Abstract

Passion for studying represents a crucial motivational resource in students’ academic functioning, yet its role remains complex. Based on Vallerand’s dualistic model of passion, this paper examines how harmonious and obsessive study passion relate to students’ well-being, academic burnout, and dropout intentions. Across three complementary studies, we employed a multi-method approach combining cross-sectional correlational analyses (N = 142), longitudinal structural equation modeling (N = 100), and Bayesian psychological network analysis (N = 132). The results consistently indicated that harmonious passion was positively associated with well-being and negatively with burnout, psychological distress, and dropout intentions. Longitudinal findings confirmed its predictive role, showing that harmonious passion at the beginning of the semester protected against exhaustion and disengagement later on. In contrast, obsessive passion demonstrated weaker and less consistent associations, functioning mainly through links with anxiety in the network structure. Together, these findings suggest that harmonious passion acts as a central protective factor in students’ academic and emotional adjustment, whereas obsessive passion may represent a potential risk under certain conditions. By identifying the motivational and emotional mechanisms that sustain students’ well-being and engagement, this study contributes to the goals of sustainable education, emphasizing the creation of learning environments that support development of harmonious passion for studying, with its beneficial effects for long-term mental health.

1. Introduction

Research on study passion and its role in predicting academic functioning has gained increasing attention over the past decade (e.g., [1,2,3,4,5]). Passion represents a core motivational process for students, which can function both as a buffer against the risk of dropout and as a predictor of academic success. To capture the multidimensional nature of the relationship between these constructs, it is essential to apply diverse analytical approaches that highlight different facets of the phenomenon.

The dualistic model of passion (DMP) provides a robust framework for understanding students’ passion for studying as an intense and enduring desire for an academic activity that is personally significant, highly rewarding, and central to one’s life, with extensive time and energy devoted to it [6]. The DMP distinguishes between two types of passion, depending on how students internalize their motivation for engaging in academic activities [6].

A harmonious passion for studying emerges when students engage in their learning through personal approval and intrinsic motivation [6]. It is characterized by flexible and autonomous involvement that allows the activity to coexist harmoniously with other aspects of life. This form of passion has been associated with higher engagement, satisfaction, better interpersonal relationships, and greater well-being. It also serves as a buffer against negative outcomes in the academic context [2,4,5,7,8]. According to Verner-Filion and Vallerand [9], dropout intentions are negatively correlated with harmonious passion but not with obsessive passion. For instance, students with harmonious passion for studying can effectively manage schoolwork alongside other activities to attain deep engagement when studying and a balanced lifestyle.

Obsessive passion, in contrast, arises when engagement in studying is driven by external contingencies such as social pressure, the need for approval, or self-esteem regulation. This form of passion often leads to over-involvement and rigid commitment to schoolwork. Although it may result in short-term academic success, it is typically associated with maladaptive outcomes (e.g., [7,10]). For example, a student with obsessive study passion may neglect social activities, recreation or family life due to an uncontrollable urge to study and may feel guilty or distracted when not engaged in academic work. While passion involves intrinsic motivation, it extends beyond it by reflecting an internalization of the activity into one’s identity [11]. Unlike expectancy-value beliefs or self-regulation strategies, passion captures the enduring affective and identity-based engagement that sustains effort over time.

In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, higher education institutions are increasingly expected to foster not only academic achievement but also students’ psychological well-being and sustained engagement in learning. From this perspective, passion for studying can be viewed as a key personal resource contributing to sustainable education, one that strengthens resilience, protects against academic burnout, and promotes lifelong learning [11,12,13]. Understanding how harmonious and obsessive passion are linked to students’ functioning may thus offer valuable insights into how universities can create learning environments that sustain both performance and well-being, which are essential for sustainable societies.

While previous studies have typically examined the relationship between study passion and academic outcomes using either correlational or longitudinal designs [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], the present research integrates both longitudinal structural modeling and psychological network analysis within a single project. This multilevel methodological framework allows for a comprehensive examination of both the temporal stability and the structural complexity of passion-related mechanisms in student functioning. Each analytical approach highlights distinct facets of the interplay between passion and indicators of academic well-being, thus offering complementary perspectives on this multifaceted construct. By combining these approaches, the current project advances a more integrative understanding of study passion and enhances the robustness and validity of the inferences drawn [11,14,15].

Thus, the overarching aim of this paper was to examine how two types of study passion—harmonious and obsessive—relate to students’ well-being and academic functioning in a cohort of first-year university students. To achieve this, we conducted three complementary studies using different methodological approaches: (1) a cross-sectional correlational analysis, (2) a longitudinal structural equation model, and (3) a network analysis. Study 1 served as a preliminary validation phase, providing a baseline map of the relationships between passion, well-being, burnout, and mental health indicators. This information guided variable selection for the longitudinal (Study 2) and network (Study 3) analyses. Taken together, these studies allow us to explore not only the direction and stability of these relationships over time, but also their complexity within a system of interrelated psychological variables.

