Abstract

Empirical research has revealed conflicting associations between dependent and independent variables, with few studies tackling the dynamics in developing economies. This study investigates the effects of carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption (REC), foreign direct investment (FDI), government green capital spending (GGCS), and economic growth (EG) in Morocco, employing the Keynesian framework of economic growth. An autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) methodology was applied to assess both short- and long-term relationships among the model’s variables, using annual data from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database for the period 1993–2020. All ARDL variables were transformed into first differences to ensure stationarity. The bounds test confirmed a long-term equilibrium relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Diagnostic tests, including the White test, indicated no evidence of heteroscedasticity, and the Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed that residuals followed a normal distribution, validating model robustness. The model demonstrated overall stability across the study period with no structural breaks. The empirical findings suggest that both carbon dioxide emissions and renewable energy consumption exhibit positive trends, whereas GGCS demonstrates a significant short-run negative correlation with economic growth. However, the long-term coefficients were found to be statistically insignificant, suggesting that sustained policy effects may be attenuated by macroeconomic structural factors.

1. Introduction

Economic growth is a vital concept in economics, measured by the sustained increase in a nation’s production of goods and services over time. Other key indicators of economic progress include employment levels, human development, and per capita income [1]. For decades, scholars and policymakers have been interested in the relationship between economic expansion and human capital [1]. Yet empirical evidence in the past literature has revealed inconsistencies, mainly regarding how government spending, renewable energy adoption, and carbon dioxide emissions interact to shape the sustainability of economic growth [1].

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been viewed as a catalyst for development, offering various advantages. Such advantages include technology transfer, managerial skill enhancement, market access, and potential employment generation [2,3]. However, domestic investment remains vital for the establishment of a solid infrastructural foundation, which is considered important for sustained growth and innovation [4].

Morocco has successfully attracted substantial FDI projects in sectors such as chemicals, electric vehicles, renewable energy, and tourism. Moreover, government incentives and policy frameworks have played a crucial role in supporting investment in these key industries and promoting economic diversification [5]. Furthermore, strategic policy frameworks such as the Investment Charter have enhanced Morocco’s competitiveness and capacity to attract foreign investment in major sectors such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, and semiconductors, resulting in an observed increase in FDI inflows [3].

Economic theories such as the Keynesian demand theory highlights the role of government spending in enhancing public goods provision and improving economic well-being [6]. Like many other developing nations, Morocco faces mounting pressures and challenges related to climate change, which has prompted short- and medium-term renewable energy development initiatives. Paradoxically, limited empirical research has explored how Morocco’s economic development, per capita carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption, FDI inflows, and public expenditure contribute to GDP.

The current research intends to contribute to the literature by addressing the above gap by investigating the relationships between economic growth, per capita carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption, FDI, and government final consumption expenditure in Morocco from 1993 to 2020. Additionally, this study aims to provide fruitful insights regarding such interconnections, particularly within Morocco’s cultural and economic context. The proposed constructs are based on past empirical studies conducted within the Moroccan framework [1,7,8]. Therefore, from a practical perspective, the findings of this study are of extreme importance when it comes to designing holistic strategies that promote sustainable growth while maintaining environmental stewardship. Lastly, this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant theoretical and empirical literature. Section 3 outlines the methodology, proposed conceptual model, and data sources. Section 4 presents the interpretations of the findings. Section 5 concludes with key findings, strategic implications, and policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

A fundamental pillar of economic literature is concerned with the bond between energy consumption and economic growth. The pioneering work by Kraft and Kraft (1978) founded a persistent debate on the notion of causality between these two constructs [9,10]. Within the context of renewable energy, empirical research has often yielded conflicting and mixed results [9,10]. Chen et al. (2020) supported the findings of Taher (2017) in Lebanon, showing a significant positive correlation between economic growth and renewable energy utilization [11,12]. The aforementioned body of research recognized an important threshold, suggesting that the positive impact that renewable energy has on growth only becomes significant once a certain consumption scale is realized. Such findings highlight that renewable energy’s contribution to growth is conditional rather than automatic, depending on the requisite structural and technological conditions.

An equally essential literature stream examines environmental degradation, frequently measured by carbon dioxide emissions and its linkage to economic growth according to the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) framework. Evidence from Malaysia has revealed a positive relationship between GDP and carbon dioxide emissions during the early stages of development, hence supporting the traditional EKC model [13,14]. Nevertheless, as sectoral analyses demonstrate, this relationship is dynamic and can be influenced by environmental policies, energy composition shifts, and technological innovations.

Also, foreign direct investment (FDI) plays a pivotal role within this analytical framework. In Latin America, salient benefits to FDI have been realized in relation to technology spillovers and enhanced competitiveness. Still, these positive effects remain liable to domestic absorptive capacities, such as the availability of skilled labor and institutional quality and stability. Conversely, the “pollution haven” hypothesis that FDI may flow in pollution-intensive sectors, creating a dilemma for policymakers between environmental protection and economic development advancement [15,16].

Another persistent debate within public economics concerns the impact of government expenditure on economic growth. According to Keynesian theory public spending stimulates aggregate demand and generates economic expansion through a multiplier effect. Even so, empirical investigation yields inconsistent results [6]. For example found that research and development (R&D) spending positively affects economic growth, whereas stressed the potential negative downsides of inefficiencies and resource misallocation [17,18]. In other words, they argued that the growth impact of government spending depends significantly on the composition, nature, and quality of expenditures, specifically, productive investment versus current consumption [17,18].

From a contextual viewpoint, Morocco’s economic development strategy, which integrates bold renewable energy initiatives with the employment of aggressive strategies to induce foreign direct investment, merits special attention. Previous studies, have proven connections between economic growth, energy consumption, and environmental performance at the national level [1,8]. This body of literature ensures a predominantly positive relationship between renewable energy utilization and economic growth while acknowledging hindering gaps. For example, there is an absence of a holistic integrated joint analysis that evaluates the aggregate effect of carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy, FDI, and public expenditure on Morocco’s development trajectory. As a result, the present research intends to address this shortcoming. By advancing empirical analysis that is not constrained by theoretical preconceptions, the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) methodological approach offers an ideal framework for reconciling such inconsistencies. Additionally, the ARDL approach’s ability to differentiate between short- and long-term dynamics within mixed-integration data proves valuable for assessing theoretically ambiguous relationships, such as the observed positive association between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth. Consequently, the hypotheses formulated in this study constitute empirical propositions for rigorous testing rather than rigid claims derived from a single theoretical paradigm. To conclude, the identification of long-term positive relationships through bounds cointegration testing, coupled with subsequent adjustment dynamics analysis, provides robust empirical validation. This confirms the presence of a stable, long-run equilibrium among the variables, suggesting that, despite limited theoretical consensus, the model effectively captures a persistent and meaningful economic reality within the Moroccan setting [17,18].

2.1. Research Gap

Despite having a considerable body of literature that has tackled the bilateral relationships among diverse variables from multi-dimensional perspectives (economic, environmental, and energy) in Morocco, few studies have conducted a comprehensive integrative analysis of the combined effects of carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy utilization, foreign direct investment (FDI), and government final consumption expenditure on the country’s economic growth from a holistic point of view, leaving the literature notably scarce. Thus, this study intends to bridge the gap in the literature in three main areas.

