Fostering Sustainability Integrity: How Social Trust Curbs Corporate Brownwashing in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data

3.2. Variables and Empirical Model

3.2.1. Measuring Brownwashing

3.2.2. Measuring Social Trust

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Empirical Model

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

4.3. Endogeneity Tests

4.3.1. Instrumental Variables Approach

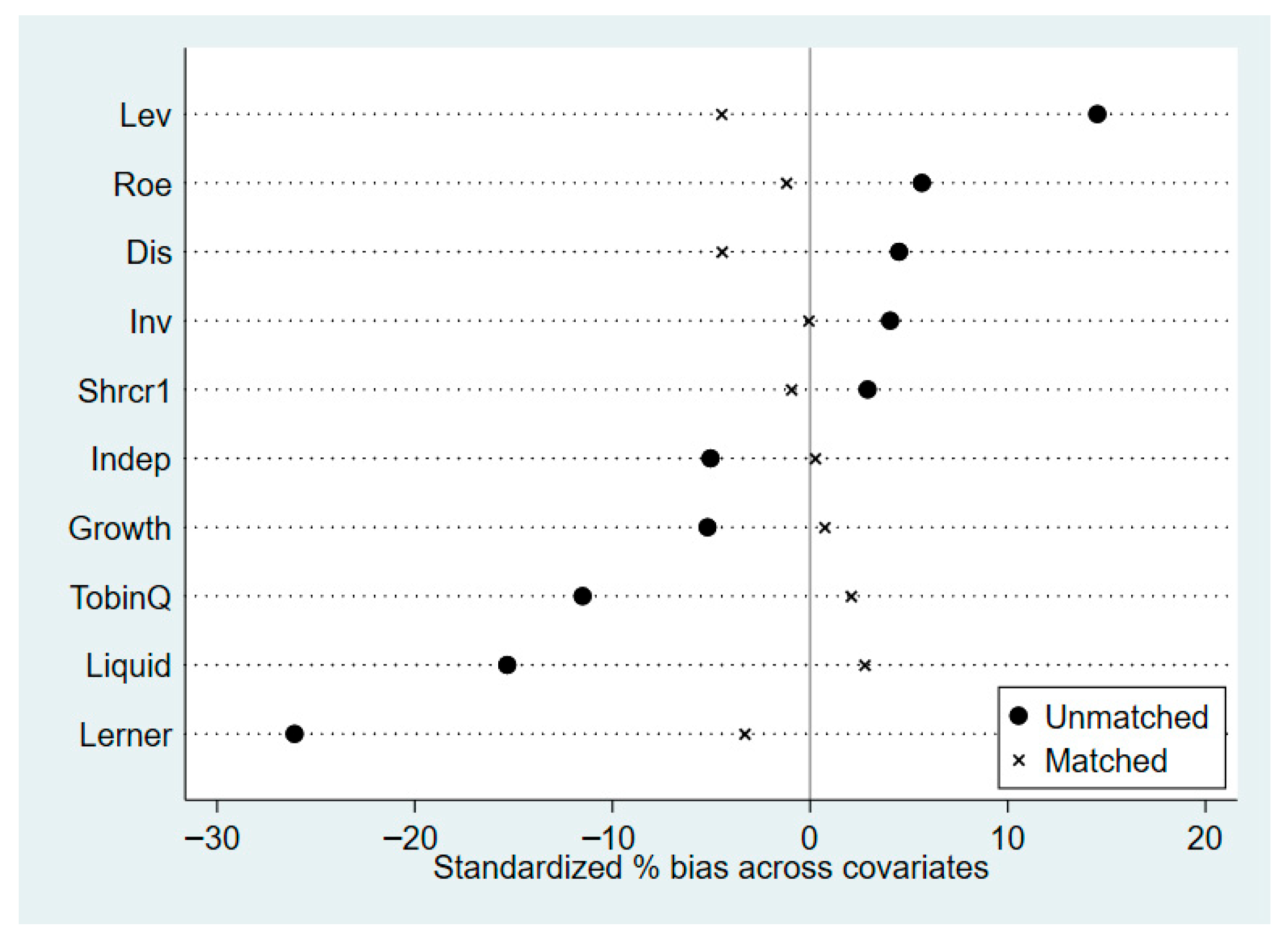

4.3.2. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

4.3.3. Difference-in-Difference Analysis

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Alternative Measure of Social Trust