2. Study 1

Present Study

The study aimed to examine how different types of passion—harmonious and obsessive—relate to different indices of students’ academic functioning and mental health. Based on the results of previous studies, harmonious passion for studying is expected to be positively correlated with well-being and negatively correlated with two dimensions of academic burnout (i.e., exhaustion and disengagement), depression and anxiety symptoms, and dropout tendency; obsessive passion for studying is expected to be positively correlated with exhaustion, disengagement, dropout tendency, as well as depression and anxiety symptoms, and negatively with well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

The study sample consisted of 142 Polish-speaking students with an average age of 20.50 years (SD = 5.04, Median = 19.00, Min = 18, Max = 49). Females made up 82.39% of the group, males accounted for 11.97%, non-binary individuals represented 1.41%, and 4.23% chose not to specify their gender. Regarding place of residence, 47.18% lived in a large city (over 100,000 inhabitants), 26.76% in a rural area, 16.90% in a small town (up to 20,000 inhabitants), and 9.16% in a medium-sized city (20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants). Participants with higher education represented 8.45% of the sample, while the remaining ones had completed secondary education. In terms of relationship status, 69.01% were married or in an informal partnership, and 30.99% were single. The study was conducted using the paper-and-pencil method in October 2023. Participants were first-year university students recruited through organized data collection at the Kazimierz Wielki University (Poland). The study was conducted after scheduled classes with the consent of course instructors.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kazimierz Wielki University (opinions no. 2/12/01/2021 and no. 4/11/11/2024).

3.2. Measures

The Passion Scale [6,16], adapted for study passion, assesses harmonious passion and obsessive passion in the academic domain [17]. It consists of 12 items, six for harmonious passion (e.g., “Studying is in harmony with the other activities in my life”) and six for obsessive passion (e.g., “I am almost obsessed with studying”), respectively. Five items assessing the passion criteria allow distinguishing between students with and without study passion (e.g., “My studies are important to me”). A person is considered passionate if they meet the passion criteria, with an average score of at least 4. Responses are provided on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

The WHO-Five Well-being Index (WHO–5) is a 5-item self-report measure of positive well-being [18]. Items (e.g., “I feel cheerful and in good spirits”) are scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“at no time”) to 5 (“all the time”). Higher scores suggest greater well-being. In our study, we used the Polish adaptation of the WHO–5 scale [19].

The original Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) by Demerouti et al. [20] is designed to assess occupational burnout. In this study, we used a modified version adapted for academic settings, based on the Polish general version developed by Chirkowska–Smolak [21]. This student-specific adaptation has been previously used in study on academic burnout among Polish students [2]. The inventory consists of 16 statements (eight statements for measuring each dimension, e.g., exhaustion: “During my studies, I often feel emotionally drained”; disengagement: “It happens more and more often that I talk about my studies in a negative way”). Each subscale contains four positively worded and four negatively worded statements. The responses are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 4 (“strongly disagree”).

The PHQ-4 is a brief self-assessment tool consisting of four items, designed to evaluate symptoms of anxiety and depression experienced in the past two weeks [22]. The PHQ-4 has two subscales: anxiety (e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”) and depression (e.g., “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”), with two items in each subscale. The total PHQ-4 score represents an overall level of psychological distress. Each item on the PHQ-4 is rated using a 4-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of symptoms. We used the Polish version of the PHQ-4 [23].

Dropout intentions were assessed with a two-item scale of future dropout intentions (“I often consider dropping out of university” and “I intend to drop out of university”; [24]. The responses are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all my intention”) to 7 (“exactly my intention”).

3.3. Statistical Analyses

Pearson r correlation coefficient was used for correlation analysis to investigate the association between obsessive and harmonious passions for studying and different measures of academic functioning. Variables such as well-being, burnout, disengagement, dropout intentions as well as depression and anxiety symptoms were analyzed. The Lee and Preacher [25] calculator was used to investigate the difference between two dependent correlation coefficients that shared one common variable (i.e., harmonious, and obsessive passions for studying and well-being).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and internal consistency coefficients of the studied variables.

Table 1.

The means, standard deviations and reliability for studied variables (N = 142).

4.2. Analysis of Correlations and Comparative Correlation Coefficients

The results revealed that harmonious study passion was positively correlated with well-being and negatively correlated with exhaustion, disengagement, anxiety, depression, and drop-out intentions. Obsessive study passion showed negative correlation with dropout intentions, exhaustion, and disengagement. Exhaustion was negatively correlated with well-being but positively with disengagement, anxiety, and depression. Disengagement, as well as anxiety and depression, had high negative correlations with well-being, but the former had a positive and stronger correlation with drop-out intentions. Both drop-out intentions were highly correlated with each other (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson r correlations between the study variables (N = 142).

The results demonstrated that harmonious passion for studying was more strongly associated with positive academic outcomes (such as well-being) and more strongly negatively associated with negative outcomes (such as exhaustion, disengagement, anxiety and depression symptoms, and dropout intentions) compared to obsessive passion for studying (Table 3).

Table 3.

Difference in correlation coefficients between harmonious and obsessive passion for studying and indicators of academic functioning (N = 142).

5. Discussion

The present study contributes to the growing body of literature on the role of passion in students’ functioning and well-being. Consistent with earlier research [6,11], the findings highlight a positive association between harmonious passion and well-being and negative relationships with burnout, anxiety, and depression symptoms. The positive relationship between harmonious passion and well-being supports the idea that students who engage in activities driven by intrinsic interest and personal satisfaction experience more favorable psychological and affective outcomes [11]. The current findings extend these trends: students with higher harmonious passion reported greater well-being and lower exhaustion, disengagement, anxiety, and depression.