Firstly, limited attention has been given to the establishment of a coherent link between Keynesian macroeconomic theory and energy production dynamics, mainly in models that explicitly incorporate energy-related determinants. Secondly, the scholarly literature shows insufficient integration of the research variables within a cohesive framework that is adjusted to Morocco’s distinctive nature. Thirdly, little empirical work has simultaneously examined short- and long-run adjustment mechanisms using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) methodology to clarify the paradoxical relationships characterizing the Moroccan economy, such as the seemingly positive power of carbon dioxide emissions on growth. To summarize, this investigation contributes by explaining these substantive deficiencies by proposing an integrated empirical framework that thoroughly captures the multifaceted interdependencies between environmental, energy, and macroeconomic variables within Morocco’s sustainable development context. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be hypothesized:

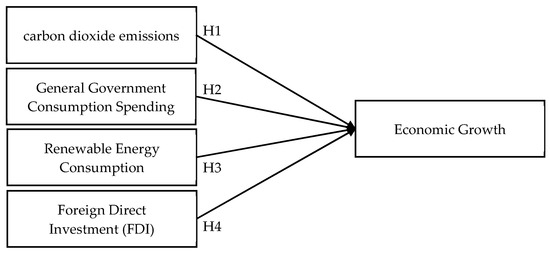

H1:

CO2 (metric tons per capita) has an adverse effect on EG.

H2:

REC (percentage of total final energy consumption) boosts EG.

H3:

GGCS (percentage) has a positive impact on EG.

H4:

FDI, net inflows (% of GDP) negatively influence EG.

2.2. Justification of Choice of Variables

Three theoretical, empirical, and contextual considerations justify the inclusion of variables in this economic model. In line with the principles of growth theory, GDP per capita, broadly recognized as a conventional indicator of economic performance, is chosen as the dependent variable. Moreover, the analytical framework, which combines Pedroni’s extension of the Cobb–Douglas production function with Keynesian theory, directs the independent variable selection [19]. Furthermore, renewable energy consumption (REC) and carbon dioxide emissions denote key energy and environmental factors necessary for identifying contemporary growth determinants. Likewise, foreign direct investment (FDI) is considered for its potential to boost technology transfer and capital accumulation, as pointed out in endogenous growth theories. Additionally, government final consumption expenditure (GGCS), a main element of Keynesian fiscal policy, is incorporated for its impact on global demand. This rationale is empirically supported by a series of diverse studies, some of which have been conducted in the Moroccan context and comparable economies, thus confirming both the relevance and explanatory power of the proposed variable set. The proposed conceptual framework aligns with Morocco’s strategic priorities, which seek to balance economic growth, energy security, investor attractiveness, and fiscal stability. In this manner, such variable choice provides the analysis with both political and practical significance and relevance.

The theoretical framework is further enriched through the integration augmented production function. It clearly encompasses energy as a production input, alongside Keynesian mechanisms linking aggregate global demand to economic growth [20]. Additionally, this integration facilitates the development of coherent and theoretically grounded hypotheses. The anticipated positive effect of carbon dioxide emissions reflects the industrial activity in a growth phase that is not yet decoupled from environmental costs; the benefits of utilizing renewable energy accord with the theories of ecological modernization and enhance energy efficiency, and the adverse effects of public consumption expenditures reflect concerns regarding the crowding out of private investment or inefficient resource allocation. Furthermore, the ambiguity surrounding the expected impact of FDI represents a theoretical discourse on technology transfer and the pollution haven hypothesis, thereby offering a strong integrated conceptual foundation for empirical investigation. This theoretical paradigm unleashes fruitful and beneficial insights for shaping national economic and energy policies.

Based on the above argument, this study provides some important empirical and contextual contributions, underpinned by a thorough methodology. It employs the ARDL model to jointly examine the dynamic relationships between the five key variables, carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption, foreign direct investment, government expenditure, and economic growth, within the Moroccan context over the period 1993–2020. Despite the strong establishment of the ARDL approach in the academic literature, its application to this specific configuration of variables in the Moroccan setting constitutes an innovative contribution. As such, this research bridges a salient empirical gap through robust assessments of both the short- and long-term dynamics of the Moroccan economy.

This paper aims to investigate the relationship between Morocco’s economic development (EG) capacity and carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption, and government expenditure. Consequently, the following hypotheses are explained, along with the conceptual model, as shown below, but before this, we will show table of abbreviation (see Table 1) and data source (see Table 2), so.

Table 1.

Abbreviation list.

Table 2.

Variable descriptions.

- ➢

- FDI → economic growth (+)

Theory: Endogenous development and technological transmission.

The endogenous growth theory reinforced that economic growth results from internal factors that are integrated into the production process rather than solely being attributed to exogenous factors, as postulated in neoclassical models [21,22]. This framework stresses the critical role of knowledge capital, which embraces technological progress, innovation, and human capital as the fundamental drivers of sustained long-term growth. It points out the positive externalities and spillover effects that transform knowledge investments into public goods, generating stable or increasing returns to scale, in contrast to the diminishing returns associated with physical capital accumulation. According to this theoretical perspective, technology diffuses through multiple interconnected channels. First, research and development expenditure generates substantial organizational and technical knowledge. Second, human capital enhancement through education and training strengthens the capacity to adapt and integrate advanced technologies. International knowledge diffusion is particularly critical for developing economies, incorporating international trade; technology licensing; and, most importantly, foreign direct investment (FDI). These mechanisms are essential for transferring and embedding cutting-edge technologies, managerial strategies and practices, and quality standards within the host country’s production system.

- ▪

- The underlying rationale is that foreign direct investment encourages both capital accumulation and skill transfer, thereby accelerating the technological catch-up process and fostering sustainable economic development.

- ➢

- REC → economic growth (+)

Energy security constitutes a fundamental pillar of economic stability and subsequently refined through the contributions of the World Energy Council [23]. energy security depends upon continuous access to energy resources at affordable prices. Renewable energy enhances the resilience of production systems by reducing vulnerability to petroleum crises and geopolitical instability [24]. This perspective is consistent with findings from the IEA research program on sustainable energy security, demonstrating that energy stability reduces investor uncertainty and strengthens industrial planning capacity. The shift to sustainable development through his framework serves as a catalyst for economic modernization [25]. seminal work on the Porter Hypothesis proves how environmental regulations foster innovation and strengthen competitive advantage [26]. This transition generates economies of scale by decreasing the costs of renewable energy (as documented in IRENA’s comprehensive 2021 study) and elevates the overall productivity via improved energy efficiency, thereby supporting the OECD’s theoretical growth framework.

- ▪

- In other words, maximizing the use of renewable energy boosts productivity while minimizing reliance on external energy sources.

- ➢

- CO2 → economic growth (+/−)

Kuznets’ theory of the environmental curve (CKE)

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis posits an inverted U-shaped relationship between environmental degradation and per capita income [27,28]. Accordingly, industrialization and economic development lead to increased carbon dioxide emissions and other pollutants during the early stages of economic growth (the ascending portion of the curve). The transitional dynamics attributes this pattern to the prioritization of rapid industrial growth, often at the expense of environmental consideration [29]. The theoretical foundations of the inverted curve are found in multiple mechanisms [30,31]. Beyond a specific income threshold, evolving societal preferences catalyzed by technological progress and human capital accumulation ease the implementation of more rigorous environmental regulations and a shift toward a service-oriented economy. Theoretically, the simultaneous achievement of declining carbon dioxide emissions and continued economic growth becomes possible through the confluence of technological innovation, structural transformation, and societal demand for environmental quality. This assumption aligns with meta-analytical synthesis of empirical EKC research [32].

- ▪

- This theme reflects an ambiguous relationship that highlights the balance between environmental preservation and economic progress.

- ➢

- GGCS → economic growth (−)

Theory: Repression of private investment (anti-Keynesian).