4.4.2. Alternative Measure of Brownwashing

4.4.3. Alternative Fixed Effect

4.4.4. Adjusting the Sample Period

4.4.5. Alternative Estimation Models

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Mechanism Test: The Governance Channels of Social Trust

5.1.1. External Governance Channel

5.1.2. Internal Governance Channel

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.2.1. Ownership Structure

5.2.2. Legal Environment

5.2.3. Market Competition

5.2.4. Industry Pollution Level

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| BW | Trust | Lev | Roe | Inv | Dis | Lerner | Liquid | Growth | TobinQ | Indep | shrcr1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | 1 | |||||||||||

| Trust | −0.118 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Lev | −0.221 *** | 0.059 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Roe | 0.010 | 0.011 | −0.105 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Inv | −0.067 *** | 0.010 | 0.046 *** | 0.001 | 1 | |||||||

| Dis | −0.054 *** | 0.013 | −0.024 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.002 | 1 | ||||||

| Lerner | 0.032 *** | −0.091 *** | 0.105 *** | −0.113 *** | 0.097 *** | −0.041 *** | 1 | |||||

| Liquid | 0.221 *** | −0.087 *** | −0.663 *** | 0.047 *** | −0.104 *** | −0.004 | −0.042 *** | 1 | ||||

| Growth | 0.042 *** | −0.020 ** | 0.038 *** | 0.009 | −0.186 *** | −0.012 | −0.052 *** | 0.013 | 1 | |||

| TobinQ | 0.149 *** | −0.041 *** | −0.304 *** | 0.213 *** | −0.101 *** | 0.058 *** | −0.083 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.014 * | 1 | ||

| Indep | 0.022 *** | −0.047 *** | 0.006 | −0.001 | −0.017 ** | 0.012 | −0.014 * | 0.004 | 0.014 * | 0.039 *** | 1 | |

| shrcr1 | −0.020 ** | −0.002 | 0.061 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.051 *** | −0.021 *** | −0.017 ** | −0.089 *** | 0.056 *** | 1 |

Appendix A.2

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Escore | Negative Environmental News | |