The results also revealed a robust and consistent negative relationship between dropout intentions and harmonious passion. When students achieve a balanced, intrinsically motivated approach to studying, they are significantly less likely to withdraw from their academic programs. This form of passion for study strengthens engagement, enhances stress coping behavior, and contributes to a more positive educational experience overall. These elements help protect students from burnout and academic withdrawal.

The sample of this Study 1 exhibited relatively low levels of obsessive passion. Given this tendency, participants may not have experienced the full psychological burden typically associated with high obsessive passion. This may explain the negative links with indicators such as exhaustion and disengagement, as well as dropout intentions, which were nonetheless weaker in magnitude compared to those observed for harmonious passion. These results suggest that obsessive passion, at moderate levels, may still provide some adaptive effects, although its protective value appears limited when contrasted with the potential buffering effects of harmonious passion.

Moreover, we demonstrated that dropout intentions were highly correlated with symptoms of exhaustion, disengagement, depression, and anxiety. These findings align with Tinto’s [26] model of psychological withdrawal, which posits that emotional strain and stress increase students’ vulnerability to leaving university.

Limitation concerns the internal consistency of the disengagement subscale, which was moderate in this sample (α = 0.56, ω = 0.60). This lower reliability is not uncommon for multidimensional constructs that encompass both cognitive and emotional components and include reverse-keyed items [20]. Nevertheless, it may have attenuated some of the observed associations, suggesting that the reported effects should not be interpreted as definitive estimates.

These findings suggest initial support for the adaptive function of harmonious passion and the potentially maladaptive effects of obsessive passion. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits causal interpretation. Therefore, in Study 2, we examine these relationships using a longitudinal design to assess temporal stability and predictive effects.

6. Study 2

Present Study

The main goal of this study was to develop a model in which each variable assessed at Time 1 (T1) was also assessed at Time 2 (T2). This design allowed us to account for the consistency of variables over time, examine the direction of effects, and identify any potential cross-lagged relationships. Using this longitudinal approach, we aimed to explore how both harmonious and obsessive passion for studying influenced later experiences of academic burnout and well-being.

The study was guided by the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

When controlling for the stability of all variables, harmonious passion for studying at T1 will be a negative predictor of academic burnout (specifically exhaustion and disengagement) at T2, and a positive predictor of well-being at T2.

Hypothesis 2.

When controlling for the stability of all variables, obsessive passion for studying at T1 will be a positive predictor of academic burnout (exhaustion and disengagement) at T2, and a negative predictor of well-being at T2.

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Participants and Procedure

The sample in this study included 100 first-year students from the Kazimierz Wielki University with an average age of 19.09 years (SD = 1.44, Median = 19.00, range: 18–29 years). The group comprised 83.00% women, 10.00% men, 2.00% non-binary individuals, and 5.00% people who did not disclose their gender. In terms of residence, 40.00% lived in large cities (over 100,000 inhabitants), 32.00% in rural areas, 18.00% in small towns (up to 20,000 inhabitants), and 10.00% in medium-sized cities (20,000–100,000 inhabitants). Only 1.00% of participants had received higher education, while the rest had completed secondary education. Regarding relationship status, 74.00% were either married or in an informal relationship, whereas 26.00% were single.

The first stage of the study was conducted in October 2023, and the second in February 2024. Both were carried out using the paper-and-pencil method. Each student was assigned a code that allowed their results from both measurements to be combined.

7.2. Measures

The Passion Scale for studying, The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) and the WHO–Five Well–being Index (WHO–5) were described in Study 1.

7.3. Statistical Analyses

To evaluate our hypotheses, we applied structural equation modeling (SEM) using JASP. This method is well-suited for examining complex relationships between latent and observed variables [15]. SEM enables the simultaneous testing of multiple dependent variables while considering both autoregressive effects and cross-lagged associations across time [27]. Given that our data were collected at two time points (T1 and T2), this approach was particularly appropriate for analyzing how harmonious and obsessive passion for studying at T1 influenced academic burnout and well-being at T2.

To test Hypothesis 1, we built a model in which harmonious passion for studying at T1 was expected to negatively predict academic burnout at T2, specifically in terms of exhaustion and disengagement or cynicism. In addition, we expected to find a positive association between harmonious passion and well-being at T2. Each model included autoregressive paths in order to control for the temporal stability of the variables, as recommended in longitudinal SEM research [27].

For Hypothesis 2, we tested whether obsessive passion for studying at T1 positively predicted academic burnout at T2 and negatively predicted well-being at T2. As with the first model, we included autoregressive paths to account for stability over time. This autoregressive cross-lagged framework allowed us to differentiate between short-term and long-term effects of passion on psychological outcomes, in line with prior research on passion and well-being [6,28].

The models were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method, which is commonly used in SEM due to its reliability in assessing relationships among multiple variables [29]. We evaluated model fit using several widely recommended indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) [30]. According to established guidelines, a model was considered to have acceptable fit if CFI and TLI values exceeded 0.90, and RMSEA and SRMR values were below 0.08 [15].

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations of the studied variables. Internal consistency coefficients were included.

Table 4.

The means, standard deviations, and reliability for studied variables (N = 100).

In cross-sectional analyses (Study 1), harmonious passion for studying was positively correlated with obsessive passion for studying and well-being, and negatively correlated with exhaustion and disengagement. Well-being was negatively correlated with burnout and disengagement. Exhaustion was positively related to disengagement. The obtained results were reflected in the longitudinal study, which assessed the relationships between the variables from the first measurement and the variables from the second measurement (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson r correlations between the study variables (N = 100).