The crowding-out hypothesis of public expenditure suggests that increased government consumption spending may reduce private investment through multiple channels [33,34]. On the one hand, public loans can drive interest rates upward (the financial crowding-out effect), hence raising the cost of credit for private organizations. On the other hand, non-productive public spending may divert scarce resources, including physical capital and skilled labor, from the private sector toward less efficient uses empirical analysis of public spending composition [35]. Beyond the direct crowding-out effects, research underlines that GGCS may contribute substantially to economic distortions [36,37]. Public spending that prioritizes current consumption over productive investment may hinder work and innovation incentives that result in economic rents and promote inefficient resource distribution. This perspective parallels New Keynesian economic theory which acknowledges that certain forms of public spending may produce market rigidities and inefficiencies, constraining long-term growth potential [38].

- ▪

- This concept suggests that public spending can potentially reduce economic efficiency.

3. Data and Methodology

Our research framework is based on a Cobb–Douglas energy production function, Y = f(K, L, E), where energy (E) is explicitly incorporated as a production element alongside capital (K) and labor (L), methodological approach. Keynesian principles related to government spending complement this neoclassical foundation [19]. The transmission channels are well established: the use of renewable energy (REC) promotes growth by enhancing productivity and improving energy security; carbon dioxide emissions reflect the effects of industrialization and reliance on fossil fuels; foreign direct investments (IDEs) stimulate growth through technology transfer and capital accumulation; and public spending (GGCS) affects global demand and allocation efficiency. This integrative framework enables the simultaneous analysis of supply-side production and the demand side within the context of Morocco’s economic development process.

Following the methodology this study employs the ARDL model for estimation. In cases where the application of the existence of a single cointegrating vector is impractical, the researchers proposed a way to cointegrate a bound technique for long-term relationships. This technique is called autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and is particularly advantageous, as it ignores the stationarity of the variables [39]. Nevertheless, ARDL yields more accurate, efficient, and consistent estimates. Lastly, the variables’ model’s short-run and long-run link definitions are produced by ARDL parameterization results.

Originally the ARDL approach is used in this study to investigate correlations between LT (long-term) and ST (short-term) variables with different orders of integration. ARDL is particularly suitable for small sample sizes and mixed orders of integration, whether I(0) or I(1), and provides robust long-run estimates [1,40]. The optimal lag structure (p, q) for our model is determined by applying the Hannan–Quinn, Schwarz (SIC), and Akaike (AIC) information criteria [1]. The proposed model is based on a larger corpus of literature. In addition, the empirical analysis relies on annual data for Morocco covering the period 1993–2020, obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database. The variables selected are based on previous research relevant to energy, the environment, and growth relationships. Within the Keynesian growth framework, government expenditure plays a vital role in sustaining long-term economic expansion [6]. As per the Keynesian paradigm, sustained economic growth is enhanced by the rise of government expenditure. Accordingly, this study integrates this perspective into a Cobb–Douglas production framework. extends the model by incorporating energy as a productive input, such that , where represents the energy input necessary for growth [19,20]. Based on this theoretical foundation, the study model is as follows:

where Y is GDP per capita, REC, CO2 emissions, FDI, and GGCS.

Y = f (FDI, CO2 emissions, REC, GGFCS),

The research model was developed by blending theory and practice. It draws on the traditional practice of the conditional convergence model using the GDP per resident as the absolute value rather than the growth rate [41]. The starting GDP per resident affects the development axis in these models. Likewise, which extends the Solow model, the transition from the theoretical model of production, Y = F(K,L,S), to the empirical model is accomplished through typical logarithmic linearization [42]. The logarithmic method transforms the Cobb–Douglas equation, Y = AK^αL^βS^γ, into a linear form: ln(Y) = ln(A) + αln(K) + βln(L) + γln(S). In this context, the institutional (FDI, GGCS) and energy (REC, carbon dioxide emissions) variables are considered components of total factor productivity, , consistent which integrates non-traditional factors into production functions. Consequently, the model can be expressed as

where the stochastic disturbance term is denoted by ε.

GDP per capitat = α0 + α1FDIt + α2CO2 emissionst + α3RECt + α4GGFCSt + εt

To summarize, the ARDL approach provides an appropriate framework for this study’s estimation strategy. By accommodating variables with different orders of integration and distinguishing between short-run and long-run dynamics, the ARDL model enables a holistic view of Morocco’s growth determinants, consistent with the theoretical foundations of the Keynesian and neoclassical growth paradigms.

4. Results of the Study

This section examines the long- and short-run relationships between GDP per capita, FDI, carbon dioxide emissions, GGCS, and REC in Morocco using the ARDL cointegration approach. At this stage, location, dispersion, and normalcy indicators are computed, and the relevant data are extracted and analyzed. The results of these computations, obtained using EViews 12, are presented in the table below.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