| Real | 0.036 *** | −0.111 *** |

| (2.905) | (−2.790) | |

| Cons | 1.048 *** | 0.023 |

| (16.681) | (0.099) | |

| N | 14,838 | 12,456 |

| R2 | 0.069 | 0.613 |

| Ind | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

Appendix A.3

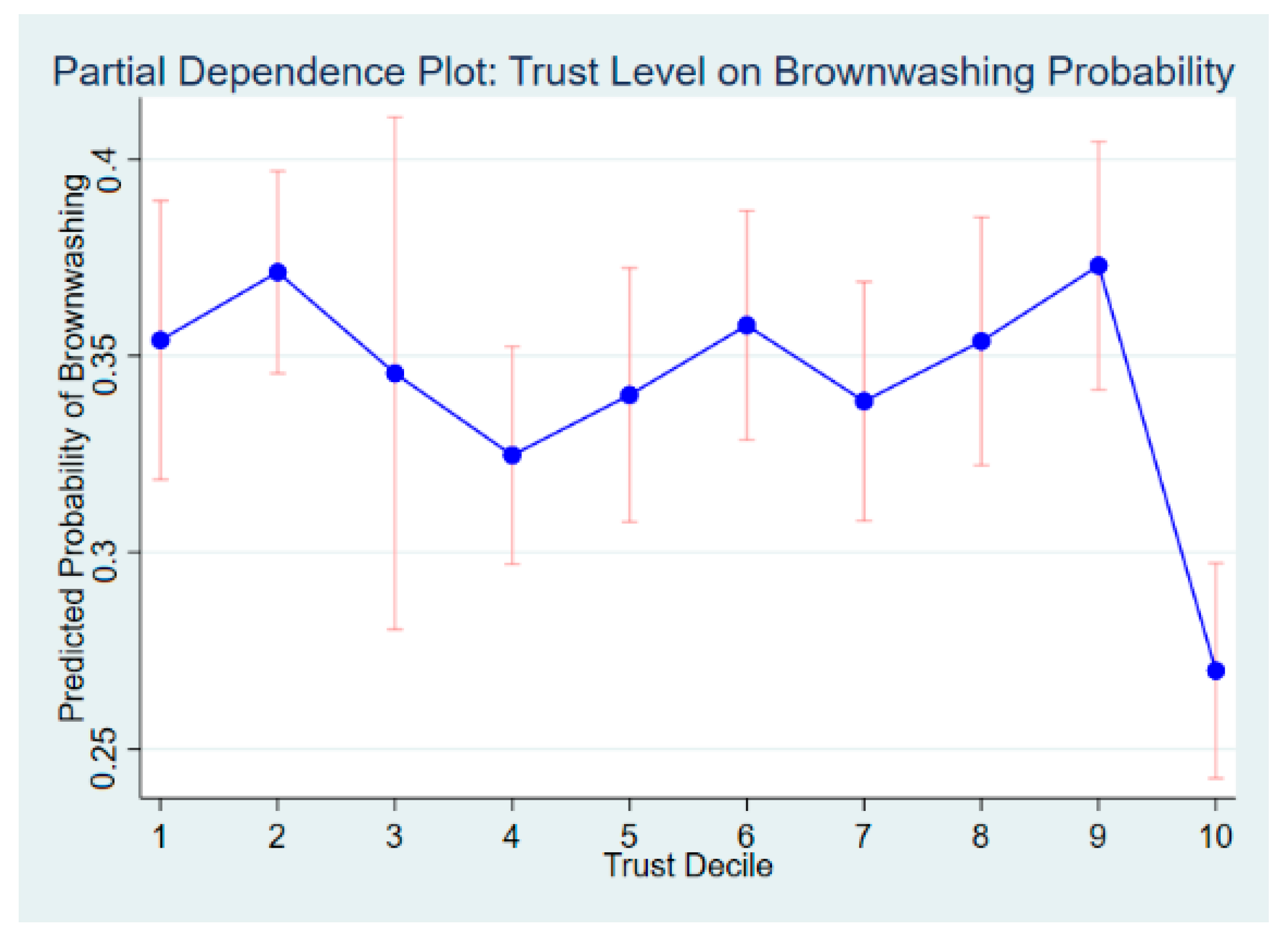

Appendix A.3.1. The Threshold Effect of Social Trust

| Trust Decile | Predicted Probability | Difference from Baseline | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.354 | ---- | Not Significant |

