Comparative Analysis of MCDI and Circulation-MCDI Performance Under Symmetric and Asymmetric Cycle Modes at Pilot Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

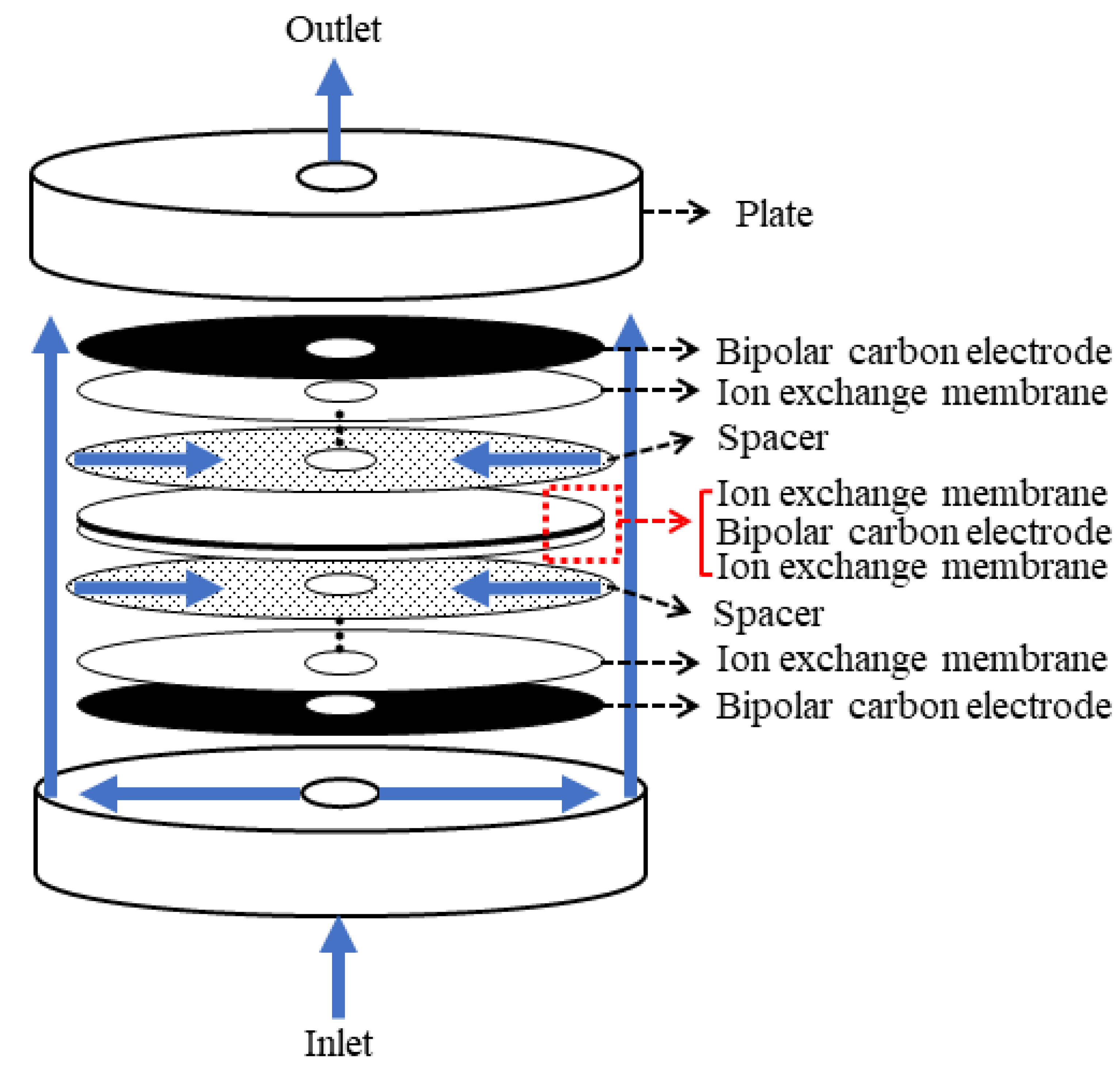

2.1. MCDI Module

2.2. MCDI Pilot Unit and Operation Conditions

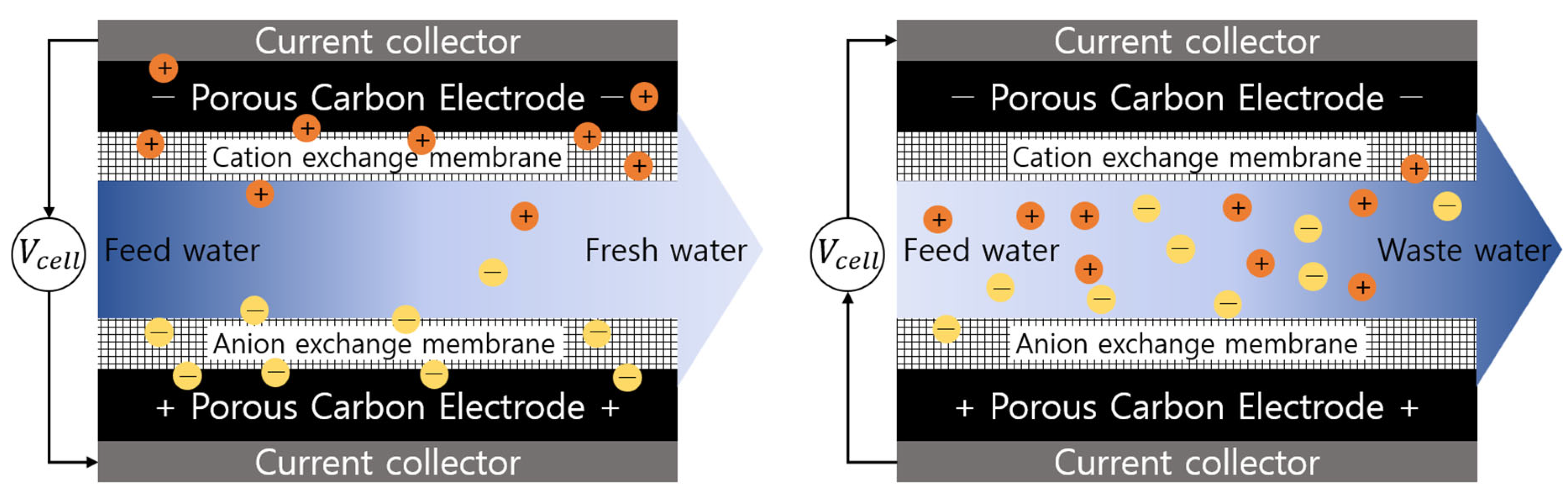

2.3. MCDI & Circulation MCDI Process

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Variations in Electrical Conductivity According to Adsorption/Desorption Time

3.2. Removal Efficiency and Energy Consumption Under Symmetric Conditions

3.3. Removal Efficiency and Energy Consumption Under Asymmetric Conditions

3.4. Determination of Optimal Operating Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruiz-García, A.; Nuez, I. Long-term intermittent operation of a full-scale BWRO desalination plant. Desalination 2020, 489, 114526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porada, S.; Zhao, R.; Van Der Wal, A.; Presser, V.; Biesheuvel, P.M. Review on the science and technology of water desalination by capacitive deionization. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2013, 58, 1388–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddonetto, T.L.; Deemer, E.; Lugo, A.; Cappelle, M.; Xu, P.; Santiago, I.; Walker, W.S. Assessment of salt-free electrodialysis metathesis: A novel process for brine management in brackish water desalination using monovalent selective ion exchange membranes. Desalination 2024, 592, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liang, D.; Lu, S.; Wang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Aurbach, D.; Avraham, E.; Cohen, I. Advances and perspectives in integrated membrane capacitive deionization for water desalination. Desalination 2022, 542, 116043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Sheng, L.; Wu, T.; Huang, L.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Research progress on the application of carbon-based composites in capacitive deionization technology. Desalination 2025, 593, 118197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufiani, O.; Tanaka, H.; Teshima, K.; Machunda, R.L.; Jande, Y.A.C. Capacitive deionization: Capacitor and battery materials, applications and future prospects. Desalination 2024, 587, 117923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauk, M.; Folaranmi, G.; Cretin, M.; Bechelany, M.; Sistat, P.; Zhang, C.; Zaviska, F. Recent advances in capacitive deionization: A comprehensive review on electrode materials. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suss, M.E.; Porada, S.; Sun, X.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Yoon, J.; Presser, V. Water Desalination via capacitive deionization: What is it and what can we expect from it? Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2296–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmatifar, A.; Palko, J.W.; Stadermann, M.; Santiago, J.G. Energy breakdown in capacitive deionization. Water Res. 2016, 104, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; He, D.; Zhang, C.; Kovalsky, P.; Waite, T.D. Comparison of faradaic reactions in Capacitive Deionization (CDI) and Membrane Capacitive Deionization (MCDI) water treatment processes. Water Res. 2017, 120, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Jo, K.; Kim, K.J.; Yoon, J. Effects of characteristics of cation exchange membrane on desalination performance of membrane capacitive deionization. Desalination 2019, 458, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.M.; Van Der Wal, A. Membrane capacitive deionization. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 346, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, J. Performance comparison and energy consumption analysis of capacitive deionization and membrane capacitive deionization processes. Desalination 2013, 324, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; An, J.; Yeon, S.; Oh, H.J. Evaluation of total dissolved solids removal characteristics by recycling concentrated water in membrane capacitive deionization process. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 264, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Lee, B.; An, J.; Yeon, S.; Je Oh, H. Performance optimization of a pilot-scale Membrane Capacitive Deionization (MCDI) system operating with circulation process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 343, 126937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Oh, C.; An, J.; Yeon, S.; Oh, H.J. Optimizing operational conditions of pilot-scale membrane capacitive deionization system. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-H.; Kao, Y.-H.; Shen, Y.-Y.; Fan, C.-S.; Hou, C.-H. Pilot-scale membrane capacitive deionization for water reclamation: Commissioning, performance benchmarking, and long-term assessment. Desalination 2025, 599, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Jeon, S.; Min, T.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, G. Pilot-scale capacitive deionization for water softening: Performance, energy consumption, and ion selectivity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, Z.S.; Alharbi, K.N.; Alharbi, Y.; Almoiqli, M.S. Innovative pilot plant capacitive deionization for desalination brackish water. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrand, J.; Dutta, J. Flexible modeling and control of capacitive-deionization processes through a linear state-space dynamic Langmuir model. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Oyarzun, D.I.; Hawks, S.A.; Stadermann, M.; Santiago, J.G. High water recovery and improved thermo dynamic efficiency for capacitive deionization using variable flowrate operation. Water Res. 2019, 155, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.P.; Lee, C.; Kim, C.; Yoon, J. Performance analysis of the multi-channel membrane capacitive de ionization with porous carbon electrode stacks. Desalination 2020, 479, 114315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Biesheuvel, P.; Miedema, H.; Bruning, H.; Van der Wal, A. Charge efficiency: A functional tool to probe the doublelayer structure inside of porous electrodes and application in the modeling of capacitive deionization. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanvand, A.; Chen, G.Q.; Webley, P.A.; Kentish, S.E. A Comparison of multicomponent electrosorption in capacitive de ionization and membrane capacitive deionization. Water Res. 2018, 131, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Omosebi, A.; Landon, J.; Liu, K. Enhanced salt removal in an inverted capacitive deionization cell using amine modified microporous carbon cathodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10920–10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorji, P.; Kim, D.I.; Hong, S.; Phuntsho, S.; Shon, H.K. Pilot-scale membrane capacitive deionisation for effective bromide removal and high water recovery in seawater desalination. Desalination 2020, 479, 114309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Liang, J.; Tang, W.; He, D.; Yan, M.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Tang, N.; Huang, M. Versatile applications of Capacitive Deionization (CDI)-based technologies. Desalination 2020, 482, 114390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; He, C.; Fletcher, J.; Waite, T.D. Energy recovery in pilot scale membrane CDI treatment of brackish waters. Water Res. 2020, 168, 115146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-C.; Lee, M.; Hou, C.-H. Development and environmental performance of a pilot-scale membrane capacitive deionization system for wastewater reclamation: Long-term operation and life cycle analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Process | Water Flow | Feed Water (mg/L) | Applied Voltage (V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCDI Process | Adsorption | ①→②→③ | 1000 (NaCl) | +283.2 |