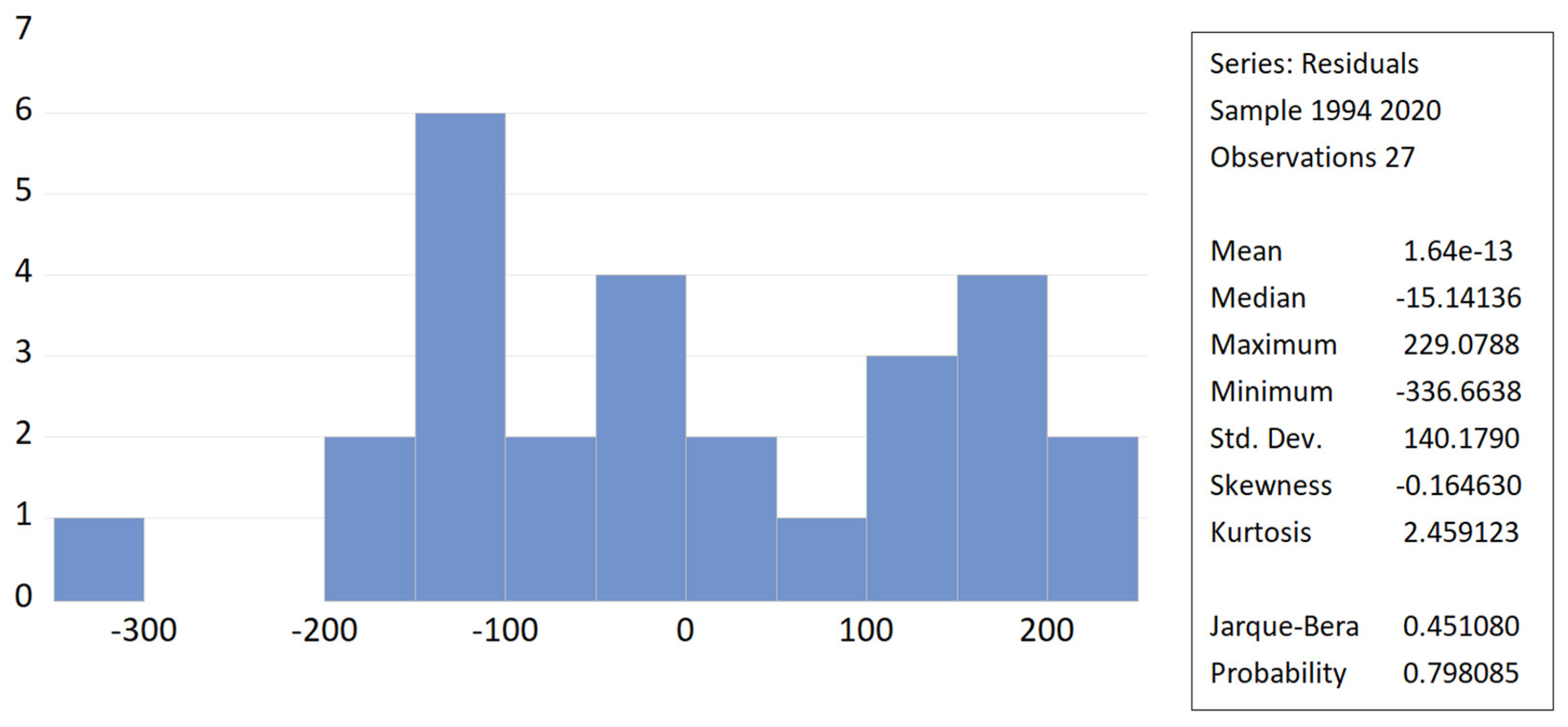

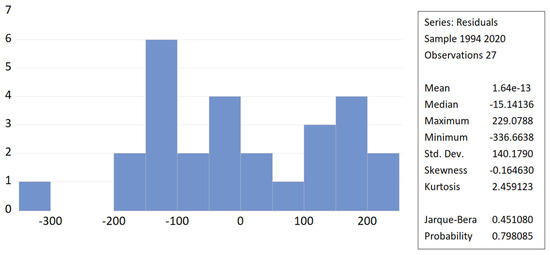

From statistical and economic viewpoints, the descriptive analysis reveals interesting, noteworthy features. GDP per capita exhibits a mean value of approximately USD 2460, with a wide dispersion (écart-type standard deviation of 833.8). The distribution has fairly good symmetry (asymmetry close to zero; skewness close to zero) yet is notably flat (kurtosis below three), indicating a platykurtic shape. Foreign direct investment (FDI) shows a strong probability of extreme values (kurtosis high at 6.43) and a strongly right-skewed distribution (skewness = 1.5; asymmetry = 1.5). This deviation from normality is confirmed by the Jarque–Bera test, which rejects the null hypothesis of normality (p-value = 0.000005) as Shown in Figure 1. Also, CO2 emissions per capita remain relatively stable (low standard deviation of 0.2; low standard deviation 0.299), while both government spending (GGCS) and renewable energy consumption (REC) show globally normal distributions based on Jarque–Bera tests.

Figure 1.

Normality test.

From an economic perspective, these results reflect the evolution of the Moroccan economy. Despite some fluctuations, the rise in GDP per capita over the study period (from USD 1217 to USD 3498) suggests a robust economic boom. However, the significant fluctuation in FDI inflows (from 0.66 percent to 6.44 percent of the GDP) may indicate possible instability associated with reliance on foreign capital. In other words, the relative stability of CO2 emissions, despite continued economic expansion, could signal an early stage of decline. In addition, the percentage of renewable energy (from 10.45% to 22.97%) points to an ongoing energy transition. Although this average may conceal qualitative differences, the steady level of government spending at about 17% of GDP suggests a consistent budgetary approach. Overall, these findings portray an expanding economy that is progressively managing the balance between international competitiveness, development, and ecological transformation.

Statistically, GDP per capita (in current USD) demonstrates the highest volatility, while carbon dioxide emissions (in metric tons) exhibit the lowest variability, as indicated by their respective standard deviations. Furthermore, excluding the FDI variable, all other indicators (GDP, carbon dioxide emissions, REC, and GGCS) appear to follow approximately normal distributions, with Jarque–Bera probabilities exceeding 5%. In addition, the kurtosis coefficients for all variables (except FDI) are below three, indicating flatter distributions relative to the normal distribution.

4.2. Unit Root Tests

The results presented in Table 3 indicate that the model variables are stationary in initial difference, I(1). ARDL models are defined by a lag in delicate selection orders [43]. In this econometric evaluation, the optimal model was selected based on the lowest values of the Schwarz information criterion (SIC) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [1,44]. Moreover, general government consumption spending (GGCS), which increased throughout the study period (see Figure 2), had a significant influence on the Moroccan economy. Noticeably, Morocco’s renewable energy consumption (REC) declined between 2005 and 2011. A non-stationary series is one that exhibits a unit root [45]. Unit root (UR) tests are, therefore, applied to control the model’s integration directive for variables. The Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test was chosen for this purpose. The results show that carbon dioxide emissions are stationary at level , with a p-value of 0.0000, while all other variables become stationary after first differencing, . As a result, the ARDL framework was adopted, as it allows for the inclusion of variables integrated at different orders (I(0) and I(1)) within the same model.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model.

4.3. Co-Integration Bound Test and Optimal Lag

The maximum latency determined by the Final Prediction Error (FPE), Schwarz Bayesian information criterion (SBIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), and Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQIC) is reported in the table above. By comparing the minimum values of each criterion across successive lag orders, the optimal lag length was identified as 1 (662.4384 for FPE, 20.64299 for AIC, 22.09464 for SBIC, and 21.06101 for HQIC). The ARDL regression, estimated at the optimal lag length determined by the AIC, represents the initial stage of model estimation (see Table 2). The second stage involves assessing both (LR) and (SR) relationships among the variables (Table 4). The regression results reported in Table 5 indicate that carbon dioxide emissions and the proportion of final energy consumed that originates from renewable energy have positive effects on economic growth (EG), while GGCS has a statistically significant positive impact on the sustainability of EG. In contrast, foreign direct investment (FDI) has a negative impact on EG. Based on the long-run coefficients reported in Table 6, GGCS demonstrates a negative relationship with EG, whereas REC and carbon dioxide emissions display positive and significant effects. These findings are consistent with the results of [1,46]. The pace of the adjustment coefficient, reported in Table 6, is negative (−0.192027), indicating how quickly the equilibrium is distorted or how well the dependent variable reacts to the equilibrium relationship deviation in a particular period. Additionally, three positive short-run coefficients (781.0957, 11.39506, and 14.38036) are observed in the short-run link. This suggests that short-run fluctuations influence the model dynamics, while deviations from the long-run equilibrium are temporarily disregarded. Overall, these results confirm that the Moroccan economy exhibits both short-run responsiveness and gradual long-run convergence within the estimated ARDL framework.

Table 4.

Stationarity test.

Table 5.

Co-integration bound test and optimal lag.

Table 6.

ARDL regression.

The ARDL results demonstrate the complexity of Morocco’s economic dynamics over the study period. This significant persistence of the GDP per capita is demonstrated by the coefficient associated with the dependent variable, with a decline (GDP(−1)) in Table 5, which shows a positive value and is significant at the statistical level. Economically, this suggests that the income level in a given year is closely linked to that of the preceding year, confirming the relevance and robustness of the dynamic modeling approach.