8.2. Structural Equation Modeling

The model included ten variables: five in the first time point (Time 1) and five in the second one (Time 2). Harmonious passion, obsessive passion, well-being, exhaustion, and disengagement were included. The presented model had an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (df = 18, n = 100) = 27.185, p = 0.076, AIC = 5264.470, RMSEA = 0.071 (0.000; 0.123), SRMR = 0.063, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.963. Given the lack of associations involving obsessive passion, the model excluding it was tested. A model with poorer fit indices was obtained (χ2 (df = 11, n = 100) = 32.986, p < 0.001, AIC = 3455.789, RMSEA = 0.141 (0.087–0.198), SRMR = 0.069, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.896), therefore this model was not further used.

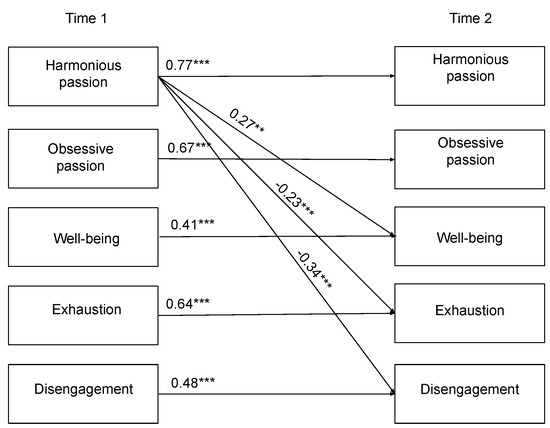

A strong relationship was observed between the results of harmonious passion in the first and second measurements. Harmonious passion at Time 1 positively affected well-being at Time 2 and negatively affected exhaustion and disengagement at Time 2.

Obsessive passion showed a relatively strong autocorrelation, which also suggests its stability. It was a variable with slightly less stability than harmonious passion. The model did not indicate direct effects of obsessive passion at Time 1 on burnout or well-being within the same measure. This suggests that obsessive passion functions in a more insulating way, and its influence on other variables is limited to autocorrelation.

The obtained results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results of the model in Study 2: A longitudinal design. Note. Standardized (latent-variable) path coefficients are shown. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Covariance values among constructs are reported in Table A1.

9. Discussion

Harmonious passion is typically considered a stable and enduring trait. Individuals who begin with high levels of harmonious passion tend to maintain their engagement over time. Previous studies have consistently shown that this type of passion is linked to greater well-being, lower stress levels, and reduced risk of burnout [2,31]. It serves as a psychological resource that helps individuals cope with challenges more effectively [32,33].

In this study, harmonious passion measured at Time 1 was positively associated with well-being and negatively associated with exhaustion and disengagement at Time 2. These results suggest that harmonious passion may serve as a protective function against long-term exhaustion and disengagement. People who are harmoniously engaged are more likely to remain committed to their activities over time, which can help sustain motivation and reduce the likelihood of burnout. These findings may reflect the self-determined nature of harmonious passion, which enables individuals to experience autonomy, meaning, and deep engagement [34]. This form of passion is less likely to generate internal conflict or cognitive dissonance, thereby reducing strain and emotional fatigue over time.

In contrast, obsessive passion did not show direct associations with any outcomes in the SEM model. The absence of direct effects may suggest that its role is more conditional or indirect. Additionally, obsessive passion may fluctuate depending on situational stressors or external expectations, making its long-term predictive power less stable.

When integrated with previous research, the current SEM results provide a consistent picture of the relationship between harmonious and obsessive passion and well-being and academic burnout. Fostering harmonious passion while regulating obsessive passion through psychological or organizational interventions appears well supported by literature and may positively influence both well-being and academic functioning.

One important consideration is the sample size. In structural equation modeling (SEM), the minimum ratio of often-cited guidelines is 10 observations per variable [35]. That standard was achieved in the present study to support the reliability and appropriate model estimation. Further, the SEM model was theory-driven and grounded in prior empirical evidence, which supports the validity of the tested relationships even when using moderate samples sizes. Although larger samples are preferable for SEM, previous research demonstrated that models based on strong theoretical foundations can yield stable and interpretable estimates even with samples of around 100 participants [35,36].

The longitudinal model confirmed the beneficial role of harmonious passion over time, yet associations involving obsessive passion were non-significant. To explore the structural interrelations among the study variables further, we conducted the Study 3, using network analysis.

10. Study 3

Present Study

Although this area of research continues to grow, relationships between passion, well-being, depression, and anxiety remain difficult to clarify using traditional linear methods. Correlation or regression methods are frequently insufficient to capture the complexity of psychological constructs, due to typical linearity assumptions that one construct always has a unidirectional and homogeneous effect upon a subsequent one. Network analysis is, therefore, an increasingly preferred method, offering a less rigid and dynamic way to examine psychological systems. Here, psychological constructs are treated as nodes within a network, linked via differing relationships (edges), thereby able to examine how varied components interact visually and spatially [37]. Rather than separately isolating passion, well-being, depression, and anxiety, network analysis views them as part of an interacting structure whereby one construct may indirectly contribute to another one via shared interconnections.

