validation.

6. Conclusions

The comparative analysis of the four cases—Alfa Aldea in Región Estrella (Chile), Dark Sky Alqueva (Portugal), the Jasper Dark Sky Festival (Canada), and the National Astro-Tourism Strategy (South Africa)—demonstrates that when conceived and implemented in an integrated manner, astrotourism transcends its touristic dimension and consolidates itself as a vector of social innovation. Across different scales and institutional arrangements, recurrent manifestations of the three proposed analytical dimensions were identified:

- (i)

Social capital, sustained by trust networks, intergenerational bonds, and cooperation among actors;

- (ii)

Redistribution of power, associated with community management, productive inclusion, and local protagonism;

- (iii)

Collaborative responses to crises, expressed in economic diversification, territorial resilience, and adaptive capacity in the face of structural challenges [

14,

15,

18].

One of the main advances of this study lies in showing that these dimensions are not exclusive to a particular scale or governance model. On the contrary, they can emerge at different levels of organization—from community-based micro-scales to national macro-level strategies—and even coexist within the same territory. A country may, for instance, host simultaneously community initiatives, regional consortia, meso-scale festivals, and national strategies, composing an “ecology of scales” that enhances the sector’s potential impact and resilience. This reinforces that there is no single formula: each territory can articulate multiple arrangements adapted to its sociocultural and institutional conditions.

The central contribution of this paper is the proposal of an original interpretive matrix that reveals how socially innovative practices emerge across diverse governance arrangements and multiple scales, offering a framework for both academic analysis and practical application.

In the four cases analysed, the core mechanisms we identify—social capital, redistribution of power, and collaborative responses to crises—materialise in ways that are directly legible to SDG targets: (i) SDG 4 via astronomy-guided learning, teacher training, and community science programs; (ii) SDG 8 via the creation and strengthening of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs/SMEs), local procurement, and professional certification for guides; (iii) SDG 10 via the inclusion of women, youth, and indigenous or rural communities in revenue-sharing and governance; and (iv) SDG 11 via dark-sky criteria embedded in planning, lighting ordinances, and heritage/landscape protection. These contributions appear across scales—from community initiatives to national strategies—supporting a coherent, multi-scalar policy approach.

For policymakers, the findings of this study provide a scalable framework for leveraging astrotourism as a driver of social innovation. The proposed approach is grounded in the empirical observation that significant impact arises from the interaction of three core mechanisms: social capital, redistribution of power, and collaborative responses to crises. This necessitates coordinated action across different tiers of governance, with distinct yet complementary roles.

At the national level, the primary role is to establish enabling conditions. This recommendation is derived from the analysis of larger-scale, successful initiatives, which highlight the importance of foundational policy. Key actions should include formulating national dark sky protection standards, fostering cross-ministerial alignment, and deploying financial instruments such as tax incentives for compliant retrofits. Furthermore, creating frameworks for capability building, including certification programs for guides and educators, is essential for professionalizing the sector.

The regional and local level is critical for contextualized implementation and the materialization of social capital and redistributive effects. Here, policy should focus on forming inter-municipal consortia to coordinate offerings and share protocols, embedding dark sky criteria into local planning regulations, and implementing measures for inclusive value capture. The latter can be achieved through local procurement clauses and support for community-based enterprises, ensuring that economic benefits are retained within the local territory.

To ensure the sustained impact and resilience of these initiatives, a cross-cutting focus on monitoring and learning is indispensable. We recommend implementing a lean management dashboard to track key performance indicators aligned with the core mechanisms: the density and quality of partnerships (social capital), the percentage of economic value retained locally (redistribution), and the speed of adaptive response to disruptions (resilience). This system transforms raw data into a strategic tool for continuous program adaptation and evidence-based policy learning.

Future research should advance along two interconnected directions. First, to empirically strengthen and quantify the proposed social mechanisms, we recommend a mixed-methods agenda combining: field surveys (validated scales for trust, co-operation, and pro-environmental behaviours); in-depth interviews and focus groups (governance processes and mechanism activation); social network analysis (mapping and quantifying stakeholder cooperation structures); quasi-experimental designs (leveraging phased lighting regulations or certifications); longitudinal tracking of SDG-aligned indicators; and participatory approaches (co-monitoring and citizen science). Second, although anchored in astrotourism, the proposed framework has strong transfer potential. Future studies should apply and stress-test it in other nature- and culture-based segments—ecotourism, geotourism, and cultural/heritage tourism—to examine how core mechanisms (trust, co-creation, value capture) interact with adjacent dimensions such as education, economics, technology, and culture. Pursued together, these pathways will validate the findings and extend their theoretical and practical relevance across the wider sustainable-tourism domain.

In conclusion, astrotourism emerges as a powerful living laboratory for social innovation and territorial regeneration. By mobilising social capital, redistributing power towards local actors, and coordinating collaborative responses to crises, it fosters resilience. Ultimately, when embedded within multi-scalar governance systems and measured through the lean, SDG-aligned indicators proposed, astrotourism effectively repositions peripheral territories, strengthens local identities, and opens credible pathways for inclusive and sustainable development in the twenty-first century.

_Li.png)