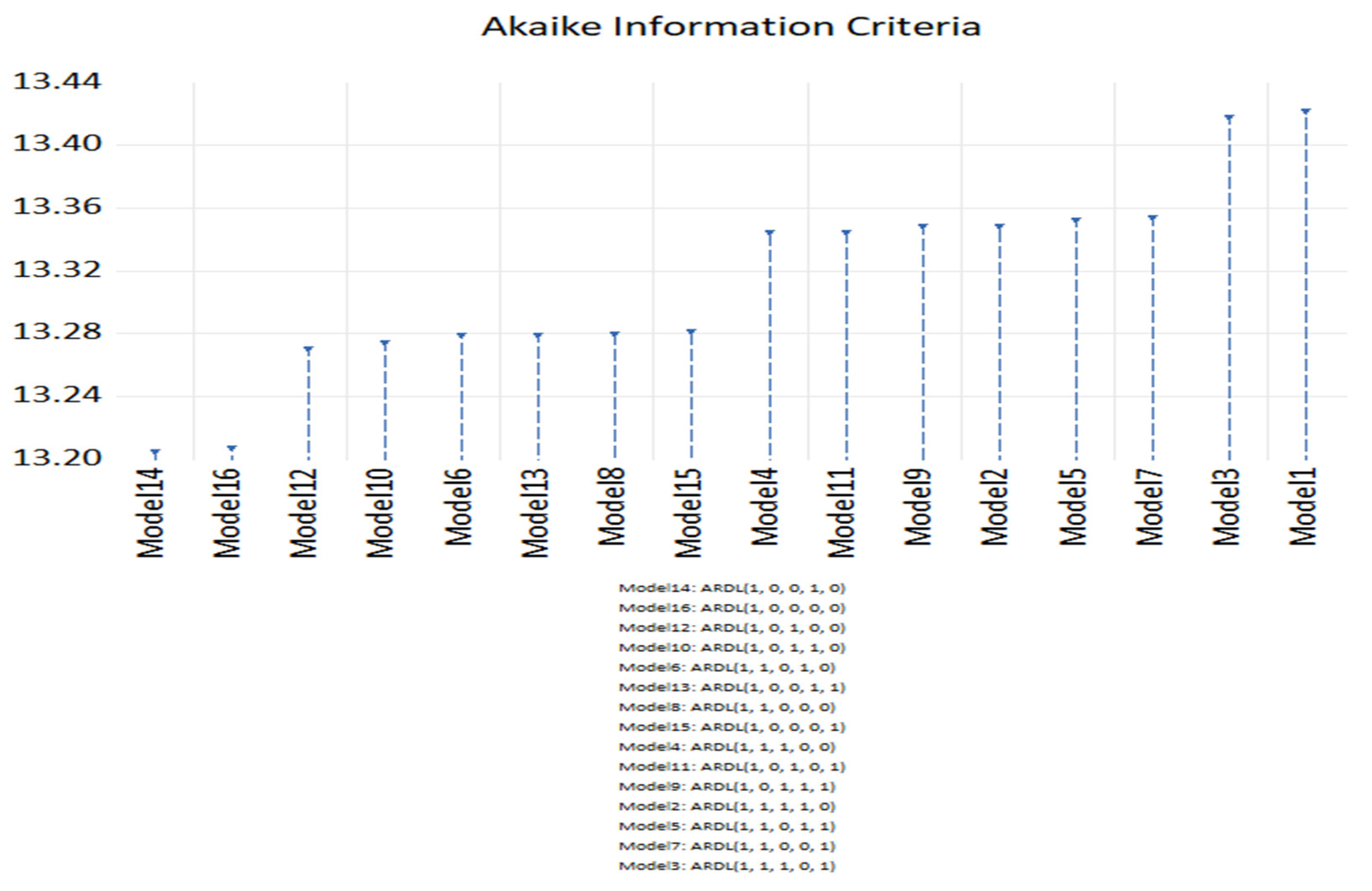

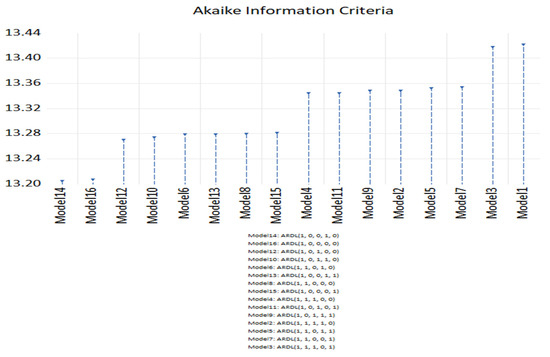

The Akaike information criterion (AIC) as a method to evaluate the performance and efficiency of statistical models [47]. Adding parameters during the model estimation process increases the model’s likelihood. Based on the results presented in Figure 3, the model with the lowest AIC value, Model 14 (1, 0, 0, 1, 0), was identified as the optimal specification for this analysis.

Figure 3.

Optimal lag selection.

4.4. Long-Run, Short-Run, and Adjustment Dynamics

See Table 7 below, shows the short run, Long run, and adjustment of this current research.

Table 7.

Results of ARDL short-run (SR), long-run (LR), and adjustment (ADJ).

It is essential to distinguish between statistical significance and economic relevance when interpreting empirical results [48]. Appropriately, the analysis of coefficient estimates extends beyond conventional significance thresholds to include economic meaning and theoretical consistency. Although only the carbon dioxide emissions variable is statistically significant at the 5% level, the direction and magnitude of the other coefficients remain consistent with prior research. The positive impact of renewable energy consumption (REC) is consistent with the meta-analyses of Saidi and Omri (2020) [49], where the negative effect of government green capital spending (GGCS) is consistent with [37]. The insignificance of foreign direct investment (FDI) reflects the complex and context-dependent nature of its effects in emerging economies that have been well documented in previous research. Both empirically and theoretically, the model is well supported, showing an adjustment rate of 19.2% per year (over a period of 3.3 years). More specifically, the results are in line with ARDL studies on developing nations that consistently show that the duration of demise for macroeconomic structural factors ranges from two to five years [50]. Furthermore, the moderate pace of adjustment observed underscores the intrinsically evolutionary nature of energy and institutional transformations within the Moroccan context, which is characterized by gradual changes (Vision 2010–2030) rather than economic revolutions. The findings support a nuanced interpretation that values both statistical robustness and economic coherence, rather than relying solely on strict significance criteria. Finally, as a cointegration technique, the ARDL bounds testing approach is applied to assess the existence of long-term relationships among the model variables [1,39].

The most important stage of the analysis involves confirming the cointegration of public revenue and expenditures to ascertain whether Morocco’s public debt can be maintained bounds cointegration test [1,39]. This test evaluates whether a long-run equilibrium relationship exists among the variables by comparing the computed F-statistic with the critical lower and upper bounds. Three outcomes are possible: (1) if the F-statistic exceeds the upper bound, the variables are cointegrated; (2) if the F-statistic lies between the lower and upper bounds, the result is inconclusive; and (3) if the F-statistic is below the lower bound, there is no evidence of cointegration. As reported in Table 8 (ARDL regression: bounds test results), the calculated F-statistic (F = 2.387734) exceeds the 10% significance level lower bound of 2.2, indicating the presence of a long-run cointegration relationship among the model variables. Thus, the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected, suggesting a stable long-term equilibrium between the exogenous and endogenous variables. Before validating the model, diagnostic tests were performed to assess heteroscedasticity and normality. Examining whether the variance in the residuals is constant across observations requires an understanding of heteroscedasticity. To discover this, the White test, which is based on the Chi-square distribution, can be applied alongside other diagnostic methods. The results indicate the absence of heteroscedasticity, confirming that the residuals are normally distributed.

Table 8.

ARDL regression: bounds test results.