Applying network analytical techniques to studying academic passion, well-being, depression, and anxiety has both theoretical and practical advantages. Theoretically, this can be employed to highlight the most central nodes within the network—the ones exerting central influence upon other nodes. Network analysis may, for example, indicate how reductions in well-being or increases in anxiety symptoms are a consequence of obsessive passion, while harmonious passion is implicated in a buffering/protective role. Practically, this can grant access to targeted intervention. If one can identify those variables with central positions within the network, then interventions can be created to directly act upon those central constructs, thus improving emotional well-being while reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety [38].

To investigate the relationships between passion (both harmonious and obsessive), well-being, and symptoms of anxiety and depression, we carried out network analysis. This method makes it possible to examine the complex interactions among multiple psychological constructs and provides insights into how these variables are connected within a broader system.

11. Materials and Methods

11.1. Participants and Procedure

The study initially enrolled 136 first-year students. The analysis ultimately included 132 individuals meeting the criteria for passion (≥4) with an average age of 19.21 (SD = 1.25, Median = 19.00, Min = 18, Max = 29). Females constituted 81.82% of the sample, males—11.36%, non–binary individuals—2.27%, and 4.55% did not indicate their gender. As for residency, 45.46% lived in a large city (above 100,000 inhabitants), 28.79%—a village, 14.39%—a small town (up to 20,000 inhabitants), and 11.36%—a medium city (from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants). Individuals with higher education constituted 1.152%, and the rest had secondary education. Exactly 69.70% were married or in an informal relationship, 29.55% were single, and one person did not indicate their status.

The study was conducted using the paper-and-pencil method in June 2024. Students were recruited among first-year university students using the snowball method.

11.2. Measures

The Passion Scale for studying, The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) and the WHO–Five Well–being Index (WHO–5) were described in Study 1.

11.3. Statistical Analyses

As a first step, we calculated descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and examined correlations to explore the basic relationships among variables. This preliminary analysis provided a general overview of how the variables were related and served as a foundation for the subsequent network modeling.

We then conducted a Bayesian network analysis using a GGM estimator. A Bayesian network consists of a directed acyclic graph in which each node is linked to conditional probability distributions. This structure makes it possible to explore potential causal relationships between variables. In such graphs, nodes located upstream are often interpreted as key drivers or core symptoms that may be useful intervention targets [39]. In the resulting visualizations, the thickness and saturation of each edge reflect its weight, with thicker and more saturated edges indicating stronger relationships between nodes [40]. We also applied a color-coding scheme in which red edges represent negative associations and blue edges indicate positive associations [40].

There is an ongoing debate about how to interpret node centrality indices in psychological networks. For this reason, we did not report all centrality metrics—specifically betweenness and closeness—since previous studies have raised concerns about their reliability and interpretability in psychological contexts [41]. Instead, we focused on two centrality indices: strength and expected influence. These were selected based on recommendations by Epskamp et al. [42,43] to ensure interpretability and relevance. Strength centrality reflects the overall degree of connectedness of each node and helps to identify which constructs are most integrated within the network. This aligns with the perspective offered by Fried et al. [44] who suggested that highly connected symptoms may be optimal targets for intervention.

To better capture the influence of both positive and negative associations, we also examined expected influence. This metric, introduced by Robinaugh et al. [45], considers the direction (valence) of relationships, distinguishing between positive and negative edges, when estimating to which extent a node impacts the rest of the network. This provides a more nuanced understanding of role of each variable within the broader system.

12. Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 6 shows the means and standard deviations for the variables under investigation, along with the internal consistency coefficients.

Table 6.

The means, standard deviations, and reliability for studied variables (N = 132).

Harmonious passion was moderately positively associated with well-being and weakly negatively associated with anxiety and depression symptoms. Well-being was strongly negatively related to anxiety and depression symptoms. A quite a high correlation between anxiety and depression symptoms was noted (Table 7).

Table 7.

Pearson r correlations between the study variables.