| 2 | 0.371 | +0.017 | Not Significant |

| 3 | 0.346 | −0.008 | Not Significant |

| 4 | 0.325 | −0.029 | Not Significant |

| 5 | 0.340 | −0.014 | Not Significant |

| 6 | 0.358 | +0.004 | Not Significant |

| 7 | 0.338 | −0.016 | Not Significant |

| 8 | 0.354 | 0.000 | Not Significant |

| 9 | 0.373 | +0.019 | Not Significant |

| 10 | 0.270 | −0.084 *** | p < 0.01 |

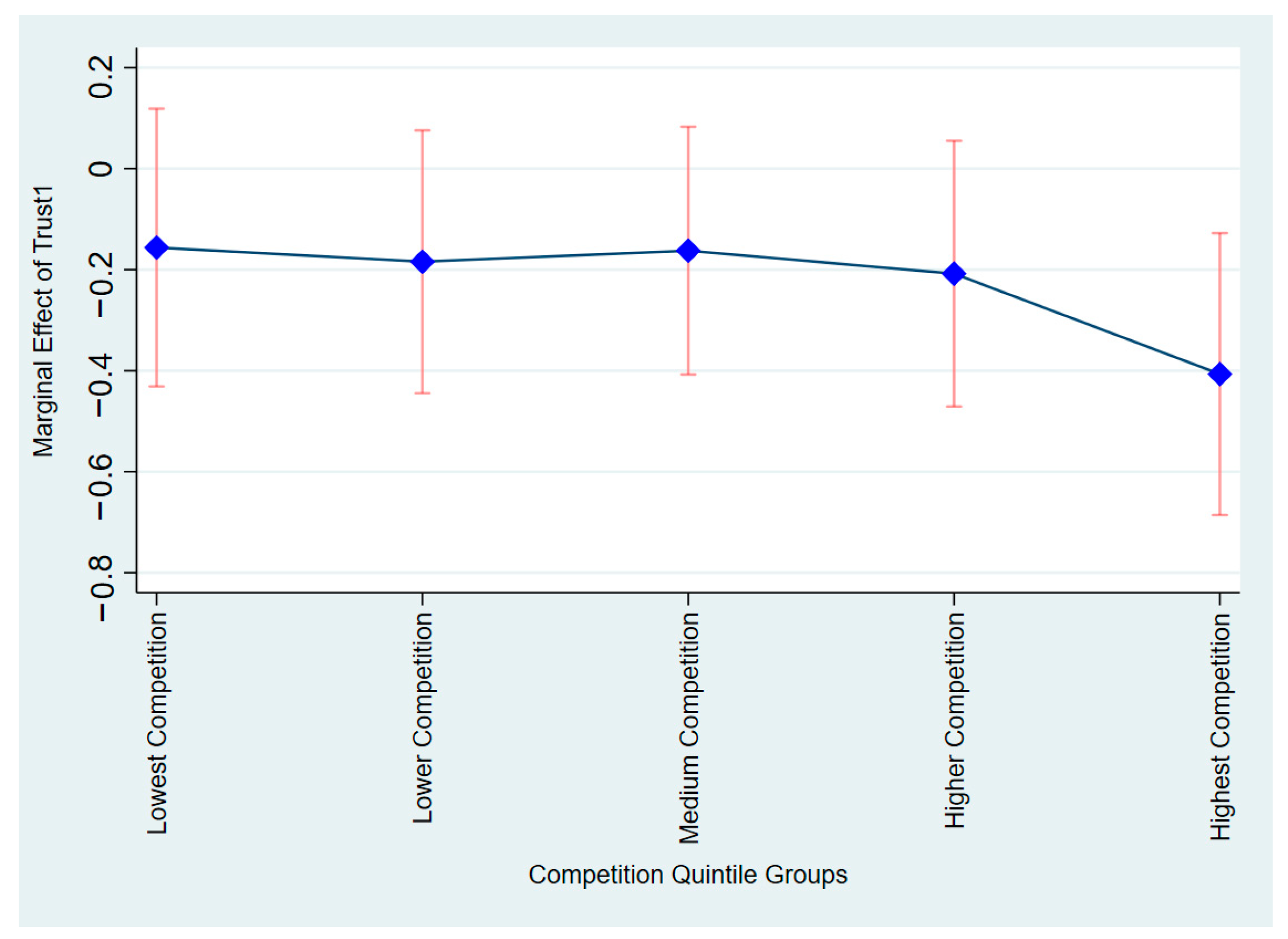

Appendix A.3.2. Market Competition as an Amplifier

| Competition Group | Marginal Effect | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest Competition | −0.1562 | 0.266 | [−0.431, 0.119] | Not Significant |