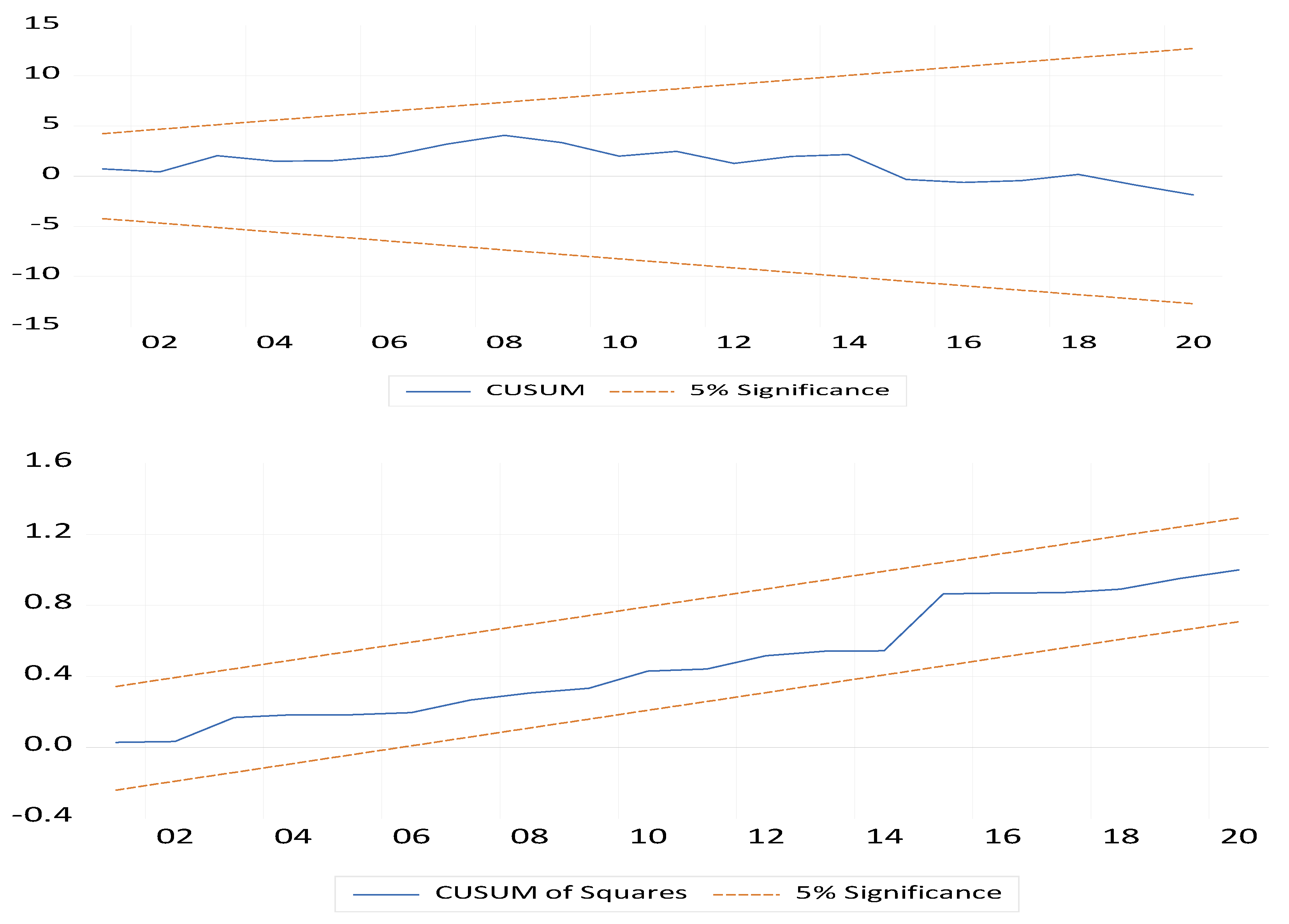

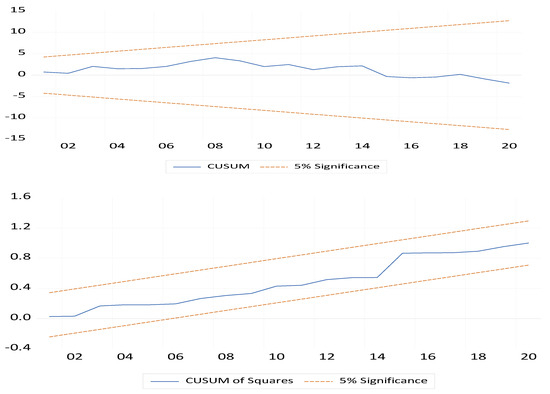

4.5. Test of Heteroscedasticity and CUSUM of Squares

To construct prediction intervals and conduct Student’s t-tests for parameter significance, it is essential to verify the normality of the error terms. The Jarque–Bera test illustrates how to use the notions of skewness (asymmetries) and kurtosis to confirm if a statistical distribution is normal [51,52]. Since the Jarque–Bera probability value of 45.10% exceeds the 5% threshold, the residuals can be considered white Gaussian noise following a normal distribution. This confirms the assumption of normality. In addition, the CUSUM of Squares test is considered the most appropriate tool for assessing model stability. This test plots two boundary lines that define the confidence interval and trace the cumulative sum of the squared residuals. It may be said that based on the graph results, the CUSUM and CUSUM of Squares plots remain within the critical limits, indicating that the estimated model is stable and that the coefficients remain constant over time. Further, the results confirm the existence of a long-run (LR) relationship between the exogenous and endogenous variables, namely, renewable energy consumption (REC), government green capital spending (GGCS), and carbon dioxide emissions—as demonstrated in previous research [1,46]. Additionally, the findings support the positive long-term effects of CO2 emissions and REC on Morocco’s economic growth, which is consistent with [1,46]. Consequently, hypotheses H2 and H3 are confirmed. Similarly, the study reveals a negative effect of GGCS on Morocco’s economic growth, which aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. (2021) and Connolly and Li (2016), thereby supporting H1 [17,18]. Likewise, foreign direct investment (FDI) strongly affects environmental situations while fostering economic growth [15]; hence, H4 is accepted. And Table 9 shows white test.

Table 9.

White’s test: Heteroscedasticity.

The CUSUM of Squares test, along with the CUSUM graph, which is based on the cumulative sum of the squared recursive residuals plotted between two boundary lines representing the confidence interval, is the most appropriate tool for assessing the stability of the model. It can be concluded that the estimated model is stable based on the graph, which displays the CUSUM of Squares test results (see Figure 4), in that the curve remains within the dotted boundary lines. Consequently, the coefficients remain consistent over time. Overall, the results of the various diagnostic tests confirm the validity of our ARDL model (1, 0, 0, 1, 0).

Figure 4.

Parameter stability: CUSUM of Squares test.

5. Discussion

Empirical studies investigating the relationships between renewable energy consumption (REC), carbon dioxide emissions, general government final consumption spending (GGCS), and economic growth (EG) have revealed important disparities. The results demonstrated how these variables’ interactions have evolved over time. These findings validate Keynes’s central hypothesis, which put forward a significant positive correlation between GGCS and EG [53]. However, this study’s results oppose the Keynesian hypothesis by showing that the general government expenditure negatively impacts EG. These findings complement Zhang et al. (2021) and Connolly and Li (2016), which may relate to deficiencies in the research and development process. According to Zhang et al. (2021), government support for scientific research and development is critical to sustaining EG [17,18]. Also, the study’s results showed that REC and carbon dioxide emissions display positive correlations and support economic growth. This confirms the previous findings of Hanadi Taher (2024) and corroborates Bouyghrissi et al. (2021), who stated that combining EG and energy demonstrates positive long-term cointegration [8,46]. Empirical findings by Bouyghrissi et al. (2021) indicate that Morocco’s renewable energy utilization is starting to yield positive effects, assuming the existence of a causal relationship between RE consumption and both EG and carbon dioxide emissions [8]. On another note, regarding the financial dimensions of sustainable development, the study examined the effect of carbon dioxide emissions, REC, and GGCS on Morocco’s capacity to achieve sustainable economic growth from the period of 1993 to 2020. However, foreign direct investment (FDI) also promotes EG and significantly impacts environmental conditions [15]. The econometric analysis’s initial step involved confirming stationarity. The series remains stationary once the unit root test results are exposed at the first difference.