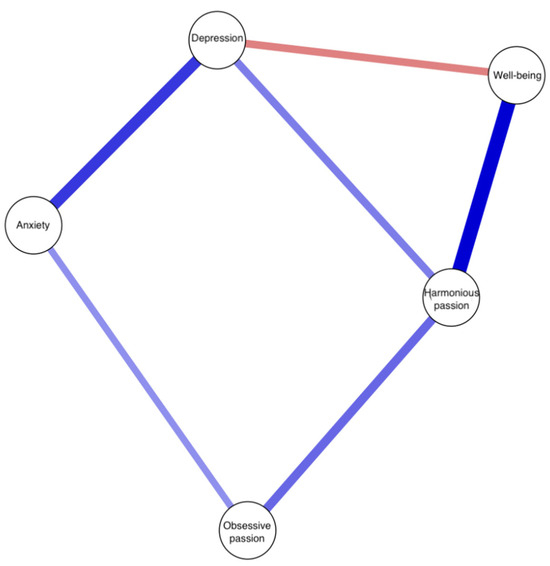

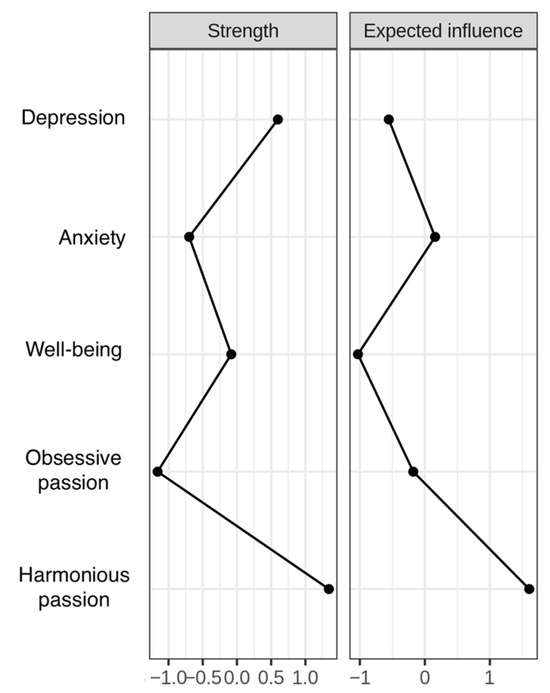

The network analysis is illustrated in Figure 2. The centrality plots for each node are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Network plots for harmonious and obsessive passion in relation to mental health. Note. Edge color denotes the sign of the association (blue = positive, red = negative). Edge width encodes the magnitude of the effect, and opacity reflects confidence/significance (more opaque = stronger/more significant).

Figure 3.

The centrality plots for each node (z-scores).

In the network analysis, harmonious passion demonstrated a relatively high normalized strength score (1.338), indicating that it played a more central role within the network compared to other nodes. The positive expected influence (1.603) shows that harmonious passion was connected through predominantly positive associations, including links with well-being and, to a lesser extent, depressive symptoms.

Obsessive passion, in contrast, exhibited a negative normalized strength score (−1.143), which implies that it is less centrally integrated within the network. However, it remains connected to key constructs, such as anxiety and harmonious passion. The slightly negative expected influence (−0.168) indicates that, while not strongly central, obsessive passion is linked with less adaptive emotional processes, particularly through its positive association with anxiety.

Well-being had a near-zero normalized strength score (−0.095), suggesting minimal direct influence on other nodes in the network. Its strongly negative expected influence (−1.035) reflects that it was primarily connected through negative links with distress-related variables such as depression.

Anxiety showed negative strength (−0.717), suggesting lower-than-average centrality. It acted as a bridge node connecting obsessive passion and depression, with a slightly positive expected influence (0.153).

Finally, depression displayed moderately high normalized strength (0.617), indicating a relatively central role in the network. Its negative expected influence (−0.553) shows that it was predominantly connected through negative relations, particularly with well-being.

In summary, harmonious passion was the most central and positively connected variable, obsessive passion and anxiety formed a bridge between motivational and affective constructs, and depression and well-being were inversely linked within a shared distress cluster.

13. Discussion

Bayesian network outcomes yield insight into how obsessive and harmonious passions for studying relate to mental health variables like well-being, depression, and anxiety. Overall, results feature distinctive psychological operations that each type of passion holds within the overall network with practical as well as theoretical implications.

The findings suggest that there are high strength centrality and a positive expected influence for harmonious passion, hence it is a central and positive feature within the network. This aligns with prior work reporting beneficial psychological correlates of harmonious passion [6,31]. The positive relation with well-being supports the notion that harmonious passion is linked with adaptive functioning and emotional balance, although its broader network connections suggest that this relationship may depend on contextual factors such as co-occurring obsessive tendencies. The high value for strength further implies that there are strong relations between harmonious passion and other variables within the system, therefore its influence can propagate throughout the entire network.

While obsessive passion possesses negative strength and rather low expected influence, indicative of its maladaptive position within the network, its positive associations with anxiety are compatible with previous work implicating obsessive passion as an antecedent to psychological ill-being [7,46,47]. Unlike harmonious passion, obsessive passion involves a more compulsive and entrenched pattern of engagement, as individuals feel bound to continue with an activity despite its negative effect on well-being. The compulsive nature of this pattern may be responsible for its association with negative sequelae, as people are pushed toward activities amplifying their stress and discomfort.

Notably, there exists a significant association between depression and harmonious passion in the network. One possible explanation is that there can be indirect consequences of the association between obsessive passion and anxiety for the relations between depression and harmonious passion. Given this pattern, obsessive passion being linked with anxiety can have spillover consequences leading to stress and obsessive passion spilling over into a broader psychological context. Such a process can repress the otherwise buffering effect of harmonious passion as obsessive traits will tend to generalize a negative affect [32].

Well-being, depression, and anxiety had distinctive centrality indices, which were characteristic of their respective locations within the network. Well-being showed weak strength and a strongly negative expected influence, indicating that it was minimally connected and primarily influenced by other constructs, particularly depression and harmonious passion. This pattern supports the notion that well-being functions primarily as a reactive outcome, rather than a driving force within the psychological network [48].

Anxiety and depression, however, had low to moderate strength and a negative expected influence value (depression), indicative of rather central and distress-related nodes of the network. The position suggests that interventions aimed at such constructs will have wide-ranging advantages, thus targeting these nodes in interventions may help weaken maladaptive associations and promote more adaptive network dynamics. The interpretation is consistent with previous research that indicated that anxiety and depression are central symptoms within psychological distress models [44], and it highlights their clinical significance.

Additionally, the positive connection between harmonious and obsessive passions observed in the network is consistent with previous research showing that both forms of passion can coexist within individuals [6,47]. This pattern suggests that strong engagement in studying may involve both flexible and rigid forms of internalization, depending on contextual pressures and personal standards.

Overall, results indicate a complex but meaningful interplay between harmonious and obsessive passions, and important mental health outcomes. Both types of passion appear to influence well-being, depression, and anxiety in different ways.