| Lower Competition | −0.1843 | 0.165 | [−0.445, 0.076] | Not Significant |

| Medium Competition | −0.1624 | 0.194 | [−0.408, 0.083] | Not Significant |

| Higher Competition | −0.2079 | 0.121 | [−0.471, 0.055] | Not Significant |

| Highest Competition | −0.4067 | 0.004 | [−0.686, −0.128] | p < 0.01 |

Appendix A.4

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| BW | |

| Trust | −0.245 ** |

| (−2.048) | |

| Polluting × post2018 × Trust | −0.515 ** |

| (−2.015) | |

| Cons | 0.518 *** |

| (6.278) | |

| N | 15,081 |

| R2 | 0.136 |

| Controls | YES |

| Ind | YES |

| Year | YES |

References

- Amin, M.H.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K.A. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Twitter: Signalling or Greenwashing? Evidence from the UK. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 1745–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Su, K.; Cai, W.; Bai, M. Is Transparency in Sustainability the Fruit of Business Trust: Evidence from Sustainability Disclosure? Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 30, 2407–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Xie, J. Top Management Team Connectedness and Greenwashing. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 30, 3725–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The Harm of Symbolic Actions and Green-Washing: Corporate Actions and Communications on Environmental Performance and Their Financial Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ding, R.; Zhang, Z. What Role Do Directors’ Networks Play in Corporate Brownwashing? Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Miroshnychenko, I.; Barontini, R.; Frey, M. Does It Pay to Be a Greenwasher or a Brownwasher? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores-Salvadó, J.; Martin-de Castro, G.; Albertini, E. Walking the Talk, but above All, Talking the Walk: Looking Green for Market Stakeholder Engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Duan, D.; Yang, S. Do Green-Minded Executives Matter? Evidence from ESG Brownwashing Behaviour. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Francoeur, C.; Brammer, S. What Drives and Curbs Brownwashing? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2518–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R.M.; Williamson, R. Culture, Openness, and Finance. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 70, 313–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ke, Y. “Fidelity” or “Exploitation”: Social Trust and Corporate Greenwashing. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 86, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, M. The Bright Side of Social Trust and Entrepreneurial Finance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, R.E. Essays on Disclosure. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 32, 97–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.A.; Mushtaq, R.; Orij, R. The Power of the CEO and Environmental Decoupling. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3951–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Bogner, W.C. Deciding on ISO 14001: Economics, Institutions, and Context. Long Range Plann. 2002, 35, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, A.; Lyon, T.P.; Martin, S. Salience Games: Private Politics When Public Attention Is Limited. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. Board Gender Diversity and ESG Decoupling: Does Religiosity Matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4046–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ma, W.; Yang, C.; Yang, R. Enterprise Characteristics and Incentive Effect of Environmental Regulation. Int. Rev. Financ. 2025, 25, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wan, P. Social Trust and Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Maak, T. Social Trust and Corporate Greenwashing: Insights from China’s Pilot Social Credit Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.; Gaio, C.; Costa, E. Committed vs Opportunistic Corporate and Social Responsibility Reporting. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, P.; Peng, B. Does Environmental Credit Affect Bank Loans? Evidence from Chinese a-Share Listed Firms. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 30, 1225–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ni, J.; Yang, C. Climate Transition Risk and Industry Returns: The Impact of Green Innovation and Carbon Market Uncertainty. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 214, 124056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Political Trust and Government Performance in the Time of COVID-19. World Dev. 2024, 176, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilary, G.; Huang, S. Trust and Contracting: Evidence from Church Sex Scandals. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Liang, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Lu, M.; Shan, Y. Social Trust and Dividend Payouts: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2022, 72, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.; Carter, M. Behavioral Responses to Natural Disasters; George Mason University, Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science: Arlington, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Liu, J.; Peng, Y. Locality Stereotype, CEO Trustworthiness and Stock Price Crash Risk: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 175, 773–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Algan, Y.; Cahuc, P.; Shleifer, A. Regulation and Distrust*. Q. J. Econ. 2010, 125, 1015–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotella, A.; Barclay, P. Failure to Replicate Moral Licensing and Moral Cleansing in an Online Experiment. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 161, 109967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Lee, M.-S.; Park, J.; Lee, H. Translating pro-environmental intention to behavior: The role of moral licensing effect. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; McDonald, B.; Yun, H. A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: The Use of Ethics-Related Terms in 10-K Reports. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hua, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. The Green Fog: Environmental Rating Disagreement and Corporate Greenwashing. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedhami, O.; Pan, Y.; Saadi, S.; Zhao, D. Do Environmental Penalties Matter to Corporate Innovation? Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, B. Does Social Trust Enhance Firm Engagement in Supply Chain Finance? Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 78, 107152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Firth, M.; Rui, O.M. Trust and the Provision of Trade Credit. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 39, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Tan, Y. Social Trust, Financial Constraints, and Enterprise Information Disclosure. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 83, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Chen, N. How Does Social Trust Promote Enterprises’ Financialization? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, D. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Kinship Networks and Entrepreneurs in China’s Transitional Economy. Researchgate 2004, 109, 1045–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, C. Trust, Investment, and Business Contracting. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2015, 50, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Trusting the Stock Market. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 2557–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wagner, E. Is Corporate Social Responsibility a Matter of Trust? A Cross-Country Investigation. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L. Environmental Regulations and the Greenwashing of Corporate ESG Reports. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 87, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, Y. Does Social Trust Affect Firms’ ESG Performance? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Han, H.; Ke, Y.; Chan, K.C. Social Trust and Corporate Misconduct: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, J. Do Green Investors Empower Companies to Develop Sustainably? A Study Based on the Perspective of Innovation Investment and Corporate Governance Levels. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 79, 107263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Jiang, N.; Su, W.; Dalia, S. How Does Customer Enterprise Digitalization Improve the Green Total Factor Productivity of State-Owned Suppliers: From the Supply Chain Perspective. Omega 2025, 133, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Tang, D.Y.; Zhong, R. The Effects of Mandatory ESG Disclosure Around the World. J. Account. Res. 2024, 62, 1795–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Leung, H.; Liu, L.; Qiu, B. Consumer Behaviour and Credit Supply: Evidence from an Australian FinTech Lender. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, C.; Chen, S. Why Is COD Pollution from Chinese Manufacturing Declining?—The Role of Environmental Regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Variable Name | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Brownwashing | BW | Dummy variable with a value of 1 if the firm engaged in brownwashing |