| Desorption | ①→②→③ | 1000 (NaCl) | −283.2 | |

| C-MCDI Process | Adsorption | ①→②→③ | 1000 (NaCl) | +283.2 |

| Desorption | ④→①→②→⑤ | 120 (Tap water) | −283.2 |

| Type of Cycle | Operation Conditions (Adsorption/Desorption, min) |

|---|---|

| Symmetric conditions | 2/2, 3/3, 4/4 |

| Asymmetric conditions | 5/2, 5/3, 5/4 |

| Conditions | Removal Efficiency (%) | Energy Consumption (kWh/m3) | Feasible Cycle Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2/2 MCDI | 91.07 | 0.511 | 15 |

| 3/3 MCDI | 91.48 | 0.526 | 15 |

| 4/4 MCDI | 91.19 | 0.553 | 15 |

| 5/2 MCDI | 92.08 | 0.497 | 15 |

| 5/3 MCDI | 92.99 | 0.525 | 15 |

| 5/4 MCDI | 91.63 | 0.558 | 15 |

| 2/2 C-MCDI | 90.22 | 0.548 | 7 |

| 3/3 C-MCDI | 90.93 | 0.592 | 6 |

| 4/4 C-MCDI | 91.36 | 0.557 | 4 |

| 5/2 C-MCDI | 90.72 | 0.584 | 5 |

| 5/3 C-MCDI | 91.46 | 0.556 | 3 |

| 5/4 C-MCDI | 90.47 | 0.587 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, C.; Oh, H.J.; Yeon, S.; Lee, B.; An, J. Comparative Analysis of MCDI and Circulation-MCDI Performance Under Symmetric and Asymmetric Cycle Modes at Pilot Scale. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219744

Oh C, Oh HJ, Yeon S, Lee B, An J. Comparative Analysis of MCDI and Circulation-MCDI Performance Under Symmetric and Asymmetric Cycle Modes at Pilot Scale. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219744

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Changseog, Hyun Je Oh, Seungjae Yeon, Bokjin Lee, and Jusuk An. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of MCDI and Circulation-MCDI Performance Under Symmetric and Asymmetric Cycle Modes at Pilot Scale" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219744

APA StyleOh, C., Oh, H. J., Yeon, S., Lee, B., & An, J. (2025). Comparative Analysis of MCDI and Circulation-MCDI Performance Under Symmetric and Asymmetric Cycle Modes at Pilot Scale. Sustainability, 17(21), 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219744