14. General Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on academic passion by integrating three complementary methodologies: cross-sectional correlation, longitudinal structural equation modeling (SEM), and psychological network analysis. This multilevel approach allowed us to examine not only general associations between passion and well-being but also their temporal and structural dynamics within students’ psychological systems. While earlier research has shown the adaptive value of harmonious passion and the risks of obsessive passion (e.g., [11,47]), our combination of longitudinal and network perspectives provides a more comprehensive picture of how these two forms of passion function over time and within interrelated emotional processes.

Across all analyses, harmonious passion consistently emerged as a beneficial factor. It was positively associated with well-being and negatively related to burnout, anxiety, and depression, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Similarly, in the network model, harmonious passion also occupied a central and integrative position suggesting that it may serve as a stabilizing psychological resource that maintains balance and coherence in students’ emotional systems.

However, the findings for obsessive passion were more complex and context-dependent. Although its direct correlations with well-being and mental-health indicators were weak or nonsignificant, network analysis revealed that obsessive passion was indirectly connected to anxiety, implying that it may contribute to emotional strain within the broader affective system. The coexistence of harmonious and obsessive passion, also observed in earlier research [7,47], suggests that even adaptive engagement may take a maladaptive turn when combined with internal pressure or perfectionistic striving.

Finally, integrating results across Studies 2 and 3 underscores that the two methodological approaches yield complementary insights: the longitudinal model captures predictive trajectories over time, whereas the network approach illuminates concurrent structural dependencies among constructs. Together, these findings support viewing academic passion as a dynamic and context-sensitive process rather than a static trait, highlighting the importance of employing multimethod designs to understand students’ well-being and adjustment in higher education.

Limitations, Practical Implications and Future Research

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample size was relatively small and predominantly female, which may limit the generalizability of the results to more diverse student populations. Future studies should aim to replicate these findings in larger, gender-balanced samples and across different educational and cultural contexts.

The present results have significant implications for student support programs and psychological interventions in higher education. Supporting healthy academic involvement, grounded in intrinsic motivation, and characterized by flexible and balanced engagement, may foster students’ well-being, and protect them from emotional exhaustion. The observed association between obsessive passion and anxiety symptoms highlights the need for psychoeducational interventions that help students recognize early signs of maladaptive overcommitment. Institutions can also benefit from implementing screening instruments that distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive forms of involvement, enabling them to provide more tailored support.

Future research should evaluate intervention strategies that promote harmonious engagement while reducing obsessive patterns of involvement, ideally through longitudinal or experimental designs. It will also be important to examine potential moderating conditions, such as perfectionism, fear of failure, or institution-related pressure, that may amplify the negative effects of obsessive passion [11,47]. Furthermore, applying network models to coping strategies or emotion regulation styles could provide deeper insights into the psychological mechanisms through which academic passion influences mental health outcomes.

Finally, the findings underscore the role of harmonious passion as a protective factor for students’ academic and psychological adjustment. This resonates with the broader agenda of sustainable education, which emphasizes creating learning environments that nurture not only academic achievement but also mental health and lifelong learning. By fostering harmonious rather than obsessive passion, universities may contribute to the cultivation of sustainable learners—individuals capable of maintaining motivation, balance, and well-being throughout their studies and beyond. Such outcomes directly align with SDG and indirectly support the development of resilient and adaptive societies.

15. Conclusions

Together, the three studies presented in this paper provide converging evidence for the distinct roles of harmonious and obsessive study passions in academic functioning. The use of diverse methodologies strengthens the validity of the findings and highlights the importance of approaching passion as a dynamic, multidimensional construct with both adaptive and maladaptive pathways.

This investigation provides important insights into the central significance of healthy passion for studying as one of the strongest antecedents of students’ well-being, long-term motivation, and reduced risk of burnout and dropout. In contrast, obsessive passion was found to predict maladaptive outcomes, which is consistent with previous research showing that such effects are particularly pronounced among highly achievement-oriented or perfectionistic students whose self-worth is strongly tied to performance [7,11,47].

In sum, a harmonious passion for studying plays a pivotal role in sustainable education by promoting student well-being, reducing dropout intentions, and supporting lifelong engagement in learning. These insights contribute to ongoing efforts to achieve sustainable development and to design higher education systems that prepare students not only for academic success but also for sustainable personal and societal development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.-G. and P.L.; methodology, K.M.-G. and P.L.; formal analysis, K.M.-G.; investigation, K.M.-G. and P.L.; data curation, K.M.-G. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.-G. and P.L.; writing—review and editing, K.M.-G. and P.L.; visualization, K.M.-G.; project administration, K.M.-G.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Kazimierz Wielki University Ethics Committee (opinions no. 2/12/01/2021 and no. 4/11/11/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study for their effort.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Residual covariances among latent constructs in the longitudinal SEM model.

Table A1.