| Independent variables | Social Trust | Trust | Based on the provincial-level scores in the “China General Social Survey” |

| Control Variables | Leverage ratio | LEV | The proportion of total assets to total liabilities |

| Return on equity | Roe | Net Profit/Shareholders’ Equity Balance | |

| operating income growth rate | Growth | (Current Period Operating Profit—Prior Year Same Period Operating Profit)/Prior Year Same Period Operating Profit | |

| Tobin’s Q | TobinQ | Market Value/Total Assets | |

| current ratio | Liquid | Current Assets/Current Liabilities | |

| inventory turnover | Inv | Operating Costs/Ending Inventory Balance | |

| The inverse of the Lerner index | Lerner | The reciprocal of [(a single company’s operating income/total operating income within the industry) × cumulative Lerner index of individual stocks] | |

| Information disclosure | Dis | A is rated as excellent and assigned a value of four, and so on. | |

| The percentage of independent directors | Indep | Number of Independent Directors/Board Size | |

| The largest shareholder’s ownership percentage | Shrcr1 | the largest shareholder’s ownership percentage |

| Variable | Mean | Min | SD | p50 | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | 0.345 | 0 | 0.475 | 0 | 1 | 15,081 |

| Trust | 0.630 | 0.365 | 0.082 | 0.646 | 0.792 | 15,081 |

| Lev | 0.395 | 0.050 | 0.194 | 0.386 | 0.823 | 15,081 |

| Roe | 0.088 | −0.345 | 0.091 | 0.087 | 0.326 | 15,081 |

| Inv | 2.413 | −2.667 | 1.305 | 2.292 | 16.800 | 15,081 |

| Dis | 3.188 | 1 | 0.594 | 3 | 4 | 15,081 |

| Lerner | 11.260 | −39.84 | 7.963 | 9.166 | 130.100 | 15,081 |

| Liquid | 2.768 | 0.408 | 2.866 | 1.809 | 18.430 | 15,081 |

| Growth | 0.301 | −0.592 | 0.685 | 0.125 | 4.339 | 15,081 |

| TobinQ | 2.127 | 0.831 | 1.332 | 1.690 | 8.353 | 15,081 |

| Indep | 37.59 | 33.33 | 5.346 | 35.710 | 57.140 | 15,081 |

| Shrcr1 | 34.070 | 8.567 | 14.650 | 32.030 | 74.020 | 15,081 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| BW | BW | |

| Trust | −0.274 *** | −0.225 *** |

| (−3.071) | (−2.792) | |

| Lev | −0.324 *** | |

| (−7.854) | ||

| Roe | −0.034 | |

| (−0.621) | ||

| Inv | −0.007 | |

| (−1.196) | ||

| Dis | −0.043 *** | |

| (−5.207) | ||

| Lerner | −0.000 | |

| (−0.372) | ||

| Liquid | 0.016 *** | |

| (6.695) | ||

| Growth | 0.017 ** | |

| (2.005) | ||

| TobinQ | 0.039 *** | |

| (8.479) | ||

| Indep | 0.002 ** | |

| (2.072) | ||

| Shrcr1 | −0.000 | |

| (−0.311) | ||

| Cons | 0.518 *** | 0.563 *** |

| (9.078) | (7.313) | |

| N | 15,081 | 15,081 |

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.117 |

| Ind | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Stage | Second-Stage | First-Stage | Second-Stage | |

| Trust | BW | Trust | BW | |

| Clan culture | 0.329 *** | 0.243 *** | ||

| (12.424) | (7.886) | |||

| Dialect diversity | −0.053 *** | −0.051 *** | ||

| (−7.656) | (−7.707) | |||

| Trust | −0.923 *** | −1.455 *** | ||

| (−4.642) | (−5.494) | |||

| Cons | 0.583 *** | 0.947 *** | 1.078 *** | 1.544 *** |

| (48.887) | (6.497) | (17.010) | (3.377) | |

| N | 13,374 | 13,374 | 13,374 | 13,374 |

| R2 | 0.405 | 0.117 | 0.145 | 0.095 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Cragg-Donald Wald F | 205.295 *** | 112,856 *** | ||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM | 92.685 *** | 49.606 *** | ||