Using ARDL estimation, the study discovered that, based on GDP per capita, REC has a negative effect on EG in the first lag, while REC showed a significant positive impact on carbon dioxide emissions. The long-run coefficients validated the existing literature by showing that carbon dioxide emissions and GGCS exert considerable positive influences on Moroccan economic growth, whereas GGCS demonstrates a positive effect. Moreover, the short-run relationship reveals two positive coefficients. This suggests that long-run equilibrium nonconformities are disregarded, and only short-term fluctuations are taken into consideration. The research findings show how essential Morocco’s reliance on REC is in sustaining EG. To improve economic well-being, Moroccan policymakers should prioritize promoting renewable energy sources and strengthening carbon dioxide emissions regulations, despite the latter’s positive effect on EG and utility as an indicator of economic productivity. Given the harmful impact of the Moroccan government’s spending on EG, questions regarding the allocation of GGCS in general and its diversion from research and development specifically have to be raised. It is recommended to revise the Moroccan government’s policies to prioritize long-term sustainability, stressing government investment in R&D rather than consumption. Economic growth contributes to sustainable development, according to Fikri and Rhalma (2024) [1]. The concept of “sustainable development” embodies a widely held philosophy highlighting a balance between human needs, economic advancement, environmental preservation, and social harmony. Remarkably, strategies that might be considered beyond those presented in various media need not ultimately constrain expansion to the point of environmental crisis. Extensive research discusses sustainable development, with numerous organizations, institutions, and social structures advocating its adoption. It is believed that everyone should have access to the environment as a shared resource that does not cost anything. This costless approach has resulted in natural resource exhaustion and climate change, with both presenting major challenges to aspirations for long-term EG. However, sustainable development demands proper valuation of human capital according to Fikri and Rhalma (2024) [1].

Moving beyond straightforward statistical analysis, examining the results from economic and political perspectives reveals fruitful implications for Morocco. The positive correlation between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth underscores the main challenge of energy transition. On the one hand, Morocco’s economy depends on high-carbon activities for growth, necessitating strategies targeted at economic diversification and investment in low-carbon technologies to prevent decoupling. On the other hand, GGCS’s detrimental effects on economic growth underscore the need for profound budgetary reform to redirect expenditures from present spending toward productive investments in infrastructure, R&D, and human capital. The rationale behind the acceleration of national strategies like Noor and green hydrogen is justified by renewable energy’s (REC) benefits, which integrate and interrelate with industrial policies aimed at creating value and employment chains. In conclusion, these findings lay the groundwork for a new integrated economic approach wherein environmental sustainability and public financial efficiency become complementary, rather than antagonistic, instruments for robust growth.

Policy Recommendations

Establishing a beneficial relationship between carbon dioxide emissions and growth mandates a strategic carbon reduction policy targeting the most polluting sectors while preserving the economy. The stated advantages of renewable energy usage validate the acceleration of national initiatives, such as Noor and green hydrogen, within a competitive industrial framework. Conversely, the negative effects of public consumption expenditures stress the need for budgetary reform aimed at redirecting them toward profitable investments in human capital, R&D, and infrastructure. These consequences, nevertheless, remain contingent upon the methodological constraints of the causal inference analysis of this study.

This research goes beyond a straightforward assessment of growth by incorporating sustainable durability as a main factor in result interpretation. Drawing upon Pedroni’s (2004) work, the explicit integration of renewable energy consumption and CO2 emissions as productive factors in expanding the production function constitutes a conceptual advancement that directly articulates economic performance and its environmental constraints [19]. The principal finding regarding emissions’ positive growth effect is interpreted not as a normative conclusion but rather as evidence of the Moroccan economy’s inherent reliance on fossil fuels, which is a critical component of its ecological transformation. Simultaneously, the benefits accompanying renewable energy highlight the viability of a progressive decline. The political discussion that follows focuses specifically on the prerequisites for long-term growth, advocating for reorientation of public investments in favor of low-carbon innovation while emphasizing the central role of national programs like Noor. Therefore, sustainable durability is not merely an outward appearance; rather, it serves as the guiding principle and analytical foundation for the evaluation of the Moroccan economic dynamics. The short-term positive correlation between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth is strictly interpreted as evidence of a structurally persistent reliance on fossil fuels, reflecting the current state of industrial development in Morocco. Conversely, the statistically significant positive effect of renewable energy demonstrates the economic feasibility of an energy transition and its potential contribution to a progressive disengagement between growth and emissions. These empirical findings are consistently linked to environmental policy challenges, such as the necessity of redirecting public spending toward ecological infrastructure and reforming environmental fiscality to include carbon costs. This provides a robust analytical framework for directing national development strategies with low carbon emissions.

Although the focus of this study is primarily economic, its ramifications can be directly integrated into Morocco’s environmental commitments and Sustainable Development Goals. The empirical evidence concerning renewable energy and carbon dioxide emissions effects provides quantifiable metrics for SDG 7 (access to one’s own energy) and SDG 8 (quality and economic development), whereas the public expenditure analysis provides insights relevant to SDG 9 (innovation and infrastructures). Investment directed toward renewable energy sources represents a cornerstone of Morocco’s energy transition strategy and helps with the implementation of its CDN (Contributions Determined at the National Level) within the framework of the Paris Agreement. This research study incorporates sustainability as an interconnected paradigm within socio-theoretical frameworks. An important social dimension concerns how different energy policies affect economic growth and job creation in the environmental sector. Though not explicitly stated, this research guides the evaluation of trade-offs between economic, environmental, and social goals. This approach aligns with the holistic approach of sustainable durability science, which acknowledges the indivisibility of these three pillars.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the effects of carbon dioxide emissions, renewable energy consumption, foreign direct investment, government general consumption spending, and economic growth in the Moroccan context spanning 1993 to 2020. The empirical results illustrate that carbon dioxide emissions and renewable energy have positive effects on economic growth, whereas government general consumption spending manifests a negative relationship, contradicting Keynesian theoretical expectations. With stable and normally distributed residuals, the ARDL methodology validates a long-run equilibrium relationship between the variables. These findings present the significance of sustained energy policies while questioning the efficiency and effectiveness of government general consumption spending. This investigation acknowledges limitations. Notwithstanding its temporal scope, the analysis period precludes capturing the effects of recent Moroccan renewable energy consumption reforms. Moreover, the exclusion of institutional or geopolitical determinants may affect the observed relationships. Finally, while the economic framework is rigorous, it overlooks external factors that could influence the dynamics under study, like global crises or fluctuations in the price of petroleum. In order to facilitate regional comparisons, future research should extend the analysis to other African countries. Equally, the incorporation of additional variables, including technological innovation or institutional quality, would enable refinement of the conclusions. The robustness of the results could also be strengthened through a panel dynamic approach. Furthermore, qualitative investigation, including interviews with policy decision-makers, could shed light on the mechanisms underlying the observed relationships. Finally, a more comprehensive sectoral analysis of public spending across infrastructure, healthcare, and education would have facilitated the identification of the areas where government involvement is most effective for long-term sustainable growth. These research directions would enable better orientation of Morocco’s economic and environmental policies within the context of the global energy transition. Despite the undeniable methodological advantages of the ARDL framework for this analysis, it does have noteworthy limitations. Firstly, its capacity to accommodate integrated variables of the order I(0) or I(1) becomes a significant disadvantage when confronting series stationary at I(2), which it cannot incorporate. Secondly, the selection of the number of delays (p; q) and the different information criteria (AIC; SIC) may lead to the divergence of model specifications, potentially compromising the reliability and robustness of the results. Conversely, although the ARDL model is relatively more effective than other alternative cointegration techniques, operating with a small sample size (28 observations) limits the precision and accuracy of estimators and the solidity of statistical tests. Ultimately, the ARDL model does not directly allow for the identification of multiple simultaneous cointegration relationships, which represents a structural limitation in size given the hypothesis that our variables may theoretically exhibit several long-run equilibria.