Residual covariances among latent constructs in the longitudinal SEM model.

| Variables | Estimate | SE | z | p | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | Standardized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1HP–1OP | 9.68 | 2.93 | 3.30 | <0.001 | 3.94–15.42 | 0.35 |

| 1OLBIexh–1OLBIdis | 2.35 | 0.87 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 0.65–4.05 | 0.28 |

| 2OLBIdis–2OLBIexh | 1.74 | 0.51 | 3.43 | <0.001 | 0.75–2.74 | 0.37 |

| 2HP–2OP | 1.20 | 1.49 | 0.81 | 0.420 | −1.72–4.13 | 0.08 |

| 2HP–2OLBIdis | −1.62 | 0.65 | −2.48 | 0.013 | −2.90–−0.34 | −0.26 |

| 2HP–2OLBIexh | −2.82 | 0.94 | −3.02 | 0.003 | −4.65–−0.99 | −0.32 |

| 2HP–2WHO | 4.41 | 1.25 | 3.51 | <0.001 | 1.95–6.87 | 0.38 |

| 2OP–2OLBIdis | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.851 | −1.42–1.72 | 0.02 |

| 2OP–2OLBIexh | 0.54 | 1.13 | 0.48 | 0.63 | −1.66–2.75 | 0.05 |

| 2OP–2WHO | −0.48 | 1.48 | −0.33 | 0.75 | −3.39–2.42 | −0.03 |

| 2OLBIdis–2WHO | −1.81 | 0.66 | −2.76 | 0.01 | −3.09–−0.52 | −0.29 |

| 2OLBIexh–2WHO | −4.73 | 1.01 | −4.71 | <0.001 | −6.70–−2.76 | −0.53 |

Note. HP = Harmonious Passion; OP = Obsessive Passion; WHO = Well-being; OLBIexh = Exhaustion; OLBIdis = Disengagement. The prefixes “1” and “2” denote the measurement occasions: T1 and T2, respectively. Covariances are estimated among residual latent constructs within each time point (T1 or T2). Standardized coefficients (β) are reported in the final column.

References

- Larionow, P.; Gabryś, A. Psychological characteristics of students with passion for studying. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Larionow, P. The role of study passion in the subjective vitality, academic burnout and stress: The person-oriented approach and latent profile analysis of study passion groups. Colloquium 2023, 15, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Larionow, P. Passion for studying and emotions. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, B.K.; Bureau, A.; Eckenrode, C.; Maley, M. Passion and burnout in college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2018, 52, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zinczuk-Zielazna, J. Pasja Studiowania a Samoregulacja, Emocje i Jakość Relacji Akademickich; Wydawnictwo Rys: Dąbrówka, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Childs, J.H.; Hayward, J.A.; Feast, A.R. Passion and motivation for studying: Predicting academic engagement and burnout in university students. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. How does dualistic passion fuel academic thriving? A joint moderated-mediating model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 666830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verner-Filion, J.; Vallerand, R.J. On the differential relationships involving perfectionism and academic adjustment: The mediating role of passion and affect. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 50, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, C.; Tricio, J.; Tapia, D.; Segura, C. How dental students’ course experiences and satisfaction of their basic psychological needs influence passion for studying in Chile. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. The Psychology of Passion: A Dualistic Model; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. A commentary on education and sustainable development goals. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lafrenière, M.A.K.; Parker, P.; Morin, A.J.; Carbonneau, N.; Paquet, Y. Passion: Does one scale fit all? Construct validity of two-factor passion scale and psychometric invariance over different activities and languages. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Lewandowska, M.; Kasprzak, E. Adaptation and validation of a tool for measuring harmonious passion and obsessive passion: The Passion Scale by Marsh and colleagues. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 62, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P. Anxiety and depression screening among Polish adults in 2023: Depression levels are higher than in cancer patients. Psychiatria 2023, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Vardakou, I.; Kantas, A. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkowska-Smolak, T. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do pomiaru wypalenia zawodowego OLBI (The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory). Stud. Oecon. Posnan. 2018, 6, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ–4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4: Factor structure, measurement invariance, latent profile analysis of anxiety and depressive symptoms and screening results in Polish adults. Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 2023, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Fortier, M.S.; Guay, F. Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.A.; Preacher, K.J. Calculation for the Test of the Difference Between Two Dependent Correlations with One Variable in Common, Computer Software. Available online: https://quantpsy.org/corrtest/corrtest2.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Selig, J.P.; Little, T.D. Autoregressive and cross–lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In Handbook of Developmental Research Methods; Laursen, B., Little, T.D., Card, N.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z.; Nagengast, B.; Morin, A.J.S.; Trautwein, U. Latent variable models of longitudinal data. In The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences; Kaplan, D., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F.L.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lavigne, G.L. Passion does make a difference in people’s lives: A look at well-being in passionate and non-passionate individuals. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2009, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, E.; Mudło-Głagolska, K. Teachers’ well-being forced to work from home due to COVID-19 pandemic: Work passion as a mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Larionow, P. The role of harmonious and obsessive work passion and mental health in professionally active people during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland: The mediating role of cognitive coping strategies. Colloquium 2021, 13, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Cramer, A.O.J. Moving forward: Challenges and directions for psychopathological network theory and methodology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M.C.; Marchetti, I.; Beevers, C.G. Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, L.F.; Elmer, T.; Epskamp, S.; Krause, R.W.; Schoch, D.; Wichers, M.; Wigman, J.T.W.; Snippe, E. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S.; Waldorp, L.J.; Mõttus, R.; Borsboom, D. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, E.I.; Epskamp, S.; Nesse, R.M.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Borsboom, D. What are ‘good’ depression symptoms? Comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression in a network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Appleton, P.R.; Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K. Passion and burnout in elite junior soccer players: The mediating role of self-determined motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Hill, A.P.; Appleton, P.R.; Vallerand, R.J.; Standage, M. The psychology of passion: A meta-analytical review of a decade of research on intrapersonal outcomes. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).