| Ind | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| BW | DID | |

| Trust | −0.197 ** | |

| (−2.102) | ||

| Treatpost | −0.069 *** | |

| (−3.677) | ||

| Cons | 0.564 *** | 0.420 *** |

| (6.183) | (5.079) | |

| N | 7971 | 14,531 |

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.521 |

| Ind | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing the Measurement Method | Alternative Fixed Effects | Adjusting the Sample Period | ||||

| BW | BW2 | BW3 | BW | BW | BW | |

| Trust | −0.223 ** | −0.431 *** | −0.201 ** | −0.227 *** | −0.267 *** | |

| (−2.277) | (−5.085) | (−2.315) | (−2.783) | (−2.869) | ||

| Trust2 | −0.122 *** | |||||

| (−2.951) | ||||||

| Cons | 0.478 *** | 0.620 *** | 2.984 *** | 0.578 *** | 0.560 *** | 0.548 *** |

| (7.940) | (6.640) | (8.161) | (3.167) | (7.220) | (6.104) | |

| N | 15,081 | 10,060 | 10,581 | 15,025 | 15,081 | 10,142 |

| R2 | 0.117 | 0.111 | 0.093 | 0.132 | 0.119 | 0.095 |

| text length | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Ind × Year | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPM | Probit | Logit | |

| BW | BW | BW | |

| Trust | −0.225 *** | −0.228 *** | −0.224 *** |

| (−2.792) | (−2.875) | (−2.842) | |

| N | 15,081 | 15,081 | 15,081 |

| R2 | 0.117 | 0.119 | 0.096 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Governance Channel | Internal Governance Channel | ||||

| Regulation | Pollution Control Expenditure | Governance | Executive Green Background | Board Size | |

| Trust | 0.001 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.858 *** | 0.172 * | 0.976 ** |

| (6.591) | (11.437) | (4.286) | (1.946) | (2.562) | |

| Cons | 0.002 *** | −0.002 * | −1.168 *** | 0.187 ** | 12.773 ** |

| (16.040) | (−1.864) | (−6.246) | (2.213) | (34.049) | |

| N | 13,598 | 15,081 | 14,400 | 14,504 | 15,081 |

| R2 | 0.130 | 0.369 | 0.506 | 0.099 | 0.316 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOEs | Non-SOEs | High Legal Environment | Low Legal Environment | |

| BW | BW | BW | BW | |

| Trust | −0.060 | −0.280 *** | −0.024 | −0.210 ** |

| (−0.463) | (−2.789) | (−0.142) | (−2.466) | |

| Cons | 0.383 *** | 0.560 *** | 0.474 *** | 0.499 *** |

| (2.950) | (5.857) | (3.573) | (5.373) | |

| N | 4263 | 10,817 | 7537 | 7543 |

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.117 | 0.122 | 0.127 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Competition Group | Low-Competition Group | Heavily Polluting Industries | Non-Heavily Polluting Industries | |

| BW | BW | BW | BW | |

| Trust | −0.296 *** | −0.144 | −0.260 *** | −0.190 |

| (−2.600) | (−1.409) | (−2.728) | (−1.285) | |

| Cons | 0.608 *** | 0.483 *** | 0.653 *** | 0.551 *** |

| (5.942) | (4.643) | (7.306) | (3.793) | |

| N | 7542 | 7539 | 10,306 | 4775 |

| R2 | 0.118 | 0.123 | 0.142 | 0.078 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zheng, S. Fostering Sustainability Integrity: How Social Trust Curbs Corporate Brownwashing in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219696

Wang L, Zheng S. Fostering Sustainability Integrity: How Social Trust Curbs Corporate Brownwashing in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219696

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, and Shijie Zheng. 2025. "Fostering Sustainability Integrity: How Social Trust Curbs Corporate Brownwashing in China" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219696

APA StyleWang, L., & Zheng, S. (2025). Fostering Sustainability Integrity: How Social Trust Curbs Corporate Brownwashing in China. Sustainability, 17(21), 9696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219696