Limitations and Future Research

It is imperative to acknowledge some limitations in this research. Despite three decades of coverage, the analysis remains insufficient in fully capturing the effects of recent energy reforms in Morocco, like green hydrogen initiatives. Moreover, the analysis is constrained by data availability and may be influenced by the absence of institutional or geopolitical determinants that shape the observed dynamics. Furthermore, while the ARDL methodology is sound, its application to a small sample size (28 observations) may hinder the estimators’ effectiveness. Lastly, this approach does not directly address concerns related to missing variables or inverse causality.

This research opens up a number of prospective research directions, including extending the analysis to several African countries that share comparable characteristics with Morocco in an effort to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, incorporating other institutional variables, such as effectiveness of governance and corruption indices, and technological determinants, such as R&D expenditures and environmental patents, would facilitate the identification of critical mechanisms that underpin the observed relationships. Finally, the application of causal identification techniques, including instrumental variables or double differences, to specific policy reforms, coupled with sector-by-sector analysis, would strengthen our understanding of the mechanisms governing Morocco’s energy transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F.; Methodology, Y.F.; Validation, Y.F.; Software, Y.F.; Formal Analysis, Y.F.; Investigation, Y.F.; Resources, Y.F.; Data Curation, Y.F.; Writing—Original Draft preparation, Y.F.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.F., R.T., A.S., A.H. and A.K.; Supervision, Y.F.; Project Administration, Y.F.; Funding Acquisition, Y.F., R.T., A.S., A.H. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fikri, Y.; Rhalma, M. Effect of CO2 Emissions, Renewable Energy Consumption and General Government Final Consumption Spending on Moroccan Economic Growth: ARDL Approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Samman, H.; Akkaş, E. How Do the Crises of Falling Oil Prices and COVID-19 Affect Economic Sectors in the Rentier Economies? Evidence from the GCC Countries. J. Econ. Cult. Soc. 2022, 65, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swe, H.Y. Analysis of Long Run and Short Run Relationship between Myanmar’s Economy and Infrastructure-Social Investment; Myanmar. 2019. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/analysis-of-long-run-and-short-run-relationship-between-3222o7lrz2 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Batool, K.; Akbar, M. Influence of Infrastructure Development with Its Sub-Sectors on Economic Growth in Selected Asian Countries: An Empirical Analysis Using DOLS and FMOLS Approaches. Pak. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 11, 2236–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbal, A.; Khihel, F. The Impact of Interactions Between Public and Private Investment on Improving the Business Climate in Morocco; International Journal of Accounting, Finance, Auditing, Management and Economics. 2023. Available online: https://ijafame.org/index.php/ijafame/article/view/858/857 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Meltzer, A.H. Keynes’s General Theory: A Different Perspective. J. Econ. Lit. 1981, 19, 34–64. [Google Scholar]

- El Asli, H.; Hamid, L.; Zineb, A.; Mohamed, A. Impact of Human Capital, Economic Factors, Energy Consumption, and Urban Growth on Environmental Sustainability in Morocco: An ARDL Approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyghrissi, S.; Berjaoui, A.; Khanniba, M. The Nexus between Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in Morocco. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 5693–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, T.; Valdés, L.; Zheng, Y. Supply Chain Visibility and Social Responsibility: Investigating Consumers’ Behaviors and Motives. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2018, 20, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, T.; Valdés, L.; Zheng, Y. Consumer Trust in Social Responsibility Communications: The Role of Supply Chain Visibility. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 4113–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth Nexus: Evidence from a Threshold Model. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, H. Renewable Energy Consumption Impact on the Lebanese Economy. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2017, 7, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, R.A.; Sohag, K.; Abdullah, S.M.S.; Jaafar, M. CO2 Emissions, Energy Consumption, Economic and Population Growth in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Begum, R.A.; Said, M.N.M.; Pereira, J.J. Relationship between Economic Growth, Renewable Energy Use, Technological Innovation, and Carbon Emission toward Achieving Malaysia’s Paris Agreement. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2022, 42, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; An, Y.; He, F.; Goodell, J.W. Do FDI Inflows Bring Both Capital and CO2 Emissions? Evidence from Non-Parametric Modelling for the G7 Countries. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, M.; Sanchez-Robles, F.D.I. Economic Freedom, and Growth: New Evidence from Latin America. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2003, 19, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Mohsin, M.; Rasheed, A.K.; Chang, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Public Spending and Green Economic Growth in BRI Region: Mediating Role of Green Finance. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; Li, C. Government Spending and Economic Growth in the OECD Countries. J. Econ. Policy Reform. 2016, 19, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. Econ. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josheski, D.; Lazarov, D.; Koteski, C. Cobb-Douglas Production Function Revisited, VAR and VECM Analysis and a Note on Fischer/Cobb-Douglass Paradox. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E., Jr.; Prescott, E.C. Investment under Uncertainty. Econometrica 1971, 39, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, D. The Economics of Public Utility Regulation. J. Political Econ. 1941, 49, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yergin, D. Ensuring Energy Security. Foreign Aff. 2006, 85, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, T. Empirical Tests and Policy Analysis of Environmental Degradation at Different Stages of Economic Development; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis: A Survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Laplante, B.; Wang, H.; Wheeler, D. Confronting the Environmental Kuznets Curve. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. The Rise and Fall of the Environmental Kuznets Curve. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1419–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.T. The Environmental Kuznets Curve: Seeking Empirical Regularity and Theoretical Structure. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Limitations of Tax Limitation. Policy Rev. 1978, 5, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.J. Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, S103–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, D.A. Is Public Expenditure Productive? J. Monet. Econ. 1989, 23, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, K.B.; Tullock, G. An Empirical Analysis of Cross-National Economic Growth, 1951–1980. J. Monet. Econ. 1989, 24, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, S.; Swaroop, V.; Zou, H. The Composition of Public Expenditure and Economic Growth. J. Monet. Econ. 1996, 37, 313–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G. A Quick Refresher Course in Macroeconomics. J. Econ. Lit. 1990, 28, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. An Autoregressive Distributed Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis; Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Convergence. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G.; Romer, D.; Weil, D.N. A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. A Simple Estimator of Cointegrating Vectors in Higher Order Integrated Systems. Econometrica 1993, 61, 783–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.G.; Wuttke, D.A.; Ball, G.P.; Heese, H.S. Does Social Media Elevate Supply Chain Importance? An Empirical Examination of Supply Chain Glitches, Twitter Reactions, and Stock Market Returns. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 646–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yule, G.U. Why Do We Sometimes Get Nonsense-Correlations between Time-Series? A Study in Sampling and the Nature of Time-Series. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1926, 89, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, H. The Impact of Government Expenditure, Renewable Energy Consumption, and CO2 Emissions on Lebanese Economic Sustainability: ARDL Approach. Environ. Econ. 2024, 15, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Canonical Correlation Analysis of Time Series and the Use of an Information Criterion. Math. Sci. Eng. 1976, 126, 27–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA Statement on P-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. Am. Stat. 2016, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, K.; Omri, A. The Impact of Renewable Energy on Carbon Emissions and Economic Growth in 15 Major Renewable Energy-Consuming Countries. Env. Res. 2020, 186, 109567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Dolado, J.; Mestre, R. Error-Correction Mechanism Tests for Cointegration in a Single-Equation Framework. J. Time Ser. Anal. 1998, 19, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.K.; Jarque, C.M.; Lee, L.-F. Testing the Normality Assumption in Limited Dependent Variable Models. Int. Econ. Rev. 1984, 25, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R. Prévision Des Ventes. Polycopié Du Produit Multimédia, Université Paris-Dauphine, Editor: Librairie Eyrolles—Paris 5e, France. 2001. Available online: https://moodle.luniversitenumerique.fr/pluginfile.php/4260/mod_resource/content/0/poly.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Pigou, A.C. Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Economica 1936, 3, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).